Britten’s WAR REQUIEM Revisited - A Masterpiece Newly Relevant - PART 3: Restoration and Remastering, plus Review

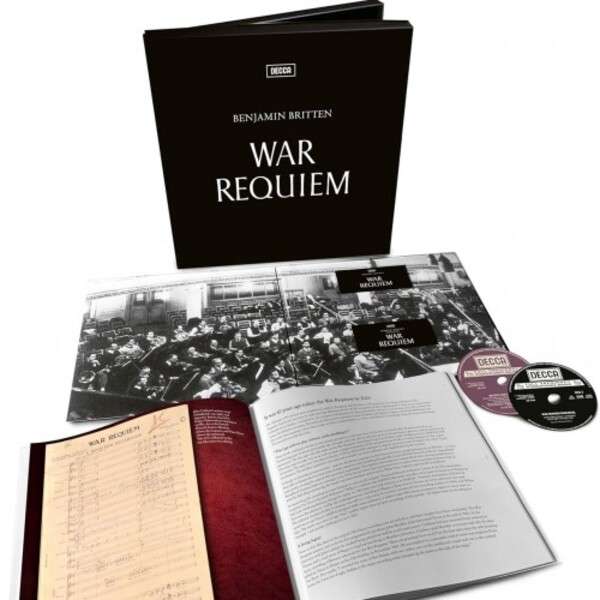

Decca's 60th Anniversary Re-Release of one of the catalogue's greatest achievements prompts a re-examination of this profound anti-War statement

The 2023 Restoration and Remastering

Britten’s War Requiem had been through numerous vinyl and CD editions over the years. However, as with Decca’s reissue of the Solti Ring Cycle I reviewed on this site last year, this is the first time in many years that the recording has undergone a fully-fledged, back-to-the-master tapes restoration and remastering.

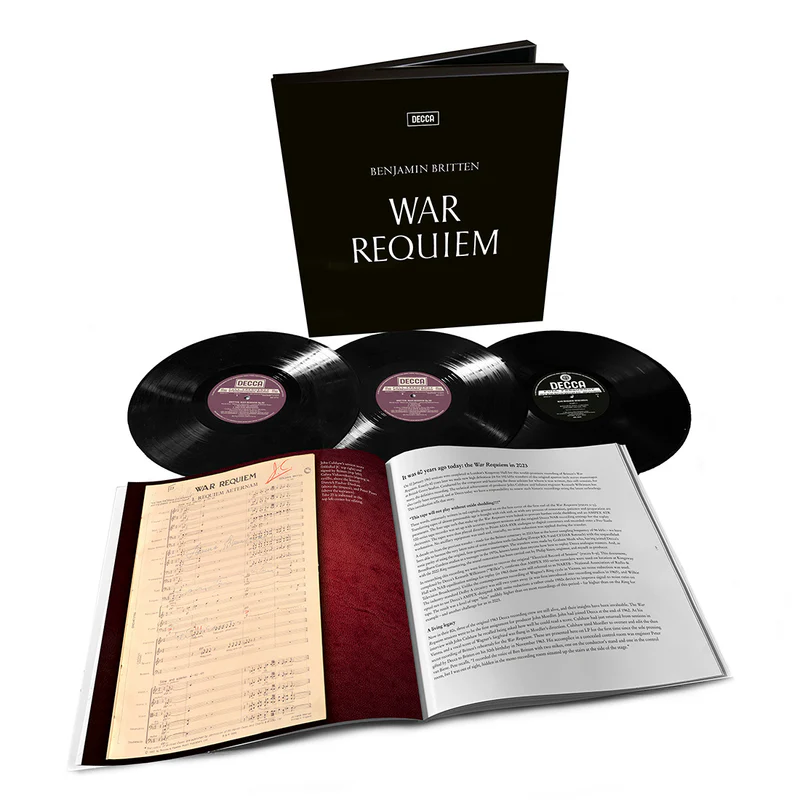

The reissues exist in two physical forms. One is a dual-layer CD/SACD box, one is a 3LP vinyl edition (there is an additional downloadable Dolby Atmos mix). All are derived from digital masters from the restored master tapes. The vinyl is cut - as was the Solti Ring - by Miles Showell at Abbey Road using his usual half-speed mastering process.

Both editions come in identical looking 12” LP format box sets, a great decision since it means that the accompanying booklet is printed full size for both formats.

That booklet is gorgeous to look at, to hold, and a rewarding adjunct to the music - full to the brim with extensive notes, text and hitherto unseen photos of tapes, scores, documents, sessions etc. to delight and surprise the Britten enthusiast. Kudos to Decca for not skimping on giving us all the archive goodies here. I wish other labels would do the same on such reissues. The pages of the booklet from the original 1963 vinyl release are also included, all in original type and layout, at the end of the new booklet. A fine color photo of Britten graces the cover.

The rehearsal sequence secretly recorded and edited as a 50th birthday present for the composer is included as an extra LP in the vinyl set, and as an extra disc in the CD/SACD set.

To celebrate these reissues, Decca produced an excellent short promotional video, full of relevant information. You will get to see Britten's own record player (a Garrard) in action in the living-room of his longtime home in Aldburgh, The Red House.

The reissue booklet kicks off with an excellent and highly informative account by the reissue producer Dominic Fyfe, some of which I have already quoted from in my account of the recording sessions here. Clearly no effort was spared to do right by this historic recording, one of the most important in the Decca catalogue.

Rather than attempt my own summary, here are extracts from what Fyfe has to say about the restoration process:

‘THIS TAPE WILL NOT PLAY WITHOUT OXIDE SHEDDING!!!

‘These words, ominously written in red capitals, greeted us on the box cover of the first reel of the War Requiem. Transferring tapes of almost pensionable age is fraught with risk and, as with any process of restoration, patience and preparation are paramount. The four tape reels that make up the War Requiem were baked to prevent further oxide shedding and an AMPEX ATR 100-series tape recorder was set up with accurate transport tensions and the original Decca NAB recording settings for the replay electronics. The tapes were then played directly to Prism ADA-8XR analogue to digital converters and recorded onto a Pro-Tools workstation. No ancillary equipment was used and, crucially, no noise reduction was applied during the transfer.

‘A decade on from the previous transfer - made for the Britten centenary in 2013 but at the lower sampling frequency of 96 kHz - we have been able to harness the very latest suite of noise reduction tools (including iZotope RX-9 and CEDAR Retouch) with the unparalleled sonic purity of using the original, first-generation master tapes. The transfers were made by Graham Meek who, having joined Decca’s Broadhurst Gardens studios as a teenager in the 1970s, knows better than anyone how best to replay Decca analogue masters. And, as with the 2022 Ring remastering, the sound restoration has been carried out by Philip Siney, engineer, and myself as producer.

‘In researching this recording we were fortunate to recover the original “Electrical Record of Session” (pictured in the booklet). This document, completed by Decca’s Kenneth Wilkinson (“Wilkie”), confirms that AMPEX 350-series recorders were used on location at Kingsway Hall with NAB equalisation settings for replay (in 1963 these were still referred to as NARTB - National Association of Radio and Television Broadcasters). Unlike the contemporaneous recording of Wagner’s Ring cycle in Vienna, no noise reduction was used. The industry-standard Dolby A circuitry was still two years away (it was first introduced into recording studios in 1965), and Wilkie opted not to use Decca’s AMPEX-designed AME noise reduction: a rather crude 1950s device to improve signal to noise ratio on tape. The result was a level of tape “hiss” audibly higher than on most recordings of the period - far higher than on the Ring for example - and another challenge for us in 2023.

‘In 2019 this classic recording was inducted into the Washington Library of Congress National Recording Registry alongside Pablo Casals’ Bach ‘Cello Suites and the speech given by Robert Kennedy on the assassination of Martin Luther King. All are united by being deemed culturally, historically or aesthetically significant. Britten’s achievement - and that of Decca - is all of these. A musical and technical triumph for the ages.’

The Sound

This has always been one of the most sonically powerful and demanding records in my collection. Any work that veers between massed choirs and full orchestra playing at full tilt with intimate vocal performances accompanies by chamber instrumental forces is going to put any system through its paces. While so many of his other recordings rightfully sit at the pinnacle of achievement in terms of recorded sound, the War Requiem remains in a class of its own in the discography of the legendary Kenneth Wilkinson.

The work begins with soft tam-tam, low percussion, and strings in octaves beginning their heavy tread, a slow-moving march (through mud and corpses) that pervades this opening. With tubular bells ominously tolling the tritone interval - the “devil in music” - whose dissonance pervades the score, the large choir enters in hushed tones, intoning the words “Requiem aeternam” - “Let Them Rest in Peace”.

Building to a climax on the words “et lux perpetua luceat eis” (“let eternal light shine upon them”) - the irony of which is self-evident in the music that is more tortured than transcendental - the refrain subsides into the first exclamation from the distant boys’ choir: “Te decet hymnus….” (“Thou, O God…. Thou who hearest the prayer, unto Thee shall all flesh come…”).

At which the main choir returns with their lumbering march… “Requiem…” The celestial boys’ chirpy intonations almost feel like a mockery of the trudging humanity below.

This gives way to the first of Wilfred Owen’s poems, sung by the tenor soloist Peter Pears accompanied by glittering harp, chattering strings and wailing woodwind, basses offering us a speeded-up parody of the main orchestra’s opening march figure. Owen’s poem gets right to the point:

What passing bells for these who die as cattle?

Only the monstrous anger of the guns.

Only the stuttering rifles’ rapid rattle

Can patter out their hasty orisons.

Thus, within the first ten minutes, a listener can already get a taste of the many layers and sonic palettes of the work and its recording.

I began my listening with the new vinyl reissue, cut half-speed by Miles Showell at Abbey Road from that new digital transfer and restoration.

First thing I noticed was how dead quiet the 180gram records were (pressed at Optimal, though not indicated as such in the booklet or on the box), with tape hiss inaudible. There was nary a pop or click, even before cleaning.

The work’s three distinct spatial environments emerged clearly, with everything laid out before the listener within the acoustical space of Kingsway Hall. The bass was deeply present. As we shifted to the chamber orchestra and solo tenor, the change in perspective registered and Peter Pears’s voice was clear as a bell in my listening room.

I switched to my original wide-band, ED1 grooved first pressing, one of the original early run of LPs pressed at the time.

I had to contend with some ticks and pops (despite cleaning), noisier surfaces and the clearly audible presence of some tape hiss. However…

I immediately felt what had been lacking in the Showell cut - a connection to the music. Everything somehow felt more organic, less “hi-fi” for want of a better word. These early Decca wide-band pressings were mastered with tubes in the chain, and it makes a difference (as anyone who has compared them with later, transistor-mastered narrow-band pressings will tell you). The instruments and voices simply have the breath of life, and you don’t just get a sense of the hall - you feel the hall.

The differences between the Miles Showell cut and the original wide-band pressing really struck home with the entrance of the chamber orchestra. Suddenly you are hearing - and feeling - that extra level of verisimilitude: the rosin on the strings’ bows, the woodiness of the double-bass, the distinct timbres of the wind and percussion. Then, when Pears starts singing, his voice sounds so much more alive. All these extra overtones are present in a way to make you feel like he is standing right there in front of you.

Now, let me emphasize these differences are not major - they are definitely subtle. Many might not consider them important enough to put up with the extra surface noise etc. inevitable with a 60-plus year-old pressing. However, one difference was inarguable: I simply wanted to go on listening to the original Decca LPs - they drew me in in a way that the reissue did not.

So continue I did, into the Dies Irae movement.

This is where the Latin text lets loose with a vision of the Day of Judgment, and composers like Berlioz and Verdi have a field day with a battery of brass and percussion.

Britten is no exception, but his vision is married to the fact that this is a War Requiem. Again, the music is structured around a crescendoing march, with drums, percussion and brass mimicking the fury of the battlefield and large artillery guns. This Dies Irae is terrifying - a genuine musical vision of hell on earth.

My original Decca pressing unleashed the fury in spades, and you feel the music pushing at the very limits of what Kingsway Hall (and the engineers) can accommodate.

As the music gives way once more to the chamber orchestra, the baritone Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau makes his first appearance with Owen’s elegiac evocation of the evening hush after the day of fighting:

Bugles sang, sadd’ning the evening air;

And bugles answer’d, sorrowful to hear…

… The shadow of the morrow weighed on men.

Bugles sang.

Voices of old despondency resigned,

Bowed by the shadow of the morrow, slept.

Fluttering woodwind from the chamber group echo the clarion calls of the brass in the Tuba Mirum, while the solo horn mournfully shadows the singer, likewise echoing the earlier brass calls to judgment. Again, my original pressing delivered a true sense of the musicians sitting right in front of me, with all the subtlest harmonics and overtones of their instruments duly present.

Out of the quiet erupts the soprano soloist, Galina Vishnevskaya - and what a thrilling sound it is - announcing the eternal judgement:

Liber Scriptus:

Lo! The book exactly worded,

wherein all hath been recorded;

thence shall judgment be awarded.

Accompanied only by declamatory wind in the main orchestra, her voice seems to fill the entire hall: sharp, clear, piercing, a true manifestation of the Almighty’s judgment.

This gives way to the chorus pleading for forgiveness while the soprano continues her pronouncements:

What shall I, frail man, be pleading?

Who for me be interceding,

when the just are mercy needing?

It was time to turn to the remastered CD/SACD, mastered by Ian Watson. After briefly sampling the CD layer, I focused on the SACD layer, and went back to the beginning of the work.

From the very opening I was riveted by the clarity and presence of the recording. No tape hiss, no noise, just an arresting representation of every facet of the master tape. Everything emerged so clearly, with dynamic contrasts and orchestral and spatial information enhanced. Compared to the reissue vinyl pressing, it was if a very, very thin layer of transparent silk had been removed. The chamber group and male soloists were revealed in even finer detail

Once we got into the Dies Irae the brass and percussion bit like ravenous dogs, and when Vishnevskaya intoned her massive Liber Scriptus you felt the windows shaking.

The detail and power in the presentation was addictive in itself. And yet…

At a certain point I found myself missing the warmth and organic flow of my original Decca pressing. It just has that certain je ne sais quoi…

Two sections of the War Requiem will put your system through the ultimate test, the Sanctus and Libera Me.

The Sanctus opens with loud, peeling bells and piano, against which the soprano soloist declares the glory of God. On the CD/SACD the sharp transients and decays of the bells were crystal clear, utterly riveting. All kinds of jangly goodness!! Boy does this sound not only like Stravinsky’s Les Noces (scored for multiple pianos, percussion, and women’s voices), but also Pierre Boulez’s Sur Incises for similar instrumental forces. (The traditionalist Benjamin Britten anticipating the arch modernist Pierre Boulez by decades? How delicious is that!)

Then out of silence the chorus emerges pianissimo, whispering and chanting freely the words Pleni sunt coeli (“Heaven and earth are full of thy glory”). Britten is using a technique here which anticipates what Penderecki does in his St. Luke Passion of three years later. Let no one accuse Britten of being a “traditional, old-fashioned composer”. Listening to the War Requiem again I was struck anew by how incredibly modern, even experimental he could be, albeit within a traditional tonal framework. Echoes of Bartok, Stravinsky, Shostakovich suffuse this music, but Britten’s voice emerges with its own distinct personality.

The chorus builds to a frenzied outpouring of praise, with whooping and wailing brass and thumping drums at full tilt.

There follows the alternately raging and eerie, post-apocalyptic vision of the earth after war has destroyed all: "After the blast of lightning from the east...", sung by the baritone solo, which ends thus:

And when I hearken to the Earth, she saith:

'My fiery heart shrinks, aching. It is death.

Mine ancient scars shall not be glorified,

Nor my titanic tears, the seas, be dried.'

Throughout the recording of the War Requiem you will be treated to spectacular renderings of every detail of Britten’s percussion section, and this comes across especially vividly on the CD/SACD. For example, sample the fierce drums mimicking the sound of the huge artillery that pounded the trenches in “Be slowly lifted up, thou long black arm/Great gun towering t’ward Heaven, about to curse…”, sung with spine-tingling intensity by Fischer-Dieskau, leading back into a reprise of the Dies Irae.

On to the Libera Me, the culmination of all the strands in the work. Once more the Latin text’s plea for deliverance is framed as a limping march through mud and death - halting, painful. The march builds to frantic cries: "I am in fear and trembling…”

The cataclysmic cadences of the Dies Irae return, smiting down humanity as it begs for forgiveness. It’s as if all the armaments of the battlefield are being brought to bear on crushing the human spirit. In one final desperate, rallying effort the chorus attempts to break free, only to be swept aside in a massive triple fortissimo change of key, fortified by a huge tam-tam crash. The chorus is defeated and retreats once more into its defeated, limping march, then fades away completely.

Every time I hear this moment in the work I get chills running down my spine. It is that visceral. It is the moment by which I judge every recording of the War Requiem, and every one I have heard I have found wanting in comparison to this Decca recording, which nails it. You feel like the whole building might collapse, it is so powerful. The tape is definitely hovering at the point of maximum saturation.

This section is featured in my discussion of this recording from my YouTube channel, accompanied by visuals derived from WWI and WWII artists. The sequence begins at 24:30.

The CD/SACD fully accommodates the moment, and hits you with tremendous force. The original pressing is no slouch either, though it may lack that last extra “whoomph” present on the SACD layer. The Miles Showell cut is hardly lacking, though again there is just this nagging sense that something is missing.

The music gives way to the setting of Wilfred Owen’s poem “Strange Meeting”, in which one soldier meets the other soldier he just killed. The music is quiet, still, and profoundly unsettling, with string writing that has much in common with Shostakovich’s haunted string quartets. While the detail and verisimilitude on the SACD is compelling in its own right, it is the original Decca pressing that gets closest to the heart of this passage. You feel as well as hear every bone chilling moment.

This gives way to the final quasi-benediction at the end of the work, in which for the first time all the forces sing together.

"Let us sleep now" declare the two soldiers, while the boys' choir intones the In Paradisum. The full choir and soprano soloist join with their plea for ascension to Paradise. As the plea subsides the tolling tritone bells return, and the chorus sings a final muted "May they rest in peace. Amen".

The work resolves onto a final major chord, but this ending is equivocal at best. As Peter Pears once described it: “It isn’t the end, we haven’t escaped, we must still think about it, we are not allowed to end in a peaceful dream.”

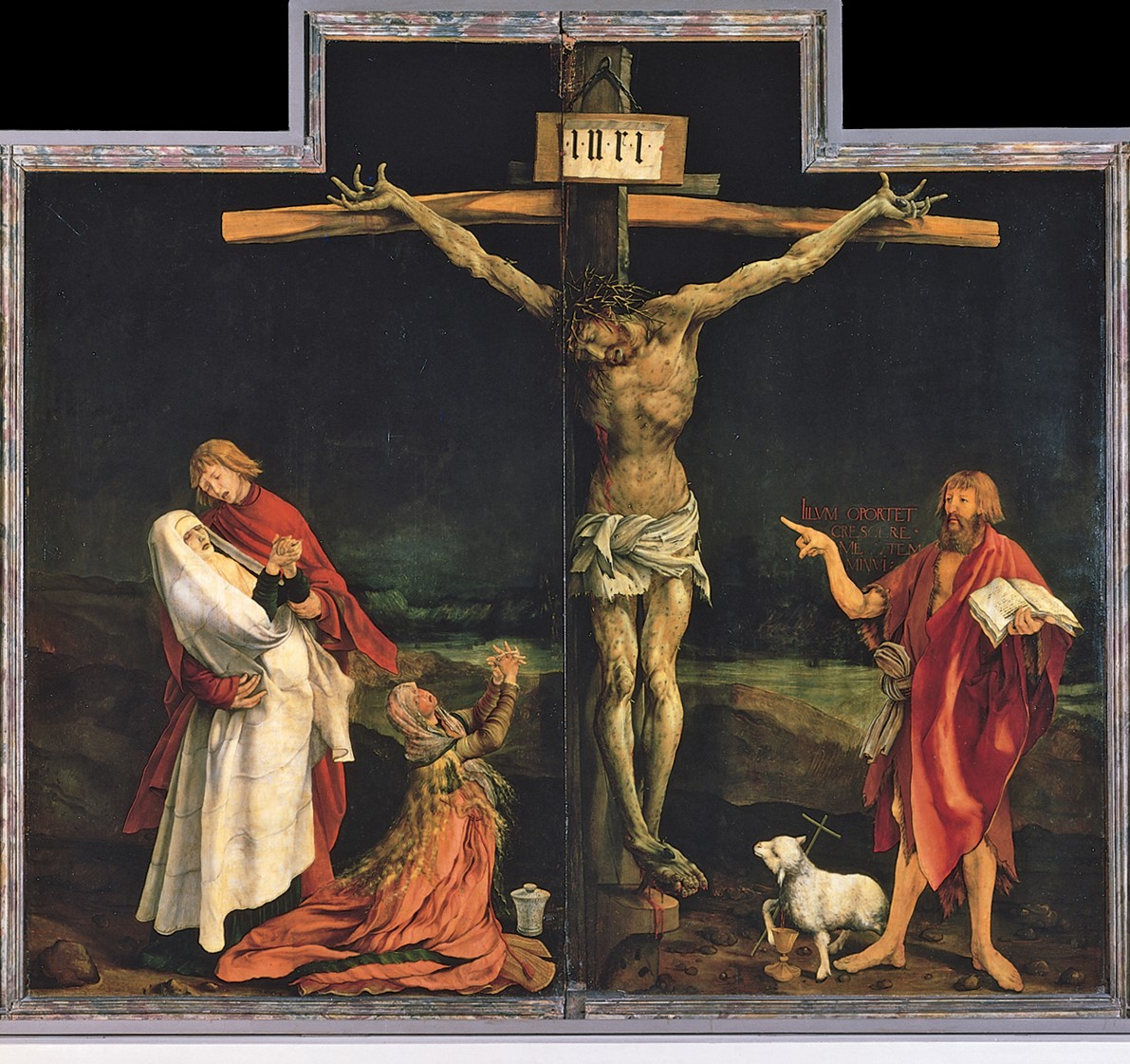

The Resurrection panel from Matthias Grünewald's Isenheim Altarpiece (1512-1516), one of Britten's visual influences when composing the War Requiem

The Resurrection panel from Matthias Grünewald's Isenheim Altarpiece (1512-1516), one of Britten's visual influences when composing the War Requiem

Conclusions

So what is a potential buyer of the War Requiem to do? For the most emotionally involving listen there is no question that an original Decca wide-band pressing is the way to go, provided you accept there will be some surface noise and greater tape hiss. You will lose none of the fidelity of the recording, and will marvel anew at how a record this old can sound this good. Used copies will not break the bank - indeed they might be cheaper than buying the new reissues.

You can also go for an original London wide-band pressing, so long as it is made in England (very important - it will show this on the record label).

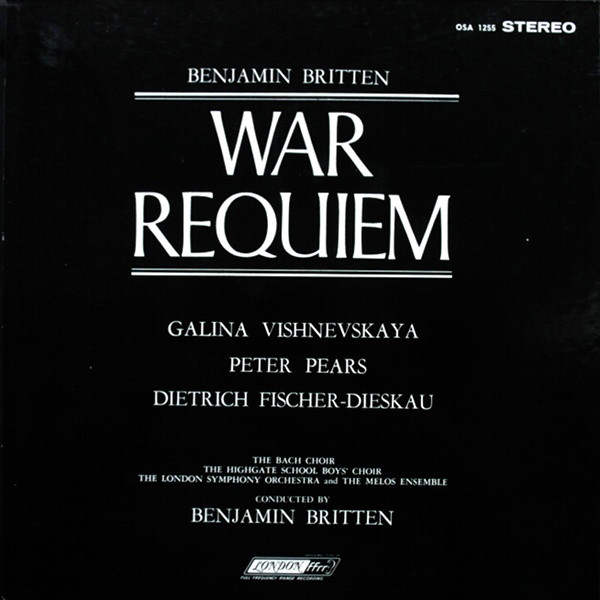

The London Records edition of War Requiem: note the change in the album artwork in order to promote the performers, thus undercutting the impact of the original minimalist design

The London Records edition of War Requiem: note the change in the album artwork in order to promote the performers, thus undercutting the impact of the original minimalist design

However, I believe all these early copies were cut auto-coupled for record changers, so you will have to flip the records more often. In the booklet notes drawn from his autobiography, Culshaw reveals the problems they had with the factories not initially pressing enough records, and how that impacted the American market:

Culshaw:

‘… the managing director was responsible for deciding how many records should be manufactured on the first run of any new release. This was often easy and predictable: for example, any new record by Clifford Curzon would be bound to sell a known quantity, and if it created a demand for a lot more the trend would not show for several weeks, which gave time for the factory to be alerted. (I should mention, incidentally, that at that period and for some years to come Decca in London pressed records not only for the home market, but also for the United States where they were exported in bulk). The expectations for the War Requiem were high and the reviews, based on advance-of-release copies were ecstatic. But the initial pressing order put through to the factory was for a few hundred sets, which were immediately grabbed by the home market. There were loud protests from New York, upon which a few hundred more were run off and shipped: they did not cover even a tiny fraction of the orders.

‘By then, however, a pop LP had monopolized the presses at the factory, and the “run” could not be disturbed to press orders for the Requiem, which, within two weeks of its release, was unobtainable on either side of the Atlantic. The Americans, rightly sensing a classical hit, notified London they could wait no longer and began making their own pressings from master plates imported from London. Fortunately they also decided to make their own albums (albeit with altered art work, alas - MW), for the very moment that it became possible to press more copies for the home market the art director announced an indefinite hold-up in the production of boxes, which meant that before long the factory was clogged with unboxed (and therefore vulnerable to dust and damage) records of the Requiem…’

The SACD layer of the new CD/SACD is a model of how well a restoration can sound, and this reissue is a mandatory purchase for any devotee of the work (as was the newly remastered SACD of Solti's Wagner Ring cycle). (Also available is a download of a Dolby Atmos mix for the surround sound aficionados amongst you. I have not heard this).

Along with the fabulous booklet and the Britten rehearsal, you will hear a rendering of the master tape that takes you right into the recording sessions. It is thrilling. The CD layer is easily the best-sounding CD version of this recording issued so far.

However, at some point you might find yourself yearning for the more organic experience of the original Decca or London (UK-made) LPs.

As to the new Miles Showell cut, there’s nothing wrong with it, and many will be perfectly happy to have a dead silent pressing of the restored master tape. However, something is missing. I do not think this is simply a matter of cutting from a digital rather than an analogue source. The same shortcomings plagued Showell’s cut of the restored Solti Ring cycle. I wonder what would have happened if, for example, the team at Emil Berliner Studios (responsible for the amazing DG Original Source records) had done the vinyl cut. Their cuts from digital sources, sometimes using half-speed mastering, have been exemplary.

I am not alone in finding Miles Showell’s vinyl masterings lacking: in the pop realm his editions have received very mixed reviews.

I think it’s time for Decca to look elsewhere when it comes to cutting fresh vinyl editions of its back catalogue. There are a slew of fine mastering and cutting engineers who have more than demonstrated their ability to produce outstanding classical reissues, whether cut from analogue or digital - along with EBS, I will mention Ryan K. Smith and Kevin Gray. It seems such a shame to put so much effort into these reissues, only to have the vinyl version come up somewhat short when maybe it didn’t need to.

However, like I said, many will be perfectly happy with the new vinyl edition - it’s maybe just vinyl and classical obsessives like me who will hear the differences. After decades of collecting, comparing pressings etc., you cannot escape the fact that those early Decca (and UK-made London) pressings are sprinkled with fairy dust. They are indeed magical, something beyond a technological triumph, and only the best will do for one of the genuine masterpieces not only of the 20th century classical repertoire, but also of the entire catalogue of recorded music.

The War Requiem Then - and Now

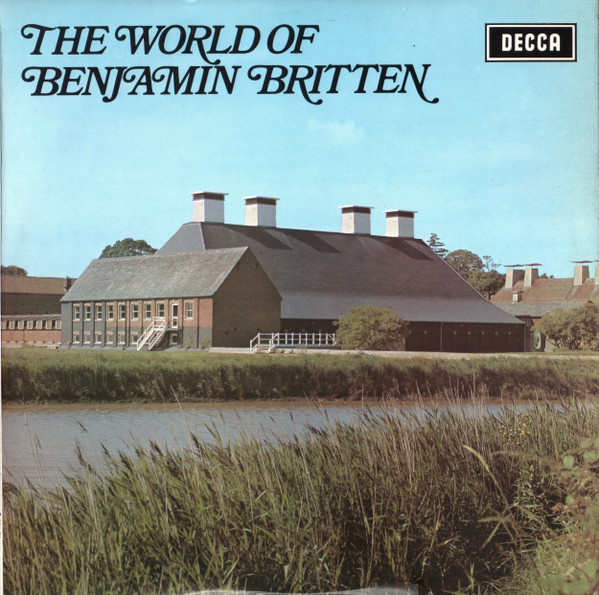

I discovered the War Requiem when I was a mere lad (as they say). Having sung some of Britten’s music in choir, I also knew The Young Person’s Guide to the Orchestra. With my hard-earned, grass-cutting pocket money, I bought this excellent collection Decca put out on its budget label.

The extracts from the War Requiem contained therein, which included the Sanctus discussed above, were amongst the most compelling music on the record, and as soon as I could I bought a copy of what was then the in-print vinyl edition of the complete work, a narrow-band pressing (which, alas, I could not find for this review - it sounds excellent, but go for the earlier, tube-cut wide-band edition). So, in a very real sense, I have lived with this work my whole life.

Listening to those LPs all those years ago made a huge impression, and I suspect on some level changed my consciousness. If you've never heard the War Requiem, listening to this recording might well do the same for you.

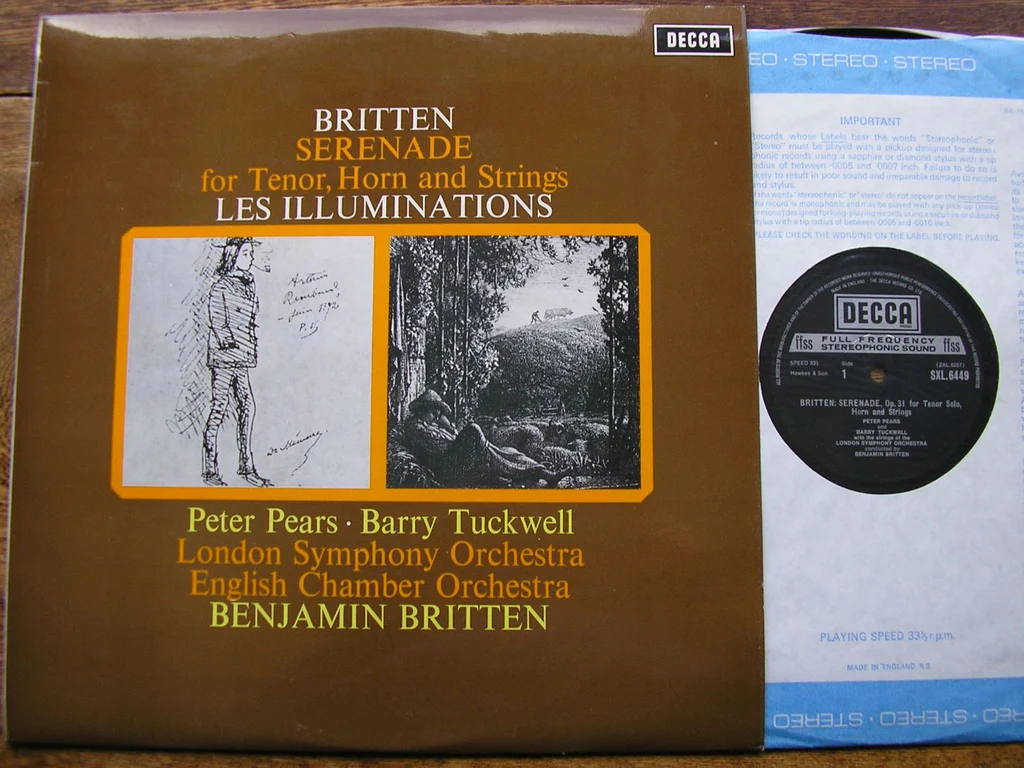

Through this piece I was introduced me to the extraordinary poetry of Wilfred Owen, and also to those two amazing singers, Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau and Galina Vishnevskaya, both legends in their own lifetimes, and whose records I subsequently collected. I already had several of the Britten-Pears collaborations in my library. most notably this LP of his two great song cycles with orchestra.

(The original wide-band releases of both song cycles have different couplings - they sound incredible.)

I rarely listen to the War Requiem now, but I know it very well. It is definitely a part of my being. It is not a work anyone would listen to often apart from when they are first learning it - or returning to it "when in the mood". It is too gut-wrenching an experience. Listening to this recording, or attending a live performance, will leave you changed in ways that few works of art are capable of achieving, even the greatest of them. You will peer into the abyss and fully feel the horror that awaits all of us should humanity fall once more into pervasive all-out war across the globe.

Which, right now, it shows every sign of doing.

Listening to the War Requiem again for this review was to be reminded of how unique a work it is in the history of music. There is no other that so fully addresses the many aspects of what war is, what it is like to experience it, how it degrades our humanity, how it threatens existence itself. You will feel the futility of it all, especially now, and ask the question: “Are we truly no better than this?”

But in Britten’s music there lurks another strand: the composer’s overwhelming sense of pity, compassion and humanity - an intense need to find something more, something beyond the multitudinous negatives in the world. There is tenderness, remorse, an aspiration to overcome, to find something better. And above all there is a sense of the possibility of connection, of communication amidst all the destruction. If, like the two enemy soldiers in Strange Meeting, we can finally talk to each other, find solace in each other, is there not some hope?

The strength, beauty and power of the music itself, even at its most caustic, is also a harbinger of that hope.

The Decca recording of Britten’s War Requiem is something substantially more than the sum of its considerable parts: it is living history, and a clarion call, a warning shot fired across the bow of humanity. Listening to this work, this recording, only underlines the peril of the present moment in which the world currently finds itself.

We ignore the warning of the War Requiem at our peril.

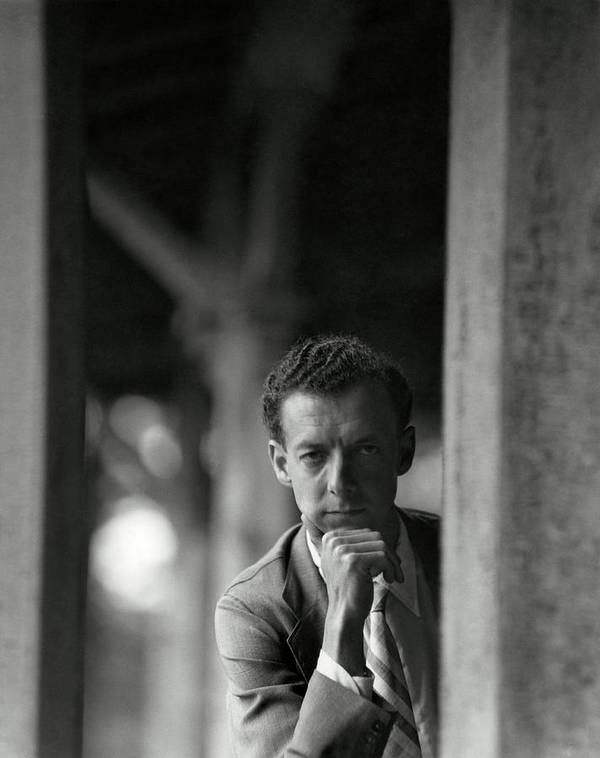

Portrait of Benjamin Britten (1946, by Frances McLaughlin-Gill)

Portrait of Benjamin Britten (1946, by Frances McLaughlin-Gill)

You can read Part 1 of this survey of the War Requiem here, and Part 2 here.

For anyone wanting to explore more of Britten's music, and what made him such a compelling musician as well as composer, I highly recommend this documentary about his relationship with the BBC. It is full of amazing footage, insightful commentary from those who knew him, and insights into his work and life. The section relating to the War Requiem begins at 21:24

Benjamin Britten: War Requiem

Galina Vishnevskaya, soprano

Peter Pears, tenor

Dietrich Fisher-Dieskau, baritone

The Bach Choir and the London Symphony Orchestra Chorus (David Willcocks, chorus master)

Highgate School Choir (Edward Chapman, director of music)

Simon Preston, organist

Melos Ensemble

London Symphony Orchestra

conducted by

Benjamin Britten

John Culshaw, recording producer

Kenneth Wilkinson, recording engineer

Recorded by Decca in Kingsway Hall, London, on January 3-5, 6-8, and 10, 1963

Additional 1963 Credits:

Michael Mailes, location engineer

Rehearsal recording supervised by John Mordler and engineered by Peter van Biene

2023 Remastering:

Reissue Producer: Dominic Fyfe

Remastering Engineer: Philip Siney

Tape Research: Jason Repantis

Tape Transfer: Graham Meek (British Grove Studios)

Half-speed Vinyl Mastering: Miles Showell (Abbey Road Studios)

SACD Mastering: Ian Watson

Product Management: Jade Powell

2023 Remastering Reissued as 485 3765 (2 CD/SACD); 485 3769 (3 LP)

MUSIC: 11

SOUND: 10 (SACD) 8/9 (LP)

.png)