Frank Sinatra’s “In the Wee Small Hours of the Morning”

The Voice's First Masterpiece in a New Form for a New Medium

Frank Sinatra’s In the Wee Small Hours of the Morning is a landmark recording in his life and career, in his growth as an artist, and in the history of popular music and jazz. His ninth album, the third for his then-new label Capitol records, and his first fully realized “Concept” album, all but one of its sixteen songs were recorded in five sessions from February to April of 1954.

Released the following year, it was a huge critical and popular success, and both its esteem and its popularity have only risen in the seven decades since, its standing as a classic solid as Gibraltar’s rock, more than a few Sinatra enthusiasts regarding it as both his best album and one of the greatest vocal albums ever recorded. If timing really is everything, that it happened at all owes in no small part to a serendipitous convergence of factors and circumstances from the intimately personal to the internationally public.

Eliminate any one of them, shift one or more in time, or add new ones, we would surely have a different album but it’s unlikely we would have had this one, and that would be a pitiable loss. What makes it so special?

As I want to address this question in artistic terms, I refer readers who wish to know more about the history of the Concept album, including the circumstances that led up to this one, to my Tracking Angle review of Impex’s Sing and Dance with Frank Sinatra (in which I detail the five-year slump to the bottom in Sinatra’s career and fortunes between1947 and 1952.

The Album

Sinatra was officially signed by Capitol Records on April Fool’s Day of 1953. If the years leading up to that day, most of 1951 in particular, bore witness to the decline in his fortunes and popularity, he was, professionally speaking, not only far from inactive but in fact did quite a lot of good and some great work, including six albums for Columbia, the last of which, Sing and Dance with Frank Sinatra, recorded over several months spanning mid-1949 to early 1950, was released in October of that year. Its sales were weak, it never placed on Billboard’s charts, but it was an artistic and a personal triumph. Known for ballad singing, Sinatra wanted to demonstrate that he could swing, which he did on this album as if to the manner born, such that in the decades since it has come to be recognized as one of his best.

Better still in terms of his rehabilitation as a superstar adored by millions is that he managed to land the role of the sympathetic Maggio in the movie version of James Jones’s novel From Here to Eternity, one of the most prestigious films of 1953, garnering thirteen, winning eight Oscar nominations, Sinatra himself taking home the statue for Best Supporting Actor. Mitch Miller believed that the singer’s virtually over-night redemption was occasioned by the spectacle of Sinatra as Maggio suffering at the hands of the sadistic bully Fatso, eventually dying as the result of corporal punishment. This was apparently penance enough for his audiences to forgive behavior they had found deplorable only a year or two earlier: principally the very public affair with Ava Gardner that humiliated his wife Nancy, not to mention the two of their three children old enough to know what was going on, and led to divorce.

Fatso and Maggio, villain and victim, in From Here to Eternity

Fatso and Maggio, villain and victim, in From Here to Eternity

Capitol wasted no time getting their new hire into the studio. By the end of 1953 Sinatra had laid down eight numbers, enough to fill his first album for the new label: Songs for Young Lovers, released in January 1949 as a 10-inch LP. In April of the same year he recorded eight moderately uptempo songs for another 10-inch LP called Swing Easy in time for an August release. Both albums generated brisk sales, charted on Billboard, stayed there a good while, and remain today among his most popular and critically acclaimed recordings. Those who were paying serious attention to the music found these albums revealed a “new” Sinatra: the voice darker, deeper, a bit rougher,[1] the persona behind the voice by turns more intimate and vulnerable or more confident and assertive, with an easy self-assurance and an appealing swagger that suggested an artist who no longer felt he had to prove anything to anybody.

Also in evidence are a new-found nuance, suppleness, and elasticity in the phrasing, an even more exquisite touch and attention to inflection and dynamics in his “readings” of the lyrics, and a correspondingly greater sensitivity and deeper depth of feeling to the expressiveness. What Sinatra brought to the Great American Songbook was the prime importance he placed upon the meaning of the lyrics. From the outset of his career, his conviction in the worth of the songs he selected, his sincerity in how he sang them, and the authenticity of emotion he found in or brought to them were absolute, vindicating his claim years later that whatever “else has been said about me personally is unimportant. When I sing, I believe I'm honest."

At work in the studio, the perfectionist who no longer had to prove anything to anybody

At work in the studio, the perfectionist who no longer had to prove anything to anybody

Those who were listening seriously also sensed something different about these two albums: each had its own highly individual mood, attitude, or style—its own concept, if you will. Neither was just a "collection" of songs, instead, the songs related to one another. Sinatra was not musically trained, but he loved classical music, was highly knowledgeable about it, and had an extensive recorded collection and pretty sophisticated tastes (Ralph Vaughan Williams evidently his favorite composer). Sinatra obviously noticed that the great classical composers did not compose individual songs only, they also wrote song cycles in which each individual song is part of a whole and derives its fullest meanings from the whole. It seems clear, at least in retrospect, that what Sinatra was looking for was something that would link yet extend beyond each individual song, an overall organizing principal that would enable him to create an aggregate form which in turn would imbue each song with a deeper range of meaning and significance than the song itself was capable of on its own.

In those days almost no composers of popular music did anything like this unless it was in musicals, and almost nobody made albums where the material was selected with the intelligence and care of Sinatra’s first two Capitols. In other words, as popular music had no equivalent to the song cycle, grouping together a number of different songs with related themes and subjects that would both vary and reinforce the overall concept was Sinatra's way of giving himself the longer forms he was seeking. Even better, he could order the songs in such a way as to tell longer, bigger, more complex, exciting, entertaining, and moving stories.The Concept album was his avenue toward creating those forms.[2]

Young Lovers and Swing Easy constitute the beginnings of the Frank Sinatra Concept albums. Beautiful as they are, great as they are, however, they’re not quite fully there. Their Concepts are a little too generalized or insufficiently defined: “young lovers” and “swing easy” are more like categories than concepts. Indeed, Swing Easy! is hardly a concept at all—which even the cover, Sinatra with arms outstretched, a big smile on his face, singing against a blank background, tacitly admits—rather, a generic type of lightly swinging, moderately up-tempo songs Sinatra dispatches with consummate musicianship. The songs themselves, mind you, are superb, it's the concept that's diffuse.

Songs for Young Lovers does have a concept, and again the cover art provides the clue, the first of Sinatra’s signature street-light-at-night paintings with the singer leaning against the lamppost, a pair of lovers behind him, another in front. Yet the theme reveals itself fully only in the listening. It’s a celebration of young love in many forms, but the first song, Rodgers and Hart’s magnificent “My Funny Valentine,” immediately suggests “young” is open to more than one meaning, referencing lovers who are young in age and/or also lovers who are older whose love hasn’t diminished with age. “Violets for Your Furs,” said to be based on one of Sinatra’s many lovers, Lana Turner, who liked to wear flowers on her furs, is “nothing” more than a song about a swanky night on the town with two persons in the prime of their romance, which means, especially in the context of all the other songs, that it is about some things that matter very much. “I Get a Kick Out of You” is a mock lament by the lover that any and every other pleasure in life pales beside the “fabulous face” of his beloved.

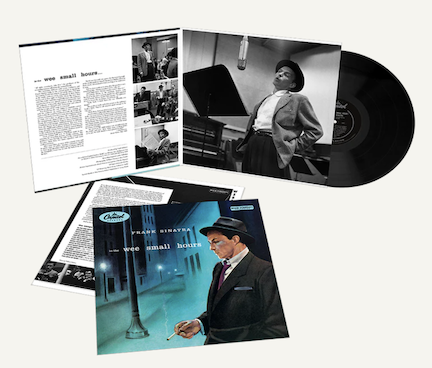

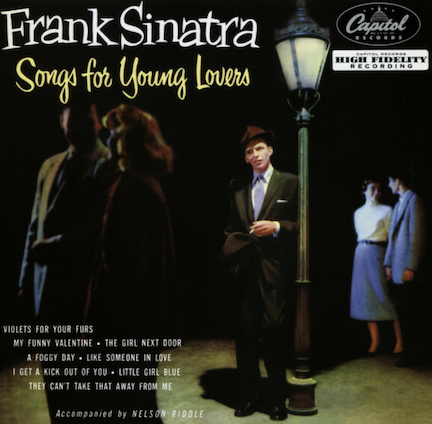

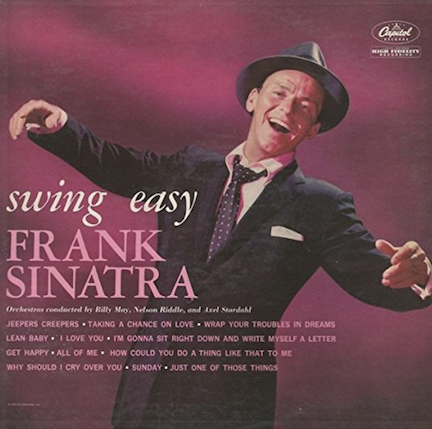

First two albums for Capitol: Concepts in the making

First two albums for Capitol: Concepts in the making

Sinatra himself knew where he wanted to go with his Concept albums: a greater range of emotion and feeling, a more complex and probing psychological penetration, a more exciting and sophisticated display of rhythm, drive, and energy in the swinging albums. But he couldn’t get there by himself. What he needed was a colleague, a fellow traveler, a co-creator. He already had one in his pianist Bill Miller, whom he always relied upon for advice when conceiving a concept and selecting appropriate songs. But he also needed someone who could handle all the other music and musicians, the instrumentalists and the arrangements, that go into a vocal album. He needed someone who could write charts as bold, thoughtful, and innovative as he himself was when he sang—he needed a match in musical artistry. In other words, he needed Nelson Riddle.

Nelson Riddle, the co-creator

Nelson Riddle, the co-creator

Born six years apart (the singer first) and raised hardly twenty miles from each other in northeastern New Jersey, Sinatra and Riddle did not know and were initially wary of one another. Alan Livingston, the Capitol executive who had both the courage and the good sense to sign Sinatra—this a year after the powerful agent Irving “Swifty” Lazar pronounced the singer “a dead man”—believed Riddle was the man for Sinatra and cannily engaged him as a conductor for Young Lovers. Only one chart was written by Riddle himself; Sinatra, who rarely missed anything musically, knew it was interestingly different from the rest, liked it, asked who wrote it, and when told it was Riddle, complimented him. But Riddle wasn’t in quite yet.

Although not famous at the time, the arranger was far from unknown. Inside the business he had acquired perhaps the best reputation a freelance arranger could want: able to work exceedingly well at very high levels of craft and artistry, and fast. In the forties he had done some arrangements that impressed Tommy Dorsey and Glenn Miller; Doris Day’s 1949 hit “Again” was a Riddle chart; the next year he was writing for Nat King Cole. Soon he was Capitol’s go-to man because he could work under tremendous pressure turning out quality charts faster usually better than anyone else's.

Like a lot of star vocalists, Sinatra already had arrangers and instrumentalists he liked to work with and trusted. But he also knew in his bones that he couldn’t go on doing what he had done in the previous decade, that he had to move beyond the ballads and what Will Friedwald, in his seminal critical study Sinatra: The Song Is You! A Singer’s Art, called the “comfort food” of Axel Stordahl’s plush arrangements. Sinatra never placed his trust easily and he always required proof before he did. Riddle was the same way, though unlike Sinatra he was by nature shy, even diffident, and not very assertive.[3]

Charles L. Granata in his indispensable Sessions with Sinatra: Frank Sinatra and the Art of Recording, tells a story that reveals much about both men. One early session had hardly begun before Sinatra called a break and beckoned Riddle for a meeting outside the studio. Milt Bernhart, the great trombonist on “I’ve Got You Under My Skin,” followed them into a hallway where he could see but not hear them through a soundproof glass window in a smaller studio. “Nelson was standing frozen,” Bernhart recalled, “and Frank was doing all the talking. His hands were moving but he was not angry . . . . He was gesticulating, his hands going up and down, and sideways. He was describing music and singing!” When they came back and Sinatra dismissed the session, Bernhart was certain he knew the problem was that Riddle’s arrangement was so busy it left no room for the singer: “Frank was giving him a lesson: a lesson in writing for a singer. A lesson in writing for Sinatra.”

This was no trace of ego on Sinatra’s part. If the charts are so busy they cover or otherwise fight with the singing, it means they’re covering the lyrics too, forever and always a no-no with this singer. Sinatra required a care, an attention to detail, an ability to switch or modulate tempo, dynamics, and instrumentation gradually or on a dime, and equally an ability to work around the singer, filling in the spaces when he wasn’t singing. Riddle proved a rapid study. Many years after this incident, he said that he stuck to two rules for Sinatra: “First, find the peak of the song and build the whole arrangement to that peak, pacing it as he paces himself vocally. Second, when he’s moving, get the hell out of the way. After all, what arranger in the world would try to fight against Sinatra’s voice? Give the singer room to breathe. When the singer rests, then there’s a chance to write a fill that might be heard.”[4]

Although the two were very different in personality and temperament, they were both psychologically complicated men. Up to this point in his career, Riddle hadn’t had much opportunity to write charts for anybody like this, though he clearly wanted to. Friedwald, whose book is the best book I know about the relationship between singers and their arrangers, writes that before Sinatra, Riddle had everything except a style. Before Riddle, Sinatra had style to burn, but only with Riddle did he find a talent commensurate with his ambitions to strike out on a new path, one that required not just an amanuensis but a collaborator, a real co-creator in the fullest sense.

Collage of singer and arranger at work in the studio

Collage of singer and arranger at work in the studio

So with his third album for Capitol looming, a sympathetic label, the right arranger, and first-class technicians and facilities, Sinatra was already beginning to conceive the concept, select the songs, and think about how they might be ordered. Only one more matter had to be attended to. The LP became a commercial reality in 1948, and from the beginning LPs came in three sizes: 12-, 10-, and 7-inch diameter. The last was for singles, the first for classical music with its longer compositions, the middle for popular music. Keep in mind that until the early fifties, about half the records sold were still 78-rpm. Owing to a number of things—not least, I’d guess, because he was, after all, Frank Sinatra and because all the indicators were that the 7-inch disc would remain for singles while the 12-inch disc, which in those days could accommodate about 25 minutes of music per side, would soon displace the middle size for all music—Capitol made the decision to release In the Wee Small Hours in two formats: a pair of 10-inch sides with four songs per side and a 12-inch with eight songs per side, the first pop album anywhere to get the deluxe 12-inch treatment.[5] Finally, Sinatra would have a Concept album of sufficient duration to allow him to realize the longer, richer, more substantial form he had been working toward. I do not think it in the least pretentious to say that the principal thing which differentiates In the Wee Small Hours of the Morning from previous Concept-like albums is that it embodies a concept that is also a genuine artistic vision.

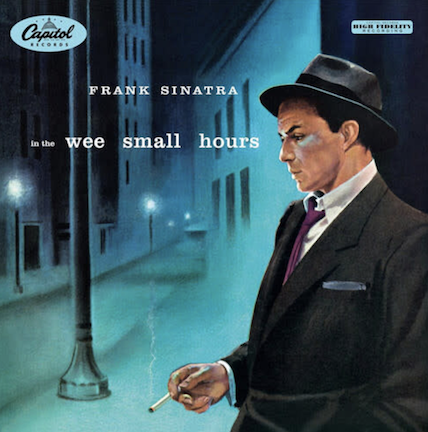

Once more, the cover art adumbrates the music within, only this time the painting is far more precisely expressive: the lamppost at night is back, Sinatra leaning against it, completely alone this time, while behind him recedes a city street so empty and desolate it could have come out of a Bergman movie. The title song, which opens the album, is the very model of the kind of focus the less well-defined titles lack: a man lies in bed at that time of night when it is darkest before the dawn, wide awake hoping the woman who has just left him will call, yet knowing she won’t because the relationship, be it romance, affair, or marriage, is finished and she’s moved on. The title recalls the chilling sentence from Fitzgerald’s The Crack-Up: “In a real dark night of the soul it is always three o'clock in the morning, day after day.” The point of view is that of the person who has been rejected and left behind, here the man. The mood throughout is sad, melancholic, and lonely.

The first Concept album to embody a real vision

The first Concept album to embody a real vision

The sixteen songs happen to fall into two groups of eight that could be conveniently divided between the two sides, something I like to believe was intentional rather merely adventitious. After the title song sets the scene and the next one the mood—“Mood Indigo,” a hue literally so blue the singer “could cry”—the remaining six are confined to the immediate aftermath of the breakup. “In “Glad to be Unhappy,” the singer’s sadness makes him glad because it keeps him emotionally tied to her. In “I Get Along without You Very Well,” the irony is pure, i.e., he doesn’t get along without her very well, indeed at all, and there’s hardly anything he can think about that doesn’t remind him of her. In “Deep in a Dream,” he finally falls asleep but his dreams are filled with her, echoing the previous song and anticipating the next one, “I See Your Face Before Me,” where she now dominates his daydreams as much as those at night. “Can’t We Be Friends?” extends the dream motif, the woman now the girl of his dreams who destroys them by asking him, in that unkindest cut of all, to be a friend. “When Your Lover Has Gone” concludes the first set leaving the singer in fairly abject solitude.

In my view these first eight songs inscribe a narrative progression and a tight-knitted integration of structure and dramatic build (it almost shapes itself into a plot) that are never surpassed in any of Sinatra’s subsequent Concept albums and are rivalled only by Only the Lonely and maybe September of my Years, a Reprise release. They could almost stand on their own as a self-contained song cycle—except for side two, which provides a larger, grimmer context. The eight songs there are less tightly knit, but this is because they range wider, some of them casting their gaze far into the future. “What Is This Thing Called Love?” strikes an almost philosophical note in the way it moves beyond the lost individual love to question the very nature of love itself. “Last Night When We Were Young” appears to take place a long while after the breakup, yet so vivid are the memories they might as well have happened yesterday. In “I’ll Be Around,” another song set a good while down the road, the singer, in what is surely meant to be imaginary conversations with the woman, assures her he’ll be there whenever her latest affair ends, of which there have apparently been several. “I’ll Never Be the Same” recognizes that the pain of unrequited love, this particular love, anyhow, will never go completely away, while the last song, “This Love of Mine,” suggests he will never fall out of love with her: “this love of mine goes on and on . . . .“ In the second verse the line “it’s lonesome through the day/but oh the night” is a fleeting reference to where the cycle began in the wee small hours of morning. It’s a not full-circle return, however: there he was still hoping she’d call, but now that’s all over and what he’s left with is the pain that, like his love, will never go completely away.

Years later Riddle confessed that he never cared for Sinatra’s younger voice. “I thought it was far too syrupy. I prefer to hear the rather angular person come through. To me his voice only became interesting during the time when I started to work with him.” But Riddle never attributed the change to his influence, instead to the breakup of Frank’s tempestuous marriage to Ava, which stretched through and beyond the recording of the album and brought him near to suicide. This is one instance of that confluence of circumstances I alluded to at the outset which fed into the album. From this perspective, In the Wee Small Hours of the Morning is maybe the best collection of songs ever assembled about what it feels like to be dumped by someone you’ve fallen hard and hopelessly for. (I can’t think of another that comes close.) But it is more: the first masterpiece in a new musical form invented specifically for the new medium of the 12-inch long-playing vinyl record. A group of previously unrelated songs, many of them mini-masterpieces in themselves, has been collected, organized, and performed such that they create a wholly new work of musical art that can be fully experienced only through the medium for which it was created.

As a Concept album In the Wee Small Hours of the Morning is in any practical sense perfect, yet there’s a curious dichotomy in it that I’ve never been able to account for, a dichotomy, I hasten to add, that I believe is intentional yet that not for a moment undermines the perfection: despite the prevailing mood of melancholy, sadness, and heartbreak, the overall effect is not devastation—that wouldn’t come until Only the Lonely. Instead, it’s thoughtful, ruminative, contemplative, rather bittersweet, and not entirely bereft of humor, usually tinged with gentle irony (e.g., from “Glad to Be Unhappy”: “Unrequited love’s a bore/And I’ve got it pretty bad./But for someone you adore/It’s a pleasure to be sad”).

One reason for this dichotomy is obvious. Despite the fact that some of the songs lend themselves to belting, melodrama, and self-pity, Sinatra steadfastly resists any such temptations in those directions. In this he was aided, supported, and partnered every step of the way by his new collaborator with orchestrations applied with lightest, purest, sparest, most precise and delicate of touches. I don’t believe there’s cut on the album where Riddle deploys the full complement of players at his disposal.

So, yes, it’s easy to explain how Sinatra and Riddle realized this dichotomy, but it wasn’t until I read Will Friedwald that I understood the why of it. “Musically speaking,” he writes, “In the Wee Small Hours was about closure, saying goodbye, farewell, an amen to the dire nosedive period of the early 1950s” and it paved the way for “the real, full-length statement of rebirth” that became Songs for Swingin’ Lovers!, which “opened with the ultimate song about fresh beginnings”: “You Make Me Feel So Young”. Giving expression to heartbreak in Wee Small Hours was a necessary step, a liberating one, in Sinatra’s psychic rehabilitation that made possible the string of Concept masterpieces which followed.

One thing more and not unrelated: Sinatra was always a personal singer, but starting with Wee Small Hours, he became a personal singer in far more intense and interior way. The album was so fueled and fired by his dissolving marriage to Gardner that he often referred to it as his “Ava” album. In fact, it was only the first of several Ava albums. Once they were divorced in 1957 they stayed in touch with each other the rest of their lives—"friends" doesn't quite seem le mot juste here for a couple as destructively enmeshed as they in each other issues and problems—and even carried on the occasional sexual assignation despite being involved with or married to others. Frank's singing on Wee Small Hours, Close to You, and Only the Lonely goes beyond personal singing virtually into private singing, the crowning irony for him and Ava being that their privacy, even at it most intimate, was so often played out in public, writ large the world over by a mass media that chased after them like The Furies.

Riddle was far from alone in believing the breakup of Frank's marriage to Ava brought a new depth to his singing.

Riddle was far from alone in believing the breakup of Frank's marriage to Ava brought a new depth to his singing.

The Tone Poet Remastering

I have a copy of almost every version of In the Wee Small Hours released in every period since it first appeared in 1954, though I acquired them out of chronological order. The first I heard was the one in the big vinyl box remastered by Mobile Fidelity, released in the early eighties. Sonically this was a big disappointment. Of course, the recording is mono, no problem there, but while very clean, clear, and pressed on quality vinyl, it sounds almost antiseptically scrubbed, suffering from the same issues so many Mo-Fis did back then: clean but lean, thin, bright, edgy. The next one I acquired was the joint Capitol-Reprise Entertainer of the Century series of digital remasterings in the late nineties, released on Redbook CD. In the area of tonal balance these are actually a big improvement over MoFi: smooth, warm, inviting, rounded, and entirely free from hiss despite the mid-fifties provenance of the recordings. Something still didn’t seem quite right about them, but I dismissed that because the tonality was so much more to my liking than Mo-Fi’s.

Several years later I acquired a vintage vinyl copy from a fellow who was divesting himself of LPs he no longer listened to much, including a few Capitol Sinatras. What a difference. Yes, the hiss was back, the surfaces, though acceptable, hardly pristine, but my goodness, all of a sudden there was a more tactile presence, a rounded dimensionality to the voice, the instruments more truthful in timbre. I don’t want to overstate this: these CDs (now out of print but readily available) are good enough, but the penalty for the elimination of hiss and all that smoothening was to rob a good bit of the life, vitality, and vividness from the musicmaking, so wonderfully present on the vintage vinyl. Capitol’s recordings of voices, Sinatra’s especially, are always splendidly alive.

Now, freshly remastered for Blue Note's Tone Poet Audiophile Vinyl Reissue Series, it sounds that way again. “Every aspect of these Tone Poet releases is done to the highest possible standard,” says the promotional literature. “It means that you will never find a superior version. This is IT.” This is not hyperbole. The Tone Poet version is superior to the Mo-Fi by a huge margin, to the Entertainer of the Century CD by a less but still significant margin. As for the vintage LP, the margin narrows considerably but it’s readily audible, not least for the quality of the surfaces, which are outstandingly quiet. The remastering was done by Tone Poet’s usual crew, Joe Harley the dedicated producer, the always reliable Kevin Grey of Cohearent Audio, the 180-gram vinyl pressing by Record Technology Inc. Transparency, tonal balance, and dynamic range—surprisingly wide for a program that is pretty lyrical and relatively subdued— all come up sounding better than ever. But it’s in the areas of color, richness of texture, and that difficult-to-define organic character of analog and vinyl where this new remastering really shines. Shines is the operative word, not as in audiophile brilliant, rather in the burnished glow of a warmth and vibrancy that diverts attention away from the technology and toward the music.

This entry in the Tone Poet’s series is unusual in one respect. According to the producer Joe Harley, Capitol routinely “ran two parallel, identical decks at that time. I believe they were Ampex 200s. So, it wouldn’t be correct to call one or the other, a ‘safety back up’, which could be interpreted to be a dub. In fact, they both got the same input signal and at the same time.” In other words, the tapes Grey worked from were not the masters used for all previous releases, rather from the identical parallel masters which differ only in their hardly ever having been played. Harley told me he and Grey also did “some very slight tweaking on the low end and upper-mids. In the case of Sinatra, we let his voice be the guide and went from there. The EQ difference was subtle, but when we would A/B, it was clear we were on the right track.”

In the absence of any other explanations, this probably accounts for the impression of greater transparency, dynamic range, openness, and lifelike presence, plus fractionally more air and room presence around and among Sinatra and the players. There’s also better definition across the frequency range, notably at the bottom, which is a bit more prominent. When I mentioned the transparency to Harley, he attributed it to “Kevin’s unbelievably transparent chain, along with, of course, what is on the original master. Kevin's chain better allows you to hear what is on the master tape.”

Harley informed me that the first run of Wee Small Hours is almost completely sold out, though it's still available from the usual sources as of this posting (Elusive Disc, Acoustic Sounds, Amazon, etc.), so do not tarry if you want one (another run will soon follow). In the meantime, since the Tone Poet’s vinyl series has consisted mostly in instrumental jazz, I asked Harley if there were plans for any more Sinatras. His reply was a tantalizing, “There will be more, but I'd rather not get into specifics at present. I think you will be pleased.” I’d pay a lot of money for a complete set of the fifteen original studio albums Sinatra recorded for Capitol.[6] Speaking of money, the new album radiates class all the way: gatefold presentation, good notes, vintage photographs, nice sturdy stock for the jacket, beautifully reproduced original cover, pristine 180-gram vinyl all for the princely sum of $38.98. Gentlemen, in these days of rising prices all around you deserve a hearty thanks from us all.[7]

[1] This newly acquired depth and power he puts to impressive use on the side two opener, Porter’s “What Is This Thing Called Love?”

[2] In the sixties and thereafter many pop, folk, jazz, and rock singers began to build albums around concepts (the most obvious example being the Beatles’s Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band). But all this was in the wake of Sinatra’s Capitol and Reprise Concept albums. During the Reprise years Sinatra himself pursued longer musical forms by actually commissioning them, starting in 1969 with A Man Alone, a whole album of songs written for him by Rod McKuen on the subject of loneliness. The next year brought Watertown: A Love Story, a through-conceived narrative cycle by Bob Gaudio and Jake Holmes, who hailed from the world of pop-rock, about a man in a small town whose wife leaves him for the big city, taking their sons with her. Despite the considerable disagreement these two albums still generate among the Sinatra cognoscenti, they demonstrate seriousness of purpose and some merit. But 1980’s three-LP box Trilogy: Past, Present, Future, a kind of musical autobiography of Sinatra himself, is another matter entirely. Parts one and two consist entirely in songs Sinatra recorded early and later in his career and are good (though without displacing earlier recordings). But “The Future,” a suite of new songs that contain some pretty self-aggrandizing, not to say risible, mythmaking (among its six sections is one where Sinatra takes us to several planets in a spaceship, a musically galactic tour unlikely to disturb the peace in which Gustav Holst no doubt rests), is unique in having almost nobody who likes it. Even Sinatra’s best critic Will Friedwald, who usually finds something good to say about any Sinatra endeavor, finds that this third disc “almost resists description,” which he does not mean as a compliment.

[3] “There’s only one person in this world I’m afraid of,” Riddle once said. “Not physically—but afraid of nonetheless. It’s Frank, because you can’t tell what he’s going to do. One minute he’ll be fine, but he can change very fast.”

[4] Any song on Wee Small Hours will demonstrate this in abundance but start with the lovely trumpet solo Riddle writes for Sweets Edison over the bridge in “Ill Wind,” or the way he weaves his signature flutes in, out, and around the vocals in “Glad to Be Unhappy.” Like Sinatra, Riddle also loved classical music and studied it assiduously, though his special loves were Debussy and Ravel (to whom he is frequently, and justly, compared as an absolute master of orchestration).

[5] Later Capitol combined Songs for Young Lovers and Swing Easy! onto a single 12-inch release, two different eight-song Concepts on one album.

[6] The number of albums Sinatra made at Capitol varies depending on whether you count, in addition to the studio albums, compilations (mostly of singles), and Tone Poems of Color, the collection of instrumental pieces by Alec Wilder Sinatra conducted. My sixteen figure includes all the original studio albums plus the Wilder pieces, but none of the compilations.

[7] A warning: Amazon and some other venues offer a so-called “Deluxe Edition” of In the Wee Small Hours of the Morning in vinyl selling for $34. Do not buy. Some shady European companies pirate recordings and market them in vinyl. The provenance of the sources is anybody’s guess, but they’re definitely not from the original label. Avoid like the plague. This warning does not, however, apply to Capitol’s own vinyl reissues, e.g., the label’s 2018 60th Anniversary Stereo Mix Deluxe of Only the Lonely is the best remastering of this great album I’ve ever heard, with the companion CD issued simultaneously its near equal. The print run of the vinyl was limited but new copies can still be ordered from Amazon and other sites; the companion CD remains in print.

.png)