The Original Source Goes Blue

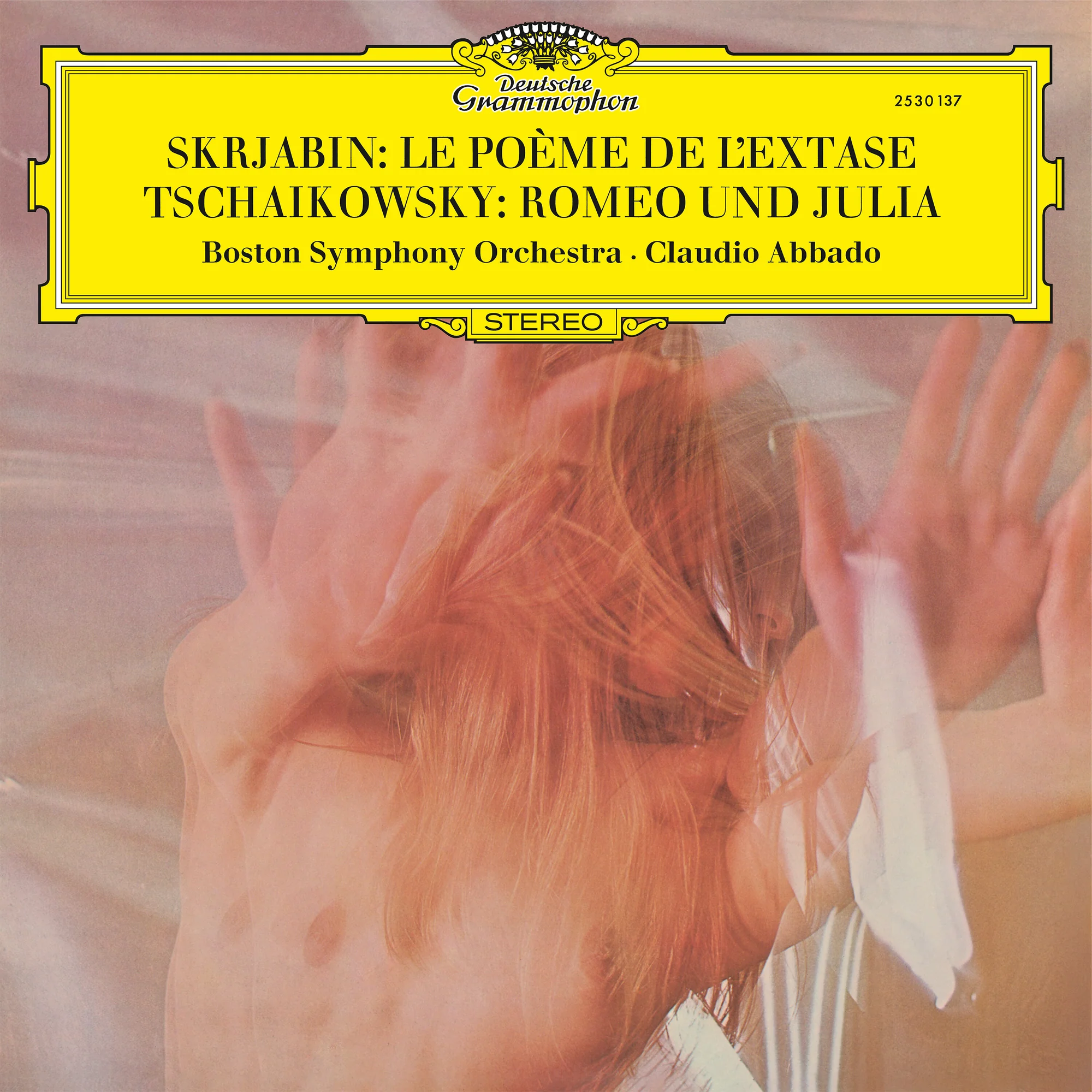

Eroticism and Violent Passion get Super Charged in this Reissue from the Boston Symphony and Claudio Abbado

Tristan und Isolde in Wieland Wagner's landmark 1962 production at Bayreuth

Tristan und Isolde in Wieland Wagner's landmark 1962 production at Bayreuth

Ever since Wagner showed the world how to write 4-plus hours of delayed musical orgasm in his opera Tristan und Isolde, the more hedonistic, “let-it-all-hang-out” chapter of the classical fraternity seemed to enter into an ever intensifying, ever expanding competition to see who could out-raunch and out-sexy their fellow sensualists.

Richard Strauss has got sex everywhere in his music. There’s that whole teenager making love to the severed head of John the Baptist thing going on in Salome (And yes, she definitely gets off before being crushed by Herod’s soldiers - listen to the music). There’s the preamble to Der Rosenkavalier which is a blow-by-blow account of foreplay, sustained humping and “Do you come here often?” - plus post-coital bliss. (Again, the music could hardly be more graphic).

In Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring a girl dances herself into a sexual frenzy of death to propitiate the Gods of earthly renewal. In Carl Orff’s Carmina Burana, the “Love” section concludes with the soprano soloist singing her Big O into the stratosphere (no one “comes close” to Gundula Janowitz on Eugen Jochum’s unequalled DG recording - “I’ll have what she’s having” indeed).

Even that respectable old grandfather of modern music, Uncle Arnold Schoenberg, vented his sensual side in Gurrelieder and Verklärte Nacht. And Ravel gave us a full-blown orgy in the closing pages of Daphnis et Chloé.

Daphnis et Chloé (Ballets de Monte-Carlo)

Daphnis et Chloé (Ballets de Monte-Carlo)

What was it with those 19th century European gents of a certain age?!

And while we’re talking about such degenerates, let us not exclude our two randy composers contained on the record under review here: Mr. Tchaikovsky giving the widescreen, technicolor treatment to that most famous pair of star-cross’d lovers; and fellow Slav Mr. Scriabin giving us the most hair-raising, eyeball rolling, toe curling, heart-pounding, sensually overloading multiple musical orgasms of all time (eat your heart out, Dick Wagner) - masquerading as a spiritual awakening (of course).

You think I’m exaggerating. Just wait ’til you drop the needle on this baby…

Of course there was always sex in classical music (duh!). It’s just that it tended to be somewhat more disguised, and also generally subsumed into the more socially acceptable expression of “love”. But music is, if nothing else, the ultimate purveyor of eroticism by virtue of its abstraction - it can suggest everything without being explicit, bypassing societal and personal censors as it jacks directly into the body’s nervous system via the ears. The traditional tonal harmonic system itself is built on our biological, sexual programming: that of attraction (harmonic sounds ie. music) leading to building tension (deviation from the home key, chromaticism), followed by resolution (taking us back to the home key): ie. arousal, stimulation and release.

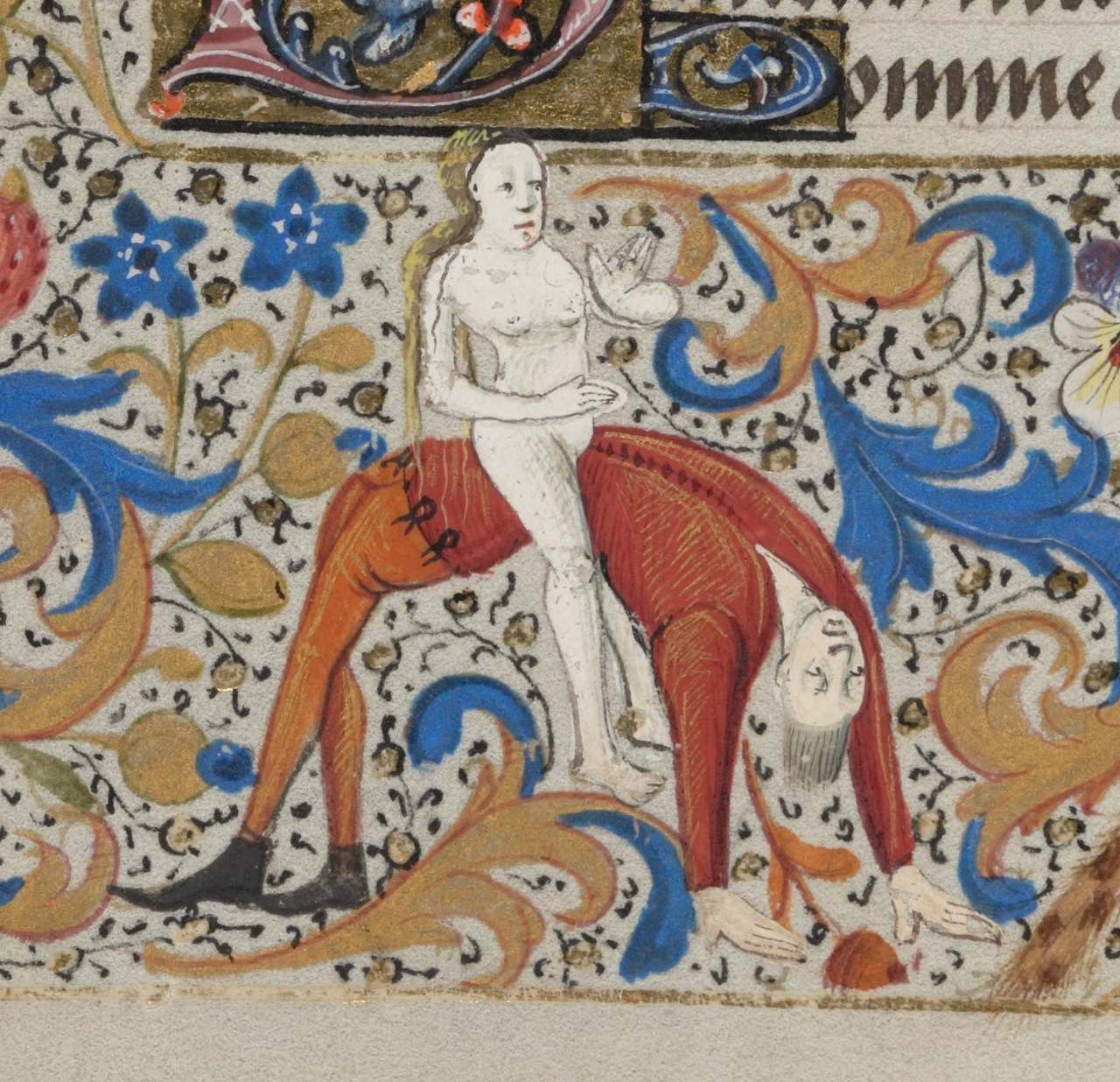

Medieval Kamasutra: Book of Hours, France 15th century. Bibliothèque de Genève

Medieval Kamasutra: Book of Hours, France 15th century. Bibliothèque de Genève

During the Middle Ages when music was closely associated with - and monitored by - the Church, you’d think eroticism would have no chance of finding its way into the cloister. Think again. Expressing one’s love of God and the Divine provides a most convenient pass for writing music evocative of more fleshly pursuits, as a well-regarded musicological tome titled “Music, Body, and Desire in Medieval Culture - Hildegard of Bingen to Chaucer” explored back in 2005 (amazing what one’s research will dig up).

While sex and eroticism were clearly a part of music for centuries, most explicitly in the songs of the Troubadours, art songs, and opera (and, of course, raunchy folk music), it wasn’t until the arrival of Tristan, and Wagner’s revolutionary deconstruction of tonality itself pointing towards a whole new way of thinking about music, that music itself could now sound like sex, like pleasure, like disappearing into total sensual delight. Music could now do that.

How could music do that?

Tristan und Isolde (Salzburg 1972, produced by Karajan, set design Günther Schneider-Siemssen)

Tristan und Isolde (Salzburg 1972, produced by Karajan, set design Günther Schneider-Siemssen)

The sustained edging and final sexual explosion of Tristan was achieved by exploiting tonality’s built-in tension between unresolved harmonic discord and the deep biological need of the human brain to eventually hear tonic/home key resolution to feel “satisfied”. Wagner delays that resolution until the very end of the opera - over four hours in - when Isolde finally finds love in death (singing the Liebestod). (As I am sure many of you are aware, the orgasm itself is often referred to as “the little death”, or “la petite mort” - a phrase we find in literature going back to the 16th century).

Act 2 Love Duet (Salzburg 1972)

Act 2 Love Duet (Salzburg 1972)

In the Act 2 love duet, there is literally a musical coitus interruptus as the lovers are interrupted more or less in flagrante delecto, with a sudden key change just at the point we think the home key is going to assert itself. Wagner was playing that “I can’t get no satisfaction” tune long before the Stones.

Tristan und Isolde (Bayreuth 2023)

Tristan und Isolde (Bayreuth 2023)

The so-called Tristan chord, heard in the first phrase of the opera’s Prelude, encapsulates this whole “endlessly unresolved discord” from the opera’s outset. Wagner’s method pointed the way forward for other composers pushing at the boundaries of tonality to express more earthly delights in a direct manner. It also led to the dissolution of tonality itself, which is a whole other story. The ultimate post-coital comedown, so to speak.

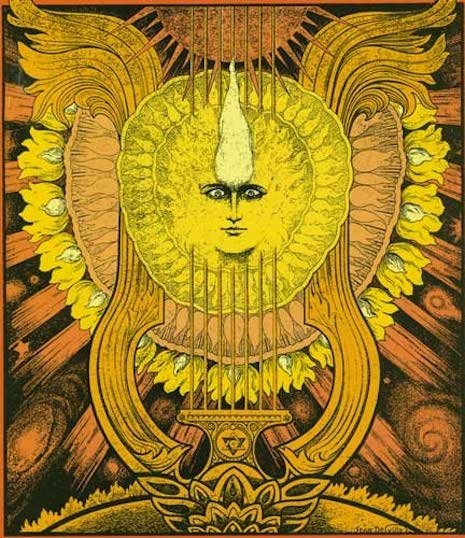

Design by symbolist painter Jean Delville for the score to Scriabin's Prometheus in 1912

Design by symbolist painter Jean Delville for the score to Scriabin's Prometheus in 1912

Which brings us to Scriabin. The Poem of Ecstasy (1908) was, ostensibly, an expression of the composer’s embrace of theosophy, a new quasi-religious/philosophical movement started in America in the 19th century. The program note for the work’s first performance in Russia in 1909 declared:

“Poem of Ecstasy is the joy of liberated action. The Cosmos, i.e., Spirit, is eternal Creation without External Motivation, a Divine Play with Worlds. The Creative Spirit, i.e., the Universe at Play, is not conscious of the absoluteness of its creativeness, having subordinated itself to a Finality and made creativity a means toward an end. The stronger the pulse-beat of life and the more rapid the precipitation of rhythms, the more clearly the awareness comes to the Spirit that is consubstantial with creativity, immanent within itself, and that its life is a play. When the Spirit has attained the supreme culmination of its activity and has been torn away from the embraces of teleology and relativity, when it has exhausted completely its substance and its liberated active energy, the Time of Ecstasy shall then arrive.”

etcetera, etcetera...

However - the original title Scriabin had in mind for this work was Poème Orgiaque (Orgiastic Poem). Need I say more?

He composed it while living in Genoa with his mistress, hiding from the censorious gaze of Russian society and planning to leave his wife. No prizes for guessing what was most on his mind at the time.

Scriabin with his mistress Tatiana Schlözer

Scriabin with his mistress Tatiana Schlözer

Well, the music will tell you all about it. The Tristan procedure of suspending tonal resolution had marked Scriabin’s method for years in his exquisite piano music, and here it is dialed up to the max. The work is one long yearning sigh after another, slowly building more and more tension and expectation of climax - which doesn’t come - and doesn’t come. Until, of course, it finally does come. Multiple times.

The orchestration is a wet dream in and of itself, with the music being endlessly bandied around the different instruments as if they are all trying to seduce each other.

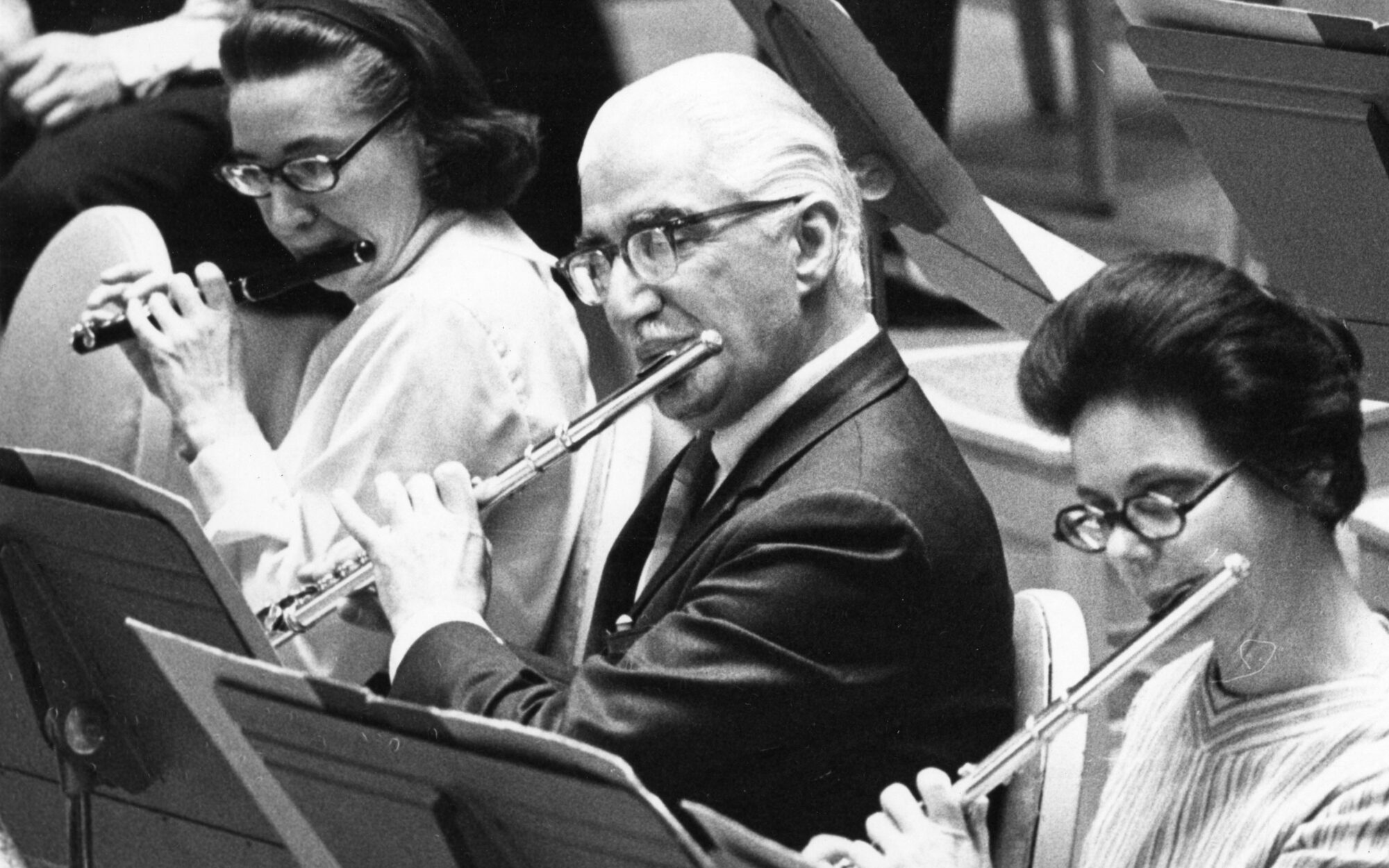

The flute section of the BSO in the 1970s: (l. to. r.) Lois Schaefer, James Pappoutsakis, Doriot Anthony Dwyer. Dwyer joined the BSO in 1952 as its first woman principal player, a position she would hold for 38 years

The flute section of the BSO in the 1970s: (l. to. r.) Lois Schaefer, James Pappoutsakis, Doriot Anthony Dwyer. Dwyer joined the BSO in 1952 as its first woman principal player, a position she would hold for 38 years

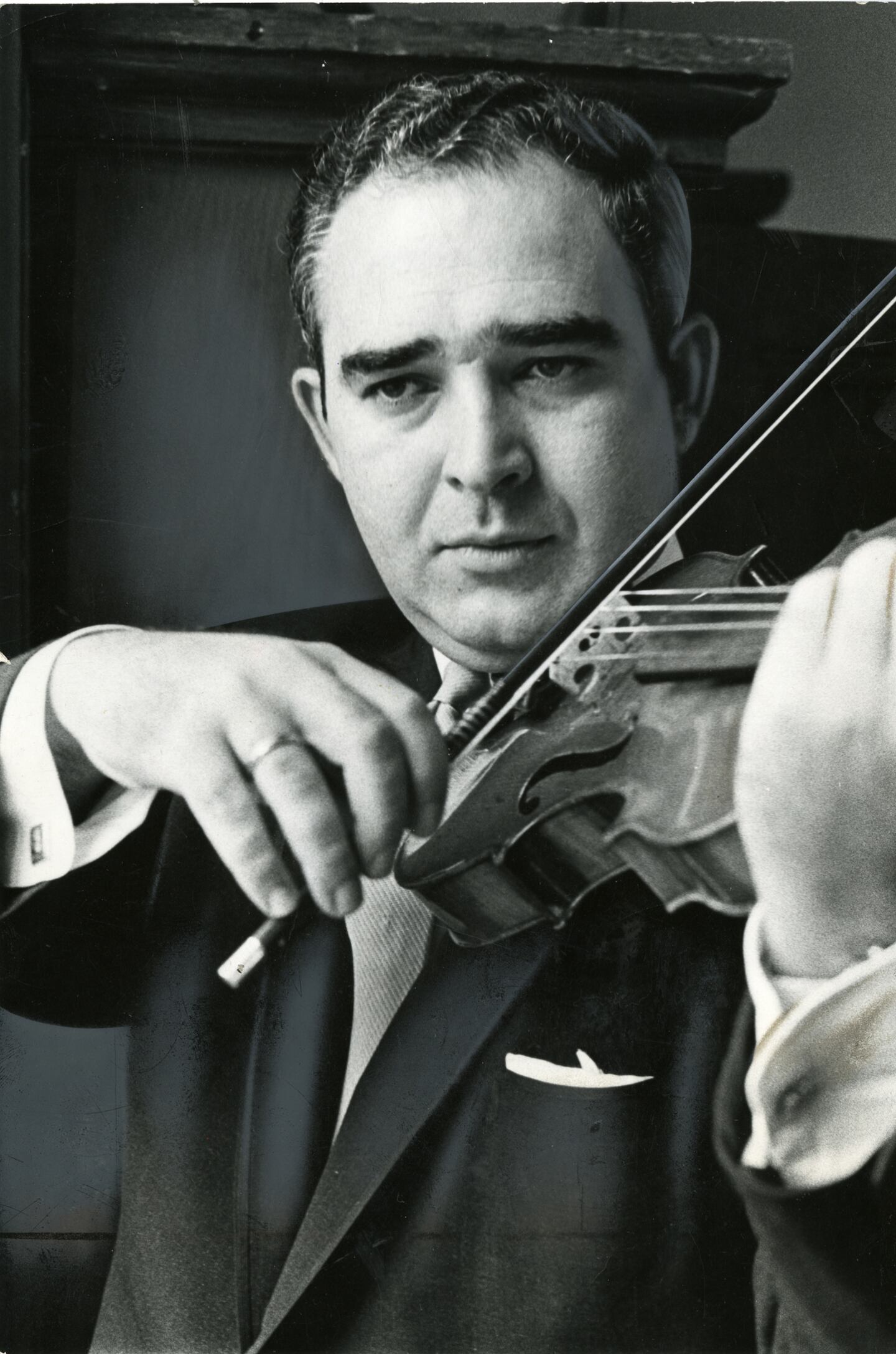

One of the most striking features of this recording is the chamber-like quality of much of this interplay, with the exquisite winds of the Boston Symphony caressing and cajoling to the manner born, while the solo violin of concertmaster Joseph Silverstein dips and weaves seductively.

Joseph Silverstein

Joseph Silverstein

The surges of the full orchestra are electrifying, topped by the incandescent solo trumpet playing of (I would imagine) Armando Ghitalla - the solo trumpet is a prominent feature of this work (and usually credited, but not so here).

Armando Ghitalla (with Pierre Monteux)

Armando Ghitalla (with Pierre Monteux)

In this superb Original Source reissue, mastered and cut directly from the original 4-track master tapes by the gang at Emil Berliner Studios - Rainer Maillard and Sidney C. Meyer - the sound is so massive, so three-dimensional it will threaten to overwhelm your listening room and expand well beyond. Unbridled eroticism will tend to do that… The only shortcoming is a noticeable lack of deeper bass, a quality encountered in the earlier Original Source release of Abbado’s Debussy/Ravel disc, also from Boston. (It’s the reason the Sound score drops to a 9).

But I must say that at a certain point the lack of bass became irrelevant as I was so thoroughly swept up into this performance. In particular I found myself mesmerized by all the subtle interplay alluded to earlier, marveling at the sheer beauty of the solo contributions, then was carried away on the vast tidal wave surges of full orchestral bombast. The score’s markings, which include “very perfumed,” “with a feeling of growing intoxication,” and “with a sensual pleasure becoming more and more ecstatic” - are fully conveyed here.

The thing about Claudio Abbado as a conductor is he can seem like he is a little reticent, prioritizing the letter of the score over any imposed external theatrics, but when that score calls for precisely those theatrics then he is all in. This is one of those performances that delivers it all: the delicate interplay and the massive, thunderous climaxes. And in the Original Source refresh you will find yourself muttering under you breath, not infrequently, “Oh mama!”

_-_(meisterdrucke-1052447).jpeg) Alexander Scriabin

Alexander Scriabin

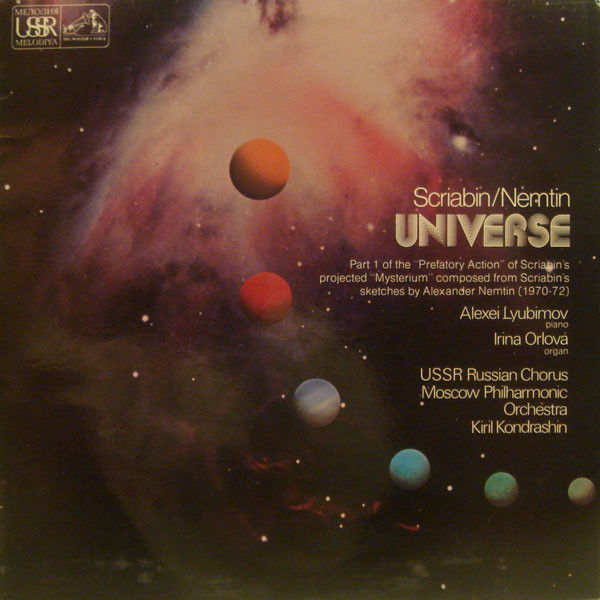

I am something of a Scriabin obsessive. One of my prized record purchases as a teen was of a Melodiya recording of parts of his incomplete work Universe, intended as the first part of a massive multi-media epic titled Mysterium.

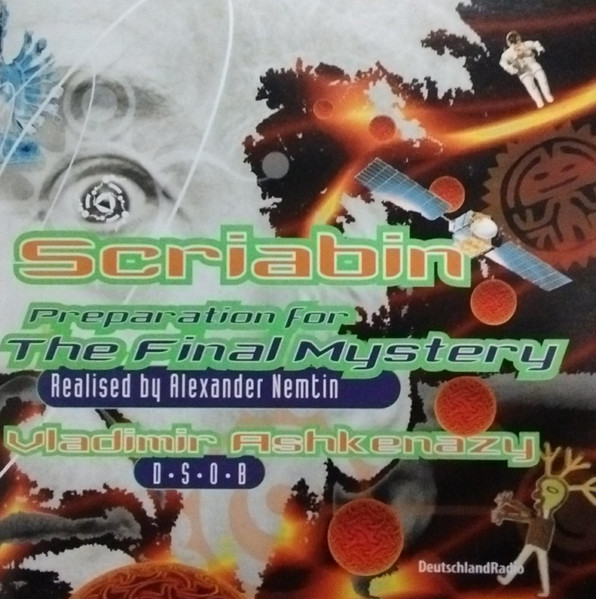

(You can buy the fuller “completed” version on a 3-CD set from Ashkenazy on Decca, also available as part of Decca’s essential bargain box, Scriabin - The Complete Works).

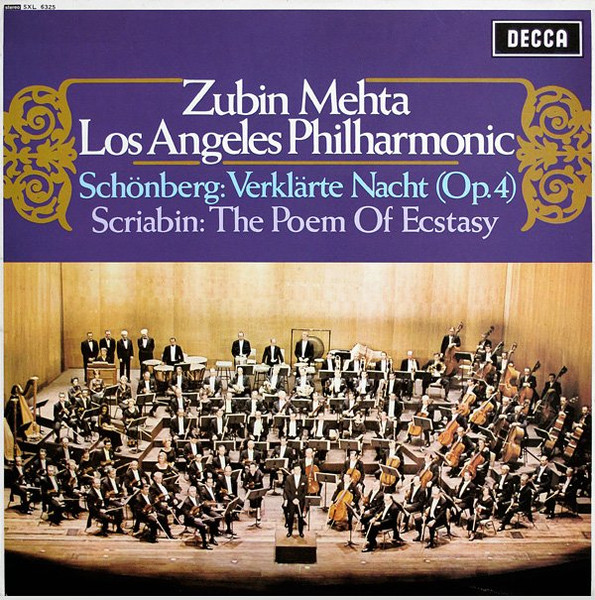

If I see a Scriabin record I don’t already know of in the used bins, into the basket it goes. So I have quite a few recordings of The Poem of Ecstasy, one of which in particular would be considered an audiophile classic, that by Zubin Mehta and the Los Angeles Philharmonic recorded by Decca in Royce Hall in 1967.

But, as I listened to this Abbado record, and as I was left gasping for breath during the final crescendoing climax that seems to go on and on and on, I found my old allegiances cast aside.

I’d found my new flame - and she was hot!

Once I regained my breath and composure (ably assisted by a much needed cup of calming tea) I turned to the flip side. I must confess I wasn’t too excited at the prospect of listening to yet another version of Tchaikovsky’s ludicrously popular Romeo and Juliet. (I’ve actually never heard any of this particular DG record before, although I knew of its high reputation).

So imagine my surprise to find myself equally gripped and blasted by the Tchaikovsky as I was by the Scriabin. And this time the bass is slightly more present, most satisfactorily so.

The sound is big! In the words of Douglas Adams, who was describing Space in The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy: “You won’t believe how vastly, hugely, mind-bogglingly big it is.”

The soundstage is so three-dimensional, so all-enveloping, that when things really get going during the bristling fight music of the street brawls of the Montagues and Capulets you’ll be reaching for your own sword to join in. During the swooning love music you will blush at the intensity and intimacy of the moment.

The famous painting of Romeo and Juliet by Frank Dicksee from 1859

The famous painting of Romeo and Juliet by Frank Dicksee from 1859

The eroticism in Tchaikovsky’s work is of a different order to Scriabin’s: more formalized, more constrained and “made decent”. But make no mistake - Tchaikovsky is definitely channeling his inner bedroom beast. At the time of the work’s composition he was madly in love with Edouard Sack, a young former student - though whether this was requited or even consummated is unclear. What is clear, at least to this listener, is that the intensity of Romeo and Juliet is derived from the composer’s own deeply conflicted passions: even the fight music can be heard as an extension of the love music, in which Tchaikovsky is battling with his own erotic desires. The serenity at the end - as the lovers leave all the turmoil behind and are united forever - can also be heard as the composer’s yearning for a state of equanimity beyond earthly passions.

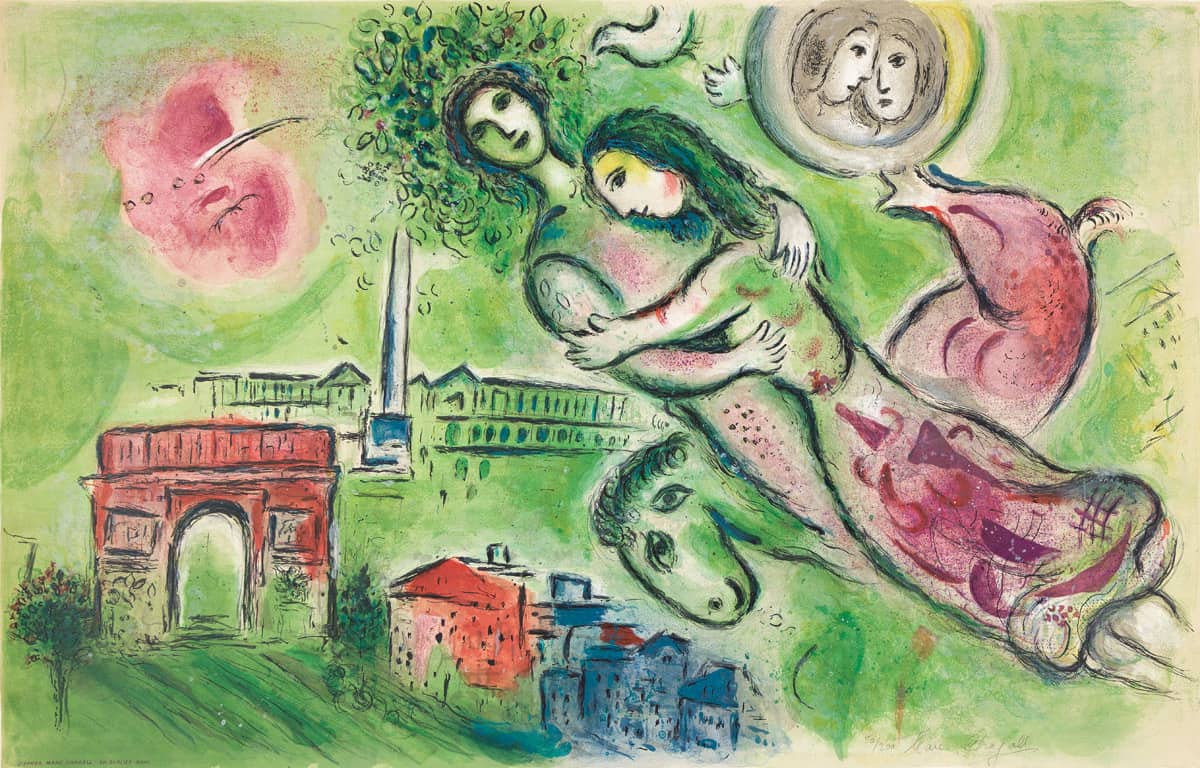

Romeo and Juliet lithograph by Chagall

Romeo and Juliet lithograph by Chagall

It is incredible to think that this most popular work of the composer was so hard for him to compose, even harder than the First Symphony of a few years earlier. It essentially went through three versions over the course of 27 years, guided throughout by the suggestions of Mily Balakirev (1837 - 1910) - the putative leader of the “Five” group of composers dedicated to finding a more authentically Nationalistic voice in Russian music. Even after the many years of revisions, the work struggled to find popularity.

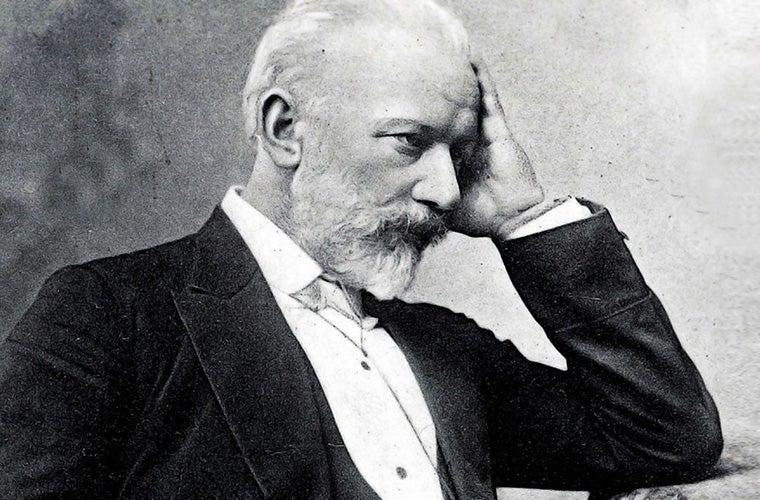

Peter Tchaikovsky

Peter Tchaikovsky

There’s no mistaking the fierce conflict and erotic charge - as well as the soaring love passion - in Abbado's and the Bostonians’ commitment to every heart-on-the-sleeve moment in Tchaikovsky’s super-charged tone poem. When the brass and percussion kick in during the fight sequences, Holy Mama is this thing going to send your heart racing as it did mine!

So, apart from my slight caveat about the rolled-off bass in the Scriabin, this is a self-recommending record even to those of you who would be quite happy never to have to hear Tchaikovsky’s Romeo and Juliet ever again.

As for The Poem of Ecstasy - close the door, dim the lights and close your eyes…

It’s toe-curling time!

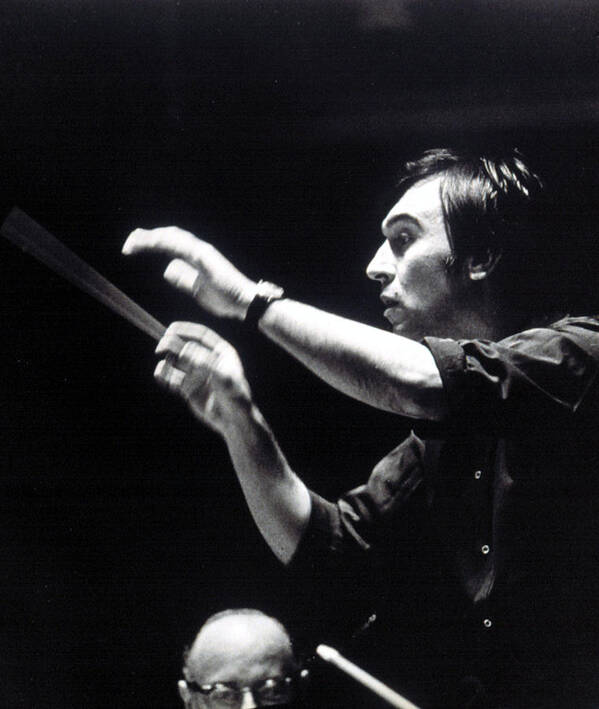

Claudio Abbado

Claudio Abbado

.png)