Remembering Carl Davis (1936 - 2023): The Man Who Gave Silent Films Their Musical Voice

A Personal Reminiscence of One of the Most Important Film and TV Composers of the Last 60 Years—Beatles fans may already know of Carl’s collaboration with Paul McCartney on The Liverpool Oratorio

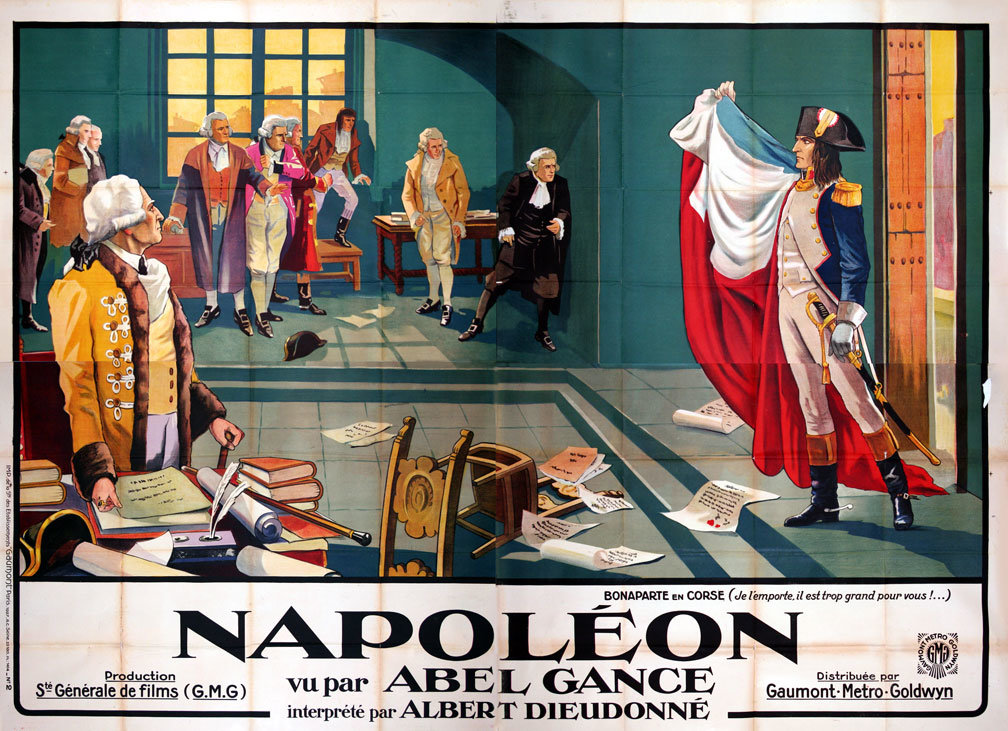

On a cloudy English November weekend back in 1980, my best friend and I decided to quit the dreaming spires of Oxford and head to London for a screening of a then almost unknown French silent film, Napoleon, made by Abel Gance, a name known primarily to movie buffs, and really only silent film movie buffs at that. A film that lasted over 6 hours.

An original poster for Napoleon. One of these massive posters hangs in the lobby of the Mary Pickford Theater at the Academy in Los Angeles

An original poster for Napoleon. One of these massive posters hangs in the lobby of the Mary Pickford Theater at the Academy in Los Angeles

Little did we know we were about to encounter not only one of the supreme masterpieces of cinema, but also experience an accompanying music score, performed live with a symphony orchestra, that was unprecedented in its scale and impact. As the screening played out over an afternoon and evening, the audience (full of the crème de la crème of the British arts scene) could hardly believe what they were experiencing. The sheer filmic force of Abel Gance’s vision, incorporating film techniques that were still experimental some 55 years after the film was made, was matched and amplified by a score that mirrored every twist and turn of the narrative, culminating in an explosion of grandeur as the film shifted into a triptych of three adjacent screens (Gance anticipated the creation of Cinerama by nearly 40 years). The seats shook from people crying, overwhelmed by emotion. That screening remains one of the most memorable artistic experiences of my life.

Albert Dieudonné as Napoleon

Albert Dieudonné as Napoleon

From the Battle of Toulon sequence, tinted red as was the custom in the silent days

From the Battle of Toulon sequence, tinted red as was the custom in the silent days

It was also my first conscious introduction to the music of Carl Davis - I say “conscious” because, without knowing it, I was already familiar with his music via a slew of memorable TV scores for popular British shows. I just didn't know he was the person who had composed them.

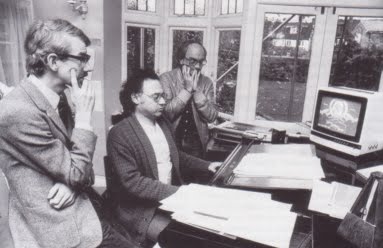

After that screening of Napoleon, Carl, working in tandem with his co-conspirators Kevin Brownlow (the world’s foremost expert on silent film), and producer David Gill (the person who made it all happen practically and commercially), would go on to become the trailblazer for a worldwide revival of silent film music, both vintage and new (usually performed live to picture with an orchestra). The team brought the long-neglected medium of silent film back into film theatres and festivals, playing to sell-out crowds, in a manner hardly foreseen back in 1980 when that Napoleon screening took place.

(from left to right) Kevin Brownlow, Carl Davis and David Gill

(from left to right) Kevin Brownlow, Carl Davis and David Gill

It was also the beginning of my own considerable interest in, and love of, Carl’s music, both as an audience member and as a journalist, and I would come to write quite a bit about his adventures in film music - especially the silent scores - over the next 40-plus years. At one point he even hired me to write various publicity and other material for his PR portfolio! I interviewed him and his colleagues extensively over the years for various articles.

Funnily enough, when news broke of Carl’s sudden death this week from a brain haemorrhage at the age of 86, the first thing that crossed my mind was not any of the wonderful scores and performances I had heard him conduct, but rather a lunch in Boston with him and his long-time manager some time in the late 80s. Carl, a raconteur of the first order, was on particularly good form that day, and I have rarely had such an entertaining meal, full of stories, music and film industry gossip, plus some serious music talk. You always had a good time hanging out with Carl, a fact confirmed in the announcement of his death in The Guardian:

Sam Wigglesworth, director of performance music at Faber, Davis’s publisher since 1990, said:

“To spend time with Carl was an energising – often dizzying – joy … Few, if any, composers today can boast such an eclectic life in music, and our world will be a duller place without him.”

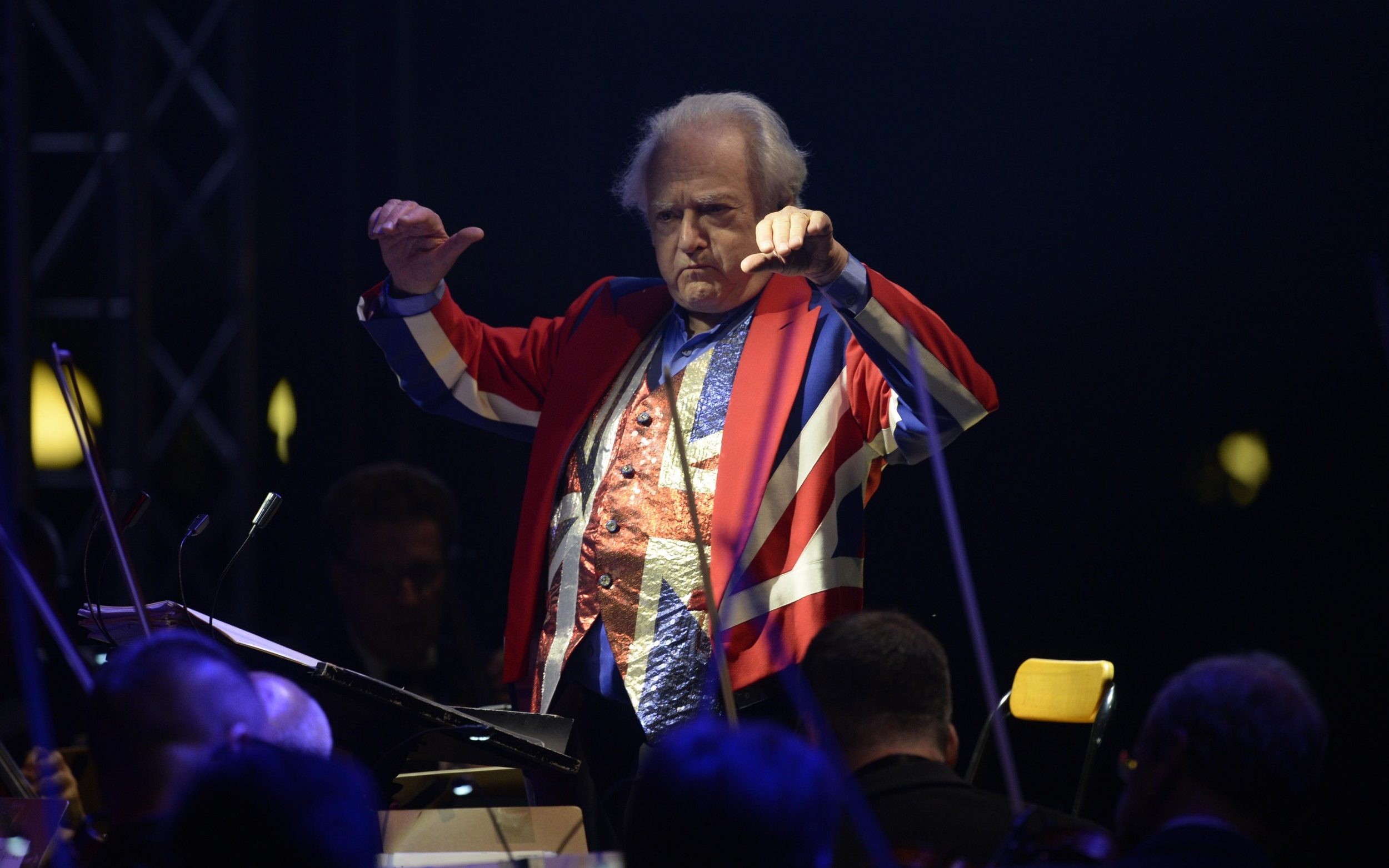

Let me say one other thing about Carl right upfront: the man had style! With his craggy features and a mane of fabulous hair he grew long for much of his life, supplemented by the distinctive, colorful and zippy jackets that became his trademark on the podium, he was the very picture of “THE CONDUCTOR”!

That American pizzazz was so refreshing in Britain’s somewhat staid classical and studio world. If Damon Runyon had wanted to write a character who was a classical musician into one of his stories of New York’s eccentric denizens, Carl would have fit the bill perfectly. Add to that his devilish sense of humor, a no-nonsense approach to music-making, a considerable intellect which he wore lightly, and an encyclopedic musical knowledge and literacy (he could compose in any style) and you have one hell of a force of musical nature - which is exactly what Carl was. His workload was punishing: composing early every morning for several hours, then touring or rehearsing or recording, then performing in the evening. Next day repeat. The man was a music machine.

Born in Brooklyn in 1936, Carl adopted England as his native land in 1960, and quickly established a formidable presence on the music scene, especially in TV and film music. One of his greatest early successes was writing the music for the landmark ITV documentary series, The World at War (1973-4), whose main theme gained tremendous popularity in its own right, and is today considered one of the greatest main themes for a TV show ever written (alas I could not find a version with the main titles).

I remember asking Carl one time about settling in the UK. He talked about how at that time British television, film and theater (he composed for both the National Theater and Royal Shakespeare Company) were doing such quality material that there were far many more interesting musical opportunities for a composer in the UK than in America, and steady work meant steady pay. As far as I could tell he never had any of the hang-ups many other composers had about working in film and TV; many felt they were sacrificing their serious art on the altar of commercialism and popular entertainment. Carl had no such qualms: he knew that TV and film afforded him the opportunity to compose in the widest range of styles and genres, and to be paid well in the process (unlike most "serious" composers). He took film and TV seriously, and it showed in the quality of the music he wrote for them.

You also have to remember that this was a time when classical music was going through the paroxysms and convulsions of finding a way forward after the supposed death of traditional tonality. If you were a serious composer you were expected to fully embrace atonality, serialism or, better still, all of the above as embodied in the manifesto of the Darmstadt school (Stockhausen, Boulez et al). If you remained working in a tonal idiom, like Britten or Shostakovich, you were considered - especially in academia - as simply the last gasp of a dying art-form (how things have changed). If you were a commercial composer who actually wanted to make a living writing music people actually wanted to listen to, like a Carl Davis, then you were beyond being taken seriously at all. No skin off Carl’s nose. And incidentally he was quite happy to adopt some of the more radical modernist classical techniques when a film called for it, as in his scores for Erich von Stroheim’s existential cri de coeur, Greed (1924), and the Lillian Gish psycho-drama, the expressionistic The Wind (1928). (Tellingly, and smartly, Carl hired the brothers David and Colin Matthews, both modernist classical composers, to work as orchestrators on those scores).

Composing for Silent Films

In the late 1970s, film historian, editor and director Kevin Brownlow’s classic book on the early days of Hollywood, The Parade’s Gone By, inspired Jeremy Isaacs, then Director of Programs at Thames, to give the go-ahead for a series about the American pioneers of film.

The aim of this series was twofold: to give a history of the early film industry, told largely in interviews with veterans of the period, and to present the actual footage of the time, be it clips, outtakes or newsreel, in as authentic and pristine a manner as was possible.

This involved finding the best possible prints (not always an easy task), projecting them at the correct speed (thus eliminating the traditional “speeded-up” image of silent film), and providing music which would genuinely enhance the visuals. Recognizing Kevin Brownlow’s dedication to the original quality of these old films, series co-producer David Gill nevertheless had misgivings about how a modern audience would react to them: “I still had a slight reservation because I had been away from silent films for so long. We not only had to demonstrate these films existed and make an interesting, educational program, we had to build an audience, capture their imaginations, make it an entertainment – something they could surrender to. And the only way I could see that happening was not just by using music, but by really spending so much money on the music -- composing it and being able to afford a large orchestra, something which documentaries never envisage. Then, as soon as we started seeing the results during the course of production, we were astounded by the effect it had on the film. A whole new entity appeared, and we could see it from the reaction of all the people who saw the programs.”

Carl had already worked with David Gill on The World at War, and jumped at the chance to score Hollywood. “First of all I did quite a bit of research on how the film scores were created in the period. The series really ran the range of all the styles of film of the period, and involved me in thinking and creating for a great many clips.”

Carl resorted to many of the methods of the silent era: borrowing chunks of the classics, cobbling together popular pieces of the time; anything that would go with the film. Throughout he would interweave his own music, often finding inspiration in certain composers to reflect this style and mood of a film or actor in the accompanying music: Rimsky-Korsakov for Douglas Fairbanks and The Thief of Baghdad, Liszt for the soul of Greta Garbo in A Woman of Affairs.

The Hollywood series was a surprise hit, and in succeeding years Carl collaborated with Gill and Brownlow on many more fine documentary series about silent film, including the fascinating Unknown Chaplin. Chaplin filmed all the rehearsals for his films, and kept the footage, so you can literally see the director’s creative process unfold before your very eyes. Of course, Chaplin also wrote music for many of his films, and Carl was a huge admirer of his musical gifts, and conducted restorations of the full scores on many an occasion.

Back to 1980 and Napoleon. Not surprisingly, with the success of Hollywood, Carl was itching to try his hand at a full-length score for full orchestra to accompany a theatrical presentation of a silent film. The opportunity to do so did not arise until the BFI earmarked Kevin Brownlow’s reconstruction of Abel Gance’s epic Napoleon for the London Film Festival in 1980. This film, forgotten and lost for decades, had been painstakingly restored by Kevin Brownlow over many years from fragments found all over the world. The film is a cornucopia of experimental film techniques, including a final 20-minute section in which three cameras/projectors were used to create vast panoramas and split screens as Napoleon prepares his newly reinvigorated army for the invasion of Italy, and dreams of future victories and his beloved Josephine.

With the theatrical screenings of Napoleon set to premiere at the London Film Festival, in three months Carl had to produce over five hours of music. As much out of practical as aesthetic considerations he quickly settled upon the idea of using the music of Beethoven and his contemporaries as the backbone for the score, an apt choice in view of the youthful Beethoven’s admiration for the young Napoleon. “One of the first things I learned about silent film musicians of the time, when I was working on the Hollywood series, was that they had absolutely no inhibitions about robbing, like grave robbing, and using classical compositions to support the score.”

Sometimes an important film would be distributed with a specially composed score. Whenever possible Carl made reference to these, and often found useful source material (various army and popular songs of World War I for The Big Parade, for example). On several occasions he reconstructed an entire original score – like for D.W. Griffith’s Broken Blossoms.

But in the case of Napoleon in 1980, Honegger’s original score had yet to be rediscovered, so Carl found himself plundering the musical treasure house of the Classical period. (As the score expanded in later years with more newly found footage added to the print, Carl integrated some of Honegger's original score into his own).

Yet he was careful never to use music which might jar with the film’s carefully constructed historical authenticity. “I had a notion, which I always follow, which is to try and be faithful to the period, or at least to pay service to the period it was done in. I would use Beethoven, but only up to compositions of about 1810, and I would not go into Berlioz, for instance, or Schumann or Wagner or any of those pieces which might be appropriate from a mood point of view, but which I felt would betray the spirit all of those wigs, corsets and breeches, so to speak.”

Amongst Carl’s most memorable original themes for Napoleon was "The Eagle of Destiny”, which accompanied the appearance of an eagle at several key moments in the life of the future Emperor.

Young Napoleon and the Eagle of Destiny

Young Napoleon and the Eagle of Destiny

The eagle's final appearance at the climax of the film, spread across the vast triptych of screens, is guaranteed to bring an audience to tears.

Carl continued to compose and conduct his silent film scores for the next forty years, inspiring new generations of composers to do the same all over the world. For years the London Film Festival would premiere Carl’s new scores with a theatrical presentation of a beautifully restored print. To experience any of these glorious films with a sell-out crowd was to understand fully the unique and visceral experience of watching a silent film with an orchestra playing a first-rate score specially composed for the occasion.

Here in Los Angeles, Carl appeared at the 2014 Turner Classic Movie Festival conducting his new score for Harold Lloyd's Why Worry. Suzanne Lloyd, Harold's granddaughter, was a big admirer of Carl's work. Carl was especially adroit at scoring comedies - not an easy feat. He always found the perfect balance between matching comedic action and playing the laughs (ie. mickeymousing as it was often called), and keeping the emotion true, the story on track. His scores for the Lloyd films, including Safety Last, and Buster Keaton's The General and Our Hospitality, are amongst his very best.

In this short promotional video for the Pordenone Silent Film Festival, Carl talks about his score for King Vidor's The Crowd, a masterpiece that is one of my personal favorites. Its tale of a loving "everyman" couple buffeted by life's joys and sorrows is as relevant and powerful today as the time when it was made. The video includes extracts from the film, and Carl conducting rehearsals and the performance.

Here is the opening of The Crowd:

Flesh and the Devil (1926) charted the course of a doomed love affair between the characters played by Greta Garbo and John Gilbert, which turned into a real-life romance. Their first day of shooting together was the scene where the characters meet on the platform of a train station, and you can see the two actors fall in love for real on camera.

Carl modeled his score on the music of the late-Romantic composer Richard Strauss, and in the scene where the characters meet at a ball and share their first kiss, his music exquisitely captures the first flowering of erotic passion. Note how in the dialogue before the kiss the score creates a "dialogue in music", with different instruments "talking" to each other until passion overwhelms. The craft and art being brought to bear here is of the first order, working in complete harmony with the actors, direction (by Clarence Brown), and lighting (by cameraman William Daniels).

In the mid-80s I was sent by the Financial Times to cover a week of these films - now named the Thames Silents - being presented at Radio City Music Hall in New York, an unbelievable thrill. I got to meet Lillian Gish, then in her 90s, who, although becoming frail, was still as sharp and witty as ever, and Lauren Bacall, who fully conformed to her sultry on-screen image. But maybe the best part was just occasionally hanging out with Carl, Kevin, and David Gill, who between them were a fountain of knowledge about film. I had spent time with them in the early days of the Thames Silents at recording sessions at the legendary Olympic Studios in Barnes, London, and watching Carl at work was reminiscent of watching Elmer Bernstein conduct his score for An American Werewolf in London in the same studios. These were old world film composers of the first order, masters of the considerable technical and aesthetic demands of writing for film, able to work fast with minimum fuss (and minimum technological assistance). They also wrote real music with real melodies, not notated drum circles and chords and drones set to "repeat" which dominate much of today's film music. They are a dying breed.

The last time I heard Carl conduct Napoleon was in 2012 at a sell-out series of screenings at the gorgeous art deco theater in Oakland, the Paramount, under the aegis of the San Francisco Silent Film Festival.

For reasons far too complicated to go into here, the Brownlow/Davis version of Napoleon had never before been screened in the U.S., so people came from all over the country and the world to attend the event spread over two weekends of screenings. Again I covered it for the Financial Times - you can read my review here. It was the most spectacular presentation of the film I ever attended, with the final triptych spread across a screen over 100 ft wide. You had to marvel at Carl’s fortitude and stamina, conducting this epic, nearly 7-hour score, in sync to picture with no technological aids, in his mid-70s.

Napoleon at the Paramount, Oakland, 2012 (photo by Pamela Gentile)

Napoleon at the Paramount, Oakland, 2012 (photo by Pamela Gentile)

Beyond the Silents

Along with his unique silent film scores, preserved on various blu-rays, DVDs and laserdiscs, Carl always had a thriving career as a film and TV composer. Probably his best-known film score is for Karel Reisz’s The French Lieutenant’s Woman (1981), which won him a BAFTA award, and featured an Oscar-winning performance by Meryl Streep, and an Oscar-winning script by Harold Pinter. His TV scores remain engagingly popular, especially his catchy music for the BBC’s blockbuster adaptation of Pride and Prejudice (1995). Once more Carl drew on his extensive knowledge of music from the Classical period, and had a featured solo fortepiano part played by Melvyn Tan, one of the pioneering soloists on that precursor to the modern piano. His score burbles along to the comedy of manners with perfect timing, and when love is in the air (or rather - this being Jane Austen - frustrated and unspoken love), his music will pull on your heartstrings with just the right amount of sentiment.

Beyond screens small and silver, Carl has written much fine concert music. He was a lifelong lover of the ballet, and composed a series of notable ballet scores for major companies, including Alice in Wonderland and Aladdin: a perfect match for his abilities. They are lovely works. As with the silent film scores, his ballet music tells the story with memorable melody and colorful orchestration to spare.

A later project that he felt passionately about was The Last Train to Tomorrow, which commemorated the famous Kindertransport rescue of children from Nazi-controlled Europe. Written for children’s choir, actors and orchestra, the work was premiered in 2012 by Britain’s great Manchester-based orchestra, the Hallé. Clearly indebted to the example of Britten’s works for children, this is a moving work which deserves to be more widely known and performed.

Beatles fans may already know of Carl’s collaboration with Paul McCartney on The Liverpool Oratorio, celebrating the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic’s 150th anniversary. Carl loved the Beatles, and had already done a fun CD of Beatles covers with the celebrated a cappella vocal ensemble I recently wrote about, the King’s Singers. Carl remarked to me once on how extraordinary McCartney’s gift for melody was. McCartney (who does not read music) would come into Carl’s music studio and start humming tunes, and the work grew from that.

I will end by remembering a thrilling evening in 2011 of James Bond music Carl conducted down in Orange County in the splendid new Renée and Henry Segerstrom Concert Hall. I took along my then 14-year old daughter. One of the featured singers was Mary Carewe, who back in my post-University days in London had most graciously recorded demos of my pop songs (and made them sound much better than they were). Mary, then and now, could basically sing anything, in any style, in more or less any range, and has been one of the go-to singers on the London session scene since she was a youngster. So she was more than fully up to the challenge of following in the footsteps of Shirley Bassey, Carly Simon, Nancy Sinatra et al (and frankly improved on quite a few of them). The concert was a blast, my daughter became an instant Mary and Carl groupie. Carl had no idea I already knew Mary - why would he? - but it seemed perfect that they had connected and were working together: the virtuoso composer, conductor, arranger working with the virtuoso singer who could sing anything you threw at her, and make it sound fabulous.

On her Facebook page today Mary put it succinctly and perfectly: “…a great musician, composer - and showman….. It was 20 years ago that I first worked with him on concerts of theatre songs as well as film music - and it was he who first asked me to sing the Music of James Bond and with him I was fortunate enough to perform all around the world and we had a lot of fun together. He has left an incredible legacy of music composed for TV, film, and ballet - and additionally a sensational wardrobe of jackets!!”

Carl and soloists take a bow, with Mary Carewe at far right

Carl and soloists take a bow, with Mary Carewe at far right

Mary Carewe sings "Nobody Does it Better" with Carl conducting:

The Recordings

Carl has left an extensive discography. In 2009 he established his own label - The Carl Davis Collection - and was able to re-acquire the rights to many of his earlier recordings for re-issue, as well as make brand new ones. These are all CDs - and I will talk about a choice few of these later.

On vinyl there is a beautiful album of music taken from his music for the Hollywood series, presented in a nice gatefold on EMI, well worth acquiring.

For EMI he also recorded an excellent selection of film music by William Walton, not just including the famous Henry V Suite, but also lesser-known music, including previously unrecorded selections from the score to The Battle of Britain. All digitally recorded, I’m afraid, but still an essential purchase for lovers of this music.

One of the very best CDs of his film music has, alas, never been reissued. It is a selection of music from the series of Thames Silents he composed, the theatrical presentation of films like The Wind, The Thief of Baghdad, The Crowd, The Big Parade, Greed and Napoleon.

You get a real sense of the range and variety of music he composed for these films. Performed by the London Philharmonic Orchestra, it was issued by Virgin Classics, and you can find copies online. I have hoped for a long time this could be reissued as part of The Carl Davis Collection. (Silva Screen later put out a 2-CD set that included this plus selections from Carl’s other single disc recordings of material from certain of the silent film scores).

For more music from Napoleon, there is an early fine selection recorded by the Wren Orchestra, which Carl conducted at many theatrical presentations of the film. This was superseded in 2016 by an expanded version recorded with the Philharmonia Orchestra. You can also buy a blu-ray of the full film issued by the British Film Institute complete with plenty of extras, including Carl talking about his score. Although the final triptych is somewhat diminished on home video, this is absolutely the best way to experience the film short of a theatrical presentation (ignore the ghastly Coppola version with his father’s music which is still out there).

Another superb blu ray is of King Vidor’s The Big Parade, a chilling recreation of trench warfare in World War I. Carl’s score is one his very best, with massive drums accompanying the blasts of artillery.

Of the ballet scores there is a lovely recording of Aladdin on Naxos, a great place to start.

Carl recorded several James Bond albums. The one I prefer, with Mary Carewe (as mentioned above) is titled The Best of Bond and is with the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra.

An excellent sampler of his most popular scores, more recently recorded by Carl, is titled Heroines in Music. It includes generous suites from Pride and Prejudice, Cranford (a show and score I haven’t mentioned), and The French Lieutenant’s Woman.

If you must have the complete score for Pride and Prejudice (and why not - it whisks you away into Jane Austen's world), then that is available on a 1995 EMI release.

I wouldn’t describe the sound of any of these albums as being of top audiophile quality. I notice there is a propensity for a more reverberant acoustic on many of the film and TV score albums, which may have been added in post, partly to disguise smaller studio orchestras - a common practice. Not to my taste, but with film music albums you often have to accept less-than-perfect recording quality to get the material. The newly recorded collections often sound superior.

The most important thing is to dive into the catalogue. You will not be disappointed. Carl Davis leaves behind a unique legacy, and fortunately for us a large part of it was recorded and is readily available as physical product or on streaming services.

You can order CDs from the Carl Davis Collection directly here.

.png)