The Electric Recording Company Reissues Rare, Beautiful Folk Gems from Both Sides of the Pond

Vashti Bunyan and Terry Callier expand ERC's palette of lavish reissues

What makes a record valuable? There's price, rarity and condition, obviously, but to this listener, other things are more important. The record’s provenance, my personal history with it, my emotional connection to the music encapsulated in the grooves. It's about stories and emotions. For these and other reasons, one of my most valuable records is one you can pick up on Discogs for five bucks.

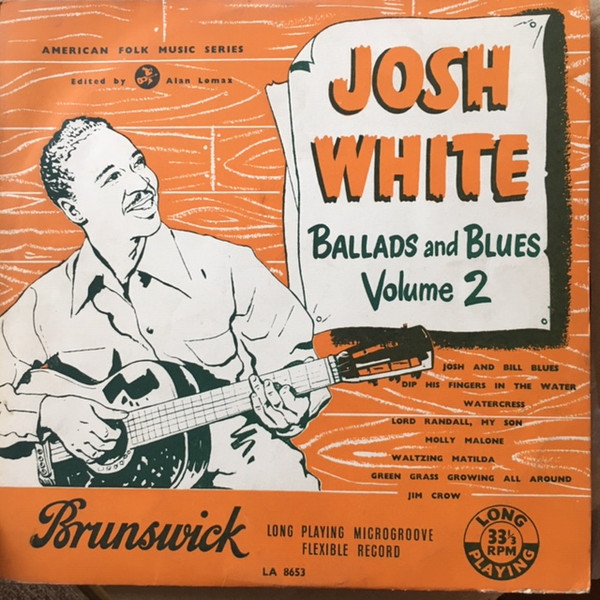

Ballads and Blues Vol. 2 is a UK ten inch pressing of a Brunswick collection of sides by the folk blues singer Josh White, selected by Alan Lomax for the American Folk Music Series. It is the first blues album I ever heard. The record was my late father’s, sticking out like a sore thumb in his collection of mostly classical music and mainstream jazz. I never got around to asking him how he came by the record, but I still have it and cherish it, and not only for sentimental reasons. White’s soft singing voice, melancholic melodic style and Piedmont guitar picking primed me not only for a lifelong love affair with blues and folk, but also, indirectly, for falling hard for the sound of Terry Callier (1945-2012).

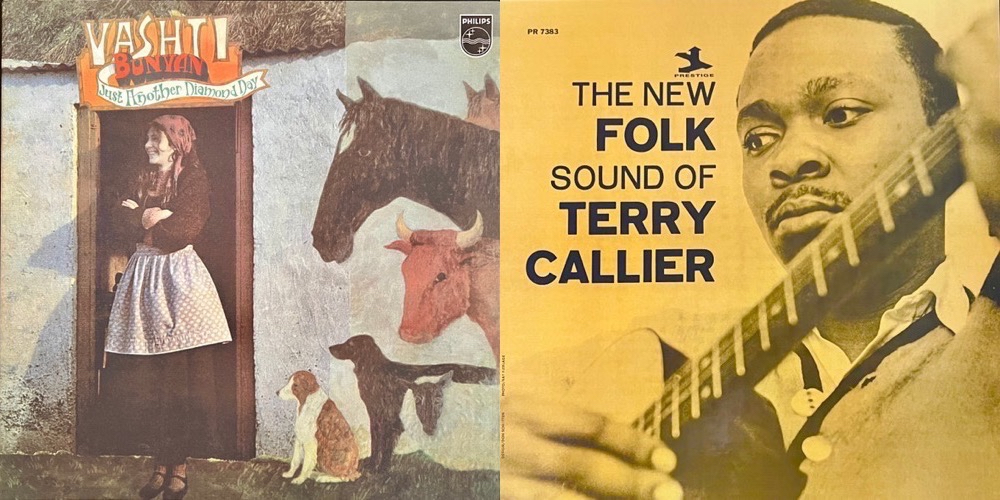

The Chicago-born Callier came up in a remarkable group of local musicians in the early 1960s, with Curtis Mayfield, Jerry Butler and Ramsey Lewis. He was discovered by the producer Samuel Charters, and released his first album in 1965 on Prestige. The New Folk Sound of Terry Callier was an amazingly accomplished debut of sweet, yearning and blues-infused folk music. Later he moved to Chess subsidiary Cadet and made three great, but underappreciated soul-tinged albums under the guidance of Chess producer Charles Stepney, among them the standout What Color Is Love. Callier had a revival on the british soul-jazz scene of the 1990s. He was signed to Gilles Peterson's Talkin' Loud label, made six albums between 1999 and 2009, collaborating with Beth Orton, Paul Weller and Massive Attack, among others. He died of cancer at 67, in 2012

The Chicago-born Callier came up in a remarkable group of local musicians in the early 1960s, with Curtis Mayfield, Jerry Butler and Ramsey Lewis. He was discovered by the producer Samuel Charters, and released his first album in 1965 on Prestige. The New Folk Sound of Terry Callier was an amazingly accomplished debut of sweet, yearning and blues-infused folk music. Later he moved to Chess subsidiary Cadet and made three great, but underappreciated soul-tinged albums under the guidance of Chess producer Charles Stepney, among them the standout What Color Is Love. Callier had a revival on the british soul-jazz scene of the 1990s. He was signed to Gilles Peterson's Talkin' Loud label, made six albums between 1999 and 2009, collaborating with Beth Orton, Paul Weller and Massive Attack, among others. He died of cancer at 67, in 2012

Another underappreciated folk artist with something of a renaissance later in life is Vashti Bunyan, now 78. Born in South Tyneside, England, the same year as Callier, Bunyan grew up in London, and became part of the music scene. Not comfortable with being groomed by Rolling Stones manager Andrew Loog Oldham as «the next Marianne Faithfull», she moved with her friend Donovan to the Hebrides, where she wrote the material for what was to become her debut album.

Just Another Diamond Day (1970) was an utterly beautiful collection of sweet, vulnerable folk songs that disappeared almost without a trace in the marketplace. But it was a grower. The album’s cult following grew with every reissue, and while the disillusioned Bunyan lived anonymously with her family in Scotland, first pressings of the album were among the most highly priced in the second hand market. In the early 2000s Bunyan made something of a comeback to music. In 2005, 35 years after the debut, she released her second album, Lookaftering, produced by composer Max Richter, with contributions from fans like Joanna Newsom and Devendra Banhart. Her third and final album, Heartleap, came in 2014.

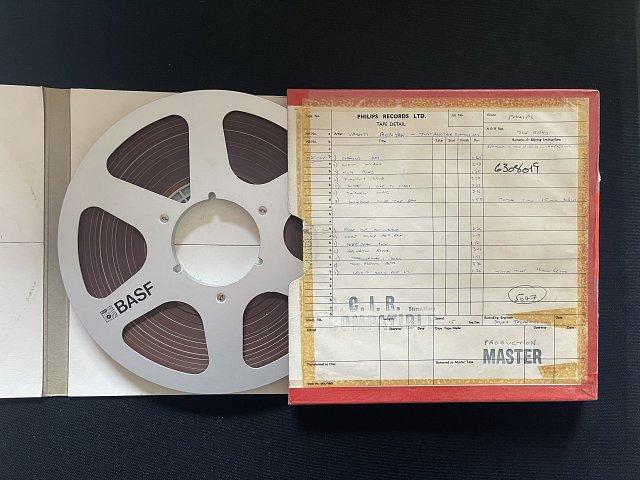

Recently, the debut albums of both Callier and Bunyan were reissued by The Electric Recording Company (ERC) in England. ERC is known for exquisitely produced and packaged, very limited and very expensive reissues of often quite rare recordings of classical music and jazz. The records are mastered and cut with no equalization or compression, on an all valve chain of vintage gear from Ortofon and Lyrec. They are pressed on Record Industry's flat profile vinyl, packaged with fanatical attention to detail in handmade covers from bespoke paper stock, set with old-fashioned brass letterpress type and printed on an old Heidelberg press.

I visited ERC’s studio and offices in London in 2015. I was mesmerized by the fabulous array of vintage gear, and impressed by founder Pete Hutchison’s fanatical perfectionism, passionate love of music and business acumen. A PDF of my story from the visit (in Norwegian, but with some great imagery) is available from ERC’s website.

I visited ERC’s studio and offices in London in 2015. I was mesmerized by the fabulous array of vintage gear, and impressed by founder Pete Hutchison’s fanatical perfectionism, passionate love of music and business acumen. A PDF of my story from the visit (in Norwegian, but with some great imagery) is available from ERC’s website.

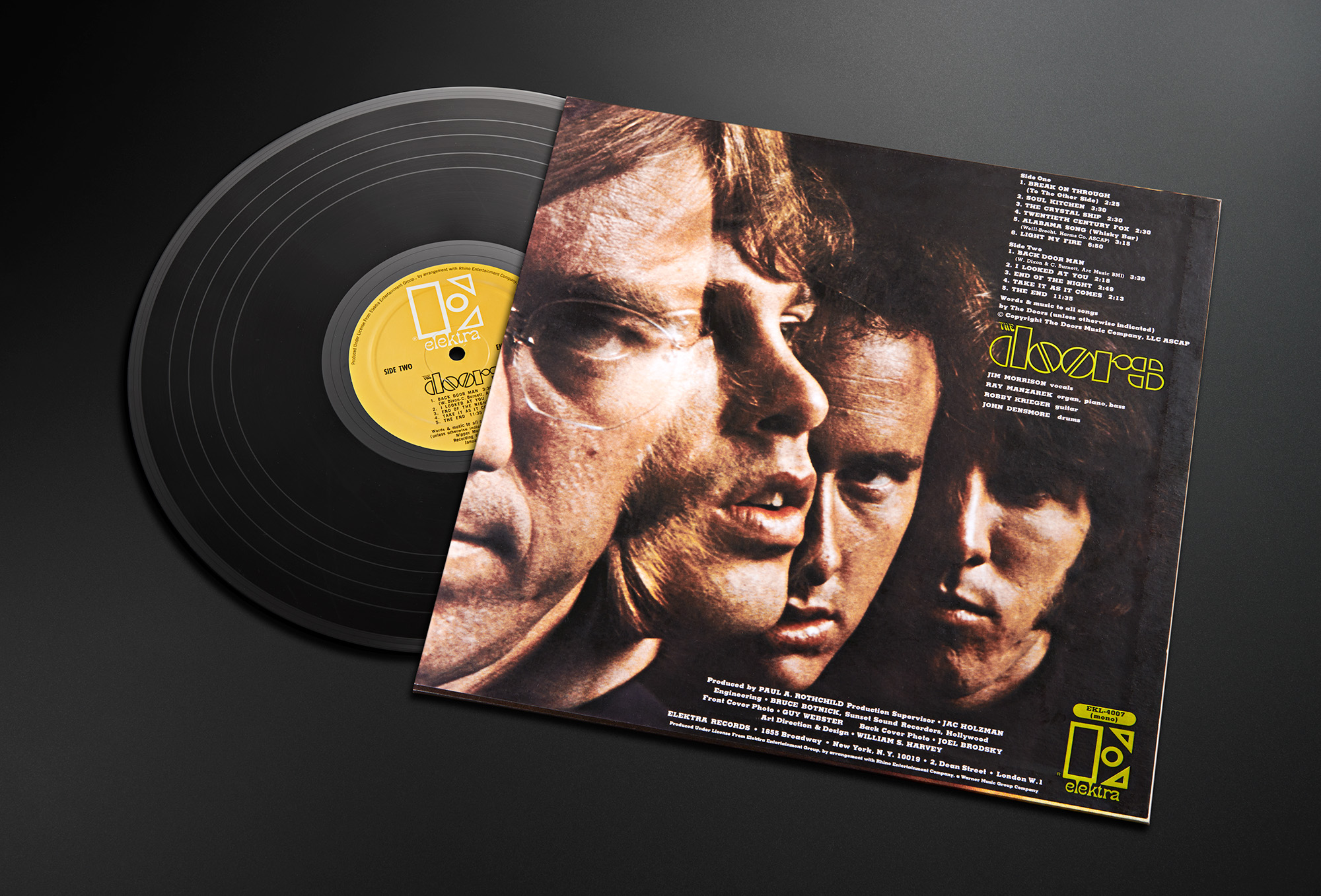

In 2020 ERC made its first foray into rock with the release of mono and stereo versions of Love’s Forever Changes. Then came the somewhat surprising 2021 release of a 20th anniversary reissue of The White Stripes’ White Blood Cells, and recently the mono version of The Doors’ eponymous debut. ERC founder Pete Hutchinson clearly has a special connection to The Doors: His other record label, the electronic music and indie specialist Peacefrog Records, is named after the song “Peace Frog” from Morrison Hotel.

***

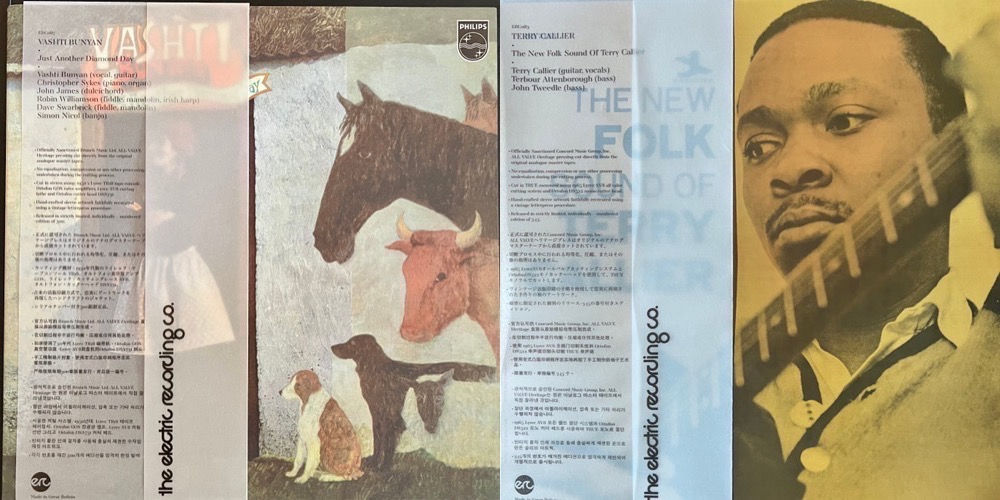

ERC is now moving into folk music, a realm of virtually unlimited potential for a label looking for deep and well recorded music with collector appeal. A mono version of The New Folk Sound of Terry Callier was released in January, a stereo cut of Bunyan’s Just Another Diamond Day in late April.

345 numbered copies of the Callier were available, 300 of the Bunyan. Both sold out immediately, as every ERC release seems to do, despite the cost. Both records sold for GBP 350 (USD 436), which means a US customer would probably end up paying around USD 500 before getting that mail call.

It is a crazy amount of money to spend on a new record. After all, perfectly decent, very good-sounding reissues of both albums are available for a tenth of the price. What some skeptics fail to appreciate, though, is that the ERC releases aren’t just reissues. They are all-out attempts at exact facsimiles or replicas of those rare and collectable original releases, down to the most minute physical detail. There might even be some truth in Hutchison’s observation to me that while the records cost fifteen times as much as normal records, they also cost fifteen times as much to make. When considering the price, one should also factor in the fact that the cheapest near mint 1970 UK original of Just Another Diamond Day currently retails on Discogs north of USD 4000 (!), while a NM Terry Callier will set you back at least USD 700.

When ERC released The Doors’ eponymous debut in mono cut from the same master tape used for the original 1967 Elektra pressing, the release received some flak ffor sounding less than stellar on certain tracks. But that is how the record sounds, warts and all. What buyers heard was what was on the tape, as delivered flat through the all tube mastering and cutting chain, not a doctored, sanitized remaster or Giles Martin-style remix. ERC’s philosophy is clearly communicated on the company's website: “... to preserve the authenticity, even idiosyncrasy, of the original masters”. In the same spirit, there are no extras, no booklets or collections of demos and outtakes with ERC releases. This non-revisionist philosophy has perhaps more in common with that of some small-scale publishers of facsimiles of very rare and collectible books, than with the rest of the retro-industrial complex of audiophile reissue labels.

While The Doors or Forever Changes might not seem the most obvious choices for the ERC treatment, Callier and Bunyan certainly do: Great music, rare and extremely expensive as originals, which haven’t been reissued a zillion times, and with master tapes therefore presumably in good condition.

While The Doors or Forever Changes might not seem the most obvious choices for the ERC treatment, Callier and Bunyan certainly do: Great music, rare and extremely expensive as originals, which haven’t been reissued a zillion times, and with master tapes therefore presumably in good condition.

Still, you might ask, why review records that are already sold out and only available at obscene prices from flippers online? It’s simple: As a music lover, record collector and audiophile, I get profound pleasure from the idea of releases like these. Someone has pulled out all the stops in making the most authentic facsimiles of great, collectible records, and getting to remove them from their exquisite packaging and listen to them is a thrill. I believe some of Tracking Angle’s readers might like to share in the experience.

The two records arrived at my doorstep protected by ERC’s new and improved, very thick, very heavy cardboard packaging, with the record held firmly within double inner packaging locked in place by thick plastic film. To get to the records themselves, you must first remove a thin layer of beautifully printed white silk paper, fastened with small plastic adhesive tabs. You could remove it carefully with a scalpel like I felt compelled to, but it’s really pointless, unless you plan to flip the record in the marketplace at some point – or you have a serious case of collector’s OCD.

The two records arrived at my doorstep protected by ERC’s new and improved, very thick, very heavy cardboard packaging, with the record held firmly within double inner packaging locked in place by thick plastic film. To get to the records themselves, you must first remove a thin layer of beautifully printed white silk paper, fastened with small plastic adhesive tabs. You could remove it carefully with a scalpel like I felt compelled to, but it’s really pointless, unless you plan to flip the record in the marketplace at some point – or you have a serious case of collector’s OCD.

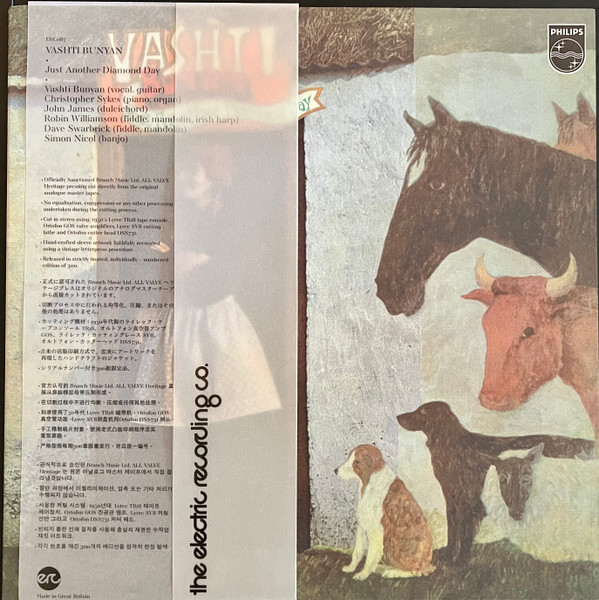

The records are protected by a thick, clear PVC cover with an embossed ERC logo. The thick tip-on style cardboard covers are adorned with a translucent Japanese style OBI strip with release info in English, Japanese, Chinese and South Korean. A card with album info and printed serial number sits under the OBI at the back. The covers themselves were physically perfect in every way on both records, with no seams splits, marks from excessive tip-on glueing or other defects.

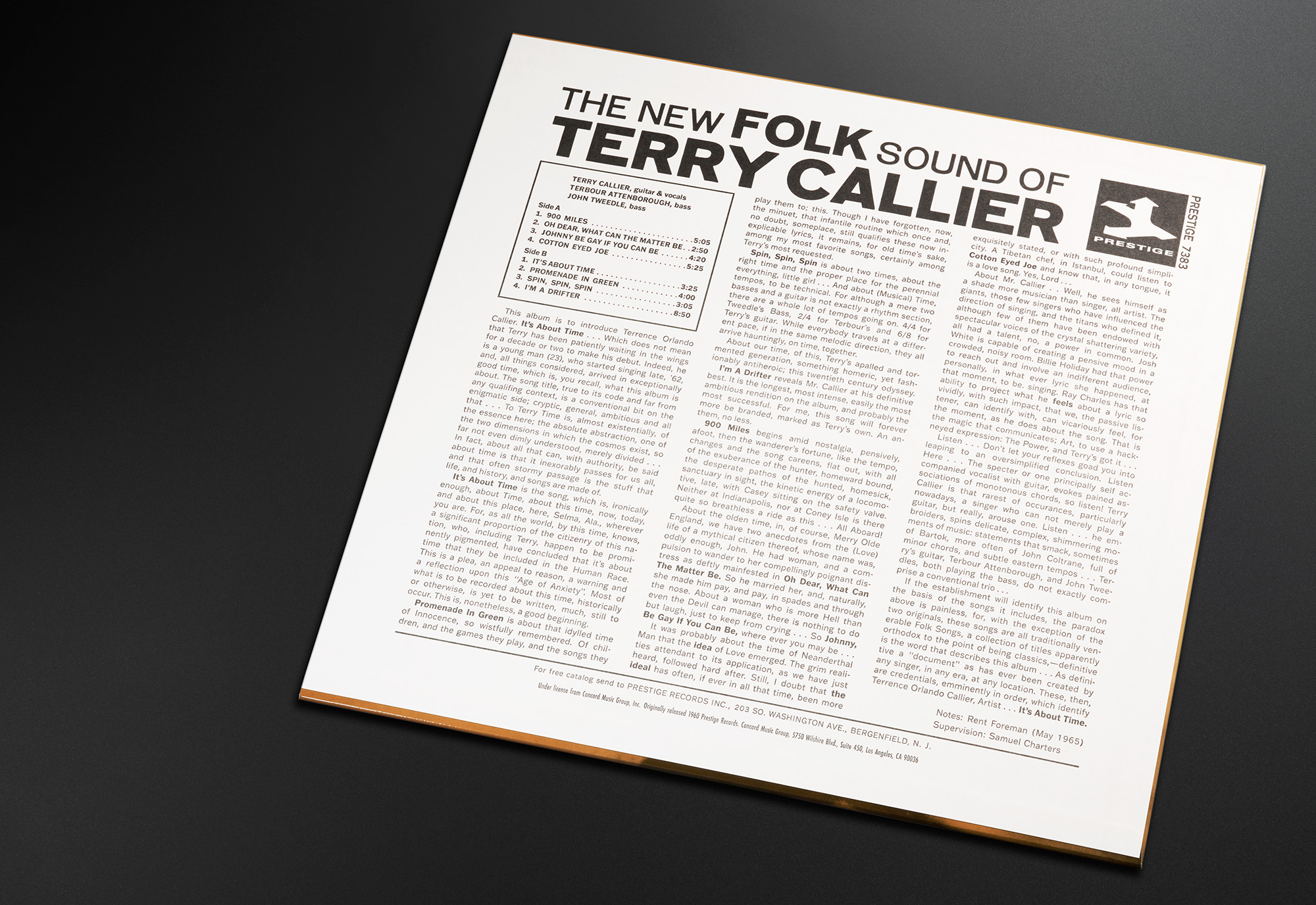

The Bunyan has a lovely, textured, matte tip-on gatefold cover, true to the original. But while the colors on my non-textured Dicristina reissue from 2004 are too warm and saturated, the ERC comes across as slightly paler and cooler in tone than how the Phillips original looks in images online. Getting colors just right clearly isn’t easy. It’s the same with Callier: Neither the ERC, with its lovely, thick, single sleeve tip-on cover, nor my Rainbo Records US reissue with its much flimsier cover, seems to match perfectly the original’s rich orange-brown duplex coloring, as shown on ERC’s own website. The ERC is a little too pale, the Rainbo far too dark orange. I much prefer the ERC, also for the fact that the cover portrait features Callier’s minor skin imperfections, which some genius have retouched off the Rainbo.

The Bunyan has a lovely, textured, matte tip-on gatefold cover, true to the original. But while the colors on my non-textured Dicristina reissue from 2004 are too warm and saturated, the ERC comes across as slightly paler and cooler in tone than how the Phillips original looks in images online. Getting colors just right clearly isn’t easy. It’s the same with Callier: Neither the ERC, with its lovely, thick, single sleeve tip-on cover, nor my Rainbo Records US reissue with its much flimsier cover, seems to match perfectly the original’s rich orange-brown duplex coloring, as shown on ERC’s own website. The ERC is a little too pale, the Rainbo far too dark orange. I much prefer the ERC, also for the fact that the cover portrait features Callier’s minor skin imperfections, which some genius have retouched off the Rainbo.

The records themselves are held in thin Nagaoka anti-static inner sleeves within a white paper sleeve. The Bunyan paper sleeve was bespoke with hand-printed identification text at the bottom, the Callier paper sleeve generic and cheaper-seeming.

Both records were perfectly flat and dead quiet, with no audible clicks or pops, save for a very light crackle at the start of side one of Callier. Both had blotches or stripes of color variation in the record surfaces, perhaps due to lacquer imperfections that have become more commonplace following the Apollo/Transco lacquer factory fire. These were purely cosmetic, however, as in completely inaudible. Still, absolute perfection should be the goal for issues like these.

Both records were perfectly flat and dead quiet, with no audible clicks or pops, save for a very light crackle at the start of side one of Callier. Both had blotches or stripes of color variation in the record surfaces, perhaps due to lacquer imperfections that have become more commonplace following the Apollo/Transco lacquer factory fire. These were purely cosmetic, however, as in completely inaudible. Still, absolute perfection should be the goal for issues like these.

***

These are excellent recordings from the golden age of analog, most likely recorded on tube gear not unlike that in ERC’s mastering and cutting chain, with great singers and virtuoso playing of acoustic instruments, captured by some of the best. Bunyan was produced by Joe Boyd, Callier by Samuel Charters, who signed him to Prestige. Unsurprisingly, both records are sonic delights.

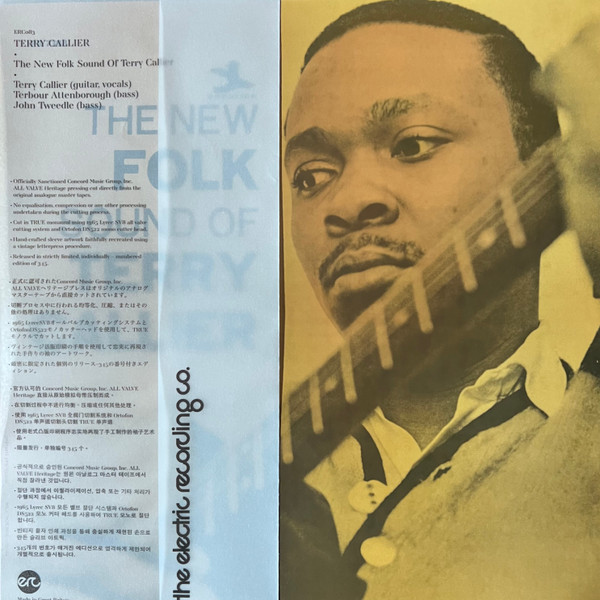

Unlike his later richly orchestrated recordings for Cadet, instrumentation on The New Folk Sound of Terry Callier is sparse and unconventional: Callier’s exquisite guitar work is supported only by two bassists, John Tweedle and Terbour Attenborough, often playing off each other in different meters on the same track. Callier got the idea from John Coltrane, who used two bassists on Olé Coltrane, Africa/Brass and Ascension, as well as on some live dates, as captured on «Live» At The Village Vanguard, with Reggie Workman and Jimmy Garrison.

The material isn't exactly Coltrane, though, but rather folk standards like “900 Miles”, “Cotton Eyed Joe” and “Oh Dear, What Can The Matter Be”. The songs may be relatively straightforward, but from the moment Callier’s voice enters dead center, I’m mesmerized by his deeply spiritual, slightly hoarse vocal style, quicksilver vibrato, and unique melodic and rhythmic phrasing.

The material isn't exactly Coltrane, though, but rather folk standards like “900 Miles”, “Cotton Eyed Joe” and “Oh Dear, What Can The Matter Be”. The songs may be relatively straightforward, but from the moment Callier’s voice enters dead center, I’m mesmerized by his deeply spiritual, slightly hoarse vocal style, quicksilver vibrato, and unique melodic and rhythmic phrasing.

Callier’s voice has been compared to many other male singers, but to me, the first reference that comes to mind is the husky, often pained voice of Nina Simone. No small compliment! Callier’s melodic guitar picking is also good, but it’s the voice, and the deep, solemn and graceful way it turns a melody, that really captures.

The record is cut in «true mono» with a single channel pathway, avoiding the smearing of sound that can happen with dual mono. The sound is excellent, rich and warm. My ten times cheaper Rainbo pressing also sounds very good, but it has more breakup, a kind of fuzzy edge, in the rendering of the vocal. It may very well have been cut from a good source, perhaps even the same source, but the mastering or cutting isn’t quite up to the task.

The record is cut in «true mono» with a single channel pathway, avoiding the smearing of sound that can happen with dual mono. The sound is excellent, rich and warm. My ten times cheaper Rainbo pressing also sounds very good, but it has more breakup, a kind of fuzzy edge, in the rendering of the vocal. It may very well have been cut from a good source, perhaps even the same source, but the mastering or cutting isn’t quite up to the task.

Callier’s foot stomping on several tracks add a grounded, low frequency pulse to the music. The low end is solid on the ERC, but even more pronounced on the Rainbo. Without access to the master tape or one of those 4000 dollar original pressings, I couldn’t say which is more correct, but given ERC’s claim that they cut without any EQ-ing, it’s reasonable to assume that the low end has been boosted slightly on the Rainbo. The latter is also cut at a substantially higher volume than the ERC, but, hey, that is what volume controls are for.

***

After returning from her quite literal horse-and-carriage journey through northernmost Britain, physically and culturally isolated from London's growing folk-rock scene, Vashti Bunyan made her first record in 1969, with American producer Joe Boyd and engineer Jerry Boys behind the glass. The London-based Boyd had produced a string of seminal albums by Pink Floyd, The Incredible String Band, Nick Drake and Fairport Convention, to mention a few. He brought in Robin Williamson (fiddle, whistle and harp) from The Incredible String Band and Dave Swarbrick (fiddle and mandolin) and Simon Nicol (banjo) from Fairport Convention to the recording session, white Robert Kirby played recorder and did string arrangements, like he had previously done for Nick Drake. Christopher Sykes played piano and organ, and John James the dulcitone. No drums or bass, you’ll notice.

Bunyan herself plays guitar, but Just Another Diamond Day is really all about her small and sweet, achingly beautiful, almost bell-like voice – all fragility and quiet determination – and a collection of songs written by her alone or with writing partners. Bunyan meditates on life, love, nature and the choices we make. The songs are very English, very much in the melancholy folk ballad tradition. Although not as memorable as the compositions of contemporaries like say, Joni Mitchell or Judee Sill, they make for a very moving whole. The fact that Bunyan's isolation in the north had made her miss the folk rock of Fairport Convention and others, is perhaps one of the reasons the albums sounds more timeless than some others from the period, and comes across as almost otherworldly in its quiet beauty..

Bunyan herself plays guitar, but Just Another Diamond Day is really all about her small and sweet, achingly beautiful, almost bell-like voice – all fragility and quiet determination – and a collection of songs written by her alone or with writing partners. Bunyan meditates on life, love, nature and the choices we make. The songs are very English, very much in the melancholy folk ballad tradition. Although not as memorable as the compositions of contemporaries like say, Joni Mitchell or Judee Sill, they make for a very moving whole. The fact that Bunyan's isolation in the north had made her miss the folk rock of Fairport Convention and others, is perhaps one of the reasons the albums sounds more timeless than some others from the period, and comes across as almost otherworldly in its quiet beauty..

The record wasn't released until 1970, after Boyd licensed it to Phillips. Is sold almost nothing at the time, but then, nor did Nick Drake.

You’d really have to mess up to make recording sound bad. The ERC sounds utterly wonderful. My 2004 Dicristina pressing is cut louder than the ERC, but sounds almost as good, with no harshness in the rendering of Bunyan’s fragile voice. There is more groove noise on the Dicristina, though, a testament to the quality of ERC’s cutting and Record Industry-pressed vinyl. Somehow, the ERC just sounds more right, as it should.

You’d really have to mess up to make recording sound bad. The ERC sounds utterly wonderful. My 2004 Dicristina pressing is cut louder than the ERC, but sounds almost as good, with no harshness in the rendering of Bunyan’s fragile voice. There is more groove noise on the Dicristina, though, a testament to the quality of ERC’s cutting and Record Industry-pressed vinyl. Somehow, the ERC just sounds more right, as it should.

A double triumph, for the lucky few.

.png)