Re-Inventing the Classical Recital Program

Three Recent Releases Highlight Adventurous Programming and Outstanding Performances

It’s an interesting time in the classical recording industry, to say the least; some would say the industry is almost bipolar in its opposing tendencies.

On the one hand you have the traditional major labels that I and many of you grew up with - like Decca, Deutsche Grammophon, Philips (now all swallowed up by Universal Music Group), plus EMI (now part of the Warner Music empire), RCA and Sony (formerly Columbia/CBS) - putting out somewhat sporadic new releases that largely feature young, photogenic artists in more-or-less central repertoire, with occasional detours into so-called “cross-over” territory.

On the other hand you have a feisty band of smaller independent labels like BIS, Harmonia Mundi, Chandos, Pentatone, Alpha - to name but a few - plus Hyperion (now only sort-of independent since being acquired by Universal), who are all releasing a consistently excellent slate of new releases that are extremely adventurous in terms of repertoire, with an amazingly high level of consistency of performance and sonics.

Added to that you have a vast amount of new and old recordings readily available via streaming and downloads. And for the dedicated collector who still likes to buy physical product there’s a seemingly endless supply of marvelous box sets with increasingly improved remastering that will keep your bank balance humming.

While my first allegiance is always to vinyl, the fact is that classical CDs are sounding really, really good these days, and if you’ve got a decent digital playback chain (especially a player that also accommodates SACD, a format that many of the independents remain committed to by issuing dual layer discs), you are spoiled for choice amongst the new releases that continue to pour in every month.

Variety of repertoire is increasingly matched by an unorthodox approach to programming that takes us away from the standard release of complete works - ie. yet another disc of Beethoven symphonies, Chopin piano music, or Vivaldi’s Four Seasons.

There’s always been a bit of a tendency to look down on releases that contain “bleeding chunks” of different repertoire. Remember those assorted CDs from the 90s with titles like “Beethoven for Beginners”? But today many artists and labels are happy to release titles of assorted works, or even isolated sections of works, with a thematic concept driving the programming. These releases can be immensely enjoyable to listen to in one sitting: it’s like having a ready-made concert program all set to go in the comfort of your listening room.

I thought I would highlight a few of these that have given me immense pleasure since they were released within the last year or so. All feature top performers in excellent (digital) sound, and one of them is even available on vinyl. Each release takes a different approach to its eclectic programming choices.

Víkingur Ólafsson (piano): From Afar

Music by György Kurtág, Bach, Schumann, Bartók, Brahms, Birgisson, Kaldalóns, Mozart, Adès.

Recording Producer & Engineer, Editing: Christopher Tarnow

Piano Technician: Michel Brandjes

Recording: Harpa Concert House, Norōurljós Hall (Reykjavik, Iceland), April 11-15, 2022

Deutsche Grammophon

2 LP 00289 486 1682

2 CD 486 1681

Music: 10

Sound: 8

Sometimes it feels like every couple of months a stunning new performer bursts onto the classical music scene, causing critics to reach for their superlatives. With all due deference to the giants of yesteryear, the sheer range and number of outstanding young artists and ensembles who marry supreme virtuosity with superb musicianship is unparalleled right now.

Amongst an outstanding crop of young pianist virtuosos who have emerged in recent years, the Icelandic Víkingur Ólafsson has carved out a very special place. And a big part of that is due to his unorthodox approach to programming.

Until his just released recording of Bach’s Goldberg Variations, a work that is certainly not lacking in benchmark recordings (this was the work with which the young Glenn Gould asserted his pre-eminence with his “live” recording on CBS in 1956), the only release of Ólafsson’s that can claim to have been somewhat conventional was his first major-label recording for Deutsche Grammophon in 2017 of a selection of Philip Glass’s Études and other piano works - and this is hardly mainstream repertoire. It is a stunning recording, and announced the arrival of a major talent.

Since then every one of his recordings has been an event. His album of Bach transcriptions was exquisite, worthy of standing in the company of Wilhelm Kempff’s classic recordings of this repertoire for DG. Albums juxtaposing Rameau and Debussy, Mozart and his contemporaries were similarly essential purchases. He even engaged in DG’s ongoing series of remix albums that have outraged the classical purists but which have reconnected the company to its more experimental side from the 1960s and 1970s when it was happily issuing benchmark (and often the only) recordings by the enfants terribles of the European avant-garde like Karlheinz Stockhausen and Hans Werner Henze. (DG has just reissued many of these recordings in a box set - review to follow). These remix albums may be avant-garde lite, but they're still an attempt to do something a little different. If their commercial success, and the signing of artists like Max Richter and Balmorhea, means the company can record more "serious" classical fare, then why not, say I.

Then, in 2022, Ólafsson released his “post-lockdown” album, From Afar, and it immediately had more than a few critics tut-tutting their disapproval. It wasn’t the music contained therein that aroused their scepticism, although that was typically unconventional, juxtaposing a range of miniatures by Bach, Schumann, Brahms, Mozart and Bartok with music by the contemporary Hungarian composer György Kurtág. No, it was the decision to present the release on two separate discs, each containing the same program, but with one performed and recorded conventionally on a modern Steinway concert grand, and the other performed on an upright piano with felt covering the strings, and the microphones positioned within the case of the instrument; in other words, a simplified version of John Cage’s famous prepared piano. In essence, that second disc represents a non-electronic, purely acoustical, remix of the album, yielding fascinating results which, understandably, more than a few critics and listeners have dismissed as a gimmick.

I’m not so sure.

In his typically informative booklet notes, Ólafsson talks about how and why this project came about:

“As far back as I can remember, the piano was for me a favorite toy as well as an instrument for serious practice. My parents had bought the beautiful Steinway grand that sat in the living-room….. But it was often occupied - my mother taught piano at home, and my father would compose in the evenings after returning from his work as an architect.

Olafsson with his Father

Olafsson with his Father

"When we finally moved into a larger apartment and I stopped sharing a room with my two sisters, I was happy to acquire a new roommate: an old upright piano which had been in the extended family. A little worn-out and not entirely in tune, it had a most tender tone, and I soon grew very fond of the warm, dreamy sound of my bedroom piano…..

“I have experimented with recording on an upright before, but this album seemed the perfect opportunity to make two entire versions. György and (his wife) Márta Kurtág had recorded many of the four-hand Bach transcriptions and pieces from (Kurtág’s) Játékok on a felt-softened upright piano with marvelous results….

“There is a confidentiality, a whispering intimacy to the sound of the upright piano that I love to experiment with. In this recording, the microphones are so close you can hear the keys depressed and released, the pedals creak, even the pianist breathing. I want the sound to reach the listener very much as if sitting on the piano bench with me - a very different experience from sitting in a spacious concert hall listening to a shiny, black Steinway D. The upright piano calls for a different interpretation as well. Its percussive materiality and the absence of forgiving overtones demand new timings and textures, a different attention to structure. Its imperfections become acoustic opportunities. And let us not forget that it is through this medium that most students and music-lovers get to know the repertoire, and have done so for more than a hundred years.”

Listening to the upright piano version of From Afar, I kept thinking of this sentence written above: “Its imperfections become acoustic opportunities” - opportunities that Ólafsson makes full use of, and which an open-minded (and open-eared) listener can also appreciate. After making an initial adjustment, one enters the music in a completely different way. The sense of being “within” the music and “within” the instrument itself is uncanny and quite fascinating. The act of listening itself becomes a kind of psycho-acoustical journey into a virtual interior space, where resonating harmonics and mechanical sound effects created by the piano’s mechanism are as much a part of the music as the notes played. It makes you very aware of every detail of Ólafsson’s performance, both interpretively and technically - how he hits the keys, how he sustains a note and then moves on to the next one. And because this is all achieved purely acoustically, without the use of any kind of electronic processing, the experience feels very organic, even though it is still the result of a technological process, ie. recording.

Of course the music chosen by Ólafsson lends itself to being performed and recorded this way, being largely a series of miniatures defined by subtle gesture rather than barn-storming virtuosity. But do not think bringing off a program like this is any easier than tackling Liszt or Rachmaninoff: the degree of control of touch and phrasing required to execute this music as perfectly as it is done here, under microscopic scrutiny by microphones only inches away from the strings, speaks of a technical command of the instrument that is breathtaking.

Víkingur Ólafsson and Gyõrgy Kurtág

Víkingur Ólafsson and Gyõrgy Kurtág

Kurtág’s music fits beautifully into this program, often providing something of a palette-cleanser by virtue of its Satie-like minimalism. We’re a long way from the bravura of fellow Hungarian György Ligeti’s series of Etudes, which are deservedly starting to be performed and recorded more and more by a new crop of young virtuosi (I highly recommend the recent Hyperion recording by Danny Driver).

You might be surprised by how the album kicks off with Ólafsson taking a typically singular approach to a transcription of Bach’s Christe, du Lamm Gottes, in an arrangement by Kurtág himself. The sustaining pedal is used liberally to create a haze of mystery, even transcendence, over the endlessly descending figures that wrap around the melody.

Upright Piano Version

This mood continues into Schumann’s Study in Canonic Form, which you would swear was written by the old master himself.

Upright Piano Version

Listen to these two works recorded on the two different pianos and you will start to get an idea of how much music changes when the sound of it is so radically, albeit subtly, altered. Fascinating.

Grand Piano Version

Grand Piano Version

One of the great strengths of this record, and of Olaffson’s others, is how music by a familiar composer starts to sound very different when juxtaposed with the music of another from a completely different era, working in a completely different harmonic idiom. Listen to this sequence going from Kurtág to Mozart and back to Kurtág, then to Schumann. After the Kurtág, as the Mozart begins, it sounds almost radical in its traditional use of melody and simple (but never simplistic) harmony, as does the Schumann which follows another Kurtág piece. This kind of programming is so adventurous it makes us hear both familiar music with new ears, and new music with old ears, and magically the “shock of the new” also becomes the “shock of the old”. (These are all the grand piano versions).

As with quite a few DG releases nowadays, From Afar is available on both vinyl and CD. And like many such new releases, I am not sure there is any particular advantage to going the vinyl vs. the CD route - these are all mostly well engineered digital recordings. On a program like this which will easily send you into the meditation zone, I like not having to get up and flip the record. Needless to say, the upright piano version really comes into its own on headphones where the tiniest details are clearly audible. Next to Brian Eno’s Music for Airports, this is the perfect chill-out soundtrack.

Having said that I did find that the vinyl version had a tad more resolution, which really came into its own during the subtle but important acoustic cues in the upright piano recordings. Overall the sound on vinyl had a somewhat more organic quality, and I did find myself more readily listening to the whole program over again on vinyl rather than CD. That just seems to happen with records, doesn't it? My pressings (which I am guessing are from Optimal - no credit was provided on the sleeve - but Optimal seems to be DG's pressing plant of choice) were flat and quiet for the most part, but the slightest inherent pops and clicks that eluded my cleaning regime (VPI vacuum plus Disc Doctor fluids) really intruded because this is such quiet, subtle music and playing. By that same token, if the speed stability on your turntable is in any tiny way wanting, you are going to notice it because these recordings feature many long note tails from a liberal use of the sustaining pedal.

Ólaffson’s performances throughout are superb, with his formidable technique worn very lightly indeed. As with his other DG albums, his programming choices and approach to the pianos themselves reveal his strong sense of how to play to the strengths of the recording medium itself; he really understands that a successful studio recording is not the same as just plonking down a couple of microphones and playing as he would at Carnegie Hall. This is an intimate conversation, not a public speech, and invites the listener to join in as an equal partner, and to listen very closely indeed.

In every regard Ólaffson reminds us again why he is one of the most exciting young musicians on the scene today. This is a marvelous release that reveals more of its secrets with each new playing, and when you listen to the upright piano version you will have a sonic and aesthetic experience that is quite unique. If you find it’s not entirely your cup of tea, you can always go back to the more conventional grand piano version and drift away from your earthly troubles to your heart's content.

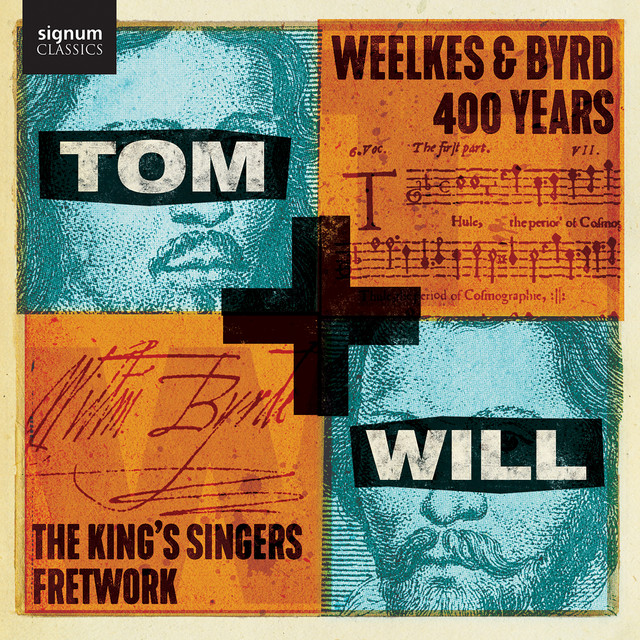

The King’s Singers and Fretwork: Tom + Will - Weelkes and Byrd: 400 Years

The King’s Singers and Fretwork: Tom + Will - Weelkes and Byrd: 400 Years

Music by Thomas Weelkes, William Byrd, James MacMillan and Roderick Williams

Producer and Editor: Nick Parker

Recording Engineer: Mike Hatch

Project Advisor and Program Notes: Dr. David Skinner

Recorded at St. Bartholomew’s Church, Orford, Suffolk, 13 - 15 January 2022.

Signum Records SIGCD 731

Music: 10

Sound: 8

On the face of it, this is a more conventional recital of vocal and instrumental English music predominantly written during the late 15th and early 16th centuries. But surprises lurk within. Two modern works by contemporary British composers commissioned specifically for this recording and combination of performers add an unexpected spice to the proceedings.

This is a lovely album, one that I have turned to repeatedly since it was released earlier this year. Hardly a month goes by when the new classical release lists do not feature outstanding recordings of music from this period, but one of the things that makes this particular release so special is the careful programming and varied sonorities derived from bringing the King’s Singers and the viol consort Fretwork together. Renaissance vocal music, while easy to listen to and disappear into even for listeners untutored in the history of this repertoire, can - over the 60 or more minutes of a CD - become a little too much of a good thing. There are a plethora of incredible vocal ensembles of different sizes specializing in this period, but in many ways the King’s Singers can claim to be the original ensemble that pioneered this music on record for the modern age.

The King’s Singers were founded in 1968 by a group of choral scholars from the Choir of King’s College, Cambridge, the most famous of England’s numerous chapel and cathedral choirs. The Choir’s annual Festival of Lessons and Carols is broadcast to millions around the world on Christmas Eve.

The Choir has the responsibility to sing at services in the King’s College Chapel every day during the academic year. Boy trebles educated at the King’s College Choir School join at an early age and give the choir its distinctive timbre derived from the unique treble sound on the soprano line, which in other choirs would be assigned to girls or women. The alto, tenor, and bass parts are performed by male students from the College.

The Choir has the responsibility to sing at services in the King’s College Chapel every day during the academic year. Boy trebles educated at the King’s College Choir School join at an early age and give the choir its distinctive timbre derived from the unique treble sound on the soprano line, which in other choirs would be assigned to girls or women. The alto, tenor, and bass parts are performed by male students from the College.

The original six-part ensemble of the King’s Singers quickly established a global reputation for excellence, bringing the art of a capella singing back into concert halls and churches, and even television - in America the group performed on The Johnny Carson Show! Their repertoire encompassed a huge range, from traditional madrigals similar to what is heard on this CD, to imaginative covers of popular songs, novelty songs, and demanding modern works often commissioned by the group. (I discussed one of their early vinyl releases here). Signing with EMI, their records were big sellers, and included early examples of cross-over success.

Today’s incarnation of the King’s Singers records with an enterprising independent label, Signum, and the repertoire released is as eclectic and immaculately performed and recorded as ever. Occasionally they have guested on others’ projects: my favorite example of this in recent years was the group’s appearance on an album titled Los Impossibles by the brilliant and equally eclectic early music instrumental ensemble, L’Arpeggiata. This track from that album is a real standout:

The CD under consideration - titled Tom + Will - marks a return to core repertoire for the group, as it also was for the choir from which the group took its name. If you sing in a chapel or cathedral choir in England, you are singing the sacred repertoire of these composers - William Byrd and Thomas Weelkes - along with that of their predecessors and successors, on almost a weekly basis. It was within these choirs that the tradition of performing Renaissance music was kept alive over centuries, for both singers and listeners, and the group has this music deeply embedded in their performing DNA, as is immediately evident on this CD.

There is an ongoing debate in the classical early music world of whether the music of the medieval, Renaissance, and baroque periods is better served by groups performing one voice to a part, or chamber choirs with several or more voices per musical line (and likewise whether boys’ or womens’ voices are preferable for the soprano and alto lines). I am not going to go into the relative merits of these arguments - frankly I think both approaches keep things interesting for performers and listeners alike. However, when you restrict the number of voices per part - as happens on this disc - you immediately gain tremendous clarity in the annunciation of the text, be it sacred or secular in nature. The words really matter in this repertoire, and the intimacy and sensitivity of the singers in projecting the texts’ meaning is apparent from the first notes.

The composers represented here - William Byrd and Thomas Weelkes - were both steeped in the English chapel choir tradition, and between the two of them they served variously as singers, organists and directors of the Chapel Royal and other such choirs.

.jpeg) William Byrd (authenticity of image not determined)

William Byrd (authenticity of image not determined)

Byrd (c.1540 - 1623), who began his career as a chorister during the waning years of King Henry VIII’s reign, managed to survive the religious wars and accompanying vicissitudes that marked this period of English history. This was all the more remarkable given that throughout his long life (83 years!) he remained true to his Catholic faith, even composing music to overtly Catholic texts, like his several Masses. (Byrd was also a master composer for keyboard, and if you want to explore his wide and varied contributions to this genre, look no further than the superb, Gramophone award-winning 1999 box set on Hyperion by Davitt Moroney, now newly available on streaming services).

Thomas Weelkes (authenticity of image not determined)

Thomas Weelkes (authenticity of image not determined)

By contrast the much younger Thomas Weelkes (1576 - 1623) was something of a rabble-rouser. In the excellent booklet notes by David Skinner that accompany this release, entertaining reference is made to his repeated drunken sorties and propensity for foul language that got him into regular trouble with Church authorities. But something of his rebellious temperament found its way into his music, which is acknowledged to be some of the boldest and most forward-thinking of its period.

What we have on this CD is both unaccompanied and accompanied vocal music by both composers, and several purely instrumental works performed by the outstanding viol consort, Fretwork.

Now I can hear some of you wondering, “What is a viol consort?” Well, viols are string instruments which were the precursors to the familiar violin family (although both families of instruments co-existed for a period of time until the violin family came to dominate during the later Baroque and Classical periods, by virtue of the instruments' greater projecting power). Unlike violins, violas, ‘cellos and double basses, viols have six strings and are bowed under-armed (as opposed to over-armed). Gut strings tied across the fingerboard are used less as a guide for tuning, more to enable the player to press the string against these “frets” and maintain an open-string sonority on any played note. Vibrato is generally kept to a minimum, used more as an ornament for emphasis and variety rather than as a steady tonal device.

A Viol Consort

A Viol Consort

In their heyday, the different sized instruments, ranging from treble and tenor to bass and larger violone, would play together in what were called consorts (viols only) or broken consorts (with other instruments included, like recorders). Viols are all held on the knees like a ‘cello, but without the additional support of a spike going into the floor. This is why the instruments’ full name was actually viola da gamba, or gamba for short. The bass instrument developed as a solo instrument in its own right. Bach wrote sonatas for it, and several French baroque composers turned it into a virtuoso solo instrument, in particular Marin Marais. One of the most famous works written for the bass viola da gamba is Marais’ musical account of having a bladder stone removed!

English composers came to write extensively for viol consort: the instrument’s plaintive, almost muted quality, that could communicate a certain restrained passion, was a perfect vehicle for that characteristic English melancholy and emotional deference which has informed much of English music across centuries and genres. The various 3, 4, and 5-part instrumental works, like the Fantasias and In Nomines for viols by composers like John Jenkins and Henry Purcell, lacked nothing in terms of compositional and expressive sophistication, and can be heard as the precursor to the string quartet.

The other thing about viol consorts is that their sound blends perfectly with voices, and the composers on this album exploit that blend to great advantage to reinforce the music’s deep wells of emotion that are veiled by the propriety of the period’s tonal and rhythmic idioms.

That sense of contained emotion, of fervent prayer emerging from the shadows of the cloister, is evident on the very first track of this CD: William Byrd’s Praise our Lord, all ye gentiles, with the viol sonorities subtly reinforcing the plaintive edge in the music.

Then we get a delicious contrast when Byrd’s delightful madrigal If women could be fair is accompanied by plucked viols, sounding for all the world like the largest lute that ever was.

What you will immediately notice in this music is how important subtle shifts of harmony and rhythm, articulation and legato are to the music’s impact. The challenge (and fun) of singing or playing this kind of music (both of which I have done) is the subtlety with which you have to use the limited means at your disposal. This is not music of big affect: it is all about accuracy of intonation, precise phrasing, and the deft use of varied articulation and dynamic contrast (and occasional ornamentation) to create variety. Listen to the first purely instrumental piece, Weelkes’s Pavan No. 3, and you will hear his brilliant use of carefully applied discord, plus call and answer phrases, to propel the music forward.

For some 40 years, Fretwork has been the pre-eminent viol consort, appearing on a myriad of essential recordings of this repertoire. Prior to them, viol consorts like the Ulsamer Collegium (which recorded for DG’s early music imprint, Archiv) tended to try and make viols sound as much like violins and ‘cellos as possible, using more or less continuous vibrato which killed the subtlety of the music and betrayed the instrument’s intrinsic character. Fretwork changed all that, and their recordings remain exemplars of all that's best about the historically informed performance movement. Listening to this disc will demonstrate why.

The King's Singers and Fretwork

The King's Singers and Fretwork

Just when you think you know where this disc is going, we get to hear the ravishing setting of Ye Sacred Muses by the contemporary Scottish composer James MacMillan. Following on the heels of Byrd’s own moving lament upon the death of his great forbear, Thomas Tallis, MacMillan channels Byrd’s idiom and makes it completely his own. MacMillan is without question one of the most distinctive composers working today, unashamedly embracing his Catholic faith in music that is both unfailingly modern and also rooted in the past. His work reminds me a great deal of Benjamin Britten, another composer whose music always communicated so directly with his listeners, and who was a master at communicating the multiple layers of meaning in the words he set. If you like this exquisite setting (which MacMillan turns into an Ode to William Byrd), then I urge you to explore his work further.

The curtain-raiser to the other new work on this disc is Weelkes’s setting of Death have deprived me, a superb example of this composer’s art, where wandering harmonies and isolated phrases sometimes just peter out - a musical cessation of life - before the ensemble joins together in a forceful acknowledgment of the inexorability of death.

It leads into the viols’ introduction to Roderick Williams strident setting of John Donne’s sonnet shaking his fist at Death, culminating in his cry of “Death, thou shalt not die”. While there are wonderful moments here, I found myself yearning for something that did not feel so obvious in its musical gestures, something that was less a moment-to-moment word setting. Britten, for example, would have found a way to incorporate the individual word painting within a larger design (for a comparison listen to Britten’s setting of John Keats’s To Sleep, in the Serenade for Tenor, Horn and Strings).

Having said that, I love the viol writing in this piece, especially at the opening. The last section - where the music settles down into a less rhetorical idiom - is very moving, as Death is both defied and accepted

.The instrumental strains of an In Nomine by Weelkes are the perfect transition into the final group of vocal pieces, all by William Byrd. This culminates in two intensely moving settings. The first is a reflection by an old man upon the course of his life, asking God to forgive “the follies of my youth.” The music and the sentiment feel intensely personal.

Finally, in a most moving conclusion, Byrd offers up a musical prayer to Queen Elizabeth I, wishing her “a long life, even for ever and ever. Amen.” The poignancy of a staunchly Catholic composer wishing for the good health of the Protestant monarch who - for the moment - assured the subjugation of his religion in his homeland is unmistakeable. Byrd’s setting is typically deceptive in its apparent simplicity - a largely chordal treatment of the text, but with moments of delicious dissonance, and a melancholic tinge throughout.

To perform this kind of music as well as the King’s Singers do is no easy task, but throughout this glorious disc they hide their virtuosity behind what sounds like the most relaxed singing in the world. This is a disc I will return to often, for it reveals its many layers only with repeated listening. The sound, courtesy of the ever reliable Mike Hatch, is - like the performances - intimate and unassuming. It takes you right into the heart of the music, hiding its sophistication behind a veil of apparent simplicity. Just like the music does.

![]() Kuss Quartet: Krise Crisis

Kuss Quartet: Krise Crisis

Music by Haydn, Ciurlo, Schubert, Bartók, Shostakovich, Bertelsmeier, Reich, Soghomanian (Komitas), Mendelssohn, Smetana, Janáček, Escudero.

Recording Producer: Dirk Fischer

Balance Engineer: Bastian Schick

Editing and Mixdown: Dirk Fischer

Recording: Kornspeicher, Dorfmühler, Lehrberg, Germany 6 - 9 December, 2021.

Rubicon CD RCD 1102

Music: 10

Sound: 8

Last, but by no means least, is a highly unusual disc of music for string quartet, performed by the Kuss Quartet - an ensemble which was new to me, but which I will definitely be following closely in years to come.

The Kuss Quartet performing Beethoveniana

The Kuss Quartet performing Beethoveniana

Krise Crisis is essentially a concept album, bringing together a wide range of movements from different quartets alongside new commissions to explore the many different forms of crisis we are facing in today’s world. The immediate catalyst was the quartet members’ experience of the pandemic and its aftermath - an event which heightened a sense of crisis in the world. As violinist Oliver Wille writes in, again, excellent booklet notes:

“…. Occupying us was the issue of how we might best express ourselves as artists in a time of huge uncertainty as well as so many cultural and political problems….

“It’s remarkable, the creative power that can at times be unleashed from personal, political and topical pressures. This also holds for compositions for string quartet, if you trawl through our rich repertoire with this in mind, bringing confirmation that art is and always has been something indispensable for humankind….

“…. Our impromptu concept duly grew into a selection of pieces for this present moment in time, organized dramaturgically - or rather, presented in a sequence where the listening experience was a key determining factor. What we ended up with was three thematic strands, each of which we complemented with a contemporary piece of music…”

Sound like a downer? Absolutely not. This is program building and playing of high imagination and scorching immediacy, and despite (or maybe because of) the intensity of the music and performances, the listener cannot help but emerge reinvigorated. This is not a disc I put on often (like many of David Bowie’s or Miles Davis’s records), but when I do I feel like I have listened to something very special indeed, that demands my full, active engagement, and that is quite unique.

There was a time, not so long ago, when a classical ensemble wouldn’t have dared to put out a disc like this, reducing masterworks of the string quartet repertoire to a series of so-called bleeding chunks. But, with everyone in the classical marketplace competing for the attention of a diminishing audience willing to shell out good money for physical product, finding a unique hook for your product can help you stand apart, both as artists and as a label. A challenge is also an opportunity, and here these young performers have found a very creative way to set themselves apart, and make a strong musical (and, by implication, political) statement in the process.

Of course none of this would have worked if the performances weren’t top notch. In some ways they have to be even better than the considerable competition in this repertoire, otherwise why would anyone listen to a series of extracts rather than complete works. Rest assured, the performances here are all of benchmark quality, with pinpoint accuracy of intonation, startling dynamics, unanimity of expressive purpose, and a vivid, arresting sound that is never strident, even in the music’s most strident moments. This is a very exciting ensemble to listen to, and I can offer no higher praise than to say that after listening to this disc all I wanted was to hear the Kuss Quartet set down complete performances of all the string quartets whose separate movements are contained therein. (Actually, there is one complete work on this disc, Janacek’s landmark “Kreutzer” Quartet, and the performance is fully the equal of any other I’ve heard).

Right upfront the Kuss Quartet curry my favour by opening with the string quartet version of Haydn’s Seven Last Words of Our Saviour on the Cross. This is an extraordinary work, completely sui generis, and it is neither often performed nor recorded. Its austerity can make it a little hard to take as a complete performance in one sitting, but opening this Crisis program with its opening movement is a masterstroke. The music sets up an immediate tone of arresting urgency. “Sit down and listen!” it seems to say. “What I have to communicate - right here, right now - is important.”

And listen you do.

But where the album goes next is as unexpected as it is brilliant.

Sparse, naked chords built out of string harmonics usher in the baleful, musical wasteland of the first modern work on the disc: Francesco Ciurlo’s Hasta pulverizarse los ajos. The composer writes:

“The title is taken from a poem by Alexandra Pizarnik in which she defines rebellion as ‘mirar una rosa hasta pulverizarse los ojos’ (‘looking at a rose until your eyeballs implode’). My metaphorical response both to crisis and the inherent haziness of my material was to deploy it in a simple and diatonic way and to obsessively try to pin it down throughout the entire duration of the piece until ‘your ears implode’.”

There follows another movement from Haydn’s masterpiece, and then the Scherzo movement from Schubert’s Death and The Maiden quartet, written at a time when the composer was seriously ill and realized he was dying - in other words the work is an expression of personal crisis in the face of impending death.

The next sequence is devoted to works in which composers deal with political crisis in their music. Bartok composed his 6th Quartet as a response to the outbreak of World War II, and the movement played here expresses his anguish.

Shostakovich’s 8th Quartet is, like most of his music, grappling with the role of an artist - and how to find a way to express himself truthfully - within the confines of a totalitarian system that polices even aesthetic choices.

The new work which follows, Birke Bertelsmeier’s Krise, sounds like it could have sprung directly from the sound world of Bartok and Shostakovich. Writes the composer:

“Crisis in the sense of an intensification and progressive narrowing of awareness, where even positive and happy moments are reconfigured within the swirling vortex and need, at best, to be undergone as rapidly as possible.”

This transitions into the last section of Steve Reich’s response to 9/11, WTC 9/11 for string quartet and pre-recorded tape. “The world to come… I don’t really know what that means….” declares one of the voices. Reich’s haunting musical vision remains one of the most powerful of all the artistic responses we’ve had to that fateful day, and even just this short extract makes a very strong impression here. Presciently, Reich has stated that his work’s title refers more to “the world to come” than to the site of the terrorist attack.

There follows another response to political terror, Komitas Vardepet’s Spring, a haunting, elegiac setting of an Armenian folk melody that has become associated with the horrors of mass murder.

Uneasy consolation arrives in the form of the Adagio from Mendelssohn’s 6th Quartet, his response to the death of his beloved sister Fanny, whom he was to follow only a few short months later. Mendelssohn’s String Quartets are one of the most unfathomably under-appreciated corners of this repertoire, and it is wonderful to hear this music performed as persuasively as it is here.

Smetana’s autobiographical first quartet From My Life depicts another personal crisis, the sudden onset of tinnitus that led to the composer’s deafness. Music of joy and exaltation suddenly gives way to a musical depiction of this catastrophe, with the violin mimicking that high ringing tone we associate with tinnitus. The movement ends with a wistful look back to happier times.

Janáček’s semi-autobiographical first quartet is one of the more intense musical depictions of personal crisis, modeled on Tolstoy’s novel “The Kreutzer Sonata”. The work explores all the intense feelings that can arise from obsessive love - desire, obsession, jealousy, even murder. Janáček wrote the piece when he was in thrall to an unrequited love for a much younger woman whom he’d met while on vacation with his wife. His correspondence with the woman also inspired his second quartet, subtitled “Intimate Letters”. He once wrote to her: “You are there in my compositions, wherever there is pure emotion, sincerity, truth, ardent love…”

This is a work whose intensity of expression can sometimes make performances come across too stridently, with the playing devolving into sound that can be hard to listen to. I think this performance finds the perfect balance between conveying the work’s emotional turbulence and maintaining a necessary level of tonal and timbral equanimity.

The final new work which concludes the program is Post by Oscar Escudero, which the composer describes as “a social experience for string quartet, electronics and audience”. I can imagine some listeners will find this a little jarring after all that has gone before. But as a work in itself, I find it thoroughly engaging. I will confess that I still haven’t quite figured it out (!), but does that really matter? I’ve always been a fan of music that combines electronic tape and live performances, and I find the interaction here most effective. But is this truly a work of “Crisis”? Maybe, in the sense of its post-modern exploration of the creative process…..

On one listen to this disc I forgot I had hit the “repeat” button, so after Post the CD went back to the beginning and the opening of Haydn’s Seven Last Words. This actually worked brilliantly, with the Haydn seeming to answer the questioning that drives Post. As in all things, context is everything.

And context is really what drives the value of all the releases I’ve reviewed here: familiar and unfamiliar music and sounds gaining new meaning by being placed in new contexts. The results in every case are refreshing and stimulating, leading the listener into new appreciations and considerations. To ears that can become jaded through over familiarity with much of this music, that is no small achievement. It is a great argument for engaging in the kind of carefully considered and imaginative new approaches to programming in classical music exemplified by each of these outstanding releases.

.png)