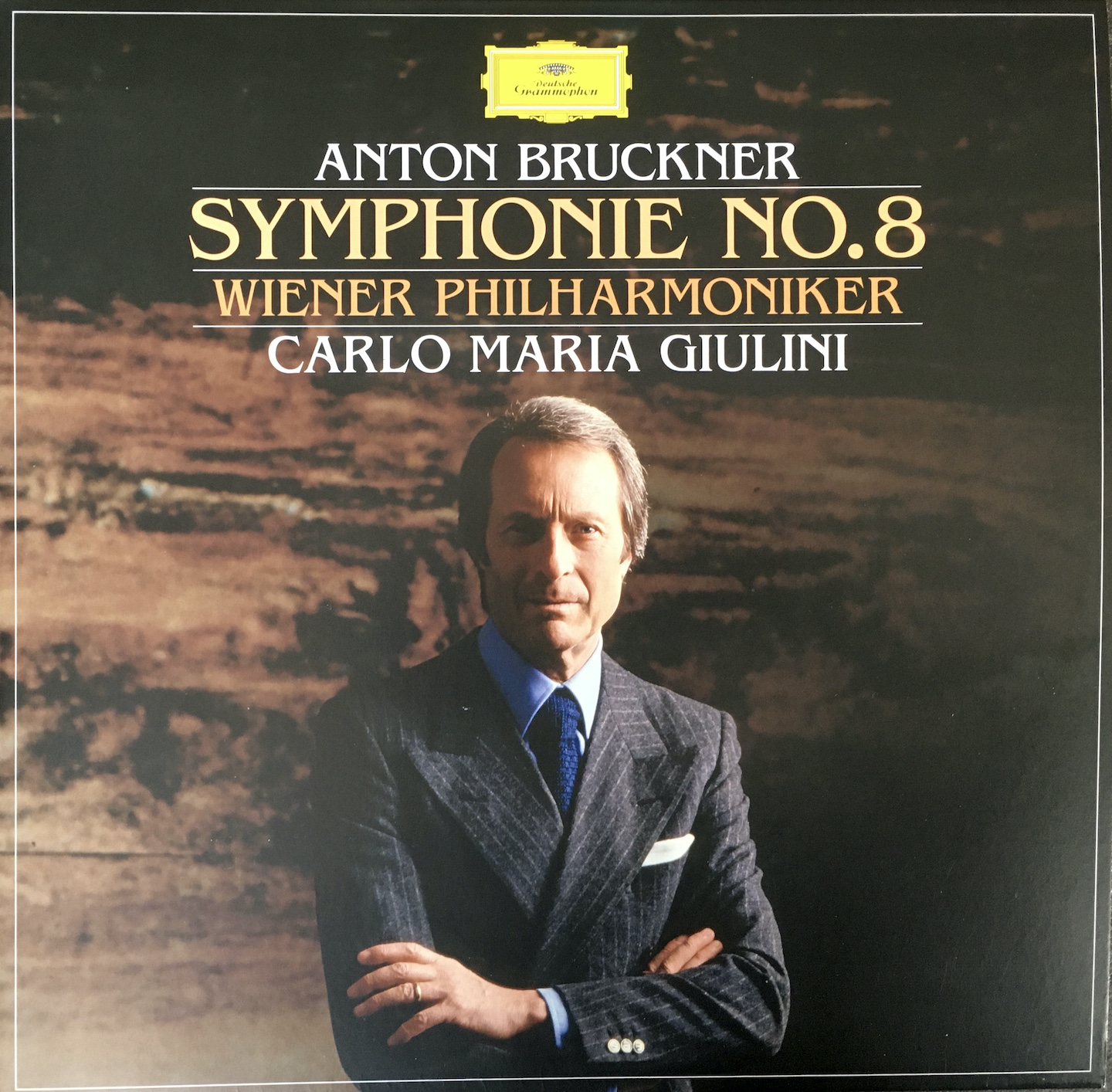

Giulini Meets Bruckner: DG’s Classic Recordings by the Italian Maestro Given New Life on Vinyl by Emil Berliner Studios - Part 2

The Philosopher Poet of the Podium meets the Arch Austrian Romanticist in Vienna, and the result is something very special for the Bruckner Bicentenary

From the opening bars of the 8th Symphony we are in a different world than the 7th: more craggy, disjointed, full of foreboding. Just wait until the brass have their first big entry, with Wagner tubas and contrabass tuba adding their distinctive timbre to the bass. This is a symphony where the brass eruptions can truly get out of control, but Giulini characteristically lets the Viennese brass (and timpani) off the leash just enough to make their point without tipping over the whole apple cart. A typical example of how he keeps everything in balance is the end of the first movement, with its hall-shaking brass peroration which then gives way to a defeated, disjointed series of phrases in the strings, some pizzicato, that just, well, end.

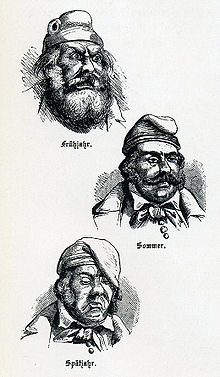

The brass (4 Wagner tubas, 8 horns, 3 trombones, 3 trumpets, plus contrabass tuba) and timpani return with a vengeance in the second movement Scherzo. The writer of the again excellent sleeve note, Mosco Corner, likens this most aptly to a “Dance of Titans”. Corner also notes that: “Bruckner described this movement as an image of the ‘Deutscher Michel’, symbol of the quirkiness and peasant-like uncouthness in the German national character.”

Representations of the Deutscher Michel in the magazine Eulenspiegel in 1848

Representations of the Deutscher Michel in the magazine Eulenspiegel in 1848

The adjoining Trio features - unusually for the composer - harp, and is redolent of the tranquil low pastures of the Austrian Alps.

The Adagio, running close to 30 minutes, is one of Bruckner’s most lyrical and passionate creations. It occupies similar emotional, heart-breaking territory to Mahler’s great slow movements. At several of the climaxes Bruckner utilizes those same harmonic shifts I so loved singing in the Motets. At these moments he intensifies the beauty and heartbreak with harp arpeggios, instantly reminiscent of Mahler’s use of the instrument in the famous Adagietto of his own 5th Symphony. The effect is ravishing, spellbinding, guaranteed to have you catching a lump in your throat.

Here you will maybe miss the detail, warmth and almost tactile quality a good analogue recording would have added to the strings, but again the DG team have gotten very close to the ideal. Ah, those Viennese strings…! As the movement winds towards its poignant end, you may be moved to reflect, in the words of Caliban speaking to two shipwrecked sailors on the enchanted isle where they have awoken, in Shakespeare’s The Tempest:

Be not afeard; the isle is full of noises,

Sounds and sweet airs, that give delight, and hurt not.

Sometimes a thousand twangling instruments

Will hum about mine ears; and sometime voices,

That, if I then had waked after long sleep,

Will make me sleep again: and then, in dreaming,

The clouds methought would open, and show riches

Ready to drop upon me; that, when I waked,

I cried to dream again.

The final movement crashes in with a strident, military brass fanfare accompanied by pulsating strings. Thrilling stuff, that gives way to softer, more lyrical material. By the end of the movement Bruckner re-introduces thematic material from across the entire work, culminating in probably his most triumphant peroration in the whole cycle, brass a-blaring. The Gods ascending to Valhalla indeed! Let’s just say that here neither conductor nor orchestra hold back.

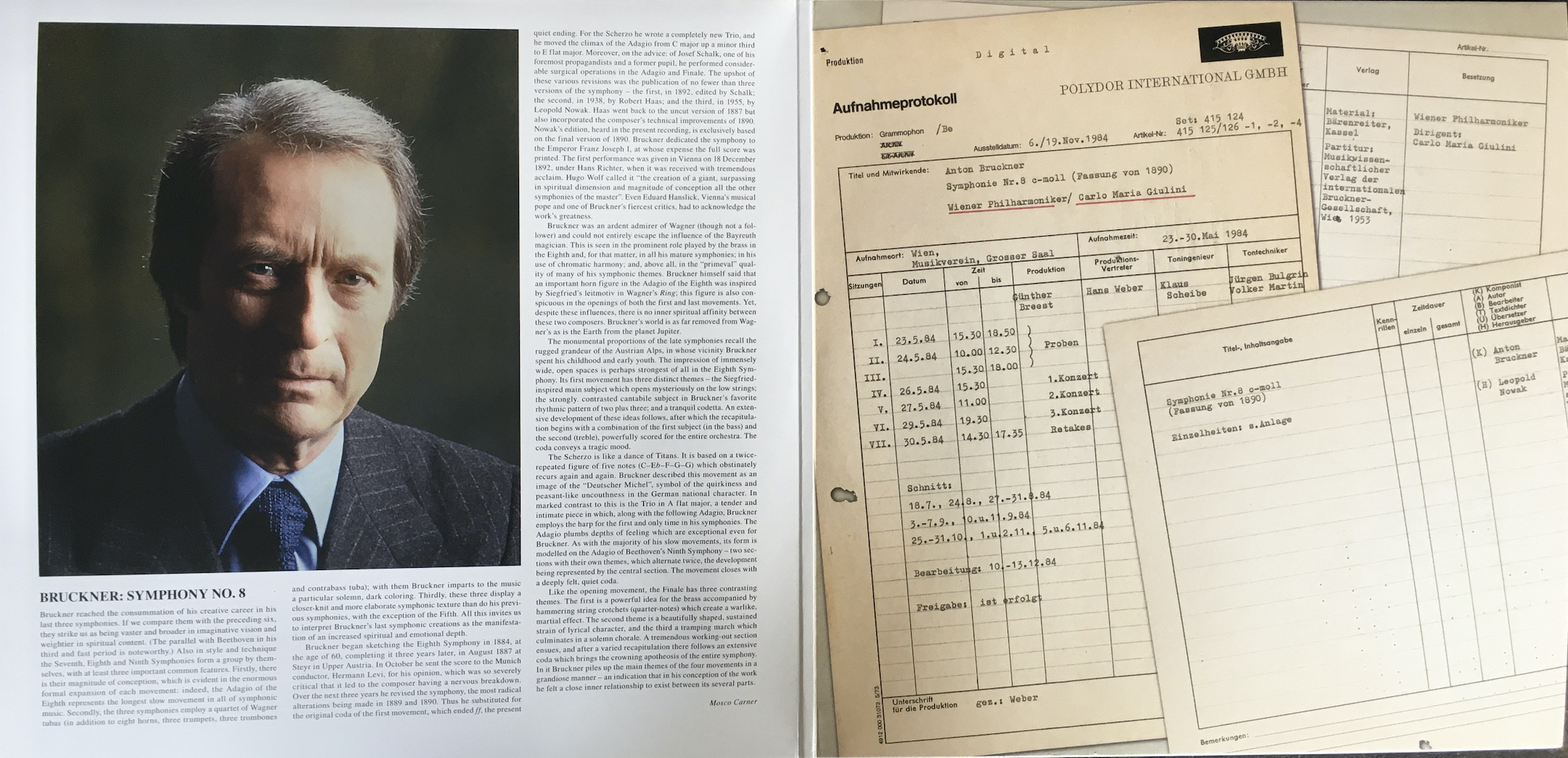

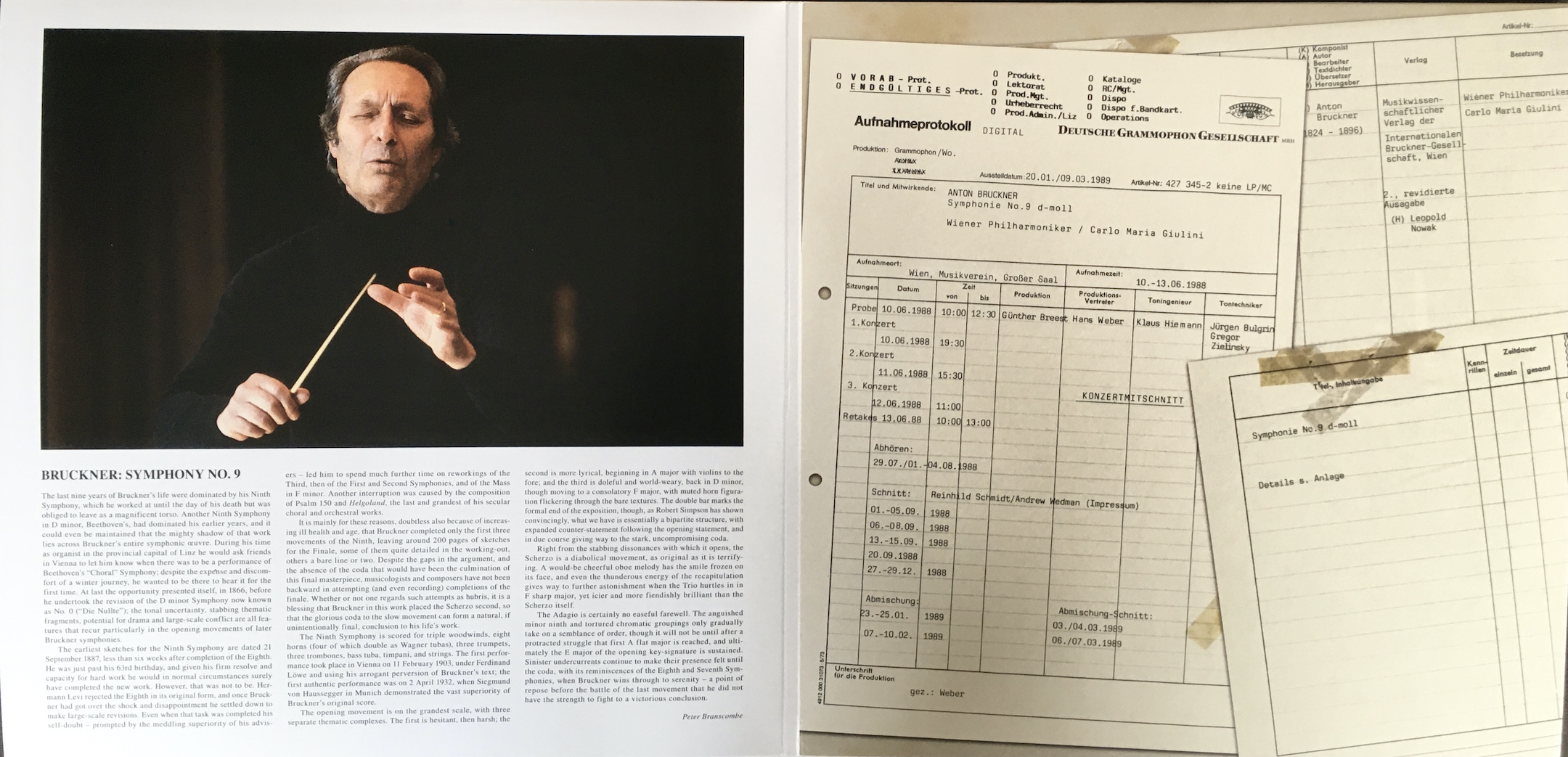

Gatefold of the new vinyl edition

Gatefold of the new vinyl edition

Now my go-to in this symphony has long been Karajan in Berlin (part of the cycle about to be reissued in the Original Source Series) or his late re-recording with the VPO, a unique live document. Just listening to the opening of the last movement alone on his earlier BPO version will have the hairs on your head standing on end. I am going to wait until I hear the new Original Source version to pass final judgment, but Giulini gives Karajan a substantial run for his money. This is Bruckner at his most monumental, epic, grandiose, but also bellicose (which suits Karajan’s own temperament well) - fully in control of his vast resources and profoundly confident in his formal design - but equally demanding of his interpreters and performers in every regard. It’s a very hard symphony to pull off, but Giulini and the VPO again find humanity and tenderness within all the rugged grandeur.

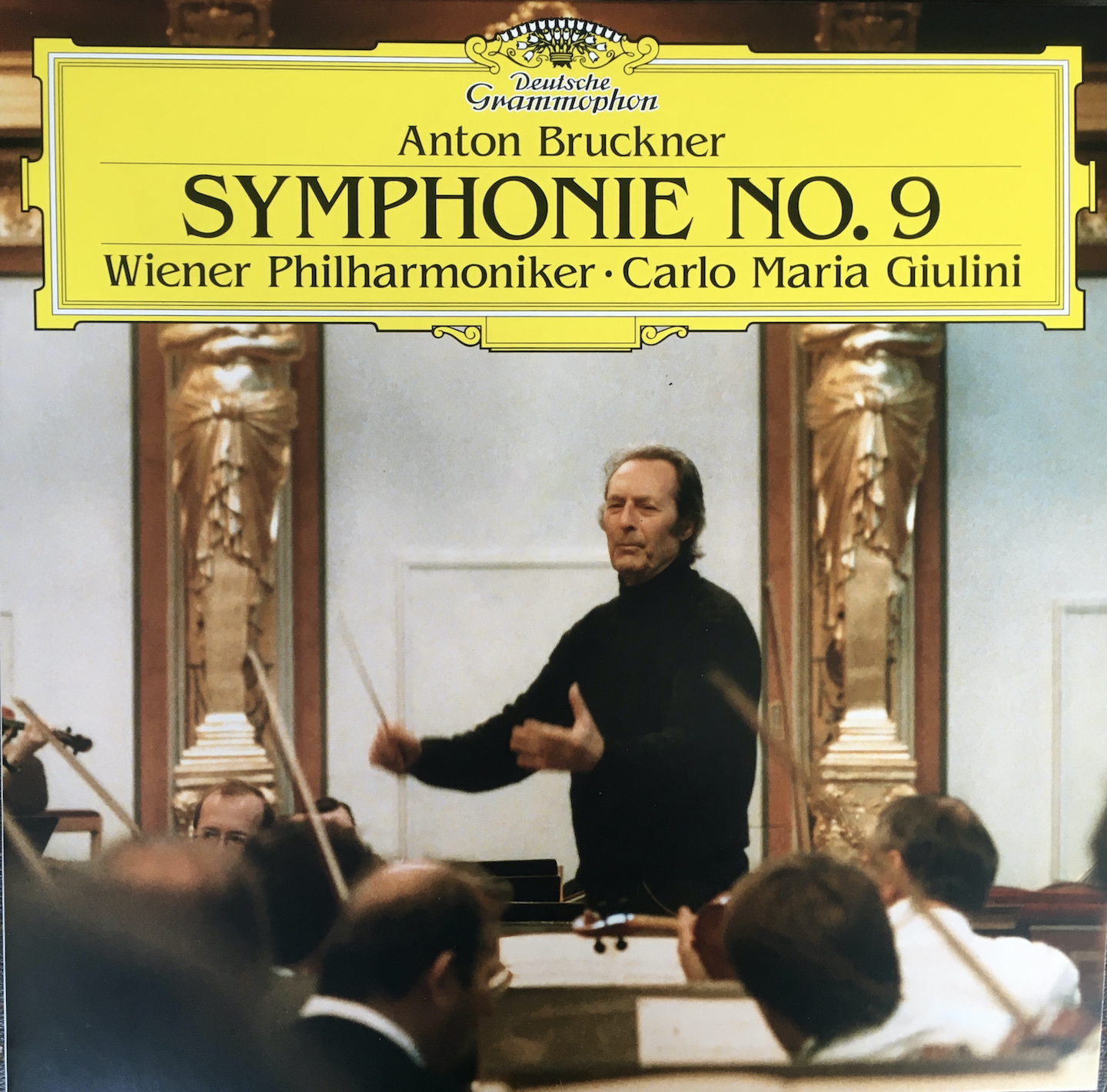

With the 9th Symphony we find Bruckner entering more forward-thinking, even modernist territory. The last movement (originally intended as the third - the composer died before completing the work) is full of what appear to be half-formed gestures. Its tone is far more bleak than its two predecessors, reminiscent (or, to be more accurate, predictive) of Mahler’s similarly end-of-life statement in his own 9th. Of this movement, the great 20th century composer Igor Stravinsky said this:

“I think that the Adagio of the 9th must be accounted one of the most truly inspired of all works in symphonic form. Indeed, Mahler seems much less original than Bruckner when one knows this music, and no composer of this period is so personal a harmonist as Bruckner.”

There is a challenging monumentality to this work, along with a sense of fragmentation, both of which Giulini captures in all their facets. This has long been my personal benchmark recording (along with Carl Schuricht’s far earlier EMI/Columbia version, also with the VPO, available as a very expensive OG, or a fine Testament vinyl reissue). Giulini and the VPO’s Scherzo alone has to be heard to be believed: it manages to be both fierce and dance-like at the same time. No-one captures this movement like Giulini and the VPO, with the brass having a field day.

The live recording by Klaus Hiemann has always been very good indeed, one of the finest examples of DG Digital engineering from any era. The sound is a little drier than for 7 and 8, by virtue of the fact this was recorded “live” with an audience present to soak up some of the Musikverein’s reverberation. When the brass gets going - man, your listening room is to going shake, rattle and roll.

The expensive Esoteric CD/SACD of a few years ago improved matters of detail, dynamics and general listenability enormously from the original CD-only release, and if you already have that - and a top-rate digital front-end - you may not feel any special need to shift allegiances to the new vinyl (only available as part of this set). But for the vinyl enthusiast this new EBS cut is a real treat, enshrining a truly superb, and classic, DG recording - both performance-wise and engineering-wise - on our favorite medium.

Giulini's recording of the 9th is very special indeed: a thrilling account of this incredible work, rivaling in my memory an awesome (in every sense) live performance I heard Bernard Haitink give with the Dresden Staatskapelle at the BBC Proms way back in the 1980s.

It caps a wonderful set of records that does Bruckner's masterpieces proud.

Gatefold of the new vinyl edition

Gatefold of the new vinyl edition

The Sound

Now I know some of you may be scratching your heads at the fact that I am raving about the sound of these records as much as I am about the performances. These recordings are, after all, early DG digital - not a period associated with audiophile quality.

Well, like you, I wanted to know a little bit more about why these records sound so good. Yes, they were mastered and cut half-speed, something Emil Berliner Studios only ever does from digital masters. They sound immeasurably finer than the recent Britten War Requiem reissue I reviewed here recently, which was similarly mastered and cut half-speed at Abbey Road Studios As I have long suspected, there is nothing intrinsically wrong with half-speed mastering - it just has to be done right.

There was no better person to ask about all this than Rainer Maillard himself, responsible with cutting engineer Sidney C. Meyer for creating these sonic beasts, as well as all the other Original Source records that have been putting our systems through their paces for the last year.

He has some fascinating insights into the recording process of all those many years ago, and gave some background on the talent in the control room, and in the mixing and mastering suites.

I began by asking about the DG transition to digital:

“To my knowledge the first digital test took place in 1976 with a Sony PCM1.

“The first digital multitrack recording was in 1978. From 1979 they did most of the production in both the digital and analogue domains. (2-track on PCM 1600 or multitrack on 3M).

“In 1980 they stopped doing the parallel analogue recordings.

"In terms of quality, engineers had to learn how to use this new technology quickly. Artifacts must have been horrible at the beginning; this improved from month to month. (Unfortunately not as good in 1980 with Karajan’s digital Bruckner recordings of Symphonies 1-3).

"The biggest challenge at this time was not recording digitally, it was editing. In classical music it was essential to be able to edit (not so important for pop music)

“And as Karajan insisted on being able to still record with multi-track capability, they needed a solution for multitrack editing at the same time - just like for 2-track. So they worked first with a prototype from Sony for 2-track, and found a solution for 3M multitrack (see the pictures on the EBS history website). Later they found an editing solution for the Sony 3324 as well.

“Everything started to go smoother around the year 1990, when Stefan Shibata joined DG (Klaus Hiemann had been looking for an expert in digital audio). A new department with its own engineers developed their own new and better microphone preamps and converters. They modified the 24-track, 16-bit Sony 3324 to 16-track 24-bit, built a noise shaper, and so on. From 1994 everything was done in 24-bit. At this time digital audio was not so easily available on the market like today. DG spent a lot of money on digital technology. Also digital multitrack editing with a workstation was a completely new tool.”

I continued by asking Rainer specifically about Giulini’s producer, Hans Weber, and the two engineers responsible for recording these three Giulini performances: Klaus Scheibe (Symphonies 7 and 8), and Klaus Hiemann (Symphony 9).

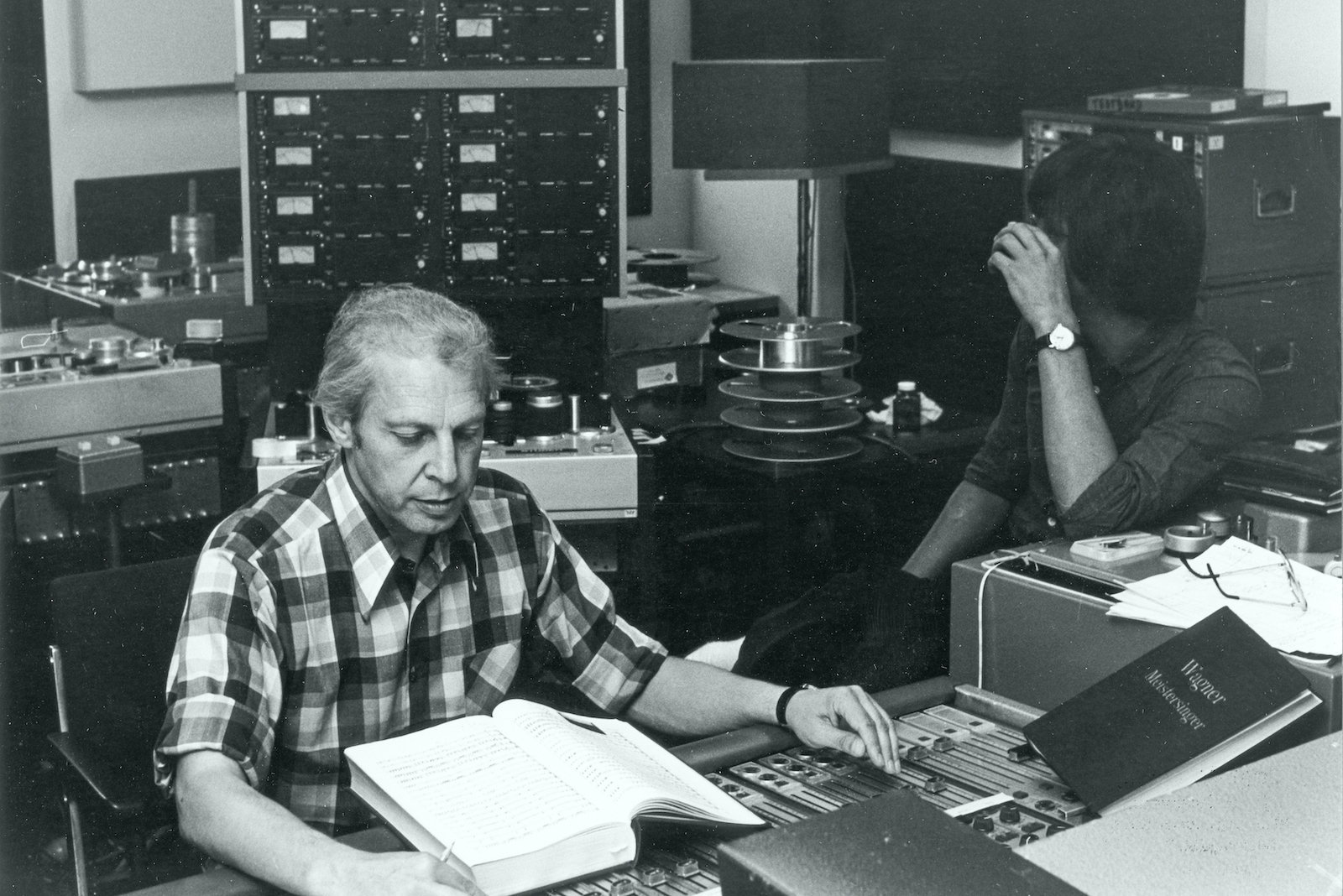

Hans Weber and technician Wolf-Dieter Karwatky editing analogue 16-track (photo: Rainer Maillard/Emil Berliner Studios)

Hans Weber and technician Wolf-Dieter Karwatky editing analogue 16-track (photo: Rainer Maillard/Emil Berliner Studios)

Maillard:

“Producer Hans Weber joined DG in 1957 and was responsible until 1997 for most, if not all, of Giulini’s recordings. He also worked with Carlos Kleiber, Karajan, Bernstein and many more. I think he was the most outstanding DG producer. As a trained musician and conductor himself, he was an equal partner to the label’s great conductors - highly respected, much loved.

“Weber was very serious, extremely quick-witted and had a great sense of humor. Unlike many other producers, he spoke over loudspeakers and not over a telephone with the conductor during the recording sessions, so all the musicians could also hear what he had to say. This meant that the mood during the sessions could change abruptly from the utmost professionalism (due to his seriousness) to laughter (because of that sense of humor). He was also - again in contrast to other producers – always present during the editing and mixing in post-production at the DG recording centre. However, he always gave the sound engineers a lot of freedom during this part of the process, and didn't interfere too much in their areas of responsibility, seeing his role (in terms of sound) more as a team player.

Hans Weber (l.) and Klaus Scheibe mixing at Recording centre Hannover-Langenhagen (Photo: Rainer Maillard/Emil Berliner Studios)

Hans Weber (l.) and Klaus Scheibe mixing at Recording centre Hannover-Langenhagen (Photo: Rainer Maillard/Emil Berliner Studios)

“Klaus Scheibe studied on the Tonmeister course in Detmold (Günter Hermanns and his generation did not have any formal sound engineering education). Scheibe was an excellent pianist too. I never saw him listening to a recording without the score. Because of his background as a musician, he tried to “translate” the score to a recording. That’s why all his recordings sound “right”. This is not necessarily a traditional audiophile approach, where you are thinking more in terms of translating a sound to a recording.

“Giulini 7&8 were recorded by Scheibe directly to a 2-track Sony PCM 1610. If I would have any concerns about the sound (which was driven by the score), it is that it does not sound as “audiophile” (whatever this means) as it could. Trying to get what for me is a priority - a more “open” sound - was not a priority for Scheibe. For this latest transfer, in some frequency bands I just fiddled a little bit with a MS-matrix in combination with our self-programmed digital cross-over - which works without any artifacts!!!. Nothing special. Almost old-fashioned. So I got a more “open” sound without any major treatment: the result was small changes with a good overall result.

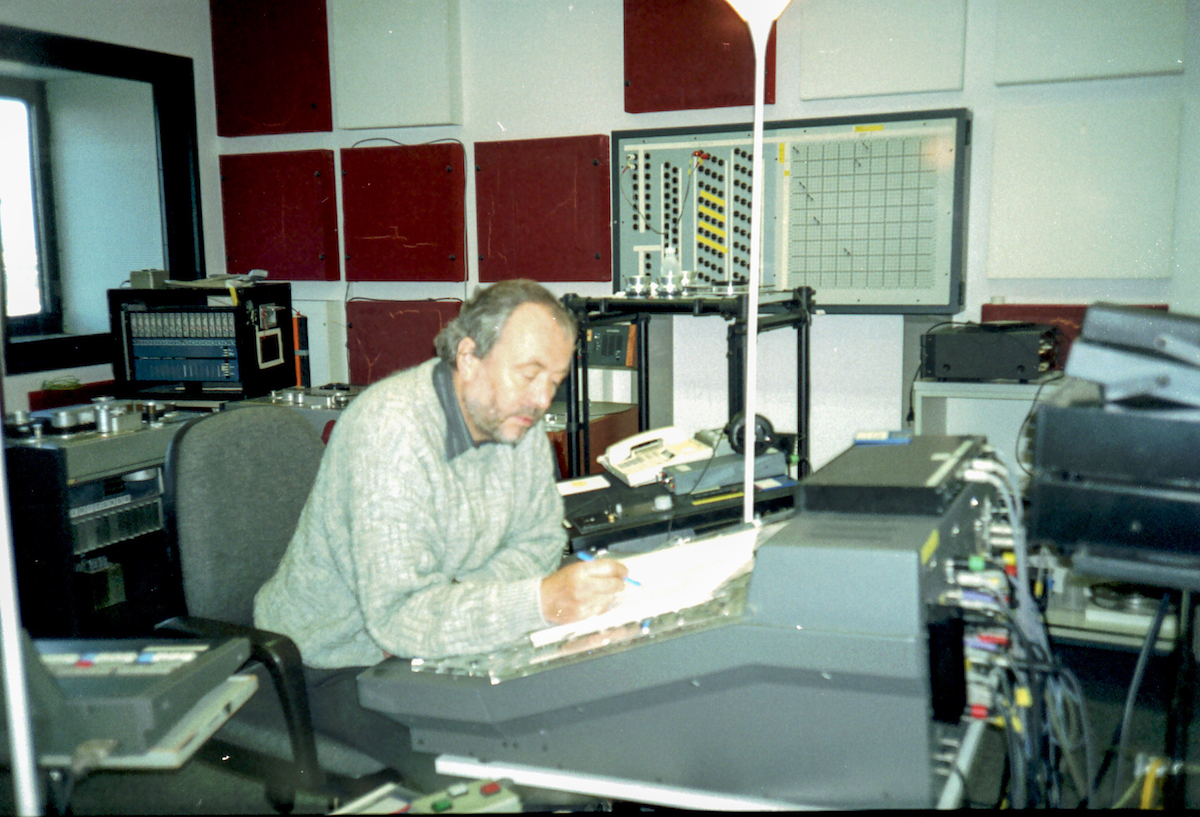

Klaus Hiemann mixing at Recording centre Hannover-Langenhagen (Photo: Rainer Maillard/Emil Berliner Studios)

Klaus Hiemann mixing at Recording centre Hannover-Langenhagen (Photo: Rainer Maillard/Emil Berliner Studios)

“Klaus Hiemann also studied at Detmold, and was also a good pianist. But he was always interested in sound (in addition to the score). And he was the engineer at DG who took sound quality most seriously, both in the analogue arena and, especially, in the digital arena. He was always pushing for the highest quality. He was aware of the limitations of analogue and digital (they are different for each). For digital recordings he forced DG to build its own Analogue-to-Digital Converters (better than what could be bought on the market). He asked Sennheiser to build new microphones. He pushed for the change to 24-bit from 16-bit technology (ahead of everyone else). He also saw the advantages of doing the mix in the digital domain (if you already had a digital recording) by using delay on the spot microphones. This could make a huge difference (depending on the setup - it does not always work). Bruckner 9 was one of the first releases where he combined special new spot microphones (figure of eights) by Sennheiser with the delay to the main microphones. The result is that it almost sounds like a two microphone recording - and therefore a purist, “audiophile” recording. (Yes, it does! - MW).

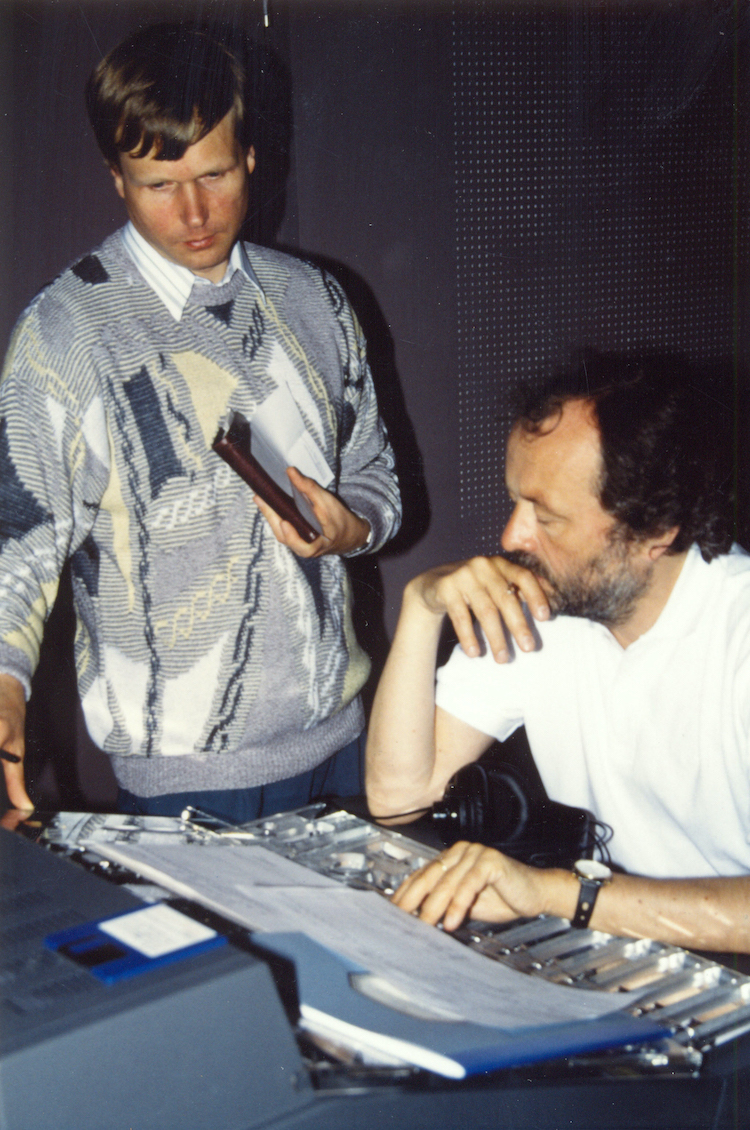

Technician Rainer Hoepfner (l.) and Klaus Hiemann working on the first recording with the new Yamaha DMC 1000 mixing desk, built in collaboration with DG (Photo: Rainer Maillard/Emil Berliner Studios)

Technician Rainer Hoepfner (l.) and Klaus Hiemann working on the first recording with the new Yamaha DMC 1000 mixing desk, built in collaboration with DG (Photo: Rainer Maillard/Emil Berliner Studios)

“So when it came to mastering the Bruckner 9th for this new vinyl edition, there was really no need to do a new mix… However, as we always go back to the original masters for these new vinyl releases, I took the 24-track multitrack original and remixed it. There were two advantages to doing this: the output now has more than 16-bit and the common digital loudness compression used on all CDs could be omitted. For Bruckner 9 I did not use any MS-matrix - there was no need for it.

“(About tools: nowadays there are so many digital mastering tools for all kinds of work. But we often try them with a phase check and find out that many of them do some additional processing that they are not supposed to do. It’s the same with analogue - there most of the tools add a “sound” too. We have two clever guys working at EBS, and we asked them to program some nice small digital tools for us. We make absolutely sure that these tools are only doing what they are supposed to do - ie. not adding any other “sound” or artifacts).

“Both Scheibe and Hiemann had a huge influence on the new generation of engineers like myself, who began working at DG in the late 1980s. In his last years, Klaus Scheibe took over the “Final Quality Control” department at DG, concerned with listening to the final masters and checking all technical and musical issues. He was very strict with us. He always criticized us (in a nice way) and asked us to do a remix or to try harder (at this time DG was not always thinking about money or its budget - unthinkable today). And Klaus Hiemann always shared new ideas with us concerning ways to improve the sound of our recordings, mixes and masterings. The recordings of these two engineers sound quite different from each other, but both are good. The only differences reside in matters of taste. Sharing knowledge amongst engineers was a normal part of the work culture at DG.”

Carlo Maria Giulini

Carlo Maria Giulini

In Conclusion

This Giulini box is an essential purchase for the Bruckner lover. I would argue it’s also essential for the Bruckner newbie, because these performances are so utterly ingratiating, and capture something in the music that not many others do. They invite you in and then astonish you with their range, variety and power. In its essence, Giulini humanizes Bruckner without shortchanging the Alpine scale and heft of these titanic works. I can think of no better way to first enter the world of Bruckner.

As to sound - no, these are not the last word in analogue goodness. And no, they do not have that same three-dimensional space into which the music can seemingly expand without limit, gob-smacking immediacy, dynamics from here to tomorrow, yet also detail and finesse of the best of the Original Source series.

But these recordings do get an awfully long way down the road towards that ultimate sonic “boom”. They serve the performances, the sound of the orchestra, and the sound of the orchestra in that very special hall to the extent that you will rarely feel short-changed in the sound department in any significant way. I had a hard time (as is often the case) in settling on a final number for the sound grading. Yes, these are early digital recordings, and they may lack to some degree the "breath of life" you get from the finest analogue. But boy are they really, really good (especially the 9th), so my final 8/9 is on the generous side. Frankly it's amazing how Maillard and Meyer have wrung every last ounce of magic out of nearly 40-year-old digital masters.

These recordings have always been considered to be very special within the vast riches that litter the Bruckner catalogue, and in their new refurbishment they sound fresher and more vital than ever.

My copies from Optimal were dead quiet and flat, all pressed with one movement per side, so there is no trace of inner groove distortion, even on the longest side: the 3rd movement of Symphony 8 clocks in at 29:16, the grooves wisely kept well away from the centre label. Lacking concerns about side length, cutting engineer Sidney C. Meyer is therefore able to exercise her formidable Formula One driving skills on the lathe and in the grooves with comparative freedom. The resulting sound will expand magnificently to fill your listening-room with all that Bruckner Big Bang Goodness!

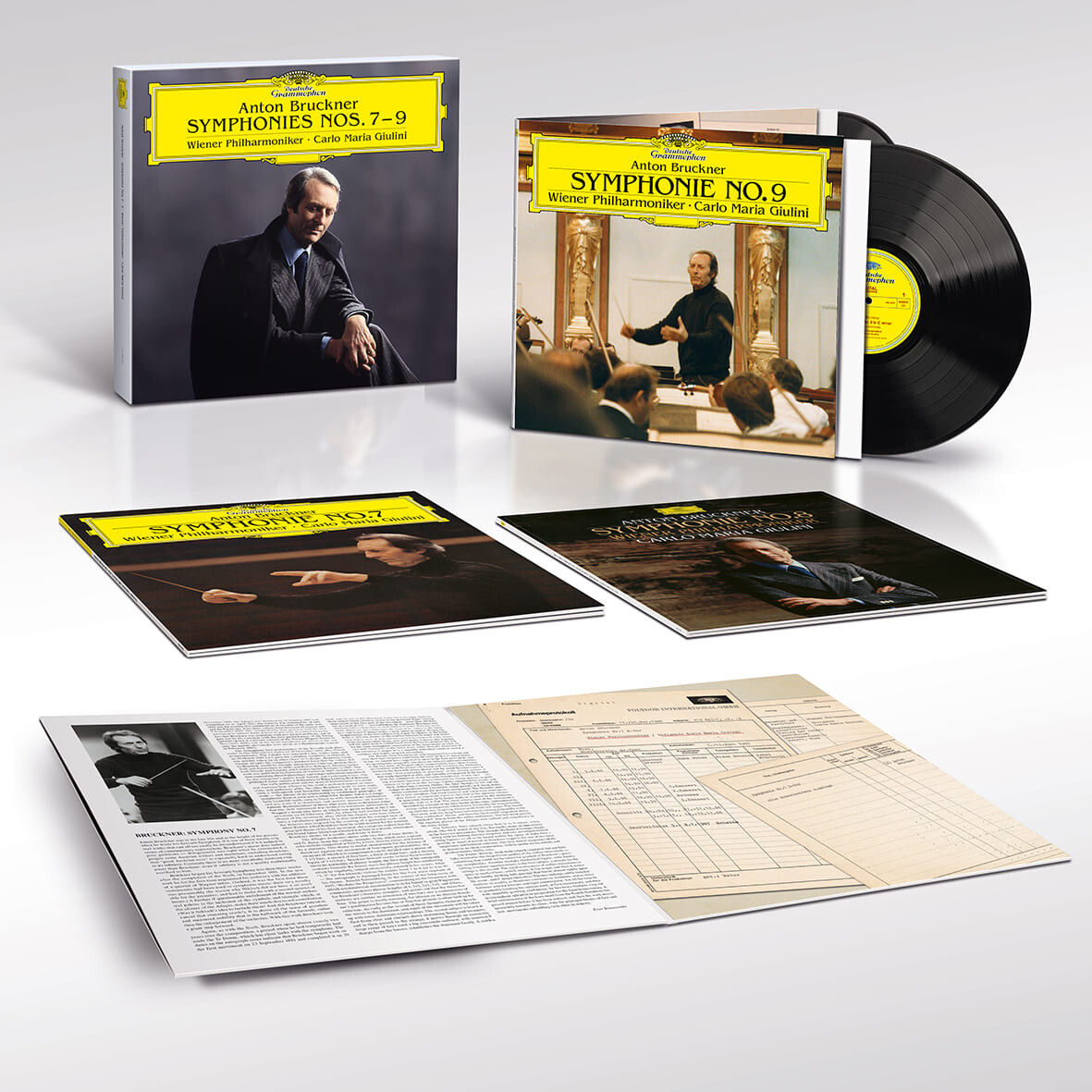

Excellent sleeve notes (which look like they are brand new), and the usual additional photos of session documents grace the gatefold editions of each symphony. All three double LP sets come within the same kind of sturdy slip-case that encompassed the William Steinberg/BSO Original Source LPs. Covers are presented with matte finishes. It’s a handsome package - but also a limited edition. If this is anything like the Original Source releases, it will sell out pretty quickly, so if you're interested do not delay.

This is an essential purchase for anyone remotely into large-scale orchestral music - or anyone simply curious as to what the Bruckner fuss is all about.

Or anyone else who wants to see if they can blow up their systems! (Yes, you can - just keep cranking that volume knob, which you will be very tempted to do.)

For those of us waiting with bated breath for the August release of Karajan’s complete Bruckner cycle from DG and EBS, this set is far more than a mere place-holder. For these last three symphonies, it’s going to offer the Big K and the BPO some serious competition.

Anton Bruckner: Symphonies Nos. 7, 8 and 9

Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra

Carlo Maria Giulini, conductor

Symphony 7:

Recording: Grosser Saal, Musikverein, Vienna 6/1986

Production: Gunther Breest

Recording Supervision: Hans Weber

Balance Engineer: Klaus Scheibe

Symphony 8:

Recording: Grosser Saal, Musikverein, Vienna 5/1984

Production: Gunther Breest

Recording Supervision: Hans Weber

Balance Engineer: Klaus Scheibe

Symphony 9:

Recording: Grosser Saal, Musikverein, Vienna 6/1988

Production: Gunther Breest

Recording Producer: Hans Weber

Balance Engineer: Klaus Hiemann

Editing: Reinhold Schmidt, Andrew Wedman

Reissue:

Mastered and Cut at Half-Speed by Rainer Maiilard and Sidney C. Meyer at Emil Berliner Studios

Product Managers: Meike Leiser, Johannes Gleim

Pressed at Optimal

Limited Edition of 1700

MUSIC: 11

SOUND: 8/9

.png)