More Stellar Shostakovich from Boston: Yo-Yo Ma Digs Deep and also Takes Off in the ‘Cello Concertos

Another outstanding recording from Producer/Engineer Shawn Murphy helps stick the landing

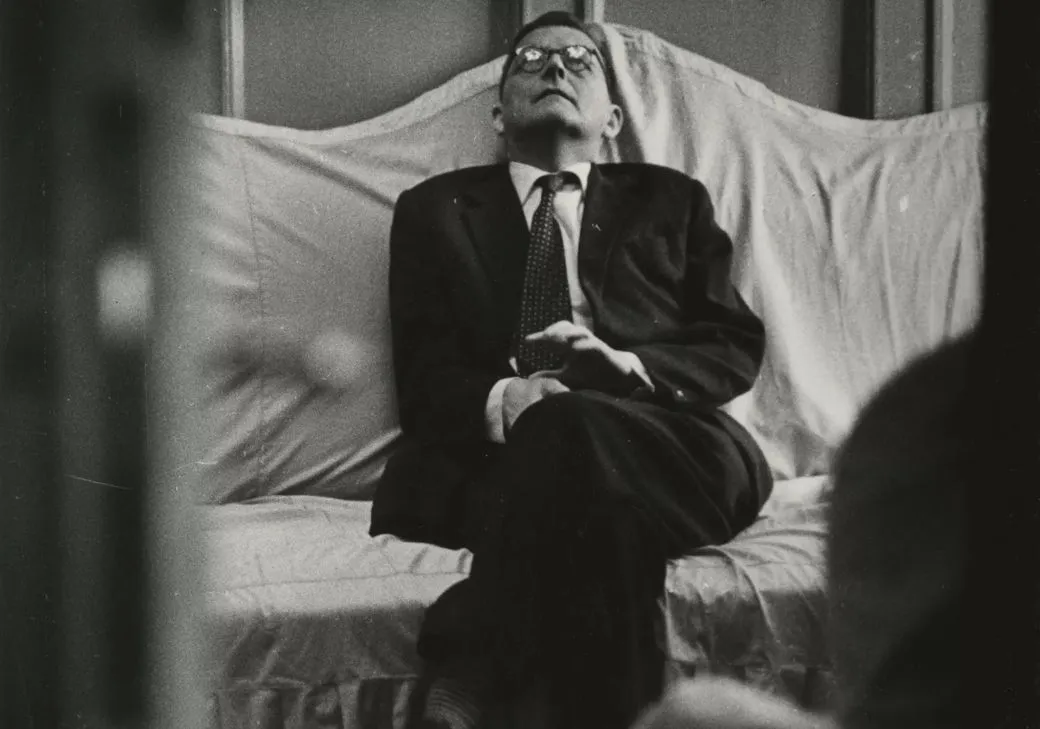

Dmitri Shostakovich in 1958, the year before he composed the First 'Cello Concerto (Lev Ivanov)

Dmitri Shostakovich in 1958, the year before he composed the First 'Cello Concerto (Lev Ivanov)

In all honesty, I was a little trepidatious about dropping the needle on this companion record to the Shostakovich Piano Concertos with Yuja Wang that the same conductor and orchestra gave us recently, recorded to be part of Andris Nelsons “cycle” of Shostakovich’s symphonies, concertos and opera “Lady Macbeth of Msensk” - now all gathered together in a CD box set.

I gave that LP a rave review, and my enthusiasm was catching. In his review of the Supatrac Nighthawk arm, our esteemed editor wrote the following:

“I wish Mark could hear what this arm does with it. So delicate, so precise, so powerful and free of mechanical artifacts. The bass is "so rich and vast" and whoever cut this to lacquer did a superb job.

“Had digital recordings sounded like this in the 1980s, I think everyone reading this would have been on board. In addition to perfectly tracking the piano, the arm's imaging and soundstaging stability produced a vivid, three-dimensional picture well into the depths of the "shoebox" Boston Symphony Hall.”

I wish I could hear that arm on MF’s rig too! (Anyone who feels like donating a roundtrip airfare from LA to Casa Fremer, please be my guest).

Like that release, this one is again produced and engineered by the legendary Shawn Murphy, the bulk of whose career has been spent bringing us stunningly well recorded film soundtracks by the likes of John Williams, John Barry, James Horner et al. He has been the sonic point man on this entire Nelsons Shostakovich cycle.

I really should have headed this review with a little homage to the fourth installment in the Pink Panther series of films by titling it: “Shawn Murphy Strikes Again” - because, yes indeed, this recording is every bit the equal of its predecessor. However, because of the nature of the music and the solo instrument involved, it will not immediately hit you between the ears like a rocket going off, as does the Wang album. This one is more of a stealth attack which slowly gathers momentum - until you are likewise pinned to your listening chair, unable to resist.

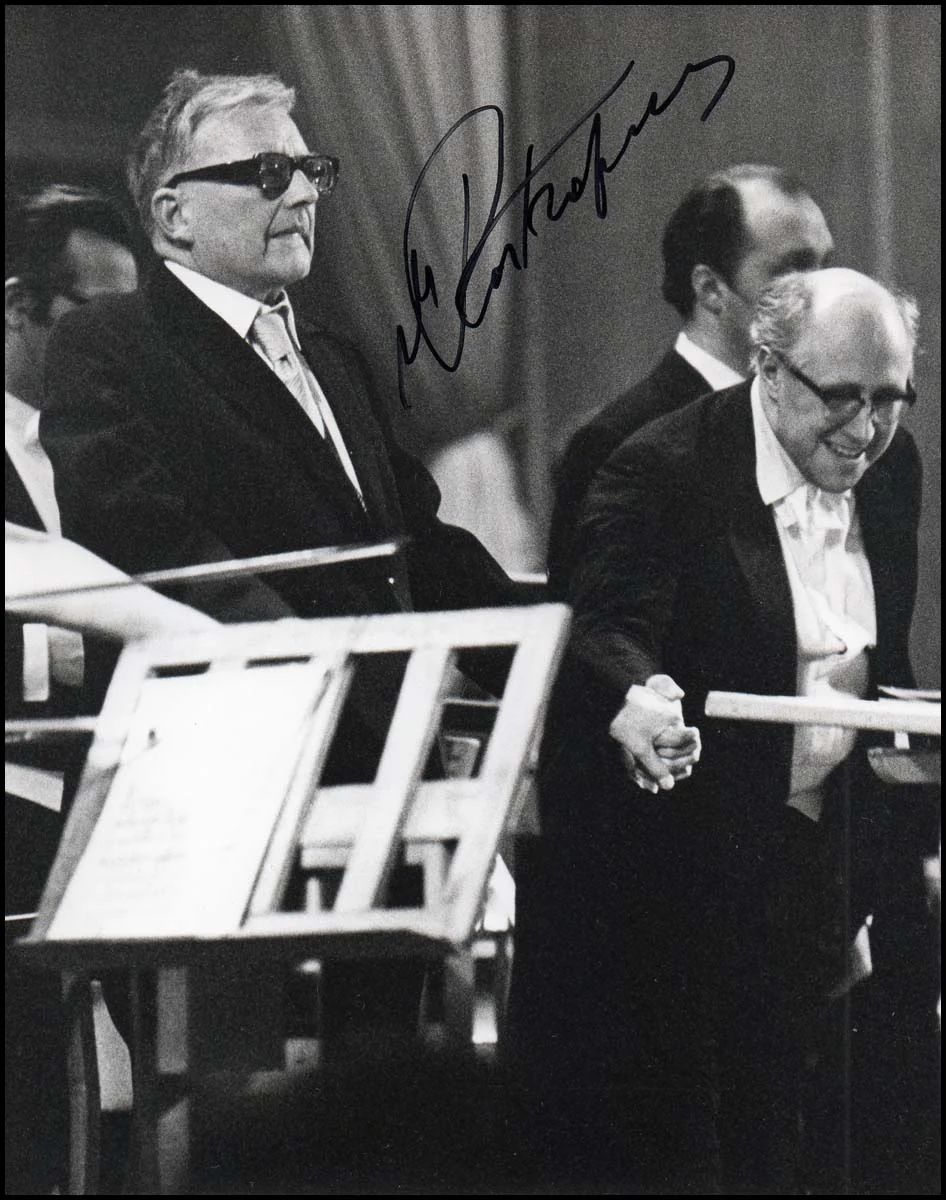

Shostakovich with Mstislav Rostropovich

Shostakovich with Mstislav Rostropovich

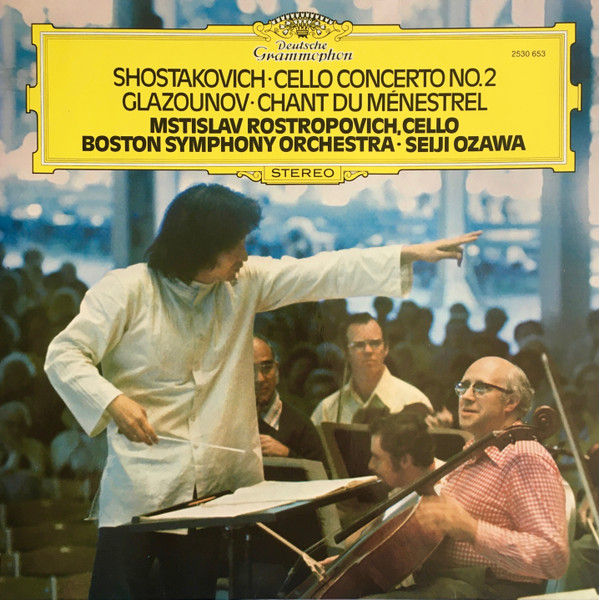

Shostakovich’s two concertos are core works in the ‘cello repertoire, both written for the great Russian virtuoso, Mstislav Rostropovich, who was the first to commit the works to disc. The first concerto was recorded in 1960 for Columbia Records in the US, where he was partnered by the Rolls Royce of American orchestras, the Philadelphia Orchestra, and its longtime Principal Conductor, Eugene Ormandy.

The second concerto was recorded in 1976, this time on DG with the same orchestra as featured in this new recording, the Boston Symphony, led by its then Principal Conductor, Seiji Ozawa (one of the finer sounding DG LPs of the time that I bought when it was released).

Both concertos exhibit the key characteristics we associate with Shostakovich’s distinctive musical temperament: a sense of sardonic wit and dark humour tempering an underlying profound romantic yearning that often turns to bleak despair. It’s a combination that perfectly encapsulates the unique circumstances of the composer’s life, where the stress of trying to survive a totalitarian, murderous regime which frequently had him in its sights, while also striving to preserve his artistic integrity, took a heavy emotional and physical toll. But it is this very modality, so expressive of the 20th century’s upheavals and contradictions, this combination of sincerity and mockery which causes his music to speak so strongly to us now in our own fragmented times. Shostakovich’s music has never been more popular.

While both concertos are indeed rooted in a similar, quintessentially “Shostakovich style”, they are actually quite different in how they come across to the listener: the first being more obviously extrovert, the second more introverted. Interestingly, it is the more outwardly reserved second concerto which boasts the larger orchestra, including a grand panoply of percussion that the composer puts to great use (and which Mr. Murphy and his team capture thrillingly). The first concerto uses essentially a chamber orchestra, supplemented (like the First Piano Concerto) by a lone brass instrument, in this case a French horn.

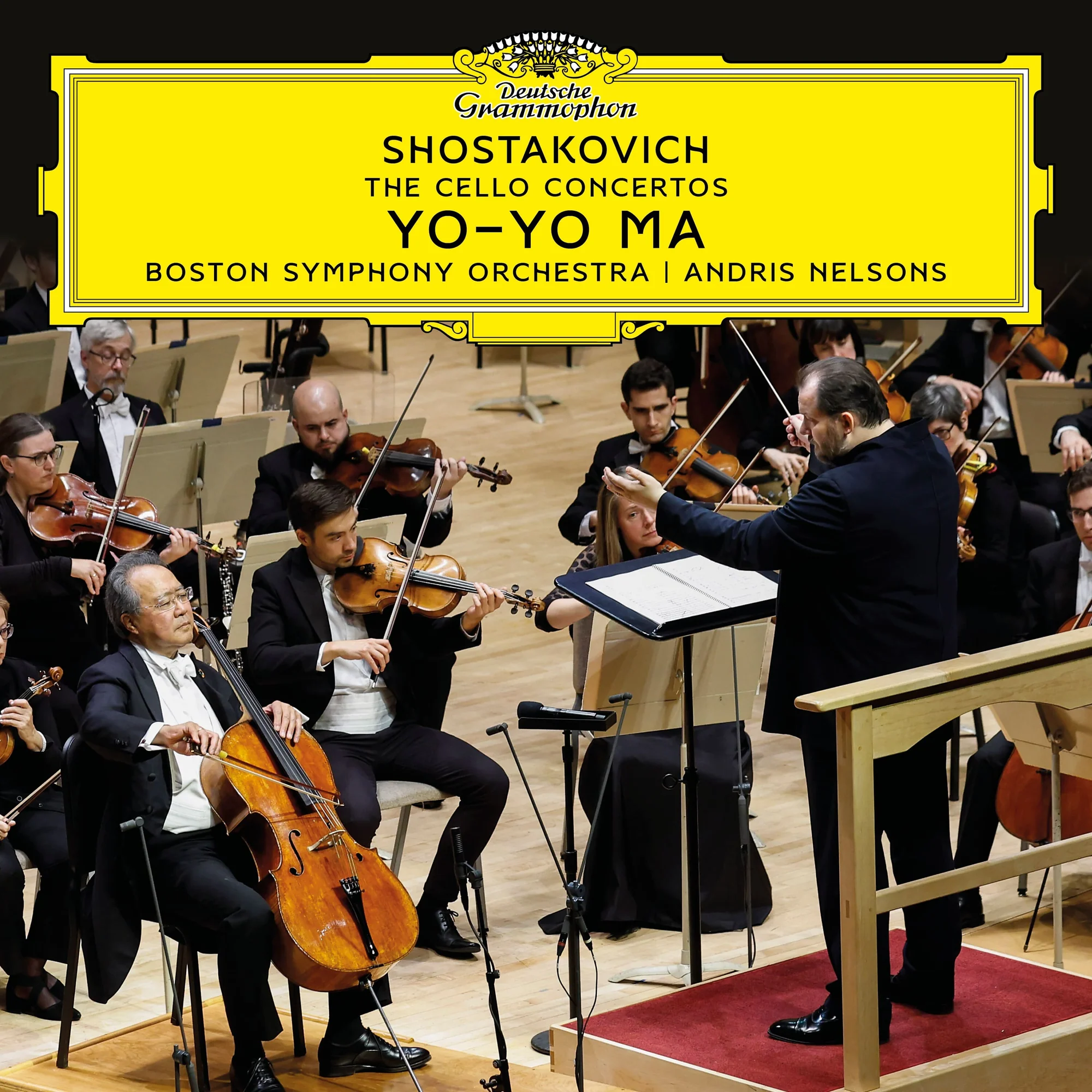

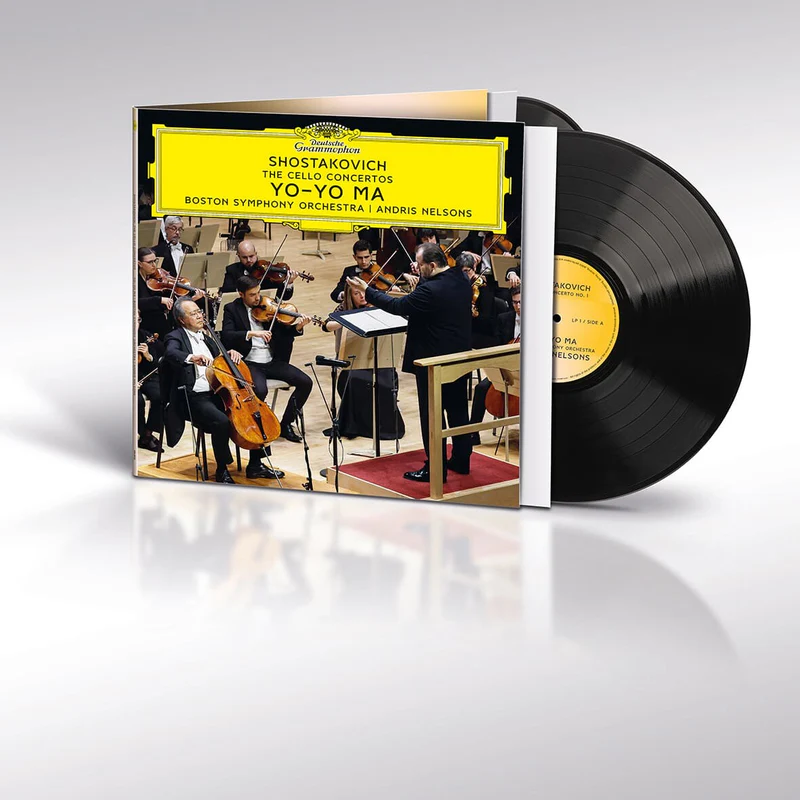

Yo-Yo Ma, Andris Nelsons and the Boston Symphony playing the Shostakovich 'cello concerti live in concert at Symphony Hall

Yo-Yo Ma, Andris Nelsons and the Boston Symphony playing the Shostakovich 'cello concerti live in concert at Symphony Hall

Opening with one of Shostakovich’s demented marches, you will quickly become aware of the composer’s distinctive use of low and high woodwind to punctuate the texture, and because of the seemingly endless headroom and deep bass of this recording these sonic detonations of low rasping bassoons and especially the shrieking piccolos have none of the aural constriction and discomfort one usually hears on other recordings, even good ones. The sound expands into the wide and deep soundstage effortlessly, and that word “effortlessly” is the one I would use to describe how this recording captures all the glistening detail of the remarkable orchestration of these works, from the most subtle, spookiest of effects to the most grandstanding tutti.

At the center of it all, of course, is the ‘cello, and here I must commend the team for not choosing to “spotlight” Ma’s gorgeously fulsome sounding instrument more than is absolutely necessary. (The liner notes do not state the instrument Ma is playing, but I will assume it is his habitual 1712 Davidov Stradivarius). The ‘cello here occupies a very realistic space in the middle of the stage, and when things get busy is occasionally subsumed into the overall orchestral picture - which is exactly as it should be. Otherwise there is clear separation between instruments and orchestral sections which helps to highlight the elaborate, almost chamber-like interplay between soloist and different parts of the orchestra.

Turning to other favorite recordings of these works, including Rostropovich’s own, I was struck that no other version was content to just let the instrument “be” in this manner; they all, to one degree or another, feel the need to slightly push the ‘cello into the spotlight. I found myself really enjoying the more natural presentation of the instrument on this new record. But this somewhat more recessed placement of the soloist in no way detracts from the instrument’s presence or one’s ability to hear every detail of Ma’s formidable playing.

Yo-Yo Ma during his "stadium" tour playing the unaccompanied Bach 'cello suites

Yo-Yo Ma during his "stadium" tour playing the unaccompanied Bach 'cello suites

What an instrument this ‘cello is, and man does Ma attack this thing. Firstly, the lower registers seem to almost resonate with the small platform on which Ma sits, and the stage beneath it. There is a profoundly “woody” quality to the sound. The bass is so deep, rich and colorful it almost beggars belief that one man and one ‘cello are creating this ravishing sound as it expands to resonate with the hall itself. There is little of the metallic ring you get from so many ‘cellists in the mid and high registers. This is amongst the most varied and richly textured ‘cello sound I have heard on record.

In the more complex passages Ma lays into this thing with a vehemence which belies his years. One well-known YouTube classical commentator referred to these performances as being “geriatric” - a judgment I am mystified by. (His negative comments on the engineering are likewise wide of the mark).

What you will hear, though, is an approach that is perhaps less obviously direct and on-the-nose than many. Ma is not afraid to linger in places, to pull back, to tease out more of the inner life of the music. This results in more moments of relative stasis, but because the recording itself creates such an inviting aural space, one leans in to these moments, and the tension is maintained. With a less colorful recording, this would be more of a problem.

Going back to that first movement of the First Concerto, yes Ma & co. are less obviously driven and laser focused than others (eg. Heinrich Schiff in his excellent rendition on Philips, an early digital recording that isn’t too shabby, but which suffers in comparison to the richer and more open sound provided by Murphy). In some ways Ma is "messier", but we also hear more of the (many) notes in the ‘cello part, and the sense of struggle, of sometimes fighting the orchestra and not exactly "winning" is a valid alternative to a more machine-like perfection.

Where this performance launches into the stratosphere is in the slow movement, an utterly spellbinding lament. In its latter stages Shostakovich creates an otherworldly passage for ‘cello playing harmonics accompanied by celesta, set against disembodied, interweaving unison strings at extreme low and high registers. A solo clarinet almost imperceptibly joins. Again, the expansiveness and precision of the recording allows all the spooky overtones of 'cello and celesta to emerge and fill the hall, and I found myself thinking of the scene with the witches in Macbeth, where the bloody usurper is confronted by ghostly apparitions. Is it entirely fanciful of me to imagine this is Shostakovich witnessing his own spectral procession of friends who had disappeared into the night, and ended their days in Stalin’s gulag?

Out of the mists the solo ‘cello emerges in what becomes a bravura solo cadenza, one full of virtuosic demands, but always at the service of a clear musical argument. You will hear the full sonic potential of the instrument, as pizzicati join other effects to create a compelling sense of an almost human voice bearing witness, wordlessly. Ma’s performance fills the hall. This is so brilliantly written and executed that it makes one wish Shostakovich had emulated Bach by creating his own solo 'cello suites for a modern age (as did Benjamin Britten), just as he had penned his own sets of piano Preludes and Fugues in the manner of the old master.

If the jaunty finale (again with piercing, shrill high wind and horn interjections) sounds to you like a demented peasant dance, that’s because it incorporates a distorted fragment from a Georgian folk song that was one of Stalin’s favorites.

Ma and Nelsons really bring out the almost demonic aspect of this high spirited Finale, complete with thundering timpani and screeching, Psycho-esque violins.

Shostakovich at his home in the countryside near Leningrad

Shostakovich at his home in the countryside near Leningrad

The Second Concerto, penned seven years later in 1966, opens with a winding phrase in the lower reaches of the ‘cello, immediately reminiscent of the opening of the 10th Symphony (1953) (similar echoes of that work appear throughout the movement). A melancholic mood dominates the whole concerto, but occasionally gives way to more playful passages. Here we move into an extraordinary sequence for harp, xylophone and wind that sounds like a children’s playground chant, although (naturally, this being Shostakovich) tinged with a sardonic edge. Again, the engineers capture all the multi-hued colors and timbres of these unusual combinations of instruments in a manner no other recording matches.

Then, in a surprising coup de théâtre, the jauntiness collapses into a duet between ‘cello and, of all things, bass drum. You will hear every detail of the stick hitting the drum’s skin, and the sound filling the hall as the soloist struggles to hold his own.

Finally the opening melancholic melody returns, haltingly. Here, as elsewhere, there is an emphasis on bass toned instruments like ‘celli, double bass, bassoon, offset by harp - the shadows grow long, and a lone French horn calls out in a manner reminiscent of Britten’s use of the instrument in his Serenade for Tenor, Horn and Strings (a work which Shostakovich would’ve known well; the two men were mutual admirers).

(from left to right) Rostropovich, violinist David Oistrakh, Benjamin Britten and Shostakovich

(from left to right) Rostropovich, violinist David Oistrakh, Benjamin Britten and Shostakovich

The jaunty short scherzo which follows has the quality of chamber music, as does much of the concerto, with the composer using his large orchestra more for accessing a wide variety of sonic textures than providing a "wall of sound". The thematic material would have given the first audience something to smile about, since it is a distorted treatment of an Odessa street vendor’s song, which roughly translates as “Buy Our Pretzels”.

This movement is full of the most wonderful juxtapositions of instruments that are rarely pitted against each other. I found myself thinking often of the great film composer Bernard Herrmann’s unusual use of the orchestra and similarly incongruent but highly effective combinations of instruments. Again, Murphy and his team’s engineering makes all of this sound more vivid and three-dimensional than I have heard elsewhere.

A somewhat unhinged sequence of brass fanfares announces the uninterrupted transition into the Finale. Let me just mention here a most striking effect that recurs throughout the movement, where Shostakovich reaches a resolving cadence, and the ‘cello gives us a Baroque-style trill and termination. Most neoclassical, unexpected, and quite wonderful - it acts as a kind of recurring signpost along the way.

The rest of the movement unfolds in a series of juxtapositions, with an almost forced sense of gaiety. On the surface there is levity, but something darker lurks beneath.

This culminates in a brash, unison statement of the Odessa pretzel song, one of the few loud tutti throughout the work - jaunty yet also desperate, an impression enhanced by interjected loud, sharp whip cracks. “Dance and Sing - or else…!” the music seems to say.

Frenetic solo ‘cello work moves us into a wind-down in which the melancholy air returns, and that Baroque trill repeats. There is a sense of the music falling slowly, inevitably into dark introspection.

As in his future 15th Symphony, all finally devolves to the percussion, with wood block, tom-tom, snare drum, and xylophone beating out a quiet, eerie chatter against a low sustained ‘cello note.

And then the work simply… stops.

“This is the way the world ends

Not with a bang but a whimper…”

Shostakovich in 1961 (Photo by Vsevolod Tarasevich)

Shostakovich in 1961 (Photo by Vsevolod Tarasevich)

The Second Concerto is, in many ways, a much harder work to wrap one’s head around than the First, and it can seem diffuse and unfocused at times. We are far away from the world of virtuosic showpieces designed to show off the soloist’s chops, even though there is some formidably challenging stuff for the 'cellist to wrap his fingers and bow around. Yo-Yo Ma’s conception is again less laser-focused than many others, less obviously driven, but it is an approach that leaves more room for the music to breathe, and for the listener to enter into a dialogue with the performance. This is further enhanced by the entirely natural, open sound which, like the sound provided by Murphy and his team for Yuja Wang’s record, sets new standards for classical digital recording, and for DG. (Maybe we can get some of Nelsons’ Shostakovich symphonies on vinyl now).

Andris Nelsons with the Boston Symphony Orchestra

Andris Nelsons with the Boston Symphony Orchestra

Throughout, the Boston Symphony brings an almost vintage Soviet quality to their playing - in all the best ways. Wind and brass rasp, strings bite and soothe (but with an edge), percussion slices and dices. It's a thrilling, authentically Russian sound (albeit more polished), a perfect match for Shostakovich's musical canvas. Nelsons is really engaged with the music in a manner than can elude him in, say, Bruckner and Beethoven.

My otherwise perfect pressing (from Optimal) had a run of clicks for about twelve revolutions in the slow movement of the First Concerto, but it is nothing I cannot live with. As with the Yuja Wang record (and noted by MF), the actual lacquer cutting is first rate, and was apparently done by an anonymous engineer at Optimal itself - kudos to whoever it was. Good sleeve notes with some nice historical detail and quotes are provided by Harlow Robinson.

Shostakovich and Rostropovich in the Blue Room of the Great Hall of the Leningrad Philharmonic after the premiere of the First 'Cello Concerto on 4th October, 1959.

Shostakovich and Rostropovich in the Blue Room of the Great Hall of the Leningrad Philharmonic after the premiere of the First 'Cello Concerto on 4th October, 1959.

Collectors will absolutely have to own the two Rostropovich renditions of these works. The First Concerto can be hunted down in a very fine Speaker’s Corner audiophile reissue (pictured earlier in this review), which I believe was cut by Kevin Gray as a part of a run of Columbia remasters he did for the label, which are all improvements on original pressings. The Second Concerto is a prime candidate for Original Source reissue, but now with this stellar rendering in its catalogue, who knows if DG will take the plunge. If you must have it now, seek out (again) the Speaker's Corner reissue.

Yo-Yo Ma’s excellent first recording of the First Concerto (one of his earliest studio forays) with Eugene Ormandy and the Philadelphians is best heard in its new remastering in the most recent Ormandy Complete Philadelphia Stereo Recordings Box (the third of the three Sony Ormandy boxes - one mono, two stereo - to be released). My hitherto favored vinyl coupling of both concertos on one record together was on Philips by Heinrich Schiff with the composer’s son Maxim at the helm, but it is now sonically thoroughly superseded, though it remains one of the best performances, more streamlined and relentless than Ma. On CD, two favored renditions are by Mischa Maisky and Michael Tilson Thomas plus the LSO (DG), and Alban Gerhardt with Jukka-Pekka Saraste and the WDR Symphony Orchestra (Hyperion). But no-one comes close to the sonics of this new version.

With apologies to everyone’s bank accounts, I hate to repeat myself but, yes, this is another essential purchase for classical vinyl fans. And please, DG, persuade Shawn Murphy to produce and engineer more of your new recordings. He is a Master of the Sonic Arts.

Available for purchase at the DG site and at Acoustic Sounds

There are many terrific videos of Yo-Yo Ma playing and talking about his wide range of music making on the web, but this is a great introduction to what he does and how he does it.

.png)