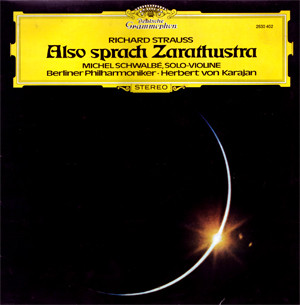

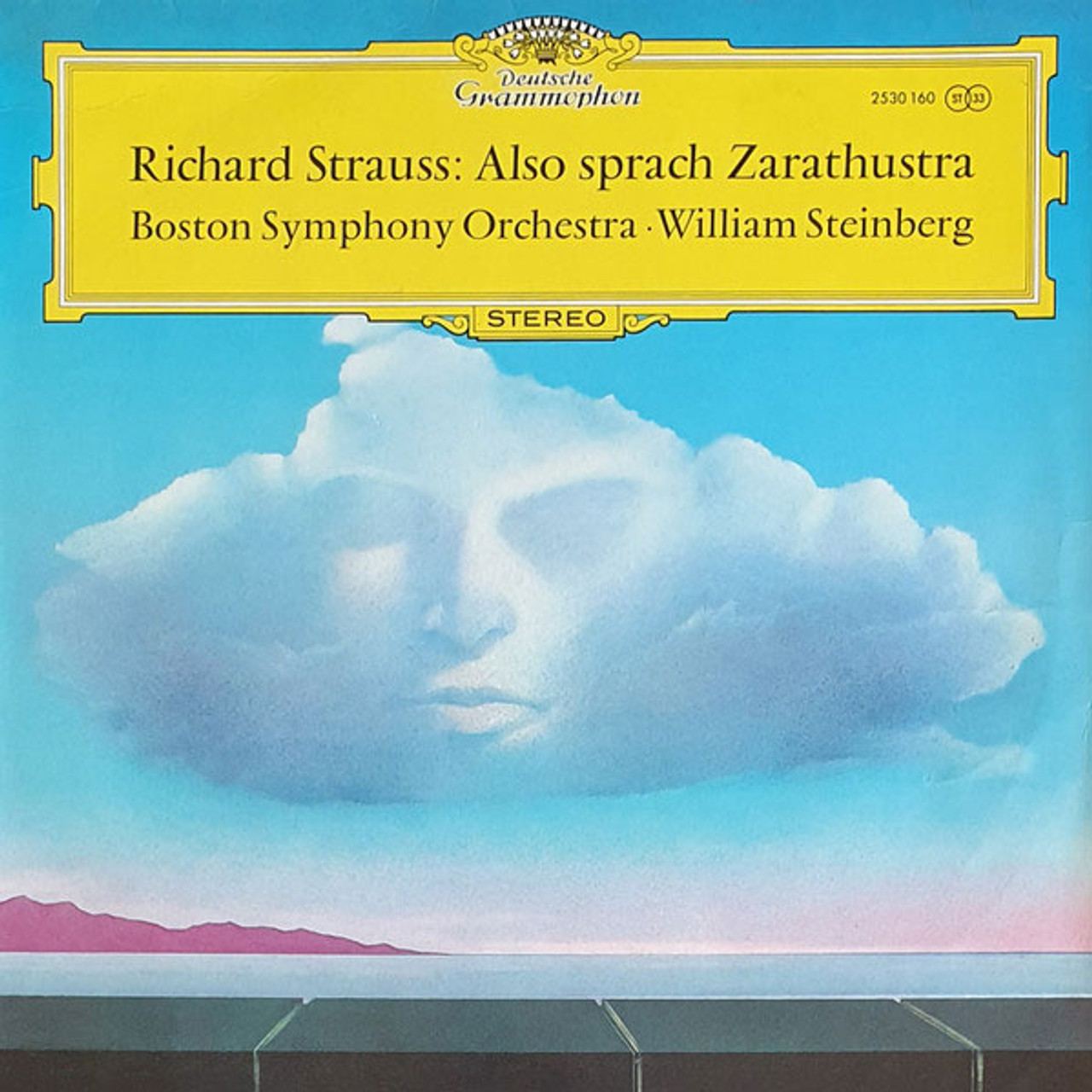

Classic Recordings by William Steinberg and the Boston Symphony Orchestra Are Reborn on Deutsche Grammophon’s Original Source Vinyl - PART 2: "Also Sprach Zarathustra" by Richard Strauss

Emil Berliner Studios Revitalize DG catalogue gems for a new generation of listeners

Richard Strauss

Richard Strauss

Richard Strauss: Also Sprach Zarathustra (Tone Poem for Large Orchestra, op. 30, after Nietzsche)

William Steinberg conducting the Boston Symphony Orchestra, with Joseph Silverstein (solo violin)

Production: Karl Faust/Tom Mowrey

Recording Supervision: Hans Weber

Recording Engineer: Günter Hermanns

Recorded 24th March, 1971 in Boston Symphony Hall

Reissue mixed by Rainer Maillard and cut by Sidney C. Meyer at Emil Berliner Studios

Music: 10

Sound: 9

Who has done more to boost sales of classical music recordings over the last 50-plus years than anyone else?

Stanley Kubrick - I would argue.

The director was famous for using all manner of classical music on his soundtracks, sometimes modified electronically, but always recognizable.

How many movie goers emerged from The Shining eager to explore Bartok’s Music for Strings, Percussion and Celeste or Penderecki’s Dream of Jacob and De Natura Sonoris No. 2, all featured prominently on the soundtrack? Or Rossini’s William Tell Overture and Beethoven’s 9th Symphony after watching A Clockwork Orange? Or Schubert’s Second Piano Trio so hauntingly used in Barry Lyndon? Hell, even Ligeti’s difficult but compelling piano music gets a thorough outing in Eyes Wide Shut…..

Well, Ground Zero for Kubrick’s rethinking of how to use classical music in films was 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968). No one who has seen that opening shot of a solar sunrise over the Earth in a theatre with a Big Screen and surround sound will ever forget the accompanying music: the opening “Sunrise” from Also Sprach Zarathustra. A solitary trumpet fanfare sounds out the elemental tonic-5th-octave phrase, followed by mighty orchestral chords. Then the timpani thumps out its tonic-dominant call to majesty before the sequence repeats. On the second repeat the whole thing goes several steps further, building into a massive final triumphant chord, joined by organ at full blast. It remains one of the most arresting combinations of music and image in cinema.

In Richard Strauss’s work, this music (that in 2001 reoccurs at crucial moments when Man is about to take a giant evolutionary leap forward), is merely the curtain-raiser to some 35 minutes of lush, late-Romanticism at its most fulsome (some would say decadent).

In retrospect, no other music could have caught the other-worldly majesty that Kubrick’s images demanded, and it seems unbelievable that at one time he thought other music could work. In the ultimately rejected score by Alex North the composer gives a more than passable imitation of Strauss, but in no way does it measure up to the simple, now iconic, grandeur of its model.

Before 2001, I’m not even sure that Strauss’s tone-poem was that well known. However, after the film came out, the work became one of those orchestral blockbusters that concert promoters love to program (guaranteed bums on seats) and classical labels love to record.

(Sidebar: That opening “Sunrise” became so popular it turned up on all manner of albums in new arrangements. Decca Phase 4 did a Moog-ey variant. It even got a fantastic jazz-funk reimagining by Deodato on “Prelude”, his 1973 album for Creed Taylor’s seriously cool label, CTI. Via Deodato’s version the “Sunrise” returned to the movies in Hal Ashby’s mid-career masterpiece, Being There (1979). It accompanied the perambulations of Peter Sellers’s Chance the Gardener, an idiot savant, as he wanders the mean streets of New York for the first time, marveling at just how bad things seem to be in comparison to his hitherto cloistered, idyllic life. This memorable sequence, because of its use of the Strauss and the allusion to 2001, cocks a real snook at Nietzshe’s notions of the übermensch and Kubrick’s speculations upon Man’s capacity to super-evolve).

Prior to the Steinberg/BSO recording under consideration, I believe the only version of the work released by Deutsche Grammophon was the somewhat lackluster 1958 recording by Karl Böhm. (Böhm was a noted Straussian, but his empathy for Strauss shines through less in his recordings of the tone poems, more in his recordings of the operas made for the Yellow Label and Decca). Owing to copyright issues, it is Böhm’s version of the opening “Sunrise” which is heard on the soundtrack album of 2001, whereas the version actually heard in the film is Herbert von Karajan’s 1959 recording with the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra, one of the classic early Deccas which I am most fortunate to own in an early wide-band pressing.

History of the Work

Also Sprach Zarathustra (1896), composed when Strauss was a young man, grew out of his interest in the philosophical writings of Nietzsche - an interest not unusual for young artists and intellectuals of the time. In a series of well-received earlier works composed in his 20s during the 1890s, Strauss had taken the new form of the so-called tone poem to a whole new level. The tone poem in his hands came to represent the ultimate expression of Romanticism in music next to opera (the art form in which Wagner had pushed tonality to the breaking point in Tristan und Isolde). The classical formal procedures of the symphony, which dated back to Haydn, seemed incompatible with the emotional and harmonic turmoil embodied in the music of the late Romantics like Strauss. The tone poem, whose origins lay in the pictorial, storytelling (and extra-musical) elements of works like Beethoven’s Pastoral Symphony, and Berlioz’s Symphonie Fantastique, had been further developed into freestanding works by that avatar of über-Romanticism, Franz Liszt. Works like Mazeppa (1838 - 1854), Tasso: Lamento e Trionfo 1840 - 1854), Les Préludes (1845 -1854) led the way for Smetana (Ma Vlast - My Fatherland), Dvorak (The Golden Spinning Wheel, The Noon Witch), and Sibelius (Finlandia, The Swan of Tuonela). But it was Richard Strauss who ran with the form, creating vast structures of the same length and scale as the grandest of symphonies.

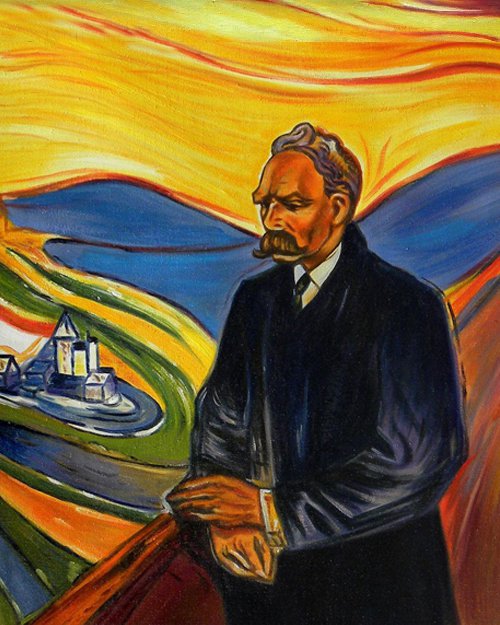

Also Sprach Zarathustra is essentially a series of episodes strung together, each one inspired by the philosophical writings of Nietzche contained within his book of the same title. Nietzsche was a writer with some pretty grandiose ideas about the place of Man within the scheme of things. Even before writing Zarathustra, he had declared: “God is dead. God remains dead. And we have killed him. How shall we comfort ourselves, the murderers of all murderers?”

Nietzche by Edvard Munch (1906)

Nietzche by Edvard Munch (1906)

Richard Strauss, who also had some pretty grandiose ideas of his own, was the perfect composer to embark on what was, if you think about it, a pretty daring task: to represent in music Nietzsche’s depiction of a prophet-like figure, Zarathustra, who proceeds to make various pronouncements about the death of God and the coming übermensch (sometimes translated as “Superman”), amongst other minor matters. But you really do not need to know what the book and tone poem episodes describe to fully enjoy the music.

Nietzsche’s notion that Man had superseded God, and would struggle to maintain moral equilibrium as a result, found its perfect reflection in the crisis of tonality that presented itself to Strauss and his contemporaries - the post-Wagner generation. This crisis had afflicted Western classical music since Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde (first performed in 1865) spent some 4 hours engaged in musical coitus interruptus to reflect its tale of doomed lovers. The entire fabric of the classical tradition over hundreds of years had been built upon the idea of concord moving to discord and back to concord. In Tristan those lovers try in vain to consummate their love, while the music, spinning an endless web of chromaticism to prevent resolution, refuses to return to any kind of home key until the very end of the opera. With Tristan lying dead before her, Isolde expires from a broken heart and a willing embrace of “love in death” (the culminating Liebestod). Only then do we get our long-delayed musical orgasm as the orchestra finally returns to a home key and concord.

Hell of a way to go.

The Liebestod from Tristan und Isolde: a production at Longborough Festival Opera which deliberately calls back to scenic elements of earlier classic productions (here recalling Wieland Wagner's post-War version at Bayreuth)

The Liebestod from Tristan und Isolde: a production at Longborough Festival Opera which deliberately calls back to scenic elements of earlier classic productions (here recalling Wieland Wagner's post-War version at Bayreuth)

In the wake of Wagner’s provocations, his dare to dismantle tonality, composers indulged in ever more effulgent chromaticism, a trend which culminated in the notion that there is no such thing as concord and discord: all chords and notes are created equal. This in turn led to atonality and ultimately the discarding of tonal systems completely in the serialist method proposed by Arnold Schoenberg in the early 1920s.

Arnold Schoenberg by Oskar Kokoschka (1924)

Arnold Schoenberg by Oskar Kokoschka (1924)

Schoenberg started out writing music that sounded a lot like Strauss: highly chromatic, sensual and sexual (eg. Verklärte Nacht). But the difference between where the two composers went from there came down to the fact that Strauss was fundamentally a traditionalist who wanted to make money from his art; he was not a revolutionary like Schoenberg who was also pre-occupied with compositional theory.

For Strauss, that opulent chromaticism within which his music luxuriates, was merely the new normal. In his early tone poems, he relished the extra frisson imparted by his embrace of tonal fluidity. And in the score for Also Sprach Zarathustra he pulled out all the stops. The closest he got to actually overthrowing tradition was in his opera Elektra (1909), whose premiere scandalized Europe as much because of its salacious content as its almost violent assault on the way music was supposed to sound. Elektra pre-echoes the Palace coup of Stravinsky’s Le Sacre du Printemps (The Rite of Spring), only four short years later.

Strauss’s awareness that he was writing music within a new space of exploration but also instability, of looking forward as much as back, was reflected in his original subtitle for Zarathustra (later removed): “Symphonic Optimism in fin de siècle form, dedicated to the 20th Century”.

You can hear the dichotomy between the old (stability) and the new (instability) presented within the first minutes of the work. First you have that opening “Sunrise” with the trumpet fanfares outlining that most fundamental of all diatonic chords - C major - in as straightforward a manner as you can imagine: C - G - C. But when the rest of the orchestra enters, and dramatically drops by a semi-tone the major third of the C major chord - E - to E flat, there is an immediate sense of destabilization. Then the edifice rights itself with a repeat of that C major fanfare. At the end of the “Sunrise”, C major is unequivocally reaffirmed in the massive climax.

However, immediately Strauss subverts all of this tonal assertion within the next movements. Tonally unsettled half-gestures eventually move into as ravishing a chromatic paean to desire as you are ever likely to hear. It’s like diving into a lake of melted chocolate and whipped cream!

And so it goes through the rest of the piece, in which Strauss revels in his mastery of complex, fin-de siècle chromatic harmony and rich orchestration. The work is a masterpiece of late-Romanticism in all its decadent glory, but it never slips into territory that might be more threatening to the status quo. Underneath all that reveling in the freedom afforded by Wagner’s loosening of the harmonic rules, beats the heart of a traditionalist.

Later on, after Strauss retreated from the excesses of his operas Salome and Elektra, he largely eschewed purely orchestral composition (with the major exception of the Alpine Symphony of 1915), concentrating instead on writing operas. There he found the perfect balance (for him) between formality and indulgence, frequently tipping a hat to those who had gone before him. The result was that an opera like Der Rosenkavalier could very well have been written by Mozart were it not for the added spice of the composer’s chromatic wanderings.

Richard Strauss

Richard Strauss

Performing and Recording Also Sprach Zarathustra

One of the reasons I have gone into all this detail of where Strauss’s music sits within what was going on in classical music of the time, is because any conductor who decides to tackle a work like Also Sprach Zarathustra has to decide where he (or she) stands in terms of just how objectively - or subjectively - they approach the score.

Will their performance run hot or cold or somewhere in the middle?

Strauss’s idiom is such that it is easy to lose yourself in the sheer lush excess of it all. Or you can stand back a bit, letting the music’s indulgences speak for themselves without any extra encouragement.

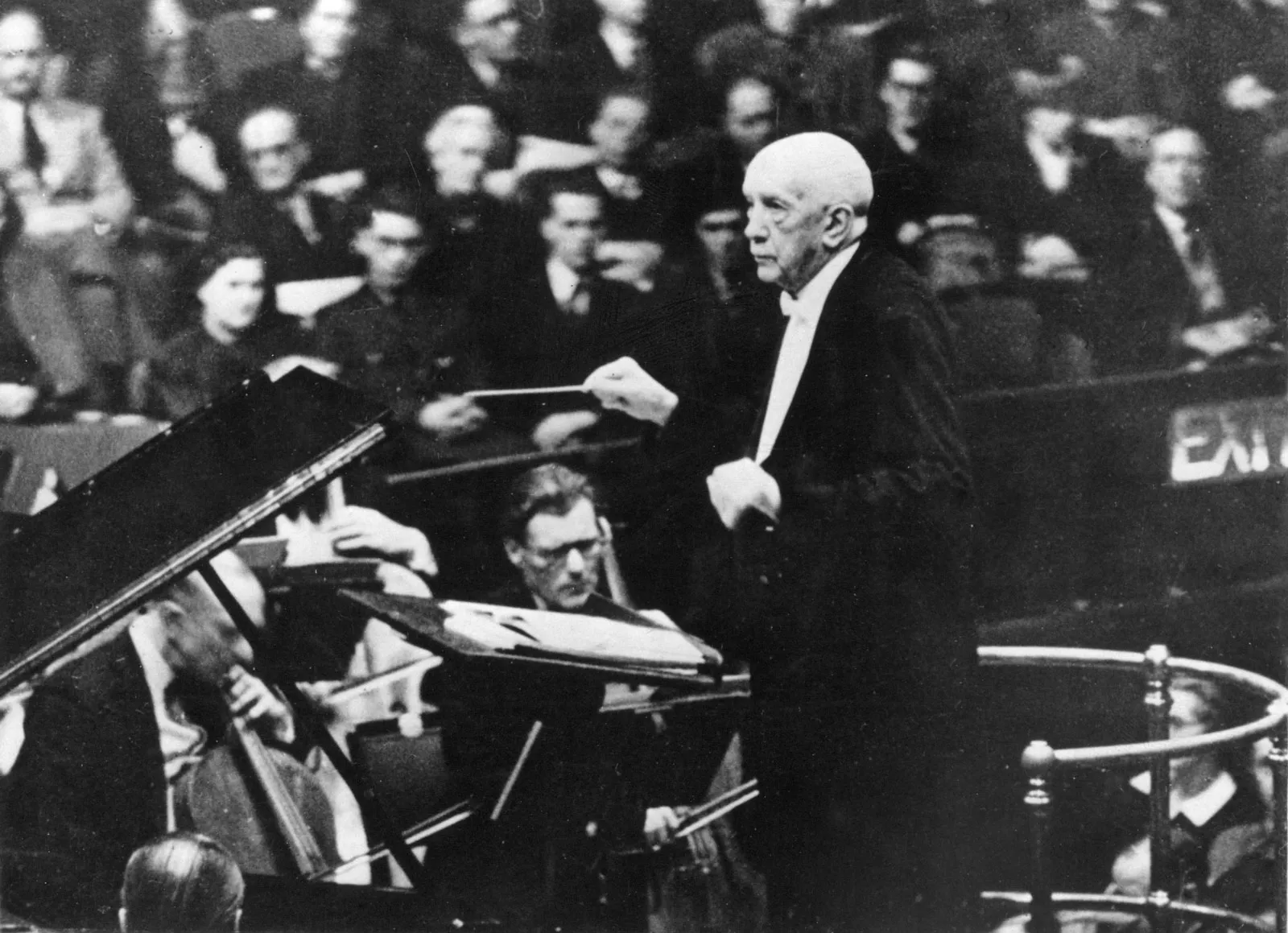

Herbert von Karajan, an acknowledged Straussian of the first order, inclines towards the more indulgent approach, and each of his three Zarathustra recordings demonstrate his mastery of the idiom. However, his middle one for DG from 1973, is the recording which - for many - is the non pareil.

It is a masterclass in Strauss conducting, with the Berlin Philharmonic dipping and swooning to extravagant degree, in perfect sync with their conductor. Karajan’s version of the section that comes after the “Sunrise” fairly drips with over-the-top sentiment. You swear you could have a heart attack merely by listening to it. Too much of a good thing? Absolutely not.

It is a masterclass in Strauss conducting, with the Berlin Philharmonic dipping and swooning to extravagant degree, in perfect sync with their conductor. Karajan’s version of the section that comes after the “Sunrise” fairly drips with over-the-top sentiment. You swear you could have a heart attack merely by listening to it. Too much of a good thing? Absolutely not.

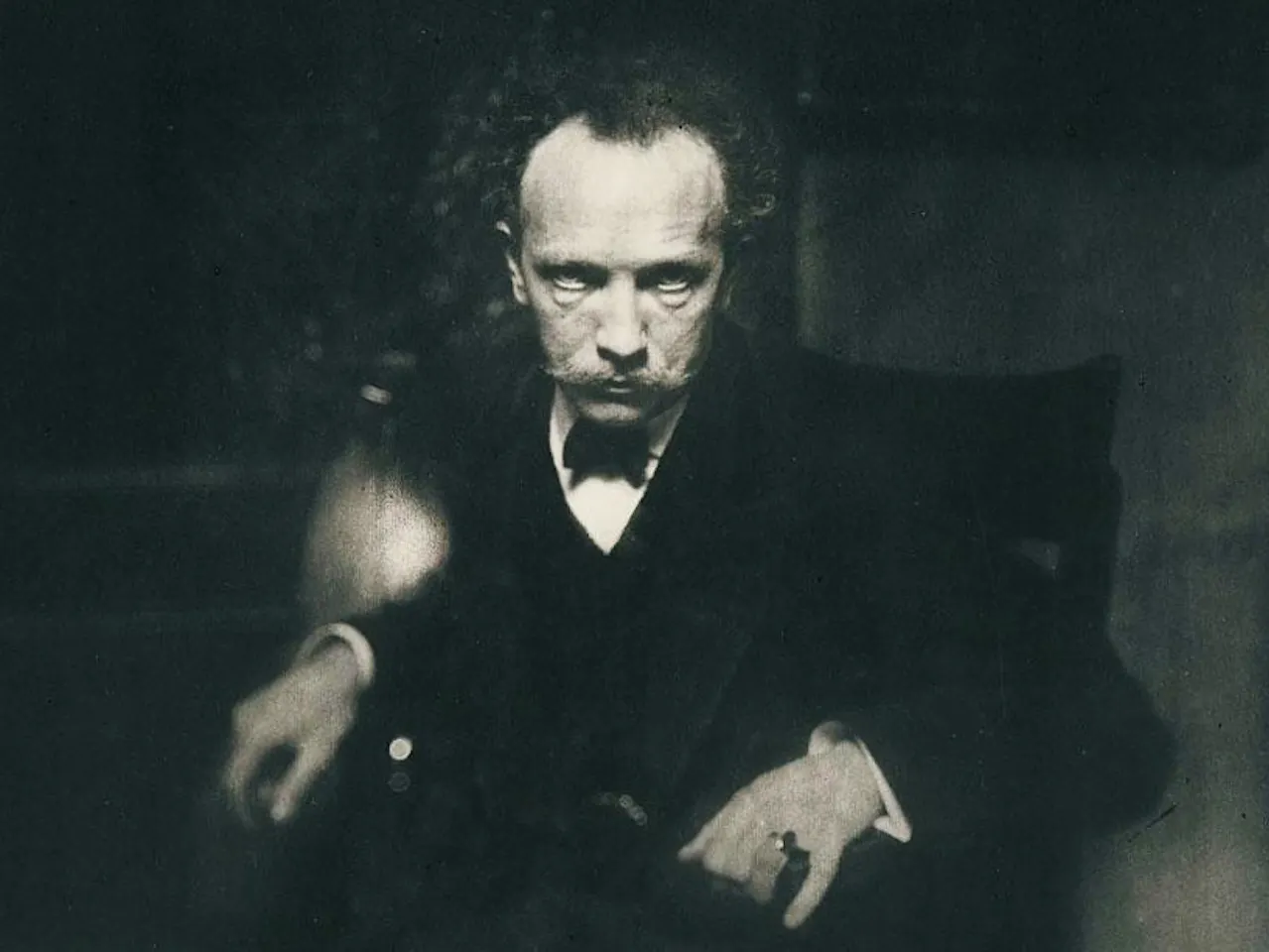

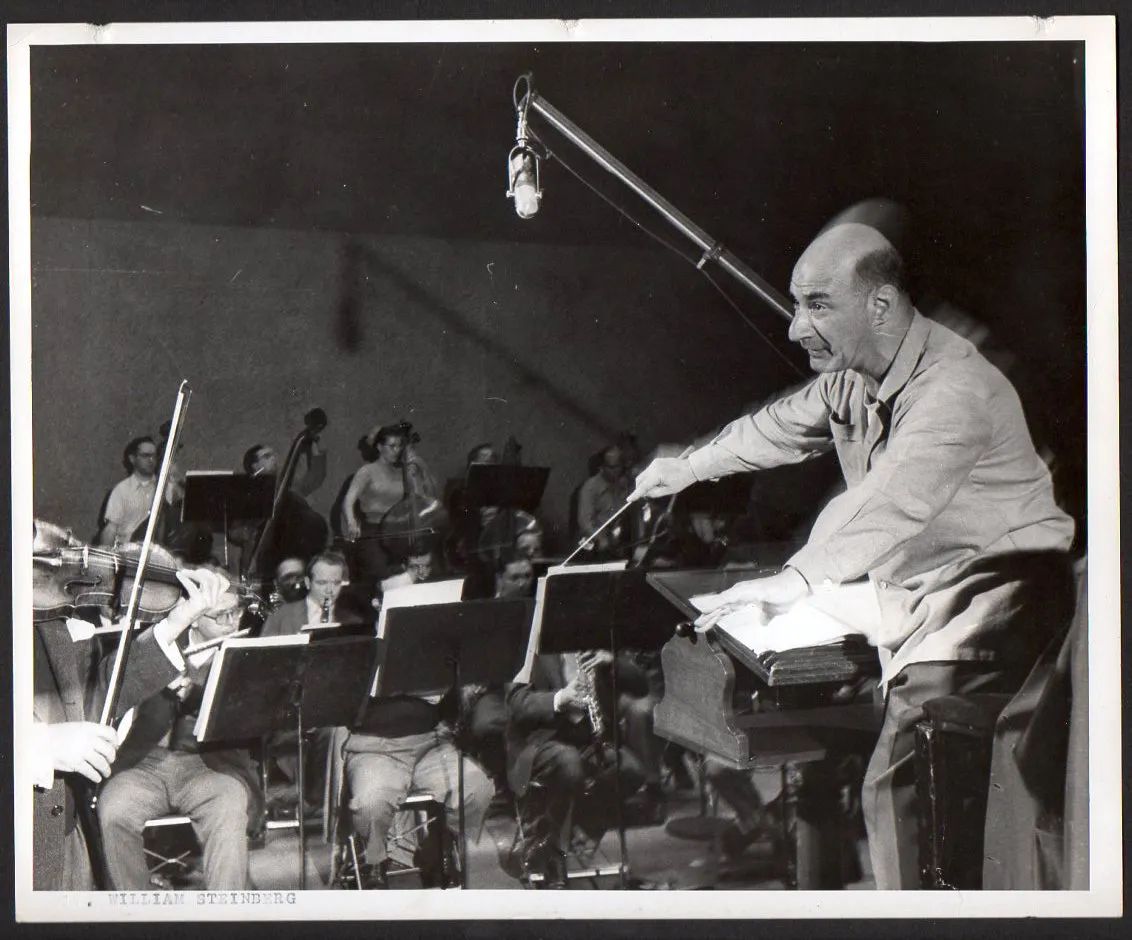

William Steinberg (recording with the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra)

William Steinberg (recording with the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra)

By comparison, Steinberg is definitely coming from a more objective place, and listening to him in this section after Karajan can feel a little underwhelming.

But that’s not to say Steinberg’s approach doesn’t work, and in fact for many it will be a breath of fresh air. He is a sure and steady guide, and the orchestra plays its heart out for him. Strauss’s tone poems get performed and recorded a lot, and in the wrong, over-indulgent hands they can really wear out their welcome pretty quickly.

Steinberg and the DG engineers set their cards out on the table from the get-go, with a bracing opening “Sunrise”. When the timpanist entered I nearly jumped out of my seat, it is so arresting. You’d be amazed how often this gets screwed up on recordings. You sometimes can’t believe conductors and engineers settled for what is on the tape.

In each successive episode, the BSO on top form revels in its easy virtuosity. Steinberg was a great trainer of orchestras, as Toscanini recognized, and it shows. Those warm woodwind textures, the bright burnished brass (just listen to those swooping horns and those fat tubas making your woofers tremble), the sweet-sounding strings: all are marshaled by Steinberg in a reading that never seems to be working too hard to bring out the inner life of the music - it’s just naturally there. With many recordings of Zarathustra it is quite the opposite: you feel the labour involved. Steinberg keeps things moving, but never short changes the music’s richness. This is the perfect recording for those who do not always relate to this music or Strauss’s idiom in general.

One of the highlights is the “Tanzlied” episode, led by the solo violin, in this case the legendary concertmaster of the BSO, Joseph Silverstein.

Joseph Silverstein

Joseph Silverstein

His silken tones lead on the dance like a veritable Pied Piper. The results are joyful and exhilarating. The climax, when it comes, is massive and fully accommodated - bell and all - without any sense of strain by the DG engineers, .

Steinberg doesn’t dwell on the final “Das Nachtwandlerlied” (The Night Wanderer’s Song). Rather he leads us gently through the wind-down of the piece, letting the orchestra die away to the final enigmatic conclusion, where woodwind chords in one key alternate with pianissimo plucked bass notes in another, barely audible but still present on this immaculately cut and pressed reissue.

The sound throughout is effortless and transparent, capturing a great orchestra and conductor in complete symbiosis. As with The Planets there are times when I feel the room reverberation is a touch excessive, so that I am hearing that reverberation more than the direct sound of the orchestra. It’s not an artificial sound by any means - I think it is merely a consequence of where the orchestra was seated in the hall and how it was miked. (For a more detailed discussion of this, I refer you to my discussion of this issue in my earlier review of The Planets). Some of you may be less troubled by this than I am. Reluctantly, this is why in my ratings I have deducted one point for the sound.

Other Recordings

The 1973 Karajan version on DG is similarly afflicted by a large acoustic, in his case the Jesus-Christus-Kirche. There is that characteristic, slightly glassy quality to the sound (strings especially) that we’ve come to expect from DG recordings made in that space in this era. Nevertheless I still think this is an essential purchase for any Strauss lover, and the vinyl reissue by Speaker’s Corner from a few years back is the version to get. Karajan’s earlier recording with the Vienna Philharmonic on Decca (the one used in 2001) is less polished, but will be essential for any Decca-holics like myself.

Beyond that, probably the most spectacular version sonically (next to the Steinberg) is Georg Solti’s 1976 account with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, recorded by the great Kenneth Wilkinson for Decca. For some unaccountable reason the original release contained Zarathustra on one side of the record instead of split across two, thoroughly compromising the sonics, so this version is not an option. Seek out the rare King Super Analogue vinyl reissue - it’s worth it.

Beyond that, probably the most spectacular version sonically (next to the Steinberg) is Georg Solti’s 1976 account with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, recorded by the great Kenneth Wilkinson for Decca. For some unaccountable reason the original release contained Zarathustra on one side of the record instead of split across two, thoroughly compromising the sonics, so this version is not an option. Seek out the rare King Super Analogue vinyl reissue - it’s worth it.

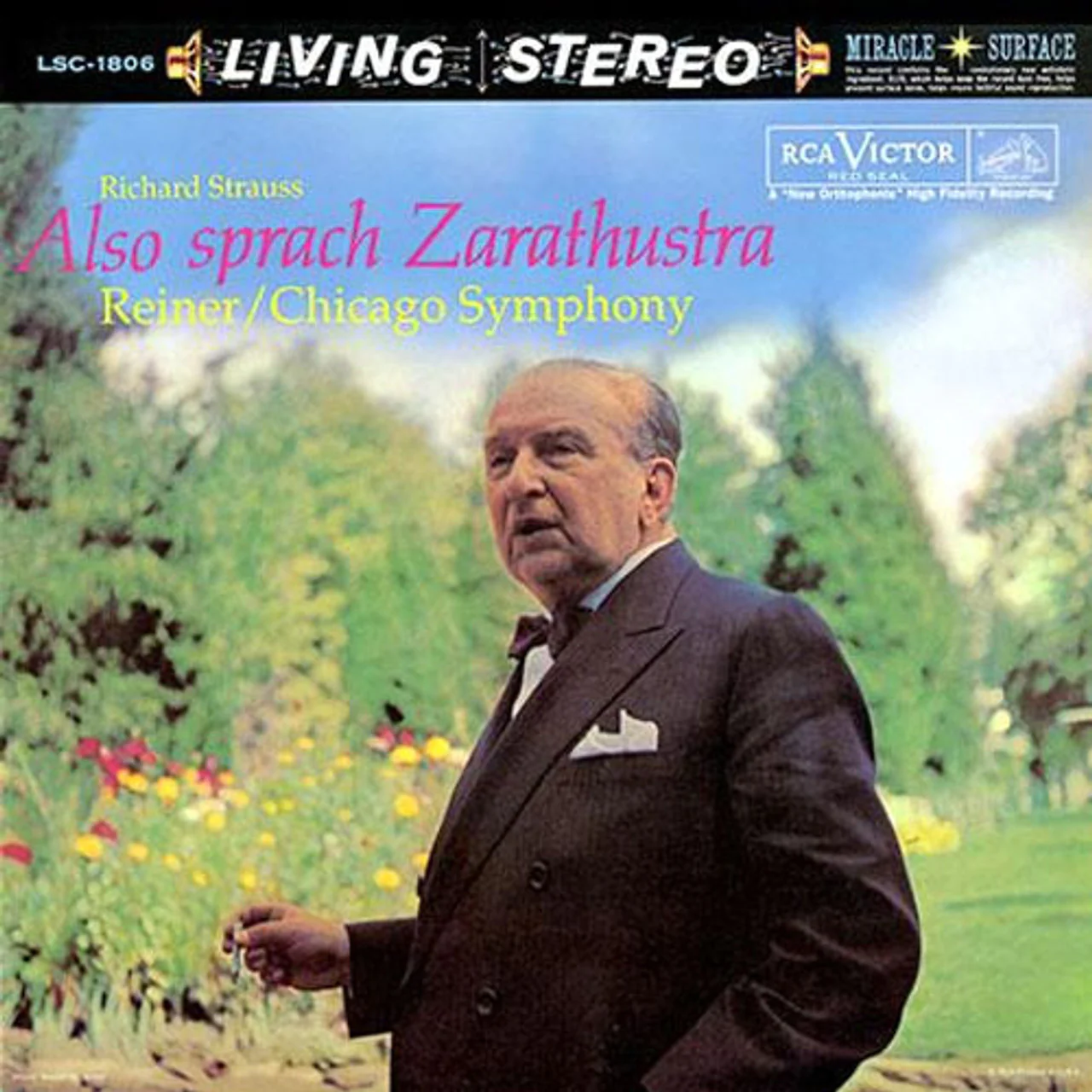

The other audiophile classic (and another benchmark) is Fritz Reiner’s immaculately schooled account with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra on RCA Living Stereo.

The other audiophile classic (and another benchmark) is Fritz Reiner’s immaculately schooled account with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra on RCA Living Stereo.

Incredibly this was recorded in 1954, although the stereo release did not get issued until some years later. The currently in-print version from Analogue Productions is better than the early Classic 33. I must say this was never one of my favorites, despite the excellent playing and recording. It’s a little bit too business-like for my taste: I guess I’m just an unabashed schlagsahn kind of guy when it comes to Strauss.

Incredibly this was recorded in 1954, although the stereo release did not get issued until some years later. The currently in-print version from Analogue Productions is better than the early Classic 33. I must say this was never one of my favorites, despite the excellent playing and recording. It’s a little bit too business-like for my taste: I guess I’m just an unabashed schlagsahn kind of guy when it comes to Strauss.

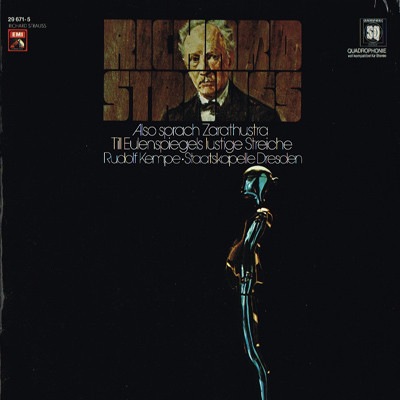

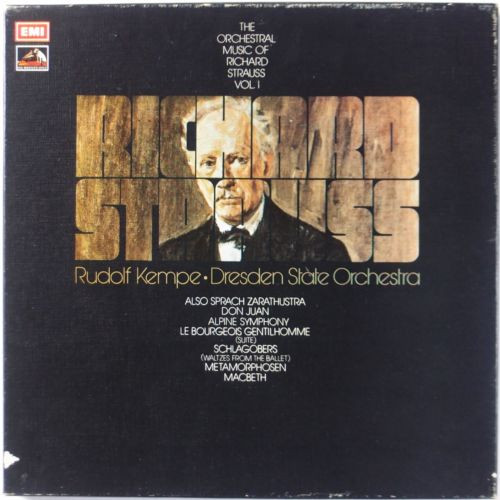

Not in the same league sonically, but nevertheless essential for Straussians, will be Rudolf Kempe’s 1973 account with the Dresden Staatskapelle for EMI (coupled with Till Eulenspiegel).

Dresden maintained a relationship with the composer’s music across 60 years and two world wars, with many premieres taking place there. During his life and beyond, the Staatskapelle (which also played in the opera house) enjoyed (and enjoys) universally acknowledged authority in both his orchestral works and operas. The orchestra has a strong spiritual and sonic connection to Strauss’s music. Do yourself a favor and pick this up in one of the box sets dedicated to all of Strauss’s orchestral works as recorded by these artists: Zarathustra is in Volume 1. Go for either the British postage stamp EMI set or the German EMI Electrola box.

Dresden maintained a relationship with the composer’s music across 60 years and two world wars, with many premieres taking place there. During his life and beyond, the Staatskapelle (which also played in the opera house) enjoyed (and enjoys) universally acknowledged authority in both his orchestral works and operas. The orchestra has a strong spiritual and sonic connection to Strauss’s music. Do yourself a favor and pick this up in one of the box sets dedicated to all of Strauss’s orchestral works as recorded by these artists: Zarathustra is in Volume 1. Go for either the British postage stamp EMI set or the German EMI Electrola box.

.png)