Bond in Orbit

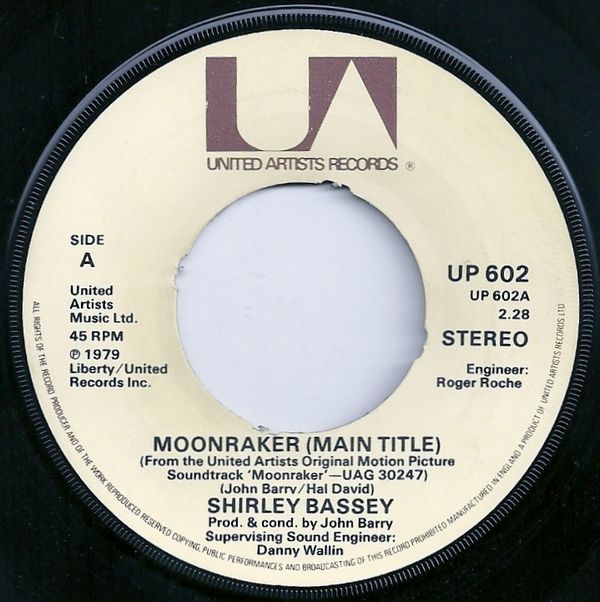

John Barry’s “lost” score finally gets the deluxe outing it deserves - and on vinyl too!

Japanese Poster Art

Japanese Poster Art

“Look after Mr. Bond. See that some harm comes to him.”

Hugo Drax

For many fans, the main harm done in Moonraker (1979) - the eleventh film in the official Eon-produced series of Bond films - was done to the franchise itself.

The film proceeded as a long, increasingly ho-hum procession of unsuccessful attempts by the film’s villain to knock off our favorite secret agent, played by Roger Moore in his fourth outing in the role. Channeling his inner Elon Musk, Sir Hugo Drax (played with an almost too deadpan laconic wit by the great Michael Lonsdale), is intent on wiping out humanity while relocating genetically superior humans to outer space who will then return to repopulate a “purified” globe. Even the iconic hit-man of The Spy who Loved Me (1977), Jaws, returns with his steel mashers and turns out to be all bark and no bite. The final insult: the film gives him a cute pigtailed girlfriend: they fall in love at their first shared smile - scored to the strains of Tchaikovsky’s Romeo and Juliet.

It was all a joke too far.

Bond aficionados’ response to the film’s devil-may-care descent into ever more elaborate stunts and chases, jokey asides and mounting irrelevant body count in exotic locations (that included the stunning Château de Vaux-le-Vicomte near Paris, Rio de Janeiro, and Venice), culminating in the whole enterprise blasting off into outer space in a sub-Star Wars rip-off, can be epitomized by the elaborate double-take by pigeons watching in disbelief as Bond sails through Venice’s St. Mark’s Square in a gondola that has conveniently converted into a hovercraft.

Ridiculous.

However -

and it’s a big “however”…

Those same Bond fans - and especially fans of the universe of Bond music - will agree that John Barry’s score for the film is one of the highlights of the series. This is simply one of Barry’s most lush, romantic scores, anchored by another iconic title song sung by (drumroll) Shirley Bassey, and a series of wonderful cues for the space sequences in particular. Space always seemed to bring out the best in Barry - as witness his iconic Capsule in Space/Space March from You Only Live Twice (1967), reworked for Blofeld’s Laser in Diamonds are Forever (1971).

1979 UK Pressing of Soundtrack LP

But no-one has ever heard the complete score in the manner it deserves to be heard. Not even in film screenings when, for some unaccountable reason, director Lewis Gilbert had the music dubbed into the final soundtrack mix in mono only! (According to Barry - there is some debate about this, see Neil’s comments below). And the original soundtrack record, then CD, only featured a tiny fraction of what Barry originally wrote and recorded for the film. (Even the 2003 CD reissue consisted only of those original album tracks, unlike many of the other Bond scores that were expanded for those 2003 releases).

2003 CD Tracklisting

So the arrival of the finally complete Moonraker soundtrack as part of La-La Land Records’ outstanding (and definitive) series of Bond remastered editions is to be celebrated as a major event for collectors of film scores in general, and of John Barry’s scores in particular.

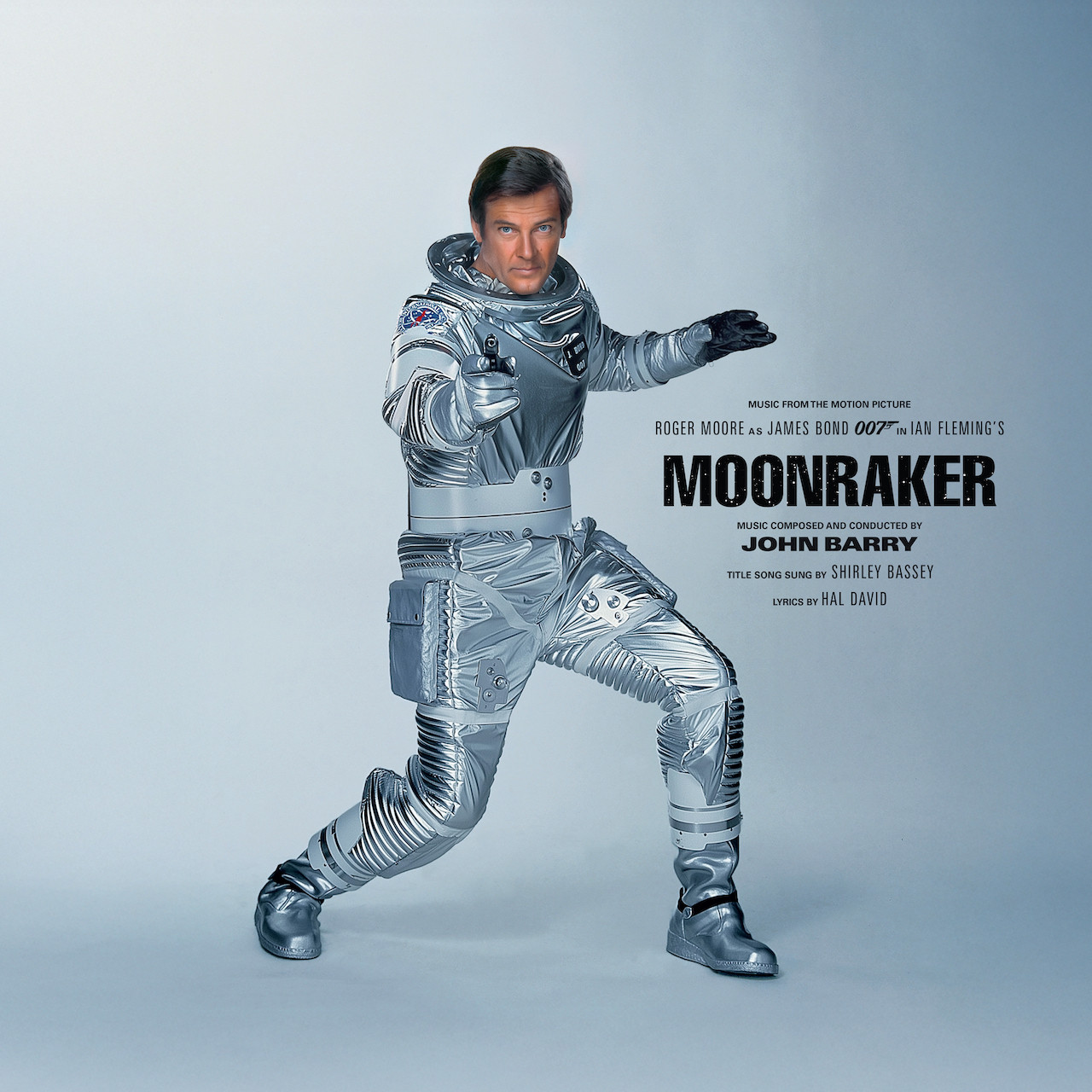

La-La Land Records' "Deep Space" Variant Vinyl Edition (007 Store Exclusive)

La-La Land Records' "Deep Space" Variant Vinyl Edition (007 Store Exclusive)

The Moonraker score is brilliant in opposing degree to the dumbness of the film. I hesitate to use the word “masterpiece” - but this score is right up there with Barry’s best, and is a very rewarding listen away from the film. Plus in this substantial sonic refresh it is a treat for the ears.

Acknowledging the importance of Moonraker within the Bond/Barry canon, and the significance of this finally complete release of the full score, La-La Land has chosen to follow up its 2CD release of last year with the second in what will hopefully be an ongoing series of bespoke limited edition vinyl releases, manifested in two different colored vinyl variants, one available direct from La-La Land Records, and one from the 007 store. No way I was going to miss out on having the vinyl version, even though I had already bought the double CD set. Which means you will get a full rundown on the score and how it sounds on both the CD and vinyl editions.

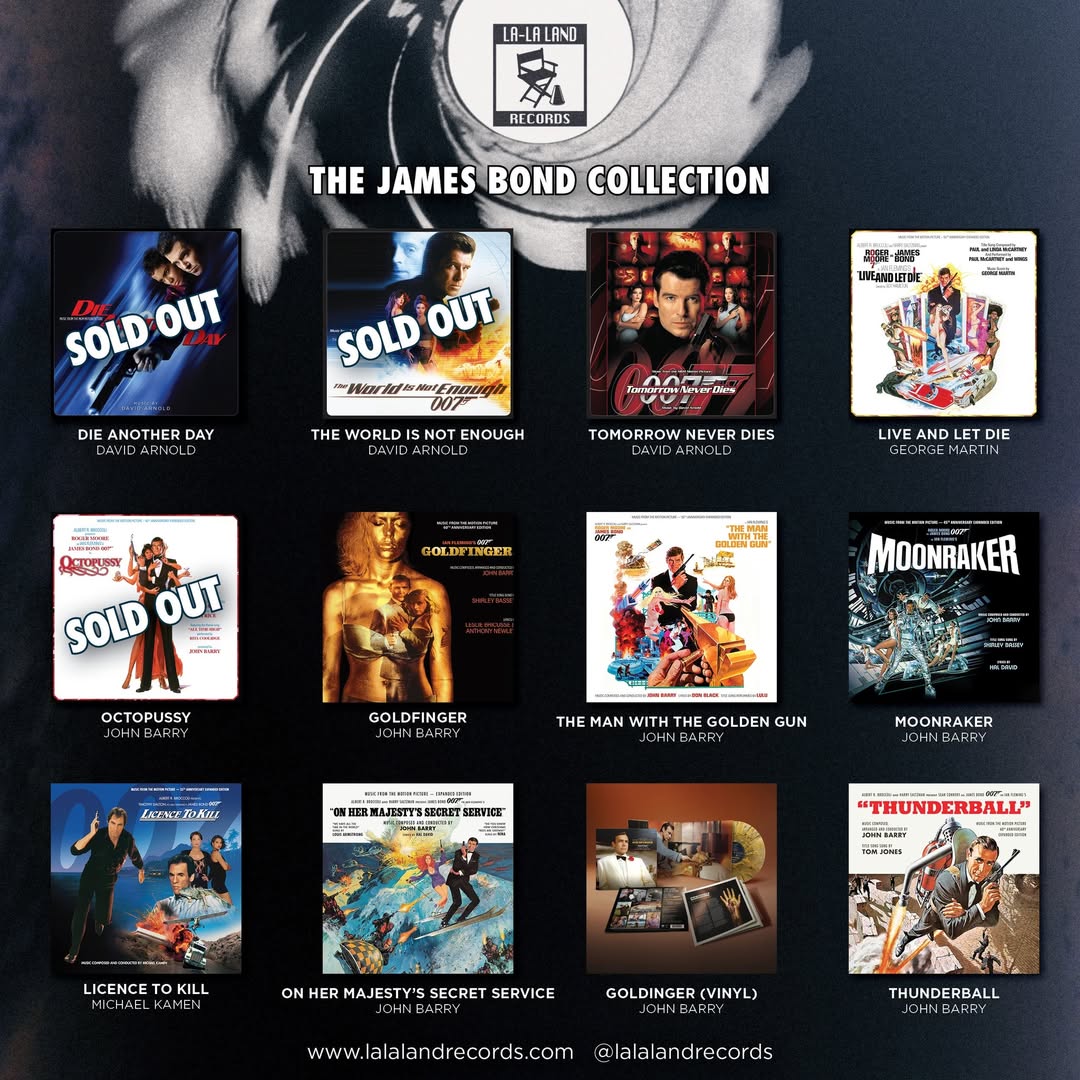

THE LA-LA LAND RECORDS’ BOND REISSUE PROGRAM

I have covered previous releases in this La-La Land campaign of reissues. John Barry’s iconic score for Goldfinger warranted two parts, Part 1 here, and Part 2 here. George Martin and Paul McCartney’s contributions to the Bond franchise with Live and Let Die were discussed here. Barry’s return to Bond with Octopussy is here. Barry’s The Man with the Golden Gun is discussed here.

Since then, La-La Land Records has released CD editions of Moonraker, plus On Her Majesty’s Secret Service and Thunderball - two more essential Bond/Barry scores. (Also Michael Kamen's score to Licence To Kill has appeared in a double CD edition). But I am going to hold off on reviewing those Barry scores until their equivalent vinyl editions also arrive - which I very much hope will happen. La-La Land’s commitment to creating bespoke vinyl editions is to be applauded.

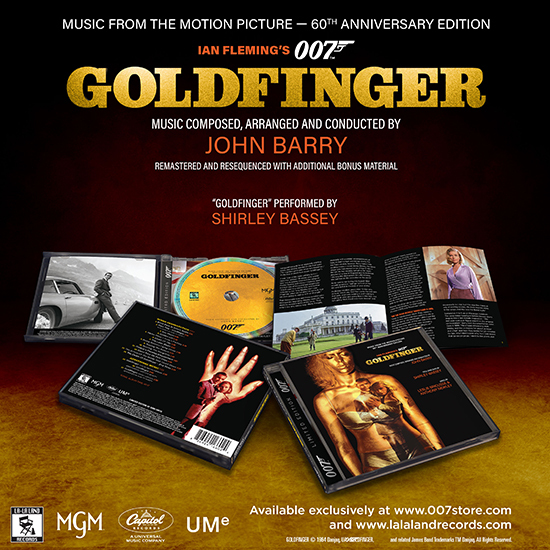

A vinyl edition of Goldfinger was released last year after I had reviewed the CD release. I decided to hold off on purchasing that simply because I felt the CD already sounded terrific, and I had early vinyl editions of the soundtrack which sufficiently scratched my Goldfinger vinyl itch. I am reliably informed by bona fide audiophile purchasers of that La-La Land vinyl edition that it is spectacular. Pressed on a single platter of colored vinyl, the sound - they say - is excellent, and obviously the booklet and artwork benefit from the larger 12-inch format. That edition (there were two variants, depending on whether you bought direct from La-La Land or from the 007 websites) is now out of print, but can be accessed on the used market at pretty exorbitant prices. Maybe I should have bought a copy after all… [As I wrote this, I succumbed to FOMO, and found a sealed copy at a somewhat more reasonable price… I’m only human, I guess… but have yet to listen.]

The one difference between the vinyl edition of Goldfinger and the CD version is that the vinyl edition only contains the complete score as reordered by the La-La Land team. You do not get the original soundtrack album and extra tracks - not a major sacrifice, to be honest. Completists will simply have opted for both versions.

GROUNDING THE ABSURD and SUSPENDING DISBELIEF:

THE HEAVY LIFT OF THE MOONRAKER SCORE

“Mr. Bond, you persist in defying my efforts to provide an amusing death for you.” - Hugo Drax

The huge financial success of The Spy who Loved Me (1977) paved the way for the budget extravaganza of Moonraker. Also the recent success of Star Wars and Close Encounters of the Third Kind inspired Bond producer, Albert Broccoli, to shelve plans to make For Your Eyes Only next; instead he opted to adapt Ian Fleming’s third Bond novel from 1955.

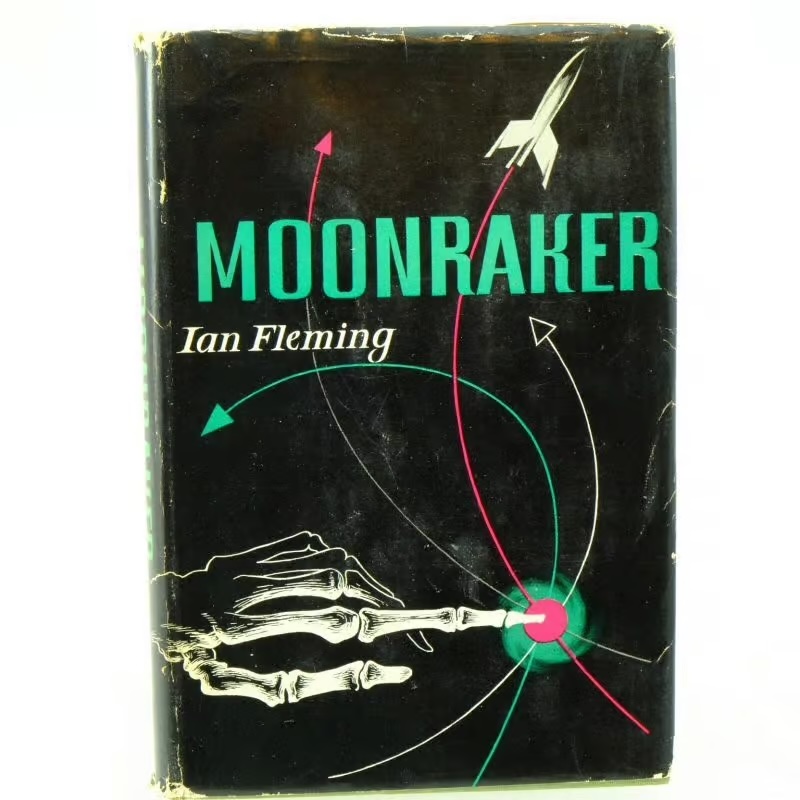

Ian Fleming's Novel - First American Edition

In contrast to the film, the book is a grounded espionage tale, albeit involving a nuclear missile with which the villainous Drax, a secret ex-Nazi, intends to destroy London.

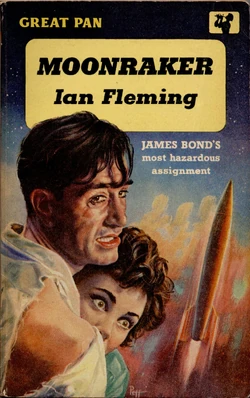

First Paperback Edition (1959) - the version my father owned and I first read

“Grounded” is hardly a word to apply to the film, which jettisons everything in the book apart from the villain’s name and proclivity for shooting up rockets. Instead the film fully embraces every extreme tendency of the franchise, using a formulaic narrative to justify a ton of globe-trotting and action sequences long on spectacle, short on credibility or genuine dramatic tension. The result was huge grosses but critical disdain, especially from hard-core Bond fans. Watching the film again recently I was able to understand why in some quarters it has clawed back an appreciation for its embrace of kitsch, even surrealism (a French château in the middle of the California desert!), but it remains for me and many a low point of the series.

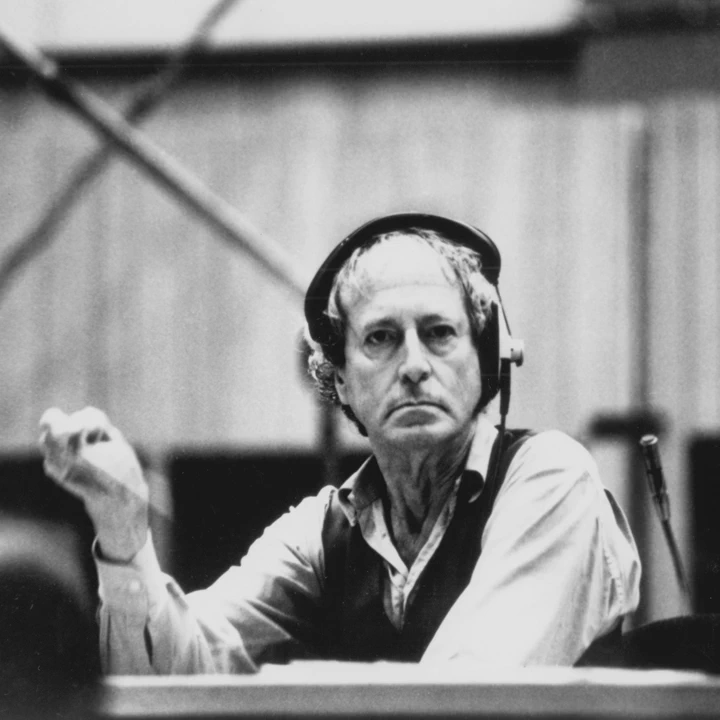

That the film succeeds at all is only because of the stunning score by Barry, who anchors the increasingly outrageous events onscreen with music of real emotional heft and weight (despite having to incorporate some more questionable cues from other famous works to help “sell” the film’s “jokes”). This was Barry’s first Bond score to move in the more lush, romantic and symphonic direction that he was adopting in his other film work, but which had always been present to one degree or another - think of the lyricism of Born Free (1966) or The Lion in Winter (1968). That shift would result in a string of Oscar-nominated and winning scores, including Out of Africa (1985), Dances with Wolves (1990), and Chaplin (1992). In his later years he optimized this style in new arrangements and recordings of his old scores - Moviola and Moviola II (the latter less successful than the exquisite first album) - and his late albums The Beyondness of Things (1999) and Eternal Echoes (2001).

John Barry

John Barry

The more serious, symphonic mode of Moonraker was in sharp contrast to the score for the previous Bond film, which Barry did not score because he was living abroad to avoid the UK’s punitive 82% tax rate. Interesting, because the score for the more “anchored-in-a-conceivable-reality” of The Spy who Loved Me was considerably more lightweight, the work of Broadway’s then King (via his hit show, A Chorus Line), Marvin Hamlisch. Hamlisch’s Bond outing incorporates disco elements (albeit discreetly), plus synthesizers, whilst wisely retaining elements of the Barry palette. It’s actually a fun score, with one of the best title songs (Carly Simon taking Nobody Does It Better to the Oscars and to No. 2 on the American charts), and I especially dig his reimagining of the Bond theme as a disco rave…

To avoid tax complications enmeshing many of the principal players if they made the film in the UK - including Roger Moore, Barry and even Cubby Broccoli - it was decided to move the whole production to France. This meant Barry was back on board.

From the get-go Barry had big plans for Moonraker. The scale of the film prompted him to consider revisiting a method he had used for The Whisperers in 1966, where he had written the music ahead of the film being finished, and then adapted it into a form that would work with the picture. This is rarely done in movies, for all the obvious reasons, though when it has been done it can result in something quite special - for example the Ennio Morricone scores for Sergio Leone’s films (the Dollars trilogy, Once upon a Time in the West), Philip Glass’s music for Koyaanisqatsi, and John Williams’s music for the final scene of Speilberg’s E.T. the Extra Terrestrial.

Jon Burlingame, in his essential survey The Music of James Bond, takes up the story:

Barry’s original idea was to write an eight-movement symphonic work and record it with the prestigious Orchestre de Paris while production was still under way.

“We know the nature of the Bond stuff,” Barry told an interviewer in late 1978. “Why don’t I use that time in front to make it a more substantial and more important part of the picture? … By doing it this way, we get all the music that’s in the movie plus a little more - but it’s in forms that are far more attractive to listen to. We’ll have the score finished by the time they finish shooting the movie.”

He had hoped to turn it into a two-LP set à la the colossally successful Star Wars album; Broccoli agreed, Barry said, and was going to talk it over with United Artists.

It was an ambitious, brilliant concept. It went nowhere.

SINATRA SINGS BOND?

Nancy Sinatra (who sang the theme to You Only Live Twice) with her dad...

Nancy Sinatra (who sang the theme to You Only Live Twice) with her dad...

Yup, you read right.

One of the more curious corners of Bond lore involves the fact that Ol’ Blue Eyes almost followed in his daughter Nancy’s footsteps (she recorded the title song for You Only Live Twice).

Approached by his pal Albert Broccoli to lend his pipes to the title song for Moonraker, the process got to the point of him listening to a demo of the song furnished by Barry and his lyricist Paul Williams, who had already collaborated on a song for Barry’s score for The Day of the Locust. The full version of this bizarre tale does not make it into the La-La Land notes furnished by Burlingame, but it’s worth quoting from his book:

Williams met with Sinatra and his long time aide "Sarge" Weiss at Sinatra's office on the old General Services lot in Hollywood. "The amazing thing is, there was nothing there to play the demo on,” Williams recalled. “Sarge finally came up with a rusty old portable radio with a cassette player, mono, salty from the beach. And that's what Frank heard the song on. And he loved it. ‘Marvelous, Mr. Paulie, marvelous.’ This from Music Royalty to me, and I was thrilled,” Williams said.

Sinatra opened a briefcase, which contained his datebook (and a .38, Williams noted), and they discussed possible dates for recording. “I left his office walking on air. We were all delighted. Then Frank was out. I don't know what happened but, I was told at the time, Cubby and Frank had a big fight and he was history.

No one knows to this day why it all fell through, and the rumored fight is unlikely since Broccoli and his wife palled around with Frank and his wife at the film’s premiere.

In the meantime Barry had a score to write and record, which he did with French musicians and a small choir numbering some 100 musicians in total in the renowned Studio Davout in Paris, the scene for classic film scoring sessions by Francis Lai (A Man and a Woman), Michel Legrand (The Young Girls of Rochefort) and Serge Gainsbourg, and for albums by Karlheinz Stockhausen, Archie Shepp, Keith Jarrett, Nico and The Cure - to name but a few.

Studio Davout in Paris - 1973 Recording Session

Studio Davout in Paris - 1973 Recording Session

Barry imported his own trusted group of English musicians for the rhythm section, and engineer Dan Wallin, who worked with Barry regularly between 1975 and 1986.

Wallin (quoted by Burlingame):

“It was an old movie theater. The room sounded quite good, but the underground train ran right underneath it, and every time it ran through, it would vibrate and you'd have to do another take.”

Owing to union rules, Wallin was not allowed to physically touch the console, and instead had to “guide” the French engineer’s moves.

“I practically moved his hands on the faders, and I finally got it to what you heard in the end. But by the time we got all through it was not a lovefest.”

Sessions over, with Wallin doing some fine tuning to the mix in London, Barry returned to the States - still without his title song.

Next up to the microphone was Johnny Mathis, and a demo was made, but immediately afterwards Barry decided it did not cut the mustard. Briefly the possibility of Kate Bush - then a newly discovered star in the pop firmament - was floated, but scheduling conflicts nixed that idea (just imagine that song!)

With barely a month left before the premiere, Barry bumped into his old comrade-in-Bond-arms Shirley Bassey in the Polo Lounge in the Beverly Hills Hotel.

Barry (quoted by Burlingame):

“And I said, ‘Oh my God, do you want to do another Bond song?’ I got Cubby Broccoli on the phone and we were in the studio within a week. It was virtually the same arrangement, everything the same.”

Except the lyrics. Barry decided to go in a new direction, and Williams was not onboard. Barry turned to Hal David who had come up with the lyric for We have All the Time in the World for On Her Majesty’s Secret Service.

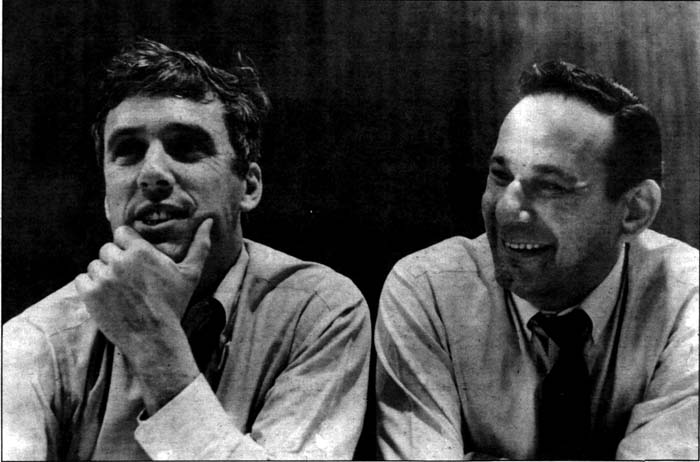

Hal David (r.) with his writing partner Burt Bacharach

Hal David (r.) with his writing partner Burt Bacharach

Without seeing the script or any footage, David flew to New York and in a couple of days the two hammered out what was to become a Bond classic.

David (quoted by Burlingame):

“John really couldn't play piano to any extent… He could get chords, and a melody, but not together and not in time. He tried to play it, but I think he explained it to me in terms of ‘and this is repeated…’ Anyway, I'm pretty musical myself, and I was able to get the whole melody. I wrote the lyric over the weekend, because they were going to record on Monday or Tuesday… I had no idea what a ‘moonraker’ was. It's kind of mystic” he said of the song, “and probably because I didn't see the movie, I couldn't be more specific.”

Barry conducted the sessions for the song with Bassey on the Warner Bros. scoring stage.

Bassey herself never really felt it was “her” song, but she sings it with such complete emotional commitment that it leaps out of the speakers, creating a sense of mystery and allure which is very different from her previous Bond outings - Goldfinger and Diamonds are Forever. For me it has long been a highlight of the Bond title song canon - and I can’t imagine that even a Sinatra version could have been in any way preferable.

Shirley Bassey

Shirley Bassey

Bassey + Barry = Bond!

THE MOONRAKER SCORE FINALLY COMPLETE

Hugo Drax (Michael Lonsdale) and his henchman assassin Chang (Toshiro Suga)

“James Bond. You appear with the tedious inevitability of an unloved season.”

Hugo Drax

La-La Land Records' Double CD Edition

La-La Land Records' Double CD Edition

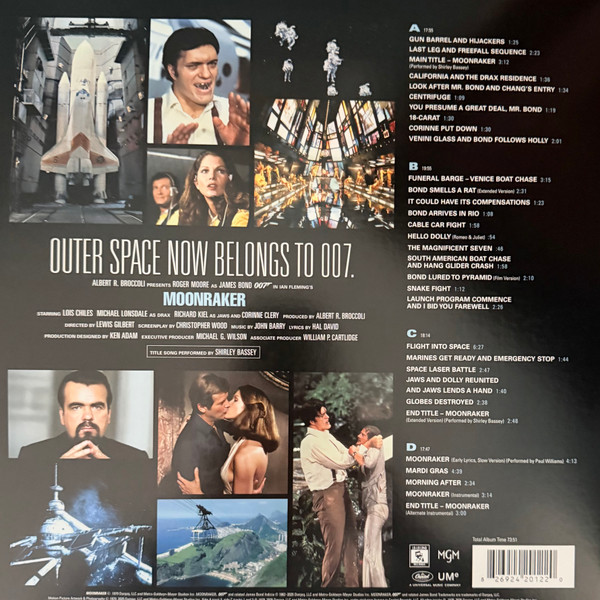

For the first time the complete score is presented on CD1 of the La-La Land reissue, and on sides 1-3 of the vinyl. Side 4 of the vinyl offers a selection of additional tracks sampled from across the CD release (which has literally everything heard in the film, including those “joke” cues drawn from classical works), and includes the demo of the Paul Williams version of the title song, with Williams singing. This is the demo that Sinatra heard.

Track Listing for Vinyl Edition

Track Listing for Vinyl Edition

While the original soundtrack album (presented complete on disc 2 of the double CD set) represents a mere suggestion of the riches contained within the complete score, now we can all hear Barry’s conception whole, presented in chronological order as heard in the film - and it’s a wonderful listen.

The opening gun barrel sequence favors Barry’s move towards having the famous Bond theme played on strings rather than guitar, something he instigated with The Man with the Golden Gun.

Please Note: Video clips do NOT feature La-La Land remastered sonics (except where indicated in video description).

The Spy Who Loved Me set the highest bar for Bond pre-credits sequences, with the breathtaking ski-jump turning into a free fall and parachute drop performed by Rick Sylvester. Moonraker went all-in with an equally impressive free-fall from an airplane and subsequent mid-air fight, with Bond and his would-be assassins battling for the lone parachute. Barry’s music is used sparingly but effectively, although we get an indication right upfront of the jokey tone the film is going to adopt as hired assassin Jaws plunges into a circus tent to the accompaniment of jaunty circus music.

Fortunately, Shirley Bassey’s mesmerizing title song follows immediately, re-establishing a mood of sensual mystery and that quintessential “Bond” feel. Nobody does it better…

A comparison with Paul Williams’s demo version immediately reveals why his lyrics were dropped once Sinatra left the scene. They are simply too prosaic and almost cartoonish in both their references to “Lady Luck” (obviously a sop to Frank), and awkward rhyming structure. Hal David’s more allusive, mysterious take is far more suited to Barry’s romantic style, complete with his characteristic violin arabesques played in counterpoint to the main tune, a device that harkens back to You Only Live Twice, and which create for the listener a sense of being enveloped by the music’s sensual caresses.

Everywhere Barry’s ability to establish mood and situation quickly is on display, from enhancing the imposing grandeur of Hugo Drax’s French Château standing incongruously in the middle of the California desert (“California and the Drax Residence”) to the mounting threat of “Centrifuge”. The exquisite “Moonraker” theme weaves its way throughout the score, especially in scenes of Bond’s amorous trysts (“You presume a great deal, Mr. Bond”). “18-Carat” demonstrates Barry’s economical but always vivid use of orchestration to highlight a dramatic moment.

Barry hits “local color” mode for his cue “Bond arrives in Rio”, blending in a Latin atmosphere. This moves even more to the fore in the source music cues on side 4, “Mardi Gras” and “Morning After”, which are so good you wish they had been foreground elements in the film.

However, the score really hits its own distinctive stride with “Bond Lured to Pyramid”, a surreal sequence in which Bond - in the middle of the jungle - suddenly finds himself being led towards the launch base for the Moonraker operation by a parade of scantily-clad women who wouldn’t look out of place in the pages of Vogue. Barry’s music manages to be both ethereal and erotically charged here, blending in a wordless choir to great effect. (In some film studies program somewhere there is a great thesis to be written on surrealism in the Bond movies - mind you, it could have been written already).

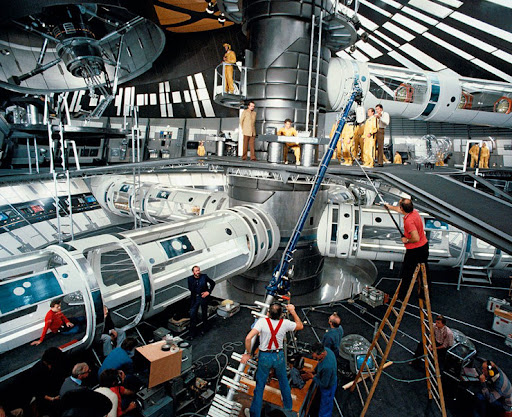

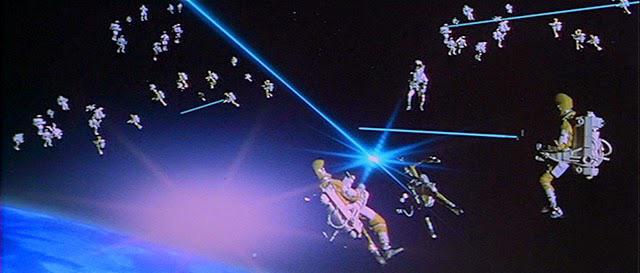

Vinyl side 3 kicks off the outer space sequence with the epic six-minute cue “Flight into Space”, accompanying Bond and Dr. Goodhead’s flight aboard one of the shuttles towards Drax’s orbiting space station. It is a mesmerizing blend of a slow march reminiscent of the famous “Capsule in Space/Space March” cue from a decade earlier, with interpolated rich, heavy brass chords (a specific harmonic sequence that recurs throughout the score like a Wagnerian leitmotif). The music brilliantly conveys the required sense of awe and mounting dread at the threat the space station represents.

Sequence as it appears in the film (but cut short):

Sequence with restored audio isolated (full-length):

As with John Williams’s music for Star Wars and Close Encounters of the Third Kind, Barry’s score is essential to selling the audience on what is essentially unbelievable and even a bit ridiculous.

This cue provides the engine that powers the following sequences of fights in outer space, and Bond and Goodhead pursuing and destroying the life-annihilating globes as they re-enter the atmosphere. The space laser battle is a particular highlight, incorporating some very subtle but effective use of synthesizers.

Note that all this action is scored with slow-moving music of enormous grandeur - the complete opposite of what most composers would do today. Barry was so smart to focus on the otherworldliness and larger-than-life quality of these scenes rather than trying to inject artificial “busy-ness” into the action (which, being weightless, is mostly slow-moving anyway). A true master at work - and an interesting point of comparison with his approach to the underwater battles in Thunderball a decade-and-a-half earlier.

RESTORING THE ORIGINAL SOUND OF MOONRAKER

“At least I shall have the pleasure of putting you out of my misery.”

Hugo Drax

Hugo Drax (Michael Lonsdale)

Despite having a beautifully designed, assembled and annotated booklet accompanying both the CD and vinyl releases, there is no information regarding the details of how this new edition was created. Therefore I reached out to producer Neil S. Bulk, who has shepherded all of these Bond reissues. He referred me to his detailed blog post on the topic of Moonraker (and much of his other soundtrack work besides), and then answered further questions I had. (Soundtrack and Bond fans will want to read the whole blog entry - and I am sure will recognize much of their fandom in Neil’s account of his history with the film).

I began by asking Neil about the sources used for this restoration. You will also see he refers to Mike Matessino, who provided the mix for the reissue.

The entire album was sourced from high-res 48 khz/24-bit transfers of 2" analog tape. The transfers were done in 2015 and provided by MGM. No detective work was required as it was all there. There wasn't any damage at all to them, and the transfers were also resolved, which meant they ran perfectly at film speed.

The 2" tapes were copies made of the selected takes, so I didn't have any outtakes, just the final performances of every cue intended for the film. This seems to be the way Pinewood Studios operated in those days. When Mike Matessino produced the latest issue of "Superman: The Movie" for La-La Land Records amongst the pile of tapes were dubs of the selects in the exact same kind of boxes as "Moonraker."

Since I only had selected takes in good condition the biggest challenge was understanding the French engineers' vocal slates! Initially I didn't have photos of the tape boxes so all I had to go by to ID the cues was either the engineer or the music itself. Luckily I'm familiar with the film, so I could place where much of the music was supposed to go, but there are six completely unused cues in the film and I didn't know what they were meant to accompany. MGM was able to provide photos of the boxes and eventually my high school French kicked in and I could sequence the score in order. I then worked with my friend Harry Frishberg with those six unused cues and we synced them to the movie so we could understand exactly what they were.

The Paris-recorded 2" 24-track score tapes were laid out with a 3-track LCR mix on the first three channels and then the separate instrument feeds were on the remaining tracks along with sync. Generally I like to work with an original mix as it requires less decision making and is closer to what the artists intended. While this 3-track was definitely the film mix and was an improvement over the original album mix, it didn't seem good enough for CD, especially "Space Laser Battle" and Mike Matessino and I knew it could be better. We did refer to those mixes for level and placement. This is most obvious with the track "Funeral Barge — Venice Boat Chase." Mike's initial mix wound up as the "Alternate Mix" on the album. I like it a lot, but for the "Score Presentation" I felt we should hew closer to what the artists intended.

Dr. Goodhead (Lois Chiles) and Bond (Roger Moore) weightless on Drax's Space Station

Dr. Goodhead (Lois Chiles) and Bond (Roger Moore) weightless on Drax's Space Station

I had some questions about specific tracks, including the various versions of the title track and the two source music cues, "Mardi Gras" and "Morning After”, which have a very different vibe and somewhat different sound from everything else. Were these recorded in France or America - and who was singing? It sounds like a very different group from the regular choir used for the rest of the score.

The entire score, including these two songs, was recorded in France. When the song with the Paul Williams lyrics wasn't working out, the main and end titles as well as both takes of the "Intro To End Title" were recorded in America about 6 weeks before the release of the film.

The biggest surprise was uncovering the Paul Williams version of the title song. Jon Burlingame had written extensively about this in his book "The Music of James Bond" but I never expected to hear it, especially from the original multi-track tapes. Remember, at this point I didn't have any documentation to explain what was on the transfers, so I was going in blind. Yet here it was and I immediately called Jon when I made this discovery. I'm happy to report that we got all of the approvals needed to include two versions of this song on the release.

A week before Shirley Bassey recorded her version of the song there was a session for another version of the song. It's been reported that Johnny Mathis was going to record the song, but I never saw any documentation regarding this and the tape box for those sessions specifically says there's no vocal on them. The "Alternate Instrumental" tracks on CD disc 2 are from those abandoned recordings.

Initially I thought we should present "Mardi Gras" without the crowd, but Mike Matessino convinced me otherwise and I'm glad he did. [Me too! - MW]. There wasn't any documentation about the performers.

Filming on the Space Station Set

Filming on the Space Station Set

I see no mention in Jon's notes or book of the use of synthesizers and/or electronics in the score, yet clearly either or both are being used in the track “Space Laser Battle”. Can you throw any light on this, both from the original sessions and score, or from studio notes, or from listening to the raw tracks?

"Space Laser Battle" absolutely has synth, recorded in France with the orchestra. The synth created an unpleasant buzzing around 8 kHz. We can easily deal with an issue like that now, but maybe it wasn't so easy in 1979. So in the film mix this noise came through with the orchestra. On the album, I think the high frequencies were rolled off entirely and they also buried the synth in the mix.

Space Laser Battle

Space Laser Battle

I asked Neil about the mastering chain for the CD and for the vinyl…

I reached out to Doug Schwartz, the mastering engineer, for more on this. Here was his reply.

“‘Moonraker’ was mastered using WaveLab software and a variety of restoration software, equalizers, and level enhancements. The program chronologically follows the dramatic tension of the film and so was intended to give the listener a musical representation of the picture. The audio for LP was provided without further compression or equalization, with the understanding that the cutting engineer would use best judgement to accommodate the limitations inherent in the lacquer/vinyl process."

Doug provided the 48 kHz-24-bit digital sides which were then mastered for vinyl by Bobbi Giel at "Welcome to 1979." The initial test pressings weren't up to our usual standards and Bobbi was great to work with. After listening to revised reference lacquers and then new test pressings I was thrilled with how it all came together.

The records were pressed at Waxwork Records.

Jaws (Richard Kiel) and Friend... (Dolly, played by Blanche Ravalec)

Jaws (Richard Kiel) and Friend... (Dolly, played by Blanche Ravalec)

After going through this entire process, do you have any technological insights into why the 2003 CD version sounds so goddamned awful, or why the original vinyl release isn't much better. (The CD sounds like it uses some new added reverb amongst other things...)

This is the great mystery. Barry seemed to think the album mix was good. There was an interview where he complained about the music sounding monaural in the film and the record was how it should sound. I disagree. I don't know what he saw, but I've seen vintage prints and they were clearly stereo (this was the first Bond film released in Dolby Stereo) and as I stated above, I heard the 3-track music mix on the tapes. Those mixes match what's in the film and do not sound like the record at all. The original album mix is practically monaural with terrible dynamic range and Mike and I didn't care for it so we didn't feel obligated to recreate them. The album was referenced for take selection and I matched the timings of the cue combinations. In a few instances we kept the intent of the album mix, for instance the end title song as heard in the film has an overlay recorded by Michael Boddicker that is not on the original album.

The La-La Land Records "Orchid" Variant Vinyl Edition

The La-La Land Records "Orchid" Variant Vinyl Edition

HOW DOES THE LA-LA LAND RECORDS REISSUE SOUND?

In a nutshell, superb, superior to any previous version of the score, and the best this score is going to sound short of an all-analogue mix from the analogue masters.

So why doesn’t this get a higher score on the SOUND rating scale (although an 8 is pretty damn good)?

It is simply a fact that truly great sounding film scores are something of a rarity, at least when you compare them to the legendary records from the golden ages of RCA Living Stereo, Mercury Living Presence, Decca and EMI. These are my benchmarks for recordings of orchestras, as are the new DG Original Source and Decca Pure Analogue reissues.

True, there are genuine audiophile soundtrack records out there, including the RCA Classic Film Series, and the DCC versions of For Whom the Bell Tolls and Music by Erich Wolfgang Korngold. I will also include here John Barry’s Dances with Wolves on ORG, and Moviola, both recorded by the great Shawn Murphy.

But especially during this period of the late 1970s through the 80s and beyond, with studios and record companies switching out mixing desks and older electronics to accommodate ever-increasing numbers of channels and tracks, no matter what the sonic impacts of prioritising flexibility over quality, as well as moving to digital (Moonraker was recorded all-analogue), the sound quality of orchestral film music became even more variable. One of my pet peeves became the drowning of orchestras in oceans of reverb, often done to make the orchestra seem larger than it actually was. (Budget pressures were always making it harder to hire truly grand-sized symphony orchestras - unless you were John Williams).

The Achilles heel of Moonraker is the string sound, specifically the violins. I kept trying to figure out what sounded just a little bit “off” about the violin tone. In essence, there is a somewhat hooded quality to the higher string tone, which I think is a result of the studio acoustic itself and the microphones used. Similar (but also different) shortcomings afflict the violin and string sound in DG recordings, even persisting into some of the Original Source remixes. What’s going on in the Moonraker sound is nothing that should deter you from buying the release, and is actually a huge improvement upon any previous version - it just means I can’t quite justify going with a “9” on the sound rating. Neil Bulk and his team have worked wonders with the orchestral sound in general, and the ear quickly adjusts to the balance of the Moonraker recording. I will say that the vinyl version ameliorates the string sound even more than the CD, with the violins sounding distinctly sweeter.

Overall, Bulk and his team have delivered a rich, burnished orchestral sound, especially with the brass - a key element in Barry’s sonic palette - with tremendous dynamic ebb and flow. The bass rumbles mightily. On the Side 3 sequence in outer space, you will be constantly pushed back in your seat by the power of those huge orchestral chords, dominated by the brass. The choir is beautifully balanced with the orchestra, adding the requisite touch of mystery and awe when called upon.

Bassey’s title song emerges with its finery nicely spruced up, her voice an eternal wonder. The end title disco version remains a curio of its time, but it’s fun to have.

Bond and Dr. Goodhead

Bond and Dr. Goodhead

I must say that other highlights include those two source cues for the sequences in Rio, “Mardi Gras” and “Morning After”, where the French musicians really let their hair down. I am so glad Mike Matessino was able to persuade Neil to keep the vocal contributions - it’s all so much fun.

Other cue highlights include the Goldfinger-esque “18-Carat”, the eternally seductive “Bond Lured to Pyramid” and all the outer space cues. In this remastering “Flight into Space”, an uncharacteristically long cue, has enormous cumulative impact, and vividly demonstrates how when a director lets a composer off the leash, and lets the music do the talking, the results can be extraordinary. Having the synthesizers reinstated to “Space Laser Battle” is a real treat.

My double LP pressing in the Orchid color variant was exquisite to look at spinning on the old turntable, was very quiet, but betrayed the odd tick and pop even after cleaning. Nothing that interfered with my enjoyment, and the vinyl for me is absolutely the format with which to enjoy this release, in large part for that sweeter violin tone, but also for its overall sonic presentation which simply felt more immediate and full, adding just a touch of extra engagement over the still fine CD. Of course with the CD you will get even more music, but a lot of that is repetition (like the Original Soundtrack release). I will say that the CD allows you to dissect everything that’s going on sonically with more precision, and many will prefer that, but for me the organic whole of the musical experience presented by the vinyl is preferable.

Plus the larger format presentation is an argument in and of itself, with photos and text benefitting enormously. The iconic photo of Roger Moore on the cover is a nice alternative to presenting the poster, and the frame blow-up on the inside gatefold is rendered beautifully. The always immaculate design and curation of La-La Land’s booklet really shines in its LP incarnation. The vinyl package is the work of designer Jim Titus (Dan Goldwasser designed the CD version). Both designers add a distinctive touch to the release. With Bond, design is an integral part of the game.

Like the Goldfinger vinyl release before it, the limited vinyl edition of Moonraker (700 copies at La-La Land, 300 at The 007 Store) will sell out. If Bond and Barry is your thing, do not hesitate to pull the trigger, sooner rather than later.

James Bond will Return…

Limited Edition Vinyl (and CD) available for purchase directly from La-La Land Records. I just got an email alert that stock on the vinyl is low, so now's the time if you want a copy.

Alas, I just found out the LP is now sold out at the La-La Land site. It's not clear what its status is at the 007 store. Obviously it will be available from after-market sellers.

Let me also emphasize that the 2CD version sounds excellent, gives you more music, and is still available - although it too is a limited edition and will eventually sell out.

.png)