Emil Berliner Swings For the Fences With Another Batch of "Original Source" Titles

Will their bold play pay off?

When the new batch of Deutsche Grammophon Original Source records arrived from the label for review, fellow Tracking Angle writer Mark Ward alerted me that I was on deck. And while I can’t hope to match his tour deforce review outlining the first four titles in this series, I have been eager to put into words my thoughts on the ongoing results of this monumental undertaking.

While I didn’t formally review the first four titles, I did listen to all of them, and they truly impressed me, unleashing levels of detail, dynamics, and soundstage I had never heard in a Deutsche Grammophon recording, regardless of era. These titles are of course pulled from the label’s catalog of quadrophonic four-track recordings produced in the early 70s, remixed directly from the four-track masters using a custom mixing desk to accommodate the wide half-inch tape and proprietary-built preview head. If you want a deep dive into the mixing and cutting process for this series check out Mark’s original review and also the video produced by EBS below:

This second batch of titles covers some core romantic repertoire, including some notoriously difficult to cut works such as the Brahms piano concertos (for reasons of length) and the Verdi Requiem (for ensemble size and dynamics). These works, including the third release featuring Debussy’s "Nocturnes" and Daphnis and Chloe suite, are commonly recorded war horses with numerous vinyl versions available in audiophile pressings from the likes of Decca, EMI, Mercury, and RCA. The question of artistic quality was never a weak point for Deutsche Grammophon, which is why this original source series is important, now we get to see how well these noteworthy performances can compete with the usual collector go-to’s of audiophile pressings.

First up is Verdi’s Messa da Requiem led by DG’s house pairing of Herbert von Karajan and the Berlin Philharmonic.

Giuseppe Verdi: Messa Da Requiem

Giuseppe Verdi: Messa Da Requiem

Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra and Vienna Singverein conducted by Herbert von Karajan

Mirella Freni, Soprano, Christa Ludwig, Alto, Carlo Cossutta, Tenor, Nicolai Ghiaurov, Bass

Recording: Berlin, Jesus-Christus Kirche, January 1972

Executive Producer: Dr. Hans Hirsch

Producer: Hans Weber

Balance Engineer (Tonmeister): Günter Hermanns

Remixing: Rainer Maillard

Cutting: Sidney C. Meyer

Limited Edition of 2000

Italian opera composer Giuseppe Verdi (1813-1901) wrote his Requiem in late 1873 after toying with material for it for roughly 5 years. He first was inspired to write a Latin requiem mass after the death of fellow Italian composer Gioachino Rossini in 1868. Verdi submitted one movement, the “Libera me” to be performed together with movements from other leading Italian composers in a concert dedicated to Rossini’s honor. However, this performance was canceled a week before the scheduled premier and the Messa per Rossini never saw a staging in Verdi’s lifetime.

Giuseppe Verdi

Giuseppe Verdi

In 1873, another leading Italian cultural figure, writer and philosopher Alessandro Manzoni passed away. Manzoni was a hugely influential figure for Verdi and for Italian culture in general, as he helped to stabilize the modern Italian language, as well as push for a unified secular Italian state. Manzoni’s death inspired the composer to revise his previous “Libera me” and complete a full requiem in the writer’s honor. The finished Messa da Requiem was performed in Milan on May 22 1874, the one-year anniversary of Manzoni’s death, to immediate success and acclaim.

Alessandro Manzoni, the dedicatee of Verdi's Requiem

Alessandro Manzoni, the dedicatee of Verdi's Requiem

The Requiem is a massive work, scored for full orchestra, an additional four offstage trumpets, double choir, and four operatic soloists. The double choir makes this work difficult to stage in traditional concert halls and is most often performed in opera theaters and large cathedrals. As a student I performed the requiem at the sprawling cathedral of St John the Divine in New York and can attest to the numerous challenges of directing such a large ensemble of musicians, and by extension, capturing such a performance on a recording. There are a number of competitive recordings of the Requiem on vinyl. The first major stereo version was recorded in 1960 by Fritz Reiner and the Vienna Philharmonic with the fabled “Decca team” contracted by RCA in Europe during that period. It can be found in both the original 1961 Living Stereo Soria pressing, as well as a later reissue on UK Decca. It is thunderous but not particularly detailed account with excellent ambiance and an all-star cast that includes soprano Leontyne Price. There are also excellent readings from Carlo Maria Giulini on EMI, as well as from Georg Solti also on Decca, the latter of which features one of the best casts of vocal soloists ever assembled with the likes of Joan Sutherland, Marilyn Horne, Luciano Pavarotti, and Martti Talvela.

There are a number of competitive recordings of the Requiem on vinyl. The first major stereo version was recorded in 1960 by Fritz Reiner and the Vienna Philharmonic with the fabled “Decca team” contracted by RCA in Europe during that period. It can be found in both the original 1961 Living Stereo Soria pressing, as well as a later reissue on UK Decca. It is thunderous but not particularly detailed account with excellent ambiance and an all-star cast that includes soprano Leontyne Price. There are also excellent readings from Carlo Maria Giulini on EMI, as well as from Georg Solti also on Decca, the latter of which features one of the best casts of vocal soloists ever assembled with the likes of Joan Sutherland, Marilyn Horne, Luciano Pavarotti, and Martti Talvela.

Karajan’s 1972 account has stiff competition, and while it’s never been considered one of the most revered performances of the work, it certainly received a good share of accolades and admiration over the years. One factor helping it is the soloistic talent of mezzo-soprano Christa Ludwig, and Bulgarian bass virtuoso Nicolai Ghiaurov. This particular Requiem, like many of Karajan’s 1970s Berlin recordings, was captured in the city’s Jesus-Christus-Kirche. Since I never owned an original copy of this recording, Mark was kind enough to loan me his 1972 German pressing so that I could properly compare this new version mastered by Rainer Maillard and cut by Sidney Meyer.

The Requiem was one of Karajan’s signature pieces over the years, he recorded it a handful of times, and it was the final piece he conducted with the Berlin Philharmonic before his death in 1989. Karajan certainly has a command of the repertoire here, although at times his tempos are a bit slow and plodding. While the playing of the Berlin Philharmonic is as fine as always, they are somewhat relegated to the background in both this piece and this recording, and the real stars of the show are the operatic soloists. This is a stellar cast with the only weak link being a rather unsure performance from tenor Carlo Cossutta. Christa Ludwig and Mirella Freni soar in their respective roles, while the powerful voice of Nicolai Ghiaurov is so confident and assertive that you’d think he was directing the orchestra himself. Would this be my first performance of this piece to grab if I could only have one? Sadly, no, for that I would recommend either the Giulini or the Solti, but the thing about classical music is that you don’t have to have just one recording per piece, half the fun is in collecting different interpretation!

The original DG “ring” pressing was not very pleasing to listen to, in fact before he loaned me his copy, Mark remarked “You’ll want to put it on for about 5 minutes and then immediately take it off.” It’s a wonder that this recording received positive attention at the time with the sound quality it had, but we have to remember playback systems have improved dramatically over the years, and these differences might not have been noticeable to the average consumer. Sound on this record was murky, voices were shaded, and the tonal balance was focused almost entirely in the upper midrange.

The EBS-cut Original Source pressing was a dramatic reimagining, from the first string notes and entrance of the choir, everything is much more sharply defined. The biggest difference in overall presentation is how wide the orchestral stage got. This is going to be a reoccurring theme throughout this review because I think it is the area where Maillard and Meyer were able to accomplish the most improvement. With this large expansive soundstage, comes detail and space around the instruments. Many original DG pressings sound incredibly congested and nasal, there is a relieving openness here.

Talking about the balance is a little more difficult. The requiem is a very difficult work to record in a number of ways. The size of the ensemble makes balance difficult to gauge, and the dynamics of the piece from the subtle choir and string passages to the brass-heavy Dies Irae themes, requires difficult mastering and cutting decisions. Both the original pressing and this new cut put an incredible focus on the soloists. Now, that’s not necessarily a bad thing, because the cast is so exceptional here, but if you’ve seen this work performed live, you’re going to notice that the balance sounds a bit strange. These operatic soloists certainly have the chops to fill the hall, but no opera singer in the world can out-compete an ensemble of the size presented here, but that’s exactly the perspective engineered on this record.

Mezzo Soprano Christa Ludwig

Mezzo Soprano Christa Ludwig

One issue with this particular recording that I encountered, was simply a lack of bass. Now let me explain: Obviously bass is lacking on the original pressing, as is the case for most DG pressings of the time. But the issue is not limited to pressing, I suspect because the recording venue of so many of these 70s Karajan recordings, the Jesus-Christus Kirche in Berlin, lacks bass in its hall acoustic. Emil Berliner clearly did a lot to bring out what bass there was on the tapes, and in certain places they succeeded. This is notable in the quiet, subtle orchestral passages where you can really hear the extension of the cellos and double basses. However, this extension does not last into the fortissimo passages, and it results in tutti passages that sound bright and glassy. The Dies Irae is a tricky passage to put on record, but the bass drum hits on this pressing simply sound anemic, and the sound of the orchestra is just not full, rather it is very top heavy and this is simply not what an orchestra sounds like live. By comparison, both my Reiner/Decca pressing, and my Solti/Decca pressing had much deeper, more impactful bass in these passages, with the Solti narrow-band London/Decca pressing having the best sound overall. If you don’t believe me, grab yourself a copy to compare, they can easily be had for $5-15.

I think this is an excellent pressing of this notable recording, but in the pantheon of good sounding, good performances of the Verdi Requiem, I simply think you can do better. If you are an operatic vocal fan, this is an excellent example of a great solo cast, and the remastering work of EBS has made their singing really shine, with excellent texture and dynamics. It’s just that the large full-ensemble passages have problems that cannot be overcome, leading to a somewhat bright experience. I think in terms of performance, the Solti, the Reiner, and the Giulini are all superior, and that’s not a huge surprise, as those performances tend to top lists of the greatest versions of this piece, while the Karajan does not usually get a mention. In terms of sound, they all have ups and downs, as it’s such a difficult piece to record. Personally, I would rank the Solti as the best sounding (and the best performance), while the Reiner and Karajan were more or less equal with the Reiner being much better in string tone and bass, while the Karajan succeeds in vocal texture, soundstage, and detail. The Giulini is a fantastic performance, but the sound is a bit more muddy than the others mentioned, and the perspective is much further back in the hall.

This is a hard record to review, because there are so many factors going into a great listening experience, and the excellent work that EBS did here is only a portion of that overall experience. It’s still worth picking up I think, but I would not recommend that it be your only Verdi Requiem performance in your vinyl library, especially when the others mentioned cost substantially less.

Music 9/11

Sound 8/11

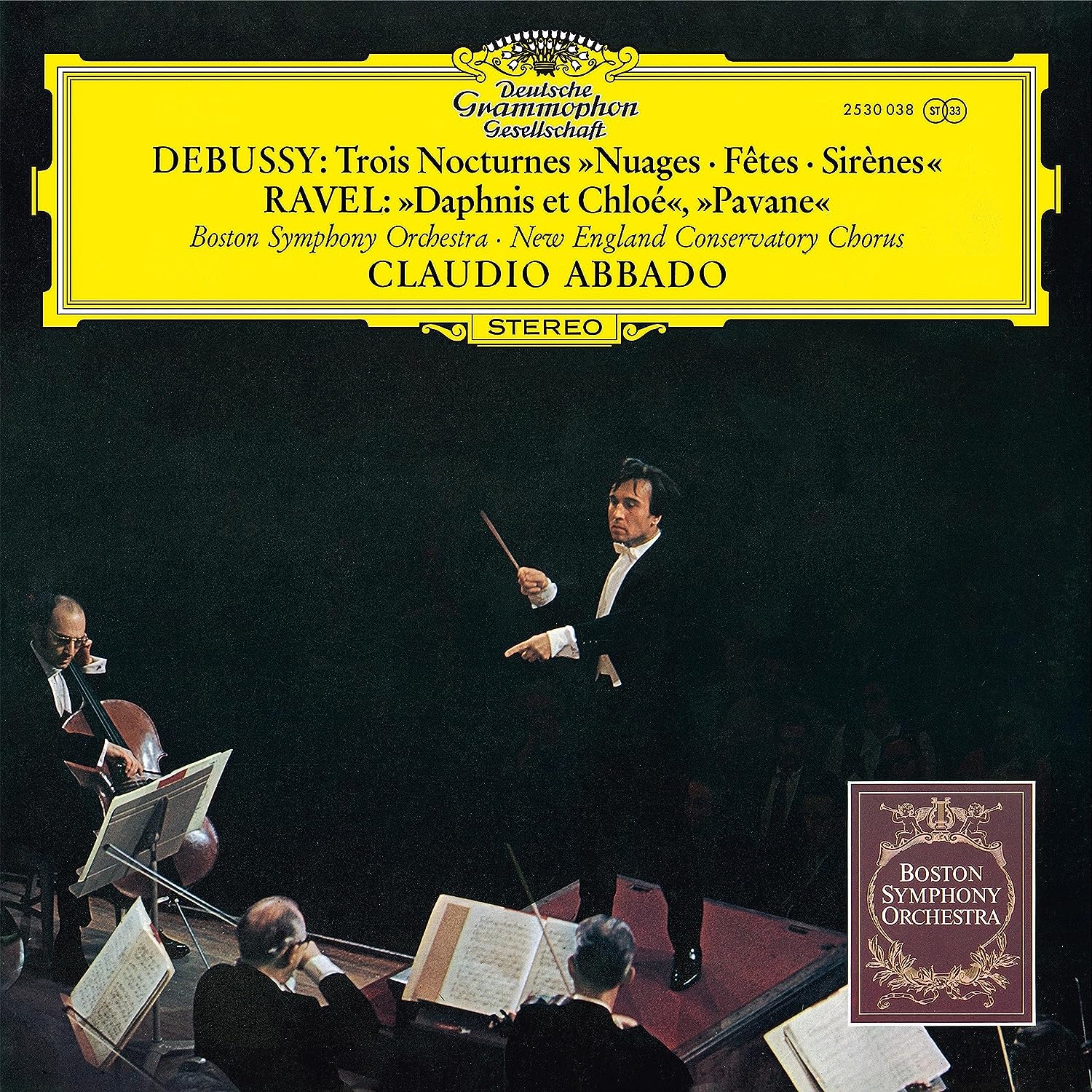

Claude Debussy: Three Nocturnes, Maurice Ravel: Daphnis and Chloe, Pavane for a Dead Princess

Claude Debussy: Three Nocturnes, Maurice Ravel: Daphnis and Chloe, Pavane for a Dead Princess

The Boston Symphony Orchestra conducted by Claudio Abbado

Recording: Boston Symphony Hall, February 1970

Executive Producer: Rainer Brock

Producer: Karl Faust

Balance Engineer (Tonmeister): Günther Hermanns

Remixing: Rainer Maillard

Cutting: Sidney C. Meyer

Limited Edition of 2200

The Boston Symphony Orchestra has had a long association with the music of France. French-born conductors served as music directors of the orchestra as early as 1918 with the appointment of Henri Rabaud, and then the following year with famed maestro Pierre Monteux, breaking the tradition of American orchestras hiring primarily German, Austrian, and Hungarian-born conductors. Record collectors will of course note the BSO’s fruitful recording tenure under Alsace-born conductor Charles Munch for RCA records. Munch, who led the BSO from 1949-1962, was considered a chief interpreter of 19th and 20th century French orchestral repertoire and recorded definitive performances of much of that repertoire during RCA’s golden “Living Stereo” years (and many of those records are in-print at this moment through Analogue Productions reissues). By the early 1970s Boston was not only the premiere orchestra in the western hemisphere for the performance of romantic and impressionist French music (Montreal would eventually catch up with Charles Dutoit at the helm in the early 80s), but it was perhaps the most refined group of musicians making up what was then called the “big 5,” a group of the absolute top American orchestras including Boston, Philadelphia, Cleveland, Chicago, and New York.

Claudio Abbado, who by 1970 was making waves as a young up-and-coming Italian maestro with a command of diverse repertoire, was never music director of the Boston Symphony, but he did record with them briefly over the years. This performance in question, a collection of French standards by Maurice Ravel and Claude Debussy, being his first meeting with them on record. The result is a disc of impressionist repertoire performed impeccably by an orchestra that knows it like the back of their hands, and a spirited conductor who has the knowledge and the technique to channel that foundation into something remarkable.

A Young Claudio Abbado

A Young Claudio Abbado

The three works on this record provide an excellent introduction to French Impressionism if you require one. In the art world, Impressionism refers to a period of painting from the middle to late 19th century featuring works by the likes of Claude Monet, Edgar Degas, and Pierre-Auguste Renoir. These painters focused not on an accurate photograph-like image of their subjects, but rather sought to portray the effects of changing light to invoke a sense of mood and experience through a scene. Later, around the turn of the century, the term would have a musical application to a loose association of French composers, beginning perhaps with Claude Debussy (1862-1918). Debussy never thought much of the term, instead referring to himself as a modernist, influenced by both the harmonic barrier breaking of Wagner, and the pentatonic sounds of the music of Java and other east Asian cultures. Nevertheless, Debussy’s music used formerly taboo compositional techniques such as parallel 5ths, large chords such as 11ths and 13ths, as well as unresolved harmonies and dissonances.

Claude Debussy

Claude Debussy

Perhaps the term impressionism fits so well into this music because of the way the composer describes it. Here are Debussy’s own words regarding his Nocturnes of 1899:

"The title Nocturnes is to be interpreted here in a general and, more particularly, in a decorative sense. Therefore, it is not meant to designate the usual form of the Nocturne, but rather all the various impressions and the special effects of light that the word suggests. Nuages renders the immutable aspect of the sky and the slow, solemn motion of the clouds, fading away in gray tones lightly tinged with white. Fêtes gives us the vibrating, dancing rhythm of the atmosphere with sudden flashes of light. There is also the episode of the procession (a dazzling fantastic vision) which passes through the festive scene and becomes merged with it. But the background remains persistently the same: the festival with its blending of music and luminous dust participating in the cosmic rhythm. Sirènes depicts the sea and its countless rhythms and presently, amongst the waves silvered by the moonlight, is heard the mysterious song of the Sirens as they laugh and pass on."

Another, younger, contemporary of Debussy’s in France at this time was Maurice Ravel (1875-1937). Ravel was the star pupil of another leading composer of the day, Gabriel Fauré, and as a young composer, became enamored with the music of Debussy, leading to a relationship that was half mentorship, half rivalry. Side two of this record contains the composer’s most-performed orchestral war horses: the Suite No. 2 from Daphnis and Chloe (1912), and the short work known in English as Pavane for a Dead Princess (1910), an orchestration of a piano piece (1899) he composed as a student under Fauré. Daphnis and Chloe is a longform ballet for orchestra and worldess choir based on the ancient Greek story of the same name. It is fitting here that it’s paired with Debussy’s Nocturnes as the third movement “Sirens” also uses this instrumentation. The most commonly performed version in concert settings however, is the second of two suites assembled from the piece, and encompasses much of the second half of the ballet.

The Pavane, while a beautiful haunting melody, does not actually intend to depict a royal funeral, but rather the title was to refer to a 15th or 16th century processional dance that might have been danced by young princesses in the Spain of old. In this regard, the beautiful French horn melody is not one of sorrow, but one of elegance and nostalgia.

Maurice Ravel at the piano

Maurice Ravel at the piano

As I alluded to earlier, Abbado’s reading here with the BSO is superb, matching both an extremely high level of technical playing and a riveting interpretation. Both Debussy’s and Ravel’s scores are technically demanding, with Daphnis in particular being of incredible difficulty (ask any Clarinetist or Flautist who has to play it on virtually every orchestral audition). I do not know of a reading from the analog era that can match the performance here in terms of player ability, just for fun I threw a couple of my Paray/Mercury records of the same repertoire, and while I love them dearly, the gulf in polish was wide. Not only that but the vocal performance here from the New England Conservatory Chorus found on Daphnis as well as the third movement (Sirèns) of the Nocturnes, far and away better than that of the Wayne State University Women’s Glee Club that the Detroit Symphony had access to. Even the playing the legendary EMI Cluytens recordings of Daphnis and Pavane (which I have in their “Classics for Pleasure” reissues) doesn’t measure up to what Abbado and the BSO showcase here (although I did prefer the natural, mid-hall sound of the classic EMI tube recording)

In both Daphnis, and the “Nuages” from Nocturnes, Abbado takes daringly quick tempos, but that agility never descends into any sloppy or ragged playing by the orchestra. Soloists on all fronts are outstanding. Special mention must go to the brilliant and shimmering flute solo in Daphnis by Doriot Dwyer (the first female woodwind principal of any major US orchestra) played with both sensitivity, and technical bravado, as well as supple horn solo by James Stagliano (in his final season as principal horn with the BSO) on Pavane.

As far as sound goes, this record was the best of the three, with a level of detail and imaging that fully complemented the complex scores of both composers. Both Debussy and Ravel orchestrate with incredible density, with many fluttering technical passages that serve as a bed of “texture” for longer melodic lines. It was a thrill to hear all these passages in such vivid and effortless detail, really allowing the listener to hear the pieces that make up the whole. The Boston Symphony Hall recording engineered by label stalwart Günter Hermanns, does not experience the same level of bass deficiency as the Berlin-recorded Verdi album, although I still did want for bottom end in the large orchestral passages. The tonal balance is also still what I would consider to be incredibly tipped-up compared to an RCA, Mercury or Decca recording, which are far more rounded in the frequency range and “full bodied”.

I think this record demonstrates the best of what the Original Source series can accomplish, the performance is one of the top in the repertoire despite stiff competition (Haitink on Phillips from 1980 is the only competitor I can think of that may beat it in terms of performance). Sound quality, while a bit bright and wanting in the low end, is also detailed, rich, and dynamically powerful. Only seldomly did I hear a bit of the trademark DG string “glassiness”, and while my pressing from Optimal was flat and quiet, my promo copy was slightly off-center leading to some audible pitch wobble on side two (minor, and nothing compared to the pitch problems of the old Classic Records reissues pressed back in the day at RTI). These are minor complaints and overall this is possibly my favorite release so far in the series— a must buy, especially if you don’t already have any of this repertoire in your collection!

Music 10/11

Sound 10/11

Johannes Brahms: The Piano Concertos

Emil Gilels and the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by Eugen Jochum

Recording: Berlin, Jesus-Christus Kirche, June 1972

Executive Producer: Günther Breest

Producer: Hans Weber

Balance Engineer (Tonmeister): Klaus Scheibe

Remixing: Rainer Maillard

Cutting: Sidney C. Meyer

Limited Edition of 2000

Of all the recordings reissued in this series so far, this one; Brahms’ Piano Concertos No. 1 and 2 recorded by pianist Emil Gilels and the Berlin Philharmonic with Eugen Jochum at the podium, is likely the most critically agreed upon pick for a desert island recording. Still to this day, Gilels’ 1972 reading of these works is praised by multiple generations in both the press and by listeners. It’s no wonder then that Deutsche Grammophon and Emil Berliner chose to trot out this war horse for the five-star treatment.

The first Piano Concerto in D minor by Johannes Brahms (1833-1897) was originally intended to be the composer’s first four-movement symphony. Well actually, it began life in 1854 as a sonata for two pianos, then a four-movement symphony, and then finally as a concerto for the piano that was completed In 1858. The first performance of the work in 1859 with Brahms himself at the piano, was received poorly. However, with subsequent performances in Leipzig, Brahms received a much warmer reception, and the piece developed critical acclaim. It should be no surprise reading about the creation of this work, that it is symphonic in scale and form, despite the three-movement structure typical of an instrumental concerto.

Johannes Brahms as a young man

The Piano Concerto No. 2 in Bb Major was completed in 1881, 22 years after the debut of the composer’s first concerto and a few years after the premieres of his first two full-length symphonies. It is written in four movements rather than the usual three, and is of a somewhat unusual length with typical performances lasting roughly 50 minutes (more on that fact later). It is notably more subtle than his first, with the opening melody coming from a lone French horn, from which the piano gradually takes over, rather than the crashing orchestral tutti that commences the previous work. It is certainly a work that demonstrates the composer’s more mature style, honed through his first two symphonies.

The pairing of Gilels and Jochum/Berlin on this 1972 recording works wonderfully, as both musicians as well as the orchestra were experts in this repertoire. Gilels had actually recorded the Concerto No. 2 once before in 1958 with Fritz Reiner and the Chicago Symphony, but it is his reading here with veteran Brahms conductor (and notable Bruckner expert) Eugen Jochum that is rightly pointed out as being the more mature performance. Jochum controls the Berlin Phil well here, providing incredible flexibility and control when the soloist requires it. The interplay between the orchestra and piano on these works requires a keen understanding of melodic relationships and give/take, which Jochum and Gilels manage with great success.

Gilels’ particular interpretation can be described as on the “serious” side, with large dramatic effects and tempos that linger on the slow side of normal, but I would not say they drag at all. Further, the intensity of Gilels’ playing is astounding. Comparing the performances here to those I had from Richter, Curzon and Rubinstein, none of them match the intensity and fire of Gilels' playing. At times it sounds like the pianist is hitting the keys with such force I was scared for the safety of the instrument. If you want your Brahms on the “lighter” side, this is not the recording for you, but personally I find both performances here to be invigorating, and much more emotionally involving than any other I own.

Pianist Emil Gilels

Pianist Emil Gilels

The recording is another one that in its day was sonically far outshone by competitors from Decca, RCA, and EMI. On the original pressing I had on hand, Gilels piano sounded overly round and muted, with little to no transient attack, while the orchestra had to it that classic DG “emerging from a mail slot” sound. Playing the new version was like playing a different recording, but right away I noticed something: this “new recording” was also demonstrating some problems.

My first observation was that the new remastering completely changed Gilels’ piano sound, now there were transients in spades, creating one of the most realistic bright piano hammer rings I’ve heard on record. The sound however, in places is still a bit hard and glassy, particularly the violin tone, which to me has that classic DG house sound that is just unpleasant and not at all what the instrument sounds like naturally in a hall. Now, the sound is rounder in the more subtle passages, but when Gilels really gets going, which in these pieces he tends to do quite a bit, to my ears, some of that accompanying string tone is quite abrasive. I do not think this is something Maillard and Meyer could really fix on their end, as it is clearly a sound baked into the recording, but it’s worth pointing this out, as throwing on, for instance, my ED2 wideband copy of SXL 6023 with Clifford Curzon on Decca yielded a much more tolerable string tone in the climaxes, even if it was not as layered, dynamic, or detailed.

My second observation was that EBS cut this record HOT, with explosive dynamics from both piano and orchestra. However, this brought to my attention some issues I was hearing in my playback. Specifically, I encountered tracking difficulties in two places: On side 1, I encountered difficulty tracking the large tutti sections in select passages during the thunderous first movement of the First Concerto. And on side 3, I encountered some difficulty in the final moments of the side, which is no wonder since Sidney Meyer and EBS cut this side closer to the label than I have ever seen on a record in my roughly 3,500-piece collection. This 2LP set is dynamic everywhere, including the first movement of the Second Concerto, however interestingly enough, my tracking difficulties were only encountered in these two aforementioned places, not in the main bulk of side 3, and not anywhere to be found in sides 2 and 4.

Now, for disclosure, I do not have the playback system of the caliber of our host and editor, but I do think my analog front end is competent, and competently set up. It features a Hana Umami Red cartridge mounted on an Acoustic Signature TA-1000 tonearm and Pure Fidelity Horizon turntable. At the beginning of this saga (and yes it did become a saga), my cartridge was aligned to the Stevenson alignment via my Dr. Feickert protractor.

Dismayed by what I heard as audible distortion, and questioning whether that distortion was from the recording, mastering, cutting, or playback, I asked Michael Fremer to play his own promo copy and report back with the results from his system. The file he sent me; a rip of the second half of side 1 played on his Lyra Atlas Lambda SL, to my ears, contained the same distortions I encountered in my playback on my own system.

Wanting to get to the bottom of this problem, we quickly contacted Rainer Maillard and Sidney Meyer at Emil Berliner Studios with our concerns. Rainer immediately got back to us and I will quote the most pertinent portion of his reply here:

"With the Original Source Series we try to go to the limits. To get more dynamics and more signal to noise ratio onto the disc, we have to use less compression on the disc. This means, we are cutting with more level, which means technically that the maximum velocity is higher.

There are two different ways of distortions possible while play back. The more known distortion refers to the high frequencies, when the wave length on the disc get short in relation to the needle. This does not happen on Brahms. (best known with S sounds of singers). We checked all parts to avoid these play back distortions before cutting. There is another possibility of play back distortions of low and mid frequencies possible. If you have a very high Level of a low frequency (like the fundamental of a timpani) the size of the needle is unimportant, but the velocity could be very high. There is no specification for cutting LPs about a maximum of velocity. What we know, different pick up systems and amplifiers could handle maximum velocity of low/mid frequencies in a different way. Sidney checked this passage with two different systems. Optimal also listened to the mother with different systems. On our systems the sound is clean. (As far as a loud passage could be clean. Listening to a 0dB sine tone of a test LP you hear a lot of distortions. You do not believe how much. But with a sine tone there is nothing to hide, no masking)"

With the idea now that there was no pressing defect, and that it was simply a difficult to track side, Michael and I set about trying to figure out the correct conditions needed to track it. On my end, I decided to ditch the Stevenson alignment (the alignment most commonly favored for classical music due to its tracking abilities in the inner groove, but higher distortion midway through the record) and went with the native alignment geometry provided by the Acoustic Signature alignment jig that came with my tonearm (I have read somewhere that it is close to Stevenson alignment, but considering the amount of change in the overhang it required, it may be something else). On Michael Fremer’s end, he installed a Shure V-15VxMR on his rig; a notorious vintage cart known for its tracking ability.

The Shure V-15VxMR

The Shure V-15VxMR

Michael Fremer was kind enough to record me some excerpts of the Brahms concertos with his Shure V-15VxMR, while Sidney and the gang over at EBS were kind enough to send some samples of “high velocity” portions of the Brahms concertos recorded with their test setups. One, a very sophisticated EMT setup, and the other, a basic setup featuring a Pro-Ject turntable fitted with an Ortofon 2M Red. These samples they claimed, showed that setups could track these demanding passages cleanly. In addition to these audio samples from my editor, as well as the team at EBS, I also was able to audition this pressing on the system of friend and fellow record collector near me who among some rather high-end gear, utilized an Ortofon Cadenza Blue, that was set up with the Ortofon alignment protractor as well as the Analogue Productions test record and the Musical Surroundings Fozgometer.

On my end, while I was able to reduce the number of times I heard recognizable breakup in the tracking of the cartridge, particularly in side 1, I could not eliminate them entirely. On side 1 of the record, I heard breakup in the large tutti section at the beginning of the movement, as well as ever so slightly in the final tutti crescendo at the end. I again did not hear any distortion present on side two in the first concerto, and none on side four in the second concerto. On side 3, that close-cut inner groove still resulted in issues on the final 30 seconds of playback, particularly the last chords.

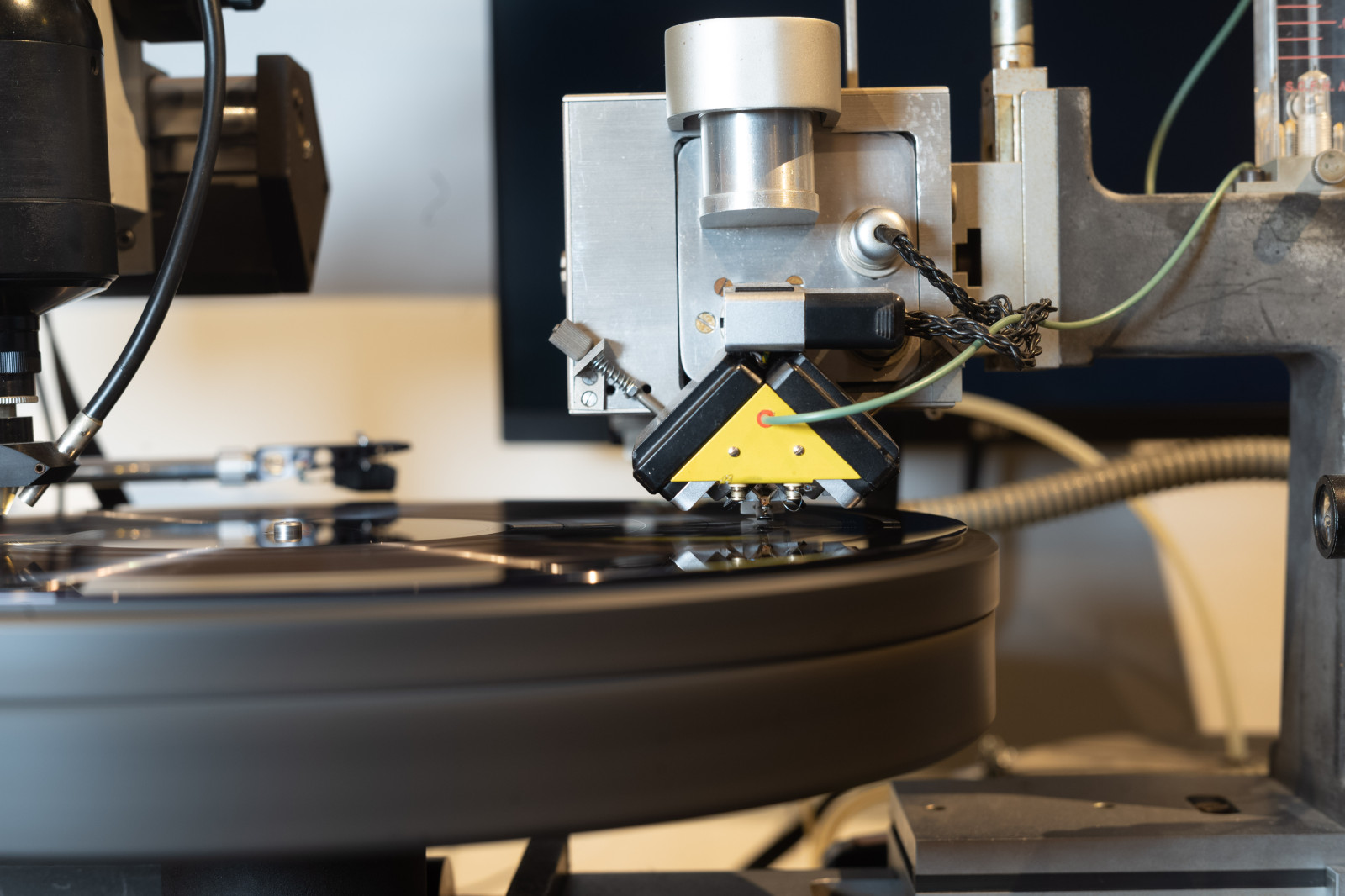

Now, this third side of the set features two movements, and in my opinion there was no reason why these movements shouldn’t have been split up between sides, other than that it would have cost too much money to include a third LP in the set. Examining the original Deutsche Grammophon pressing, one sees that the solution for them at the time was to use lots of compression, and keep the grooves far away from the center label by lopping off bass and dynamics. Because of the cutting goals of this series, Maillard and Meyer of course were cutting much wider groovers, and no doubt cutting dynamic grooves that close to the label is a feat of skill, but it’s up to listeners and reviewers to determine if the skillful gamble payed off. You can see my Umami Red tracking this inner groove below, and you can also take a gander at how wide and treacherous these grooves are, so close to that center label and with barely any room for a run-out groove.

The Hana Umami Red tracking the inner groove of side 3

Now I should say, in reference to Rainer’s above commentary, that not only did my setup handle the bombastic moments of Concerto No. 2 with ease (until the final inner groove), but my system in the past has tracked some very dynamic, transient and bass-heavy records. These include the 45rpm Analogue Productions Winds of War and Peace, Reference Recordings’ Rite of Spring, EMI’s Shostakovich 8 with the LSO, and of course everyone’s favorite recent tracking test record, Blue Note’s Picture of Heath. So, needless to say when my cartridge and tonearm could track the above records, and not this one, I was quite frustrated.

When Michael got back to me with his recordings made with the expert-tracking Shure cartridge, I knew we were in trouble. The Shure tracked the first movement much better than his previous Lyra to my ears, and better than my Umami, but it still experienced some brief distortions during the climaxes of movement one, as well as in that infamous inner groove on side 3.

From my listening, with my ears that both hear these instruments live on a daily or weekly basis, but also that are maybe a little bit younger and a little more sensitive to overtones than many other listeners out there, I heard distortion on every single setup including in the files EBS sent over that were supposed to demonstrate clean sound on their end. Troubling.

The best trackers with the fewest issues were Michael’s Shure cartridge, as well as EBS’s EMT setup. The Ortofon 2m Red experienced many of the issues I had, breakup in large tutti “hits” at the beginning and end of side 1. My friends’ Ortofon Cadenza setup displayed even more distortion in these sections (maybe 5-7 examples in this movement as opposed to my 2-3). The Shure cartridge on our host’s system, to my neurotic ears, only yielded unpleasing colorations twice, once in the final hits of the first movement, and once again during that horrible to track inner groove on disc 3 in the second concerto. The EMT system provided by EBS also handled things very well, but I did hear audible breakup very slightly in the first movement, and especially in the inner groove with the finale of the 2nd movement of the second concerto.

So, what does that tell us? Well, possibly that I’m overly sensitive to these issues, but I think it’s troubling that rips provided to me by EBS themselves portray what is to me, an unacceptable level of distortion in select places that brings me out of the music. Now, it should be pointed out that in most circumstances a difficult to track record should not usually effect the reviewer’s judgement on sound quality. We learned this from the Picture of Heath debacle. But in that example, most listeners who were able to make slight adjustments to their setups, and/or who processed sufficient gear, could get a satisfactory result. In this unfortunate example, I could not identify a way of setup or pairing of equipment able to track this record to my own subjective satisfaction. But you also don’t have to take my word for it, you the readers can be the judge with the sound samples below:

(Our plan to present you with files so you can listen for yourself has been thwarted by the "copyright police" even on short excerpts. We are trying to resolve this with DGG)

For this reviewer, this is the one record in this marvelous series I was truly disappointed by. Not only disappointed because of the inability for these particular spots to be tracked by any setup I encountered, but also because elsewhere in the cutting, the sound on these two records is so dynamic and engaging, particularly in the Second Concerto and especially in the piano sound. EBS clearly tried to do great things here, but there is a fine line where eventually you over-season the roast, and I fear in their goal of getting the very best dynamics and headroom out of this particular title, they overshot the limits of what can be tracked cleanly by most good systems. To my very subjective ears, this is an example of a record that was so close to being great, but these talented engineers might have flown a little too close to the sun on this particular outing.

(I have to add here that my old ears—and also not being someone who plays in a symphony orchestra— didn't hear some of these issues at all and in the "near the label" cut, accepted it as commonly encountered "close to the label "waveform crunch". The files will give you an opportunity to listen for yourself_ed.)

Music 11/11

Sound 6/11

.png)