Karajan, Bruckner, and The Next Generation of Deutsche Grammophon’s Original Source Series - Part 1: “Past is Prologue” - A Conductor’s Journey

A Deep Dive into the History and Technology behind this Epic AAA Reissue, mastered and cut directly from the 8-track master tapes

Between 1975 and 1982, the renowned Austrian conductor Herbert von Karajan and the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra recorded and released the nine numbered symphonies of the great Romantic composer Anton Bruckner for Deutsche Grammophon. For Karajan it was the culmination of a lifetime studying and performing these works. The cycle, coming at the beginning of the Bruckner revival, was one of the earliest complete recordings, and has remained a benchmark ever since. However, for a variety of reasons (including the conductor’s embrace of early digital technology for his recordings of the three early symphonies), for all its formidable musical virtues the cycle suffered from variable sonics in all its incarnations on LP, CD and other formats.

For this reissue as part of the Original Source series, celebrating the bicentenary of the composer’s birth, the engineers at Emil Berliner Studios have pushed the technology of vinyl mixing, mastering and cutting into new territory, and in the process have restored this lynchpin not only of the Bruckner discography, but of Karajan’s and Deutsche Grammophon’s catalogues, to a place of sonic and musical excellence that few, if any, can match.

It seemed only right for a release of such significance to offer as comprehensive a view (musical, technological, and aesthetic) as possible of this seminal set here at Tracking Angle. In Part 1 I discuss Karajan’s long history with Bruckner, and why his partnership with the Berlin Philharmonic was particularly suited to this music. In Part 2 you will be hearing from Rainer Maillard at Emil Berliner Studios about the history and development of DG’s recording technology, and how it was applied to this cycle (with an extensive discussion of the role of the Berlin Philharmonie’s acoustics in these recordings). This is followed by a discussion of how he and master cutting engineer Sidney C. Meyer tackled the challenge of working directly from the 8-track master tapes for this release (a first in the world of vinyl production). In Part 3, we continue with an examination of how Maillard was able to “revive” the early digital recordings of Symphonies 1 - 3, and conclude with an overview of the entire set.

Tracking Angle and DG will also be posting a discussion that took place recently between Johannes Gleim at DG (the Original Source Project Director), Maillard and Meyer, myself and last - but by no means least - Tracking Angle’s Editor-in-Chief, Michael Fremer. This video includes a truly fascinating behind-the-scenes video look at the project made by Emil Berliner Studios. Anyone remotely interested in the recording arts and sciences - even if they are not especially into classical - will want to watch this.

So - take a deep breath - and let’s dive in…

"PAST IS PROLOGUE" - A CONDUCTOR'S JOURNEY

There’s an old joke that did the rounds for years. Herbert von Karajan, the renowned Austrian conductor, gets into a cab in Vienna. “Where to, sir?” asks the cabbie. “It doesn’t matter,” replies the maestro, “I’m wanted everywhere”.

Fanciful and apocryphal though it may be, there is nonetheless more than a germ of truth in this joke. Karajan was, for many decades, THE most commercially successful classical musician and recording artist in the world, holding simultaneous posts at the world’s most prestigious classical music organizations. In the 1950s, while conducting the Philharmonia Orchestra in London, he was also Music Director at the Vienna State Opera. In the 1960s he was well into his lifetime tenure as Principal Conductor for Life of the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra while also being Artistic Director of the Salzburg Summer Music Festival, and later also the Salzburg Easter Festival which he began in 1967. Add to that his numerous tours and performances all over the world.

In his lifetime Karajan attracted equal amounts of admiration and vitriol, passionate praise and snarling criticism. His so-called “Nazi past” - thoroughly examined by numerous scholars, foremost of which was Gisela Tamsen (referenced in detail in Richard Osborne’s authoritative biography, Karajan - A Life in Music) - remained a cudgel with which to beat down his artistic accomplishments. His good looks (amply exploited on album covers and in publicity material), and his love of fast cars, fast planes, climbing, skiing and the trappings of the celebrity jet-set life only fed the ire and umbrage of the Karajan naysayers. “How could such a superficial man possibly be a great artist?” they opined.

Karajan at the Controls of his Airplane

Karajan at the Controls of his Airplane

Quite easily, it would seem. Take a look at the man’s biography, and you will see his prodigious talents, exhibited from an early age, are matched only by his formidable self-discipline and, yes, overarching ambition. Does that automatically make him a great artist? No. But it goes a helluva long way. The rest is in the ears of the beholder.

Karajan definitely has his blind spots, and for sure his style of music making may not be your cup of tea. But I defy any of you not to respond to any one of a whole clutch of recordings I could play you (including this Bruckner cycle) with at least some sense of astonishment.

The bad vibes and jibes from many in the critical establishment have continued long after Karajan’s death in 1989. He simply remains a polarizing figure, in a way that often has little to do with his actual accomplishments and legacy. That legacy is, fortunately, able to be reassessed via his voluminous recorded catalogue, of which the Bruckner cycle under consideration here remains one of the central foundations.

I can think of no better self-contained cycle of Karajan recordings by which to examine what made Karajan Karajan, and in this stunning sonic refurbishment we are afforded the clearest possible view into the aesthetic and musical priorities of one of the 20th century’s most important conductors, musicians - and perhaps most significantly for readers of Tracking Angle - recording artists.

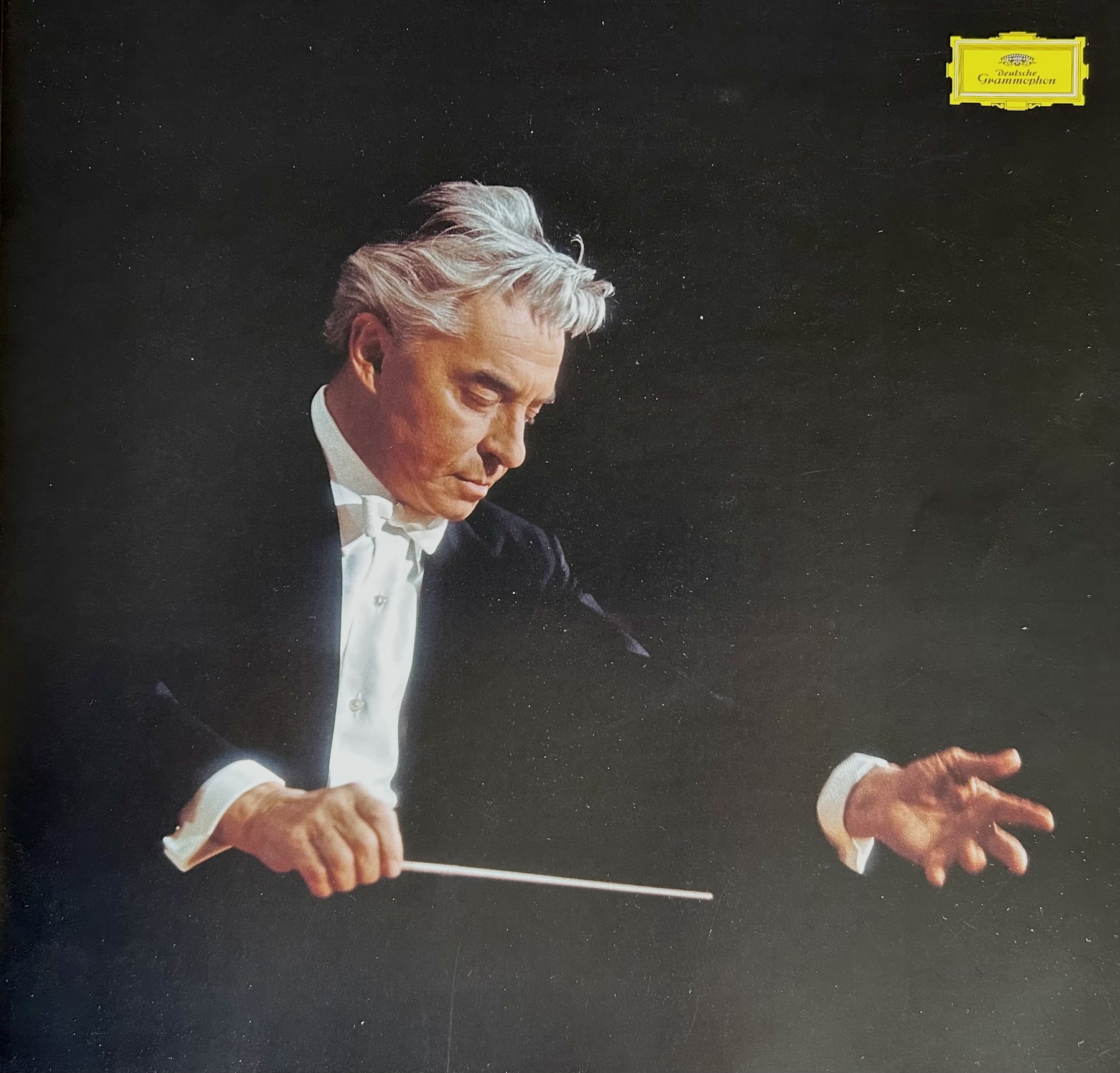

Herbert von Karajan from the Cover of the Bruckner Symphony Edition Booklet (Photo: DG/Siegfried Lauterwasser)

Herbert von Karajan from the Cover of the Bruckner Symphony Edition Booklet (Photo: DG/Siegfried Lauterwasser)

But don’t just take me word for it. Karajan’s affinity for Bruckner’s idiom has inspired many of today’s top Bruckner conductors. Here’s the great Italian maestro, Riccardo Muti:

“The first memorable Bruckner performance I heard was in London while I was Chief Conductor of the Philharmonia back in the 1970s. The Berlin Philharmonic was on tour with Karajan performing Bruckner’s 8th Symphony at the Royal Festival Hall. It was an incredible performance; I remember afterwards being almost at the point of throwing away my baton! Karajan’s depth of understanding of Bruckner was unique. I would call it a natural interpretation, with that most difficult thing in art - a quality of simplicity. It was after hearing this Bruckner 8th with Karajan that I decided to conduct my first Bruckner symphony, the composer’s own First, in Florence.”

Or Christian Thielemann:

“My first encounter with Bruckner was as a a child listening to Karajan’s concerts in Berlin. I well remember him conducting the 5th Symphony. I was blown away by the end and immediately felt it to be a beautiful piece. Some years ago the musicians of the Vienna Philharmonic recounted how Karajan would tell them not to play the 5th like a school exercise - ‘I know what this theme is, and the next, and where it reappears, and so on’. On the contrary, everything should be amalgamated, of a piece.” [Spoiler alert: the recording of the 5th in this box is stupendous - MW].

This set is also a fitting testament to the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra of the Karajan era in its prime, an instrument of uncanny beauty, power and infinite dexterity (albeit within Karajan's stricture that it should never make a sound that was not beautiful). The orchestra had its own long history of Bruckner performance dating back to the years when Arthur Nikisch was its Principal Conductor, an inveterate fan of the composer since he had actually played in a performance of the 3rd Symphony when he was a young violinist in the Vienna Court Orchestra.

This new set of Original Source records wipes away years of technological shortcomings, compromises, and missteps of previous incarnations on LP and CD, revealing with something akin to a sonic laser beam what’s on the master tapes with a fidelity that will take your breath away - over and over again...

Thomas Brandis, Concertmaster of the BPO under Karajan

Thomas Brandis, Concertmaster of the BPO under Karajan

Another joke, told this time by Thomas Brandis, who became Concertmaster of the Berlin Phil from 1961 when he was 26, remaining until 1983:

"You've probably heard the famous Karajan joke. Bernstein, Böhm and Karajan are sitting together arguing who's the greatest conductor on earth. Bernstein says that God appeared to him and said, "It's you!" Böhm replies that that's not very likely because God appeared to him and told him, "It's you!" At which points Herbert von Karajan drily adds, "I said nothing of the sort!”

The popular belief that conductors think of themselves as “God” (or at least someone God would talk to) is entirely understandable, given the whole conductor-ly process of standing in front of a huge orchestra (plus soloists, vocalists and choirs as need be) and bending said performers to your will. This notion is hardly contradicted by the whole pseudo-religious, indeed worshipful, process of entering a vast concert-hall (the Church or Cathedral), taking your seat amongst other believers (the Congregation) and listening with rapt attention, and occasional fervor, to the musical pronouncements from the performers onstage guided by the Minister on the podium.

The “conductor as God” concept is not one most modern-day practitioners of this elusive craft would be comfortable with, but for Karajan’s generation and earlier it was, at the very least, a kind of wink-and-a-nod understanding. With the explosion of the commercial classical record industry in the 1960s and 70s, with all its attendant image and brand building, conductors were elevated to god-like status to sell records. Rivalries between competing conductors and labels (often purely the invention of marketing departments), like Karajan on Deutsche Grammophon vs. Solti on Decca, only enhanced this sense of Musical Titans thrashing it out in the Heavens for the edification of us mere mortals below.

But, above all else, conductors are necessarily supreme technicians (or at least they used to be), who must wield superior musical technique, knowledge and vision in order to be able to mold a large group of individual virtuoso instrumentalists into a cohesive performing unit. So also take note of what Brandis has to say about working with Karajan, from an interview in The Strad from 2015.

“I learnt so much from him. He was fantastic on dynamics and that’s what I try to teach my students. I also discovered how to use my bow and how not to make accents, both in chamber music and in Beethoven symphonies.

“First I had to get used to his beat. The orchestra was always later than him, a tradition that came from Furtwängler. I had to learn to play a little late, or I would have been playing solo. Karajan hated it – he always shouted at the orchestra. In rehearsal they played in time, but in concerts they were always late. But it gives a sense of excitement.

“We didn’t like all of his ideas – he didn’t like any attack on down bows or up bows which was good for Bruckner, Brahms and Wagner, but not Mozart or Bach. I missed the articulation and when I listen to those recordings today I don’t like it. He had a wonderful way of rehearsing, though. He knew what he wanted and was clear. His rehearsals were intense and the orchestra was disciplined, which they weren’t always with other conductors.

“Arguing with him wasn’t a possibility. He was God. He was always right even when he was not right. In Japan we played Tchaikovsky’s Fifth Symphony, and he conducted one beat too many. We played in time but the brass didn’t so it was terrible. The next day we rehearsed that place for half an hour. He was so angry and didn’t recognize that he had made a mistake.”

Upon Brandis’s death in 2017, Berlin Phil. orchestral board member Knut Weber wrote the following:

“Thomas Brandis’s playing gives a condensed account of the qualities of the Karajan era: a rich, singing tone and an unerring sense of musical dramaturgy.”

Absolutely the qualities you will hear in every moment of this Bruckner cycle.

KARAJAN and BRUCKNER

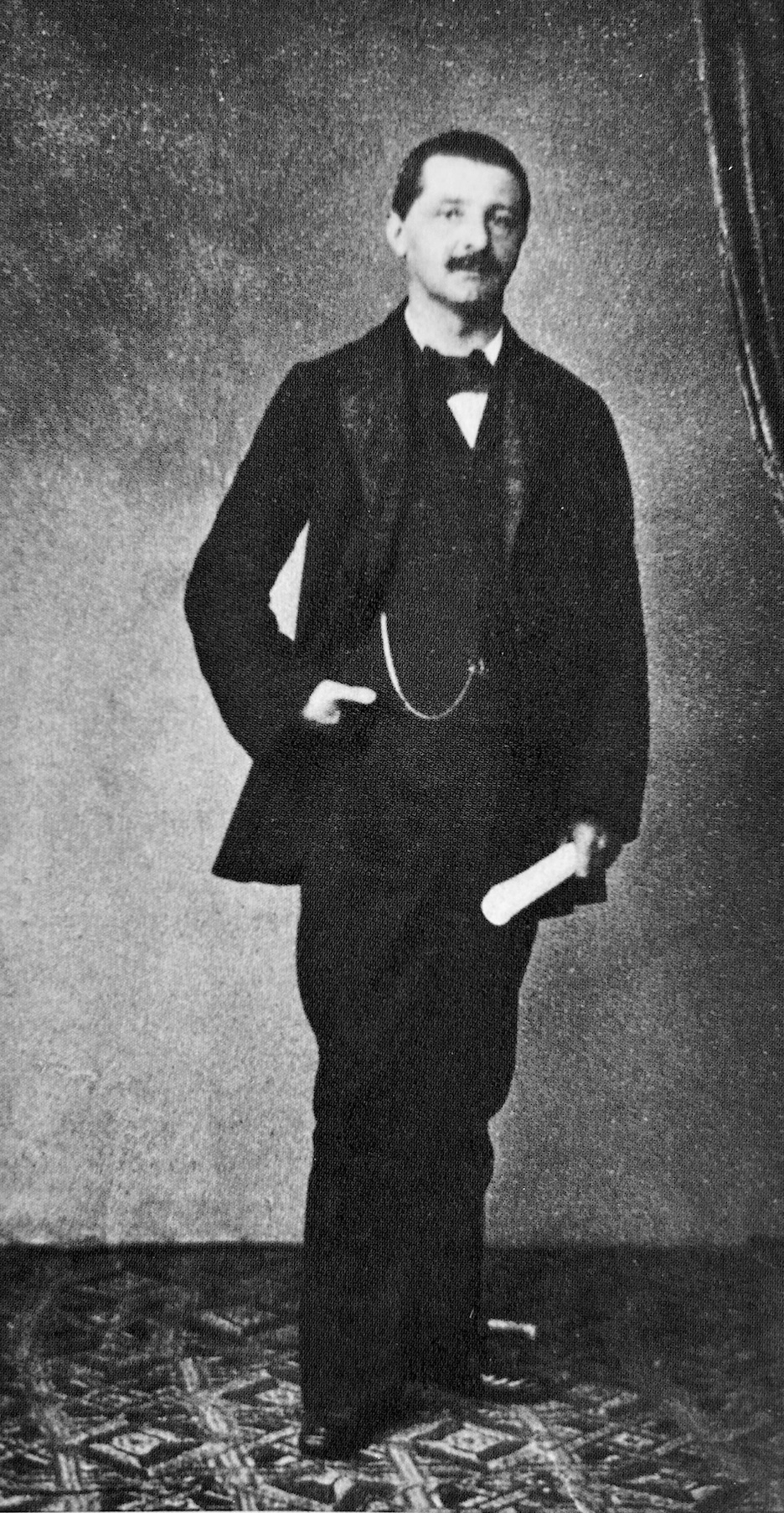

Anton Bruckner in 1854

Anton Bruckner in 1854

Karajan’s connection to Bruckner runs deep and long.

Karajan was born in Salzburg, a picturesque Alpine town long since overrun with Sound of Music tourists and endless shops selling every conceivable item branded with Mozart’s likeness.

But strip away all these accoutrements of the tourist industry, think back to what it must have been like during Karajan’s childhood during the first decades of the 20th century, and you’re not far away from the world into which Bruckner himself was born, the rustic village of Ansfelden near Linz. The composer’s ancestors, going back to the 15th century, lived in an area of Austria within a mere 25-mile radius.

Linz in 1863, close to Ansfelden, where Bruckner was born

Linz in 1863, close to Ansfelden, where Bruckner was born

Bruckner’s music is infused with the spirit of the rural and mountain landscapes of his native Austria. It is impossible to listen to it and not conjure up visions of pastoral lowlands, brooks and rivers, Alpine pastures and, towering above, the vast crags and spires of the high mountains clawing at the heavens. Bruckner’s Catholic faith also lies at the heart of his music, even in his secular symphonies which - at their heart - remain fervently spiritual utterances. Therefore it is hardly surprising that his music also evokes the arches, columns and spires of the Cathedral. As such, Bruckner embodied one of the defining aspirations and characteristics of the Romantic period: to achieve an expression of the divine in Man through his relationship with the world around him, and especially the beauties of Nature.

Bruckner's Birthplace, now a Museum (r.) with the Church of Ansfelden

Bruckner's Birthplace, now a Museum (r.) with the Church of Ansfelden

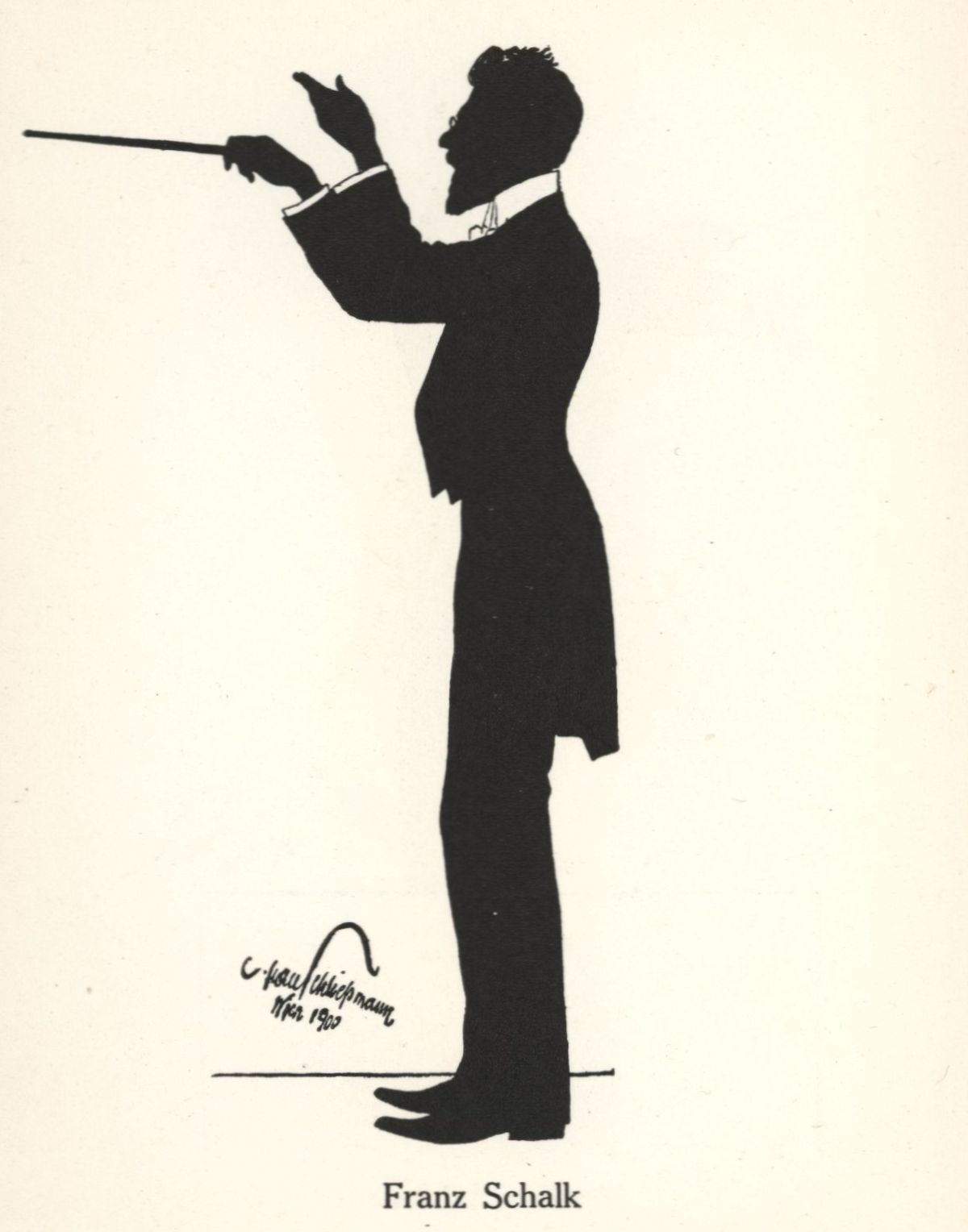

Karajan, with his love of the mountains and his reveling in his physical self both through his conducting and his passion for sport, is a perfect match for this Romantic impulse in Bruckner’s music. He actually came into contact with one of Bruckner’s most prominent pupils, Franz Schalk, during his student days in Vienna - sitting in on rehearsals, but never formally studying with him. Considered something of a journeyman conductor, Schalk was co-director of the Vienna State Opera with Richard Strauss (who later resigned because of tension between the two men). Schalk was also a somewhat controversial editor of Bruckner’s symphonies, giving the first performance of the 5th Symphony (in his own truncated version) in 1894 after the composer’s death (Bruckner never heard a note of this work performed during his lifetime).

Franz Schalk by Hans Schliessmann (1900)

Franz Schalk by Hans Schliessmann (1900)

The student Karajan observed Schalk keenly though quietly, cat-like from a distance - as he did many conductors during his formative years. Watching Schalk at work, Karajan absorbed much of what it took to be a successful Kapellmeister within the politically volatile atmosphere of one of the world’s foremost opera houses.

Interestingly, it was with a Bruckner symphony - No. 4 - that Karajan made a strong impression early in his career, during his time as Music Director in Aachen, beginning in 1935, a period he referred to in 1951 as “the happiest years of my life.”

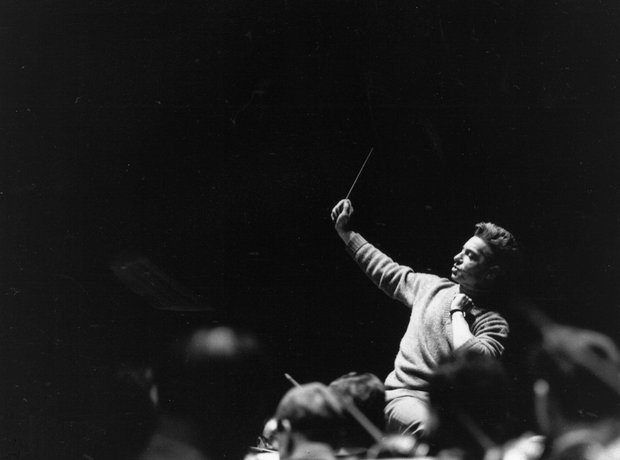

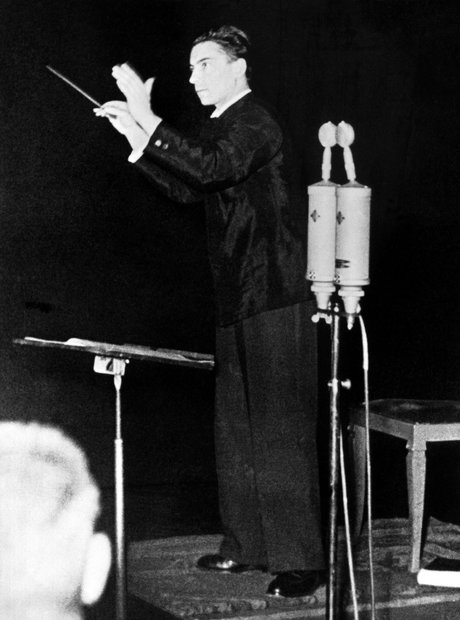

Karajan in 1938

Karajan in 1938

Richard Osborne, in his superb biography (which I have drawn on extensively for this article, and which I heartily recommend as one of the best books ever written about a musician, a conductor, and the classical music industry in general), brings us this account of the occasion:

“A performance of Bruckner’s 4th Symphony, in Robert Haas’s new performing edition, also took the critics by the ears…. Karajan instantly made an impact with his scrupulously clear unfolding of the newly revised text. Local critic Franz Achilles wrote of Karajan’s inborn feeling for the natural splendors and cathedral-like spaces of the music, something he attributed in part at least to his Austrian roots and his familiarity with the cathedral architecture of Salzburg and St. Florian [where Bruckner had served as organist for many years - MW]. Had he known it, he might have added Karajan’s knowledge and love of the organ as another factor in his precociously complete understanding of the Bruckner idiom.”

During the War years, Karajan was based in Berlin but denied the opportunity to conduct the Berlin Philharmonic by its Principal Conductor, Wilhelm Furtwängler, who was consistently rankled by the younger man’s success, and would refer to him merely as “K”. Karajan had joined the Nazi Party in the 1930s in order to be able to work at all, but he also imperiled his prospects by marrying a woman who was partly Jewish in 1942. His relationship with the authorities remained testy but he was able to find work beyond Berlin.

During this time, Karajan turned increasingly to the music of Bruckner for solace. Something in Bruckner’s music spoke to the peril of the times, yet also offered a way through adversity, a path towards some level of spiritual equanimity, if not complete redemption. Listen to any of the recordings in this set and you can hear how deeply Karajan identifies with this music, and you can detect traces of the emotional trauma and anxiety of those War years (for example the pulverizing brass detonations in the 5th Symphony in particular, redolent of battlefield artillery and bombs raining down from on high).

One of the main ways in which Karajan preserved his sanity during this period was through spending time at his lakeside retreat at Thumersbach. The winters of 1942-3, and 1943-4 were spent with plenty of time on the ski slopes. These mountain vigils greatly influenced his thinking and music-making.

Thumersbach (with the Pension Lohninghof in foreground) in the 1920s

Thumersbach (with the Pension Lohninghof in foreground) in the 1920s

In a letter to his mother from July 1944, written while Karajan was taking a cure for back and liver problems, the conductor elaborated:

“What must be done here is to free ourselves from all those earthly things that weigh us down, and to return music to those spiritual heights from which they were born - this is what I am convinced of, and I wanted to share this with you. With this insight that has so powerfully impressed me, I now for the first time understand this music correctly.”

The music to which Karajan was referring was Bruckner’s 8th Symphony, which he had started recording with the Berlin Staatskapelle for Berlin Radio the previous month. It’s a fascinating endeavour, begun in mono, completed in stereo - an early example of Karajan’s eager embrace of new technology.

Karajan recording in the 1930s

Karajan recording in the 1930s

Let Richard Osborne take up the thread:

“(Karajan) was not the only musician who found Bruckner’s music speaking to him in a special way. At a time when the works of Beethoven must have seemed almost crassly optimistic and those of Brahms too bourgeois and emotionally hesitant it was left to Bruckner to articulate a sense of something at once grand and terrible, epic and Angst-ridden: the forces of darkness and death trampling, if not entirely obliterating, the old certainties of priest and peasant.”

[Though listen to Furtwangler’s final live performance with the BPO of the last movement of Brahms’ First Symphony in 1944 before Berlin fell to the Allies, included on the BPO label’s box set of the conductor’s wartime radio recordings, with the sound of artillery clearly audible pounding in the distance, and you will hear all this plus a searing elegy for the fall of Germany - MW].

Osborne continues:

“What is astonishing about the Karajan Bruckner Eighth - in comparison with Bruckner recordings from this same year by conductors such as Furtwängler and Knappertsbusch - is the sense it conveys of a mood that is both awesome and imperturbably calm…”

Go listen to the recording of the Eighth included in the current set and you will hear much of the same - even though it was not recorded during wartime.

From this time onwards, Karajan was to feature Bruckner in many of his concert programs, and these performances would latterly attract sell-out crowds (as Riccardo Muti mentions above).

However, he wasn’t to take Bruckner into the recording studio again until 1957, with the BPO: again the 8th Symphony, recorded for EMI/Columbia.

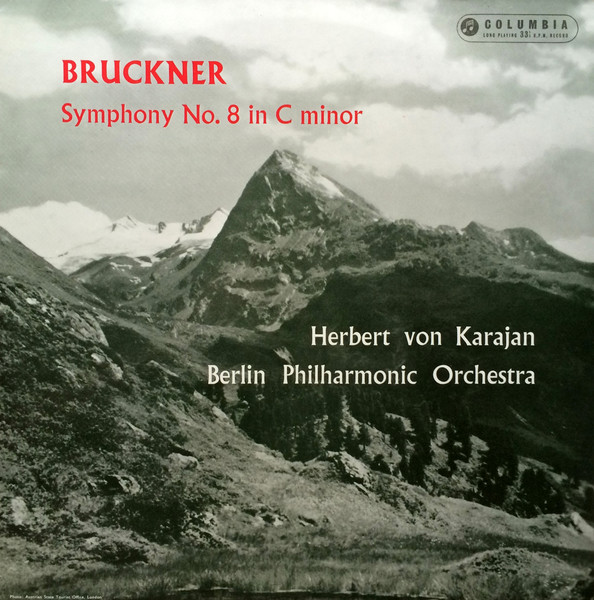

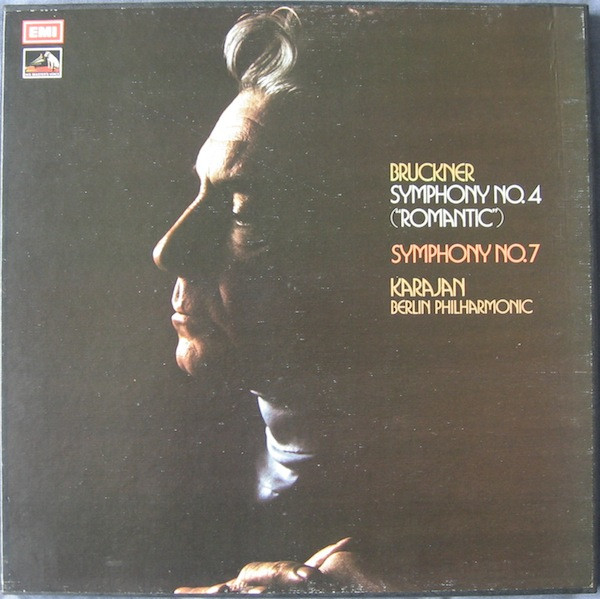

Original UK Mono of Karajan's 1958 Release

Original UK Mono of Karajan's 1958 Release

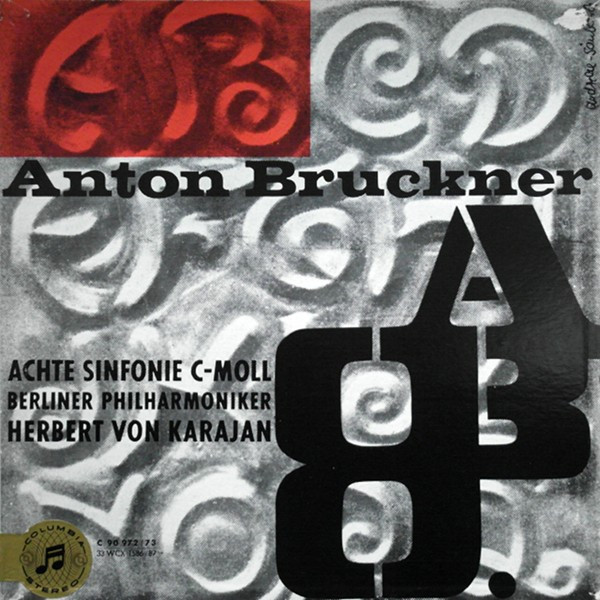

Original German Stereo Release

Original German Stereo Release

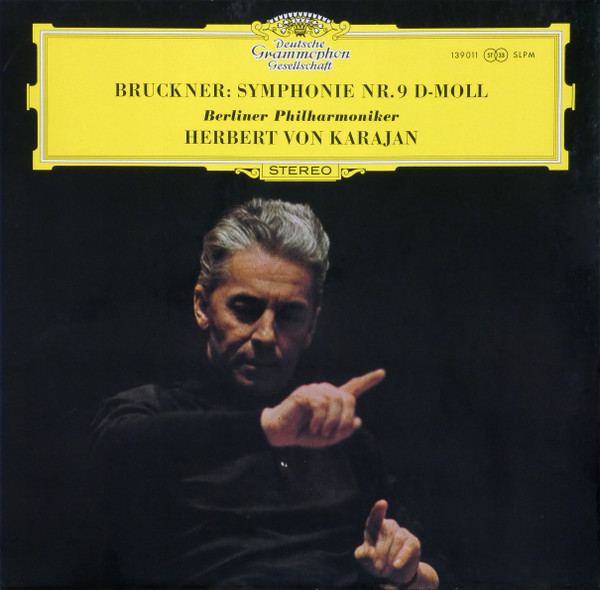

Then, in 1966, he laid down a much admired version of the 9th for DG.

This was followed up in 1971 by equally fine versions of Symphonies 4 and 7 for EMI, all recorded in the Jesus Christus Kirche in Berlin.

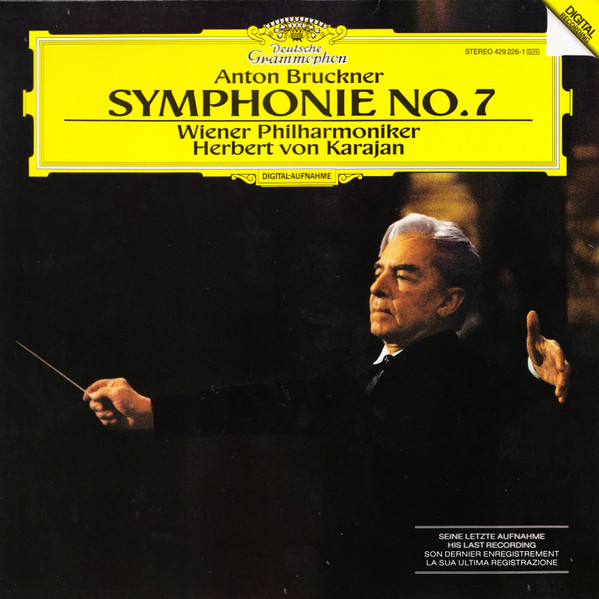

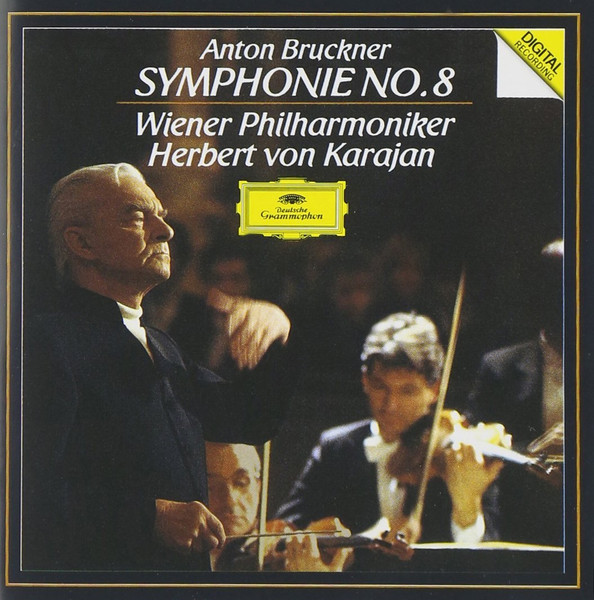

In 1973, Karajan launched the Salzburg Whitsun Festival, and devoted it almost exclusively to the music of Bruckner - an apt choice for this religious season. The 4th, 5th and 8th Symphonies rubbed shoulders with Mozart’s Requiem. Did he know he was drawing close to setting down his thoughts on the entire Bruckner symphonic canon? Possibly. It should be noted that beyond this benchmark cycle for DG under consideration here, recorded between 1975 and 1982, Bruckner’s symphonies remained defining works of Karajan’s emotional, spiritual, and musical core. Two of his final recordings before his death in 1989, of searing live performances with the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra, are of the 7th and 8th Symphonies, and are essential items for any Karajan collector - or indeed any Bruckner enthusiast.

THE "KARAJAN SOUND" AND BRUCKNER

The catalogue is full to bursting with great (and many, many not-so-great) Bruckner recordings.

So why is this Karajan/Berlin Philharmonic cycle so central to any consideration of this repertoire on disc or record - leaving aside for the moment the incredible sonic upgrade represented on these Original Source LPs?

Well, I hope I’ve answered part of that question in my account of how temperamentally and aesthetically suited to Karajan these works were. But there are some other elements at play here.

Sticking with Karajan himself for the moment... Lest we forget, he was first and foremost a man of the opera house. That’s where he spent the majority of his musical apprenticeship, it’s where he had some of his greatest triumphs - at the Vienna State Opera in the 1950s and early 60s. So he is able to bring years of experience as a pacer of musical drama and theatre to bear on works that, for all their lofty, “pure music” intentions, are suffused with drama. It’s a major part of the engine that drives them forward. Bruckner may not have written operas, but he understood how music can engage and surprise by being dramatic. Think of all those out-of-nowhere key changes, all those sudden pauses which have you sitting on the edge of your proverbial seat waiting to hear what happens next.

So many Bruckner conductors - especially today - don’t have a clue about pacing and drama. Everything is either underdone or overcooked in all the wrong places. They have no sense of tempo in either the micro or macro sense. Tempo - the pace of a performance - is incredibly important in Bruckner, as in keeping everything moving along (or indeed slowing down) relative to everything else. If you surrender to the temptation to underline a moment here, or dwell on a detail there, you run the risk of upsetting the apple cart five minutes further down the road.

The same applies to balancing the different strands and sonorities of the orchestra. The temptation is always to give the brass their head - and trust me they are more than happy to oblige.

No, no, no. Bruckner, for all his massive scale, is about pacing and keeping a sense of proportion, but also not missing the drama of it all.

But then allied to that there is also a highly sophisticated exploration of musical form going on, with complex sonata form and fugal structures binding together the more elaborate and extended movements. So you need a conductor who can really articulate that large structure, so that as a 25-minute movement ends, as the formal arc arrives at its apotheosis, you feel a sense of inevitability. Likewise, as the movement begins you need to feel that, though there is a long journey ahead of you, you are in sure and steady hands. You can take time to enjoy the details along the way while still having a sure sense of the path ahead.

All of this Karajan accomplishes. He is not alone, but he is right up there with the best.

And then there’s the Berlin Philharmonic. An orchestra that, very specifically, at this time, under this conductor, is a match made in heaven for this music. Why?

Beyond some of the qualities I’ve already mentioned, let me rely once more on Richard Osborne’s insights into the Karajan/BPO partnership. In the chapter of his Karajan biography covering the beginnings of this partnership, which began officially in 1956, Osborne starts by outlining how Karajan moved towards creating his instrument (for that is exactly how he viewed the orchestra) by refashioning the sound from the inside out, by hiring players who embodied his sonic ideals. This occasionally caused some ruckus within the orchestra’s ranks - remember the BPO was somewhat unique in that it was (and still is) self-governed by the players themselves. A dispute over the appointment of a horn player almost scuttled the whole relationship; a ghostly pre-echo of the dispute that would finally fracture the Karajan/BPO partnership for good some 33 years later, when the orchestra held firm against Karajan’s desire to appoint Sabine Meyer as principal clarinetist.

I am going to quote Osborne at length here, because he examines and elucidates - far better than I ever could - the qualities at the heart of the Karajan/BPO partnership.

Karajan recording with the Berlin Philharmonic (and choir) in the Berlin Philharmonie (Photo: DG/Lauterwasser)

Karajan recording with the Berlin Philharmonic (and choir) in the Berlin Philharmonie (Photo: DG/Lauterwasser)

Osborne:

What Karajan was seeking in this all-important process of rebuilding and renewal has been well described by [musicologist] Denis Stevens: ‘a wonderfully responsive, infinitely flexible instrument which represented the sound ideal that had coursed through his veins for decades’. But just as Walter Legge [creator of the Philharmonia Orchestra and Karajan’s old boss at EMI in London] had wanted ‘style’ rather than ‘a style’, so Karajan wanted a varied palette of sounds out of which individual performances could be developed. [A quality that is clearly audible during these Bruckner recordings; marvel at the work of the wind and brass soloists emerging from the ensemble - it’s mesmerizing. MW]

Nothing could be further from the truth than the often stated view that there was ‘a Karajan sound’ - generally characterised as being full, rich, and smooth - as opposed to a uniquely effective palette of sounds available to Karajan and the Berliners for the exploration and delineation of works from widely differing musical styles.

All great orchestra-conductor combinations develop some such sound culture. Listen to tapes of rehearsals by Evgeni Mravinsky, Karajan’s distinguished contemporary in Leningrad, and you will hear him asking time and again for ‘beautiful and meaningful sound’. Whenever Mravinsky uttered the baleful phrase ‘There is carrion in your sound’ the players looked to their jobs. Mariss Jansons, who studied with Mravinsky and later with Karajan, has suggested:

"Before any rehearsal a conductor must have within his imagination his ‘sound model’ which is then compared with that of the orchestra. Mravinsky had that awareness to the highest degree, as did Karajan. Often in rehearsal Karajan didn’t conduct. The art was to make the orchestra listen to itself. Critics sniped but, for musicians, what he did bordered on the miraculous".

Osborne:

The argument over sound is a matter of aesthetics though, like the parallel issue of ‘perfectionism’, it is all too rarely pursued with any real philosophical rigour. Phrases such as ‘the cult of the beautiful’ or the ‘cult of perfection’ have tended to be used, in Karajan’s case, simply as terms of disapprobation. The fact is, any form of aesthetic purism tends to upset those who prefer the artistic experience to be rooted in graspable reality…

The visceral power… of the Berlin Philharmonic sound is something that can be traced back, through Furtwängler, to Nikisch’s time. [Arthur Nikisch was one of the founders of modern conducting, a Principal Conductor of the BPO, with whom he made one of the first recordings of a complete symphony, Beethoven’s 5th, in 1913 - MW]. Karajan inherited the sound, much as a son might inherit acres of arable land. He also inherited a state of mind, a temperamental predisposition deep within the orchestra’s collective unconscious. As the critics had noticed in Salzburg in 1957, the Berlin style is full-bodied, fiery, and physically intense. Film footage reveals how the renewals of the early 1960s had made this an even more marked feature of the style. [Music critic] Neville Cardus would describe it thus:

"The playing throughout the evening was truly superb, every instrumentalist bowing and blowing and thumping as though for dear life. The violins waved and swayed like cornstalks in the wind. The drummer, white haired, might have been a conjuror drawing rabbits from his instrument’s interior. One ‘cello player, at least, swept his bow with so much passion that he seemed likely to roll off the platform. Every note had vitality, yet every note was joined to all the others. There were no tonal lacunae, not a hiatus all night. We could hear things in the score which usually we are obliged to seek out by eyes reading the score. Phrase ran beautifully into phrase, viola took on from violin, ‘cello from viola without an obvious ‘join’. Woodwind choired, perfectly blended. The violins were alternately warm and brilliant." (from a review of Karajan and the BPO’s complete London Beethoven cycle in the Manchester Guardian, 17th April, 1961).

You will hear these all qualities throughout the Bruckner set, amplified by the new hyper-detailed, three-dimensional sonics delivered by the EBS team, in which every note of what is happening in every section of the orchestra is clearly audible even in the loudest tutti. Incidentally, the BPO still exhibits the physicality described above, even in baroque music - check out any of the videos on the BPO’s Digital Concert Hall streaming service.

Osborne:

Karajan believed that the mark of a great - as opposed to good - orchestra lay in its ability to take wing in performance, to move and change direction, independent of the conductor: like a flock of birds working on its own independent radar. It is a distinction that, as far as I know, no other conductor has made in quite the same way. Though Karajan’s methods were grounded in the best practice of the old masters, there were elements in his thinking and approach which owed much to his quasi-mystical belief that music inhabits a realm apart, born of the real world but ultimately detached from it.

Indeed.

Plus - read this bit again:

"…his quasi-mystical belief that music inhabits a realm apart, born of the real world but ultimately detached from it…"

Words that could equally apply to Bruckner’s music. No wonder there is such a strong connection between Karajan and Bruckner, as evinced thrillingly over and over again in these legendary recordings.

But what, exactly, is so special about this new vinyl release, and why does it get closer to - and convey more of - the heart of the symbiosis between Bruckner and the Karajan/BPO partnership than any previous version on vinyl or CD - or even SACD?

In Part 2 of this extended look at the new Original Source vinyl release of Karajan’s Bruckner cycle, we hear from Rainer Maillard about the history of the DG sound and engineering department, and the ways in which he and his colleague, cutting engineer Sidney C. Meyer, set about revitalizing the master tapes for a new generation of listeners, and in the process made history in the world of AAA-mastered vinyl reissues.

Stay tuned…

ebs.jpg)

And while you wait, here is a fascinating interview with Sir Simon Rattle, who worked with Karajan at the Berlin Philharmonic before he himself took up the reins of Principal Conductor from 2002 to 2018.

You can read Part 2 here, and Part 3 here).

FURTHER WATCHING:

Interview with conductor Christian Thielemann:

Memories of Leon Spierer, Concertmaster with the BPO in 1963:

This fascinating film about Karajan and the great violinist Yehudi Menuhin, made by the renowned director Henri-Georges Clouzot (The Wages of Fear), who collaborated with the conductor on several outstanding concert films):

One of Clouzot's films:

More about the Salzburg Easter Festival, created by Karajan:

Karajan conducts Bruckner's 8th Symphony with the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra:

FURTHER READING:

"Herbert von Karajan: A Life in Music" by Richard Osborne (Chatto and Windus, 1998)

"Conversations with Karajan" by Richard Osborne (Oxford, 1989)

.png)