The Grand Mozart Tradition Restored

Karl Böhm’s seminal way with Mozart’s final masterpiece receives the Original Source refresh

There’s a long history of certain pieces of classical music moving into the pop culture mainstream via their use in movies.

While extensive extracts from classical works were used to accompany silent movies, I’d argue that the first major example of this historically is the music used in Walt Disney’s Fantasia (1940). It wasn’t that these works were necessarily unknown before being used in the film (works like The Sorcerer’s Apprentice (Dukas), Beethoven’s Pastoral Symphony, and Tchaikovsky’s Nutcracker were all established favorites), it’s simply that after being used in the film they moved firmly into the cultural mainstream. Even a work like Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring - not on the general public’s radar before 1940 - gained an audience it would never otherwise have had. Dinosaurs will do that for a composer. Fantasia was also noteworthy for being the first film to attempt a more “audiophile” presentation of its music in theatres, with its Fantasound process pioneering surround sound.

Since then we’ve seen any number of classical works that were used in popular movies gain traction in the wider cultural marketplace as a result. Few knew Richard Strauss’s Also Sprach Zarathustra until its iconic opening fanfare was used extensively in 2001: A Space Odyssey. Wagner’s Ride of the Valkyries flew into the wider public consciousness when it was used to accompany (at length) the helicopter attack on a village in Apocalypse Now. Stanley Kubrick, ever the innovator in his use of music, gave a serious leg-up to Beethoven, Rossini, and even Purcell in A Clockwork Orange; Schubert in Barry Lyndon (the exquisite second movement of the Piano Trio No. 2 made repeated appearances, perfectly capturing the bitter-sweet mood of the hero’s rise and ignominious fall); Bartok and Penderecki in The Shining; even giving Ligeti’s piano études a platform in Eyes Wide Shut.

In Raging Bull Martin Scorsese foregrounded the heart-rending Intermezzo from Mascagni’s Cavalleria Rusticana; in Platoon, Samuel Barber’s Adagio for Strings was used to highlight the horrors of war; Beethoven’s 9th made another unexpected but memorable movie appearance in Die Hard; and everyone fell in love to the slow movement of Mozart’s Piano Concerto No. 21 in Elvira Madigan.

Unfinished portrait of Mozart by Joseph Lange (1789)

Unfinished portrait of Mozart by Joseph Lange (1789)

That same composer’s Requiem, left unfinished at the time of Mozart’s untimely death at the age of 35, found itself suddenly catapulted into pop culture with the success of the filmed version of Peter Schaffer’s zippy riff on Genius vs. Mediocrity, Amadeus (1984). A key sequence shows the dying Mozart dictating what will turn out to be his own Requiem to the predatory court composer Salieri, who has secretly engineered the younger man’s downfall to appease his own ferocious jealousy.

.jpg) Antonio Salieri

Antonio Salieri

It’s a compelling scene, and a complete fabrication, although it draws upon some elements of truth. The film shows Salieri secretly commissioning the work himself so he can pass it off as his own composition. In truth, the work was commissioned by Count Franz von Walsegg to commemorate the anniversary of his wife’s death, though he had a habit of passing off others’ music as his own. In this case he was prevented from doing the same with the Requiem by Mozart’s widow Constanze arranging an early public performance of the work to raise much needed family funds.

Constanze Mozart (Lange, 1783)

Constanze Mozart (Lange, 1783)

Constanze was also the source for a number of rumours concerning the mysterious identity of the Requiem's commissioner, and the fact that Mozart came to believe he was writing his own Requiem - all in the name of drumming up public interest in a good yarn to solicit financial donations.

Anyway, it all makes for a terrific scene in the film as we hear Mozart conjuring the music out of his fevered brain while Salieri dutifully transcribes, marveling at Mozart’s genius powers of invention.

In the end, Mozart did indeed die before completing the work, which was left to his former pupil Franz Süssmayr to finesse into a final performing edition. This is the version of the Requiem most commonly performed since, although various other completions have been made in recent decades, most notably (and radically) by Richard Maunder (his version is the one championed and recorded by Christopher Hogwood).

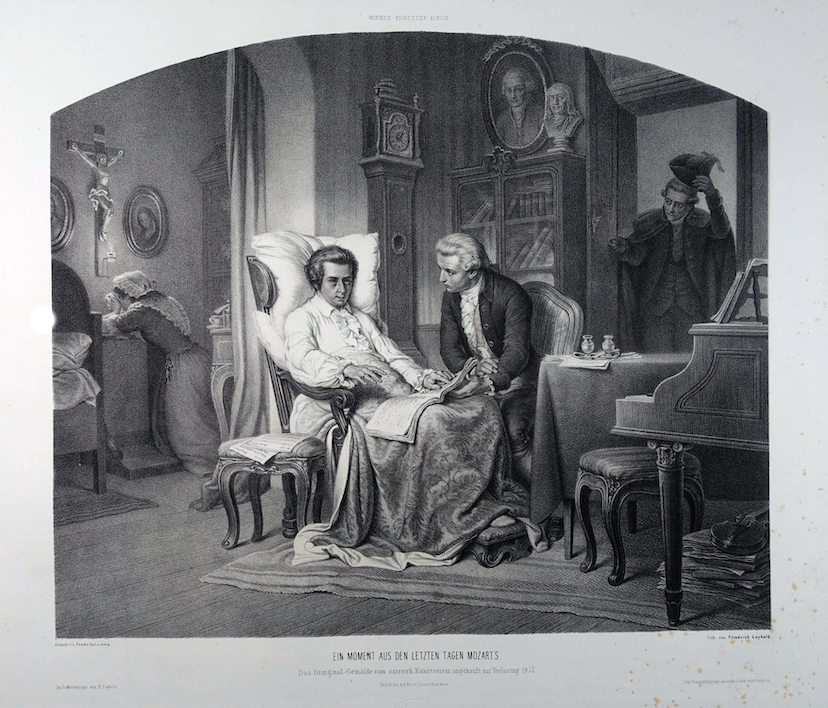

A mythical depiction of Mozart dictating the Requiem to Süssmayr

A mythical depiction of Mozart dictating the Requiem to Süssmayr

As a result of the film’s huge success, the Requiem suddenly became enormously popular, and recordings of it proliferated. The timing was propitious, since this was the dawn of the Historically Informed Performance era, which resulted in an explosion of new recordings of standard repertoire from the Baroque, Classical, and later on, the Romantic periods, all cast in the fresh sonorities of period instruments and performing styles of the new academic orthodoxy. Out went the “old ways” of doing big symphonies, choral works and operas in the “grand manner” with large orchestras and choirs, plus soloists with vibrato-laden “heavy”voices; in came the light textures, the speedy tempi, the smaller bands and chamber choirs and soloists whose voices were as light and fleet as air.

This was the ascendant age of the Hogwoods, the Gardiners, the Pinnocks and the Harnoncourts. The Karajans and the Klemperers, the Giulinis and the Böhms were suddenly very much out of fashion. And thus it remained for quite a while. Certainly the occasional recording of this repertoire from someone like Charles Mackerras or Neville Marriner emerged that was “period aware”, while not actually being played on period instruments, and it was indeed Marriner who was in charge of recording all the music for the soundtrack of Amadeus.

The recording of the Requiem under consideration here belongs firmly in the camp of the older generation, pre-HIP (Historically Informed Performance). But it would be a big mistake to dismiss recordings like this and others of its ilk merely because they do not conform to current notions of what is academically and historically “correct”. As we have entered what is essentially the sixth decade of HIP on record, it has been really refreshing to see something of a critical and popular re-engagement with this older performing tradition emerge, as preserved in older recordings. Great music can withstand all manner of different approaches.

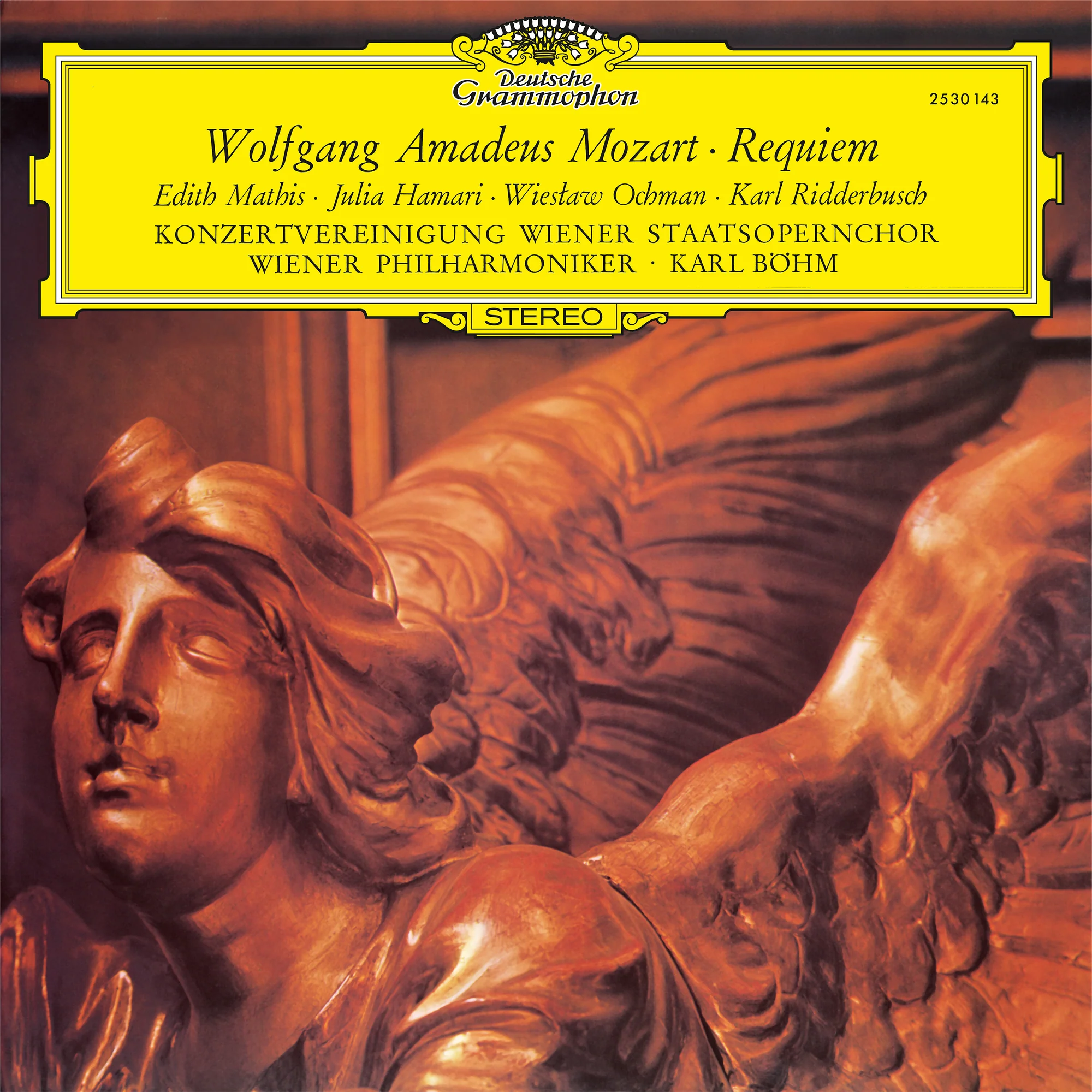

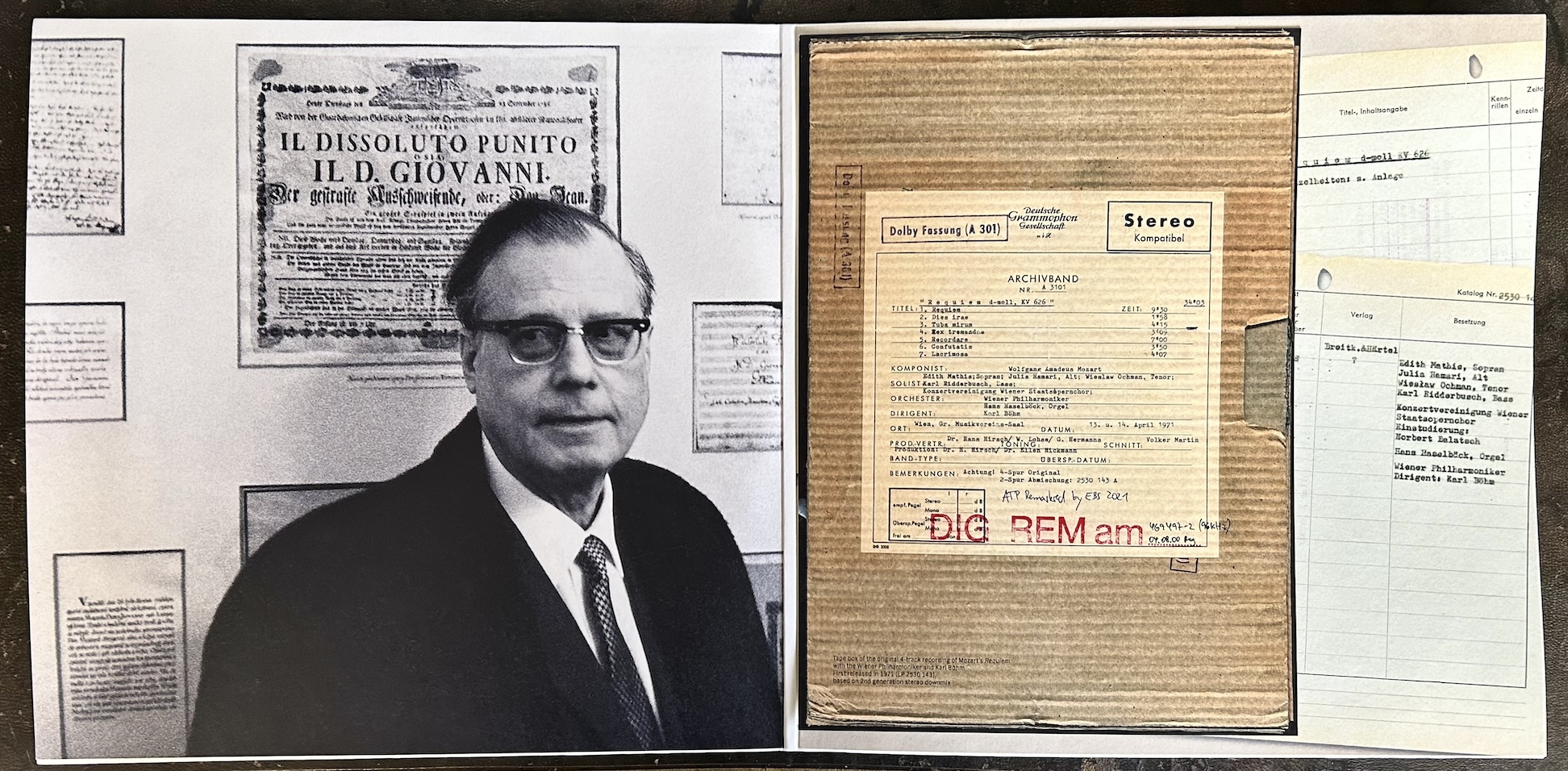

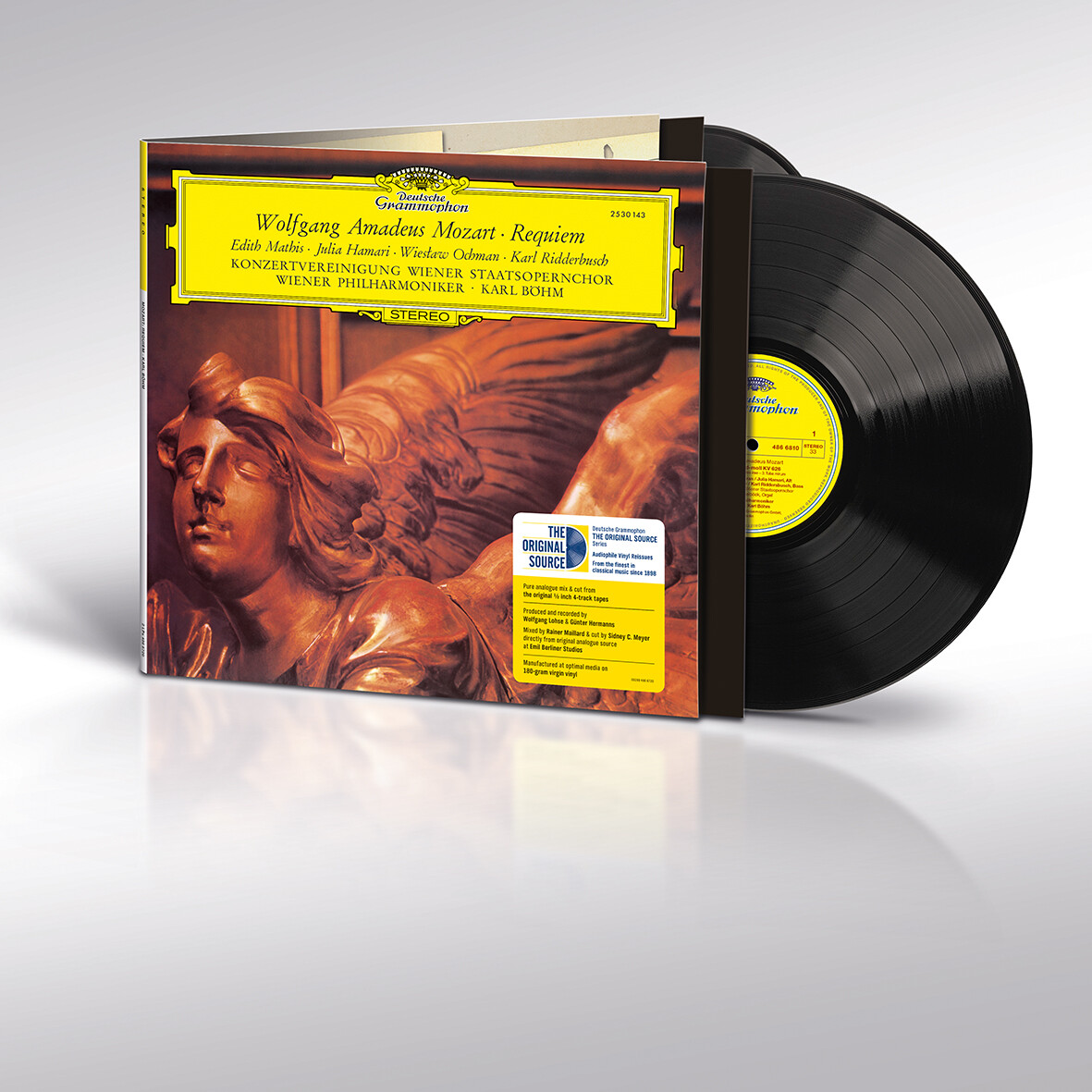

So with the usual stunning sonic refresh of this Original Source Remastering in hand, courtesy of the wizards at Emil Berliner Studio - Rainer Maillard and Sidney C. Meyer - this has proven to be the perfect opportunity to revisit and reassess a DG catalogue staple.

Karl Böhm

Karl Böhm

Throughout his life the Austrian conductor Karl Bohm was considered something of an echt Mozartian. His cycle (with the Berlin Philharmonic) of all the symphonies for DG - a monumental, pioneering undertaking - remains a central recommendation for a traditional approach in the catalogue (along with Josef Krips’s incomplete survey on Philips). Böhm's recordings of the operas are essential, especially his Le Nozze di Figaro (look for a large tulips pressing).

Böhm was as old school as it gets, a friend of - and proselytizer for - Richard Strauss, and less commendably more of a fellow traveler with the Nazi party than either Karajan or Furtwängler. His early training and experience was in the opera house, and he remained a supreme exponent of the operatic repertoire, above all Strauss, Wagner, Mozart and even Berg (his pioneering recordings of the operas Wozzeck and Lulu on DG remain top choices, and his Ring cycle recorded live at Bayreuth for Philips is often unfairly passed over in comparison to Karajan and Solti).

This recording of Mozart’s Requiem was unknown to me before writing this review, and in all honesty I will confess to the work being far from my list of favorites, even though I have sung it. (Like many I tend to prefer the Mass in C minor, which I sang at school). I also produced a live recording of the Requiem (in the Maunder completion) with Christopher Hogwood and the Handel and Haydn Society for NPR back in the day. Nevertheless, I was intensely curious to audition this Böhm rendering from 1971…

Böhm’s intentions are clear from the outset. The opening string footfalls and sustained, lamenting wind phrases of the Requiem Aeternam evoke a wintry funeral procession, slow and stately. When the choir enters with its plea (“Eternal rest grant them, O Lord, and let perpetual light shine upon them…”) it is somewhat more commanding than pleading. Before long we hear the first entry of one of the glories of this recording, the voice of soprano Edith Mathis, as she declares mankind’s vow of fealty to the Almighty even in death.

Edith Mathis in 1969

Edith Mathis in 1969

In this Original Source remastering, Mathis’s voice expands effortlessly to fill the acoustical space of the Musikverein, which in this recording takes on something of a cathedral quality owing, no doubt, to the large number of microphones needed to accommodate the large orchestra and choir. However the large acoustic never overwhelms the direct sound, and anoints a suitably ecclesiastical aura upon the proceedings. The more three-dimensional rendering typical of all these Original Source reissues is a result of folding in the surround channels, and there is a greater coherence and expanse to the soundstage than on the original LP.

Musikverein, Vienna

Musikverein, Vienna

The large Kyrie double fugue is again taken at a noticeably steady pace, no doubt to emphasize the seriousness of the musical procedure and statement - a standard approach pre-HIP. This is where a listener familiar with today’s speedier tempi in this kind of music might feel the performance is a bit heavy-going. A quick comparison to Hogwood’s total timing of 2:31 compared to Böhm's 3:15 tells all; and even other large-scale performances from Frühbeck de Burgos (EMI) and Gary Bertini (Phoenix) clock in around that faster 2:30.

In general what we already hear emerging from Böhm is an inclination to use weight as much as speed to delineate the more ferocious passages of the work. Let me emphasize, however, that this is not dead weight as one might encounter with certain interpretations of, say, late Klemperer - or even Karl Richter in some of his recordings (his ghastly, dead-on-arrival Messiah, for example). This is weight as in letting the full force of Mozart’s utterances be felt as well as heard, with plenty of clear articulation still going on in the orchestra. The Original Source remastering not only aids in expanding the sense of a large body of performers in front of the listener, but also in making that inner articulation audible and present. Another delicious bonus is that whenever the organ makes its presence felt, we really hear and feel it.

The Organ in the Musikverein

The Organ in the Musikverein

As with the earlier Original Source reissue of Karajan’s Verdi Requiem, where the remastering allows the original recording to shine in ways previously unheard is in the solo voices. The full force and range of the human voice is articulated effortlessly, and expands with no sense of dynamic constraint, filling the acoustical space with none of the effort we hear on most recordings of large-scale vocal music in oratorios and opera. After the heaven-storming Dies Irae (“That day of wrath, that dreadful day/Shall heaven and earth in ashes lay”), Mozart’s quirky setting of the Tuba Mirum (“The mighty trumpet's wondrous tone/Shall rend each tomb's sepulchral stone/And summon all before the Throne”) for solo trombone and bass has real impact, with Karl Ridderbusch’s authoritative bass ringing out in all its glory. That trombone’s sonority is also revealed with a timbral fidelity and range that approaches the real thing, and resonates tellingly in the Musikverein acoustic.

Karl Ridderbusch

Karl Ridderbusch

When the other soloists (alto, Julia Hamari, and tenor, Wieslaw Ochmann) join Ridderbusch and Mathis we are treated to a masterclass in this kind of grand oratorio singing, with the revitalized sonics allowing us to fully enjoy every nuance of these wonderful voices as they interweave effortlessly. This is one of the best line-ups of solo voices in the Requiem on record that I’ve heard. (And the success of this remastering really makes me want to encourage DG to select an opera for future Original Source treatment).

For me this is the moment at which this recording really gets into its groove, confirmed by the Choir of the Vienna State Opera's authoritative statements in the Rex Tremendae (“King of tremendous majesty”).

Over and over again you will hear Böhm’s mastery as an opera conductor come through in how he uses the orchestra to lead and caress, cajole and underline the choral and vocal lines. Listen to how beautifully he supports the soloists in the Recordare.

And thus we arrive at the brilliantly conceived movement featured in Amadeus, the Confutatis, in which Mozart juxtaposes the souls of the dead writhing in the flames of eternal damnation with voices of supplication to the heavens (“I kneel with submissive heart, my contrition is like ashes, help me in my final condition”). It’s a steadier tempo than in other renderings, but once more Böhm’s brilliant way with the orchestral accompaniment points up every little detail to create a strong emotional effect.

That heart-rending emotion carries over into the Lacrimosa. Again, the steady tempo may be slower than expected, but Böhm and his choir are able to sustain the line and the intensity. The wailing, disjointed chromatic string figures that accompany the choir’s lament (“That day of tears and mourning, when from the ashes shall arise, all humanity to be judged. Spare us by your mercy, Lord, gentle Lord Jesus, grant them eternal rest. Amen.”) feel like they are rending the heavens. However, we know that Mozart's original contributions to this movement end at bar 8, so much of this is Süssmayr's own completion from the composer's sketches (many of which are lost).

If you are not sold on Böhm’s approach by this point you never will be. I must confess that I approached this recording with a degree of skepticism, but with each listening I found more to admire. The Original Source remastering has - true to form - lifted a veil, and one is able to listen into the performance, in particular to enjoy the solo voices in all their sonic glory, feel the weight and power of the choir, and discern all the filigree orchestral detail which Böhm brings out so effectively.

But... this remains a resolutely old-fashioned, maybe even stentorian performance. I can imagine that many will prefer something slightly less overtly “serious” or heavy in its manner. But this is a "Requiem" after all, so there is much to be gained from Böhm’s approach - and like I said before, this team of soloists is exquisite.

This is very much a record that is a matter of taste in terms of performance, but in matters of sound it yields to few other large-scale Requiem recordings that I’ve heard. Yes, the large choir occasionally sounds like it is pushing at the boundaries of what the tape can accommodate, but Rainer Maillard’s purist remastering and Sidney C. Meyer’s dynamic cutting obviate the shortcomings here as much as is possible. My only other quibble would be an occasional thinness in the violin sound, a characteristic of many DG recordings of this period. It’s tempered by the new remastering, but it's still there. Was this perhaps down to the microphones the DG engineers favored on certain recordings?

Pressed as always at Optimal at 33rpm, and smartly spread over four sides to prevent any chance of inner groove distortion, my copy was immaculate. The usual Original Source gatefold and insert give us full recording session information, original sleeve notes and extra photographs.

If you love this work, you are probably familiar with this recording already, and the sonic refresh is self-recommending. If you are more of a Mozart Requiem novice then I hope I have given you a good idea of whether this particular version is for you or not. Authenticists will want to investigate Hogwood’s fine version of Richard Maunder’s completion, and it’s a really good performance with excellent soloists and boys' voices (the Westminster Cathedral Choir). Hogwood doesn’t always get the credit I think he’s due in his choral and operatic re-thinks. For smaller forces you can go with John Butt, immaculately recorded as always on Linn. For a bigger-boned approach similar to Böhm, but with an inclination to move things along ever so slightly more, consider Rafael Frühbeck de Burgos and Gary Bertini (a new discovery for me).

A quick ratings note: I found this one hard to rate because a lot will depend on whether you respond to the performance or not - a performance which, in and of itself, is excellent. Also, while the sound is likewise excellent there are aspects to it which might bother some more than others. On the other hand the sonic refresh is substantial. In both cases I decided to err on the generous side. (I urge all to judge more by my comments than by my ratings).

This record preserves a long and noble tradition of fine Mozartian performance, and should not be dismissed simply because it does not fit in to current vogues of performance practice. There is a cumulative power and poignancy to this thoughtful account, the product of Böhm’s lifetime of contemplation and performance of this score, and this Original Source revitalization brings that wisdom vividly to life in your listening-room.

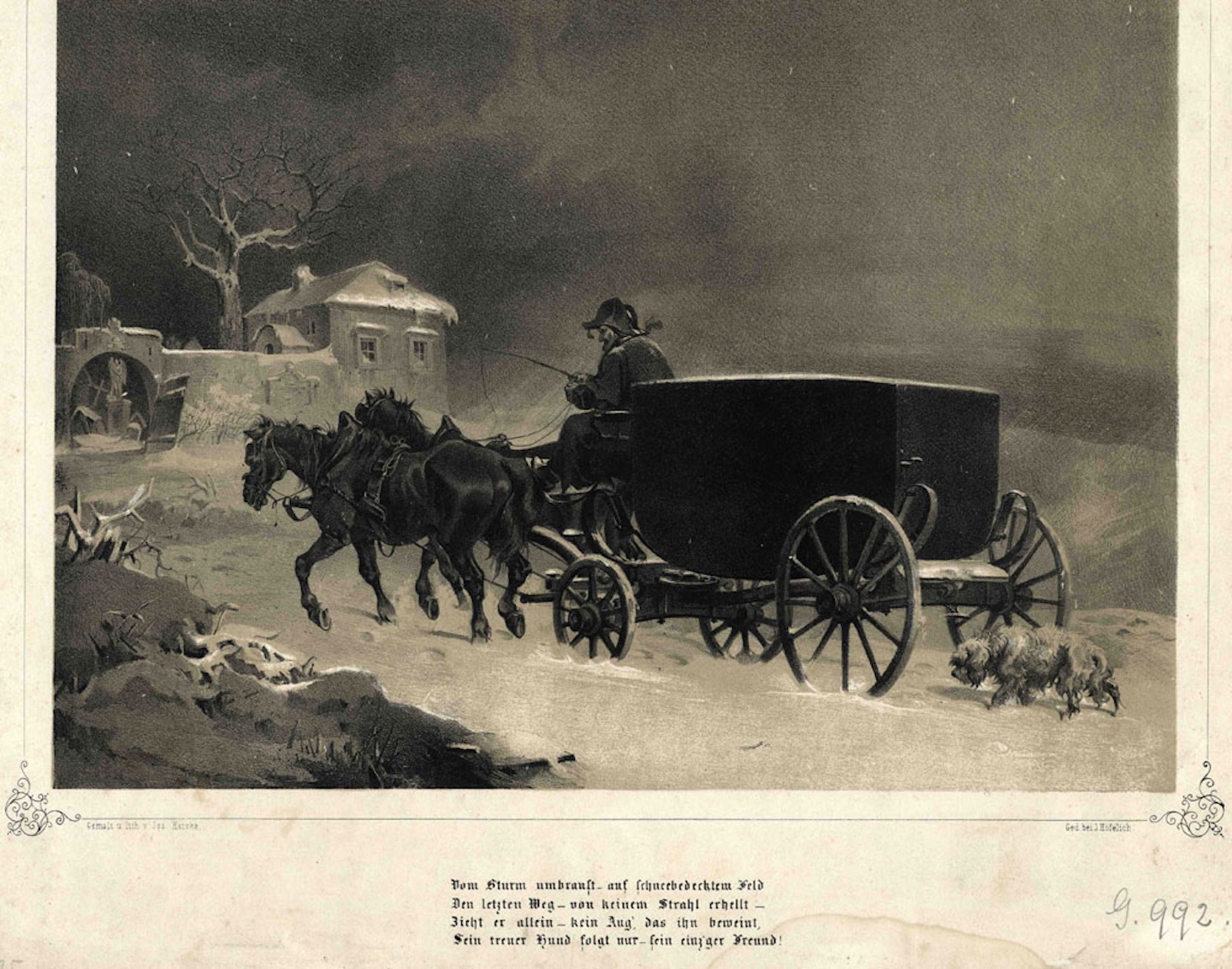

Joseph Heicke's engraving (c.1860) of the journey of Mozart's coffin through a storm to the cemetery: a somewhat romanticized and fictionalized version of the composer's funeral that quickly became mythologized in early accounts and biographies

Joseph Heicke's engraving (c.1860) of the journey of Mozart's coffin through a storm to the cemetery: a somewhat romanticized and fictionalized version of the composer's funeral that quickly became mythologized in early accounts and biographies

.png)