Battle of the Sonic Blockbusters - The Original Source Goes Nuclear

Prokofiev with Abbado vs. Reiner Living Stereo vs. Dorati Mercury Living Presence… Who wins?

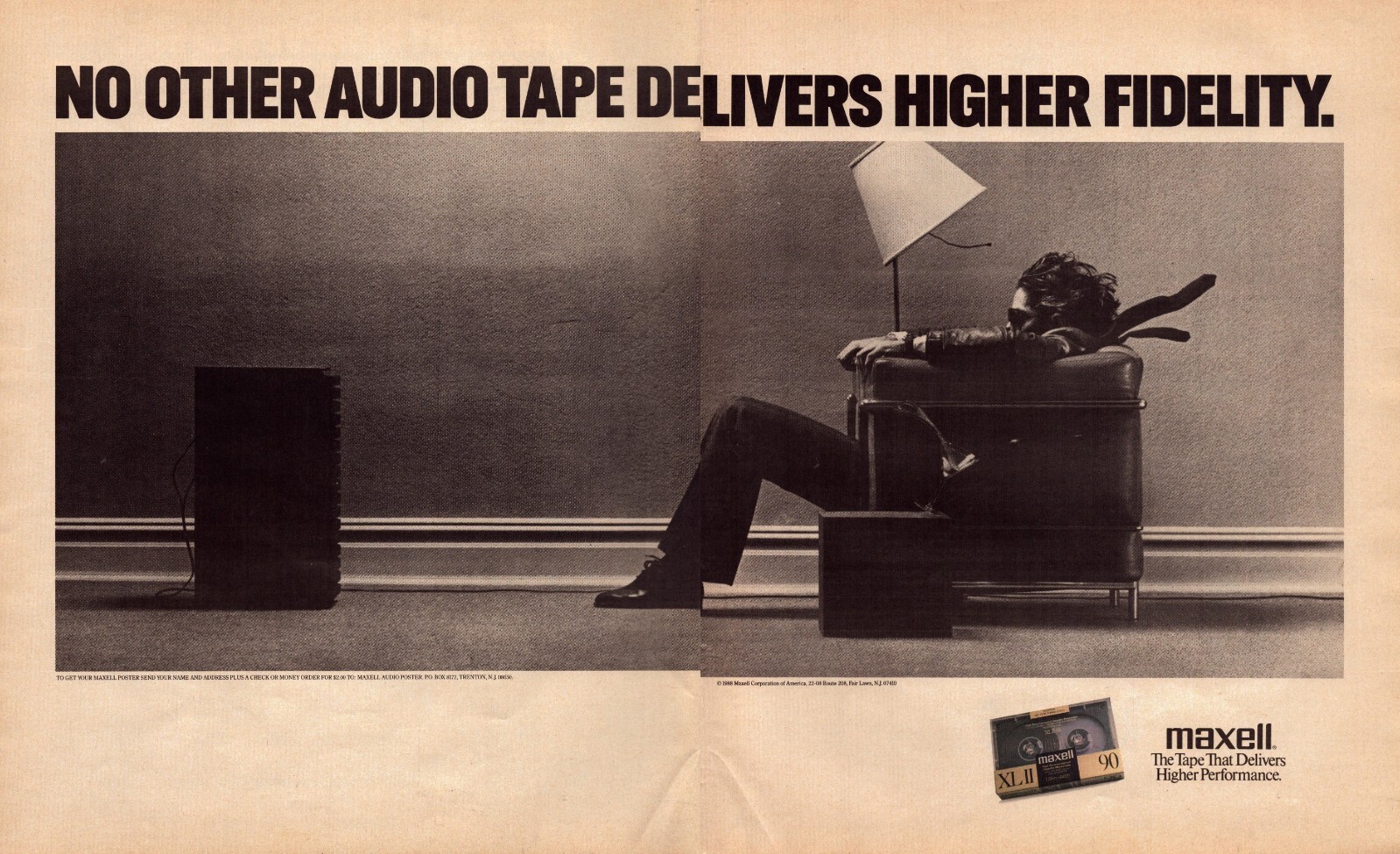

I remember buying this record when it first came out. It immediately shot to the top of my list of orchestral Big Bang records that I would pull out when I wanted to be pinned to the back of my listening chair, like the guy in those famous Maxell cassette tape commercials.

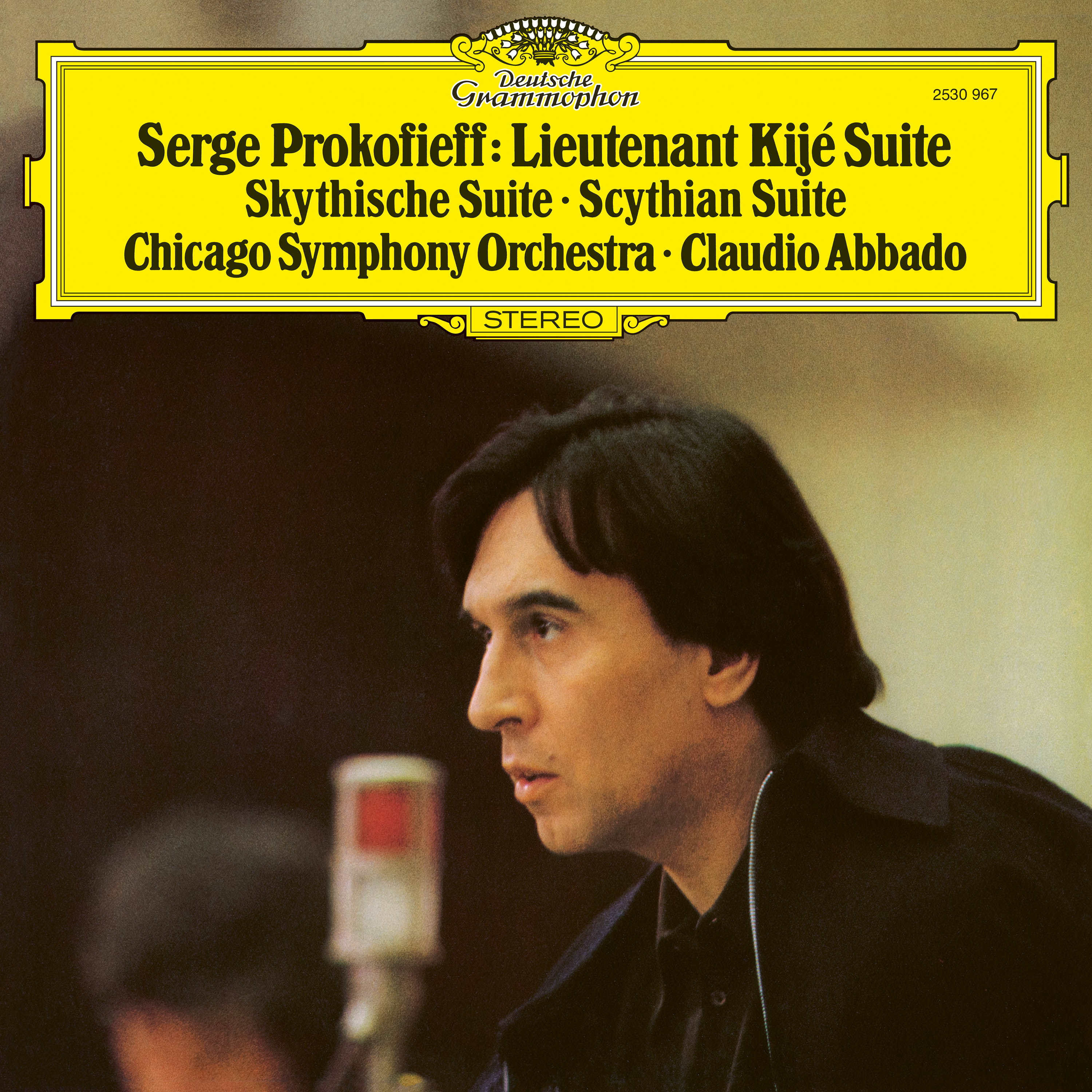

Surprisingly for a 70s DG record, this Abbado outing with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra has remained an audiophile favorite, despite being a DG LP with all their attendant shortcomings of the period. The performances were always rightly lauded, with special mention being made of the unleashed Chicago brass being given full license by Prokofiev’s searing scores and Abbado’s direction to do their considerable thing to the max. So when I heard this record was going to get the Original Source makeover, I couldn’t wait to drop the needle on this musical thunderstorm.

In all honesty, it’s really Side 1 - the Scythian Suite - where the music gets real hairy, though Lieutenant Kijé has its unbridled moments too. When it comes to musical barbarism, Prokofiev outruns even Stravinsky and Bartok in the Loud and Savage Sweepstakes!

But Prokofiev also has his aching romantic side, and he is able to express it in music that is every bit as searing as his more violent outbursts. It’s no surprise that his ballet score for Romeo and Juliet remains one of the most passionate musical utterances of all time. So there are moments of music in both these works which will seriously pull on your heartstrings. And boy can old Serge write a great tune - the catchy melody of Kijé’s “Troika” movement is an ear worm you will struggle to remove for, basically, forever.

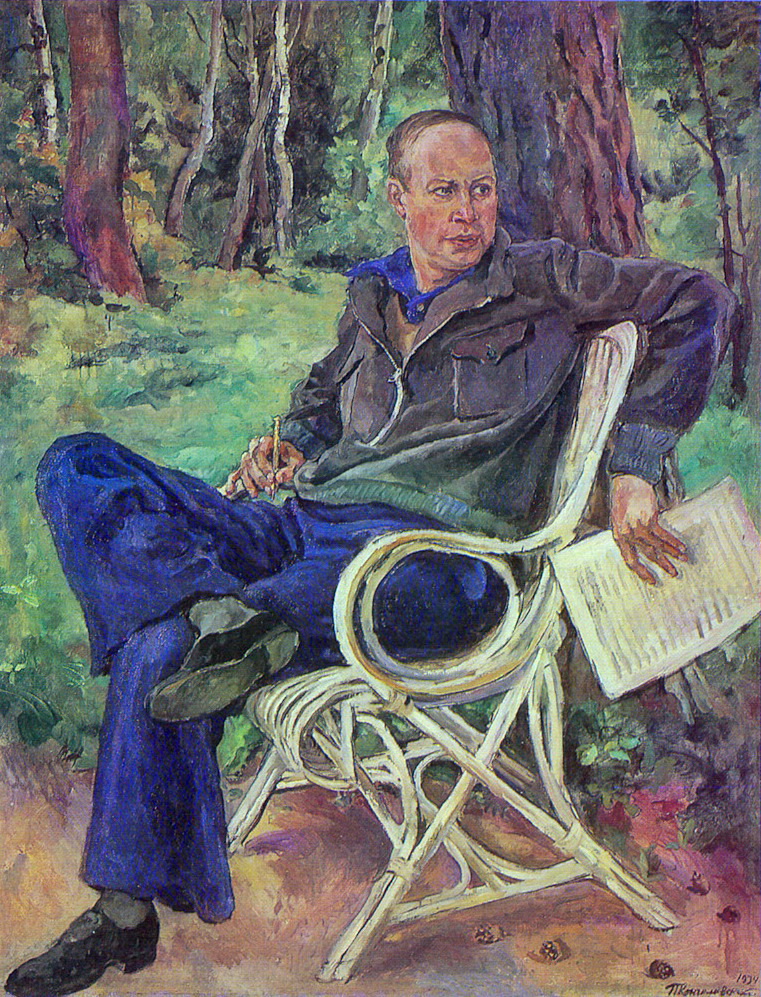

Serge Prokofiev (1891 - 1953)

Serge Prokofiev (1891 - 1953)

Serge Prokofiev was, like the slightly older Stravinsky, the bad boy of Russian music in the early 20th century. His youthful works were marked by glaring dissonance and rhythmic aggression, and no where is this more exemplified than in his first major orchestral work, the Scythian Suite (1915). This was drawn from a ballet score titled Ala and Lolly Prokofiev had written on commission from Diaghilev’s Ballet Russes, but which had been rejected for various reasons.

(from l. to r.) Conductor Ernest Ansermet, Diaghilev, Stravinsky and Prokofiev

(from l. to r.) Conductor Ernest Ansermet, Diaghilev, Stravinsky and Prokofiev

Like Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring, Prokofiev had drawn on a primitivist, prehistoric scenario from Slavic mythology which allowed the composer to give full rein to his modernist idiom. The ballet essentially charted the battle between darkness and light. Light was personified by the sun God, Veles. Ala was the nymph of the forests imprisoned by the monster Chuzbog, a character not dissimilar to the evil Katschei in Stravinsky’s The Firebird. Coming to her rescue was the brave Scythian warrior Lolli.

The resulting Scythian Suite runs the range from the spectacularly loud and brash opening “Adoration of the Sun God Veles and Ala” and the subsequent “Le Dieu ennemi at la danse des esprits noirs” (Orgy for the Bad Guys), to the more beguiling depiction of magical night (anticipating Bartok’s own numerous “night music” concoctions), and the final movement’s resplendent victory of light over darkness which nevertheless retains that irresistible Prokofiev “spiciness”.

The first performance of the Scythian Suite at the Maryinsky Theatre in St. Petersburg in January 1916 was, like, The Rite of Spring, a succés de scandale (even if it avoided the riot that overtook Stravinsky’s premiere). Some were delighted, others appalled.

Prokofiev reported on the evening’s events:

“The timpanist tore the kettledrum head with his furious blows, and Siloti [the impresario, a noted pianist-composer himself] promised to send me the mangled piece of leather as a keepsake. In the orchestra itself there were noticeable signs of antagonism. ‘I have a sick wife and three children, must I be forced to suffer this hell?,’ grumbled a cellist, while behind him the trombones blew fearful chords into his ear. Siloti, in fine fettle, said we had given the audience a right slap in the face.”

“A scandal in high society,” reported the critic of the magazine Music. “The first movement was received in silence. The last called forth both applause and stormy protests. Despite this, the composer, who had conducted his own ‘barbaric’ work, took a number of bows.”

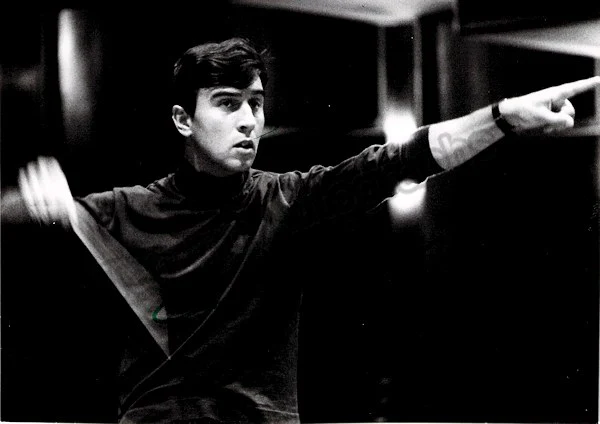

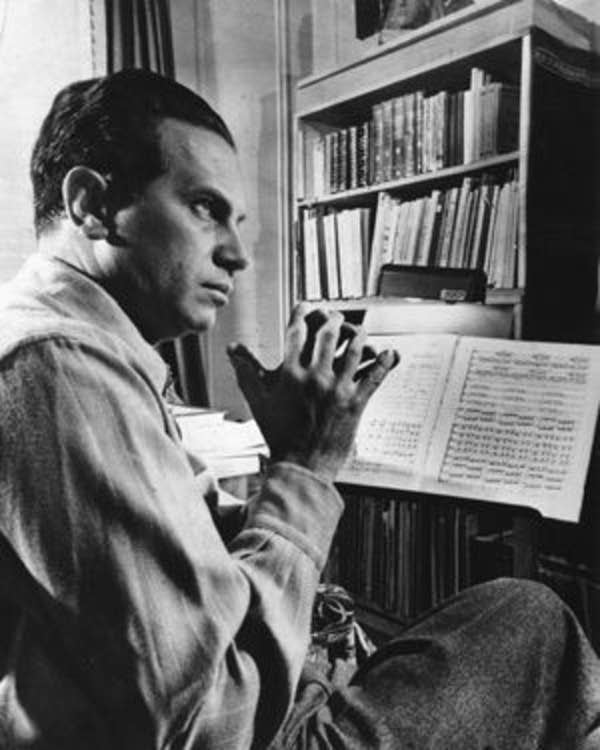

Claudio Abbado

Claudio Abbado

Needless to say, Claudio Abbado - a noted conductor of Prokofiev since his earliest days (seek out his Decca recordings of ballet music from Chout and Romeo and Juliet, and of the 1st and 3rd Symphonies) - lays into Prokofiev’s thrilling score with a vengeance, and the Chicago players are with him all the way. That opening paean to the Sun God will rip the grilles off your speakers if you have them - it is massive. The Original Source series has already had occasion to bring you the famed Chicago brass section of this period in widescreen technicolor in Barenboim’s traversal of Bruckner’s 4th Symphony, and here those bad boys are even more unfettered. Oh my lord what a thrilling to-do we have here, which only gets even more down and dirty in the second movement’s Evil Orgy. Those pile driving opening chords will shake your windows (and provided a musical template for future Hollywood film composers depicting savage American Indian attacks in Westerns). Percussion (especially xylophone) has a field day, and Prokofiev does some really cool stuff with string harmonics!

But then we have the exquisite cadences of the third movement’s depiction of Night, replete with enthralling melodies and delicate instrumental flourishes with pre-echoes of the Balcony scene in Prokofiev’s ballet Romeo and Juliet. A tinge of the Oriental gives the piece a lovely sense of exotica. But the sense of menace remains with deep brass and low percussion occasionally intruding. Couldn’t be more different from those first two steamroller movements. It’s all utterly beguiling. Finally the threat of the Evil God remerges full-force with the return of that pile-driving motif, only to be overwhelmed by the night again.

The final movement depicts Ala’s rescue, all Hollywood daring-do (no wonder Prokofiev would become such a great film composer). In victory Prokofiev indulges in some of his most inventive orchestrations and out of left-field melodies and harmonies. I find something quite heart-stopping in Prokofiev’s unpredictable manner, common to all his works - the reason why he is one of my absolute favorite composers and continues to reveal new facets with each fresh listen. He just constantly surprises you, no matter how many times you hear the same piece.

The final apotheosis of the Sun God is truly resplendent and massive, the orchestra giving its all. Your system will (hopefully) sparkle and tremble in awe.

Take a breather after all that - maybe pour yourself another glass of wine - before flipping the platter for Side 2’s Lieutenant Kijé, one of the composer’s most popular works.

LIEUTENANT KIJÉ

A Still from Lieutenant Kijé (1934)

A Still from Lieutenant Kijé (1934)

After spending many years abroad after the Revolution, predominantly in New York and Paris, Prokofiev determined to return to the now Soviet Union, which he did permanently in 1936. His eyes were completely open as to the potential political challenges he might face, but these were overridden by his belief that his career would be better served in his homeland. He had initially made his mark as a formidable concert pianist, and throughout his life fell back on concertizing to subsidize his composition. (It’s also why he wrote so many fine solo and concerto piano works).

His compositional style had moved towards a more accessible, simpler idiom - a prerequisite for any Soviet composer of the day. In the years leading up to his permanent return, Prokofiev still went back for shorter periods of time to perform. When the possibility of writing the music for a satirical film arose in 1933, one of the first Soviet “talkies”, the composer jumped at the opportunity to be involved in an officially approved project that he felt could help smooth his way back into the country.

Lieutenant Kijé - Film Poster

Lieutenant Kijé - Film Poster

Lieutenant Kijé tells the story of a fictitious character invented by courtiers to avoid the wrath of the Tsar. They create for Kijé an entire life, and then kill him off when he has served his purpose.

The film was a great success, and Prokofiev extracted from it a five movement suite for the concert hall, modifying the orchestration in the process (like adding the pungent saxophone to embody Kijé himself). You will immediately hear how the composer’s style has modified from the earlier Scythian Suite, though his fondness for bracing dissonance and rhythmic vitality remain, albeit watered down.

The Suite focuses in on several key episodes of Kijé’s fictional life: his birth (announced by a solo cornet/trumpet, military style), his falling in love (the plaintive saxophone), his wedding, a marvelous drinking song (“Troika”) that accompanies a wild ride in a horse-drawn carriage - one of Prokofiev’s most delightful concoctions - and finally Kijé’s passing, marked once more by a solo cornet/trumpet, sounding The Last Post, as it were.

The music is tuneful, colorful and direct, and everywhere suffused with Prokofiev’s pungent musical wit. It is full of sharp dynamic contrasts, vivid orchestration, and sheer musical fun, and has long been a staple of concert halls and the recorded catalogue.

Abbado is in his element here, and at every turn he and the Chicago players relish every saucy detail of this fun score. Yes, this is fun music above all else - cheeky, perky, relishing its own bravura. Once more the Chicago brass have a field day.

Chicago Brass Section in the 1970s

Chicago Brass Section in the 1970s

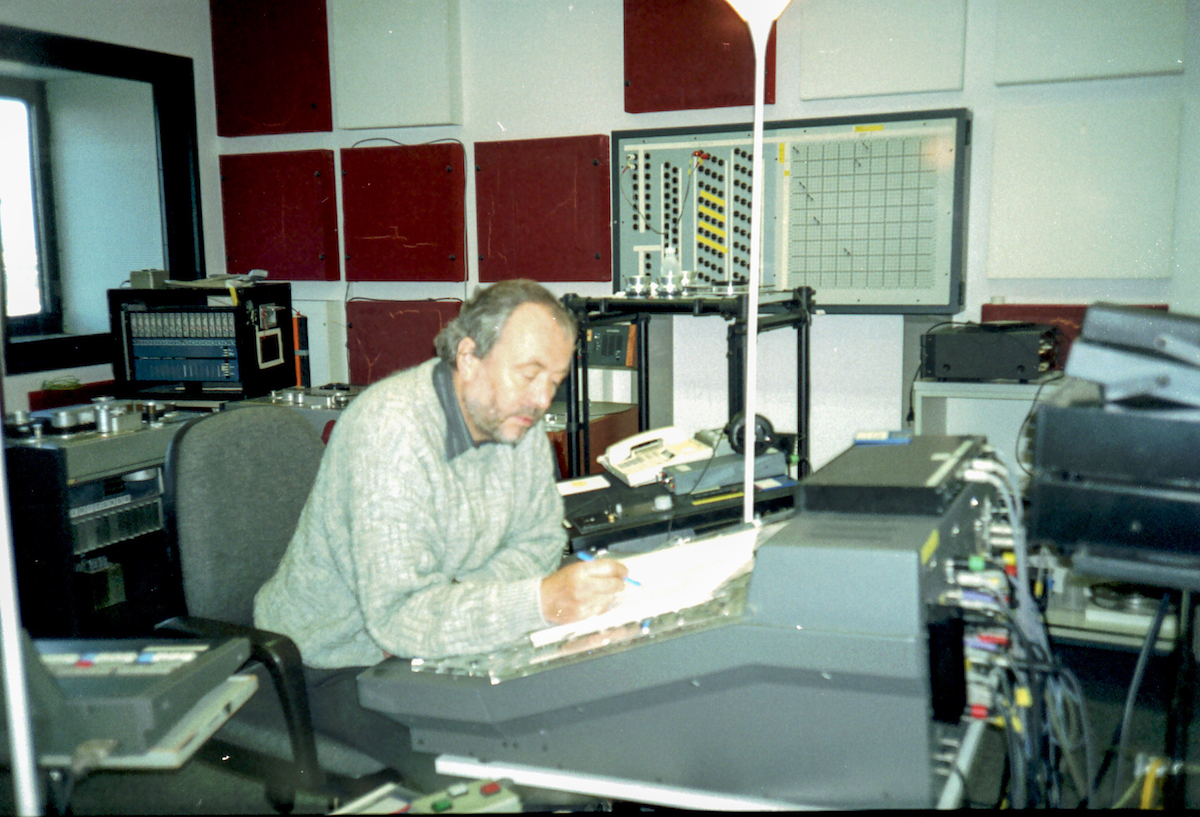

The recording is alert to all the audiophile virtues and then some. The Tonmeister/recording engineer on the original sessions was Klaus Hiemann (also responsible for the heart-stopping Pollini Polonaises I just reviewed, and the stunning Giulini Bruckner 9th Symphony reissued by DG last year). He is an engineer particularly admired by Rainer Maillard who mixed and mastered this reissue, and I will repeat his comments from that Bruckner review:

“Klaus Hiemann… was always interested in sound (in addition to the score). And he was the engineer at DG who took sound quality most seriously, both in the analogue arena and, especially, in the digital arena. He was always pushing for the highest quality. He was aware of the limitations of analogue and digital (they are different for each).”

Maillard also reflected on the important influence Hiemann had on him as he was learning his trade at DG:

“Klaus Hiemann always shared new ideas with us concerning ways to improve the sound of our recordings, mixes and masterings… Sharing knowledge amongst engineers was a normal part of the work culture at DG.”

Klaus Hiemann mixing at Recording centre Hannover-Langenhagen (Photo: Rainer Maillard/Emil Berliner Studios)

Klaus Hiemann mixing at Recording centre Hannover-Langenhagen (Photo: Rainer Maillard/Emil Berliner Studios)

Hiemann’s work on this record is stellar. You will gasp at the excoriating frenzy, the delicate moments of heart-breaking tenderness, the lurching dynamics. Throughout Sidney C. Meyer has once more demonstrated her considerable cutting skills in capturing all the action in the grooves - and then some…

CSO recording in Symphony Hall in 1982 with Solti

CSO recording in Symphony Hall in 1982 with Solti

The acoustics of Chicago’s Symphony Hall are caught maybe in a somewhat drier manner than you might expect, considering there are room ambience channels folded into the mix. But listen to how the floor rumbles along with the bass drum! This is “You are there” stuff. The acoustic overall comes closer to the sound you might hear from a film score recorded on one of the older Hollywood sound stages back in the day, before drenching film scores in reverb became a most regrettable thing - and is absolutely none the worse for that. Detail is free to emerge effortlessly, and when things get loud (which they frequently do) there is a sense of infinite headroom. This is yet another Original Source demo record.

THE COMPETITION

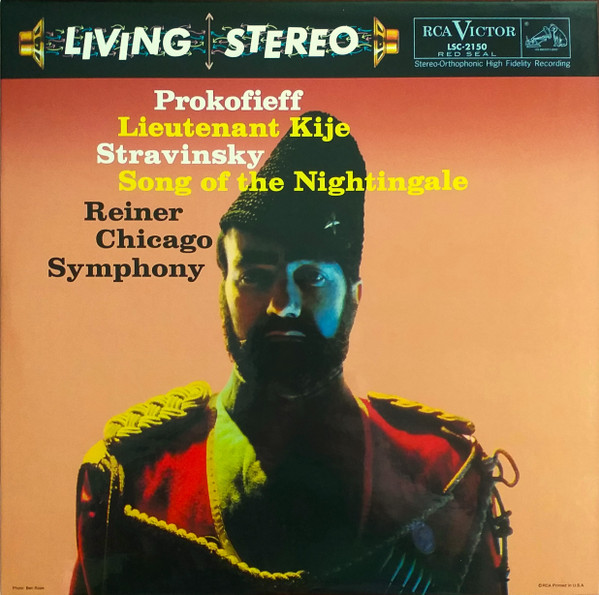

Which, as I mentioned at the top of this review, brings Abbado and his Chicagoans into direct competition with two long established audiophile classics. In Lieutenant Kijé the Chicago players compete with their younger selves under Fritz Reiner circa 1958 on one of the greatest of all Living Stereo titles, LSC-2150.

In the Scythian Suite, they are competing with Antal Dorati and the London Symphony Orchestra - again from 1958 - in a scorching Mercury Living Presence release, SR90006.

Both of these records are standouts in their respective label catalogues, and both personal favorites. I would never want to be without either.

For the Scythian Suite I had to hand the Classic Records 33 and 45rpm all-analogue reissues, both mastered by Bernie Grundman (the 45 after an upgrade to his mastering chain, I believe).

Antal Dorati

Antal Dorati

Dropping the needle on Dorati and the Londoners in 1958 I marveled anew at just how superb a band this was at the time (and still is), able to play absolutely everything to an incredibly high standard, even a score as less familiar as the Scythian Suite was back then. I also marveled anew at just how formidable this legendary Mercury recording is, capturing all the massive dynamics and Prokofiev’s glittering orchestration in that tell-tale Mercury manner: up-front, rich, bold. But as the record proceeded I began to notice two things. One, there were places where the orchestra betrayed a slight lack of the ultimate tightness of ensemble, in particular in the busier sections of the third and fourth movements: you can tell they’re recording this without the nth degree of rehearsal before rolling tape, and it’s a less familiar score. No such looseness with Abbado and the CSO, drilled to perfection over decades by Fritz Reiner and during this period of the 1970s by Georg Solti.

Two, the very nature of Mercury’s minimal miking technique is no match for DG’s multi-miked ability to not only capture all the instruments in detail, but then to balance them in a slightly deeper soundstage without sacrificing clarity and impact. The standout comparison was the horns in both recordings. For example, in that “Indian attack” moment at the beginning of the second movement, Dorati’s horns are not as immediate: they are dominated by the trombones who sound like they are in front of them, even though the horns carry the tune. With Abbado you can clearly hear the horns are further back on the stage (or at least sound that way because of their rear-facing bells), yet they are also in exactly the right balance with everything else - carrying the tune and therefore more upfront in the balance.

Orchestral balance was the thing I kept coming back to as the defining difference between the two recordings. The Mercury method had everything there, vivid, three dimensional, sometimes almost too vivid (Dorati kicks off the piece at one hell of a lick - it’s thrilling). With Abbado you get a more consistent sense of the whole stage, where all the instruments are, and the hall acoustic: nothing crowds the microphones like it sometimes does on the Dorati. Yet everything has the same impact as on the Dorati.

Also Abbado just has such an innate feel for this music: he can turn from savagery to delight in a heartbeat. Everything is rhythmically as taut as taut can be, and yet he can loosen things up when called for. He finds the moments of whimsy, magic and romance in a score than can easily just overwhelm like a pile driver. And the engineering work of Klaus Hiemann follows him around every hairpin turn effortlessly. It is something special to listen to, how Hiemann captures every delicate shade and nuance along with the power and the glory of this dense, complex score.

With Lieutenant Kijé I was listening to the Classic Records reissues at 33 and 45 and the Analogue Productions 33, again all mastered by Bernie Grundman.

Fritz Reiner with the CSO

Fritz Reiner with the CSO

Oh man, this was going to be difficult to choose, if choose I must. This may be my favorite of all the Reiner Living Stereos (along with the Bartok Concerto for Orchestra and Music for Strings, Percussion and Celeste), as much for the music (including the barely known but glorious Stravinsky Song of the Nightingale as the coupling), as for the performance and sound quality. But man oh man, do Abbado and DG give Reiner & co. a run for their money. Maybe the Living Stereo has the edge in terms of the silkiness and that tangibility of the sound that was a Living Stereo hallmark, all down to those old microphones, valve amplifiers etc. and brilliant engineering. For example, the pizzicato and bowed string chords simply have that palpable tubey twang which makes this former ‘cellist go weak at the knees. But the Chicago players and the DG team are no slouch in the audiophile virtues department either. All the colors of this very colorful score emerge effortlessly: performances and recording are full technicolor. And the solo work maybe even exceeds that of the earlier recording; certainly the all important saxophone solos have more presence, and the solo trumpet of Adolph Herseth lacks nothing in comparison to his younger self for Reiner. And maybe Abbado just has the edge over Reiner in flexibility, a willingness to let the music “swing” when it needs to, which Prokofiev always benefits from. Also, the huge dynamic range of the DG is something else, plus that sense of the orchestra on the stage, in that hall, is palpable. Very hard to pass on all that.

So I’m not going to choose! Either way you’re a pig in analogue clover.

To sum up, if you already have the Reiner and Dorati in one of those reissues (and the 45s undoubtedly give you more of everything), you don’t really “need” to go out and buy this new Original Source version. But why would you want to miss out on all this phenomenal fun? I mean - really!

Originally I wasn’t going to give this record a coveted 11/11 for Music and Sound. I was going to be thoughtful, temperate, and go with a parsimonious 10/10 - because, well, I can’t just keep handing out these 11 gradings (I so wanted to give 11/11s for the Messiaen and Pollini releases but held back). But then I gave this record another spin after listening to the Abbado Mahler 2 (for reasons I will elaborate upon in that upcoming review), and I told myself who was I kidding! This is such a kick-ass record (I concur 100%_ed.). And yet again I am discovering that Klaus Hiemann is truly one of the great sound engineers. More of his catalogue please, DG and EBS.

And if this Prokofiev double-bill sells well, maybe DG will give the Original Source treatment to Abbado's superlative 1980 version of Alexander Nevsky, one of the best accounts out there.

Abbado with the CSO in 1984

Abbado with the CSO in 1984

With Abbado and the Chicagoans, there is such weight and mass to the orchestral playing that at times it feels like one is being charged by a huge slavering beast, jaws ajar, saliva a-flying, intent on chomping down on you - the tasty morsel. Only to then curl up like a purring pussycat in your lap, all ingratiating cuddles, beguiling you with its soft siren song.

You want to miss out on that? I certainly don’t. (“Good beastie…!”)

I can never have too much first-class Prokofiev in my collection, and this one shoots right to the top of the pile of “Essential”. Miss it at your peril.

Portrait of Prokofiev by Pyotr Konchalovsky (1934)

Portrait of Prokofiev by Pyotr Konchalovsky (1934)

Limited Edition of 3600 numbered copies.

Available for purchase at DG's German site, and stateside at Acoustic Sounds and Elusive Disc.

.png)