The Great Artistry of Django Reinhardt

Sam Records reissues electric Django in Artisan Series

The years after the liberation of France from German occupation in August 1944 were not easy ones for the great guitarist Django Reinhardt. Somehow, during the occupation, he had managed to remain in France and continue to play professionally with great success and even record while hundreds of thousands of fellow members of the Romany ethnic group were murdered by the Nazis.

After the war, he and violinist Stephane Grapelli, on several occasions, the last in 1948, had reunited The Quintette Of The Hot Club Of France (QHCF), the group that had made Reinhardt internationally famous and brought him acclaim as the first non-American jazz great, but the men had drifted apart. Reinhardt continued using the QHCF name for a group with a different instrumental configuration and a clarinet or sax as the other main soloist, but the magic of the original quintet was missing.

In 1946, Reinhardt toured extensively in the U.S. with the Duke Ellington Orchestra. Sadly, Ellington did not write any special compositions or arrangements to feature Reinhardt, who only did a short solo set. His behavior was erratic and unpredictable, missing gigs and showing up late, including the last stop on the tour at Carnegie Hall where he appeared at 11 pm as the Ellington band was concluding the concert. Audiences, many of whom had heard the pre-war QHCF records, came expecting that sound and were disappointed to hear Django playing electric guitar. Critical response was mixed. The existing recording of Django from the tour shows him struggling with the unfamiliar electric guitar, and is unimpressive.

When the Ellington tour concluded, Reinhardt played at New York’s Café Society Uptown for approximately a month. Then, a promised West Coast tour and any other gigs, failing to materialize, he returned to France in February 1947, deeply disappointed that the tour had not brought him the acclaim in America that he had expected.

Reinhardt’s popularity in France was waning and critics complained that “the old flame, the old urge to create seems to have left him.” Jazz was changing. In the U.S., Dizzy Gillespie and Charlie Parker had already made some of the seminal bebop recordings and revolutionized jazz. The Swing Era, acoustic string band style of Django and the QHCF was outdated. He was no longer at the forefront of jazz as he had been in the mid to late 30s when he had played with and was accepted as a peer of Coleman Hawkins, Benny Carter and other expatriate American greats.

Django took up painting and seemed more interested in it than music. In 1949, after tours of the U.K. and Italy, he couldn’t find any gigs in France and went into retirement and lived the Romany travelling life. He returned to playing and another tour of Italy in late 1949, but when it finished and he was back in Paris, he stopped playing again.

Little was heard of Reinhardt until February 1951, when he made a comeback, playing electric guitar with much younger, bop influenced players. Andre Ekyan, who had played in a later edition of the QHCF, said of Django’s return:

I believe his last few years were bitter ones. Whenever I met him he always seemed to be worried about something or other. There’s no doubt about it, with those new ideas jazz had taken a step forward. And there was the rub. For twenty years, Django had towered head and shoulders above his contemporaries. And then, after a few years away from the scene, it was suddenly brought home to him how much everything had altered. Not only were the musicians themselves different, their outlook and above all their musical conception had changed out of all recognition.

Django was in an artistic crisis. If he was going to remain a creative force in jazz, he had to find a way to incorporate the new harmonic and rhythmic ideas of bop into his music. The alternative was to hire a violinist to imitate Grapelli and endlessly recreate the QHCF.

He was not interested in profitable nostalgia, so Django, who in the mid-thirties had become the foremost and most influential virtuoso jazz guitar soloist, now, at forty-one years old, began the attempt to create a new, bop influenced style, while retaining the Romany passion and melodic and rhythmic influences that had always been such an important part of his music. It would not be easy. Django said:

…they give me a bad time now and again, those little kids who think it’s all happening, that we’re no good anymore, that we’re finished! But one day I got angry; I began to play so fast they couldn’t follow me! And I gave them some new numbers to play, with difficult sequences. And there again they were all at sea! They’ve got some respect for me now!

For the rest of his career, Reinhardt recorded and worked with modern jazz styled groups accompanying his acoustic Selmer guitar, electrified with a pickup, playing a mixture of 30s and 40s standards and his own bop flavored originals. Django’s sophisticated harmonic sense allowed him to adapt well to the bop idiom, but more surprising was his rhythmic sureness at fleet bop tempos. He was a very different musician than the one he had been before the war, but he was still Django.

On March 1, 1953, Reinhardt sat in with Dizzy Gillespie’s quintet at a Paris concert. A review stated, “Django was in brilliant form and delighted everybody, including Dizzy, who seems to have great regard for him…‘Swonderful’ featured a guitar-trumpet chase that showed these two musicians to be of the same exceptional class.” Django had great admiration for Gillespie, and to be accorded the honor of being asked to sit in with one of the creators of bop must have made him confident that he was on the path back to the forefront of jazz.

Two days later, Reinhardt met Norman Granz, owner of Clef Records and promoter of the phenomenally successful Jazz at the Philharmonic, backstage at a concert. They reached an agreement to feature Django on a JATP tour of the U.S., Europe, and Japan that fall, with an album to be recorded to serve as a promotional tool for Django’s appearance and a needed boost to his career.

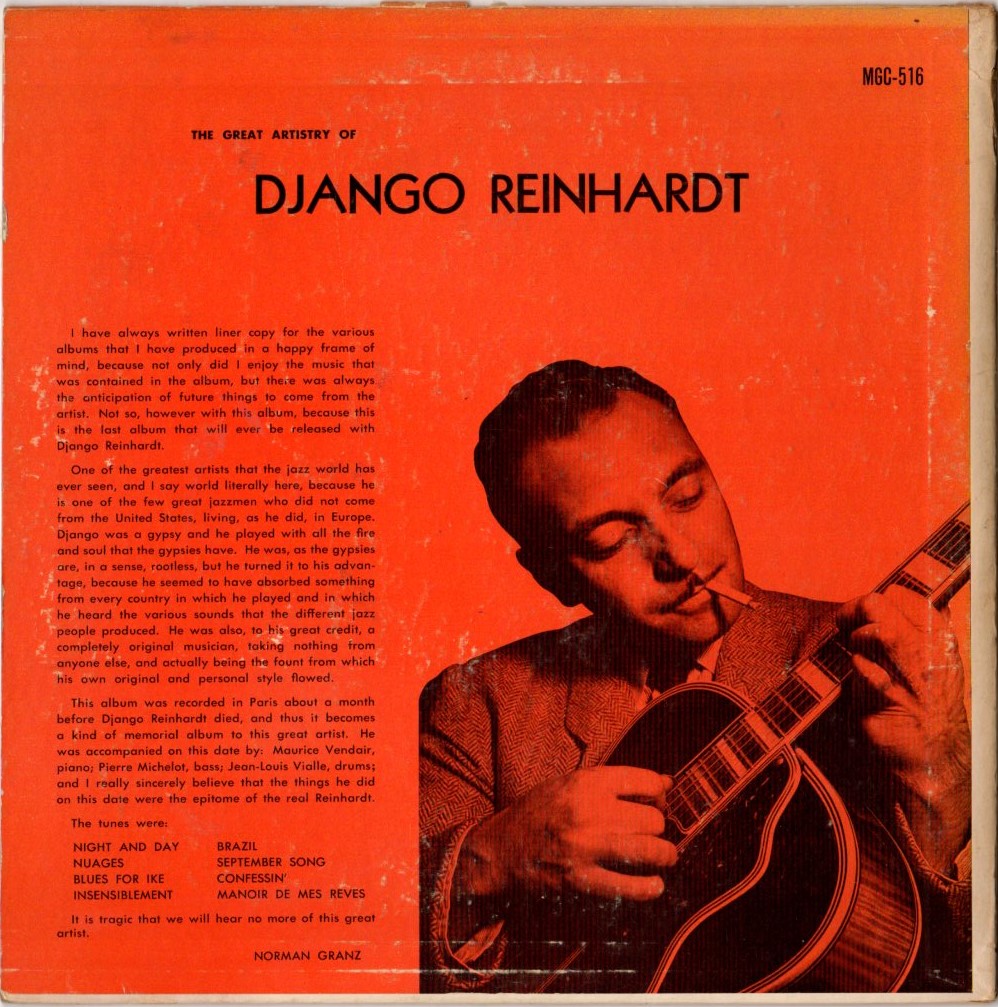

On March 10, 1953, Django Reinhardt, recorded eight tracks in Paris for the album, which would be entitled The Great Artistry of Django Reinhardt and released by Blue Star in France and Clef in the U.S. He was accompanied by the young bop styled rhythm section of Maurice Vander (1929-2017) piano, Pierre Michelot (1928-2005) bass and Jean-Louise Viale (1933-1984) drums; all of whom were infants or young boys when the QHCF made their first records. It was the only time in his career that Django recorded with only a piano, bass, drums trio.

The album begins with Cole Porter’s “Night And Day,” taken at a fast-medium tempo, and Reinhardt’s playing of the melody on his electrified Semer proves immediately that he is a masterful electric guitarist. His picking is hard and clean from all those years of playing acoustic, so beautifully articulated and phrased that one marvels at the beauty, not only of the melody but also of the individual notes. The guitar tone is not electric or metallic but smooth and sings with the woody mellowness of a clarinet. His solo is a masterpiece, continually referring to the melody while improvising chromatically on the chords. The backing trio provides a looser, lighter, more modern rhythm feel than the heavier, two additional guitars and bass of the QHCF, and Django’s lines float over them like Charlie Christian’s did in the Benny Goodman Quartet. At one point, he uses one of the favorite licks of Oscar Moore, guitarist for the Nat King Cole Trio. Clearly, Django had been listening to guitar developments in the U.S.

“Blues For Ike,” a 12 bar Reinhardt original, features some stunning runs, and at one point for a few bars, he falls into a very lowdown funky groove. His horn like lines and unique, sparse, two finger chording (his left hand had been badly burned in a fire and the ring and pinky fingers were partially paralyzed) probably influenced the style of 60s guitar great, Grant Green. Pierre Michelot, a very talented bass player who went on to record with Miles Davis on Elevator To The Gallows and extensively with Bud Powell, plays a melodic and adventurous solo that shows that he had heard Ray Brown.

“Nuages” is Django’s most famous composition which he recorded many times. As always, Django, who, like all the greatest jazz musicians, was a master of playing the melody, plays the theme with melancholy grandeur, making wonderfully subtle use of the sustaining capability of the electric guitar. This version features superb piano accompaniment by Maurice Vander, who manages, during the guitar solo, to play some interesting chords and add some nice fills behind Django’s astonishing scalar runs without getting in the way.

“Insensibilement” is a French pop song that seems ill suited to a jazz treatment, and the non-swinging, on the verge of dragging rhythm, makes for a dull performance. Django plays some fantastic, long lines and even some Charlie Parker style sudden bursts of abstract melody, but it seems like he’s trying too hard.

“Brazil” features the rhythm section playing a superb jazz/samba feel with the drums and bass locked in and grooving while Django plays the melody with his unique romantic melancholy before swinging hard in his solo. He plays long lines that, unlike those of many of the bop musicians, who played solely on the chord changes, never lose the melody and the melancholy.

“September Song,” usually performed as a slow ballad is played here at a subtly swinging mid-tempo. Django plays the melody with appropriate wistful sadness, avoiding the dramatic sentimentality that singers sometimes invest the song with. His solo starts with a Charlie Parker lick of outrageous dexterity and then it’s impossibly long and technically amazing bop lines through the harmonies while the piano plays sensitive fills.

Reinhardt had recorded “Confessin’,” a sentimental ballad from 1930, at the QHCF’s second recording session in 1935. This version seems to be performed with the intent of showing how much Django’s music had changed since then. He plays the melody loosely, interspersing some bop runs, and then plays his longest solo of the album, a three chorus masterpiece that moves far away from ballad feel, very freely running through the chords, almost ignoring them but staying in the key while improvising with amazing creativity and intensity on short rhythmic motives. This is very advanced playing for 1953 and presages the post-bop music Sonny Rollins would be playing in 1957.

Reinhardt plays the gorgeous melody of “Manoir Des Mes Reves,” aka “Mansion Of My Dreams,” aka “Django’s Castle,” with remembrance of lost time, heartbreak poignancy. His solo stays close to the melody. The great musicians know that sometimes that is enough.

The music on The Great Artistry of Django Reinhardt, clearly shows that Django was not a spent force. No other jazz guitarist in 1953 was playing bop at this level of harmonic sophistication, technique and hard swing with such melodic beauty and cool jazz lyricism.

In retrospect, it’s obvious that Granz and the JATP tour were going to make Django an international star again, but even more famous than he had been with the QHCF. His playing in jam sessions with Oscar Peterson, Roy Eldridge, and Ben Webster would be hard swinging and dazzling. The quartet set with him and Oscar Peterson tearing up “Fine and Dandy” before trading fours would end nightly with roaring standing ovations. The album he would record with Lester Young would be acclaimed a masterpiece meeting of kindred spirits. Then, there would be the recordings with Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie, the strings album with Nelson Riddle arrangements and, of course, Duke Meets Django: The Romany Suite. Like so many beautiful dreams, it was not to be.

Django died slightly over two months after recording The Great Artistry of Django Reinhardt, on May 16, 1953, due to a stroke.

The Great Artistry was recorded in what was apparently a small studio. There is not a lot of room sound or “air.” The piano, bass, and drums sound like they were set up close together, beneath an overhead mic with Django and his amplifier separately miked about fifteen feet in front. It’s definitely a Django-centric recording. Treble and bass are not fully extended. The cymbals do not ring with overtones. The bass is not bottom octave deep or realistically dynamic. Django’s guitar and the sweetness and bite of his sound is nicely recorded. This is probably the best recording of him playing electric. The recording is warm, smooth, and mellow. It’s a very good recording for 1953 but lacks the dynamic and tonal range of recordings made in the later 1950s.

I compared the Sam Records pressing to my original ten inch Clef pressing. The Sam LP was far superior sonically in every aspect and clearly had been mastered and the lacquer cut to compensate for the shortcomings of the original recording. The frequency extremes were more extended, there was some room sound and more space between the instruments.

Sam Records of Paris has reissued the ten inch, 33 rpm, Great Artistry of Django Reinhart on a 12 inch, 180 gram LP at 45 rpm in their Artisan series in a hand numbered edition of 500 copies. The Sam website states, “Mastered from the original mono tapes by Francois Le Xuan. Lacquers cut by Kevin Gray, Cohearent Audio. Pressed in Marciac, France by Garcia & Co.” I think we can assume Kevin Gray cut from files. The sound was warm, velvety smooth mono. My LP was lustrous, deep black, and flawless. It played superbly and near dead quiet. The LP was a state of the art in 2024 record pressing.

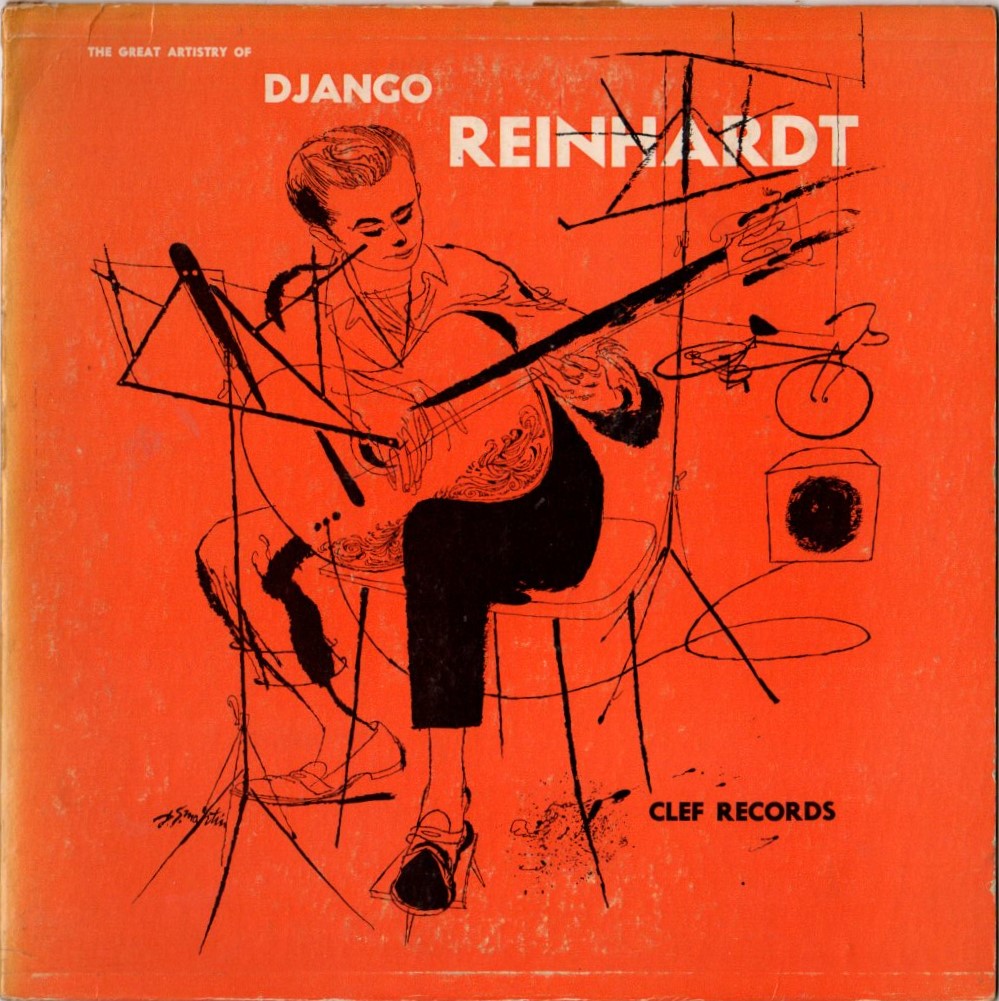

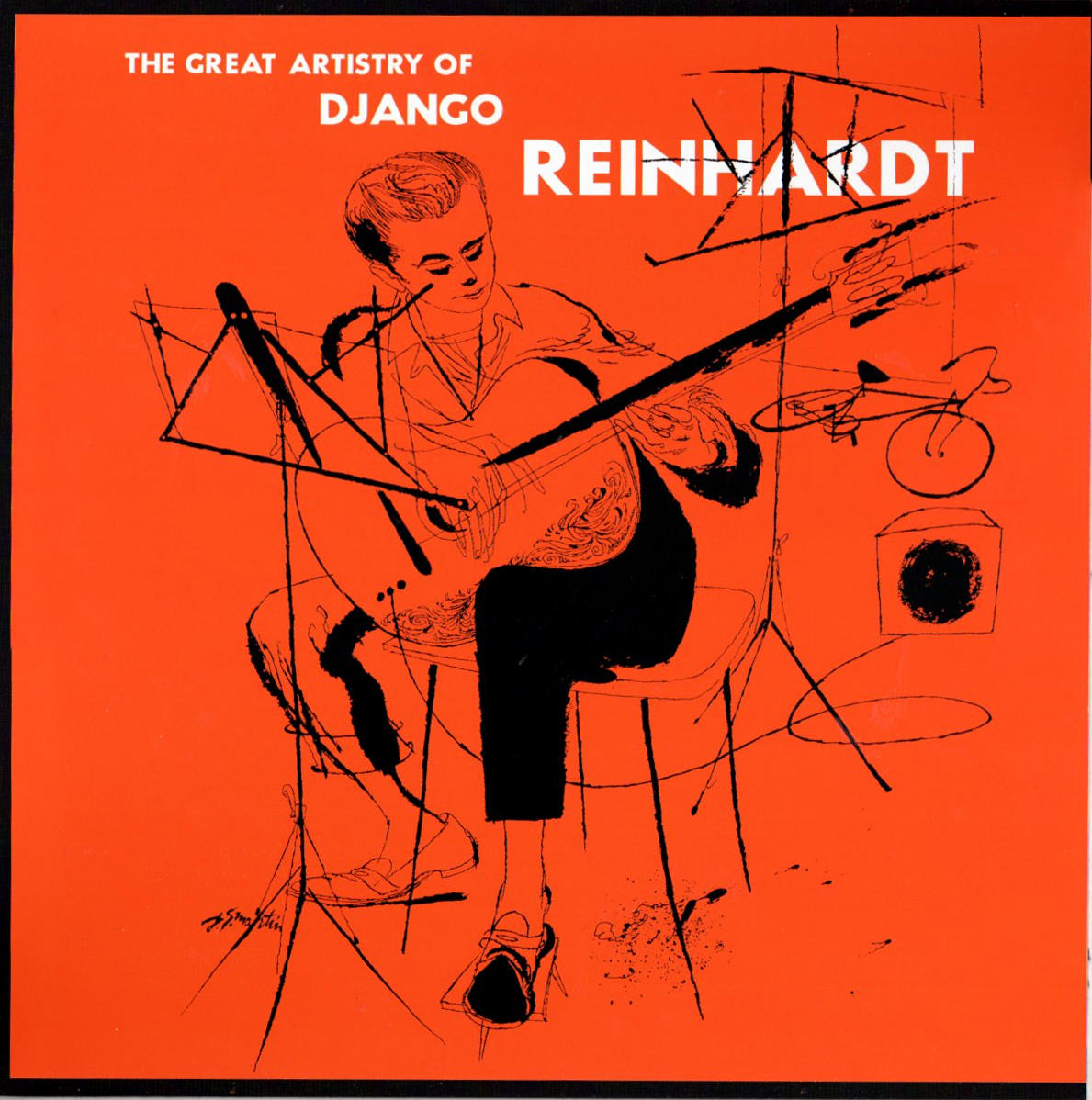

The Sam Artisan series is a “record series created by Sam Records and Saga designed for all jazz music and record cover art lovers.” David Stone Martin did the original artwork for The Great Artistry. Some have criticized Martin’s work as lacking in technical ability, and it must be admitted that the guitarist on the cover bears little, if any, resemblance to Django, but it is an evocative drawing. Sam has manually screen-printed the cover on heavy cardboard stock. The back cover is unprinted and black. Included with each LP is a six page 11 ½” x 11 ½” insert that includes two photos of Reinhardt and excellent notes by Alain Tercinet as well as Granz’ original notes.

The LP is available only on the Sam Records website and sells for 110 euros (app. $116), a price that seems reasonable for some great music superbly reproduced on a flawlessly pressed LP, encased in a cover that is a beautiful handmade art object. Recommended to those whose budget will allow purchase.

NOTE: I rated the sound "10" because this is the best these recordings will probably ever sound. But the original recordings were made in 1953 and are not high fidelity recordings. I think my review makes clear the limitations of the recordings and source material.

Copyright and all rights reserved by Joseph W Washek 2024.

.png)