David Murray Soars with the Birds

The great tenor saxman nabs his first major label in 50 years

It’s only taken 50 years for David Murray to record an album for a major label, but here it is: Birdly Serenade, laid down with his current (and sizzling) quartet, on Impulse, which is owned by Universal Music Group—one of the “Big Three,” along with Sony and Warner, and thus about as major as they come.

Murray, born and raised in Oakland, was just 20 when, in 1975, he left Pomona College for New York and made an instant splash on the downtown loft scene, the flourishing center of the city’s avant-garde art movements. In his first few years, he cut a dozen albums (with the likes of Don Pullen, Lester Bowie, Fred Hopkins, and Andrew Cyrille), then joined the World Saxophone Quartet (whose three other members—Julius Hemphill, Oliver Lake, and Hamiet Bluiett—were a decade his senior), which evolved into one of the stellar jazz bands of the 1980s. Meanwhile, in the same decade, Murray recorded at least 30 albums under his own name, fronting ensembles of various sizes, emerging as one of the giant jazzmen of the era (in all, he has been the leader on about 100 albums)..

During his peak output, in the late ‘80s through mid ‘90s, his visibility in record bins was heightened as his two main labels at the time had prominent U.S. distributors—the Italian label Black Saint through Polygram Special Imports and the Japanese DIW through Sony (at least for a little while). Still, not until Birdly Serenade has Murray been signed to record for a major label.

Those who know his early work will be pleased to learn that, now at age 70, he sounds pretty much the same as he did…if not quite 50 years ago, then certainly 40.

His early concerts and albums were deeply rooted in the avant-garde, clearly influenced by Albert Ayler, Archie Shepp, and Ornette Coleman—though he was developing his own sound, marked by searing loop-de-loop improvisions, modeled to a degree by his idol, whose recordings prodded him to switch from alto to tenor saxophone in his teen years, Sonny Rollins.

By 1980, he broadened his repertoire to include ballads—deeply romantic escapades (of his own composition, like most of his songbook). He could be just as frantic in his improvisations, racing through thirty-second notes like nobody since Coltrane, and tracing even his basic melodies through intervals of riveting harmonic complexity, but he coated all of this with a smoky, barrel-chested tone and sweet vibrato reminiscent of Ben Webster. (You can first hear this shift in his octet album of that year, Ming.)

Through that decade, and into the mid-90s, he sometimes released a handful of albums in a single month, and at least half of them stand as classics. I saw him play with his big band nearly every week at the Knitting Factory, in downtown New York, and he could be spotted in other clubs playing, as a leader or sideman, with a vast assortment of bands. Then in the mid-‘90s, he decamped to Paris, reemerging only occasionally, often with various exotica: a group featuring Gwo-Ka masters from the Antilles, a South American big band playing Latinized arrangements of Nat King Cole, and other experiments.

About eight years ago, he moved back to New York, dipped a toe back into the scene, careful at first not to spread himself too thin, trying out a variety of bands, in search of the right mix.

It took him a while, but I think he’s found it, especially in his pianist, Marta Sanchez. (When they first played together in Europe, he assumed she was a Spaniard and was delighted to learn that, though she grew up in Madrid, she lived in Brooklyn and was thus available for sessions). Rooted as much in Ravel and Debussy as in Wayne Shorter and Andrew Hill, Sanchez can dart across the keyboard with astonishing agility, never for showman’s sake, always to serve the music, shining light on angles and colors that weren’t apparent before, enriching the song with new layers of joy and complexity. (Sanchez’s 2022 quintet album, SAAM: Spanish American Art Museum, which I reviewed on this site, is a masterwork.) Luke Stewart and Russell Carter, on bass and drums respectively, anchor the excursions and interplay with heady confidence.

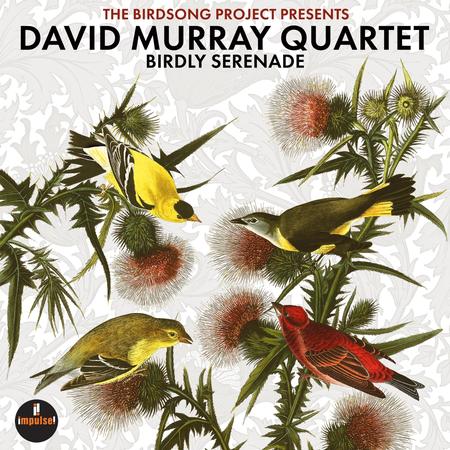

This album’s odd title, Birdly Serenade, stems from its sponsorship by the Birdsong Project, “a community dedicated to the protection of bird life” (I’m quoting from the liner notes) that has assembled 200 tracks of bird-celebrating music on its website. But don’t be misled into thinking that this is some New Age airiness. No, it’s as drenched in vim, vigor, and verve as any David Murray album. In fact, I’d say it’s his best in a couple of decades. (You’d have to go back to Sacred Ground, recorded in 2006 with Ray Drummond, Andrew Cyrille, Lafayette Gilchrist, and a track with Cassandra Wilson—though his 2015 trio album, Perfection, with Geri Allen and Lyne Carrington, is also worth noting.)

Murray goes along with the project’s game, musing on bird songs in the liner notes. Some of the album’s eight songs have “bird” in the title, but a couple of them are clearly references to Charlie Parker (not one of Murray’s big influences, so maybe he moved himself to explore bebop harmonies in homage to the avian theme). Even the three songs with lyrics (written by Murray’s wife, Francesca Cinelli), though charming, are only peripherally about birds. I should say here that they’re sung with great spirit and beauty by Ekep Nkwelle—a new name to me, a limitation that I plan to remedy soon.

Now the part that many of you have been waiting for: The sound quality—engineered by Maureen Sickler, mixed by Stewart Lerman, mastered by Greg Calbi, and cut to LP by Ryan Smith at Sterling Sound—is excellent. Murray’s horn comes off as vivid and 3D as it has on all but a few of his albums. (Notable exceptions are Sun/Moon and Plumb, the two he recently made for the J.M.I. label, which records, mixes, and masters all of its albums in analog.) The bass is properly wooden and plucky. Most eyebrow-raising is the piano, which is stunningly present—the percussive keys and the blossom of overtones. This is stunning because the album was recorded at Rudy Van Gelder’s studio, and pianos were often RVG’s weak point, even on some of his otherwise stellar albums on Blue Note and Impulse (the label’s original indie incarnation) from the early 1960s. Sanchez played the piano in the same place where the pianists of yore played it. I wonder what Sickler did differently. (If I find out, I’ll let you know.)

The CD also sounds good, but the LP much better. No doubt improving matters, the producers at Impulse! spread the music of this roughly hour-long album across the four sides of two vinyl discs (just 12 to 18 minutes per side), leaving plenty of blank space along the inner grooves. Very generous!

Meanwhile, it’s good to see David Murray sounding in peak form in such a prominent showcase.

.png)