Blu-spec CD2: Any Difference?

An exploration into Sony Japan's Blu-spec CD2 format

Long after the Western world moved to digital downloads and streaming, CDs reigned supreme in Japan; only now is Japan widely adopting music streaming. Western collectors value Japanese CDs for their nicer packaging and apparent sonic superiority, but even in Japan, imported American and European CDs are cheaper than their locally-made counterparts. To encourage domestic purchases, Japanese labels often add bonus tracks and/or nicer packaging, but they also flaunt their specialized, supposedly superior CD manufacturing technologies.

Several major companies have their own CD-making processes used for select titles: Sony has its own Blu-Spec and its successor Blu-Spec CD2; JVC Kenwood, which makes CDs for Universal and Warner, has Super High Material (SHM); and Memory-Tech, whose clients are nearly everyone but Sony, has the Ultimate Hi-Quality CD (UHQCD), the “new and improved” version of the slightly older HQCD (Hi-Quality but apparently not “ultimate”). All adhere to 44.1kHz/16bit Red Book specifications (though single layer SHM-SACDs and cross-compatible MQA-UHQCDs exist), but different CDs with the same mastering can still sound very different. Despite the advertising hype, no one seems to have properly compared these CDs to the equivalent Western editions; therefore, I’m diving headfirst into the world of Japanese CD pressings. This feature focuses on Sony’s Blu-Spec CD2, and is the first in a three-part series also exploring SHM-CDs and UHQCDs.

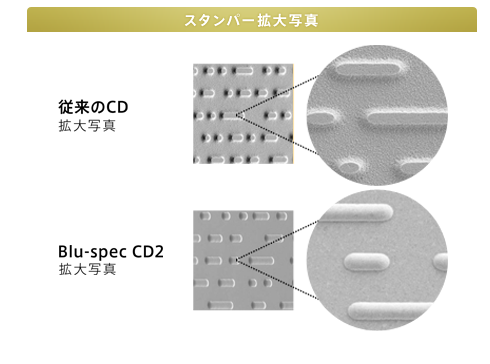

What is Blu-spec CD2?

To understand how any of these technologies work, you first must understand how CDs are made, which isn’t too different from how records are made. With CDs—and all optical media for that matter—the information is laser-etched into a glass master, which is then converted to a stamper that molds the polycarbonate. The polycarbonate represents the data as “pits” (from the label side of a CD, if you could see through it) or “bumps” (the perspective from the playback side), and is then coated with a reflective aluminum so the playback laser can read the data. Finally, a clear acrylic protective layer is added and the label is silkscreened on. Unlike records, optical discs are manufactured in clean rooms, and the production must be incredibly precise.

CDs hold less data than other optical media because their cutting and playback lasers have longer wavelengths than those for SACDs, DVDs, Blu-rays, etc. Blu-spec CDs are cut using the finer lasers used for Blu-ray cutting, with the idea that this results in a more precise cut of the original data and jitter reduction. Also used here is Phase Transition Mastering, a technically higher quality stamper process developed for Blu-ray production. Sony’s Blu-spec CD2 website also says “the disc material is ‘polymer polycarbonate,’ a high-quality material with a reputation for Blu-spec CD,” though I’m skeptical of anything special here since polycarbonate—a very standard CD material—is a type of polymer. Think of these specialized Japanese CD processes like UHQR’s or One-Steps in the vinyl world; they're still standard Red Book CDs with all the limitations of a CD, but possibly better. (The Blu-spec concept of a more precise master cut could be seen as the CD parallel to half-speed lacquer cutting.) Blu-spec CD2 (BSCD2), the format auditioned here, debuted in 2013 as the successor to the original Blu-spec; anytime I mention Blu-spec, I’m referring to the 2013-onward Blu-spec CD2.

Listening

The first Blu-spec I played was the 2013 edition of 1978’s Pacific by Haruomi Hosono, Shigeru Suzuki, and Tatsuro Yamashita. Originally commissioned for CBS/Sony’s Sound Image series, it’s an instrumental LP that’s supposed to sound like you’re chilling at a beach resort. It succeeds. Sonically, it has that squeaky-clean, dry late-70s studio sound with lots of isolation, but it still sounds cohesive and musical. I didn’t directly compare this with any other version, but through previously hearing the 96kHz/24bit stream I had an idea of how it should sound.

Right from Hosono’s opening track “Saigono Rakuen,” I found myself bored. Digital audio has drastically improved especially in the last two decades and standard-resolution CDs have reaped the trickle-down effects’ benefits. Yet this Pacific Blu-spec had that sterile, dimensionally flat sound that made early CDs so dreadful. Everything was clear, but nothing sounded very real nor did it cohere into an engaging presentation. The Pacific CD continued like this until Hosono’s closing “Cosmic Surfin’” (later rerecorded with Yellow Magic Orchestra), a dizzying display of synth effects. They sound like they’re supposed to jump out at you from the speakers, but they seemed restrained, trapped in this one-dimensional space that doesn’t extend behind or in front of the speakers. When it sounds good, Pacific is a fun and easy album to listen to; the seaside image it conjures up isn’t real but feels as such. The immersive recording is a big factor. The Blu-spec lacked that fun, but blame the mastering, not the format… right?

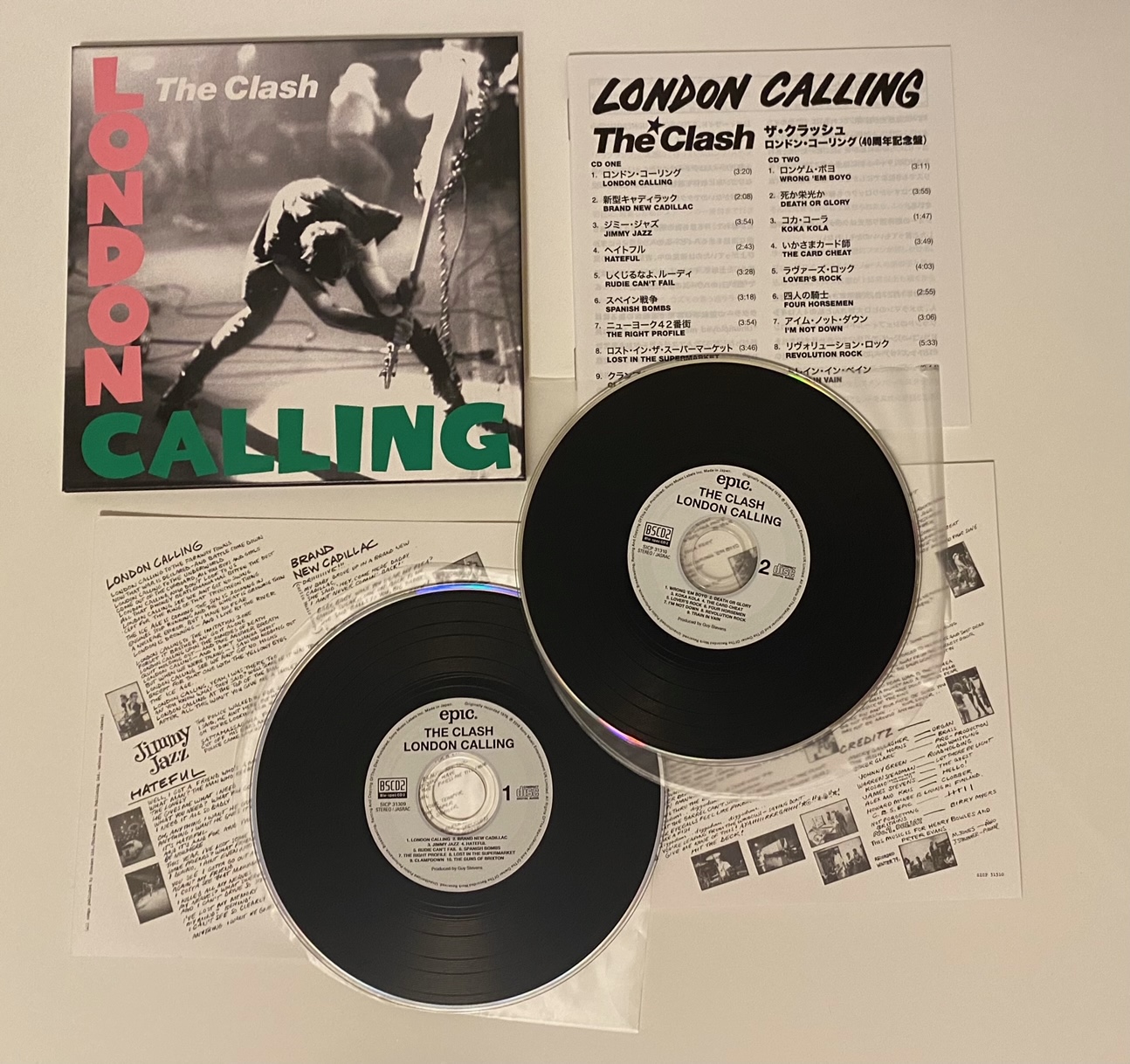

I then moved onto the 40th anniversary edition of The Clash’s London Calling, pressed on BSCD2 using the 2013 Tim Young remaster. The whole album fits onto one CD, but this edition replicates the original vinyl edition (except with “Train In Vain” listed on the back cover so not really the original original) and therefore spreads it out to two CDs designed to look like records. The exquisite mini-LP packaging includes scaled-down replicas of the original inner sleeves plus a booklet with Japanese notes and lyric translations.

How does it sound? I have the same 2013 remaster on the EU vinyl pressing (cut by original UK vinyl and 2013 digital mastering engineer Tim Young), which is well-balanced, three-dimensional, and lively. A good sounding record gets better as you improve your system; the 2013 vinyl passes the test, and while I haven’t heard the UK original, I’d estimate the 2013 gets you 85% of the way there. Much like the Pacific CD, the 40th anniversary London Calling Blu-spec played through my Arcam CDS50 immediately sounded sterile and dimensionally flat. Compared to the vinyl, there was a distinct lack of everything, which went beyond the usual vinyl versus CD comparisons. There was little sense of air or life. High frequencies sounded harsh and over-exaggerated, the hi-hats and cymbals trashy and fatiguing. The stereo rhythm guitars in the chorus of “Spanish Bombs” sound like natural, real guitars on the LP, but those transients became hard and ear-piercing on the CD. Horns on “The Right Profile” were strident, and the snare drum in that song’s intro didn’t have the subtle dynamic texture I was used to. Paul Simonon’s bass is certainly present on the Blu-spec but it doesn’t register as more than a blob of low-frequency information that sounds separated from the rest. Some of the vocals on London Calling are mixed rather low; you can make out the words on the vinyl, but it was harder on the CD. As it went on, the Blu-spec CD2 sounded less like The Clash and more like a jumble of sound desperately attempting (and failing) to resemble music. In general I heard a distinct lack of musicality and texture with an annoying emphasis on the top end. Like the Pacific CD, it sounded fake.

Maybe the vinyl rolled off the high frequencies, but whatever the case, it sounds infinitely better than the BSCD2. I ripped the BSCD2 and through the SSL 2+ compared it to the full resolution 96kHz/24bit files, and heard the exact same thing. CDs usually sound overly thick compared to their equivalent hi-res files, though the BSCD2 sounded thin. Hear for yourself with these excerpts from “The Guns Of Brixton" (hi-res file versus the Blu-spec):

"The Guns Of Brixton" BSCD2 comparison

What about the promised CD versus CD match? I bought the 2021 Blu-spec CD2 reissue of The White Stripes’ White Blood Cells (my favorite White Stripes album), and compared it to the 2008 Warner Bros./Third Man US CD. Both use the original digital mastering from 2001; I prefer the current all-analog vinyl but that’s another story. At first, the emphasized top end seemed to provide greater clarity, though it soon became fatiguing. Jack White’s voice sounded very thin, his guitar lacked the rich character that’s on the recording, and Meg’s drums sounded like cardboard. All the dimensionality that's on the master was gone. While the 2008 US CD sounded a bit grainy, it was much more organic and realistic than the plasticky BSCD2.

With any “new and improved” audio technology that Sony is even peripherally involved with, you can rely on a new Kind Of Blue to extoll the virtues of said new format. BSCD2 and the original BSCD were no exceptions, so I got the BSCD2 Kind Of Blue to compare with the 2000 SACD and the 1997 CD with Super Bit Mapping. The BSCD2 comes from the 2000 DSD master, though aside from resolution I’m not sure what the difference between the 1997 and 2000 versions are mastering-wise (Mark Wilder did both at Battery Studios). By itself, the Blu-spec CD2 gave an artificial impression of three-dimensionality, but sounded thin. Paul Chambers’ bass was sluggish and Jimmy Cobb’s cymbals sounded a bit metallic, though Bill Evans’ piano was fine and Cobb’s snare had decent texture. Yet Miles’ trumpet and Coltrane’s tenor sax sounded very artificial, and Cannonball Adderley’s alto sax was particularly strident on higher notes. Compared to the equivalent SACD and the similar 1997 CD, the BSCD2 sounded like someone went in and shoved isolation panels between all the musicians. Okay, that’s an exaggeration but the BSCD2 sucks the air, cohesion, and dynamic contrast out of the recording. If for any reason this is the only Kind Of Blue you’ve ever heard, the 1997 CD can be cheaply obtained and will blow your mind with how much better it is. Ditto the SACD if you have an SACD player. The Blu-spec doesn’t completely ruin Kind Of Blue, but only because it’s such an excellent recording to begin with.

I highly doubt that the last three I mentioned were re-EQ’d or otherwise messed with for the Japanese market; compare the measurements on those “The Guns Of Brixton” files and you’ll see that they measure very similar yet sound very different. However, a select few Blu-specs of Western albums feature Japan-exclusive mastering, such as the 2013 BSCD2 of the Stone Roses’ self-titled debut. That one is a Blu-spec repressing of a 2006 Japanese remaster; I haven’t heard the previous non-Blu-spec pressing, but I have no kind words about this BSCD2. It’s utterly terrible. Reni’s drums are dull, his hi-hats and cymbals thin, brittle, and painful to listen to. His kick drum and Mani’s bass are anemic. John Squire’s guitars have a grating lack of texture, and Ian Brown’s voice is recessed (but maybe that’s a good idea since he can’t sing). The Stone Roses Blu-spec is awfully bright, but worse than that is it doesn’t rock. This mastering destroys the groove that’s on the album, and when you suppress that, what’s the point? The mix has tons of artificial yet immersive reverb; here, it becomes an annoying glare cast over everything. The Roses sound like they’re playing in a tin can on a CD that’s glorified white noise. I also have an old American RCA/Silvertone CD (1184-2-JX) that’s thin and foggy and absolute garbage. The Blu-spec is better, solely because it might be salvageable if you rip it and re-EQ it. The transfer is certainly clearer, but that’s it. Like all the other Blu-specs I listened to, it just sounds wrong.

Conclusion

The abbreviation for Blu-spec CD2 is BSCD2. I think it should stand for BullShit CD2. It does make a perceptible difference, as variations in CD manufacturing often do. However, the BSCD2 difference is a consistently negative one. In their quest to sell more CDs and “improve” the format, Sony will only remind you of all the reasons you’ve hated CDs in the past. Maybe these are good if you have an overly sweet or warm DAC and these CDs balance that out, but for anyone whose digital setup is anywhere remotely near tonally neutral, stay away unless you want CDs that sound sterile and artificial.

I often think about Tracking Angle editor Michael Fremer’s review of Giles Martin’s recent stereo remix of The Beatles’ Revolver. “There remains a really and I mean really annoying quality to the images where a tambourine doesn't really sound like one but rather sounds like an apparition of one. Simple things like that tambourines or tom hits sound real on the original stereo mix. They just don't register as real on the remix… it sounds like a hologram.” The Blu-spec CDs had a very similar character of not sounding real, in a way that I wouldn’t attribute to aliasing issues or other things that often make CDs lackluster. All five that I listened to, no matter the source file or who mastered it, shared those same traits. Maybe you like that sound, but I really, really don’t; I think it hardly sounds like music. I will never again buy a BSCD2 unless it’s the only way I can physically own a recording, and even then I’d reconsider. The goal of the audiophile obsession is to get sound that’s good enough that you don’t have to think about how you got there. With the Blu-spec CD2, I found myself constantly thinking about all of those things you’re supposed to forget about. And it was $82 down the drain. Oh well, maybe those other Japanese CD formats will be better.

.png)