History Etched on Vinyl: Wilhelm Furtwängler and the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra - The Radio Recordings (1939 - 1945) PART 1

The In-House Label of the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra presents a Compelling Survey of the Legendary Conductor at work in Wartime Germany

When it comes to “Big Names” in the Pantheon of “Great Conductors”, there is one name that towers over all others, carved into the granite of classical music’s Mount Rushmore.

Wilhelm Furtwängler.

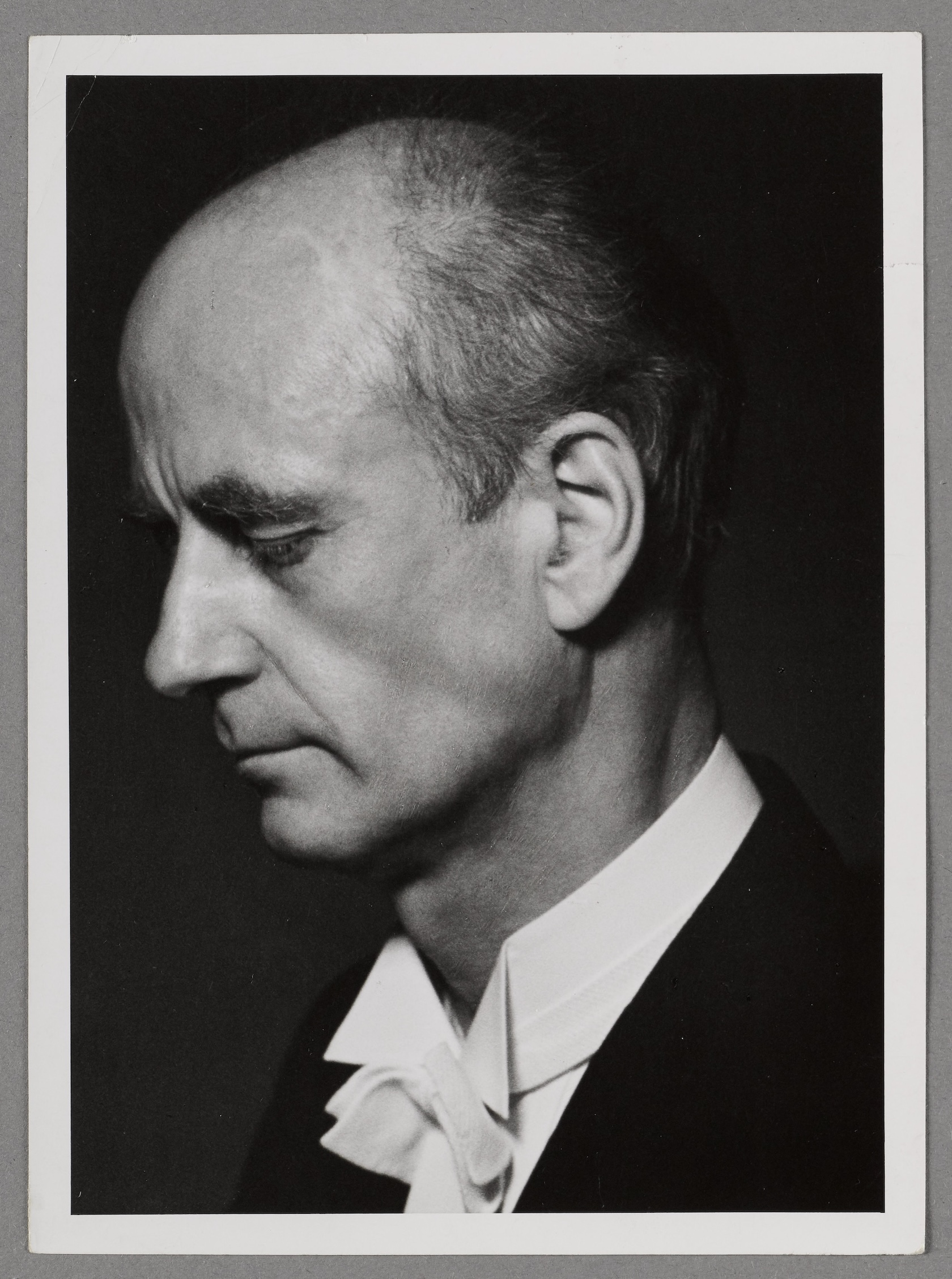

Wilhelm Furtwängler (photo by Hilde Zenker)

Wilhelm Furtwängler (photo by Hilde Zenker)

The name says it all: Teutonic, authoritative, demanding of effort to say it correctly - even the umlaut on the “a” feels like it demands reverence. (Without that umlaut the surname feels like it could morph into something far less dignified…)

Indeed, Furtwängler is a figure who is taken SO seriously in some quarters (and he took himself VERY seriously indeed) that he is practically begging to be taken down a peg or two.

Anyone who is coming to classical music anew will have that moment when Furtwängler’s name first comes up, and they will no doubt be a little mystified at the hush tones of awe that descend upon those talking about him. Those people, those classical music folks “in the know” - it’s like they’re talking about God. No really! I’m not exaggerating. Furtwängler’s recordings, mostly dismal sounding missives from long before even the pre-HiFi days, are received by the faithful like the inviolate Word of Jehovah descending from the Mount, inscribed on stone tablets.

The classical music world is pretty good at fostering cults around certain performers, even whole genres (eg. opera). The great Argentinian pianist Martha Argerich, for example, is probably the living artist with the most rabid following, verging on the cult-like. But how about Maria Callas, Enrico Caruso, Luciano Pavarotti amongst deceased singers; Michael Raban, Jascha Heifetz amongst violinists; Toscanini, Leonard Bernstein and Herbert von Karajan amongst conductors…?

But in the cult stakes no-one compares to Furtwängler in terms of the almost religious zealotry with which his massive recorded legacy of live and studio performances (again, in mostly dismal sound) is pored over, scrutinized, analyzed, proselytized for - and against. Beethoven’s “Eroica” Symphony? Are you going for the version from 1944, 1947, 1950 (June or August), 1952 (Rome, Vienna or Berlin - with multiple dates for each), 1953 - August with the Lucerne Festival Orchestra, or September with the Vienna Philharmonic?

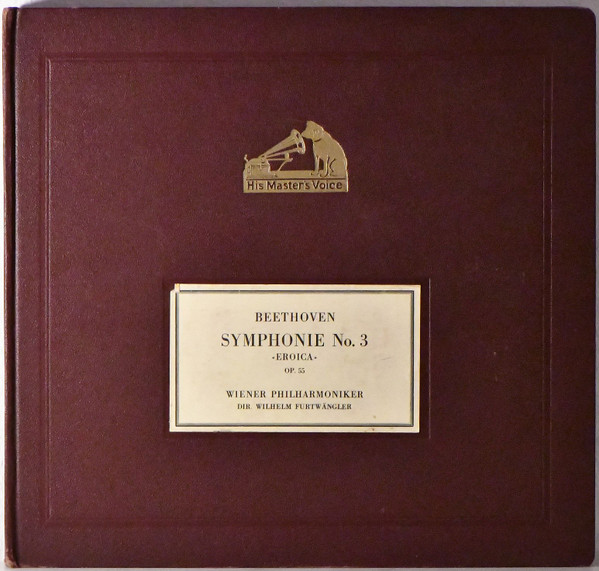

Furtwängler's 1947 Recording of Beethoven's "Eroica" Symphony on 6 Shellac 78rpm Records

Furtwängler's 1947 Recording of Beethoven's "Eroica" Symphony on 6 Shellac 78rpm Records

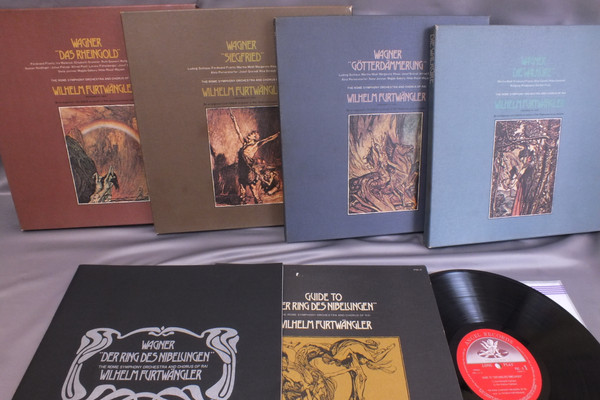

Wagner’s Complete Ring cycle: live at La Scala in 1950, or Rome in 1953 in the studio for radio?

Japanese Edition of Furtwängler's 1953 Rome "Ring" Cycle

Japanese Edition of Furtwängler's 1953 Rome "Ring" Cycle

Furtwängler obsessives will know them all, have detailed opinions about them all, will collect every last recorded edition, both official and bootlegged. And there are many Furtwängler obsessives, let alone all the more casual collectors who will nevertheless know an awful lot about the conductor’s discography, and own much of it.

So what’s all the ballyhoo about? Is it real? Was he really the greatest conductor who ever lived? (No). Is he worth looking into? (Yes). Even when the sound of his recordings is so dodgy? (I think so).

Where to begin?

Read on.

THE FURTWÄNGLER PHENOMENON

Now I’m not going to even vaguely pretend that I am a Furtwängler expert in any way, shape or form. But in many ways that makes me the ideal guide for you - the curious Tracking Angle listener. I’m coming at Furtwängler from very much the same vantage point that you are.

What is it that makes Furtwängler so special? He has a way of burrowing into the core of the music, especially the masterpieces of the later German tradition (Beethoven, Brahms, Wagner, Bruckner), of communicating the deep eddies and flows of the music in a manner that seems illuminated from within. While his control of ensemble is sometimes shaky, his control of pulse is extraordinary, allowing him to speed up and slow down in a manner that can make the listener feel like they are rafting from a gently flowing river to rapids and back again within a heartbeat. And it rarely feels like these tempo changes aren’t in the score (they often aren’t). It’s a subjective approach, where communicating the spiritual intent of the music is paramount. It is the complete opposite of Toscanini, father of the new objectivism in music interpretation, which finds perhaps its ultimate expression in today’s period instrument movement.

Bayreuth, 1931: Furtwängler (seated l.) with Winifred Wagner (c.) and Toscanini (seated r.)

Bayreuth, 1931: Furtwängler (seated l.) with Winifred Wagner (c.) and Toscanini (seated r.)

Make no mistake, when a Furtwängler performance is hitting its marks, one is hearing something utterly unique and compelling (of which there are several examples on these records under review). The moments of catharsis, when he summons forth seemingly limitless reserves of power and force from deep within the belly of the orchestral beast, are unlike anything I’ve heard from any other conductor. This isn’t simply a matter of playing loudly; it’s a matter of having subsumed not only all the tangible elements of form, dynamics, pulse, harmony, counterpoint etc, but also the intangible elements - the spiritual energy - in such a way that the inner life of the music emerges with the force of a primal scream.

Furtwängler is pretty much sui generis when it comes to conductors following his approach to music making. Certainly there have been those like Daniel Barenboim and Christian Thielemann who have aspired to something like the Furtwängler approach and effect, but they are not in the same league. Thielemann in particular comes off mainly as a pretender to the throne, all weird tempi and off-putting mannerisms, with none of that core integrity which distinguishes The Master.

I’m not going to get into too much detail about Furtwängler’s complex relationship with the Nazi regime, in part because I simply do not have the knowledge to pass meaningful judgment, but suffice it to say that the conductor’s own often expressed thoughts upon the inherent superiority of the German musical heritage vibed with Nazi orthodoxy, and he worked with the explicit approval and support of the regime, even when he transgressed his fealty.

Furtwängler with Hitler

Furtwängler with Hitler

The conductor’s statement in 1947 that: “a single performance of a truly great German musical composition was by its nature a more powerful, more essential negation of the spirit of Buchenwald and Auschwitz than all words could be” sounds a mite disingenuous given the history of what went before. (I will say, though, that the unique circumstances under which these wartime recordings were made lend them a singular urgency and piquancy that stands out within Furtwängler’s catalogue).

Both the Berlin Philharmonic and Furtwängler found themselves in an uneasy alliance with the Nazi party as National Socialism intensified its grip on society, requiring pledges of allegiance etc. (The orchestra, on the verge of bankruptcy and dissolution in the wake of World War I, had necessarily turned to the ascendant Nazi party to maintain its very existence). With the outbreak of war, Joseph Goebbels, Hitler’s propaganda chief, doubled down on promoting Furtwängler and the BPO as chief promulgators of German cultural supremacy, of which the radio broadcasts were a central element. Furtwängler had already knocked heads with the regime, resigning his post over matters of repertoire (the Nazi demand that no Jewish composers be programmed). Despite continuing to conduct the orchestra regularly, and being identified in everyone’s mind as the BPO’s Chief, he didn’t formally take up the official position of Principal Conductor again until after the War. (You can read more about all this here).

So was Furtwängler, determined to keep on working and protect his fellow musicians, a collaborator or a naïve innocent who allowed himself to be manipulated? A bit of both.

Furtwängler was a complicated man living in complicated times, and ultimately he survived the post-War de-Nazification process to conduct another day. He is definitely, like Wagner, the poster child for wondering whether one can divorce the quality of the artist from the failings of the man. Jewish musicians like Daniel Barenboim (also a champion of performing Wagner in Israel) have seen fit to rehabilitate him. Perhaps, at this far remove, one should just primarily consider Furtwängler’s legacy in terms of what one hears, while remaining aware of his shortcomings.

DIVING INTO THE FURTWÄNGLER WATERS

It wasn’t until fairly recently that I decided to finally get to serious grips with the whole Furtwängler phenomenon. Four plus years ago, as we moved into extended lockdown and I had time on my hands, it felt like this was the moment to scratch my Furtwängler itch. I was already somewhat familiar with the various vinyl and CD editions of his recordings. His discography is divided between a relatively small number of studio recordings, mainly on Deutsche Grammophon and EMI, and a plethora of live recordings on a whole host of independent labels in transfers and re-masterings of wildly varying quality. There is an ongoing debate amongst Furtwängler fans and music critics as to whether he is best served by his live or studio recordings. The consensus seems to be that while his studio albums are generally in better sound, his particular brand of music-making - which was highly spontaneous (and also commensurately prone to ragged orchestral discipline - more on this later) and with interpretations of the same work differing enormously from gig to gig - comes across most clearly (and excitingly) in recordings of live performances.

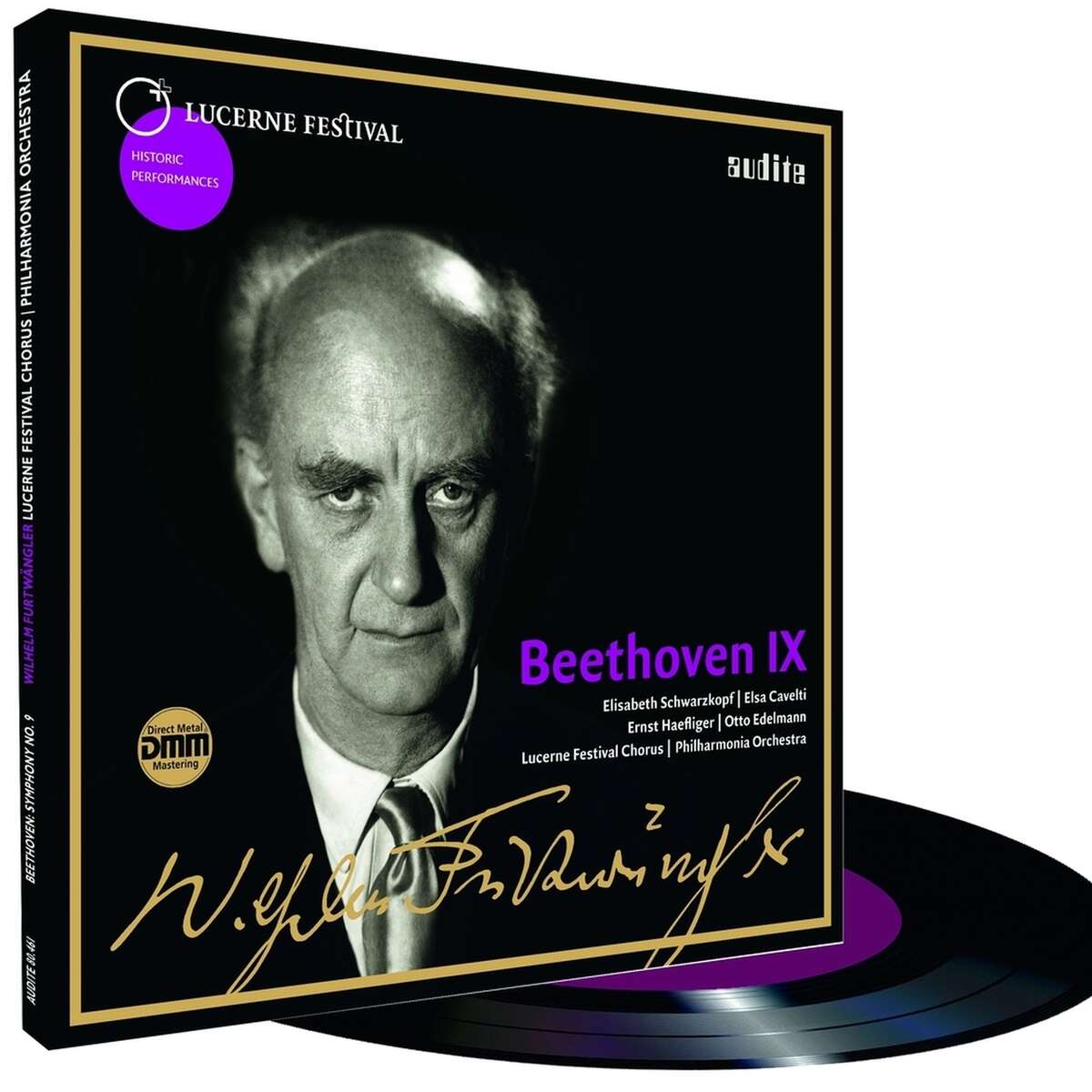

I already had a few isolated Furtwangler CDs (including his marvelous late Beethoven 9th from the Lucerne Festival in 1954, in some of the best sound of his career - it’s now available on LP).

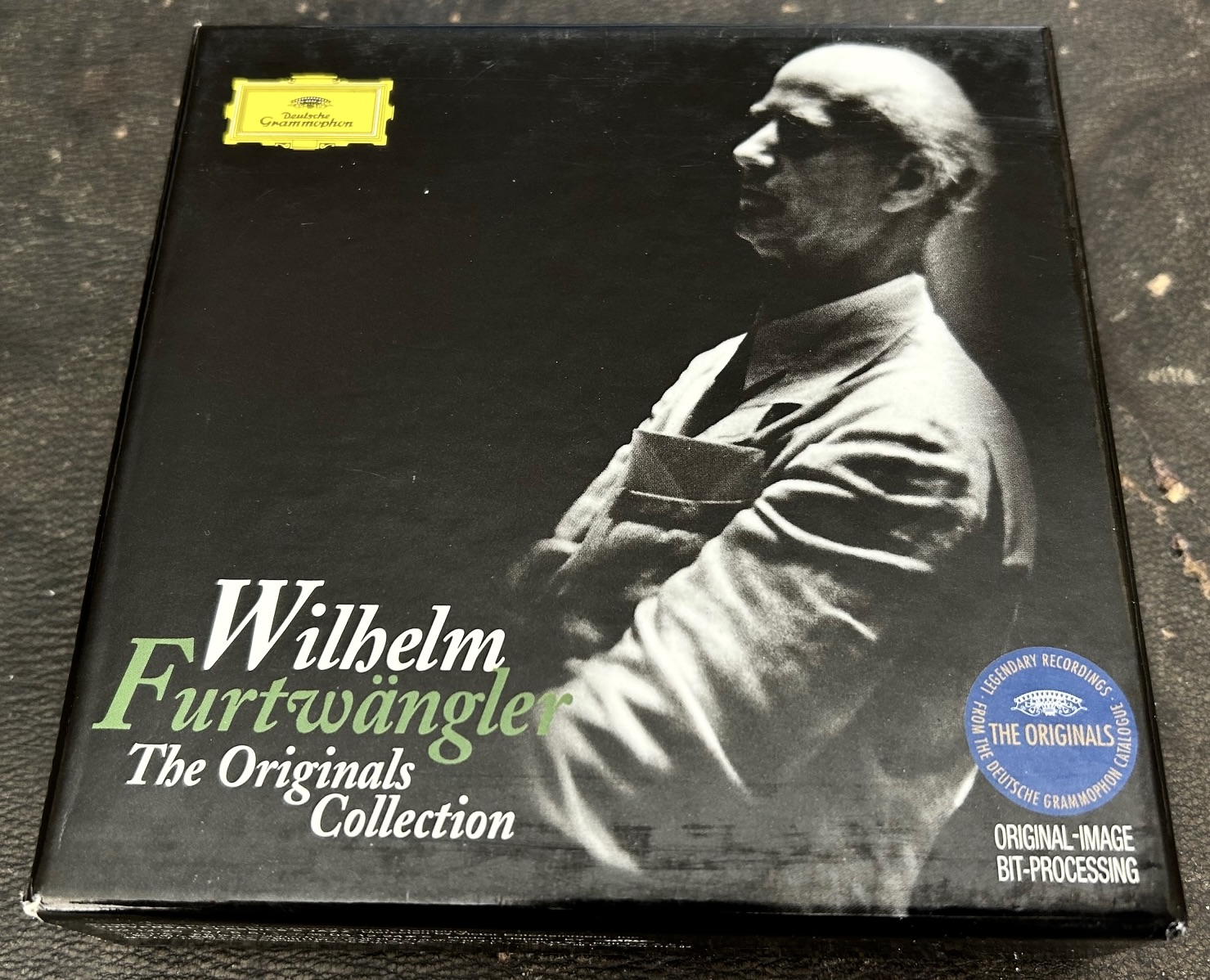

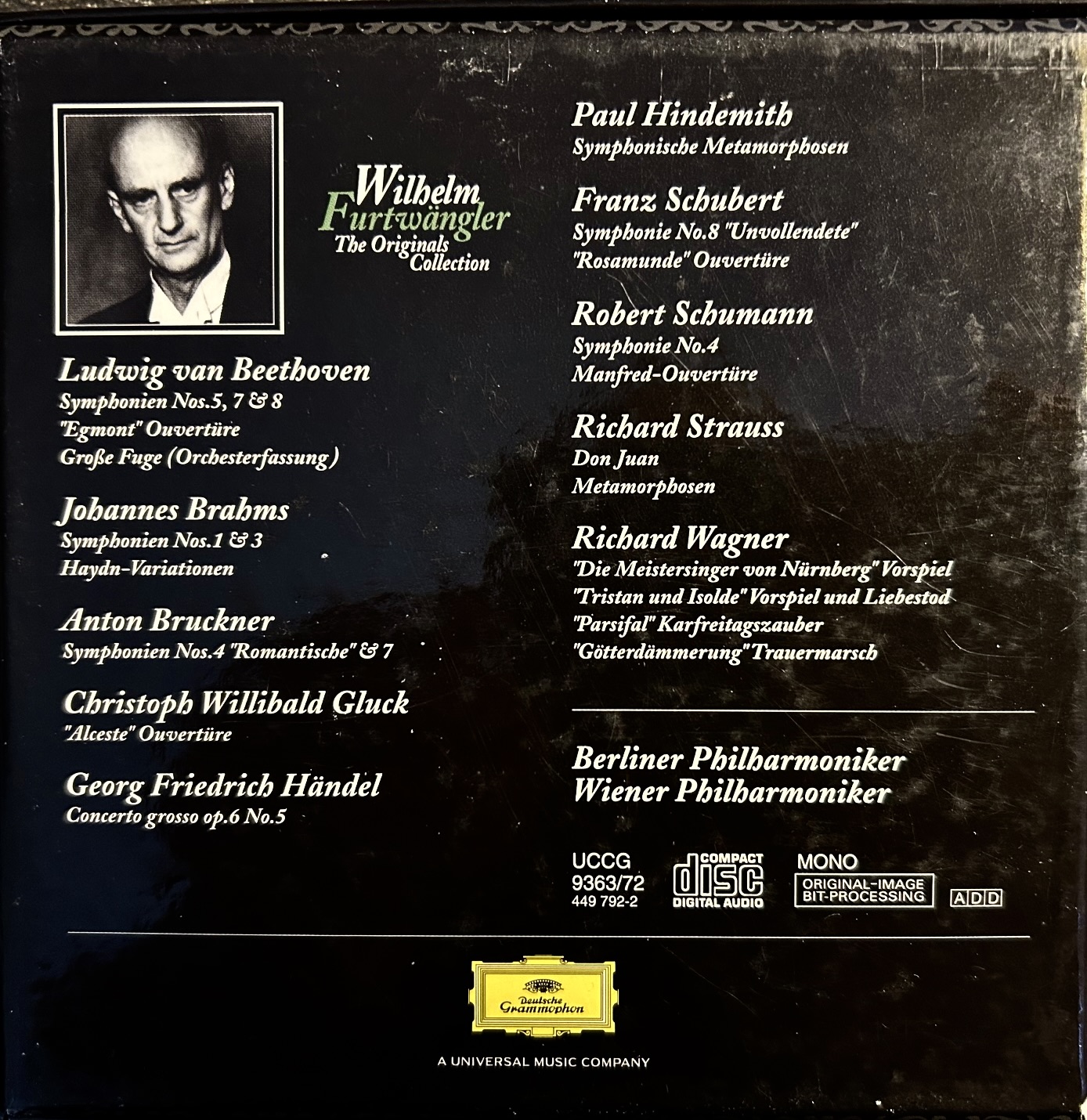

I decided to further my knowledge by going in on a nice OOP Japanese CD-set of his Deutsche Grammophon recordings, including his exceptionally fine Schumann 4th, drawn from a massive "complete" Japanese set.

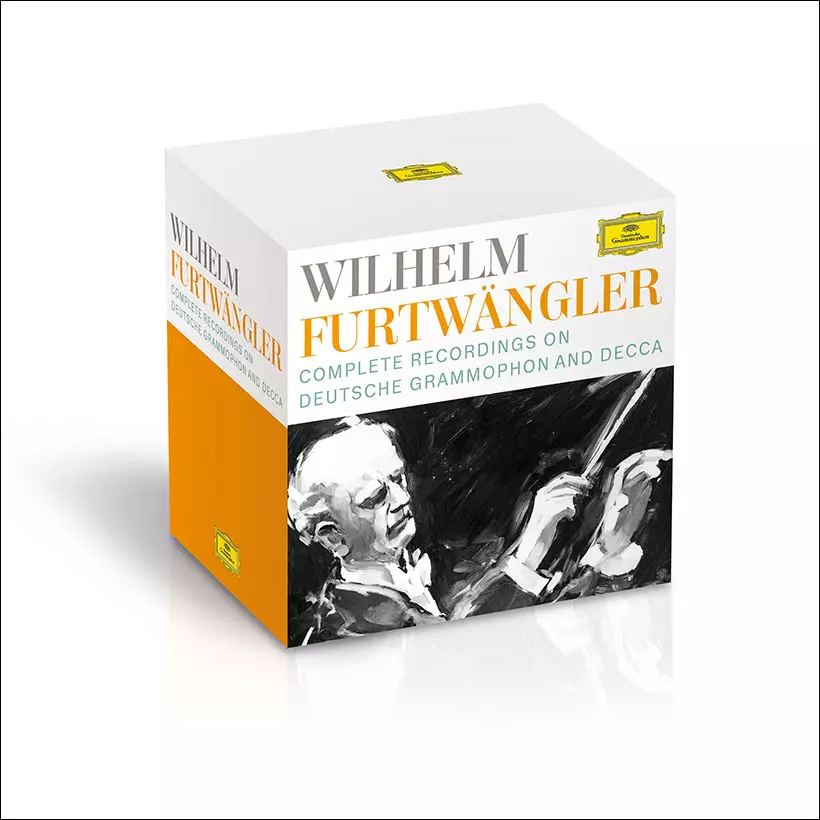

This set has since been supplanted by the Complete DG box set.

There is now also a very fine 4LP vinyl set of several key works recorded in stereo, including superb recordings of Haydn's 88th, Schumann's 4th, and Schubert's Great C major symphonies plus Furtwängler’s own 2nd Symphony. The records were mastered and cut at Emil Berliner Studios and sound magnificent. It's still available, and highly recommended.

I will also mention here the Warner/EMI "Complete" Recordings set that has since come out on CD, which is supposed to have excellent remastered sound. (N.B. - the term "Complete" in relation to these CD sets should be taken with a pinch of salt).

Anyway, back in 2020 I supplemented those Originals Collection CDs with the excellent Audite CD-box of his post-WWII RIAS broadcasts with the Berlin Philharmonic, which is really the essential one-stop shopping destination for Furtwängler “live” in somewhat decent sound. (It was also issued as a 14-LP set of selected works from the larger CD set - and you can probably still find this).

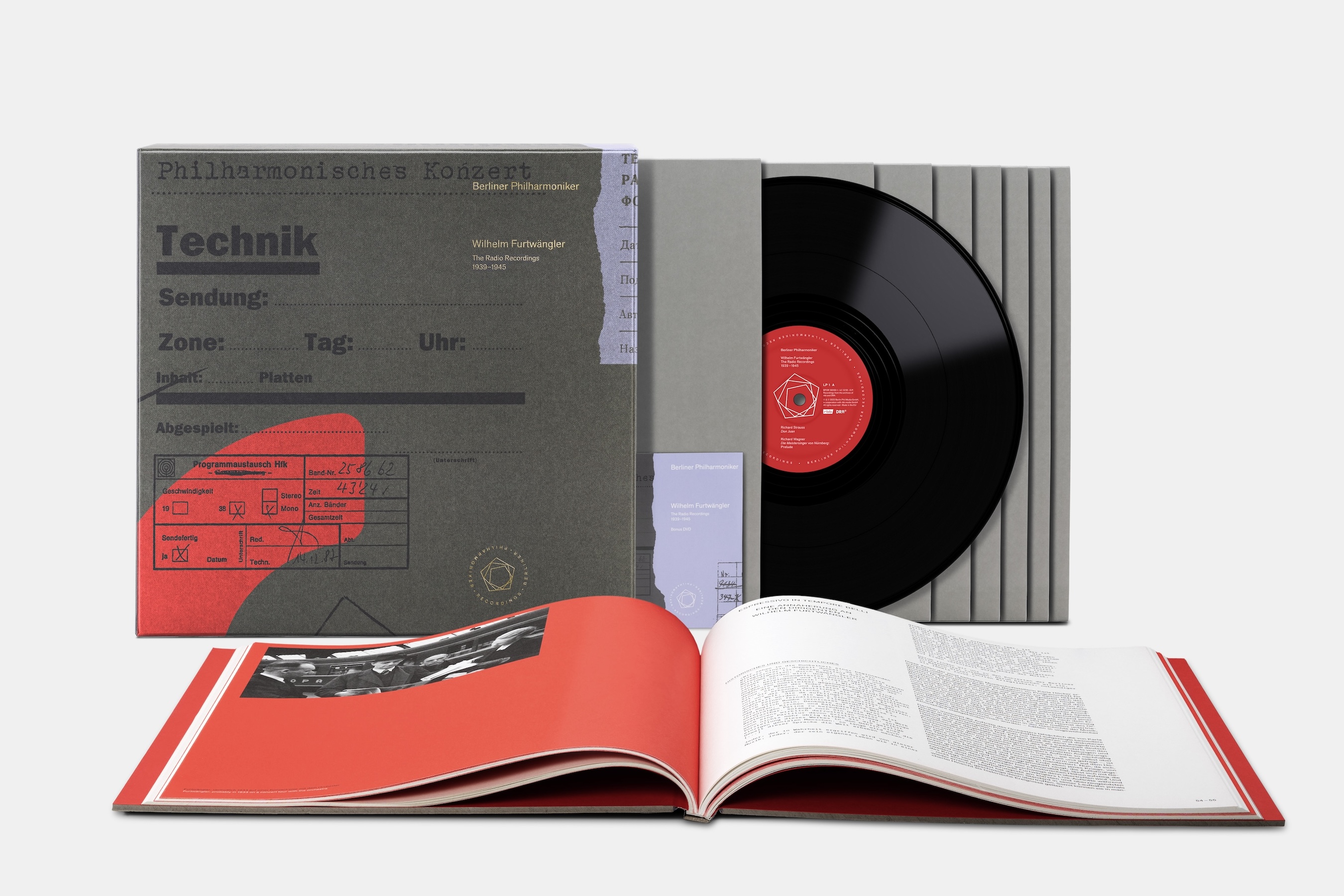

But then I discovered that just a few months earlier the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra’s in-house label had issued a sweeping 22-CD/SACD set of all the surviving Radio Recordings Furtwängler had made with the Berlin Philharmonic in Berlin during World War II, a testament not only to a particular musical legacy, but a unique moment in history. I bought it immediately. Making my way slowly through this extraordinary set of recordings, reading about the history behind them, proved to be one of the great musical voyages of discovery for this classical music lover and relative Furtwängler newbie. (Thank you, pandemic!)

That set, packaged in the BPO label house style with state-of-the-art design and accompanying documentary materials and essays, is the basis for this 2022 vinyl edition being reviewed here, which extracts a number of the outstanding recordings and presents them on eight beautifully pressed 180gram vinyl platters. The records were mastered and cut by the same folks over at Emil Berliner Studios responsible for the state-of-the-art Original Source Series, Rainer Maillard and Sidney C. Meyer. Yet again I find myself marveling at this team’s engineering and vinyl cutting acumen (at this point I am an unapologetic Sidney groupie, having picked up a few of her incredible sounding non-classical platters too - go check out the iconoclasm of her Discogs catalogue).

Even if you already have the CD/SACD set, if you are into vinyl I think you should seriously consider this set. I found the LPs ever so slightly more pleasing to listen to than the already authoritative CD/SACDs (maybe more a reflection of my turntable chain than any intrinsic superiority). Both the vinyl and CD/SACD transfers exhibit a mild “phantom” stereo soundstage created via discrete phasing processing; while some may object to this non-purist approach it never bothered me, and is a far cry from the ghastly “Electronically Reprocessed for Stereo” LPs of yesteryear. (Therefore you will not need a dedicated Mono cartridge to get the best out of this set - it is cut with a stereo head).

Another bonus of the vinyl set is you get all the same packaging in a larger, even more deluxe format. As with all the Berlin Philharmonic label releases - especially the limited edition vinyl sets - these are genuine collector’s items which will elevate any collection that contains them, and will give you hours of listening pleasure. This set is especially distinguished by the high quality of the essays in the accompanying book, which will tell you all you need to know about Furtwängler and the circumstances around these recordings - and it’s really fascinating stuff. Let me single out the profoundly illuminating essay by Richard Taruskin.

The Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra, generally considered one of the world’s platinum ensembles, was one of the first performing arts organizations to establish its own in-house record label in response to the increasing vagaries of the classical recording industry.

Along with its streaming platform, the Digital Concert Hall, the BPO has set the highest bar for such enterprises. The label has released one drool-inducing set after another, always with eye-catching design, unique and sturdy packaging, and exemplary documentation. Most sets come out as CD/Blu-Ray packages first, followed by cheaper CD/SACD iterations. (I simply do not understand this; these should all be dual-layer CD/SACD sets from the get-go, as was the Furtwängler box). In some cases, limited edition vinyl sets have followed. Then there have also been the “Special Event” Direct-to-Disc releases of Simon Rattle’s Brahms Symphony cycle, and Bernard Haitink’s Bruckner 7th, a spellbinding record of his final concert with the orchestra. Both sets now command exorbitant prices on the used market.

Before I get into the records themselves in this Furtwängler box and their sound, there is a lot of fascinating history tied up in this set, not least the historic place the original Wartime radio tapes hold in the history of recording technology. This is all covered in fascinating detail in the set’s accompanying essays and photos, but I will delve into some of it here.

THE TECHNOLOGY AND HISTORY OF THE WARTIME FURTWÄNGLER/BPO RECORDINGS

That these recordings exist at all is something of a miracle: technological - because they were the first recordings made on tape; historical - because they survived the fall of Berlin, being taken to the Soviet Union, and eventually returned to the German archives some 40 years later.

Beginning in 1932 the electrical company AEG and the chemical company I.G. Farben had endeavored to create their new “Magnetophon” recording system, which would allow for the capturing of sound on tape with a hitherto unheard of degree of sonic fidelity. Once that could be achieved, the restrictions of only being able to record in 4 minute segments (owing to the nature of existing recording systems) would be a thing of the past.

The AEG Magnetophon

The AEG Magnetophon

But there was a persistent problem with the prevalence of background noise which meant that the recording of prestigious spoken word and musical programs for broadcast was not possible.

Dr. Walter Weber

Dr. Walter Weber

It was an engineer at the Reich Broadcasting Corporation, Dr. Walter Weber, who finally figured out a solution to this problem, and the floodgates opened. The Magnetophon would now allow whole classical works (and movements of works) to be recorded without interruption - with the ability to use tape editing to correct mistakes.

The "Old Philharmonie" Hall in 1935. It was destroyed by bombing in late 1944. (Photo: Rudolf Kessler)

The "Old Philharmonie" Hall in 1935. It was destroyed by bombing in late 1944. (Photo: Rudolf Kessler)

It was Furtwängler and the Berlin Philharmonic who were the first to use this new reel-to-reel machine to tape a concert on December 16th, 1940. This was the dawn of the modern recording era. There is a huge jump in recording quality, as anyone listening to these records who has also heard Furtwängler’s pre-War recordings will attest to.

Furtwängler himself, who had been reluctant to record his performances in large part because of the sonic shortcomings of contemporary systems, and the need to record in 4-minute chunks (anathema to his entire working method and aesthetic) if in the studio, immediately recognized the possibilities. Friedrich Engel, in his detailed account of this fascinating technological history - part of this set’s book - quotes the Director of the AEG Laboratories, Hans Schiesser, as saying: “Furtwängler was delighted by the quality of the recording. He had it played over and over. Never before had he been able to listen to a recording while or shortly after it was made - and of such quality into the bargain.” (Apparently there were a number of stereo recordings made as well over the next few years, but these tapes are lost).

Several senior members of the Nazi hierarchy owned their own personal Magnetophon playback-only machines, including Hitler himself. Goebbels in his diary noted that in 1942 the Führer had received a machine as a birthday present, and was known to have also received tapes of Furtwängler's recordings. As Friedrich Engel notes in his essay: "... Imagine Bruckner in the 'Wolf's Lair'..."!

All the Berlin Philharmonic wartime concerts thereafter were committed to tape and stored in the archive of the Reich. Once the Soviets occupied Berlin in 1945, some 1500 tapes from the classical archives in Broadcasting House were sent to Moscow, where they largely remained until the early 1990s. The thawing in political relations between the two countries resulted in a treasure trove of these tapes being returned to Germany. Naturally there are missing tapes, with some existing only as copies of the originals, but the fact remains that the source material for the majority of the recordings contained in this box set is of a significantly higher quality than one would normally expect for this period of recording history. The Germans, with their Magnetophon, led the way in the new technology, and had planted the seeds for the modern record industry.

It is something of a miracle that these early reel-to-reel tapes not only survived the destruction visited upon Berlin at the end of the War, but also the vicissitudes of the post-War era in the Soviet Union, to eventually find their way home, and, finally, on to the CD/SACD and LP sets we can all now buy.

One of the surviving wartime reel-to-reel tapes (Photo: Sebastian Reimold)

One of the surviving wartime reel-to-reel tapes (Photo: Sebastian Reimold)

Continued in Part 2...

.png)