'Original Source' 2025 Wrap Up: Part I

A deep dive into the final 4 AAA Deutsche Grammophon titles of 2025

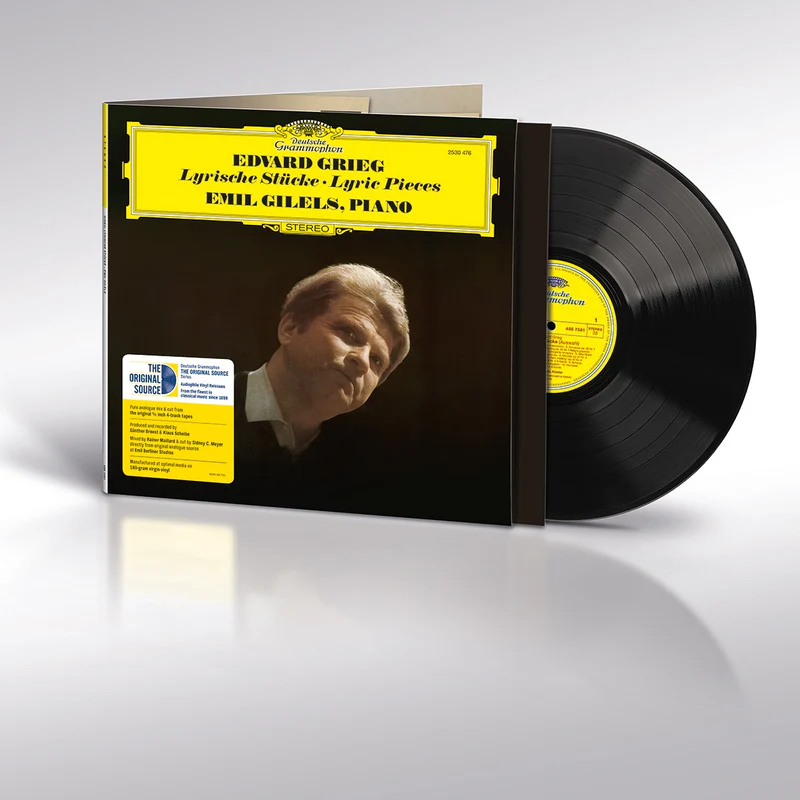

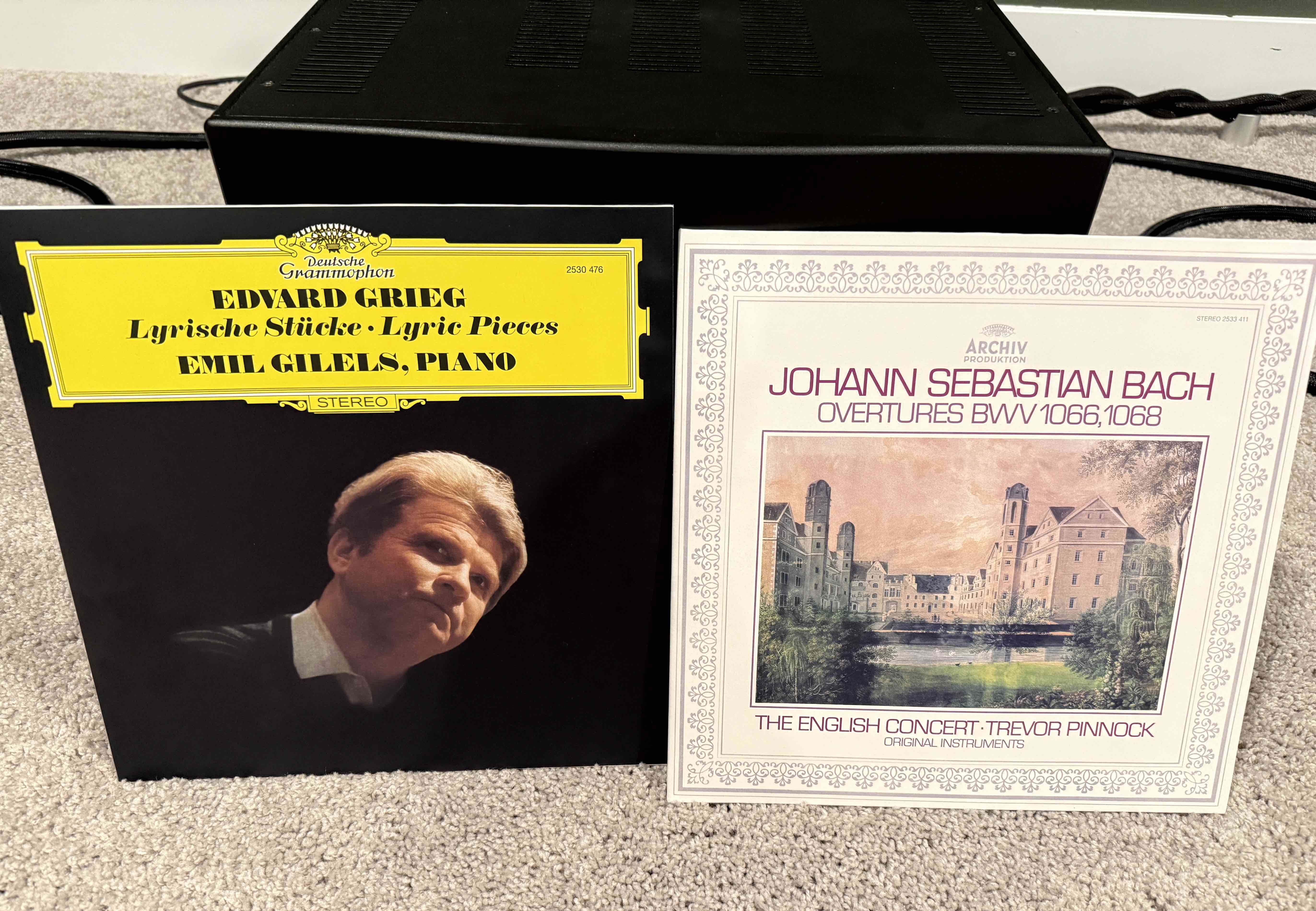

It’s been a while since I reviewed what Deutsche Grammophon and Emil Berliner were up to with their Original Source series. I’m happy to report that not only is their program still going strong, but they have also dipped into the catalog of their subsidiary Archiv Produktion, which is something I’m very excited about. This fall we saw four new releases from the acclaimed series, and before we get ready for all the titles that 2026 will bring, I thought I would recap and review these interesting release choices, starting with another title from label-favorite pianist Emil Gilels.

It's been nice to see this series tackle some further works by Edvard Grieg (1843-1907). The Norwegian composer might have recognition due to his popular Peer Gynt Suite melodies, but outside of that his compositions don’t receive much play in the 21st century, at least in North America. I’ve already reviewed one release from this series, which coupled the aforementioned ‘Peer Gynt’ with the lesser-known ‘Sigurd Jorsalfar’ incidental music. Well now we get another gem from the composer that to me exemplifies Scandinavian romanticism.

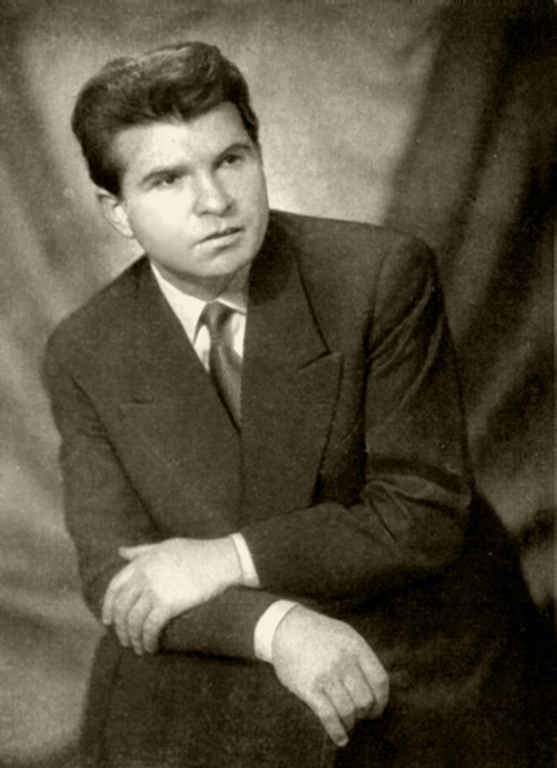

Grieg was an accomplished pianist prior to his work as a composer. Raised in a musical household, he started piano lessons with his mother Gesine before enrolling in the Leipzig Conservatory as a piano student at age 15. Even before his graduation he debuted on the stage as a concert pianist. After starting his career he began composing piano-based chamber works such as his Piano Sonata Op. 7 (1865) and Violin Sonatas No. 1 and 2 (1865 and 1867). But it was his Piano Concerto in A minor Op. 16 (1868), written when the composer was 24 years old, that launched his renown as a composer.

Edvard Grieg (1843-1907) as a young man

Edvard Grieg (1843-1907) as a young man

I’ll admit, I’d barely heard any of the Lyric Pieces by Grieg before this review. I say any of, because there’s a lot of them. Grieg published 10 volumes of solo piano works under the name ‘Lyric Pieces’ between 1867 and 1901. Those 10 volumes contain 66 short character pieces which typically last anywhere between one to five minutes in length. Recordings and performances of the complete set do exist, but they are uncommon, and it is more usual for the performer to select a program of the short pieces that suits their programmatic taste. There are a few selections that have proven memorable or popular in our musical consciousness, particularly Book 8, No. 6 the Wedding Day at Troldhaugen (1897) which is a frequently performed concert piece (pianists love it for encores) and used widely in film, television, and even video games.

For the selections here, performed by eminent Russian virtuoso Emil Gilels, the pianist has avoided the more common picks favored by performers, even forgoing the Wedding Day entirely. The peculiarity of this recording however, goes beyond programming. Recorded in June of 1974 at Berlin’s Jesus-Christus-Kirche (I would love to know the recording setup here because the sound and instrumentation is such a wild departure from orchestral recordings I have heard done in this space), this performance represents a shockingly intimate rendering from a concert pianist at the height of his fame. Gilels at this point in his career, was the definition of virtuoso, and known primarily for his large-scale performances of romantic concerti. Followers of this series might know his prowess from the previous original source reissue of his Brahms Piano Concertos which were so fiery that they actually caused issues with the cutting (read here)!

Emil Gilels (1916-1985)

Emil Gilels (1916-1985)

So then, why did a hot-blooded Russian pianist emerging onto the world stage with Beethoven, Brahms, and Liszt making up the vast chunk of his repertoire, want to record a selection of simple Norwegian character pieces often thought to be for novice pianists? Well, the works contain numerous references to Norwegian folk tunes. Gilels originally discovered these works while trying to track down a specific Norwegian folk work he heard, and discovered it in these Opuses by Grieg.

Gilels saw the musical value in these works at a time when few other pianists of his stature would take them seriously. He was initially apprehensive if anyone in the classical record-buying public would even want to hear these works. He’s reportedly quoted as remarking “No one will buy this, because no one is interested in these little pieces.” With that picture in mind, it is not only remarkable that this record was made at all, but also that it was this recording that Deutsche Grammophon chose above many others for reissue in this series.

If you are familiar with Gilels’ recordings, the playing on this LP may surprise you. Right from the get go, with the opening piece ‘Arietta’, we are introduced to a side of the pianist that is intimate, thoughtful, and artistically refined. It would be easy I think, for a pianist of Gilels’ skill and stature, to ramrod their interpretation over the music Grieg has composed here. Walter Gieseking recorded an interpretation in this spirit in years prior, and while it is a great performance, it leaves a lot of the artistic intentionality of Grieg’s score in the dust.

This performance demonstrates Gilels’ reverence for Grieg’s writing, and he plays on this recording with a transparency that makes you think you are listening to the composer himself. Gilels has two hallmark skills up his sleeve as a pianist, power and technique, but he doesn’t let either override his performance on these works, and he only shows his hand when the music calls for it, such as on the folk dance ‘Halling’ where the performer really opens up the power and sound of the instrument for the first time in the set. Otherwise he lets his sound float like petals on the wind, playing the lines with poise and delicacy.

If this set had the famous ‘Wedding Day’ number on it, it would be the only set of the Lyric Pieces you’d likely ever need, but despite that omission this represents probably one of the most refined chamber performances reissued so far in The Original Sound Source Series. The sound quality far exceeds some of the earlier piano recordings pressed in this series, and is in league with some of the best piano tone I’ve heard on record. Dynamic range is also excellent and compliments the fine range of tone color and character Gilels portrays throughout these short character pieces. It won’t shock you the way a Prokofiev cadenza might, but as far as recreating the sound of the instrument in my listening room, and more importantly, getting across the musical affects intended by the performer, this LP succeeds immaculately.

But there is one slight problem, and that is the noise floor. This album is one of delicate music, and quite frankly the pressing quality from Optimal on my promo copy was simply unacceptable for music this quiet and sublime. I’m not particularly sensitive to minor pressing noise, but the constant noise floor of this pressing was more what I would expect from my 60s Mercury LPs, not a new modern audiophile reissue. My hope is that with the continued success of the series, DG can assert some greater control over Optimal’s quality control, because the mastering and cutting here is really first rate and raises the bar on an already excellent series. If you buy this record, and I still think you should, make sure you buy from a seller that can ensure replacement copies if you get one with pressing noise like mine. If I could hear this record on quiet vinyl perhaps I would grant it a 10 in sound.

Music

Sound

Up next was possibly the most exciting release (for me) from DG in quite some time, and that is the analog revival of Archiv Produktion, the early music arm of Deutsche Grammophon started in 1948. Archiv predated the popularity of the early music movement, known in musicology circles as “Historically Informed Performance” (commonly abbreviated as HIP), releasing many works of baroque composers such as Bach, Handel, and Corelli in the 1950s and 60s, and even dipping their toes into medieval church music. This was an exciting time for musicology and these recordings represented some of the earliest widespread dissemination of many of these works and composers (Bach was ubiquitous even in the 50s, but other composers of the 16th-18th centuries were often not).

Archiv Produktion releases were also unique in their quality of packaging and documentation, as many contained extensive liner notes by musicologists that really get ‘into the weeds’ at a level not seen in many commercially released recordings up until that time. Propelling the success of Archiv were primarily Bach recordings by organist Karl Richter, who has one of the most extensive discographies of any 20th century classical musician, much of which is on the Archiv label. Richter became the organist at St. Thomas Church in Leipzig (the church where J.S. Bach had spent most of his career) at a relatively young age and eventually founded the Münchener Bach-Orchester in 1954 with which he would go on to record most of the repertoire of the German composer on Archiv. It was through these recordings that Archiv Produktion became synonymous with J.S. Bach’s music.

The St. Thomas Church in Leipzig where J.S. Bach spent much of his career.

The St. Thomas Church in Leipzig where J.S. Bach spent much of his career.

However in the middle of the 20th century, the baroque music performance grounds were rapidly shifting. Richter’s recordings, while a world away from the massive orchestral productions of Stokowski and Klemperer, were still done with modern (20th century orchestral) instruments and in ensembles that were perhaps still significantly larger than what would have been used in this music’s heyday. Starting in the late 60s, a new generation of performer/musicologist hybrid would take the stage, adopting replicas of 18th century instruments and utilizing up-to-date scholarship to better mimic what historians believe Bach, Handel, and other composer’s music would have sounded like in their lifetimes.

One musician leading the charge in this new HIP movement was Trevor Pinnock (b. 1946) who founded The English Concert in 1972 and served as its director for over 30 years. Pinnock was heavily influenced by the early experimental period instrument recordings of the 1960s by Nicholas Harnoncourt and Gustav Leonhardt (many of which done in excellent sound on the Telefunken label) and wanted to start an ensemble dedicated to period instrument performance. According to Pinnock, he felt that this was a whole new world to explore and that each performance and recording could be like a discovery.

Harpsichordist and Conductor Trevor Pinnock (b. 1946)

Harpsichordist and Conductor Trevor Pinnock (b. 1946)

I won’t write an essay about HIP (although I wrote many in college), but I will go over some of the brief characteristics that underpinned the early music movement at this time. The first one already discussed, was the revival of 18th century instruments (or rather, replicas). For woodwinds, this meant flutes, oboes, and bassoons without almost any metal keywork. The bores re-enlarged leading to a wider sound with a much softer dynamic (no need to overpower a 70 piece orchestra). For brass instruments, it meant going back to the days before the valve, and reintroducing pitched horns, often with simple finger holes. For strings, it meant gut strings, different bows, and potentially different hand positions.

The playing style altered too, as these instruments possessed a fundamentally different timbre and texture that both demanded and enabled a different technique. In the 18th century, vibrato was an effect but not a core part of the sound. Now in the 19th century vibrato use became more continuous and the instruments developed with that in mind. This is why I recommend against playing without vibrato on modern orchestral instruments even when approaching this repertoire, as it is unnatural to the core sound of the instrument. 18th century instruments however, have a much mellower, more spread sound (I’m generalizing a bit) and you can hear how this timbre wouldn’t require a core vibrato.

Scholarship grew on tempos as well, and the phrasing structure of this music began to be more understood by the performers. Long, twisting phrases are features that emerge from the music of Beethoven and Schumann, but Bach, Handel, as well as the French and Italians, thought of phrasing very differently and thus melodies and rhythms gained more brevity. The results of all this, an attempt to recreate a much older sonic aesthetic (I’ll let the musicologists fight it out on if they succeeded), yielded a sound that is much quicker, lighter, and more energetic than the musical approaches that came before.

Now there’s lots of variation of preferences, and scholarly infighting buried in that brief summary I just gave you, but if you want a very simple demonstration of how the HIP movement has shifted trends in Bach performance. Below are three different youtube recordings of Bach’s 1st Brandenburg Concerto. One recorded in 1957 by Charles Munch and the Boston Symphony Orchestra, the next by Karl Richter and the Munich Bach Orchestra done on video in 1970, and finally a modern recording from 2023 of the Netherlands Bach Society.

Hopefully through these three clips you can audibly understand the shift that was taking place throughout the 20th century in the performance of ‘early music’. This is not to say one interpretation is necessarily better than another, but rather to illustrate to a wider audience what made this particular recording by Trevor Pinnock and the English Concert so exciting and new at the time, being recorded on Archiv while many of Karl Richter’s more traditional interpretations were not only still in circulation, but still being recorded!

After all that preamble, I can finally begin to talk about the record we have here, which is Trevor Pinnock’s 1978 recording of BWV 1066 and 1068, two of Bach’s four Orchestral Suites composed between 1724 and 1731. These pieces, labeled in the program as “Overtures” are not overtures in the way we think of them colloquially (ie, a beginning introduction to an opera or ballet), but rather a reference to the French Overture style, which was a musical form widely employed in the Baroque era, often in the service of dance suites. And these suites by Bach are indeed dance suites, as each movement bears the name of a specific French dance that possesses its own unique characteristics such as the ‘Minuet’, ‘Gavotte’, ‘Sarabande’, etc.

Bach was not a frequent composer in this style, which had much heritage in French opera of the late 17th century. The style was popular even in Germany during Bach’s lifetime, but the four Orchestral Suites are the only works the composer penned in this idiom. It is somewhat strange to hear the kapellmeister’s signature contrapuntal writing in this overly dotted style more reminiscent of Rameau, but it’s in this area that Pinnock’s rendition truly excels, bringing out the dance rhythms tied to the DNA of this music. Not only is there a great sense of brisk interplay in the transparent instrumental parts, but there is also a great adherence to beat emphasis that can only come from understanding each dance form and the historical tradition it comes from.

The playing by the English Concert is uniformly fine even by today’s standards, let alone 1978 when learning a period instrument was still informalized and just a bit rock and roll. As an oboist I was most pleased to hear the playing of David Reichenberg who was one of the best recording baroque oboists around in the 1970s and 80s before his tragic passing from AIDS in 1987. The string section is likewise well positioned and imbues a great warmth and character into this performance, avoiding the sometimes cold readings that some HIP musicians were known to give, afraid to inject too much “romanticism” into Bach.

Henry Wood Hall, London

Henry Wood Hall, London

Throughout the first side of this LP, the orchestra sounded rich, natural, and excellently detailed, creating a fantastic image in front of my listening position. But the C major BWV 1066 hardly gave my Hi-Fi an athletic workout as the scale of the music is just not large in either dynamics or scope. Well, BWV 1068 on side 2 is an entirely different story. Here three trumpets and a timpani are added to the score, making the ensemble capable of both subtle air, and relative bombast which jumps out at the listener from the first timpani roll of the first movement. This suite also contains the second movement ‘Air’ that many listeners may be familiar with as the Air on the G string which is an arrangement of this work by 19th century violinist August Wilhelmj.

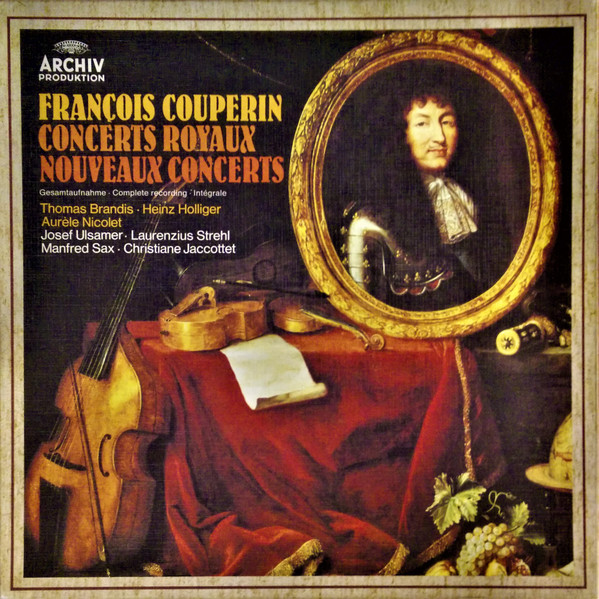

Now, as long as I’ve been collecting, I’ve always regarded LP pressings from Archiv Produktion as having superior sound to their Deutsche Grammophon counterparts. In fact before I reviewed this disc I retrieved a few of my 70s Archiv pressings and gave them a spin. While some of the trademark issues DG had in the 70s are audible, overall they can be incredibly pleasing and offer rich sonics (even if the strings sometimes do get hard). For instance I played one of my favorite Archiv releases, a 1976 box set of violinist Thomas Brandis and Oboist Heinz Holliger performing Couperin’s Concerts Royaux and Nouveaux Concerts (Archiv 2723 046, hint hint DG…). Despite a little brightness I found this to be a lovely recording of inner detail, dynamic clarity, and timbrel delicacy. I said to myself, if this new Original Source Archiv is anywhere as good as this I’ll be perfectly content.

Francois Couperin's Concerts Royaux (Archiv 2723 046)

Francois Couperin's Concerts Royaux (Archiv 2723 046)

Well, this LP blows my previous Archiv pressings out of the water. First of all, the strings have a much richer and more full bodied sound on this new release, but the dynamics are now at live concert levels or realism, this is particularly evident on BWV 1068 which is capable of thunder and lightning when called for. The rendering of Henry Wood Hall is superb, and the engineering strikes a great balance of immediacy and spaciousness. While this session was engineered by DG house engineer Karl-August Naegler, my guess is many of the artistic decisions on sound were made by Archiv producer Andreas Holschneider (who would later go on to be director of Deutsche Grammophon in 1987), and it may very well be his influence that allows these Archiv recordings to sound so uniformly good throughout the years.

Dr. Andreas Holschneider (1931-2019), music historian and producer for Archiv Produktion

Dr. Andreas Holschneider (1931-2019), music historian and producer for Archiv Produktion

I wish I had an original of this particular Pinnock recording to compare the before and after, but either way this is a disc not to be missed, if not for the excellent playing, but also for the sound that will certainly dispel the notion that baroque music is sedate or boring. My promo disc was also much quieter than the previous Grieg, although it helps that this music operates on a slightly larger scale than Gilels’ gentle piano. DG picked an excellent example of the greatness of their early music sub label for this Original Source outing, and my only hope is that they continue to dive into the treasure trove of this catalog.

Music

Sound

.png)