Death and Resurrection - The Original Source Offers a Glimpse of Heaven

Mahler’s Epic Second Symphony Finds New Sonic Illumination

“There is the great question: why did you live? Why did you suffer? Is it all nothing but a huge, terrible joke? We must answer these questions in some way, if we want to go on living—indeed, if we are to go on dying! He into whose life this call has once sounded must give an answer.”

Gustav Mahler

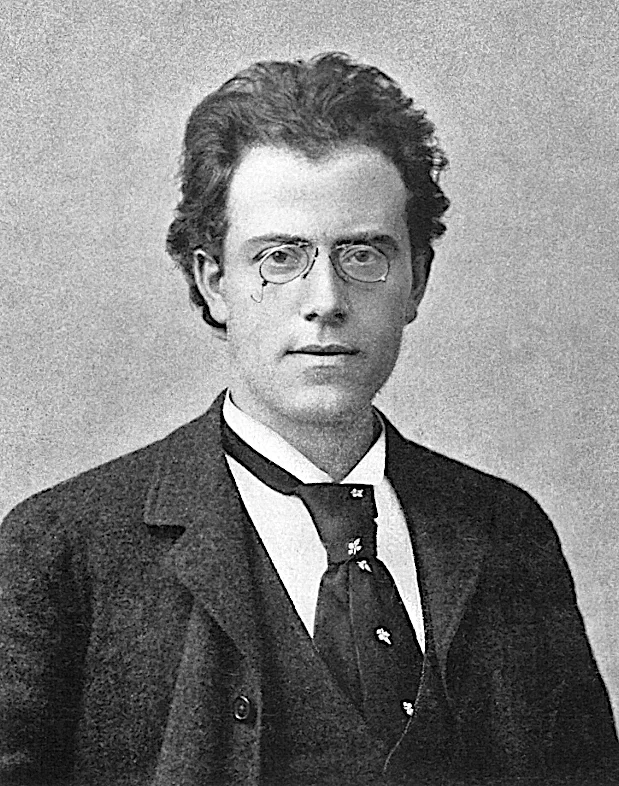

Increasingly confronted by intimations of mortality, Gustav Mahler turned to thoughts of death even in the midst of life.

Gustav Mahler in 1892 (Emil Bieber)

Gustav Mahler in 1892 (Emil Bieber)

That life was dominated in 1888 by composing his mighty First Symphony, nicknamed the “Titan”, a work which was to herald the arrival of a new compositional force in music (though not well received at its premiere). Even as the Hero of the First Symphony was celebrated in music of epic scale, the composer began work on an equally vast symphonic movement which would announce that same Hero’s passing. Taking as its cue the Funeral March movement of Beethoven’s form-shredding “Eroica” Third Symphony, Mahler named his coruscating creation Totenfeier (Funeral Rite), in which a thinly veiled programmatic discourse in sonata form wrestles with the existential questions he outlined in the quotation above (taken from a letter the composer wrote in 1896 upon the completion of the Second Symphony).

In Totenfeier the Hero is struck down, and a ghoulish funeral procession unfolds. Intimations of a world beyond, a Paradise perhaps, occasionally intrude - but his descent into the vile corruption of the grave is inevitable and inexorable. He has passed into “The undiscovered country from whose bourn / No traveller returns” - now only a “quintessence of dust”.

As the composer wrote:

“While writing it, I had a vision of my corpse lying in a coffin, surrounded by funeral wreaths.” And later, “It is the hero of my D-major Symphony [the First Symphony, 1887] who is being borne to his grave, his life being reflected, as in a clear mirror, from an elevated vantage point. At the same time, it expresses the great question, ‘To what purpose have you lived? To what purpose have you suffered?’... We must know the answers to these questions if we are to continue living....”

Upon completion, Mahler realized that this self-contained Totenfeier - even as it closed the casket lid upon his Hero’s mortal remains, deeds and aspirations - demanded an answer to those questions. The musical questions had been asked - but not answered - in a symphonic movement as rigorous and forceful as any. Death might be final, but the glimpse of the Hereafter was presented in music of radiant harmonic and textural simplicity, music that would eventually return in the Finale to the Second Symphony composed many years later.

But at that time, in 1888, a continuation eluded the composer, so the work lay dormant. Besides, his conducting career was in the ascendant and massively time consuming. (He would come to set aside the summers at his mountain retreat as his time of most concentrated composition).

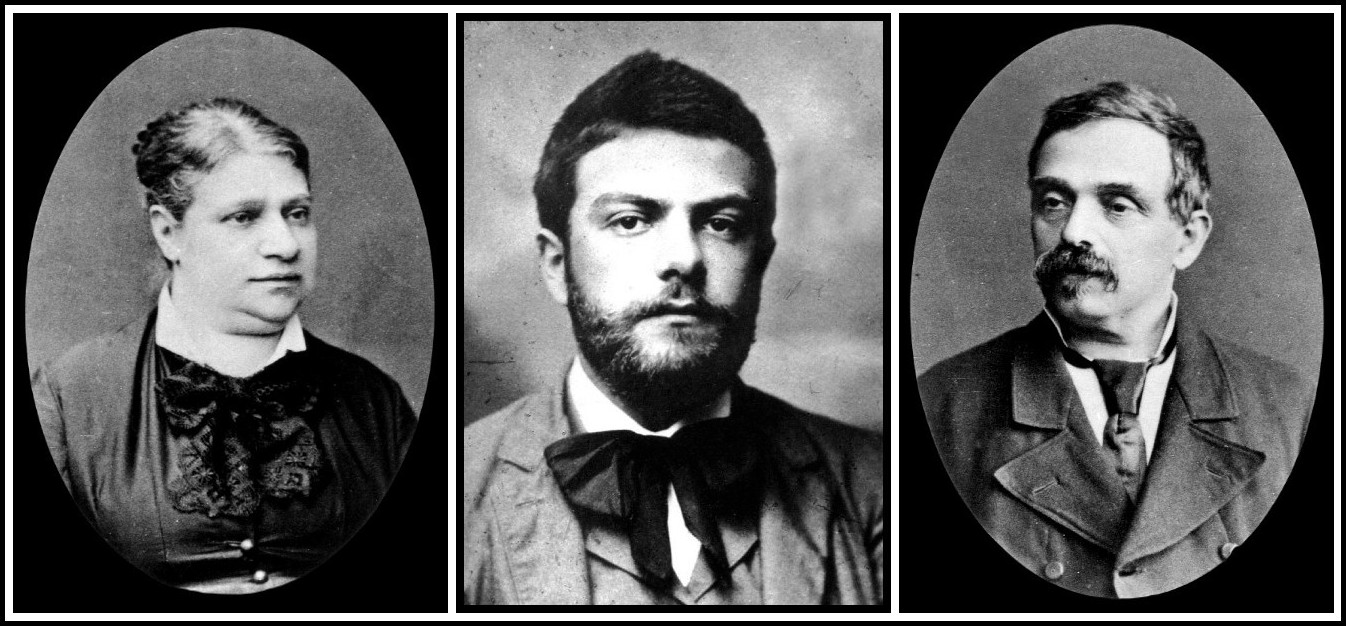

(from l. to r.) Mahler's mother Marie, brother Otto, and father Bernard

(from l. to r.) Mahler's mother Marie, brother Otto, and father Bernard

Death was much on the composer’s mind during those years of the Second’s composition. That time had seen the passing of his father, his mother, and sister Leopoldine within months of each other; in 1895, the year of the work’s debut, his brother Otto committed suicide; nine of his 13 siblings had died in infancy. No wonder he wrote of these matters again to his sister in 1901:

“What next?… What is life—and what is death? Have we any continuing existence? Is it all an empty dream, or has this life of ours, and our death, a meaning.”

Cast into his own 6-year compositional struggle to come up with a musical and philosophical answer to these questions, Mahler emerged finally in 1894 with the so-called “Resurrection” Symphony No. 2, whose first movement is that same Totenfeier, albeit with minor alterations.

I think it fair to say that of all Mahler’s symphonies, the Second is the most overtly dramatic - which is saying something! The progression from dark to light is as simple and linear as it is compelling, but the manner in which Mahler taps into our universal fear of death and desire to find hope and meaning beyond the grave grants this work its special appeal, and power. That, and the fact that to put it on you have to marshal huge forces: a vast orchestra, choir, soloists and - never one to be left out on such occasions - an organ. To paraphrase Douglas Adams when he was describing Space in The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy:

“[Mahler] is big. You just won't believe how vastly, hugely, mind-bogglingly big it is.”

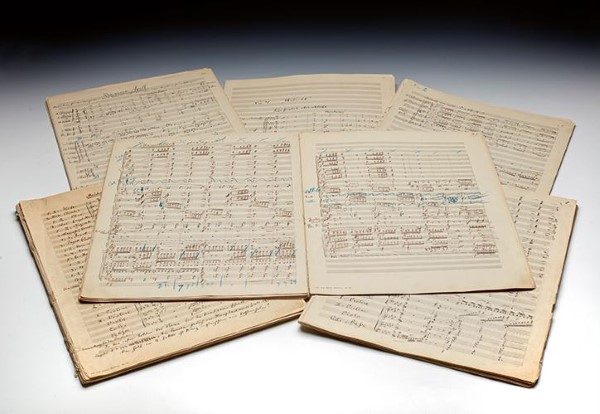

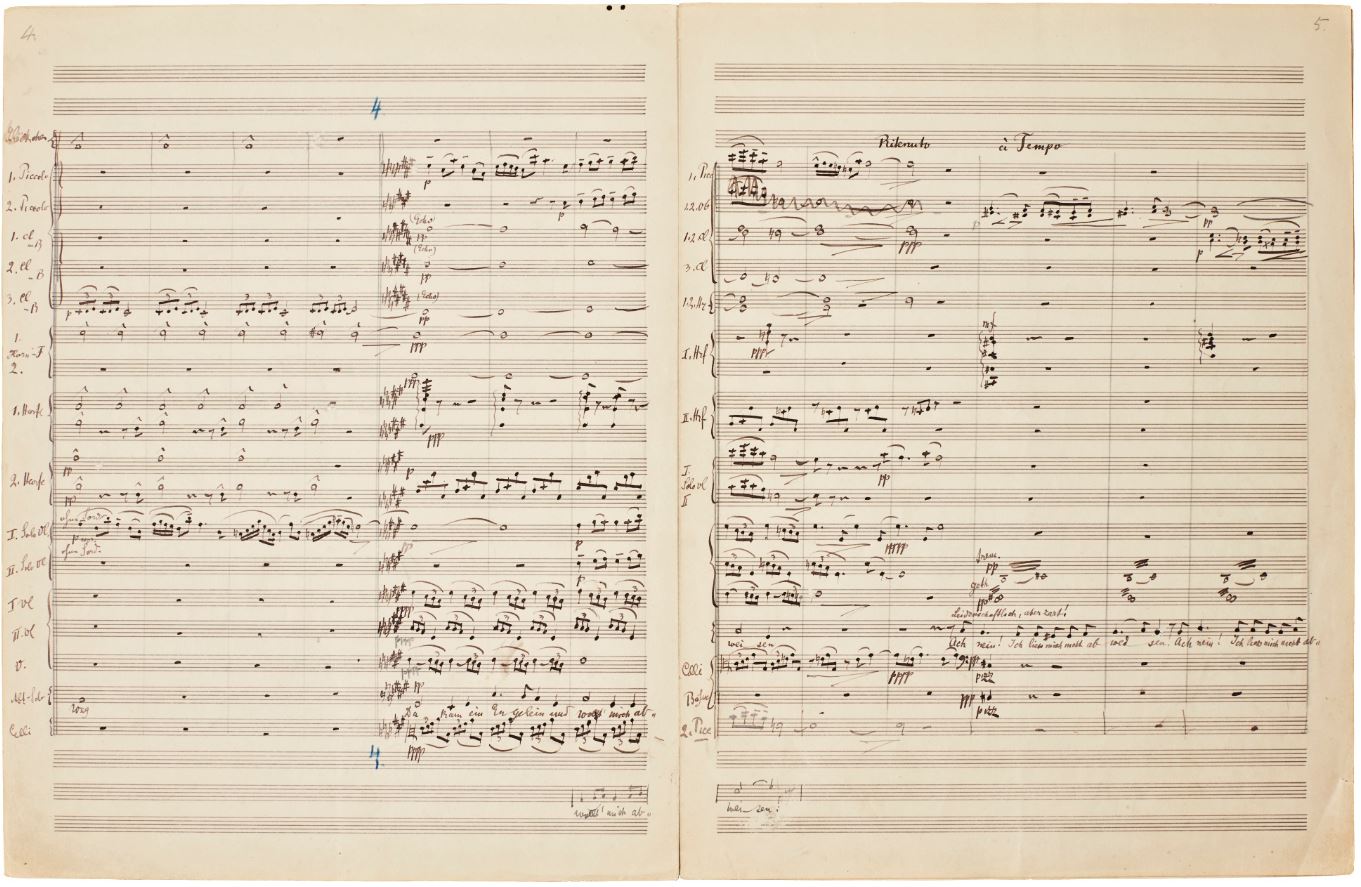

Original Autograph Score for Mahler's 2nd Symphony "Resurrection"

Original Autograph Score for Mahler's 2nd Symphony "Resurrection"

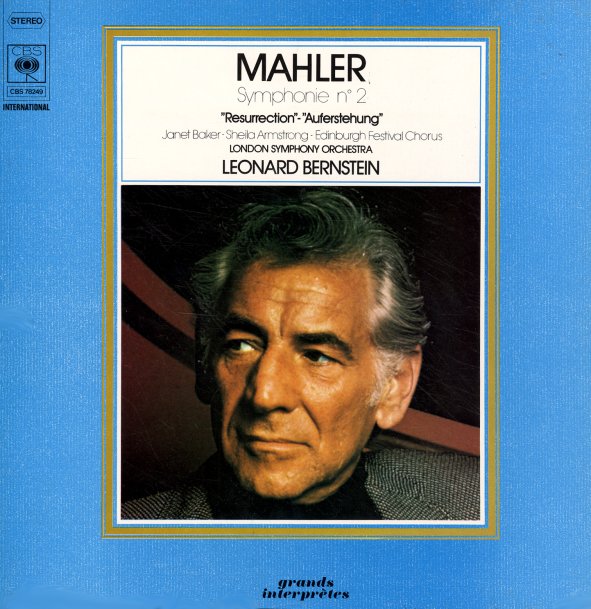

A musical spectacle, a concert Big Event that tells a gripping story of earthly struggle, of triumph over defeat, and concludes with an unequivocal statement and embrace of eternal joy beyond this mortal coil: these are the reasons that I think for many this work is an ideal entry point to the Mahlerian universe (and, yes, it is indeed a universe in terms of its scale and variety). It was my own gateway to the composer when as a mere lad of 13, I sat down in front of our black and white television set to watch a broadcast of Leonard Bernstein’s performance of the “Resurrection” in Ely Cathedral with the London Symphony Orchestra, soloists Janet Baker and Sheila Armstrong, and the Edinburgh Festival Chorus.

I was never the same again.

Mahler in Ely Cathedral - (from l. to r.) Janet Baker, Sheila Armstrong, Leonard Bernstein, LSO and Edinburgh Festival Chorus

Mahler in Ely Cathedral - (from l. to r.) Janet Baker, Sheila Armstrong, Leonard Bernstein, LSO and Edinburgh Festival Chorus

The combination of this incredibly dramatic music, unlike any I’d heard before, with the overtly emotional and demonstrative conducting of Bernstein - well, it simply blew me away.

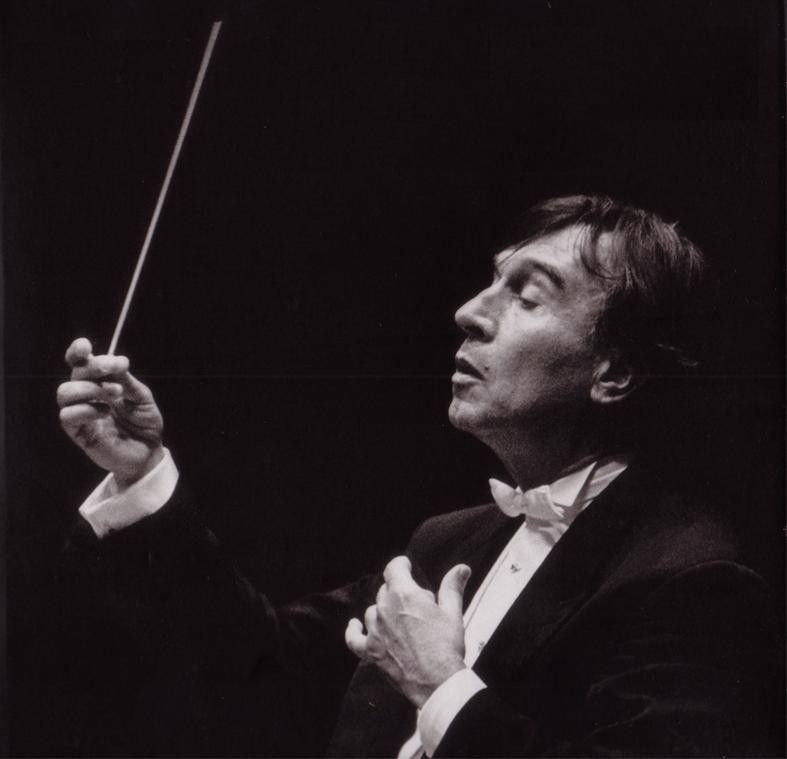

Leonard Bernstein conducting Mahler's "Resurrection" Symphony in Ely Cathedral

Leonard Bernstein conducting Mahler's "Resurrection" Symphony in Ely Cathedral

This is such a Ground Zero moment in the explosion of Bernstein’s own nuclear talent, a definitional piece of footage, that Bradley Cooper chose it as the centerpiece recreation for his portrayal of the musician in his film Maestro (2023).

Remember also that this 1973 filmed performance (not live - though it just as well could be for its sense of spontaneity and edge-of-your-seat excitement) came just as interest in Mahler’s music was growing in earnest, and itself acted as a huge stimulus to the Mahler revival. Hard to believe today that back then his music was rarely programmed or recorded - now it dominates concert schedules and the classical catalogue.

For all the technical challenges inherent in recording a work like the Second Symphony within the resplendently reverberant acoustic of Ely Cathedral, and the resulting sonic imperfections, that set of records, released by CBS, remains the rendering of the “Resurrection” by which I judge all others, even Bernstein’s two other official recordings, for CBS in 1964, and for Deutsche Grammophon in 1988 - which are equally but differently compelling, and more sonically uniform. There’s just something about the Ely Cathedral performance - catching lightning in a bottle.

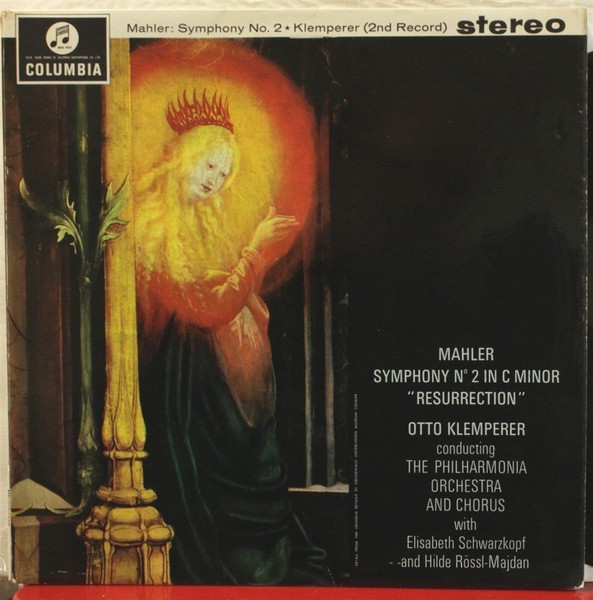

The fact that my record and CD shelves groan under the weight of assorted recordings of this work and the rest of the Mahler cycle by multiple conductors and ensembles is testament to my enduring fascination with this composer (in this I am not alone). But it also testifies to the fact that the “Resurrection” Symphony remains elusive on record in terms of naming a definitive recording. Yes, the three Bernstein recordings remain, for me and many, foundational and lodestars (to which I would add Klemperer on EMI/Columbia in 1963), but I wouldn’t say any of them were THE benchmark. Any benchmark recording has to not only catch all the many conflicting inner impulses and external affects and effects of this many-faceted work, it needs to do so within a recording that can not only capture the smallest details, convey every second of an intense dramatic narrative, but also open up to accommodate the vast orchestral and choral forces that literally rend the heavens asunder in the finale.

It’s a tall order, and I have yet to hear a version on record or disc that achieves all those things to the nth degree. Maybe I never will - the Second is that kind of a work.

Claudio Abbado

Claudio Abbado

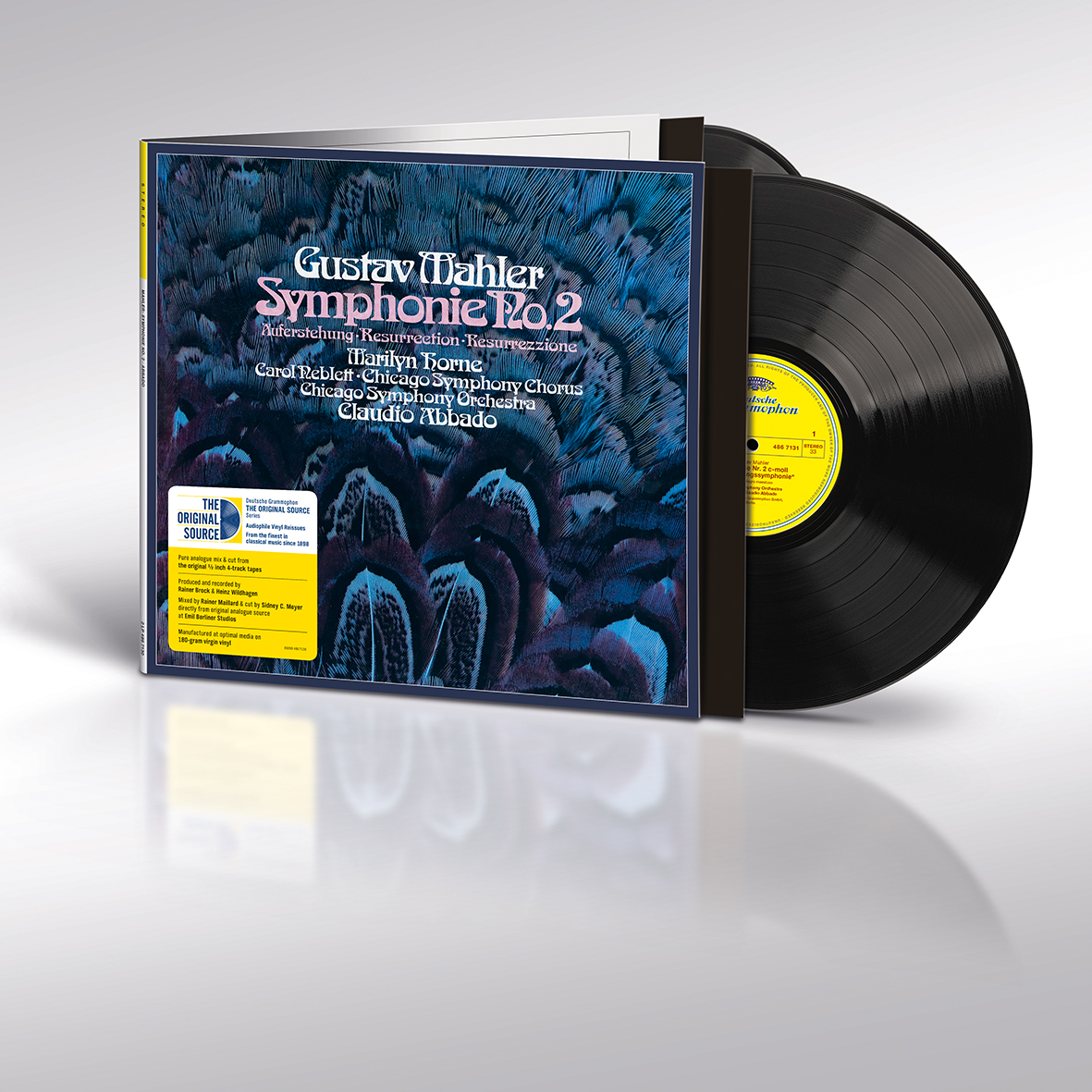

I say all this by way of setting the scene for what I will be writing about Claudio Abbado’s attack on this particular summit of the symphonic repertoire. Like every other serious contender for benchmark that I have heard, some of it works very well indeed, and some of it just misses by the smallest of margins - not in any way that will impede your enjoyment of what is definitely one of the better accounts out there, but in a way that will have any seasoned listener of the work thinking about other versions that capture a particular moment in the score more compellingly. This is not always a matter of performance either. The engineering here is top-notch, and the Original Source refresh by the wizards of Emil Berliner Studio, Rainer Maillard and Sidney C. Meyer, is as good as any in the series. However, as with a few other releases in this series, there are moments when the very clarity and transparency of mastering directly AAA from the original 4-track masters has revealed some of the shortcomings of the original engineering. And for me those shortcomings relate mainly to the interaction between the performers and the acoustical space in which they have been captured, and how it affects the impact of the music differently in different sections: sometimes very positively (as in the radiant peroration), sometimes a little negatively in the sections that need to present layered differentiation between instruments and sections without losing impact. The large acoustic occasionally mitigates against the achievement of a truly audiophile level of fidelity.

Unlike the recent Abbado/Prokofiev detonation I gave a rave review to, this Mahler was not taped in Chicago’s Symphony Hall, but rather in Medinah Temple, a somewhat larger venue.

Stokowski recording in Chicago's Medinah Temple in 1968

Stokowski recording in Chicago's Medinah Temple in 1968

You will immediately hear the difference at the very opening of the first movement, with its attaca upper string tremolos, joined by the fierce basses and lower wind (which, hurrah, you can actually hear through those grinding ‘cellos and double basses). We are in a very large space indeed, and for all the precision and energy of the Chicago players, some of the impact is lost by virtue of the acoustic.

Solti recording The Flying Dutchman in Medinah Temple in 1976

Solti recording The Flying Dutchman in Medinah Temple in 1976

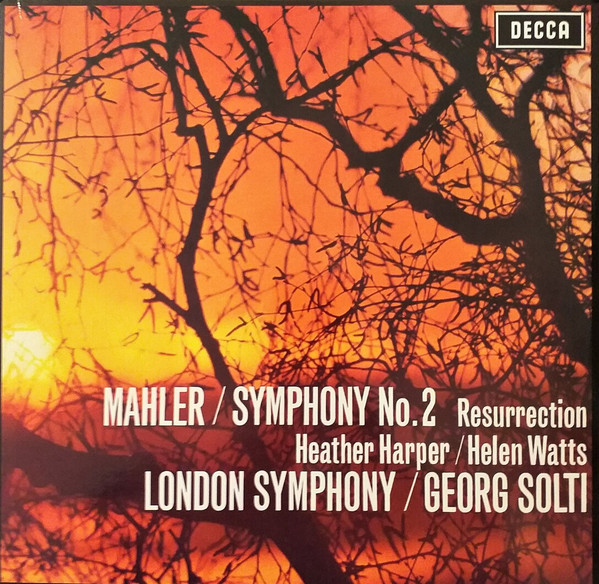

For me, this first movement, and this opening thematic material (which recurs throughout) remains the foundational test for the whole work. The range of ways in which different recordings present this opening salvo is enormous: some fast, some slow; some highly articulated, some looser. Abbado falls somewhere in the middle: he’s fierce but fast, which means that some of the impact is lost in the large hall. If this had been recorded in the same acoustic as the Prokofiev the impact and effect would be the polar opposite - it would sizzle in stark close-up, more in the manner of Solti’s classic account on Decca with the London Symphony Orchestra in 1966, long an audiophile favorite but extremely hard-driven in that Solti way, which sometimes precludes the fullest sense of repose and mysticism that are also an essential part of any interpretation. (But it should be in any Mahler fan’s library - either as an OG or the fine Speaker’s Corner reissue).

But when we move into the blissful second subject, a foreshadowing of the heavenly transcendence of the Finale, the larger acoustic works to Abbado’s advantage, bathing the music in a glow of calm peace and bliss. Quite magical.

Cards on table. This opening movement is one of my favorite Mahler creations. The drama of it, the huge contrasts, the compelling musical argument railing at the inexorability of Death: it’s gripping stuff. Does Abbado nail it? Not quite. But who does?

I always come back to Bernstein. Interesting to compare his version recorded in Ely Cathedral, whose vast acoustic makes that for Abbado sound like an isolation booth in comparison. The miking is close indeed, so you get all the detail, but then you also have the cathedral reverb piling back in. There is little sense of the acoustical integration you get with Abbado (for all its shortcomings), but the ear adjusts to the experience, and then one is left to focus on the drama that unfolds unerringly. The coolness of Abbado in comparison (which many will prefer - an important point to make) is self-evident. And it isn’t that Bernstein is imposing drama on the piece (as his detractors love to claim), it’s that he is finding more of the drama buried in the score, and bringing it out into the foreground, but NEVER at the cost of the purely musical argument.

This isn’t to say that Abbado isn’t dramatic - he is. But with Bernstein you are locked into an intense psychodrama that has your palms sweating. As the movement progresses into its “breakdown”, where all hell breaks loose leading into massive grinding chords (the final blows of death and oblivion perhaps?) that take us back into the movement’s opening thematic material in the recapitulation (Mahler works within strict sonata form here), Bernstein clutches at your heart, clawing at your mortality, making you share in the composer’s pathological fear of the Grim Reaper. Abbado gets very close to this, but he lacks that final ounce of Bernstein’s all-in commitment. Conducting Mahler for Bernstein is always a matter of life and death. In this work especially, I think that’s what’s called for. But again, many will prefer Abbado’s slightly more moderated approach.

Recording-wise, this first movement was where I most felt like the engineering was finding its feet. The shifts in perspective - for example violins being sometimes less “present” than they are at others - were most apparent here. You can sense how in mixing to just 4 tracks (as opposed to 8, which would have definitely facilitated a more consistent orchestral balance and soundstage on both the original and OSS mix) the engineers are constantly making slight adjustments so that, for example, the brass don’t blow out the rest of the orchestra in the louder sections. Compare this to the Abbado/Prokofiev release, where all the sections of the orchestra remain consistently placed within a detailed soundstage, no matter how loud or soft. Everything in proportion, all the time. In the Mahler, there are constant small shifts of emphasis and spatial position which are less organic, but done no doubt to try and accommodate not only the radical changes in dynamics, but also the challenges of the large acoustic. However, one thing I will say: the detail revealed in the remastering means that none of the scoring is lost as it often is in more traditional set-ups that do not include ambient hall information. All the Mahler is there all the time, and that is noteworthy for a score of this complexity. This is down both to Abbado’s close attention to the score and the engineers’ skill.

Everything settles down for the next two movements, and these are overall more successful in terms of both consistency of performance and sound.

In his original score, the composer gave a most unusual instruction: that there should be a pause of five minutes after the first movement. You are unlikely to find this adhered to strictly in the concert hall, but it speaks to the composer’s sense of the self-contained finality of the first movement.

In 1903 Mahler wrote to conductor Julius Buths:

“...there must also be a long, complete rest after the first movement since the second movement is not in the nature of a contrasting section but sounds completely incongruous after the first… This is my fault and it isn’t lack of understanding on the part of the audience.... The Andante is composed as a sort of intermezzo (like an echo of long past days from the life of him whom we carried to the grave in the first movement – ‘while the sun still smiled at him’)… While the first, third, fourth, and fifth movements are related in theme and mood content, the second is independent, and in a sense interrupts the stern, relentless course of events.”

Abbado has the full measure of the gentle, lilting charm of this respite, and the recording here is a perfect match for him and his players: relaxed, buoyant, open. We are entering the world of mountain pastures in summer, the rural landscapes so beloved of the composer, and which he was to evoke so beautifully throughout his music as a counterpoint to earthly struggle, human suffering, and the inevitable hammer-blows of Fate and, ultimately, Death. Shades and shadows of those darker vales intrude several times throughout this movement, only to subside. Death, glimpsed out of the corner of our eye, walks by our side always.

The third movement emerges as a darker doppelganger to the second, using the traditionally lighter mode of a waltz while also hinting at more demented undercurrents: “The Blue Danube” played on the fiddle by the Devil perhaps? (A similar pairing of mirror-image movements occurs in the 6th Symphony’s First and Second movements, if they are performed in the order I and many prefer, and as presented on Karajan’s recently reissued recording, one of the Original Source essentials). The music is based on an earlier song setting by Mahler from “Das Knaben Wunderhorn” or “The Boy’s Magic Horn”.

I cannot better Richard Osborne’s description of this movement in his superb sleeve note, reproduced from the original release in full for this reissue:

“For Mahler, it was full of disgust, disbelief and the spirit of negation; Bruno Walter found it ‘nocturnal and spectral’. And yet the Knaben Wunderhorn story is engaging enough: St. Antoni preaching to attentive but unrepentant fishes (the piccolo gives out the homily). Like men, they listen but take no heed: the pikes remain thieves, the eels great lovers; the crab still goes backwards, the carps guzzle, and the cod stays fat. In practice, it is a pure Mahler mixture of innocence and irony, sweet and sour, colors glowingly blended, until the storm-clouds gather and the world erupts into nightmare - a nightmare which destructs the third movement and launches the finale.”

Abbado captures all this perfectly but perhaps a little neatly, though the listener is afforded many opportunities to hear soloists within the orchestra shine. For a more Breughel-esque vision of grotesquerie and disruption you will have to turn to Bernstein, as always pointing up the layers and depths, tweaking the moments without disrupting the overall musical flow and argument.

Autograph Manuscript for "Urlicht"

Autograph Manuscript for "Urlicht"

And now we have Mahler’s masterstroke, a coup de théâtre that rarely fails to make the heart stop. Seemingly out of nowhere, and out of the silence, the mezzo soprano soloist intones the opening notes of Urlicht (Primordial Light) set to words from “Das knaben Wunderhorn”

O red rose,

Man lies in direst need,

Man lies in direst pain,

I would rather be in heaven.

I then came upon a broad path,

An angel came and sought to turn me back,

Ah no! I refused to be turned away.

I am from God and to God I will return,

Dear God will give me a light,

Will light my way to eternal blessed life.

The musical tone shifts to one of serenity and restraint, hymnal chords shot through with instrumental flourishes suggestive of childlike wonder. Here soloist Marilyn Horne and Abbado are transcendent, aided by the wide open recording and the seemingly infinite headroom afforded the human voice by the Original Source remastering. (I cannot think of any other records that so effortlessly capture the full range and color of the classical vocalist - this is why we need some opera, please DG). The heart does indeed stop.

Marilyn Horne

Marilyn Horne

And so to the Finale, which afforded the composer so much trouble.

Osborne again:

“Of the surging, vulgar march which dominates the finale’s first part, Mahler wrote: ‘The earth quakes, the graves burst open, the dead arise and stream on in endless procession. The great and little ones of the earth - kings and beggars, righteous and godless - all press on.’ ”

This is a truly demonic musical vision, and Abbado and the DG engineers rise to the task. Your listening room will shake and tremble suitably. It’s only when you switch to Bernstein that you will feel like your immortal soul is in peril.

At this point Mahler was confronted with the problem of how to face down this riveting drama of the End of Days that he had created so vividly. How would he articulate a vision of hope after all this “negativity” - to use a currently in vogue expression?

A solution sprang from the most unlikely of events.

He wrote in a letter to a music critic in 1897, recalling the events that led to his finding a way to finish the work:

“With the finale of the Second Symphony, I ransacked world literature, including the Bible, to find the liberating word, and finally I was compelled myself to bestow words on my feelings and thoughts…

“The way in which I received the inspiration for this is deeply characteristic of the essence of artistic creation. For a long time I had been thinking of introducing the chorus in the last movement and only my concern that it might be taken for a superficial imitation of Beethoven made me procrastinate again and again. About this time Bülow [storied conductor Hans von Bülow] died, and I was present at his funeral. The mood in which I sat there, thinking of the departed, was precisely in the spirit of the work I had been carrying around within myself at that time. Then the choir, up in the organ loft, intoned the Klopstock [German poet and playwright Friedrich Gottlieb Klopstock] ‘Resurrection’ chorale. Like a flash of lighting it struck me, and everything became clear and articulate in my mind. The creative artist waits for just such a lightning flash, his ‘holy annunciation.’ What I then experienced had now to be expressed in sound. And yet, if I had not already borne the work within me, how could I have had that experience?”

Hans von Bülow (1830 - 1894): doyen of 19th century conductors, a great supporter of Brahms and Wagner (even though the latter made off with Bülow's wife, Cosima, daughter of Franz Liszt). He conducted the premiere performance of Wagner's Ring cycle at Bayreuth in 1876, but remained immune to the charms of Mahler's music.

Hans von Bülow (1830 - 1894): doyen of 19th century conductors, a great supporter of Brahms and Wagner (even though the latter made off with Bülow's wife, Cosima, daughter of Franz Liszt). He conducted the premiere performance of Wagner's Ring cycle at Bayreuth in 1876, but remained immune to the charms of Mahler's music.

A great irony lay in the fact that it was at von Bülow’s funeral that inspiration struck: Bülow had long denigrated Mahler’s music and denied him the important imprimatur of his support (and therefore high profile performances). (In his sleeve note Osborne covers the details of their relationship in delicious detail). Mahler had actually played the conductor a piano reduction of his original Totenfeier movement, during which Bülow held his hands over his ears, finally bursting out: “If this is music, then I no longer understand anything about music.”

Mahler's "Composing Cottage" at Steinbach, visible at water's edge, lower right

Mahler's "Composing Cottage" at Steinbach, visible at water's edge, lower right

So, inspiration having struck, in the summer of 1894 Mahler returned to his newly constructed lakeside cabin at Steinbach to complete the symphony, supplementing Klopstock’s “Resurrection Ode” with some additional words of his own.

The Interior of Mahler's "Composing Cottage" at Steinbach

The Interior of Mahler's "Composing Cottage" at Steinbach

After the nightmare of the End of Days, the chorus enters pianissimo, like a whisper over the grave:

Arise, yes, you will arise from the dead,

My dust, after a short rest!

Eternal life!

Will be given you by Him who called you.

It’s another spellbinding moment. This is when Abbado’s performance and his engineers truly show their mettle, and there is nothing lacking in this Original Source remastering (except I did find myself inching up the volume level for this final side 4).

Magical moments abound, like when the soprano soloist Carol Neblett almost imperceptibly joins the choral sopranos, a detail often lost or over-emphasized in other recordings. Here it is judged to perfection and is heart stopping.

Carol Neblett

Carol Neblett

Offstage effects are rendered beautifully throughout. The Chicago Symphony Chorus, meticulously prepared by the legendary Margaret Hillis, rise magnificently to the occasion.

Margaret Hillis, Chorus Master of the Chicago Symphony Chorus, shouting instructions during sessions for The Flying Dutchman in 1976

Margaret Hillis, Chorus Master of the Chicago Symphony Chorus, shouting instructions during sessions for The Flying Dutchman in 1976

Throughout this section Mahler keeps the forward impetus going, the range and variety of orchestral and choral writing plentiful. He is always the dramatist, with a superb sense of pacing, as he leads up to his Big Finish.

I can offer up no better description of this music than that to be found in a passage from Coleridge’s Rime of the Ancient Mariner:

Around, around, flew each sweet sound,

Then darted to the Sun;

Slowly the sounds came back again,

Now mixed, now one by one.

Sometimes a-dropping from the sky

I heard the sky-lark sing;

Sometimes all little birds that are,

How they seemed to fill the sea and air

With their sweet jargoning!

And now 'twas like all instruments,

Now like a lonely flute;

And now it is an angel's song,

That makes the heavens be mute.

No one builds a vast symphonic and choral climax like Mahler, and the “Resurrection” triumph eclipses all others. (I will confess to being no particular fan of the even more massive 8th, the so-called “Symphony of a Thousand” - I await, like Saul of Tarsus, conversion on my own Mahlerian road to Damascus). All it needs is for the organ to come rumbling in during the final pages for this immaculate Original Source remastering and pressing to rend the sky and let that shaft of sunlight bathe the listener in a heavenly light. And boy do the Chicago players like to turn on the shower of orchestral rain at full blast!

The chorus rings out with these words, Mahler’s own:

O Sorrow, all-penetrating!

I have been wrested away from you!

O Death, all-conquering!

Now you are conquered!

With wings that I won

In the passionate strivings of love

I shall mount

To the light to which no sight has penetrated.

I shall die, so as to live!Arise, yes, you will arise from the dead,

My heart, in an instant!

What you have conquered

Will bear you to God.

You will reach the end of these records transformed. But, it has to be said, to be transfigured - for that you will have to turn to Bernstein in any one of his three recordings, even though none of them sonically match the best moments in this Abbado.

"Lenny" taking flight during the climactic final movement of Mahler's 2nd Symphony in Ely Cathedral

"Lenny" taking flight during the climactic final movement of Mahler's 2nd Symphony in Ely Cathedral

For the LSO/Ely Cathedral rendering, seek out the 1974 German pressing. (I urge anyone interested in this unique recorded document to read this fascinating background article, and to watch the complete film of the occasion).

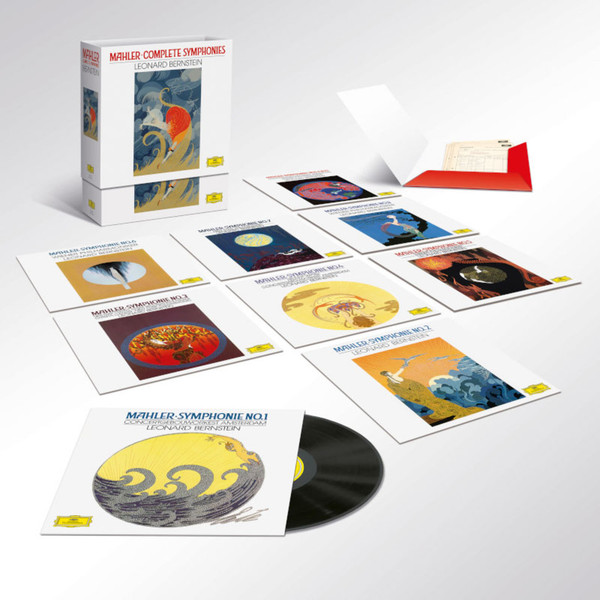

For the 60s CBS/Sony, turn to either the most recently remastered (from files) version in the massive vinyl box set or same on CD.

For the DG you have to go likewise for the EBS remastered complete set on vinyl, reviewed here by my colleague Michael Johnson. I would not want to be without all three.

Hard-core Mahlerians (and even those just dipping their toes into these waters) will also not want to be without Klemperer’s classic 1963 EMI account - and any number of other favorites, old and new. (Anyone who owns the Electric Record Company’s expensive reissue of the Klemperer please feel free to send me their copy for a permanent - I mean “extended” - loan…)

My copy of the Abbado was immaculate, with no ticks or pops or unwanted bumps; the presentation featuring the usual audiophile catnip of photos of original session documentation. The only black mark here is not including an insert of the texts and translations - an unnecessary economy and annoying omission which I hope will not be repeated on any future vocal or choral or (dare we hope) operatic OSS reissues. We classical record buyers like to have all necessary documentation included for the full retro experience (even if same texts are readily accessible online).

Like I said at the beginning of this review (now approaching its own Mahlerian lengths), I cannot honestly say any one recording of the “Resurrection” Symphony earns the coveted 10/10 rating (representing Top Marks for Sound and Music - 11/11 is reserved for those few that are truly extraordinary), so the 9/9 rating here should not deter anyone from exploring one of the most thrilling and compelling works in the classical canon. It’s a work that is almost impossible to accommodate within a home audio setting, but this release gets as close as any, and in more than a few places approaches musical and sonic nirvana - just the way Mahler would have wanted it.

More please!

Limited edition of 3700 copies.

Available for purchase at the DG shop, and stateside at Acoustic Sounds and Elusive Disc.

.png)