Karajan, Bruckner, and the Next Generation of Deutsche Grammophon’s Original Source Series - Part 2: “Back to the Future” - Evolutions and Revolutions in the Science and Art of Recording and Vinyl Mastering

A Deep Dive into the History and Technology behind this Epic AAA Reissue, mastered and cut directly from the 8-track master tapes

TOWARDS A RECORDING AESTHETIC: THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE DEUTSCHE GRAMMOPHON SOUND

Before we get into an examination of the many challenges and innovations encapsulated by this new Original Source vinyl reissue of Karajan's Bruckner cycle, I asked Rainer Maillard of Emil Berliner Studios to talk about the history leading up to the original sessions, specifically in relation to the evolution of DG’s approach to recording.

“If you want to talk about the sound of the first release of these Bruckner symphonies, you have to assess the work of the sound engineer Günter Hermanns. Why, almost 50 year later, is there so much room for improving the sound so dramatically?

“To answer this question, you have to understand the context within which these recordings took place. You have to understand where these recordings stand within the history of DG and the career of Hermanns.

"After the catastrophes of Nazi Germany and the aftermath of the Second World War, DG took the bold decision to make a new start. They had already become the property of Siemens [one of Europe’s most prominent manufacturing companies] in 1941. It turned out to be a lucky circumstance that Ernst von Siemens, a grandson of the company's founder Werner von Siemens, was willing to make great efforts to reorganize DG. As a member of the Siemens family, he was not only in a powerful position within the Siemens Group, but he was also a great lover of classical music, with worldwide contacts to the most important musicians of his time.

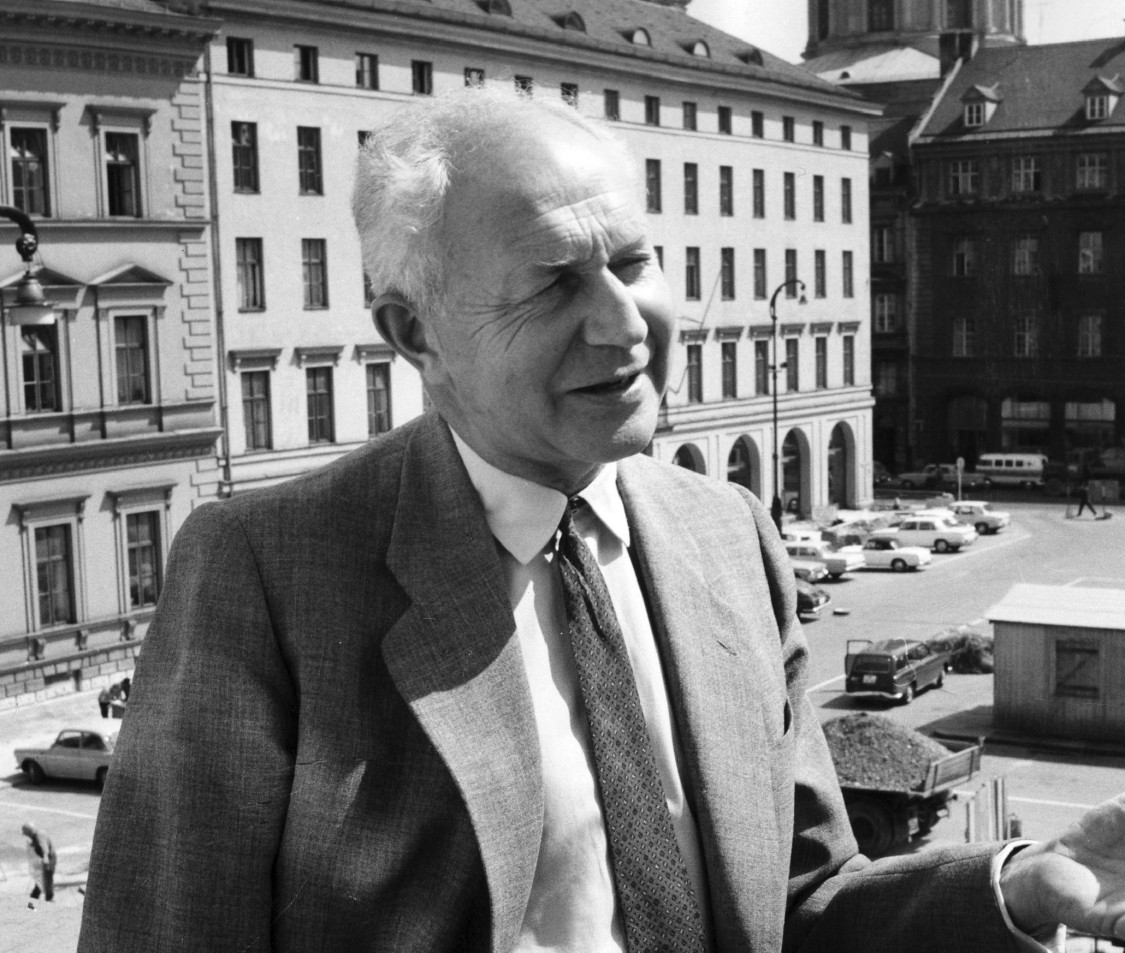

Ernst von Siemens

Ernst von Siemens

“Ernst von Siemens made several ground-breaking decisions. First, he decided to use the Deutsche Grammophon brand only for classical music (which was very much in line with his own preferences). Pop music was now released under the Polydor brand. Other labels such as DECCA published all types of music under one label.

“Since DG's reputation was in a shambles after the war, and international artists were under contract with other labels, the company focussed purely on technology for the time being. The goal was to produce the best pressings in the world in order to quickly catch up with the international competition.

“Due to a lack of international artists, new releases tended to focus on repertoire rather than interpretations. The sub-label Archiv Produktion, which focused on Baroque and earlier music, was founded with this emphasis in mind.

“It was only with the slow onset of success in the late 1950s that internationally recognized musicians - such as Karajan - would be associated with DG again.

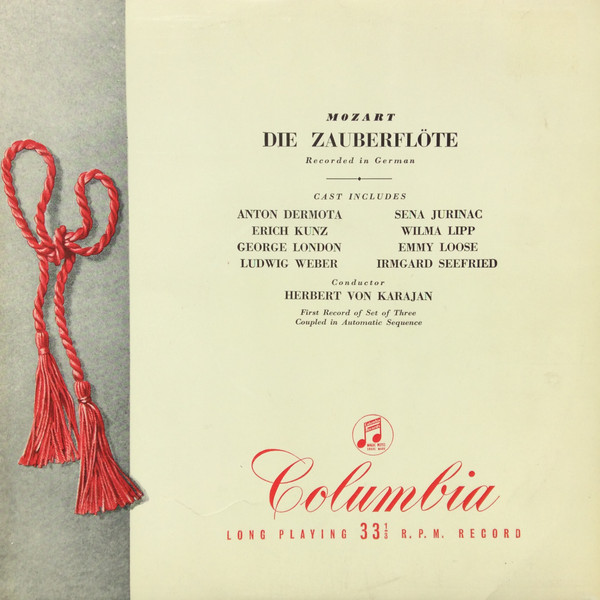

“In the summer of 1951, Ernst von Siemens invited Herbert von Karajan, who was under contract with Columbia at the time, to his home. Siemens played him the latest DG pressings and compared them with Columbia LPs. Karajan was impressed by the technical quality of these DG LPs (and shocked by the lesser quality of his own Columbia LPs).

Karajan's famous 1951 Recording of Mozart's Magic Flute - possibly one of the records Siemens played the conductor during their meeting

Karajan's famous 1951 Recording of Mozart's Magic Flute - possibly one of the records Siemens played the conductor during their meeting

"Karajan was not so impressed by the actual musical interpretations on DG. At this time, Siemens did not yet mention a contract offer from DG to Karajan. However, this meeting demonstrates the great influence Ernst von Siemens had on the development of DG. Being both a profound connoisseur of classical music and an expert in technical matters, he helped to bring the most important artists back to DG.

“Ernst von Siemens also played a key role in the founding of PolyGram, recognizing very early on that only through international cooperation could DG achieve its full potential in the global market. By positioning DG so prominently he could win over the most important interpreters of classical music and bring them to the label.

“By the 1970s, the situation had changed completely. DG was now a renowned classical label with strong links to the production of high-quality pressings. It was considered the label of the stars. And Herbert von Karajan - now a DG artist - represented the label like no other conductor.

dgg.jpg) Günter Hermanns consulting a score while mastering Karajan's recording of Bruckner's 6th Symphony

Günter Hermanns consulting a score while mastering Karajan's recording of Bruckner's 6th Symphony

“Günter Hermanns joined DG in 1949 as a technician in the workshop. But he got the chance to move into the recording department as an assistant. Hermanns’ first opportunity to work as a sound engineer came during a Ferenc Fricsay session. Fricsay was notorious for being very particular about getting the sound right. DG producer Hans Weber had to conduct while Fricsay sat down at the mixing desk together with sound engineer Werner Wolf. On this particular occasion, they couldn't achieve a satisfying result and so Günter Hermanns took over the mixing desk from Mr. Wolf. Hermanns’ great talent was immediately apparent: he was able to quickly understand and realize the artists' ideas.

"Like many of his generation he came into the business without a formal engineering training. He learned “on the job”.

“Hermanns was extremely reliable and was very good at working with the artists. He was able to make them happy, so they trusted him. There are many statements from Fricsay, Karajan, Mutter, Pollini and others saying the same thing: they trusted his opinion about sound.

“If you look at DG session photos from that time, you can see not only the recording producer but also the sound engineer sitting at the desk with the score. The primary goal was to realize the sound of the score in a recording. Not only did the actual sound have to be right, but also the balance between the instruments.

![Tonmeister Hans-Peter Schweigmann [4], recording producer Werner Mayer [5] and Edith Mathis at the new PolyGram module mixer during a recording session in Munich 1974.](/assets/csm_ohne_titel-29_a5388b94b3.jpg) Tonmeister Hans-Peter Schweigmann, recording producer Werner Mayer, and soprano Edith Mathis at the new PolyGram module mixer during a recording session in Munich 1974. Note the score in Schweigmann's hands, following in the house tradition discussed by Maillard above. (Photo: Emil Berliner Studios)

Tonmeister Hans-Peter Schweigmann, recording producer Werner Mayer, and soprano Edith Mathis at the new PolyGram module mixer during a recording session in Munich 1974. Note the score in Schweigmann's hands, following in the house tradition discussed by Maillard above. (Photo: Emil Berliner Studios)

“This was the time when DG began to develop multi-microphone recording techniques, an approach that fit well with this overall approach to recording. The performers' desire to be able to adjust the balance between all the instruments for certain passages was much easier to achieve with spot microphones than with a main microphone assembly alone. It often turned out that although the balance was generally very good with main microphones only, one instrument might sound too quiet in certain passages. If you placed it closer to the main pair, its level might be appropriate in certain passages, but not so much in others.

“Since DG claimed to be the label of the stars, the recording teams put great emphasis on ensuring that the musicians' wishes regarding the sound of their interpretations were met. And Günter Hermanns was able to provide solutions like few other engineers at the time.

“Achieving an audiophile sound image, as is the goal of vinyl today (or other classical labels during that time), was not the primary goal for Hermanns; nor was it his colleagues’ goal back in those days.

“Everyone perceives sound differently. However, I have found that musicians often judge their recordings according to completely different criteria than the listener at home. The listener at home rarely listens to an LP with the score. It seems to me that they enjoy music in a different way than the musicians themselves. However, creating sound images which primarily pleased the listener at home was not the main goal for DG engineers. The artists and their wishes came first. That was the DG philosophy. Other labels had their own specific history, and therefore developed different approaches to their recording techniques.

Herbert von Karajan and recording producer Hans Weber in the Jesus Christus Kirche in Berlin (Photo: EBS)

Herbert von Karajan and recording producer Hans Weber in the Jesus Christus Kirche in Berlin (Photo: EBS)

“By the time the Bruckner recordings began, Karajan’s previous producer, Hans Weber, had stopped working with the conductor, whom he felt was cutting him out of the creative process, ignoring his input. As Michel Glotz [Karajan’s agent and new producer] lived in Paris and - as far as I can tell - was not involved in perfecting the details, Hermanns took over many aspects of communication between the maestro and DG which normally would be handled by the recording producer. Hermanns handled all this very well: that’s why he was so important to HvK and DG.

“Since he worked with their best-selling artist (HvK) for so many years, Hermanns seemed to be the most popular DG engineer during this time. But personally I feel that others were putting in more work to create a more “audiophile” sound. Hans-Peter Schweigmann, Klaus Scheibe and Klaus Hiemann all undertook many experiments, and developed new ideas for improving sound without forgetting the importance of illuminating the score. (Of course I was not there at the time - this is just my conjecture from listening to the tapes and asking questions of those who were there etc.).

“For me it is a difficult question as to whether there is a specific DG-sound. The multi-microphone technique gave the sound engineers much freedom to create their own specific sound. Recordings from different DG engineers sound quite different from each other. I could immediately identify a recording by Hermanns in comparison to Schweigmann, which makes it difficult to speak about a specific DG sound at all. But all engineers worked with a somewhat similar approach and a score on their mixing desk.

“The existence of the original multitrack recordings from the 1970s - fully edited into “master tapes” - allow us to respectfully set Hermanns’ original mixes aside and create new ones today. This is a challenge, because the original releases were approved by the artists at the time and were exactly what they wanted. And at that time DG also thought those recordings represented the state of the art.

“But with these great multitrack masters we are now in a position to mix with a more “audiophile” result in mind. We are able to elevate these great recordings to a higher level of sonic excellence, higher than anything Hermanns imagined he could create.

“But remember - the only reason we are able to do this at all is because what is on the original multi-track tapes is of such a high level to start off with.”

Specially Modified Studer A80 for Playback of 8-Track Master Tapes (Photo: EBS)

Specially Modified Studer A80 for Playback of 8-Track Master Tapes (Photo: EBS)

THE NEXT GENERATION OF THE ORIGINAL SOURCE SERIES: RE-IMAGINING THE SONICS OF THE KARAJAN-BRUCKNER CYCLE

It’s been just over a year since the first releases in Deutsche Grammophon’s Original Source Series of vinyl AAA reissues came to market, and I think it’s reasonable to say that the series has been an unqualified success. Regular readers of this site will have no doubt followed the (at times) breathless coverage afforded by myself and Michael Johnson, let alone the plaudits lavished on the series elsewhere.

For me one of the core achievements of these reissues has been how Maillard and his colleagues at EBS and Optimal have refined what is essentially old technology (vinyl mastering and cutting) to the nth degree, in tandem with building new equipment to allow mixing and mastering directly from multitrack tapes, all in the service of revivifying DG’s celebrated and historically significant back catalogue for a new generation of listeners. In the process they have re-defined the DG “sound” of the 1970s, elevating it to a truly "audiophile" level. As Maiilard states above, it couldn't have happened if what was on the tape wasn't of a pretty high quality to start off with.

The result has been many more audiophiles and general listeners taking notice of classical music once more - or indeed for the first time - which is a very good thing indeed.

So when it came time for DG to think of something they could do to suitably celebrate the bicentenary of Anton Bruckner’s birth this year, it was probably a bit of a no-brainer to think about reissuing Herbert von Karajan’s legendary cycle with the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra, recorded and released in the mid-1970s to early 80s, as part of the Original Source series.

Just one problem. Unlike the earlier releases in the Original Source series, which were all mastered and cut directly from 4-track master tapes, the Karajan Bruckner cycle existed on 8-track master tapes and, in the case of the first three symphonies, on digital multi-track masters.

Typically, Rainer Maillard and his colleague at Emil Berliner Studios, Sidney C. Meyer, saw this less as a challenge and more as an opportunity.

Why not mix, master and cut directly from the 8-track masters?

Why not indeed? Minor detail - this had never been done before, by anyone, anywhere.

The story of how Maillard and Meyer overcame the obstacles inherent in mastering from 8-track, and in the process broke new ground in the mastering and cutting of AAA vinyl (and also revitalized the sonically compromised digital recordings of symphonies 1-3) is a story of imagination meeting engineering ingenuity, and the results are truly remarkable.

Sidney C. Meyer (l.) and Rainer Maillard in the Room Where Vinyl Magic Happens - note the Yellow Passive Mixer on the left built specially for this project (Photo: EBS)

Sidney C. Meyer (l.) and Rainer Maillard in the Room Where Vinyl Magic Happens - note the Yellow Passive Mixer on the left built specially for this project (Photo: EBS)

If you think you knew the “sound” of the Karajan/BPO partnership in its 1970s heyday, think again. The new LPs wipe away years of sonic shortcomings and accretions derived from questionable mixing and mastering choices, and highly compromised manufacturing choices made by DG (see my original article on the Original Source Series for more detail on this). To listen to these new records is to travel back in time, taking you as close as I imagine it’s possible to go to what it must have been like to hear conductor and orchestra in the Berlin Philharmonie “live” back in the day. Beyond the sheer thrill of hearing this epic music presented so immersively, there is a sense of the technology so accurately (but also organically) capturing what was played at the sessions that the technology itself disappears, leaving us with merely the music itself and the intention of the performers. This has long been Maillard’s credo in all his work - to allow the music, the performance - to emerge unfiltered, and the reason for his passionate support of the Direct-to-Disc process as the ultimate way to capture a performance on vinyl. As you will read, the process he ended up adopting for this Karajan set had much in common with the D2D methodology.

I would advise anyone reading the following who hasn’t already read Tracking Angle’s previous coverage of the Original Source series to at least peruse my article about the first releases in the series, because it covers a lot of the basic methodology that was expanded upon by Maiilard and Meyer for the Karajan/Bruckner set.

Part of the strength and integrity of Rainer Maillard’s whole approach to the Original Source Series derives from his decades of experience at DG, beginning in the 1980s. When approaching this whole project he was informed as much by what had gone before - historically, aesthetically, and engineering-wise - as by what he envisioned moving forward. The account that follows draws on his fascinating - and detailed - essay included in the booklet for the new box, as well as a series of answers he provided to further questions I had.

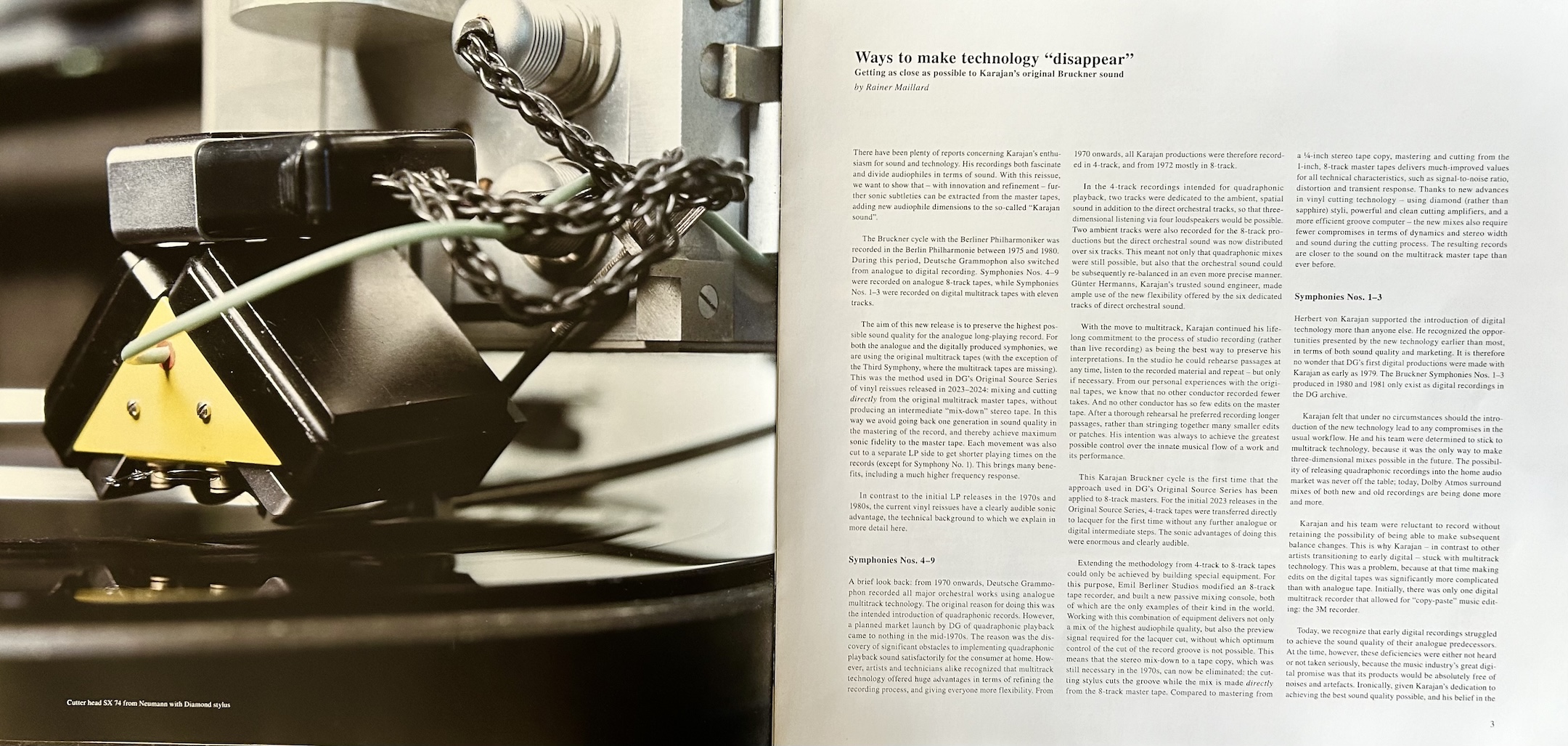

Maillard's Essay in the Bruckner Box Set Booklet

Maillard's Essay in the Bruckner Box Set Booklet

To briefly recap: there are several things that made the first rounds of releases in the Original Source Series so distinctive.

Firstly, all the records were mixed, mastered, and cut directly from the 4-track master tapes, with maximum fidelity and bandwidth, achieved by Sidney Meyer’s superior cutting skills and a close collaboration with Thorsten Megow at the pressing plant, Optimal Media. There was no intermediate mix-down to stereo.

Secondly, the original recordings featured two tracks of ambient room sound, made at the time of the original sessions for a putative quadraphonic release that never materialized, owing to (in DG’s opinion) insurmountable technical and commercial challenges. In mixing and mastering the new Original Source LPs, Maillard was able to mix these “surround” tracks deftly with the direct stereo sound, thereby creating a more three-dimensional, almost holographic, soundstage than the one you generally hear on regular stereo recordings, even the very best ones. Now sometimes, on certain recordings, I felt the ambient information threatened to overwhelm the direct sound, but on the majority of the records the increased detail revealed was perfectly complemented by an enveloping and more realistic (and integrated) hall acoustic. (This whole issue of achieving a good balance between these three elements - the hall acoustics, the orchestra and added reverberation - plays a major role in both the history of these Bruckner recordings and also in the decision process for achieving the ideal remix and remastering of this Bruckner set). Moving beyond 4-track into 8-track recording in 1972, DG continued to record two tracks of ambient sound for all its projects, so in mixing this Bruckner set Maillard still had that extra spice to add to the sonic palette.

From Rainer Maillard’s essay in the box:

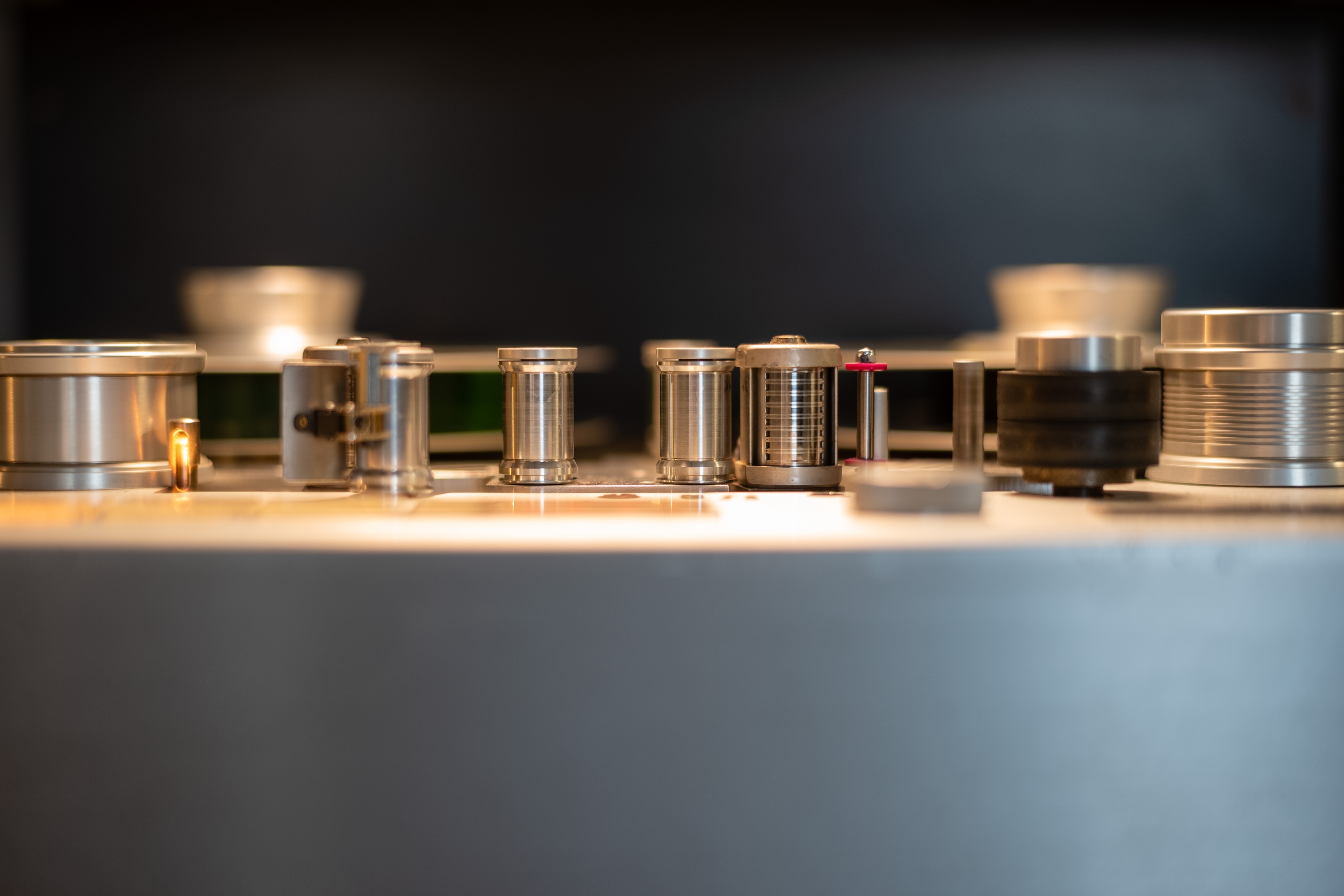

“Extending the methodology from 4-track to 8-track tapes could only be achieved by building special equipment.

ebs.jpg) Modification of Studer A80 in progress (Photo: EBS)

Modification of Studer A80 in progress (Photo: EBS)

"For this purpose, Emil Berliner Studios modified an 8-track tape recorder, and built a new passive mixing console, both of which are the only examples of their kind in the world.

ebs.jpg) Rack Mount Component of Specially Designed Passive Mixer Under Construction (Photo: EBS)

Rack Mount Component of Specially Designed Passive Mixer Under Construction (Photo: EBS)

"Working with this combination of equipment not only delivers a mix of the highest audiophile quality, but also the preview signal required for the lacquer cut, without which optimum control of the cut of the record groove is not possible. This means that the stereo mix-down to a tape copy, which was still necessary in the 1970s, can now be eliminated: the cutting stylus cuts the groove while the mix is made directly from the 8-track master tape. Compared to mastering from a ¼-inch stereo tape copy, mastering and cutting from the 1-inch, 8-track master tapes delivers much improved values for all technical characteristics, such as signal-to-noise ratio, distortion and transient response. Thanks to new advances in vinyl cutting technology - using diamond styli instead of sapphires, powerful and clean cutting amplifiers, and a more efficient groove computer - the new mixes also require fewer compromises be made in terms of dynamics and stereo width and sound during the cutting process. The resulting records are closer to the sound on the multitrack master tape than ever before.”

I asked Rainer to expand on these comments for this article:

“When, in 1972, DG switched from 4-track (with 2 tracks for room ambience) to 8-track (still with 2 tracks for room ambience), these 8-track tapes were never intended to be used directly for mastering and disc cutting. They would make a stereo and a 4-track quadraphonic mixdown (as you can read on the tape boxes). [In the end, DG never released any quadraphonic records, unlike EMI and CBS/Columbia - MW].

ebs.jpg) Box containing Master Tape for First Movt. of Bruckner's 8th Symphony (Photo: EBS)

Box containing Master Tape for First Movt. of Bruckner's 8th Symphony (Photo: EBS)

“The good thing is that DG learned from the past. The engineers knew you must create and retain an original format that was the same as the recording itself in order to be able to graft it onto the future, so to speak; to future-proof it. Here we must mention the vision of the head of the PolyGram technical department, Peter Burkowitz. Without the 100% support of this “boss” this never would have happened for the more than 1000 original master tapes produced during this time. Splicing the multitrack, and then subsequently creating downmixes, meant a huge amount of extra effort over the years.

Edit on the Original 8-Track Master Tape. It was only because these Multitrack Masters were "complete documents" - fully edited - that Maillard could mix and master directly from them. The jagged "cut" prevents unwanted drop-out etc. from marring the edit. (Photo: EBS)

Edit on the Original 8-Track Master Tape. It was only because these Multitrack Masters were "complete documents" - fully edited - that Maillard could mix and master directly from them. The jagged "cut" prevents unwanted drop-out etc. from marring the edit. (Photo: EBS)

"I am not sure this kind of investment in the future would happen nowadays. There are so many controllers and managers working for the label (and no more singular technical director with the necessary influence) that we have to be very glad that this happened in the past, at least. The past and the original master tapes have survived together.

“It was last year when I first had the idea of using the 8-track masters directly to remix, master and cut from.

“I was familiar with many of these 8-track masters since my first days working at DG in 1985 in the summer holidays, when I was a student. Over subsequent years I did many remasterings and therefore knew which challenges would emerge. First, we would have to mix in real time without any interruption. With mixdowns in the past, the engineers worked in sections and than made edits to glue every mixdown take together to arrive at a new “master”.

“Because Emil Berliner Studios had so much experience working with Direct-to-Disc recordings - mixing, mastering and cutting, always without the ability to stop - we felt ready to do a mix and master without any interruptions.

“The more complex challenges lay in the technical aspects. This was the challenge: how to build the machines we would need in such a way that the workflow would enable us to do what was needed. There were two main challenges here:

“1. Studer never built an 8-track tape machine with a preview head - essential for disc cutting.

"2. We could not find any mixing desk on the market which was small enough so that it would fit on our Neumann Mastering desk, and have at least 16 channels (two times 8-track for modulation and preview) plus 4 output channels, and also accommodate our ideas for how we wanted to achieve all this.

“So, it quickly became clear that we would have to build our own gear.

“Our Studer was modified by Peter Dietz, a wonderful engineer with tons of experience in analogue equipment. But also we needed custom metal work for the Studer modification, none of which had ever been built before. We found a gentleman called Gustav Hassenpflug, an 85-year old mechanic, who built all the small parts we needed in his workshop.

“Peter Dietz made the drawings and Gustav built the parts. This turned out to be more complicated work than we originally expected (and, not surprisingly, cost us three times more than we had anticipated).

Note the fact that the mixer is in the same yellow as the iconic DG cartouche - a lovely nod to the heritage of the DG label (Photo: EBS)

Note the fact that the mixer is in the same yellow as the iconic DG cartouche - a lovely nod to the heritage of the DG label (Photo: EBS)

“The passive mixer was constructed by myself and was built with the help of Matthias Laufer. Why passive? Because it is the best compromise for maintaining quality while keeping down costs.

“Passive mixing means you have no active device in the signal path. No transistor, no tube, not even a condenser: there is only one resistor in the path just before the mixing point. This means there is no possibility for change in, or colouration of, the sound (whether desired or not). It is a very “purist” approach.

“Due to the damping effects of a passive mixer, you normally have an amplifier at the output stage to bring up the level (like we have on our vintage mixing desk). This is not the case with our passive mixer. Since the tapes had been magnetized with “hot” levels, and because our mastering desk already has an input amplifier, we were very happy to be able to skip this output amplifier.

"There are always two sides to a coin, however. Passive mixers aren’t flexible. They do not have any panorama setting, any filters, any compressors. Sometimes, there was a need for using some of these additional effects, even when we were working with tapes that had been recorded in such a purist manner.

“So we added to our passive mixer an insert for effects, to be used only if absolutely needed.

“It is the big clue to the secret of our mixer: it was constructed in such a way that that under each single fader the modulation and the corresponding preview signal is to be found. This is what no other existing mixing desk could achieve: mixing (while monitoring) the modulation signal, while also mixing the corresponding preview signal et al, which comes 900ms earlier.”

ebs.jpg) (Photo: EBS)

(Photo: EBS)

Maillard’s essay in the set’s booklet addresses head-on many of the assumptions and mistruths that have, over the years, attached to the whole notion of the so-called “Karajan sound”. Much of what has been said and written has, I believe, derived from some of the prejudices and innate hostility to all-things Karajan that has been around since the beginning of his career and persists, remarkably, even today. On the one hand, serious critical examination and negative judgments of his interpretations and recordings are of course justifiable, if they are cogently argued; but on the other hand, statements pertaining to Karajan’s proclivity for “fiddling with the mixes” and overriding his engineers have often been mere code for saying he didn’t know what he was doing or, more disturbingly, “he was a control-freak, a Nazi, so what do you expect?”.

(Leaving aside the whole question of whether there is any such thing as a conductor who isn't a “control-freak”, the Nazi issue in relation to Karajan is a complicated one, understandably loaded, but one that comes up regularly with arguments derived more often than not from an imperfect knowledge and/or imperfect regurgitation of the facts. This issue simply will not die, or at least be put into historical perspective, even in the face of substantial documentary evidence of both Karajan's reluctance to join the Nazi Party, and also the Party's hostility towards him; see my comments addressing this in the first of these three articles. If you want to get what I have found to be the most balanced, cogent account of all this, read Richard Osborne's book).

-siegfried-lauterwasser-dg.jpg) One of the reasons the idea arose that Karajan "tinkered" with his recordings - a notion which lacks substantial evidence - may be that he loved being photographed at mixing consoles (Photo: DG/Lauterwasser)

One of the reasons the idea arose that Karajan "tinkered" with his recordings - a notion which lacks substantial evidence - may be that he loved being photographed at mixing consoles (Photo: DG/Lauterwasser)

In my reviews of earlier Karajan recordings in the Original Source Series made in the Jesus Christus Kirche, I tried to address some of the sonic oddities in those recordings, which were now made more evident because of the extra fidelity of the Original Source process, even as overall the recordings were also sounding immeasurably better. The more I talked to Maillard about all this it became clear that something else entirely was going on, and this is only underlined by the huge sonic upgrade in this new Bruckner cycle.

From Maillard's box set essay:

“There are many who feel that Karajan’s recordings after 1974 do not sound as good as his earlier ones, especially the digital multitrack recordings (but also some analogue 8-track ones). There has always been speculation that this was because Karajan “interfered” with the engineers’ work. The truth of what lay behind this change in the sound of his records is more nuanced and complicated than that.

Günter Hermanns - Karajan's main engineer throughout his time at DG - in the control room of Symphony Hall Boston, February 1971. (Photo: EBS)

Günter Hermanns - Karajan's main engineer throughout his time at DG - in the control room of Symphony Hall Boston, February 1971. (Photo: EBS)

“One of Günter Hermanns’ great skills was his ability to mix in real time during the recording session itself, to a very high standard. He did this because he knew that, for 2-and 4-track recordings, an edit on tape would only be possible if the balance and levels on either side of the cut matched perfectly. That’s why he did not make any extreme movements with the faders during the sessions.

“Even with analogue 8-track (and later 3M digital), Hermanns aimed to mix as much as possible during the recording sessions themselves, striving to avoid extreme changes of balance and levels. He knew there wouldn’t be an opportunity to adjust levels later on, while editing.

“With the arrival of multitrack, Hermanns experimented with working more like pop musicians and producers did: doing a lot of additional work in postproduction, after the recording sessions. He began to move faders in a more extreme way. He discussed all sound and mixing issues with Karajan during the sessions or on the phone, but, with very few exceptions, Karajan never came to the DG studios in Hanover for the final mixes. He trusted his recording team.

“In 1992, when we began remixing and remastering Karajan’s digital recordings for the Karajan Gold CD reissues, we felt we needed to adjust most of Hermanns’ original, and somewhat extreme (and not good-sounding), fader moves. We often asked ourselves if we should be doing this. Despite being retired by then, Hermanns himself joined us sometimes: he gave his approval for what we were doing.

“Providing you have miked the musicians well, and have the balances correct, leaving the faders in a similar position throughout the mixing process results in a much more coherent sound; a sound that is, perhaps, closer to how our ears hear the music in a concert hall (or a recording studio), where no-one is adjusting the levels or balance apart from the conductor and the musicians. (The goal for us is to find ways to use technology to make the technology "disappear").

“This has always been the defining philosophy of the Original Source Series: to reproduce as closely as possible the original intent of the musicians and engineers as preserved on the original master tape.”

TAMING THE BERLIN PHILHARMONIE "SOUND"

The Berlin Philharmonie

The Berlin Philharmonie

The other important element that had to be accounted for in restoring these Bruckner recordings to the highest fidelity to the master tapes was the “sound” of the Berlin Philharmonie itself. Karajan had only recently started recording in the BPO's home, and doing so raised all kinds of issues that were not easy to resolve.

The Philharmonie, designed by renowned architect Hans Scharoun, was an early example of the new “in the round” approach to the concert hall space. As classical music found itself increasingly under attack as an “elitist” art-form in the 1960s, the idea was to create a more egalitarian experience for the audience, which would surround the musicians, with listeners in the cheaper seats remaining closer to the stage by virtue of the circular design. This was in sharp contrast to the more hierarchical approach of traditional halls like Boston’s Symphony Hall and the Musikverein in Vienna, where you’d get the aristocrats showing off their finery in the posh seats near the stage, while those plebs considered less “worthy” would be relegated to the back of the hall. (I exaggerate, but you get my drift).

Interior of Berlin Philharmonie (Photo: Pierre Adenis)

Interior of Berlin Philharmonie (Photo: Pierre Adenis)

Well, this is a nice concept, and it has become a dominant mode in concert hall architecture since the debut of Scharoun’s striking Philharmonie design in 1963.

However, there was a problem. One of the reasons why concert halls had hitherto tended to adopt the same “shoebox” design of Boston’s Symphony Hall etc. was simply because it was the easiest, and best, way to ensure top-notch acoustics - which, after all, is the most important thing to get right in a concert hall.

The acoustics of the Berlin Philharmonie were, by all accounts, problematic from the start. I am no expert in this field, but I imagine that without access to the kind of sophisticated computer programs which today’s acousticians like Yasuhiso Toyota were able to use when creating halls like the spectacular Walt Disney Hall here in Los Angeles, designing the acoustics of the Berlin Philharmonie was more of a shot in the dark.

Opening Concert of the Philharmonie in 1963 (Photo: Reinhard Friedrich)

Opening Concert of the Philharmonie in 1963 (Photo: Reinhard Friedrich)

Even though Karajan and the Berlin Philharmonic began playing concerts in “their” hall in 1963, they continued to record in the Jesus Christus Kirche for the next decade. The first recordings made in the Berlin Philharmonie included those made early in this Bruckner cycle - Symphonies Nos. 8 and 9.

Those first records made in the Philharmonie got very mixed reviews on their sonics, not dissimilar to the albums recorded in London’s sonically dodgy Barbican Hall by the London Symphony Orchestra on its own nascent label - LSO LIve - in the early 2000s. They tended to sounded very dry indeed.

A good example of this would be Karajan’s 1976 recording of Tchaikovsky’s 5th Symphony, a powerhouse performance where you feel like you are sitting in the middle of the orchestra, the acoustic is so dry. However, on the subsequent vinyl box set there seems to be more reverb. On the EBS remixed/remastered SACD set there’s clearly been a change in the mix of the orchestra itself - an improvement - but in some ways the reverb here (added no doubt in post) detracts from the immediacy that I had come to love on the original LP.

Now, the original LPs of this Bruckner cycle (all of which I bought as they were first released) shared with that Tchaikovsky recording a drier (though not as dry) acoustic, and also a more immediate, visceral orchestral sonority (albeit without much bloom) than Karajan's earlier recordings made in the Jesus Christus Kirche. Why?

Well, in part, as Maillard speculates in his fascinating behind-the-scenes video made specially for this release (I will post the link when it becomes available) this could be because the Philharmonie (unlike the Jesus Christus Kirche) lacked its own “echo chamber” which engineer Hermanns could use during the sessions. He was reliant on the echo chamber at DG’s new headquarters, or electronic devices, and as we now know he was not averse to fiddling with the mixes in subsequent iterations of his recordings.

Let’s go back to the fundamentals of the Philharmonie itself. You can clearly see in photos from different eras of the hall that various acoustical panels have been introduced over the years to improve the acoustics. Nevertheless, the acoustics at the time these Bruckner records were made were more challenging. So, to optimize the sonics, Maillard had to tackle the issue of the Philharmonie “sound” head-on. Fortunately, his own personal history with the hall put him in a unique position to make the right judgment calls.

Exterior of the Berlin Philharmonie in 1964. Due to its location near the Berlin Wall, there were few buildings near the Hall - a very different situation to today, when it stands at the new, post-Cold War center of the city. (Photo: Reinhard Friedrich)

Exterior of the Berlin Philharmonie in 1964. Due to its location near the Berlin Wall, there were few buildings near the Hall - a very different situation to today, when it stands at the new, post-Cold War center of the city. (Photo: Reinhard Friedrich)

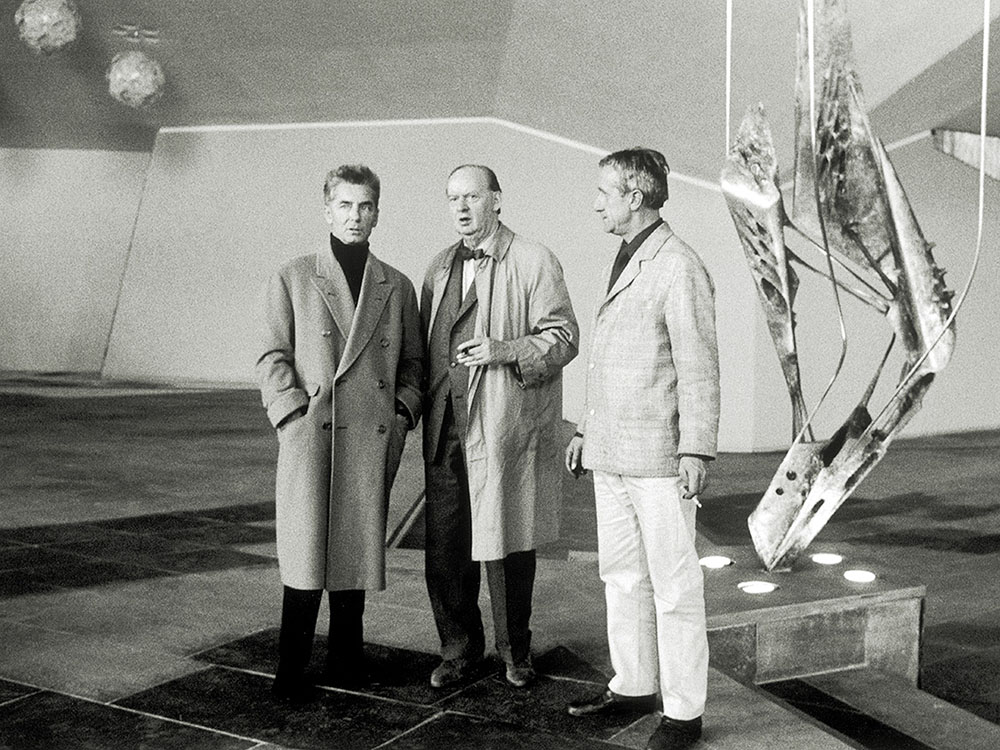

Karajan (l.) with architect Hans Scharoun and sculptor Bernhard Heiliger (r.) in the foyer of the Philharmonie in 1963 (Photo: Landesarchiv Berlin)

Karajan (l.) with architect Hans Scharoun and sculptor Bernhard Heiliger (r.) in the foyer of the Philharmonie in 1963 (Photo: Landesarchiv Berlin)

Maillard:

“I grew up in Berlin and, at the age of 16, I started going to concerts at the Berlin Philharmonie with a friend, whose father played double bass in the orchestra. We found ways to get into the hall without tickets. I found my own favorite “spot”. It was behind the last row in Block B, where the architect Hans Scharoun had built an acoustic stone panel which could be used as a small seat. From there I listened to hundreds of concerts, all from that same spot!

“This influenced my whole life. I remember when I first heard a concert at the Musikverein in Vienna: I thought the sound was not right! I had to learn that different halls all have all their different sounds, all with their own advantages and disadvantages.

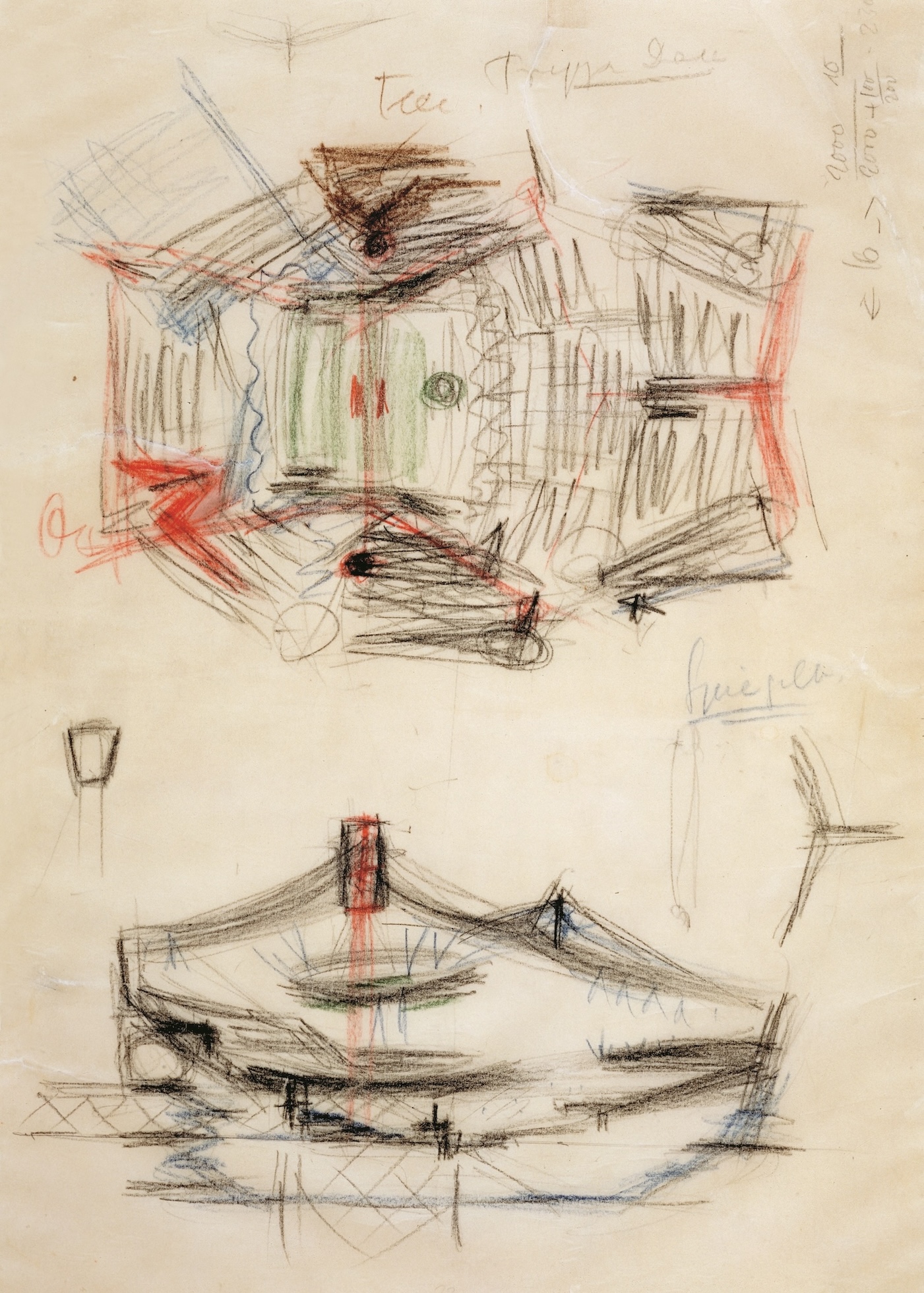

First sketches by architect Hans Scharoun of the interior and exterior of the Philharmonie (reminiscent - or rather prescient - of Frank Gehry's first sketch of Disney Concert Hall on a napkin) (Photo: Archive Akademie der Künste, Berlin)

First sketches by architect Hans Scharoun of the interior and exterior of the Philharmonie (reminiscent - or rather prescient - of Frank Gehry's first sketch of Disney Concert Hall on a napkin) (Photo: Archive Akademie der Künste, Berlin)

“For me the sound of the Berlin Philharmonie is “right” (because this sound is burned into my brain as a reference for all others). But I know other listeners with different “reference halls” in their minds would hear more disadvantages than me. Those disadvantages would include a little lack of reverberation, and, like the Jesus Christus Kirche [where Karajan recorded for decades] there is a shorter reverberation time in the low end - unlike Boston Symphony Hall and the Musikverein. For me this is not really a disadvantage (as it can be for others) because I know this is coupled directly with a big advantage: a greater transparency!!! (And as I was trained in my listening and sonic ideals at the Berlin Philharmonie, I always love transparency).

“You can have a nice room reverb like Boston. I love it because this is what I was missing from Berlin. But again: there is a related disadvantage - a lack of transparency. This is what I guess you [ie. me, MW] were not happy with in the Holst and Strauss in the Steinberg set. [Indeed I felt there was too much hall reverberation on these two records, as you can read in my reviews of this set - MW].

“Using supplemental, artificial reverb helps us to better handle a drier acoustic, like the one at the Berlin Philharmonie. It turned out that our echo chamber at EBS (just our regular emergency stairway) fit perfectly with the Berlin Philharmonie acoustic.

The Emergency Exit Stairwell at Emil Berliner Studios, aka the Echo Chamber for the Philharmonie (Photos: EBS)

The Emergency Exit Stairwell at Emil Berliner Studios, aka the Echo Chamber for the Philharmonie (Photos: EBS)

ebs.jpg) SHHH! Vinyl Cutting In Progress!!

SHHH! Vinyl Cutting In Progress!!

"This turned out to be magic, and was not planned at all - it was simply good luck!

“Hermanns exercised good judgment when he chose to record dry and then add some reverb later to his mix. But he always used more or less the same mic setup in all the halls he recorded in, and that works better in some halls than others.”

-siegfried-lauterwasser-dg.jpg) Karajan and engineer Jobst Eberhardt (Photo: DG/Lauterwasser)

Karajan and engineer Jobst Eberhardt (Photo: DG/Lauterwasser)

For these reissues, the combination of the two tracks of room ambience (a bit of a misnomer in this case, since from a photo featured at 16:43 in EBS’s “making of” video, you can clearly see that the “surround” mics would actually be capturing a lot of direct orchestral sound, a factor that fed into Maillard’s choices in his remix), together with the echo from the stairwell at Emil Berliner Studios, results in the most natural sounding Philharmonie acoustic of any I’ve heard on recordings of this vintage.

What does this mean? Well, on the analogue sourced records in this set (Symphonies 4 - 9) you are hearing, I think, the best the Karajan/BPO partnership has ever sounded on record - or any other medium, for that matter. The drier acoustic of the Philharmonie means that all the layers and sonorities of the orchestra are captured, then revealed, with unparalleled fidelity. The enormous dynamic range (and it is enormous) emerges effortlessly, unmediated and unfiltered by fidgety fingers on the mixing board’s faders, and the whole sonic picture is beautifully blended with just the right amount of reverberation. Unlike some of the earlier Karajan recordings in the Original Source Series there aren’t odd shifts in perspective depending on volume. The orchestra is simply spread out in front of you, everything in its right place, with the gorgeous sonorities of the solo wind and brass lines emerging organically from the whole when need be, and the thunderous, gleaming and golden brass fully integrated into the whole, not sticking out like a sore thumb. Even when it gets loud, you still hear all the detail going on in those hard-working strings.

Listening to this set, for the first time I was feeling the sheer power and also finesse of the Karajan sound, as well as hearing it. This is something I’d read about in accounts of his live performances - how physical the Karajan/BPO sound was - and which I had glimpsed on certain live recordings and, to an extent, the many studio recordings that weigh down my record shelves.

But none of these give you that overwhelming visceral quality which these new Bruckner records deliver in spades.

It’s a pretty awesome thing to behold - and in your own living-room to boot!

Karajan (front left) with the Berlin Philharmonic after a performance of Beethoven's Missa Solemnis in the Philharmonie (Photo: Siegfried Lauterwasser)

Karajan (front left) with the Berlin Philharmonic after a performance of Beethoven's Missa Solemnis in the Philharmonie (Photo: Siegfried Lauterwasser)

Stay tuned for Part 3, where we hear how the EBS team managed to substantially refurbish the sonics of the three digital recordings in this cycle, and take a more detailed look at Karajan’s traversal of all nine symphonies.

NEW BEHIND-THE-SCENES VIDEO MADE BY EBS:

You can read Part 1 of this series of articles devoted to this reissue of Bruckner's 9 Symphonies, focusing on Karajan's history conducting Bruckner, here; and Part 3 here).

FURTHER VIEWING:

About the Berlin Philharmonie:

Contemporary newsreel, in German, but full of great shots of the hall.

Memories of one of the construction workers, with English subtitles:

Memories of opening night from one of the orchestra's 'cellists:

Memories of two attendees of the opening concert in 1963:

Memories of one of the staff at the opening party:

.png)