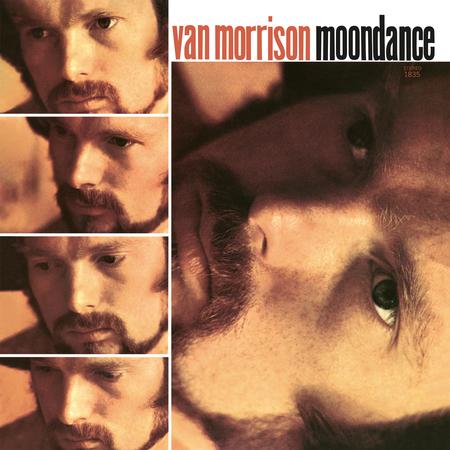

Van's Earthy, Mystical Masterpiece Gets a Double 45 Release

back to basics after inexplicable "Astral Weeks" flop

Following the commercial flop of Astral Weeks, his moody, mystical, musically eclectic masterpiece, that years later found its commercial footing, to detach themselves from New York City chaos, Van Morrison and wife Janet (Rigsbee) Planet moved to the Catskill Mountains near the town of Woodstock, New York.

Earlier, following the break up of his group Them, he'd signed a contract with Bert Berns's Bang Records and in March of 1967 entered famed A&R Studios intending to record a quartet of singles, one of which, originally titled "Brown Skinned Girl" became "Brown Eyed Girl". Whatever problems Van had with Berns, he knew how to produce a tune. Berns had hired top studio musicians including Eric Gale, Hugh McCracken and Russ Savakas, and to sing backup, The Sweet Inspirations—Cissy Houston, Dee Dee Warwick and Myrna Smith.

Bert and Van didn't get along, Van was difficult then, and of course continued to be, but a sufficient number of tracks had been recorded to release Blowin' Your Mind. Van on tour at the time was unaware of the release and he wasn't happy about it. The two met up later and Berns suggested they book time at A&R and begin recording another album.

Things again didn't go well, though Morrison had laid down an early version of the astonishing "Madame George", "Beside You" and other bits of music that would later find their way into Astral Weeks.

Then Berns had a heart attack and died. Wife Eileen took over but Warner Brothers' exec Joe Smith moved in and signed Van, who still owed Bang an album. Van quickly and cynically put one together and submitted it to cover the obligation. The "songs" were dozens of short jams with titles that included, for example "Blow in Your Nose", "Nose in Your Blow", "Want a Danish" and "Ringworm". All of the Bang and subsequent tracks were released on a 3 LP set on the Italian Get Back label and later on various CD sets.

No wonder following the lack of commercial acceptance for his Astral Weeks masterpiece and all that had gone down, Van moved upstate where he put together a new band more to his liking and wrote and rehearsed material for Moondance—an R&B influenced collection of spiritually affirmative, more "earthbound" tunes compared to Astral Weeks. He was at that time a happily married man. Production commenced at New York's Century Sound Studios with many of the same jazz musicians who played on Astral Weeks, and engineer Brooks Arthur.

Van wanted out of the scenario that producer Lewis Merenstein, who did same on Astral Weeks had arranged, so he abandoned the project there and moved back to Phil Ramone's legendary A&R Studios, where spectacular sounding albums like Getz/Gilberto had been recorded years earlier. He got the R&B sound he wanted using a pair of saxophone players he'd worked with following his upstate move plus a basic rhythm section of keyboard, guitar, bass and drums.

The songs weren't fully written but the ideas had been hatched and in the studio Van and his players put it all together and how. Sitting at the board were Tony May, who had worked with Brooks Arthur at Mira Sound in the Hotel Americana, Elliot Scheiner (incorrectly spelled "Schierer" on the original and every jacket since), Shelly Yakus, who like Scheiner needs no introduction, Neil Schwartz and Steve Friedberg.

There's a great deal of mystery surrounding the album's recording. In interviews Scheiner remembers that most of the tracks were cut live, with some overdubs. He recalls that at the time A&R would assign engineers to record at different times, which explains why so many are listed in the credits. He also claims that the song "Moondance" was not recorded at A&R. When he went to re-mix the title track for a surround release Neil Schwartz was listed as the engineer.

Another A&R engineer, Dixon Van Winkle remembers it differently (his credits include mixing McCartney's "Uncle Albert"). He claims Tony May engineered it at A&R. If you're interested in this history there's a fascinating series of interviews about it in Mix Magazine part of a story by Gary Eskow.

The release in America end of February 1970 was met with unanimous well deserved praise from all of the rock critics at the time and for good reason. No point in going over that. It's too late to start now— other than to write that Van was in fabulous voice, the songs covered everything from domestic bliss to spiritual transcendence and the music was R&B infused rock with some jazz tossed in. The record holds up as well today as when it was first released, perhaps even better, the more you dig into the arrangements. You could even say it was "fantabulous."

This is an album that always sounded good, but never great, which was disappointing and odd given who was at the board and where it was recorded. It always sounded as if it was holding back dynamics, detail and upper frequencies, though it sounded "good", with an appropriately "organic" and natural timbral palette and if you cranked it well up it displayed more sonic vitality, which isn't always the case.

I've got multiple copies including more than a few -1A WB Keystone copies and even a 1C Warner 7-Arts label copy even though by that time the company was Warner Brothers Records. I also have the DirectDisk edition so I'm well acquainted. I also have the edition Tom Biery produced for Warner Brothers years ago when the label didn't care much about vinyl.

When Analogue Productions asked for the master tape to produce this record Chad Kassem was told he had two choices: one was the equalized production master used for the original pressing, also used by everyone from that time forward (and of course copies of that for overseas production), or, Chad was told, a carefully produced flat transfer of the master tape at 192/24 bit resolution produced within the past decade.

The unequalized tape (beyond what Scheiner had done in the final mix), was not among the options Warner Records offered. An explanation wasn't offered so one has to assume the label didn’t want to send out the tape because it probably had suffered some damage or perhaps it's fragile and they didn’t want to take a chance with it.

It's not as if Warner Music is against "cut and splice" operations, so whatever the possible problems, they must be more substantial than, for instance, those on the Fleetwood Mac masters where a copy was used by Kevin Gray to make "cut ins" to replace bad sections (or whole tracks) so the actual master could be used. Here that wasn't possible.

Chad and his team asked for the equalized production master tape and for a clone of the high resolution file. For Analogue Productions to release a record from a digital file was a painful decision. Before going that route, Chad cut lacquers, plated them and auditioned new pressings made from the original equalized (and limited) copy—a process more affordable when you own the mastering system the plating facility and the presses— and not surprisingly the records sounded like original pressings, though not quite as good because the tapes were 50+ years older. But they sounded good and familiar.

Chad and team then worked with the files, which without any equalization sounded to their surprise considerably better than the best original pressing they had in-house. The master tape had considerably wider dynamic range and frequency response than the production master, which someone had used a pretty heavy hand to produce. Still the file needed some EQ work to whip it into Analogue Productions quality shape and the AP team worked for quite some time getting the sound to their liking.

I admit here that Chad sent me various iterations of this production all along the way asking for my opinions, which I gave him, so consider this self-serving if you insist: but this new double 45 edition is more dynamic, delivers greater detail and lifts more than a few veils of murk from atop the music that were hiding underneath. Part of it could be ascribed to the move from 33 1/3 to 45 but mostly it's clearly better because the source wasn't a tape copy that had been equalized and limited by whoever did it back in 1970 and felt it had to be done to make it playable or whatever the reason or reasons it was done.

Do I hear "digititis"? No. Is there a feeling that the flow isn't quite as intense as on the all analog versions? Sometimes I felt that but mostly I thought that feeling was a "plug in" of my invention. Before you say "Well than why bother with tape in the first place? Why not just cut everything from a file like 'some others' do?".

My answer would be: you (or someone) pay to do it both ways using a highly regarded well loved recording, one cut from a tape in excellent shape, and one from a file and let's see how people react. In fact, I once proposed that to Chad using a famous classical recording but for one reason or another we never got around to doing that.

So I'll conclude by saying that this double 45 edition of Moondance has greater dynamic range, and wider frequency response than any of the original pressings I have and reveals more details, but subtly so, so it will still sound like the record you love. Only better.

.png)