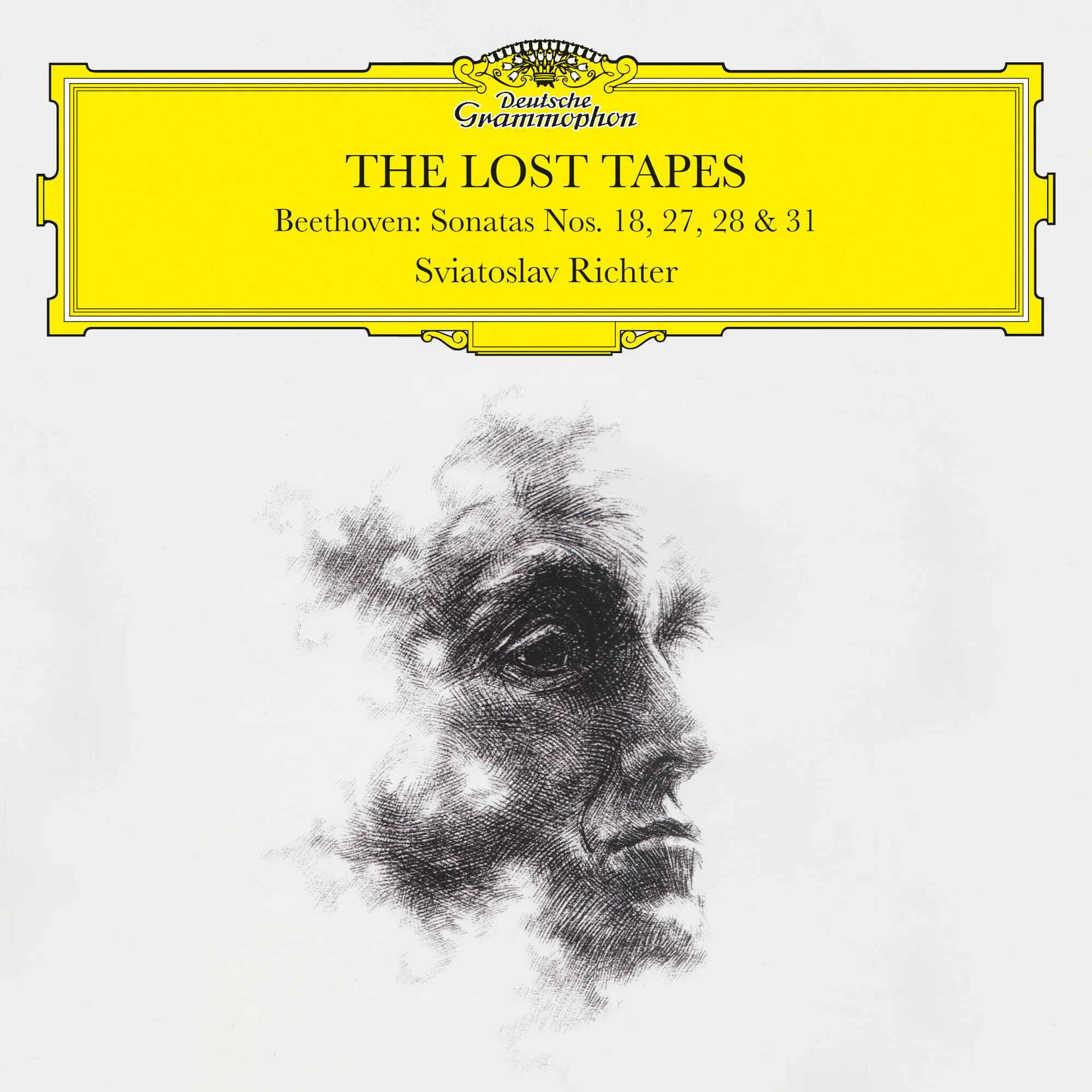

Titanic Beethoven from Sviatoslav Richter Restored to Catalogue

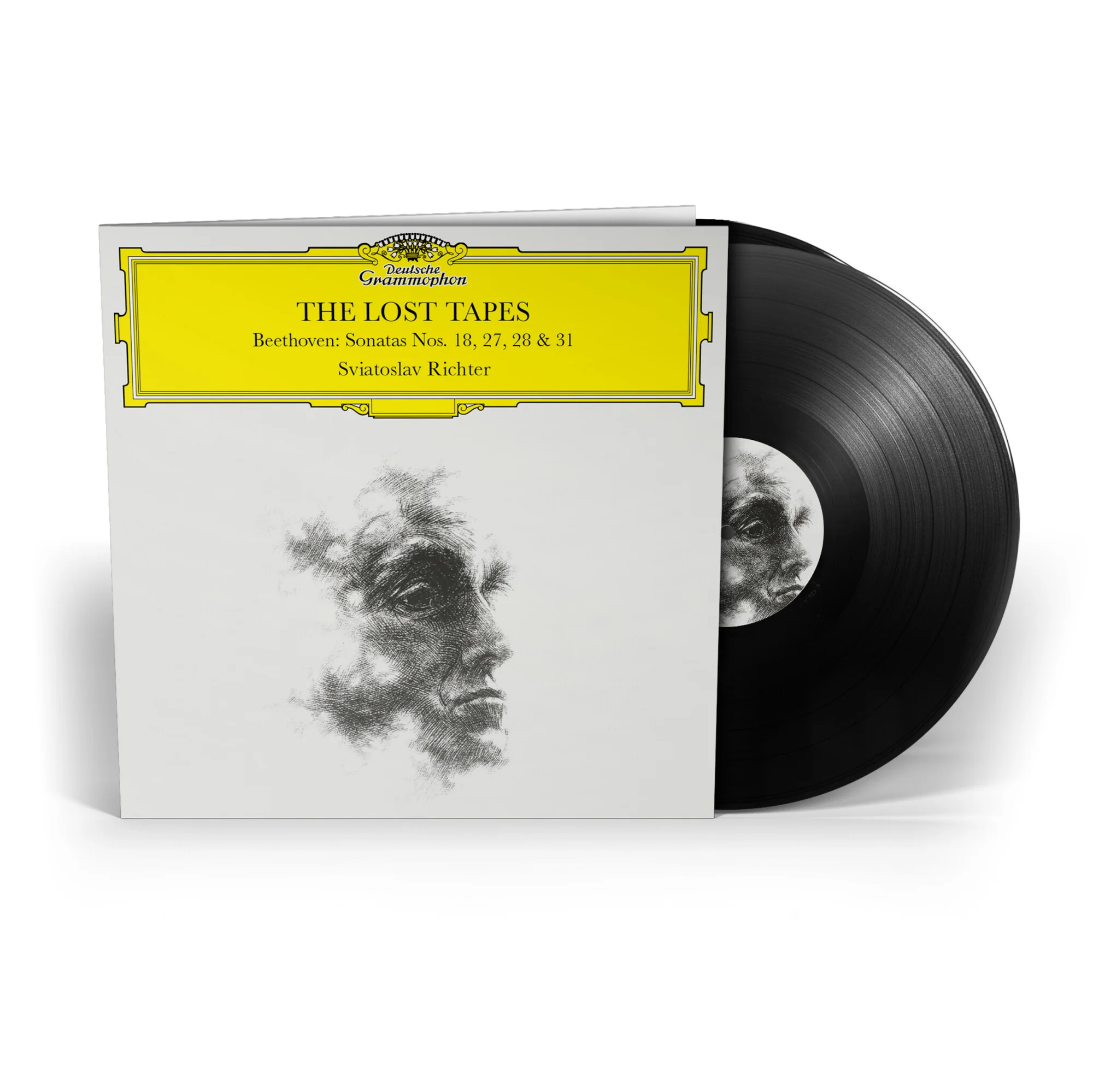

“The Lost Tapes” brings us previously unreleased recordings of the great Russian virtuoso performing “live” in his prime

This is a very special release.

No, it’s not an “audiophile” release as such, but the sound is thoroughly acceptable and engaging for a historic “live” taping. It fully conveys everything it needs to convey about these musically stunning performances, three of which, incredibly, were recorded on the same evening.

For anyone remotely interested in hearing one of the titans of the keyboard on top form in some of the finest piano music ever written, this is a mandatory purchase. I don’t care how many recordings you already own of these works, this is completely in a class of its own.

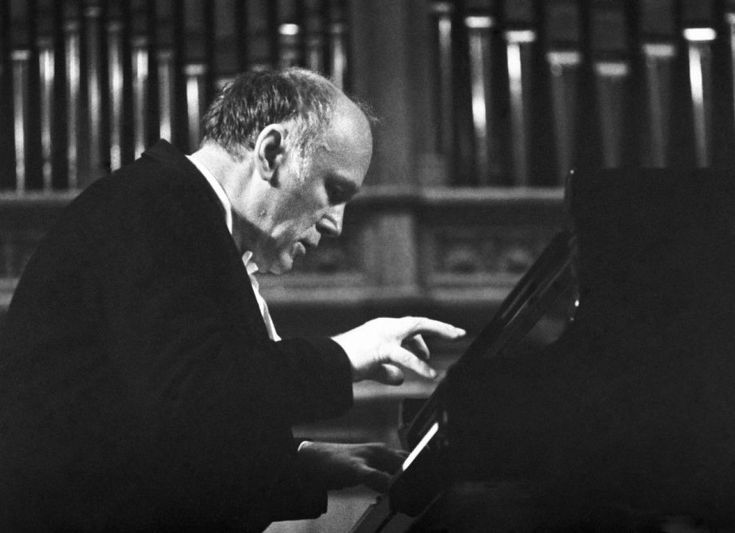

Sviatoslav Richter

Sviatoslav Richter

I actually heard Sviatoslav Richter perform live in concert when I was around 15, and it remains an indelible memory. My school sponsored a concert series which brought many of the world’s finest pianists to our school hall, performing on our Steinway concert grand. Since I am no spring chicken (though often imagine myself to be otherwise), this means that I got to hear the grand older generation of virtuosos, sitting behind them onstage, about 12 feet from the piano with a clear view of their hands on the keyboard. Thus I heard the immortal Arthur Rubinstein in his twilight years, Emil Gilels, Shura Cherkassky, a younger Alfred Brendel, and more. But Richter’s visit sent an extra thrum of anticipatory excitement through the school community and beyond. The hall was packed to hear him play, amongst other things, that virtuoso showpiece, Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition. And he did not disappoint. His appearance was everything you might expect from the Russian firebrand who had already astonished audiences around the world for several decades. He dominated the keyboard in a manner I have never seen nor heard since. The Russian bear unleashed.

There was just one problem: he was not playing our school Steinway, but a decidedly inferior-sounding Yamaha piano that traveled with him because of his lucrative deal to promote what was then a new entry into the piano manufacturing marketplace. At this time, around 1975, Yamahas were not the quality instruments they are today, when they often supplant Steinways in the world’s concert halls and recording studios. Yamahas back then were decidedly undernourished in their sonorities, and throughout Richter’s concert there was a sense of his sound being “cabined, cribbed, confined”, with dynamics compromised and his expressive range limited. I remember my piano teacher muttering words to the effect of “If only he was playing the bloody Steinway!”

Nevertheless, it was evident from first note to last we were in the presence of one of those unique musical forces that do not come around too often. For many, Richter is up there with Vladimir Horowitz, two titans amongst giants.

His catalogue contains a fair share of studio classics, but it is bursting at the seams with live releases and bootlegs. Richter himself always felt that he was at his best live, where he was able to marry his deeply prepared interpretations (practiced over and over again at length), with the frisson of the live event. If you want to disappear down the rabbit hole of his catalogue of live recordings, appearing on multiple labels, official and unofficial, you will not be heard from for years.

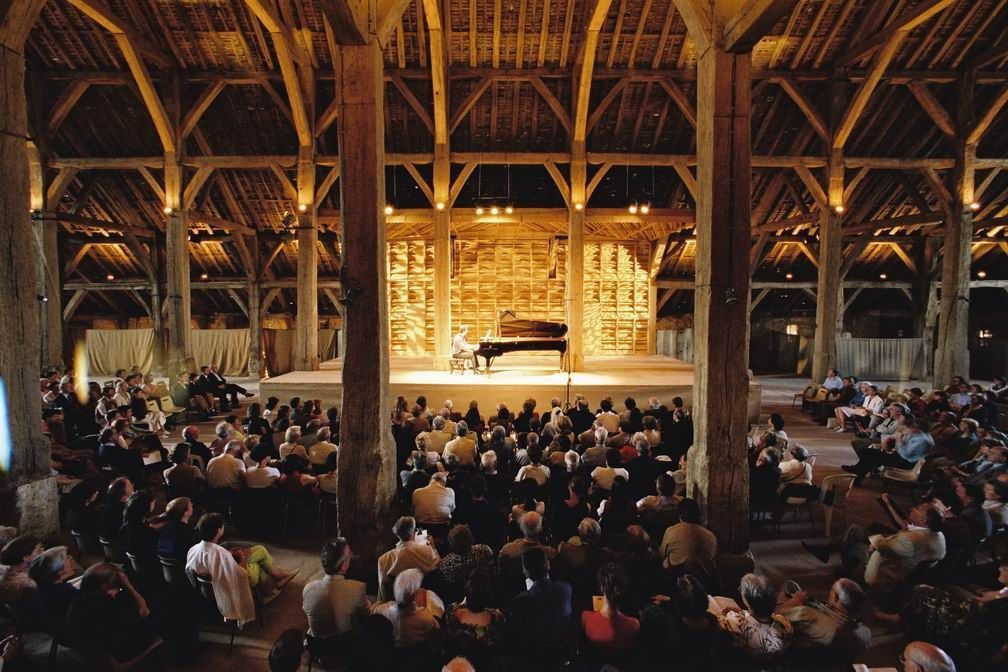

Inevitably, many of these recordings are of dubious technical quality, with intrusive audience noise. How remarkable, then, to be able to listen to the performances on this double LP set captured during Richter’s prime, in quality “official” recordings made by “his” label, Deutsche Grammophon’s top engineers, but never released (though test pressings did circulate in the offices of DG, to the wonder of all who heard them). They derive from performances in 1965 at the Lucerne Festival on 2nd September (op. 31/3, op. 90, op. 101), and Richter’s own festival at La Grange de Meslay, near Tours, on June 29th (op. 110), which took place in an old converted barn, where the local owl would sometimes be heard "snoring" during the proceedings.

The converted barn at La Grange de Meslay, now a concert hall

The converted barn at La Grange de Meslay, now a concert hall

Let’s talk about the sound. Yes, these are definitely better than most live tapes you will hear from this period, but this is still not studio quality piano sound, and that is partly because of the Lucerne instrument used for three of the four sonatas, which leans towards a somewhat bright, metallic treble register (the other piano, recorded at La Grange du Meslay, is a touch mellower). Nor is there the kind of deep bass you would expect from a studio session of the time (though in its studio LP releases DG always leaned towards a lighter bass in its piano recordings). However, the wizards at Emil Berliner Studios have done a fantastic job of ameliorating that treble brightness to the point where the piano tone is very acceptable, and actually in many ways resembles quite a modern sound, with intimations of an instrument with hints of a period “fortepiano” tone (as much owing to Richter's brilliantly articulated finger work). Inner detail in the part-writing emerges clear as a bell, with no sustain pedal smudging, and Richter’s superhuman articulation of rapid passagework and trills is, frankly, a miracle to behold. It never intrudes on the overall musical line, but is there in all its minute detail, making the pulse quicken thrillingly. His legato is impeccable, melting but never cloying, achieved again, it seems, with a minimal amount of pedaling (or rather pedaling that is so discrete as to be inaudible). One can only imagine what Beethoven would have thought had he been able to hear playing like this.

My only slight quibble with the sound - and this is largely a matter of personal taste - is that it is very clearly evident, even without being told, that these are live performances, and yet great effort has been made to eradicate any trace of audience noise, including what I imagine would have been vociferous applause at the end of each sonata. This is very much the current trend amongst releases of live records: to take out the applause and to make the audience “disappear” as much as possible. I do not hold with it at all. I feel that the frisson of the presence of a live audience is an integral part of the aesthetic experience of these live events, and I really miss hearing the sonic signature of the audience “jumping to its feet” at the conclusion of Richter’s performances. (And I also wondered occasionally whether all this digital cleansing had robbed the sound of an ounce or two of the vitality of nature’s imperfections which would have been present on the original tapes). Just to give one example in this set of the regrettable absence of applause: the Presto con Fuoco finale to Sonata No 18, “The Hunt”, is what lends the piece its nickname, and more thrilling a musical depiction of horses, riders and hounds in grand pursuit across field and dale is impossible to imagine. Richter’s performance is superhuman in its gallop, and as it leaps and bounds to its victorious conclusion all you want and expect to hear is the roar of the crowd’s approbation - which, alas, never comes. The deafening silence is inadequate to the moment. A real misjudgment here, at least for this listener, to leave out the applause.

Oh, but this is merely a quibble in the face of such glorious music-making, which somehow manages to encompass both daredevil-may-care, “throw caution to the winds” spontaneity and Classical poise. Interestingly, I found myself reminded over and over again of Haydn, and it made me long to hear Richter play those infinitely rewarding sonatas by Beethoven's one-time teacher. (There is definitely more than a trace of Haydn-esque wit in these works, though presented with a more serious cadence).

Richter is deeply embedded in Beethoven’s idiom, derived from years of close study of the scores: Classical in their roots, Romantic in their aspirations, straining at and ultimately breaking the shackles of the age’s musical custom and form. In short, this is Beethoven’s extraordinary piano sonatas captured in all their many facets - embodied in a manner that feels at once profoundly authentic, more than a little revolutionary, and in the end utterly transcendent. The way these works move in one direction and then suddenly shift; the way the seemingly most simple, beguiling utterance can suddenly seem to speak of vast emotional depths - Richter captures all of this variety, all these shifting sands, effortlessly. One moment you feel you are hearing something completely of the Classical period, the next moment moving into the emotionalism of the Romantic period, and the next moment stepping into territory that is completely modern. But always these different strains are contained within a clearly expressed musical argument, with all these disparate elements held in perfect balance.

It all beggars belief that anyone could ever actually play this music like this!!!

-after-a-painting-by-karl-schweninger.png) "Beethoven in the Storm" (c. 19th century lithograph after a painting by Karl Schweninger)

"Beethoven in the Storm" (c. 19th century lithograph after a painting by Karl Schweninger)

From the first few bars of Sonata No. 28, op. 101, it is clear that this is music especially close to Richter’s heart - a fact confirmed upon reading the sleeve notes contained within this release. For this recording of this work alone the set is worth the price of admission. All the late Beethoven piano sonatas enter a new land of musical expression which remains unique to Beethoven lo these many years later. These are works which, no matter how often you listen to them in multiple interpretations, remain challenging, bracing, and ultimately mysterious. But this sonata in particular is otherworldly in its many dimensions, its expressive about-faces. Richter is a compelling guide on the journey through its twists and turns, finding a clear through-line without short-changing the many deviations along the route, even as he declares in his sleeve note that he finds it “horribly difficult”.

In that same sleeve note, Richter reveals he had no great desire to ever learn the Sonata No. 31, op. 110, which concludes this set, but he was forced into it by his great and revered teacher at the Moscow Conservatory, Heinrich Neuhaus. He goes on to write that “with the op.110 Sonata, Neuhaus taught me to obtain a singing tone, the tone that I’d always dreamed of. It was probably already in me, but he freed it by loosening my hands and teaching me to open up my shoulders. He helped me get rid of the harsh sound that was a legacy of the time I’d spent as a répétiteur at the Opera”. [A répétiteur accompanies all opera rehearsals on the piano, and is one of the jobs that many future conductors hold during their early years. Richter started working at the Odessa Opera when he was 15, sight reading complicated scores of all types].

Listening to this performance of op.111 you’d be hard pressed to detect any reticence on Richter’s part to engage with this work. The manner in which he brings everything to a head in the final titanic Fuga, in which he alternates between massive organ-like statements of the fugal subject and passages dripping with that hard-earned “singing tone” will leave you aghast. This is piano playing - Beethoven playing - like no other.

Lucerne in the 1960s, where most of these recordings took place

Lucerne in the 1960s, where most of these recordings took place

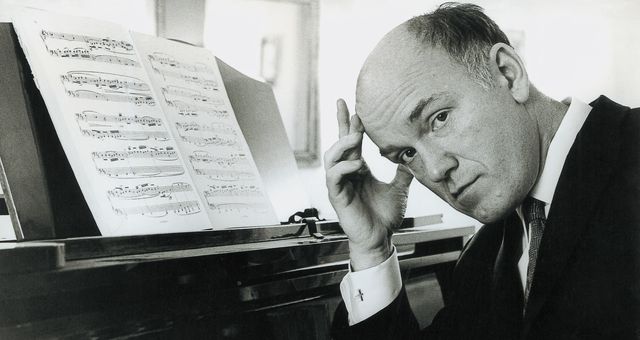

A quick word about the exquisite presentation and documentation of this set. The gatefold jacket is of the same matte finish as the Original Source reissues (although this is not an Original Source release, the immaculately pressed platters are cut to the same level of perfection we are used to in that series, by Sidney C. Meyer at Emil Berliner Studios). The cover features a remarkable line drawing of Richter by Peter Reuter dating from 1965. Packaging lends the release a classy archival quality - this is a lovely set to hold in your hands.

Evocative archival photos of Richter and the DG engineering team pepper informative program notes. (Though the photo of Richter accepting vociferous applause at concert’s end in Lucerne only underlines the disconcerting absence of applause on the records themselves).

Richter at the end of a concert in Lucerne (photo: Josef Koch)

Richter at the end of a concert in Lucerne (photo: Josef Koch)

Product Manager Markus Kettner outlines the story behind the tapes, and offers some keen insights into the bond between Richter and Beethoven’s music. Jed Distler, the doyen of piano music criticism, contributes an equally insightful assessment of these performances and their place in the enormous Richter discography - a very welcome orientation for comparative Richter neophytes like myself. A note from Richter himself is supplemented by an extended conversation with the fine pianist Elizabeth Leonskaja, who knew Richter well and administers his artistic legacy. Her remarks reveal much about the man and the artist that is fascinating, and add greatly to one’s appreciation of these recordings. I will leave you with these comments of hers pertaining to what made Richter’s Beethoven performances so special:

“Three things: his interpretative powers, his vision, and his conviction. I think that with these resources he was able to delve into these works to a degree that was almost perfect… It’s all about energy. Richter was an unusually powerful pianist. I don’t mean this in the sense of a powerful attack but in the sense of his ability to explore every facet of a work. I remember him giving a concert in Leningrad to mark Evgeny Mravinsky’s 80th birthday and Mravinsky was asked about his work. Mravinsky said: ‘I can’t prove anything. I can only persuade people.’ That’s what it is. You just have to be a great artist to get this.”

Available now directly from the DG webstore (on regular and limited edition vinyl, and CD) and available in the US at Acoustic Sounds and Elusive Disc.

.png)