Ozawa's Ravel Box: A High Point For Both Conductor and Orchestra

The new 4LP box set from DG's Original Source series contains one of the best Ravel cycles you can buy

This year marks the 150th anniversary of the birth of one of France’s most distinctive artistic voices: Maurice Ravel (1875-1937). When one thinks of French painting, they think of Claude Monet. When one thinks of French sculptor’s, they’ll likely conjure to mind Auguste Rodin; and when one thinks of French music, the melodies that enter their head are likely to sound a lot like those of either Claude Debussy or Maurice Ravel. Both composers contributed greatly to what the average listener identifies as “French” sounding music from the 19th and 20th centuries.

Both Debussy and Ravel were outsiders, and rather ironically, shunned by much of the French musical establishment in their day, despite shaping it substantially. Debussy broke every rule in the playbook when he emerged as a force in late 19th century Paris, employing a far less rigid harmonic language and structure, while changing the associative function of music in the imagination of the public. Debussy became associated with the term “Impressionism” which he both accepted and shunned at various points in his career. This was an allusion to impressionist painters such as Claude Monet (1840-1926) and Camille Pissarro (1830-1903) that emerged in the previous decades. Debussy’s music was not just harmonically adventurous, building upon the tonal foundation of German composers like Richard Wagner, but he also pursued entirely different themes in his work. Much of Debussy’s artistic ideas were about representing mood and feeling through music, rather than telling a story or portraying particular events. Thus, the comparison with visual “Impressionism” stuck.

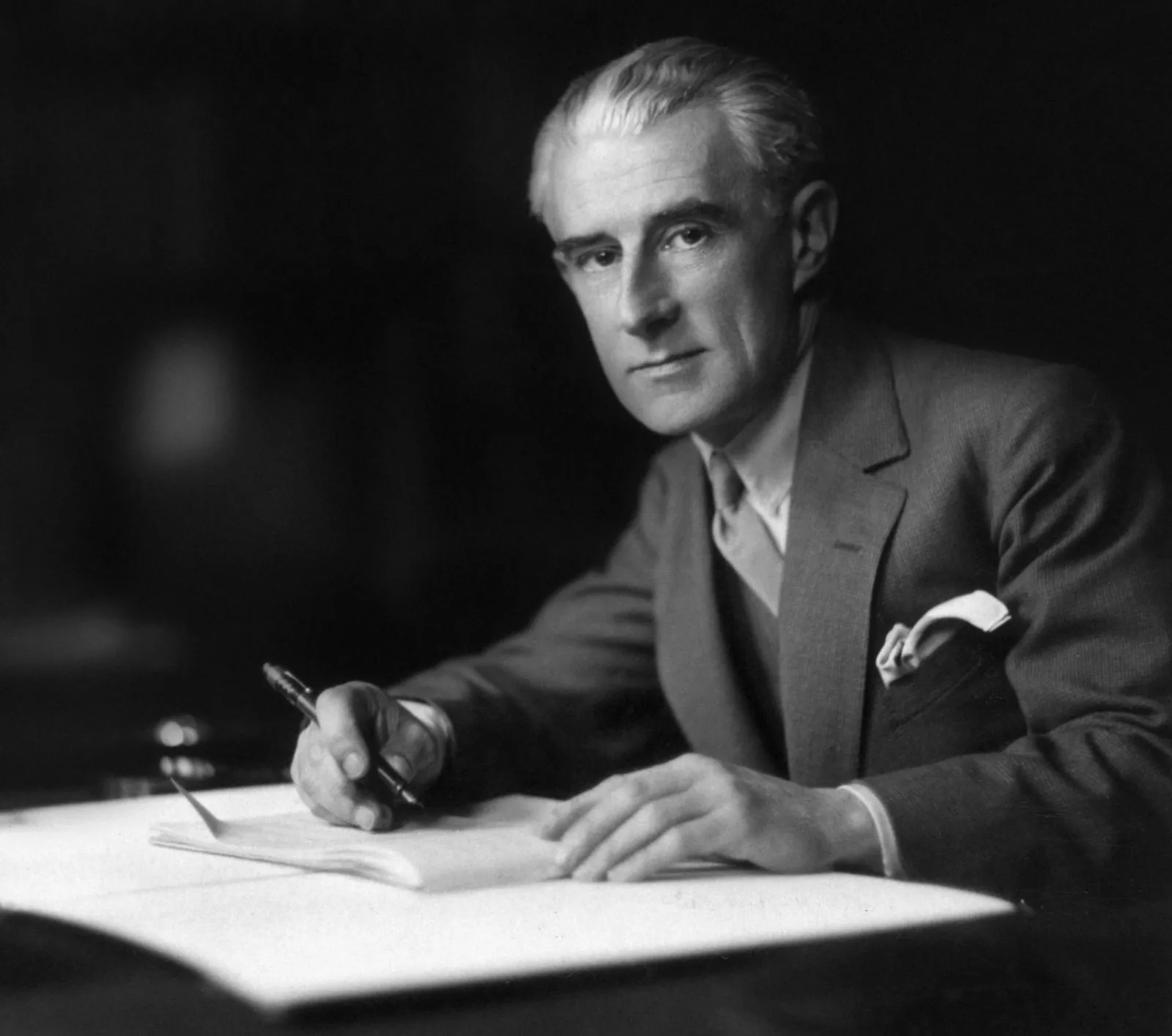

Maurice Ravel

Maurice Ravel

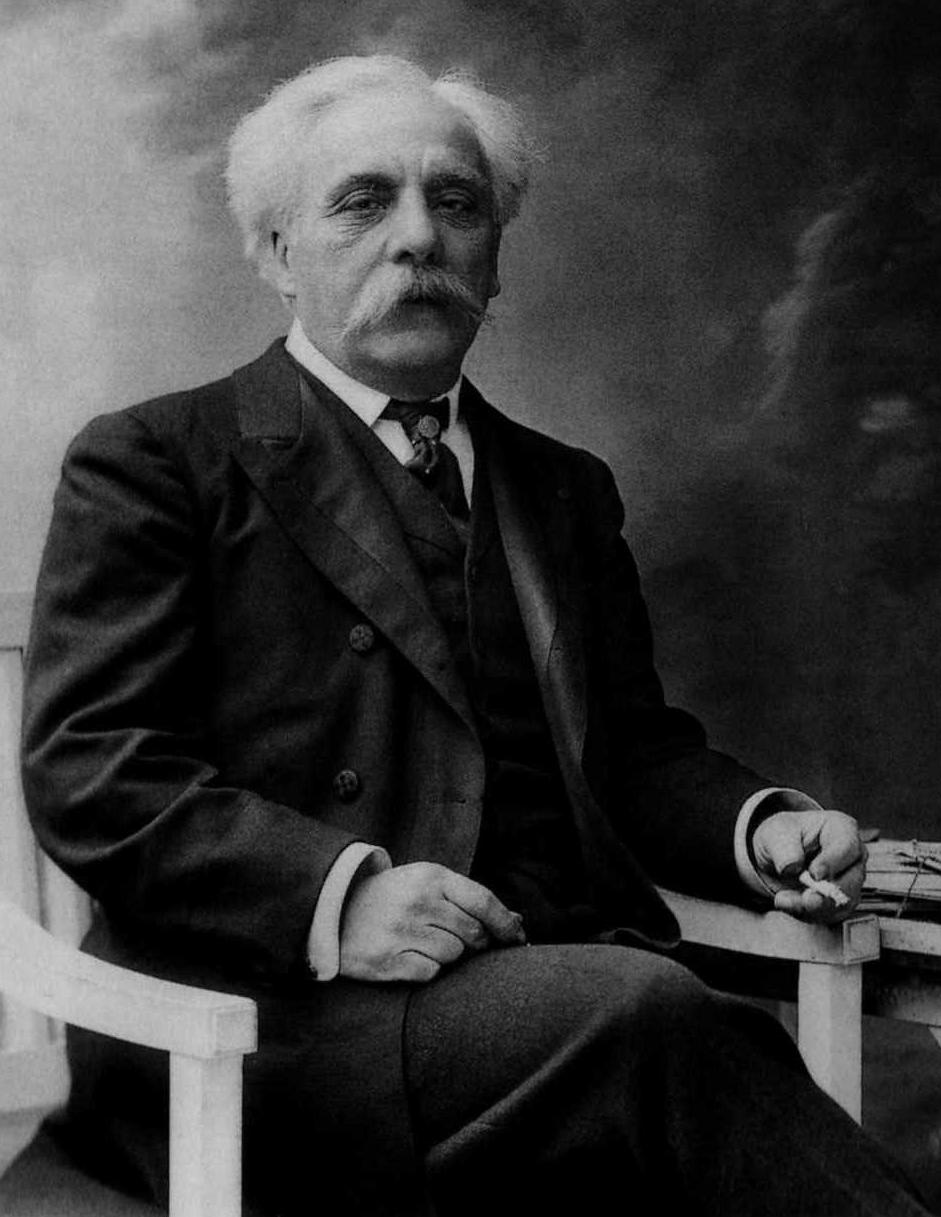

Maurice Ravel was 12 years Debussy’s junior and never formally studied with him, but he was a deep admirer. Born to a modest middle-class family he entered the Paris Conservatory in 1889 as a pianist, but developed a keen interest in composition as well. He was expelled in 1895 because as is the tradition of the French Conservatory system, students must win a major award to graduate. Prior to his expulsion he spent a period of time composing some of his earliest works such as Menuet Antique (the orchestration of this work being one of the performances in this box set) and the Habanera. He was readmitted to the school in 1897 and began studying with Gabriel Fauré who encouraged and supported him despite Ravel’s work sounding little like the older 19th century style of Faure’s. Debussy was fascinated with the more avant-garde composers of his day, which of course included Debussy who was already making waves at this point, but also the music of Erik Satie who was far ahead of his time in many ways in regards to composing in a hyper minimal style.

Gabriel Fauré, one of Ravel's primary composition teachers and advocates

Gabriel Fauré, one of Ravel's primary composition teachers and advocates

Ravel’s forward-thinking compositional outlook earned him many detractors in the established musical world, including the president of the conservatory Théodore Dubois. He eventually was expelled again in 1900, and was snubbed from many awards thereafter, perhaps most famously the Prix de Rome, in which Dubois personally intervened to prevent his success. Despite all these setbacks, eventually Ravel found success in his chosen profession, and between roughly 1905 and his death in 1937 he produced a meticulous but steady output of piano, orchestral, and vocal works that received greater and greater acclaim. He only produced roughly 80 works, which may sound minuscule compared to many composers, but despite that figure, Ravel has firmly established himself in the canon of classical music and is one of the most frequently performed composers of the 20th century.

Ravel’s music certainly was more modern than that of his contemporaries, particularly in France, but that does not mean he was outside of convention or established compositional building blocks. His music is very intricate and has form and structure that harkens to early romantic and classical composition. In fact, that’s one of the things that distinctly sets him apart from the other major French “impressionist” Claude Debussy, even though both composers were masters at creating color and mood, and both employed similar harmonic techniques such as the frequent use of parallel 5ths and octaves (a taboo in counterpoint since the Renaissance.) But when you unravel the score of a Ravel work, whether it be keyboard or orchestral, you do get the sense that you are looking at the mechanism of a bespoke Swiss watch.

It's worth mentioning that Ravel is often considered by many to be one of the greatest orchestrators that ever lived. Many of his works began life as piano pieces and eventually found new life as grand orchestral suites. He also orchestrated many works by other composers with great success. The most well-known of these orchestrations has to be of Modest Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition which was originally written for piano. Yet today, it is not Mussorgsky’s piano version we know best, but Ravel’s rich orchestral suite. Other examples include (a sadly lost) Frédéric Chopin’s Les Sylphides, and Robert Schumann’s Carnaval.

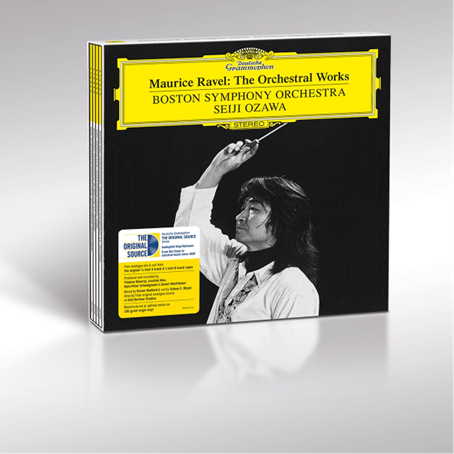

Unfortunately, none of those orchestrations appear in this box set by Seiji Ozawa and the Boston Symphony Orchestra, but what is contained on these 4 LPs is the vast majority of the composer’s original orchestral work minus a few vocal-based compositions such as his early Shéhérazade song cycle and his operetta L'enfant et les sortilèges. Below is the track listing for each LP:

LP 1 – Side A:

1. Boléro, M. 81 (1927)

2. Rapsodie espagnole, M.54 (1907)

LP 1 – Side B:

1. Rapsodie espagnole, M.54 (continued)

2. La valse, M.72 (1920)

LP 2 – Side A:

1. Ma mère l'oye/Mother Goose M.60 (1911)

LP 2 – Side B:

1. Menuet antique - M. 7 (1929)

2. Le Tombeau de Couperin, M.68 (1919)

LP 3 – Side A:

1. Daphnis et Chloé, M. 57 / Première partie (1912)

LP 3 – Side B:

1. Daphnis et Chloé, M. 57 / Deuxième partie

2. Daphnis et Chloé, M. 57 / Troisième partie

LP 4 – Side A:

1. Valses nobles et sentimentales, M.61 (1912)

2. Une barque sur l'océan M.43 (1919)

LP 4 – Side B:

1. Pavane pour une infante défunte, M. 19 (1910)

2. Alborada del gracioso, M. 43 (1919)

This collection of Ravel recordings was a statement piece by the BSO’s brand new music director Seiji Ozawa. Ozawa’s history with the BSO is rich. The Japanese conductor, born during the Asia-Pacific war (in occupied Manchuria no less), had gotten his big break from the orchestra’s longtime music director Charles Munch, who invited him to Tanglewood (the orchestra’s summer home) as a young man to study with himself and Pierre Monteux. There at Tanglewood he won the Koussevitzky prize for student conducting which earned him a scholarship to study with Berlin Philharmonic music director Herbert von Karajan. He also managed to attract the attention of Leonard Bernstein who appointed him his assistant conductor at the New York Philharmonic.

Ozawa held brief music director posts at both the Toronto and San Francisco Symphonies, but in 1973 at just 38 years old, he was appointed director of the Boston Symphony, an orchestra he would lead for 29 years, the longest tenure of any music director in the organization’s history. The BSO had great difficulty settling on a music director in the days since the tenure of Charles Munch (many of whose recordings on RCA with the BSO are currently in print via Analogue Productions). Leinsdorf, who succeeded Munch, had notable clashes with the orchestra musicians, and William Steinberg, who followed after, was elderly and in poor health. After a long search the board eventually chose the young Seiji Ozawa, who at the time seemed to be on the verge of conquering the conducting world.

Ozawa’s long tenure with Boston was not without a good bit of controversy. The orchestra had long been noted for its distinctly French sound, due in part to the large numbers of French immigrants who joined the orchestra during the 1910s and 20s. Ozawa’s concept of orchestral sound, as well as his training with Karajan, was centered on the German school. Over time, the orchestra’s sound did change, towards a sound that was heavier, particularly with greater use of the bow in the string section. This eventual change perhaps prompted the resignation of long time BSO concertmaster Joseph Silverstein who was regarded as one of the best concertmasters in the world at the time.

Over the years, more cracks in Ozawa’s directorship would fracture the American musical scene, including a spat of high-profile resignations at Tanglewood accusing Ozawa of dictatorial control over the festival. Critics were also somewhat divided on his legacy upon retirement, with some praising his bold, energetic performances, while others decried what they perceived to be declining standards of artistry in the orchestra. No doubt, Ozawa definitely had a target on his back being the first Asian maestro of any major American orchestra, and how much that influenced his detractors is certainly up for debate.

A local ABC Boston report on Ozawa's final year with the BSO in 2002

I will not weigh-in as to the verdict on Ozawa’s record through his 29-year tenure, but I will give my thoughts on these recordings done during the honeymoon of the young conductor with his new orchestra.

All of the four LPs in this box set were recorded between 1974 and 1975 in Boston Symphony Hall, a venue with one of the most renowned and distinctive acoustics in North America. You see, Symphony Hall, built in 1900, was one of the first concert halls designed with mathematical acoustic principals in mind. It was in part modeled on the famous Leipzig Gewandhaus which was sadly destroyed in the second world war. The hall, designed by physicist Wallace Clement Sabine, was specifically designed to yield a reverberation time of between 1.9-2.1 seconds which is considered to be an ideal balance between liveliness and transparency. The BSO players clearly had an ideal setting to bring to life the colors of Ravel’s orchestration, but given the rich history of great recordings set in this space, they still had hurdles to surmount.

Boston Symphony Hall

Boston Symphony Hall

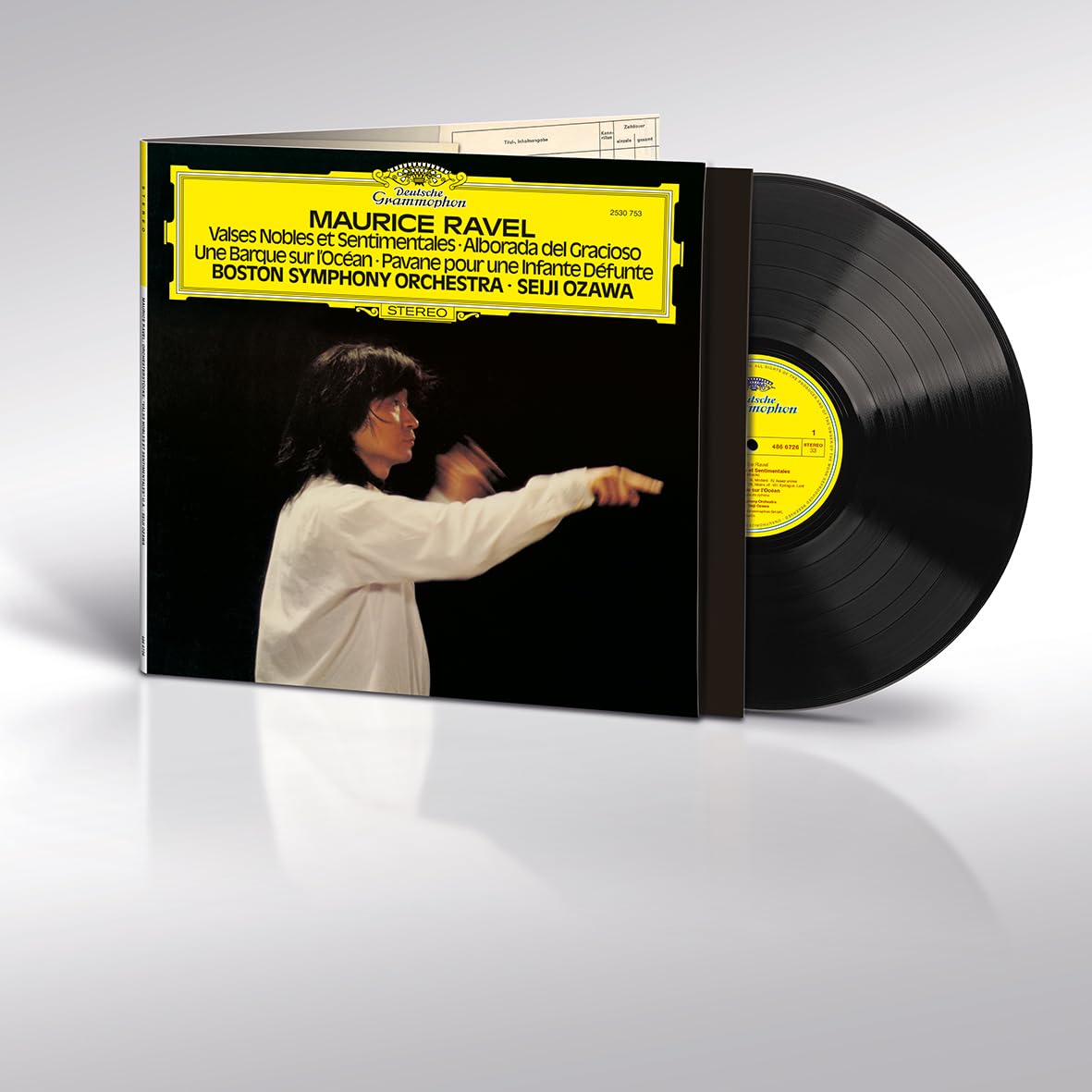

Let’s start with the music first, which encompasses everything from grand orchestral epics to petit miniature works. The first record I chose to listen to in the set was that of the four shorter works: Valses Nobles et Sentimentales, Alborada del Gracioso, Une Barque sur l’Océan, and Pavane pour une Infante Défunte. Putting on side two was where I got two of my most familiar works; the Pavane and Alborada del Gracioso, two contrasting works that are often paired together on programs. In fact, one of my best sounding classical LPs is my Classic Records single-sided 45rpm pressing of Mercury SR 90313 with Paul Paray and Detroit playing this exact combination of works. On that record the Spanish-styled Alborada is red hot and taken at one of the fastest tempos I have ever heard for the piece. While the Pavane is slightly less convincing and not my favorite account.

The Ozawa reading by contrast, is more measured. First, the Pavane, has a more organized tempo even though he takes the line slightly slower. There is a sense that the orchestra is playing more “together” than the Paray, which is musically quite complex but not every handoff is as clean as what the BSO players can accomplish. BSO Principal horn Charles Kavaloski is a star in this work and phrases with sensitivity while allowing his tone to shine through the acoustic of the hall. This was the BSO at the top of their game, and the players in this orchestra at this time were uniquely suited to be able to tackle this delicate music. The Pavane is often mistakenly played with a sorrowful quality that doesn’t really suit the composer’s intention, as Ravel specifically wanted this work to represent a courtly dance of a princess from long ago, not be a funeral dirge for a tragically deceased princess (what the work often turns into). But you don’t have to take my word for it, you can hear the composer’s own performance of the work on piano roll, “recorded” in 1922 (for player piano).

The Alborada on the other hand, did lack some of the speed and ferocity of the Paray (most recordings of this piece do), but what makes up for that is the sheer impenetrability of the player’s technique which allows a for a much more transparent performance full of all of the composer’s clock-like wonder.

When I flipped over to the A side, I think I got why this cycle is so revered, and it’s because Ozawa and the BSO were able to render this music with a transparency that is unrivaled by any other recordings I can think of. Take the Valse Nobles et Sentimentales for example; a collection of character waltzes the composer wrote in tribute to Franz Schubert. All the colors of Ravel’s music come out here, from the subdued and gentle, to the explosive and manic. And those changes are so dramatic and apparent partially because Ozawa does not over-sentimentalize the work, his timing choices are incredibly balanced.

By the time I got to Une Barque sur l”Océan, I was sold. This is a lesser-known short work by the composer, but it’s a fantastic encapsulation of Ravel’s more impressionist tendencies. So much of this piece, which depicts the rising ocean waves lifting a lone sailing ship across the vast sea, is built on atmosphere, that ethereal quality in the beds of chords laid at the beginning of the work, and how that atmosphere can swell effortlessly, like the waves, into something dangerous and overwhelming in scope. I admit I haven’t heard nearly as many performances of this work as I have others in this set, but Ozawa left me with such awe in this account that I’m not in a hurry to track down others.

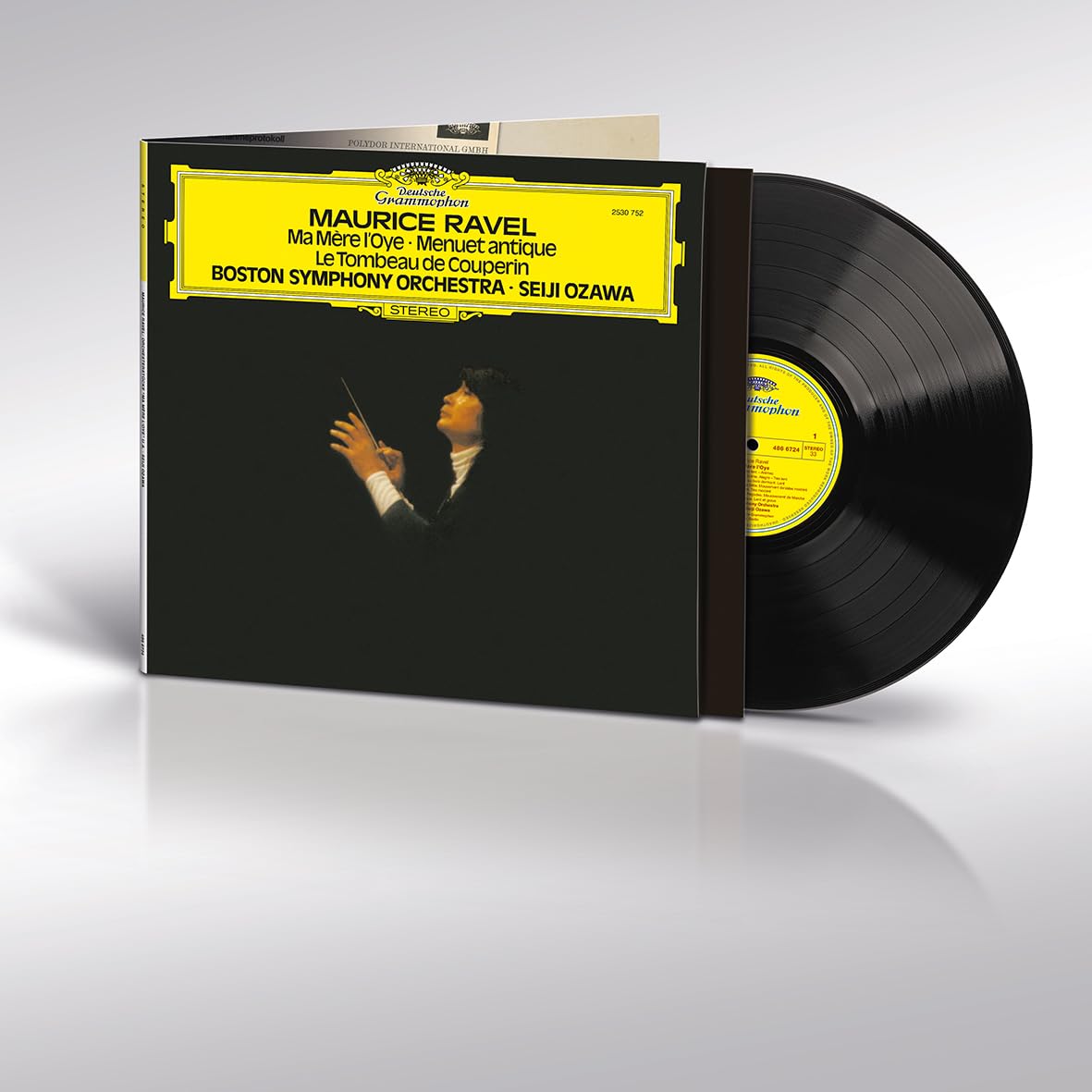

Another stand-out LP in this set features three of my favorite Ravel works, the full Mother Goose ballet, Le Tombeau de Couperin, and the short but blissful Menuet Antique (another early music throwback). The Menuet and Le Tombeau are excellent pairings as they both use traditional dance suite forms. Ozawa is adept at highlighting the traditional underpinnings of these 20th century works, and the counterpoint is phrased with poise and the appropriate forward energy, particularly in the Menuet. I was especially impressed with how tight the accompaniment (the staccato low brass chords were sharp and defined) was during dynamic sections of the work.

I am more familiar with Le Tombeau de Couperin (literally translated as “the Tomb of Couperin”) than most other works in the orchestral repertoire. The piece, written originally as a piano suite in tribute to Ravel’s friends who were killed in the line of duty in the first world war, was orchestrated by the composer in 1919 and features the oboe prominently throughout the work. This is likely a nod to the style of Francois Couperin (1668-1733) whose dance suites for the court of Louis XIV were performed predominantly on the oboe. Le Tombeau and its opening 16th notes have become one of the most standard excerpts in oboe-dom, and I’ve played the prelude on almost every professional audition I have ever taken.

The classic 50s and 60s recordings of this work are beautiful; the Paray, Cluytens, Ansermet, and even the Skrowaczewski all have their interpretive charms. However, if you hold the playing, particularly the woodwind playing, of those recordings up to the modern standard, few fare well. This recording from late 1974 marks a turning point in recorded versions of this work, where the playing is definitively clean and considered. Don’t let me make you think this means the performance here is dry or witless, it’s absolutely not. In fact, it is full of life, vitality and color, but now you can hear deeper into the score because of the refinement of the Boston players, particularly the dazzling oboe feats of Ralph Gomberg, younger brother of New York Philharmonic oboist Harold Gomberg (both of whom studied with Marcel Tabuteau at Curtis). Gomberg’s playing here truly stands up to most modern recordings of this work I’ve heard, and remains fresh and musical even to this day.

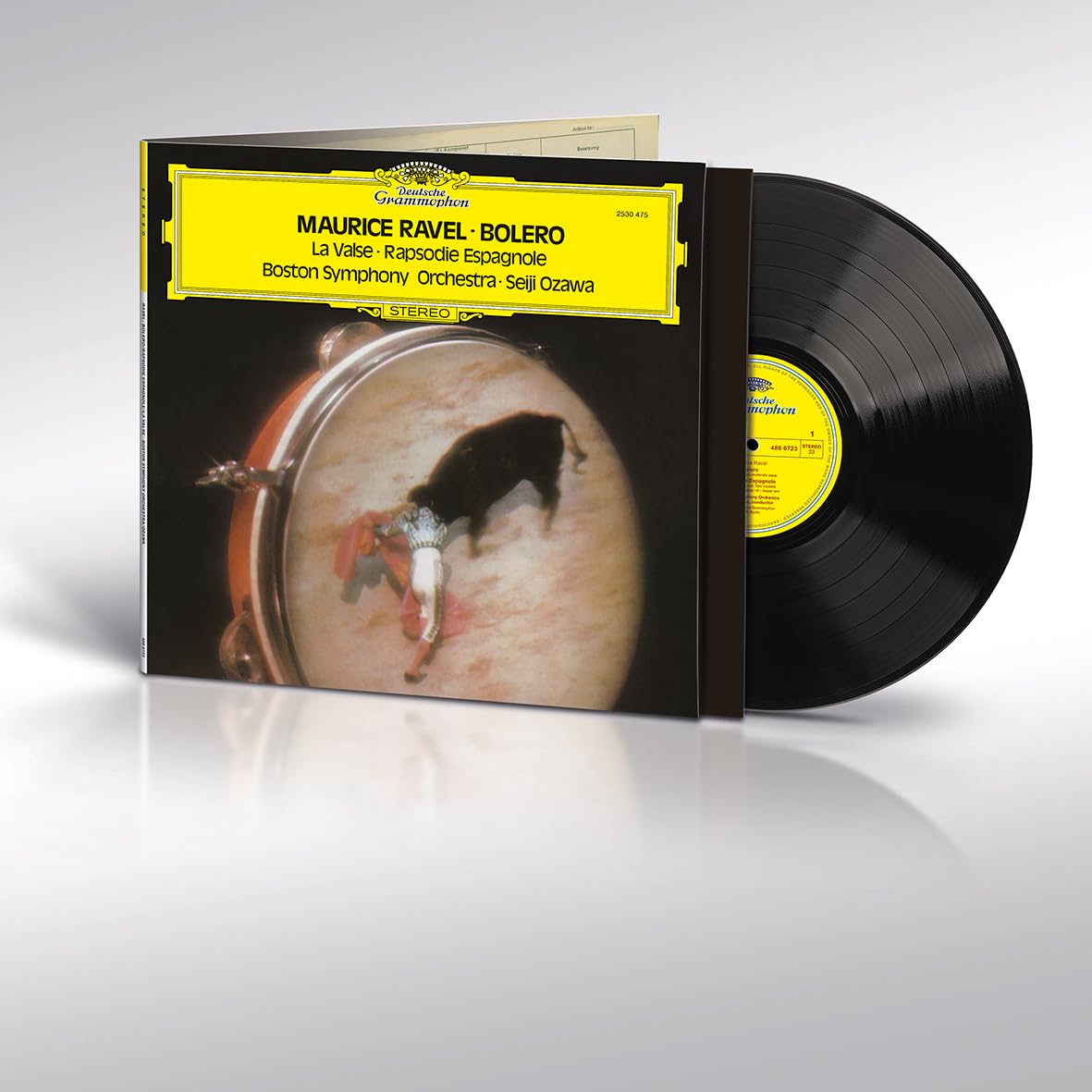

To turn to the big guns, we look at the remaining two LPs, one which features three of the composer’s most often performed war horses: Bolero, Rhapsodie Espagnole, and La Valse. None of the performances on any of these LPs are anything close to weak, however this three-work program is easily the crème de la crème. Bolero is such an interesting work in and of itself, one of the composer’s final orchestral compositions, it is a theme repeated endlessly without variation. Some renditions of Bolero treat it as a light and fun showpiece for the various instruments of the orchestra. But I think the Bolero presented here is a more convincing one, one that enjoys the madness of the incessant, never ending theme, and ramps up the drama a bit. It’s a bold, quick, and sardonic rendition that gave me a new appreciation for the piece.

Ravel’s fascination with Spain (he was of Basque heritage, but never visited the country until 1923) had its most fully conceived outlet in his Rhapsodie Espagnole from 1907, and here Ozawa ramps up the drama with controlled bursts of accent, texture, and aplomb. All the cadenzas are dramatic and musical, and the way at which the orchestra is able to dance between intimacy and force, is a tribute to the collaboration between musicians and conductor. La Valse, Ravel’s apocalyptic waltz for end of the world, also makes use of this line, but true to the score it teeters even closer to the brink of cohesion and good taste. I have played La Valse, and it is one of the composer’s most challenging scores. To be successful, the orchestra has to both execute daring turns of technique and tempo changes, and portray the feeling of being out-of-control, while actually staying together and in-control. Many recordings I have heard of this work end up sounding blurry not because of the sound quality, but because the flurry of notes are too frantic and quite frankly just not clean. This recording with the BSO is a clear-cut exhibit that cleanliness absolutely does not sacrifice soul or drama, as this is one of the most thrilling La Valse performances I’ve heard on record.

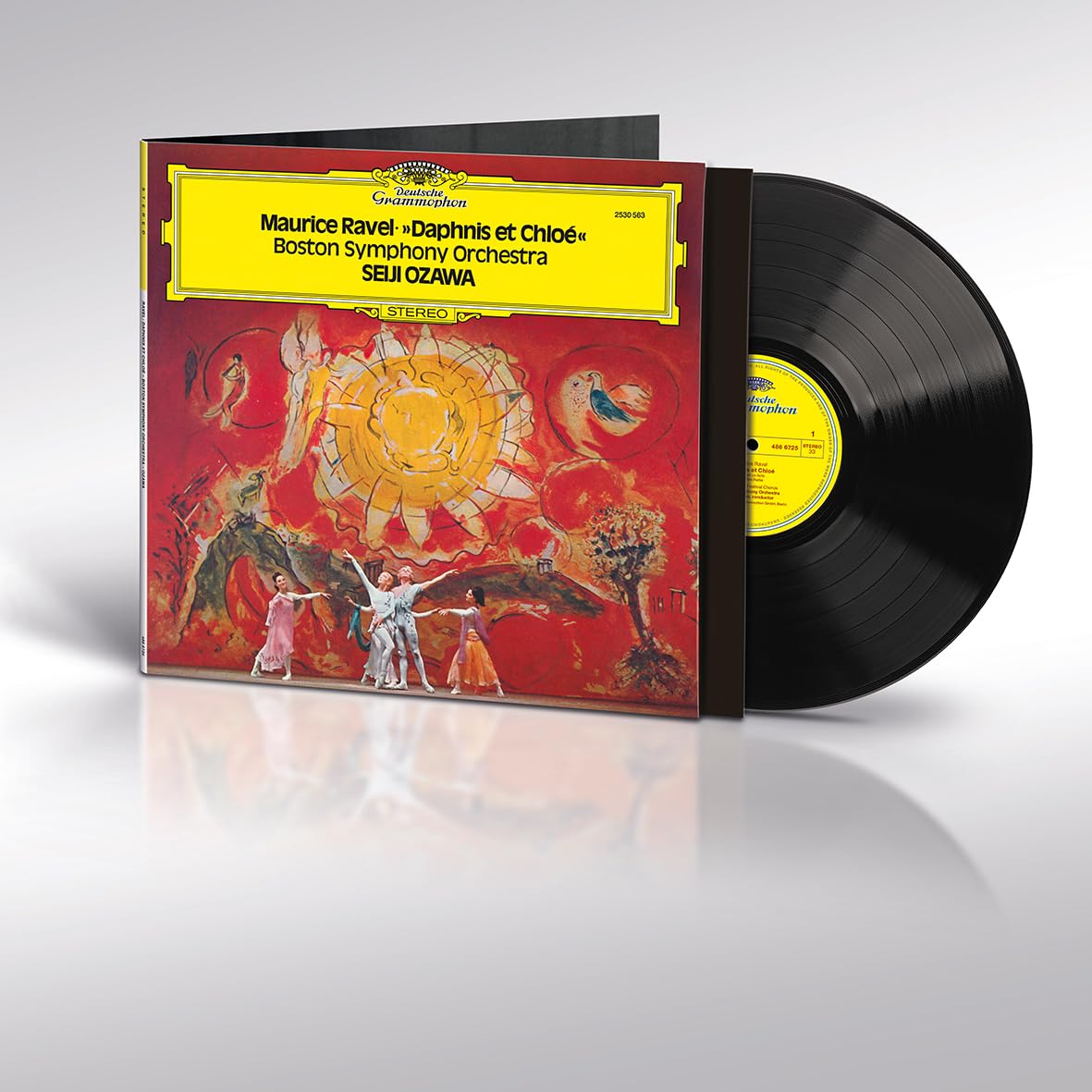

This leaves one final disc, a complete recording of Daphnis and Chloe, Ravel’s “choreographic symphony” performed with a full choir courtesy of the Tanglewood Festival Chorus. The Boston Symphony has a long and storied history with this work, and it’s one of their most frequently recorded pieces of repertoire. Charles Munch recorded the full ballet twice for RCA, and just four years earlier Claudio Abbado came and recorded the Suite No. 2 (basically the second half of the ballet) with DG to much success. This was clearly a trial piece for Ozawa to leave his mark on, and he certainly does. This Daphnis is refined, controlled, energetic, and simply brilliant. This work, like La Valse, is fiendishly difficult and technical. Here in 1974 the BSO is arguably at the top of their game and well-versed in this music. Many critics accused Ozawa over the years of not having an artistic vision when he approached repertoire, but those critics clearly weren’t referring to this performance which is thoughtful and emotive.

There are other great Daphnis recordings, don’t get me wrong. Munch did it spectacularly twice, Monteux has a brilliant account with London on Decca, Cluytens’ version is incredibly soulful and spiritual, and Dutoit and Montreal helped raise the already high bar set by all these other versions. But among this pantheon, the Ozawa is still one of the greats. The playing by the BSO winds here is simply virtuosic, it is not often I hear those difficult clarinet passages, especially at the end of the work, executed with such ability and authority. The orchestra also is keen to tackle the dynamic and mood shifts that this piece requires, and all I’ll say is that if you feel like being enveloped in a wave of sound, there are places in this performance that will give you that sensation.

In regards to the performances, Ozawa and the BSO have rendered one of the best Ravel cycles you can get from the analog era. The only competitors I can think of are the Cluytens which is very hard to find in complete form (although the individual records are cheap and easy to get on the Classics for Pleasure label), and the individually released Dutoit records on London Digital. Neither sound quite as good, especially in regards to bass and dynamics, as these new Original Source LPs. There are of course great individual records that are easy to recommend, but they are mostly going to be competitors, not outright winners. For a discussion on other great sounding Ravel recordings available on vinyl, please watch the video I recorded with fellow Tracking Angle contributor Mark Ward.

To comment further on the sound at the end of all this exposition: these recordings, unveiled by the Emil Berliner team of Rainer Maillard and Sydney Meyer, are remarkable. I only own one original German pressing from this set, the Mother Goose/Le Tombeau (2530 752) released in 1975. By the standards of other DG records of the day, this is actually a pretty good sounding record on its own. It lacks a lot of the hard string tone and washed out wind sound that many of its contemporary peers possess. Only in the larger dynamics does the original pressing get hard and brittle, but that is a problem solved by these new reissues.

All four of these recordings were produced by Thomas Mowrey who by the early 70s had become Deutsche Grammophon’s “go-to” man in Boston, with lead engineer Hans-Peter Schweigmann acting as “Tonmeister” with assistance from Gernot Westhäuser and Joachim Niss. Throughout my experience with both 70s DG pressings, as well as with recordings reissued via the Original Source label, I have found the Boston recordings to be sonically the best of the bunch. A lot of this may have to do with the remarkable acoustic environment, however given that these recordings sound noticeably better than the earlier 4-track Abbado Debussy/Ravel disc (reviewed here), the team involved may also have something to do with it.

All of the recordings (with I believe the exception of one side), were recorded to 8-track tape. This means Emil Berliner were able to use their recently built passive mixing console to cut these records. My copies, pressed at Optimal as always, were universally flat and free of audible sonic defects. The cutting choices by Sidney Meyer were also superb as I never felt as if the music was crammed too close to the label or cut with any dynamic limitation. In fact, the dynamics on these records will shock you, particularly on the Bolero/La Valse disc, which will soon become one of my new reference albums for reviewing equipment.

Maillard and Meyer have been able to coax out of these tapes the acoustical magic of Boston Symphony Hall, and because of the mic’ing setup DG were employing in this era, we have a very nice combination of spot-lit detail from the multiple mic configuration, and hall ambiance with a “tail” (reverb decay) that is incredibly balanced in length.

Ravel’s orchestral music is a must-own for any respectable classical collection, and the great performances and reference-level sonics in this 4LP box make it any easy recommendation for exploring this music. Sure, you could absolutely expand your horizons with many other great renditions of this repertoire on vinyl, but that would merely add additional color to what is already a standout achievement, and in reality, you won’t miss much if these are the only Ravel recordings on your shelf.

.png)