Chopin for the Ages - The Original Source does Pollini Proud

A Catalogue Benchmark is given a Formidable Sonic Refresh

1849 Daguerrotype of Frédéric Chopin

1849 Daguerrotype of Frédéric Chopin

For me, many of the highlights of the Original Source Series so far have been the smaller-scaled instrumental and chamber music releases: Emil Gilels’ Beethoven recital, Schubert’s “Trout” Quintet, and the just released Messiaen Quartet for the End of Time. I always felt that DG’s piano sound of the 70s as represented on the original vinyl releases was undernourished, which meant that titanic performances by the likes of Gilels, Martha Argerich, Wilhelm Kempff, Daniel Barenboim, Lazar Berman and others did not register as powerfully sonically as they deserved to.

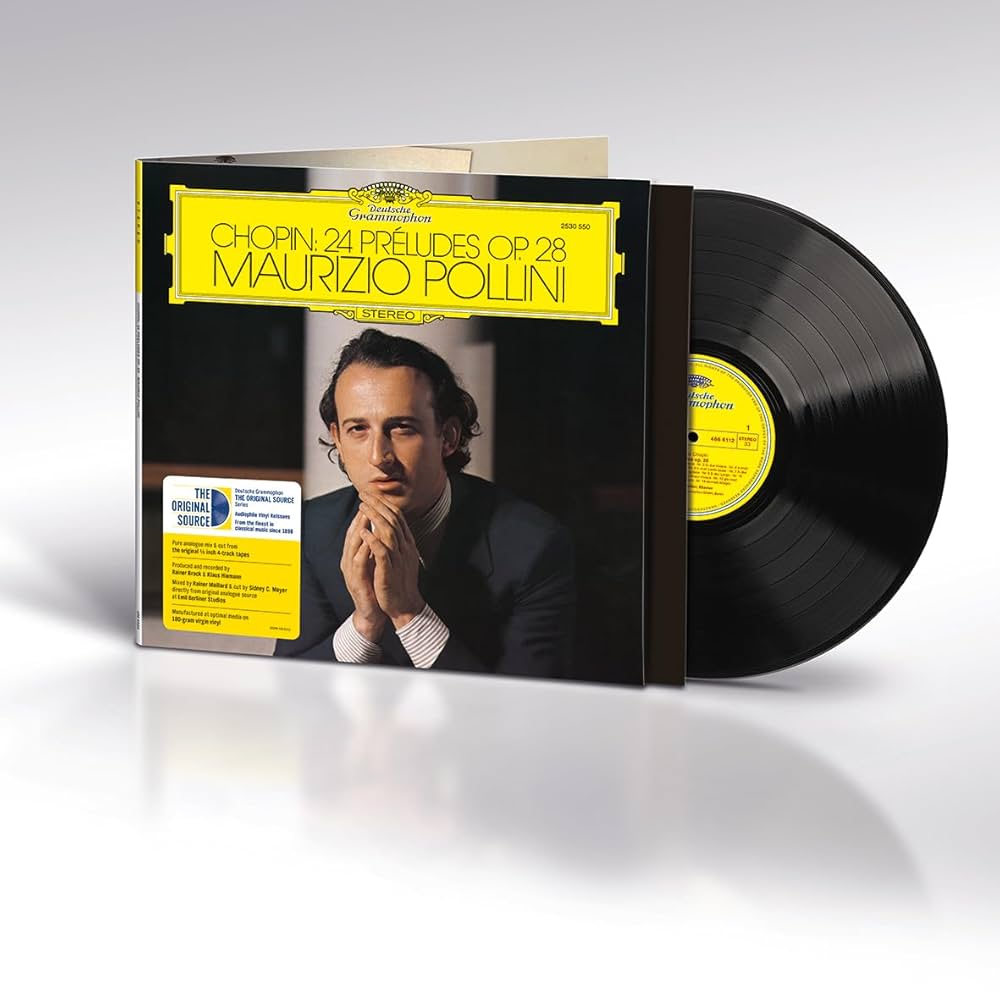

That Gilels Beethoven record especially indicated what we had been missing, and the release last year of Maurizio Pollini’s iconic traversal of the Chopin Preludes was similarly revelatory and drew a suitably enthusiastic response from my colleague Michael Johnson.

I expressed my own enthusiasm for this reissue on my YouTube channel. I felt it was one of the most spectacular piano records out there.

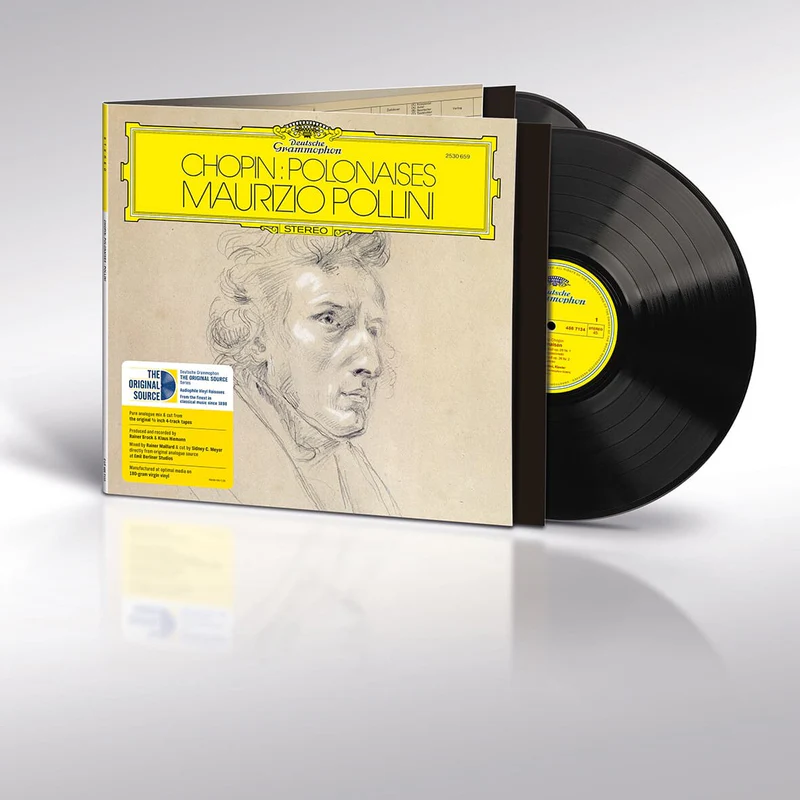

So expectations were sky high for this release, especially since - because of long original side lengths well in excess of 30 minutes - the folks at Emil Berliner Studios decided to cut at 45rpm, presented on a double LP set. (Even at 45rpm, side lengths are similar to certain classical and pop records cut at 33 1/3, and because each of the Polonaises is self-contained, flipping the records does not interrupt musical flow or enjoyment - the principal argument against 45rpm classical records).

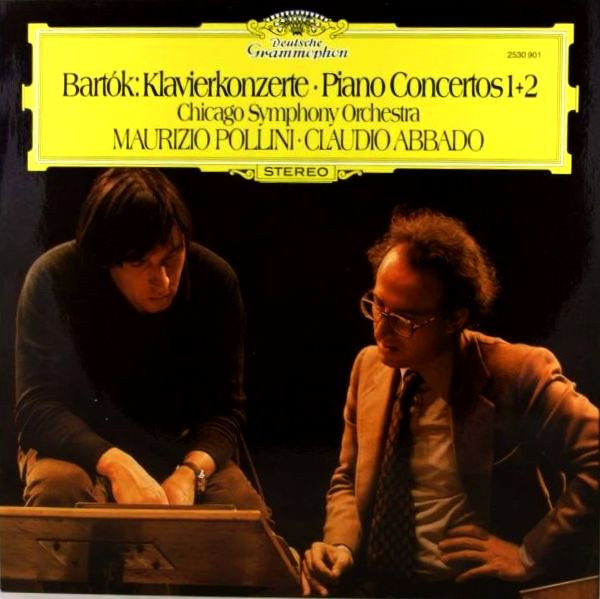

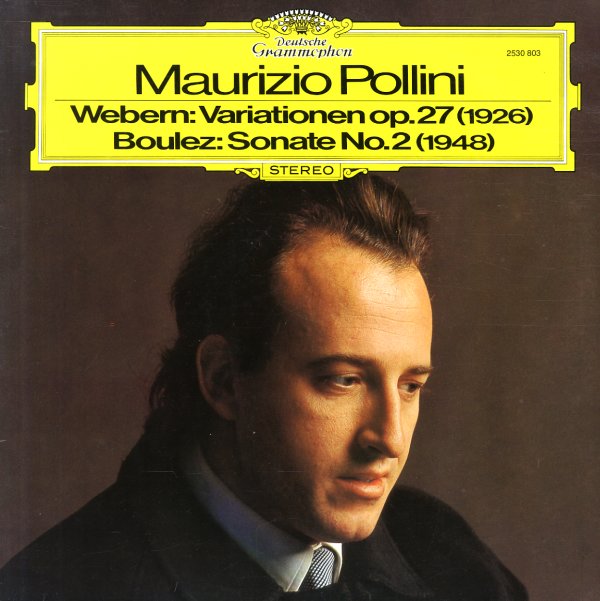

I make no bones about my love for Pollini’s playing (even though, alas, I never heard him in concert), and his passing in 2024 felt momentous. I collected all his original albums when they were first released. He and Martha Argerich were the jewels in the crown of the younger generation of pianists signed to the Yellow Label in the 1960s and 70s. His formidable technique was married to a more modern way with the great masterpieces of the piano repertoire, an approach that peeled away many years of accumulated performance veneer, akin to restoring an Old Master to the colors that would have astonished its first viewers. Add to that a certain Italianate, aristocratic bearing which would charm and insinuate when you least expected it. Alongside his forays into Chopin, Beethoven, Schumann and Schubert during the 1970s, there was his run of revelatory recordings of modern music, beginning with his fire-blowing account of Stravinsky and Prokofiev, still unmatched in the catalogue.

German release featuring the alternative artwork cover created by Peter Wandrey

German release featuring the alternative artwork cover created by Peter Wandrey

Then came his pioneering set of Arnold Schoenberg’s piano music, an album which prompted me to learn several of these works myself. It is still unmatched.

His album of the first two Bartok piano concertos was again an instant benchmark, which it has remained.

You will hear more than a few pianists refer to his incandescent coupling of Pierre Boulez and Anton Webern as a major inspiration - at the time it was almost unheard of for a major artist like Pollini to release this kind of demanding modern music on a major mainstream label.

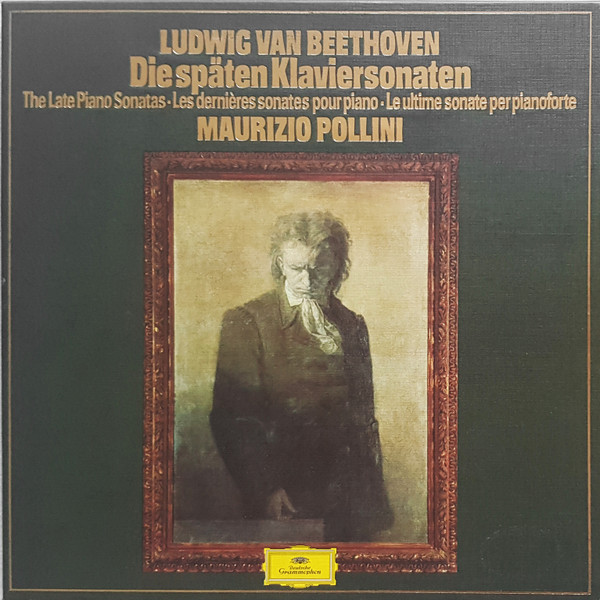

Pollini went on to champion contemporary Italian composers like Luigi Nono and Giacomo Manzoni throughout his career. No doubt his deep interest in modern music helped inform his approach to the classics, and nowhere is this more evident than in his set of the late Beethoven sonatas, still to this day a benchmark in the catalogue (and a prime candidate for an Original Source makeover).

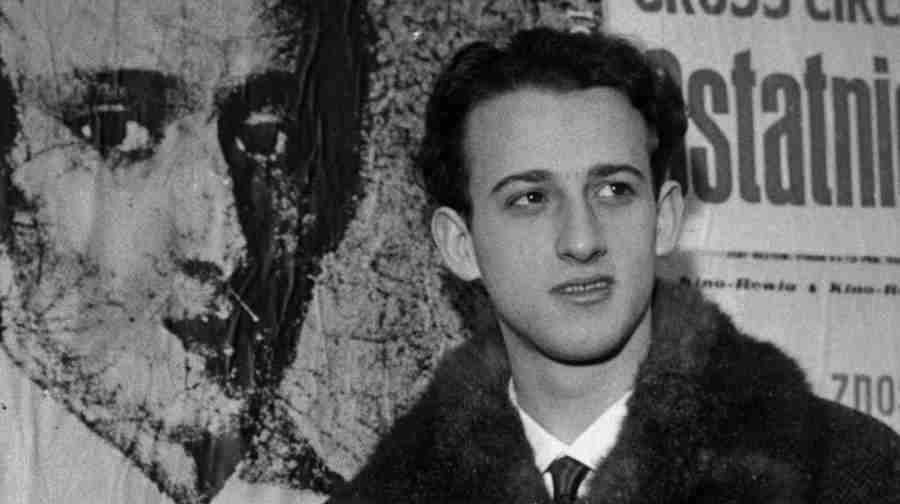

But it was with Chopin that Pollini first made his name, winning the International Chopin Piano Competition in 1960 at the age of 18. Famously, the head of the jury, Artur Rubinstein, declared: “That boy can play the piano technically better than any of us," (remembered by Pollini himself more as a mischievous dig at the other jury members than as a pronouncement of the young pianist's supremacy). DG released a live recording of his competition performances on its Heliodor imprint.

In later years, Pollini talked about the invaluable piece of advice Rubinstein gave him after the competition. Resting the middle finger of one hand on his shoulder, Rubinstein told him to use just this level of weight and pressure on the keyboard, revealing that by doing this he never got tired when playing. Pollini remarked that just through this one finger he could feel the full strength of Rubinstein's arm and shoulder. This was how Rubinstein achieved his glorious sound (and it was glorious indeed, even when I heard him perform live in his 80s). "The more I think of it, the more I find it precious", noted Pollini.

Pollini at the Warsaw International Chopin Competition in 1960

Pollini at the Warsaw International Chopin Competition in 1960

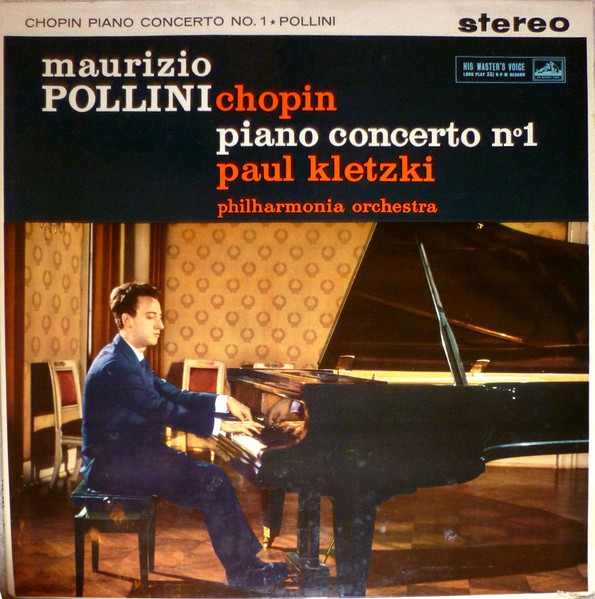

His first major label release was of the First Piano Concerto with Paul Kletzki conducting the Philharmonia Orchestra on EMI.

Also for EMI, Pollini recording the complete Chopin Études, but did not approve release of the edited tapes. These would not see the light of day until 2011 on Testament, and offer a fascinating comparison with his 1972 traversal for DG.

Interestingly, instead of immediately embarking on a busy concert and recording schedule, Pollini took time off to study, and in particular to study with another Italian piano great, Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli, whose cool, precise and even reserved approach came to inform Pollini’s own playing.

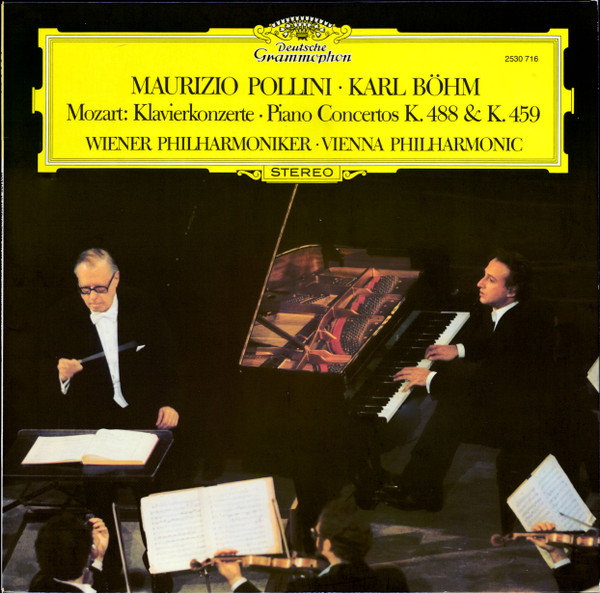

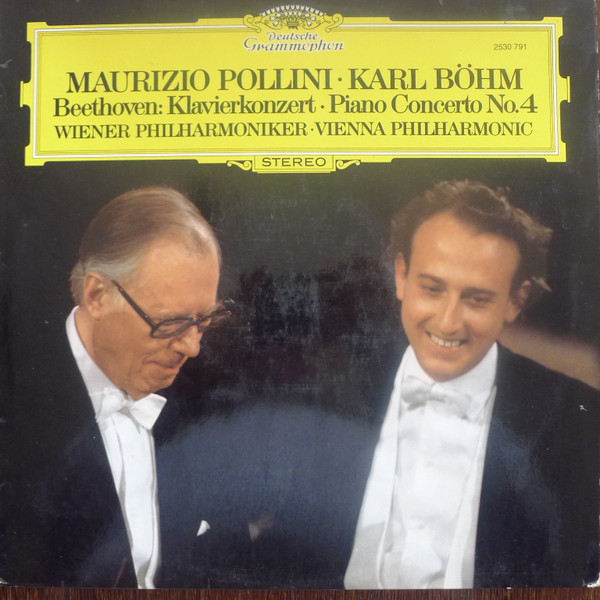

In fact, one of the regular criticisms one would hear of Pollini throughout his career was that his style was too clinical, too emotionally reserved. I have never found that to be the case, and indeed his unvarnished, un-romanticized approach to even the most romantic works, allied to his formidable control of tone and dynamics, means that his recordings have aged very well indeed, and remain formidable contenders in an insanely crowded field. Surprises also lurk in his catalogue, like his wonderfully warm but precise Beethoven and Mozart concerto recordings with the Vienna Philharmonic and the redoubtable Karl Böhm at the helm.

Böhm - doyen of old-school German conductors - is the last person you’d expect to vibe with Pollini, but it was a perfect match, and these recordings are true treasures (and again prime candidates for Original Source reissue).

Pollini’s debut with the Yellow Label came in 1972 with that aforementioned Stravinsky/Prokofiev album and another benchmark, of the Chopin Études.

More Chopin came with that set of the Préludes in 1975, with the Polonaises under consideration here following the next year. All were acclaimed upon arrival.

It is worth quoting at length here Gramophone critic Bryce Morrison’s assessment of these performances upon their CD reissue:

“Shorn of all virtuoso compromise or indulgence, the majestic force of his command is indissolubly integrated with the seriousness of his heroic impulse. Never have I been compelled into such awareness of the underlying malaise beneath the outward and nationalist defiance of the Polonaises. The tension and menace at the start of No. 2 are almost palpable, its storming and disconsolate continuation made a true mirror of Poland’s clouded history. The C minor Polonaise’s denouement, too, emerges with a chilling sense of finality, and Pollini’s way with the pounding audacity commencing at 3'00'' in the epic F sharp minor Polonaise is like some ruthless prophecy of every percussive, anti-lyrical gesture to come. At 7'59'' Chopin’s flame-throwing interjections are volcanic indeed, and if there is ample poetic delicacy and compensation (notably in the Polonaise-fantaisie, always among Chopin’s most profoundly speculative masterpieces), it is the more elemental side of his genius, his ‘canons’ rather than ‘flowers’ that are made to sear and haunt the memory.”

Morrison goes on to address the oft-leveled complaint about Pollini’s “coldness”:

“To say that Pollini is ‘cold’ (a recent jury colleague; his exact description seemed to me as blinkered as it was unprintable) is to miss the point, to show an incapacity to identify with ‘other points of view’, with possibilities that lie at the very heart of re-creation. Others may be more outwardly beguiling (Pollini is already a wide step from Rubinstein’s belle époque elegance or Horowitz’s reminder of Russian romantic pianism at its most volatile) but Pollini’s magnificently unsettling Chopin can be as imperious and unarguable as any on record. That his performances are also deeply moving is a tribute to his unique status.”

It was only with the advent of LPs that complete sets of the Polonaises came to be released. Normally audiences would be exposed to these works as part of larger recital programs, intermingled with, say, a Chopin sonata and a selection of nocturnes, waltzes, preludes etc. I mention this because hearing them all together as a set is to invite a certain level of musical indigestion, by virtue of their intensity derived from the concept of each work being a world unto itself, expressing a wide range of emotion through a concentration of varied musical material. But Pollini has taken this into account, thinking of these works as a cycle, with a clear emotional progression from the early works which are more obviously straightforward to the final ambiguities and darkness of the Polonaise-Fantaisie.

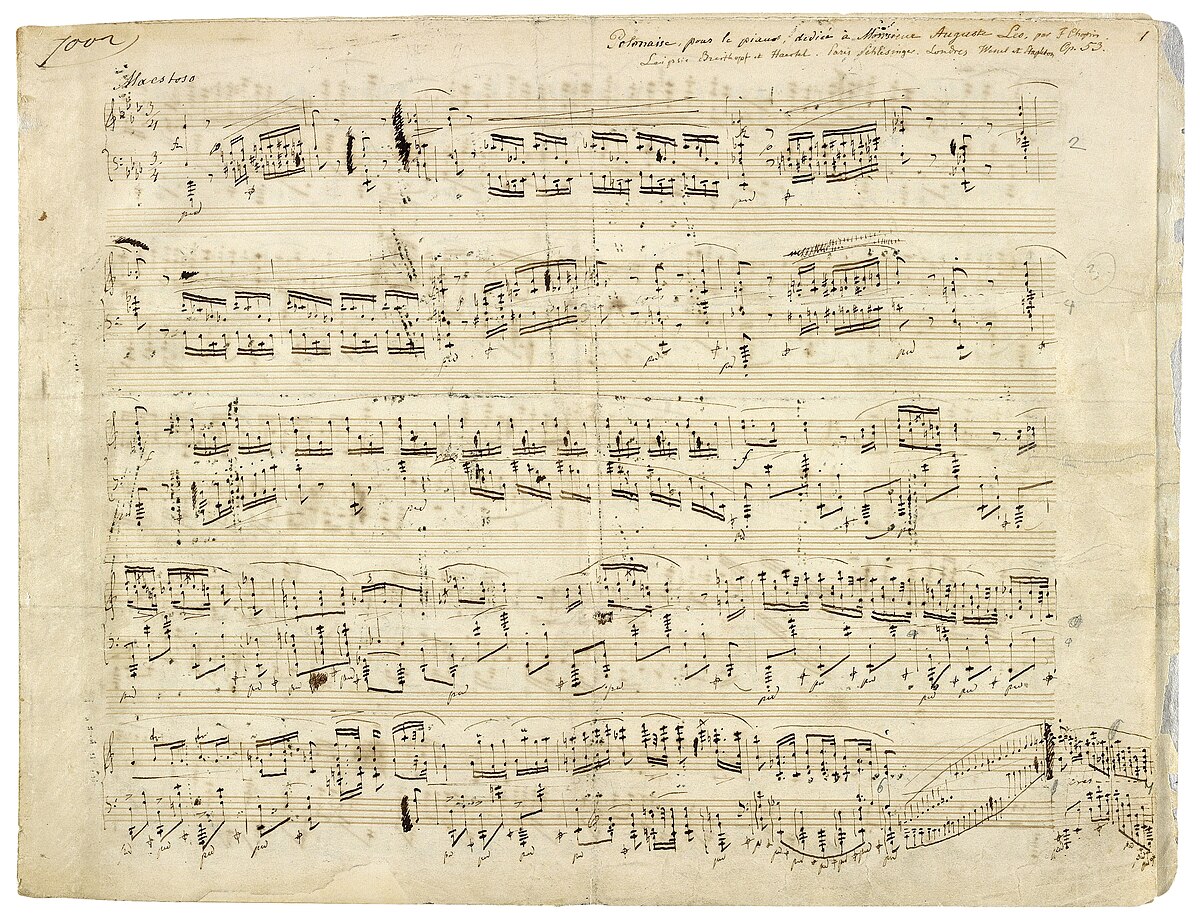

Autograph Score for Chopin's Op. 53 Polonaise

Autograph Score for Chopin's Op. 53 Polonaise

Like much art music, the Polonaises had their origins in dance music going as far back as the 16th century. The polonaise was a measured, stately dance for couples, in 3 time, similar to the waltz. By the time of Chopin in the early 19th century, the polonaise had become identified with Polish nationalism, at a time of political turmoil after the country had been divvied up between Russia, Prussia and Austria (an independent Polish state ceased to exist until it was reestablished in the aftermath of World War I). As Uwe Kraemer writes in his sleeve note for this Original Source reissue, reprinted from the original release:

“Chopin’s attitude to the polonaise underwent a fundamental change after the final departure from his native country in 1830. The longer he remained in exile, separated from his Warsaw friends, the further he departed from the gallant style. Chopin created in his late polonaises symbols of his total identification with the sufferings of his people. Indeed they are like confessions from a man with his throat cut.”

Pollini’s renderings focus in on the heroic and tragic subtext of these works. This is music of defiance and celebration of the nationalist spirit. (It's hard not to listen to these performances and not hear overtones of the current Ukrainian resistance to Russia's assault, let alone Poland's own rekindling of a nationalist spirit arising from similar resistance to its neighbour's territorial aspirations: this is definitely music that has found new relevance in this current tragic moment for this region of Europe). There’s little sense here of that beguiling quality so common to much of Chopin’s music: these are elemental, unsettling performances of music that came from the core of Chopin’s own sense of personal and national identity.

The famous 1838 Portrait of Chopin by Eugene Delacroix

The famous 1838 Portrait of Chopin by Eugene Delacroix

The piano sound itself as captured on these records aptly reflects the music for which it is a vehicle: it is direct, strong, detailed, un-romanticized, powerful - and very much the “Pollini Sound”. It also happens to be, as with his traversal of the Préludes in its Original Source incarnation, stunningly immediate and lifelike.

THE POLLINI SOUND

Let’s talk a little about the “Pollini sound”. It is very distinctive and is a major factor in his recordings and what makes them special. It is not merely a product of his technique and interpretative approach, nor of the recordings themselves and how they were achieved (more on this later).

It derives at its heart from the very specific manner in which Pollini had his pianos voiced and tuned throughout his career by his piano technician, Angelo Fabbrini. Most people would be surprised to know that many of the top piano virtuosi are very specific in the choice of instrument they use, and how it is prepared, and the degree to which a soloist’s “sound” can change according to how his piano is voiced. Daniel Barenboim in recent years even had a piano specifically designed for him from scratch. Different piano manufacturers are favored by different players: some go for the classic Steinway, some for the rich Bösendorfer (my personal favorite, and used by Anne Dudley on her wonderful prepared-piano reinvention of The Art of Noise catalogue); Sviatoslav Richter famously went all in with the nascent Yamaha brand as it was getting established in the market-place during the 1970s (Yamahas are now almost more ubiquitous than Steinways).

Pollini always favored Steinways, but Steinways specially prepared, voiced and tuned by Angelo Fabbrini. As the Original Source reissue of the Préludes made plain, this resulted in a lighter (but still powerful) bass and an almost crystalline middle and upper register, though still possessed of warmth. It was a sound which favoured transparency and clarity over a rich and lush patina (a fact I discussed in my video comparison with Vladimir Ashkenazy’s more overtly romantic reading on Decca from 1978 - begins at 17:30).

I found the piano sound on that Original Source Préludes to be some of the most lifelike, tangible piano sound I’ve heard on any record, fully capturing every minute detail of Pollini’s breathtaking pianism.

Angelo Fabbrini

Angelo Fabbrini

Fabbrini would travel with Pollini to concerts and recording dates, making sure the pianos met Pollini’s exacting remands. How was this sound achieved?

It’s worth quoting at length this article from the Boston Musical Intelligencer by Christopher Greenleaf:

“Maurizio Pollini’s touring Hamburg Steinway-Fabbrini concert grand exhibits exceptionally ravishing tonal and technical characteristics. The fact that this is a piano well outside our modern norm begs a number of questions, among which is, “Why don’t we regularly hear instruments of this subtlety and beauty?”

“But first, what goes into the production of a Hamburg Steinway-Fabbrini concert grand? Italian piano technician and entrepreneur Angelo Fabbrini, from Pescara, Abruzzo, purchases new Steinways from that firm’s celebrated Hamburg atelier and subjects them to minute technical fine-tuning, replaces or substantially rebuilds numerous crucial action components, and reworks the interaction between strings, bridges, and soundboard. The sound of the rebuilt instruments reminds one of the finest surviving pre-1912 Blüthner concert grands (from Leipzig) and of 19th-century concert instruments by Mason & Hamlin, the 19th-century Boston firm whose pianos were, by a comfortable margin, the highest-priced in this country.

“The Fabbrini design does not sustain tone for quite as long as these older pianos and the treble is gleamingly dark rather than the ethereal shimmering silver of the Blüthner Aliquot design. Unlike a standard New York Steinway, in which shadings under mezzo-forte can be difficult to control, sometimes even to produce, the Fabbrini Steinways offer the easy, wide dynamic range typical of pre-1920 pianos by the great German, American, and Austrian builders. The Fabbrini fortissimo is magnificent, but it is not as loud as the brash New York roar. Its top dynamic reaches are capable of considerable variation, and the tone production can be built up to near-orchestral volume without strain. [Heard frequently in the Pollini Polonaises]. In the course of the Celebrity Series of Boston concert at Symphony Hall on April 25, [reviewed here] Maurizio Pollini time and again called forth ppp and fff trills in the bottom two octaves, as effortlessly and clearly as at middle dynamic levels. Forte in the right hand against piano and mezzo-piano in the left became part of this recital’s wide dynamic vocabulary.

“Once an expressive norm for concert instruments, this clear-as-a-bell opposition of dynamic levels is heard infrequently these days. From a purely piano technical perspective, an occasion like this recital lodges in lifelong memory. Mr. Pollini travels worldwide with his Steinway-Fabbrini. Other Fabbrini artists have been Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli, Sviatoslav Richter, and András Schiff.”

(You can read the rest of this excellent article here).

Angelo Fabbrini at a tribute concert arranged by Martha Argerich (r.)

Angelo Fabbrini at a tribute concert arranged by Martha Argerich (r.)

The “Pollini Sound” on record was also the product of a meticulous and exacting process developed by the pianist over many years. After 1986 (so after these earlier Chopin recordings), Pollini worked exclusively with Christopher Alder at DG, and in the box set of the pianist’s complete DG recordings, Alder gives a detailed account of their working methods.

Longtime producer of Pollini's post-1986 DG albums, Christopher Alder

Longtime producer of Pollini's post-1986 DG albums, Christopher Alder

While not directly applicable to these earlier 1976 Polonaises, it is clear from the session documentation that the pianist was already working towards the exacting method outlined by Alder, so it bears repeating.

That method would involve Fabbrini arranging for several different instruments to be available in the recording venue, Pollini trying different ones, Alder recording them, before settling on a choice for each work and the final sessions. Then numerous different microphone placements would be tried.

Alder:

“It is a slow process. The variations are tiny - we are talking about moving a microphone located some 5 metres away, only a single centimetre. As with many aspects of recording, the advantage of, say, a brighter sound may be achieved at the cost of reduced bass or increased reverberation. It depends on the hall. The final decision ultimately comes down to taste and mood, and it requires great concentration. Once the parameters are set, we are normally finished for the day.”

Once the session itself would begin…

“Unless there is a problem with the piano, he will play through the complete program. Occasionally he repeats a movement, but that seldom happens in the first couple of days. He goes upstairs to change his shirt - this is warm work - and drink an espresso from our machine. During each pause Fabbrini is at work retuning and voicing the piano. Pollini discusses certain passages with me and tells me what he is after: for example, a sense of relaxation in tempo before a certain passage, but it should not be perceptible to the normal listener. These conversations may seem haphazard, but by the end of the sessions, somehow, we have gone through everything. He always asks for my comments… Pollini will then go down and play through the program again, come up, change, discuss - or talk about politics, a favourite subject - and then play one last time before leaving for dinner around 8pm.”

This process would then repeat itself over many subsequent weeks, with Pollini listening to the takes in-between. Alder:

“I think he needs to be convinced that he has done everything in his power to produce an optimal result and never be left feeling he should have taken more time… Interestingly, after 30 years of recording with him, I can still detect no pattern in the takes that eventually make it on a disc. Sometimes they all come from the first recording period, sometimes from the second; sometimes they are a mixture of the two.”

The same time-consuming steps over many weeks were not taken on these earlier Polonaises sessions, but one can assume something similar was being developed by the artist and the recording team even at this early stage. From the included paperwork one can see that sessions were spread over many days (op. 44, op. 63 and 61 being recorded over seven days alone), with a note also included in which Pollini requests a re-edit of the master.

The Tonmeister/recording engineer was Klaus Hiemann, who - like Klaus Scheibe (responsible for the Messiaen Quartet for the End of Time sessions) - was someone whom Rainer Maillard (who mixed and mastered this reissue) admired enormously and who shaped his early career and training at DG:

“Klaus Hiemann was a good pianist. But he was always interested in sound (in addition to the score). And he was the engineer at DG who took sound quality most seriously, both in the analogue arena and, especially, in the digital arena. He was always pushing for the highest quality. He was aware of the limitations of analogue and digital (they are different for each).”

I find myself increasingly of the mind that Hiemann was one of DG's finest sound engineers, and this record further confirms that opinion.

THE ORIGINAL SOURCE REMASTERING - AT 45rpm

I went into this wondering how Rainer Maillard and Sidney C. Meyer at Emil Berliner Studios could possibly top the sound they achieved on the OSS reissue of Pollini’s Chopin Préludes. Well, they’ve done it, and I don’t think it’s merely a matter of the records being cut at 45rpm, a first for the Original Source Series (and in no way an inconvenience because of the nature of the program of works on these LPs). The EBS team continues to refine its methods and the result is a remarkable consistency of superb sound on these reissues. They are knocking it out of the park - and it's all I can do to resist giving all these new releases the hallowed 11/11 ratings reserved for Excellence in extremis!

From the opening bars of op. 26, No. 1, one is aware of the power and force of Pollini’s playing. It will set you back in your listening chair. These are works in which the pianist often thunders, with huge chord clusters spelling out heroic utterances. This can very quickly impart a sense of sonic overload, a feeling of strain and fatigue, but here the density is handled effortlessly. Then the music subsides into a more lyrical strain, with Pollini articulating the melody and its accompaniment with a delicacy and perfectly judged rubato that recalls a moonlight serenade.

This juxtaposition of the heroic and the reflective lies at the heart of these works, and as they progress one hears how Chopin is ever more experimental in his deconstruction and expansion of the traditional polonaise form. Even classical novices will recognize many of these melodies, and old warhorses of the concert hall like op. 40, No. 1 and op. 53, are rejuvenated through Pollini’s exacting traversal.

I find myself most drawn to the darker, more sinuous of the Polonaises. As early as op. 26, No. 2 one can hear Chopin reaching into more chromatic, experimental territory, and Pollini excels at melding these tendencies with the more conservative aspects of the form. Op. 40, No. 2 announces its darkness with a twisting melody in the bass, and here one really appreciates both how perfectly Pollini’s piano has been voiced, and how completely the DG engineers have caught its sound. The bass is never overly rich or ripe, but it has tremendous heft and clarity. The upper registers gleam and glisten, and some of Pollini’s runs in the right hand are breathtaking not just in their articulation but also in their steely power. Over and over again I found myself reveling in the lifelike sonority of the piano in front of me, as I was able to discern every minute detail of Pollini’s articulation and tone, even to the extent of hearing the piano mechanism itself in action.

As Bryce Morrison noted in his review quoted earlier, Pollini captures the compositional and aesthetic progression of the Polonaises to perfection. These performances definitely feel like a cycle, moving inexorably towards the final op. 61 Polonaise-Fantasie, where there is a sense of entering new, uncharted territory. Every phrase speaks equally of sadness and fervor, of defiance and loss. You can hear Chopin straining at the limits of his form and harmony, reaching for a musical language of the future. Over and over again I found myself hearing pre-echoes of the late piano music of Franz Liszt, shorn of all unneccessary virtuosic flourish, grasping at the experimentalism of the 20th century. It is a most remarkable work, and not surprisingly Pollini is able to make it sound both indelibly “Chopinesque” and also more forward-looking, more modern. Over and over again there are moments which will take you completely by surprise, such as the series of simple chords progressing through unexpected harmonic changes that lead into the final heroic statement, which itself does not round off the piece, but dissolves into something more subdued for the end. It’s all quite spellbinding.

In short, this is piano playing of rare distinction, a bona fide classic of the catalogue, given a sonic makeover that allows Pollini’s art to emerge full-force. As Gramophone put it: “Other pianists may be more outwardly beguiling, but Pollini’s magnificently unsettling Chopin can be as imperious and unarguable as any on record. That his performances are also deeply moving is a tribute to his unique status.”

Presentation is amongst the best in the original Source series, replicating the fascinating series of photos of original manuscripts etc. from the original release on the back cover. All four LP sides presented the music immaculately, with nary a tick or pop.

Another Original Source essential.

The following is a lengthier, more detailed documentary, full of insights from the pianist, and replete with fascinating archive footage, and some great performance extracts from a very wide range of repertoire (including Stockhausen and Boulez!). From 42:00 to 46:30 you will see Pollini and Fabbrini preparing his piano for a concert, and Pollini talks about the challenges of varying acoustics in different halls. It's well worth taking the time to watch it in full:

Limited edition of 3700 copies. Available from the DG shop, or stateside from Acoustic Sounds and Elusive Disc.

.png)