Nancy Harrow, Jaki Byard, Memphis Slim: Candid Records’ Reissue Campaign Does Justice To Its Original Run

IT’S FASCINATING THAT THIS LABEL EXISTED AT ALL — AND WE’RE REAPING THE BENEFITS IN 2025

Some of the most glorious moments in music history owe to a glitch in the mainframe — those fleeting, thrilling ruptures where the real shit breaks through. Case in point: Cadence Records, and its short-lived but seismic sister label, Candid Records.

From 1952 to 1964, Cadence mostly trafficked in vanilla fare — Andy Williams’ supper club ballads, the Everly Brothers’ clean-cut harmonies, the Chordettes trilling “Mr. Sandman” and “Lollipop.” There were outliers, sure: the unclassifiable pianist Don Shirley, who went on to inspire the film Green Book; guitarist Link Wray, by way of his galvanic single “Rumble.” But these were the exceptions that proved the rule.

In 1960, Cadence’s owner, Archie Bleyer flipped the script and launched Candid, a label devoted to bleeding-edge jazz. And he asked Nat Hentoff — a music critic, jazz fan, and civil libertarian, with scarce experience in the music industry — to be its A&R man.

Exactly why remains open for debate. (My colleague at Tracking Angle, Joseph W. Washek, compellingly theorized IRS avoidance.) Whatever the case, Candid’s modest roster — just over 30 albums across 18 months — contains a cross-section of some of the era’s most forward-thinking artistry, from Max Roach’s We Insist! to Cecil Taylor’s The World of Cecil Taylor to Abbey Lincoln’s Straight Ahead.

Fortunately, Candid has had a robust afterlife. In 1989, British producer Alan Bates (best known for his Black Lion record label) acquired the Candid name and revived the label, issuing hundreds of new titles — primarily a mix of reissues and new recordings, especially from UK and European artists. In 2021, the label entered a new chapter under Exceleration Music (owners of Mack Avenue, Alligator, Sundazed, Yep Roc, Kill Rock Stars et.al), which began reissuing its foundational catalog and signing contemporary jazz talent.

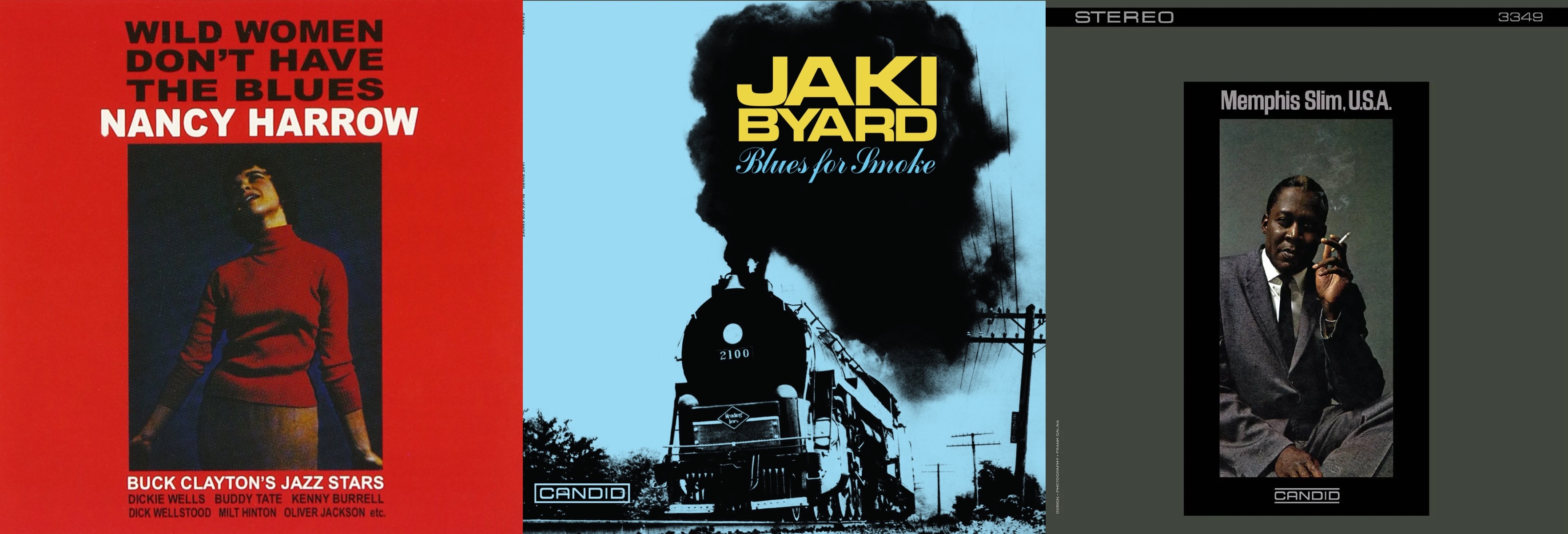

Last March, Candid announced a trio of 180-gram vinyl reissues from its original run — all from 1961 and occupying a distinct corner of the musical map: jazz-pop vocalist Nancy Harrow’s Wild Women Don’t Have the Blues; Mingus pianist Jaki Byard’s solo showcase Blues for Smoke; and bluesman Memphis Slim’s Memphis Slim, U.S.A.

So, how do they sound — on Tracking Angle editor Michael Fremer’s opulent system, where there’s nowhere for bad sonics to hide?

Music

Sound

Forget the lack of name recognition: jazz singer Nancy Harrow commands a fascinating legacy. She’s the mother of Damon Krukowski — drummer for downer-rock cult heroes Galaxie 500, one half of Damon & Naomi, and an incisive music writer. She was pregnant with him on the cover of her second album, 1963’s You Never Know, which notably shares a rhythm section with Van Morrison’s Astral Weeks: bassist Richard Davis and drummer Connie Kay.

Her 1961 debut, Wild Women Don’t Have the Blues, boasts similar firepower in its personnel: trumpeter Buck Clayton, trombonist Dickie Wells, tenor saxophonist Buddy Tate, baritone saxophonist Danny Bank, clarinetist and altoist Tommy Gwaltney, pianist Dick Wellstood, guitarist Kenny Burrell, bassist Milt Hinton, and drummer Oliver Jackson.

Together, they romp through eight spirited standards — from “On the Sunny Side of the Street” to “I’ve Got the World on a String.” While firmly rooted in its era, Harrow’s charismatic delivery — deeply influenced by Billie Holiday, as she’s acknowledged — and the top-shelf band around her help the record sidestep any stodginess.

“I thought it best to give her a bedrock, free-swinging background,” Nat Hentoff wrote in the original liner notes. “I knew she had the strength and beat not to be intimidated or muffled by a group of outspoken horns, and also felt she had the added vigor to spur them as well.”

This reissue captures that vigot in striking detail. The remaster by five-time Grammy winner Michael Graves is plush and defined; Jeff Powell sticks the landing with his vinyl master. Kenny Burrell’s solos in particular pierce through the bustling arrangements with vivid clarity.

“Having my oldest album become my newest album is pretty great,” Harrow, still creatively active at 94, told JazzTimes earlier this year. It’s heartening to see Wild Women Don’t Have the Blues get this kind of shine-up while Harrow is still here to enjoy it — and a fitting moment of justice for an undersung voice in vocal jazz.

Music

Sound

In his memoir, Notes From a Battered Grand, jazz pianist Don Asher recalled watching a teenage Jaki Byard tear it up at a dance. “It was jubilant, cocky, it leaped and shouted,” he wrote, “washed by echoes of all the music I had ever heard or read about — the Harlem house-rent parties, the strut of southland cakewalks and brass band parades, and endless, linked choruses of pile-driving boogie woogie that went lickety-split like a night train slamming across prairie tracks.”

Like the steam locomotive on its cover, Byard’s solo debut, Blues for Smoke, barrels ahead — moving through idea after brilliant idea with fluid invention. You can hear echoes of his musical upbringing — the gospel flourishes inherited from his mother, who played piano in church; the unmistakable imprint of Bud Powell’s bebop brilliance. And it’s all changed with a restless modernism that overlapped with pianists like Cecil Taylor — who, as Byard once claimed, used to come hear him play as a teenager.

Blues for Smoke also anticipates Byard’s later contributions to Charles Mingus’s ensembles — most notably on The Black Saint and the Sinner Lady and Mingus Mingus Mingus Mingus Mingus — as well as his sideman work with Eric Dolphy, including the equally revered Outward Bound and Far Cry. This unadorned album arguably presents Byard in his purest form — so it’s crucial to get the sound right.

Never fear when Bernie Grundman is in the credits: this is a rich sonic representation of Byard on that biting December day at Nola Penthouse Studios in Manhattan. Just because an album features one instrument doesn’t mean it can’t benefit from a great remaster: from fingers to keys and strings, Blues for Smoke sounds lush, distinct and well-articulated.

Music

Sound

Relaxed, loose, and companionable, Memphis Slim’s Memphis Slim U.S.A. feels less like a commercial product than an old friend — or three, really. Alongside vocalist/harmonicist Jazz Gillum and vocalist/guitarist Arbee Stidham, the blues singer, songwriter and pianist born John Len Chatman weaves rough-hewn beauty. The pitchy parts? Those are some of the best parts. This is real, raw acoustic blues by one of the finest to ever do it.

(Side note: if you’re a fan of Memphis Slim U.S.A., seek out Memphis Slim’s Tribute to Big Bill Broonzy, Leroy Carr, Cow Cow Davenport, Curtis Jones, Jazz Gillum — also released in 1961, and the product of the same sessions. An original pressing will do in a pinch — don't worry, we listened.)

It’s remarkable how badly Pure Pleasure Records whiffed it back in 2005. That pressing of Memphis Slim U.S.A. sounds thin and flat — like an early CD, but somehow worse. Fortunately, this new Candid edition is like Kansas giving way to Technicolor Oz: instead of detracting from the great bluesman, it brings out his depth and character.

Per Candid Records, these are the first true remasters of the Harrow, Byard, and Slim albums in half a century. (While Grundman cut Blues for Smoke from the original tape, the Harrow and Slim records are from digital files — which could have been out of necessity. Either way, the digital sources are so high-quality you need not sweat it.)

Where might they go from here? Booker Little? Phil Woods? Pee Wee Russell and Coleman Hawkins? Judging by the sound of these reissues, we can breathe easy. Job well done, Candid — then as now.

.png)