The Complete Sound of Music Soundtrack

All the Music and Then Some

Next year the movie version of The Sound of Music will be sixty years old. Perhaps in anticipation of the anniversary, this past December Concord Music, which acquired the Rodgers & Hammerstein Organization in 2018, released what it calls The Sound of Music—Super Deluxe Edition, through Craft Recordings, Concord’s label devoted to reissues of classic and legacy recordings. According to Mike Matessino, the Los Angeles based film-music historian and preservationist who spearheaded the project, “the newly mixed and remastered collection offers the complete film score, plus previously unreleased instrumentals, alternate takes, demos and much more, including rare vocal recordings from the cast.”

Inasmuch as the soundtrack of The Sound of Music has never been out of print since the RCA LP of 1965, the year the film opened, and has been reissued countless times in the decades since, including the first CD in 1985, it’s fair to ask what this set contains that isn’t already available, apart of course from the extras and what value they have, not to mention exactly who the market is. Adding to the confusion is the fact that Craft has simultaneously released some of the Super Deluxe’s contents in four other configurations. Perhaps the best way to address these questions is to heed the advice of Oscar Hammerstein himself: Let’s start at the very beginning, a very good place to start . . .

The Original Cast

I assume no one reading this needs to be told that The Sound of Music originated as a theatrical musical, the last collaboration between the composer Richard Rodgers and the lyricist Oscar Hammerstein, a partnership that began in 1943 with the pathbreaking Oklahoma!, coursed through eleven musicals over the next seventeen years that included their three other masterpieces, Carousel, South Pacific, and The King and I, and ended with Hammerstein’s death nine months after The Sound of Music opened on Broadway in November 1959. Despite the fact that it was a huge hit there and even bigger abroad, notably in London, most people know the musical only from the phenomenally successful movie version. Yet for the first six years of the musical’s existence, when people imagined Maria and the Baron von Trapp, they saw not Julie Andrews and Christopher Plummer, the stars of the movie, rather Mary Martin, who developed the project, and Theodore Bikel. Martin, who had starred in the original production of Rodgers and Hammerstein’s South Pacific ten years earlier, brought them the “package,” as it’s called in the trade, as a vehicle for herself.

Mary Martin and Theodore Bikel

Mary Martin and Theodore Bikel

The story is set in Salzburg 1938, several months before the Anschluss or “annexation,” Hitler’s euphemism for the invasion of Austria. Maria, a young postulant of common origin, too high-spirited for the life of a nun, is sent to be the governess for the seven children of the widowed Baron von Trapp. Since the death of his wife, Trapp’s feelings have become more or less frozen, even toward his children, whom he loves very much though running the household as if it were a military academy, forbidding the pleasures of music and musicmaking. Maria teaches them to sing, brings music back into the house, and falls in love with the baron and he with her. Soon after the marriage, the family flee Austria owing to Trapp’s outspoken defiance of the Nazis. The musical ends with their flight to safety.

In the decades that followed, the actual Trapp Family Singers became a world-famous singing group, settling in America; Maria wrote a memoir; and a German film company made two movies about them, all of which were drawn upon for the musical’s book, written by the Broadway veteran team of Howard Lindsay and Russel Crouse (I believe this is the only Rodgers and Hammerstein show for which Hammerstein did not write the book). The story they fashioned is in broad (very broad) outline substantially true but in detail considerably altered, fabricated, or completely fictionalized. A close examination of the differences between history and book is beyond the scope of this review, but a few differences between the theatrical version and the film require some comment.

Mary Martin was twenty-five years older than the actual Maria when she became the Trapp governess. Martin just about got away with her age owing to a combination of her physical fitness and the physical distance between audience and performer in most theatres, a distance obliterated by the camera in a movie theatre. I never saw Martin on stage, but when I listened to the original cast recording I was struck by how much older she sounds: often tremulous and effortful, shortcomings she managed to put at the service of the character. Strictly in terms of the listening experience, it’s fascinating to hear how her mezzo, as opposed to the much younger Andrews’s bright bell-like soprano, and her fragility make the character more nostalgic, even reflective, and tamps down some of the breathlessly energetic joyfulness that characterizes much of the film.

Another reason you might want to begin with the original cast album is that turning book into screenplay, Ernest Lehman eliminated the two songs sung by characters outside Maria and the Trapp family, feeling they had no place in the story, even as he retained the characters who sing them. In the first, “How Can Love Survive?,” Max, the impresario who comes up with the idea of the Trapp Family Singers, asks Elsa, the baroness whom Trapp plans to marry, why the baron hasn’t yet proposed, and proceeds to answer his own question by suggesting, in some of the wittiest lyrics Hammerstein ever wrote, it’s because they’re too wealthy to be authentically romantic:

No little cold water flat have we,

Warmed by a glow of insolvency,

Up to your necks in security.

How can love survive?

How can I show what I feel for you?

I cannot go out and steal for you,

I cannot die like Camille for you.

Hammerstein once said that he was not by nature drawn to irony. But this song, among many throughout his long career, surely demonstrates otherwise, as does the other one, the most political in the show, “No Way to Stop It,” where Max and Elsa, trying to convince the baron to accept the inevitable, celebrate compromise and capitulation in the face of the imminent Anschluss:

You dear attractive dewy-eyed idealist,

Today you have to learn to be a realist.Be wise, compromise.

Compromise, and be wise!

Let them think you're on their side, be noncommittal.I will not bow my head to the men I despise!

You won't have to bow your head to stoop a little.

Why not learn to put your faith and your reliance,

On an obvious and simple fact of science?

Removing this took with it Trapp’s psychologically richer, more principled reasons for rejecting Elsa in favor of Maria and all but completely eliminates any reference to the widespread cynicism by which many tried to justify cowardly or otherwise deplorable behavior during those terrible times. Jettisoning these songs also left composer and lyricist even more vulnerable than they already were to charges of schmaltz, sugar, and sentimentality.

But it helped that Lehman also dropped “An Ordinary Couple,” in which the baron and Maria sing of their desire for a life of simple domesticity, a drab tune with trite lyrics (“We'll meet our daily problems/And rest when day is done,/Our arms around each other/In the fading sun”), which nobody seems to have regretted losing. Martin and Theodore Bikel could play ordinary, but by the time the movie came out, Andrews had won her Oscar for Mary Poppins and Christopher Plummer was on the verge of stardom. Whatever else they were, neither was in least ordinary and certainly not when projected in widescreen Todd-AO (yet another reason the original stars didn’t do the movie). It was replaced by “Something Good,” in which Maria and the baron declare their love for one another. Hammerstein was a few years dead by the time Rodgers had to write this song, so the composer wrote the lyrics as well.

Julie Andrews and Christopher Plummer in the sole romantic ballad in the show.

Julie Andrews and Christopher Plummer in the sole romantic ballad in the show.

As he also did for a song newly composed for the movie. Both Lehman and the director Robert Wise felt they couldn’t just make a hard cut from Maria at abbey to her arrival at the Trapp villa—something was needed to dramatize her pluck and courage in the face of fear at taking on the job of governing seven children, and it had to be in the form of a song. “I Have Confidence in Me” became that song. Covering as it does the montage of Maria’s long walk, suitcase and guitar in tow, from the abbey to the villa, it fit in very well with what might be called the “travelogue” numbers that proliferate the first third (of a three-hour film): the title song, the newly composed Overture (the play had none), the religious music in the abbey, a long instrumental postlude to “My Favorite Things” that segues into the “Do-Re-Mi” montage that telescopes the many weeks of Maria’s developing relationship with the children.

"I Have Confidence in Me"

"I Have Confidence in Me"

The Original Soundtrack

Like most film soundtracks, the one for The Sound of Music is far from complete.[1] In the case of the original LP and CD releases of The Sound of Music, this translated into sixteen cuts or tracks, all of them songs, plus the Overture, the only instrumental on the album. Also left out were the reprises of several songs, except for “Climb Every Mountain” at the end. The songs were taken directly from the soundtrack.

In 1994 Twentieth Century Fox’s music department discovered that the original 35-mm music stems used for the final dub were shedding.[2] Immediately, they were backed up to 2-inch 24-track tapes. When the 30th anniversary laserdisc of the film was released, a companion soundtrack was issued on CD by Fox Music; at about the same time, Sony, which had acquired the RCA label, released its own 30th anniversary legacy CD, and in the years that followed various additional CDs were issued with extras such as some of the reprised songs, an instrumental piece or two, a few interviews, all digitally remastered in some way or other. But these “extras” served only to leave Mike Matessino “hoping that one day this recovered 3-track album master and the backed-up multi-channel studio scoring masters could be merged to create the definitive expanded release of The Sound of Music. It took three decades.”

The Definitive Soundtrack

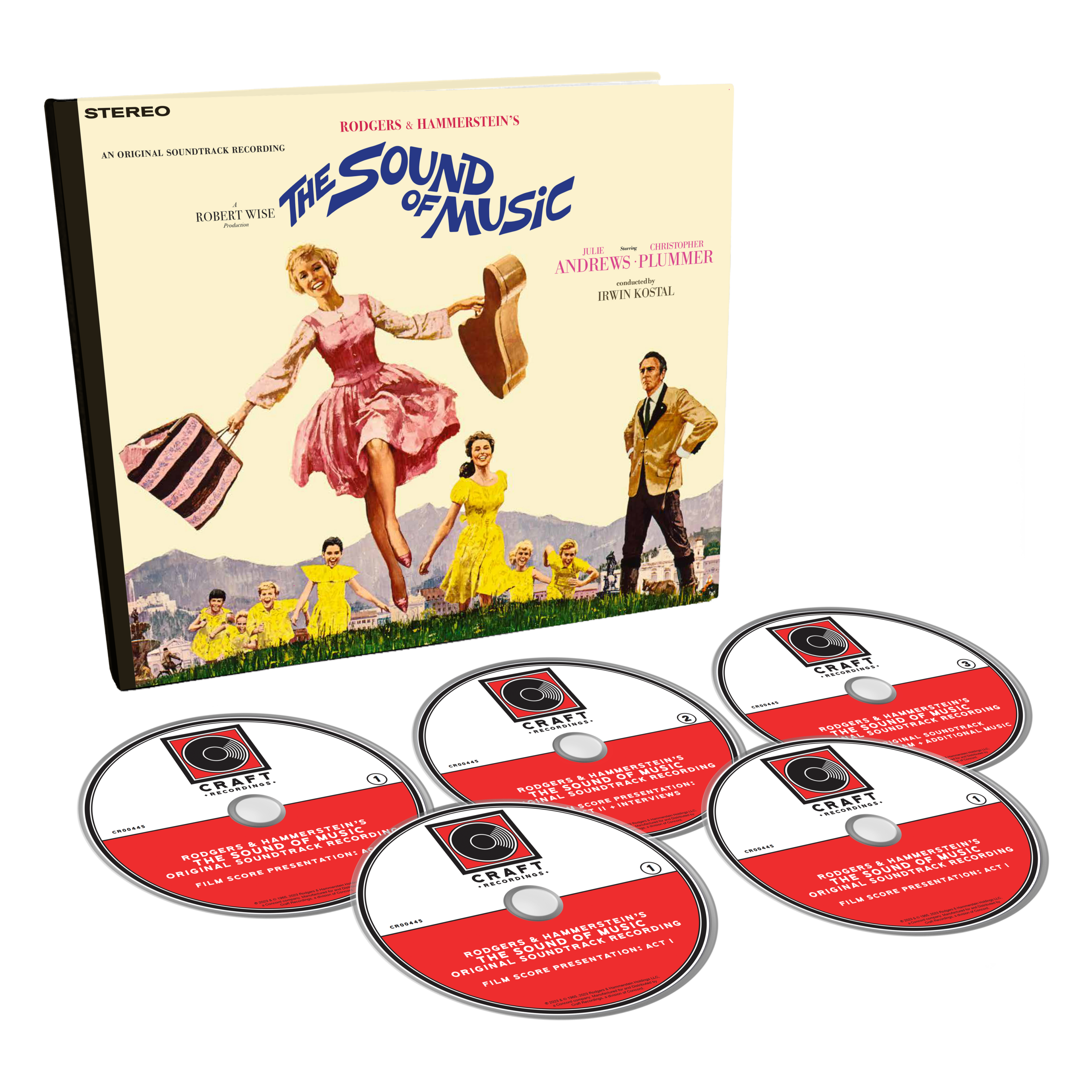

According to my Webster’s, “Something definitive is complete and final.” In those terms, Craft Recordings’s Super Deluxe set comes about as close as anything I’ve run across. The presentation is impressive, as it should be given the $109 price: an oversized 64-page hardcover book, written by Matessino himself,[3] full of behind-the-scenes and archival photographs, movie stills, and an outstandingly informative critical appreciation, another on every song and instrumental number (including how they are used in the film, when and where they were recorded, and all the lyrics), and several additional notes, bursting with pertinent anecdotes and technical and historical information about the filmmaking. An ardent enthusiast of The Sound of Music and a friend and sometime colleague of the film’s director Robert Wise, Matessino considered this project a “sacred duty.” If that strikes something of a melodramatic note, what cannot be gainsaid is his conviction and dedication. He has here set a new standard for the way things like this should be done if they’re to be done at all. (How I wish the corporations who own the great classical catalogues were similarly comprehensive—in many of their boxes you’re lucky you get a full list of the performers!)

The Sound of Music: Super Deluxe Edition

The Sound of Music: Super Deluxe Edition

Here’s a rundown of the contents.

· CDs1&2: Film Score Presentation, Acts I (CD1) and II (CD2). This includes every musical element from the film for the first time in a commercial release: every piece of underscore, transitional cue, and sting, counting some underscore written but never used, and separate instrumentals for the songs, along with interviews with Richard Rodgers Robert Wise, and Charmian Carr (who plays Liesl, the oldest of the Trapp children). As a point of reference, the total number of tracks for the Film Score Presentation (not counting the interviews) is forty-six, thirty more than the original soundtrack album.

· CD3 contains only the sixteen tracks from the original soundtrack album, plus four additional items (one of them a demo of “I Have Confidence” sung by Marni Nixon).

· CD4 contains alternates and playbacks. This is a little confusing. The playbacks here are of the vocals recorded in Los Angeles, most of them before filming began. These vocals, mixed down with orchestral accompaniments to mono, were then used as playback on set so that the actors would be able to sync to the film. Although these are called “alternates,” most of them are of the vocals and instrumentals in the final mix. Occasionally songs and performances had to be adjusted owing to the exigencies of film production, but there was relatively little of that on this film. Included are three tracks where Plummer attempted his own singing (never used in the film). Filling out the disc are the instrumental charts for all the songs without the vocals, in stereo.

· A Blu-ray audio disc contains the Film Score Presentation from CDs1&2 in 24/96 resolution and the original soundtrack from CD3 in a Dolby Atmos mix.

Realizing that the full monte of the Super Deluxe Edition might be more than even many enthusiasts might want, Craft has also issued the Film Score Presentation as a two-CD set ($25) and as a 3-LP vinyl set ($75), both sans book and all other extras (the LP box includes one of the essays from the book). There is also a hi-res digital download that includes most of the additional audio contents of the Super Deluxe ($40) and a standard digital download of the remastered original soundtrack ($10). (Announced but as of this writing not yet available is a special vinyl edition limited to 500 copies pressed in “Picnic Meadow Green.”) Craft also has in its catalogue a vinyl edition of the original RCA soundtrack (1LP, $26) and the original Broadway cast (2-LP, $38). Plainly the consumer has a lotta ways to go with this music.

The Sound of Music: 3LP gatefold album

The Sound of Music: 3LP gatefold album

The Film Score Presentation

The main attraction here is obviously the Film Score Presentation on CDs1&2 and the Blu-ray. This is something I don’t believe I’ve ever seen before: the entire musical track of a film-musical soundtrack, in story sequence, only stripped of all dialogue (except those numbers where spoken lines are interleaved with the lyrics) and all the diegetic elements from the final dub. What Matessino has fashioned puts me in mind of that genre of classical music often called “opera without words,” whereby operas are condensed into suites or fantasies with vocal parts assigned to instruments.[4] What the Film Score Presentation gives us is a film musical without the film, that is, without the images and dialogue, thus to some extent unencumbered by a story too saccharine for many to tolerate. (With “No Way to Stop It” MIA, you’d never know the Nazis figure in the story!)

Perusing the tracks listing I wondered if even the hardest of die-hard fans would want to listen to a lot of this stuff. Does anyone really want to listen more than once on its own to “The Little Dears,” a 33-second “humorous” sting for the moment Maria discovers the toad the kids slipped into her pocket? Or how about “The Governess,” the same length but never used? Then there are the various reprises of songs for dramatic or narrative purposes, never complete, sometimes as fragments. While waiting for the Super Deluxe Edition to arrive, I watched the movie, in the technologically stunning 45th Anniversary Blu-ray restoration from 2010, all the way through for the only time since I first saw it in 1965. Afterward, I was pretty sure I didn’t want to listento the whole thing again.

Nevertheless, diligence is due, so I dutifully sat down and played the entire Film Score Presentation—three times, or nearly so, in Redbook, in hi-res Blu-ray, and on vinyl. And was glad of it: first, because it was instructive, which I expected, and second, because I enjoyed most of it, which I didn’t expect. A bit of context may be necessary here. Shortly after The Sound of Music opened, it became so popular that it soon surpassed Gone with the Wind as the highest grossing movie in history, a record it held until 1972, when The Godfather topped it. It also stayed in theatres as a first-run attraction for nearly five years, a record that before or after has never been approached. In the decades since, this popularity has only deepened and broadened throughout the world. According to the trade journal Box Office Mojo, when the film was rereleased theatrically in 1990, it generated the third highest number of tickets sold behind Gone with the Wind and Star Wars; and as of 2014 its total gross admissions world-wide adjusted for inflation exceeded $2.366 billion. (As of this writing, only Avatar and Avengers: Endgame have topped that figure.)

But the critical response, both when it opened and since, was something else. Back in the mid-sixties if you considered yourself a serious filmgoer and film reviewer, then merely disliking The Sound of Music was not an option—you had actively to hate it. The so-called smart or high-brow critics like Pauline Kael, Joan Didion, Stanley Kauffmann, and Dwight Macdonald, and even some middlebrow ones like Bosley Crowther and Judith Crist all slammed it. As a point of reference, the most temperate of these pans was probably by Esquire’s Macdonald, who with imperturbable irony saluted the movie’s “perfection,” calling it “pure, unadulterated kitsch, not a false note, not a whiff of reality; and every detail so smoothly worked out . . . sparing one the slightest effort, all the seeing and hearing and feeling done for one by competent, highly paid professionals.” Meanwhile, Kauffmann called it an “atrocity,” and Kael and Didion were so vicious they eventually lost their jobs at the magazines for which they wrote. Kael’s rabid savaging in McCall’s might be the most famous (infamous?) bad review in the history of motion pictures. Outraged by what she considered the moviemakers’ shameless emotional manipulation—“Pavlovs of moviemaking” who “turn us into dogs that salivate on signal”—she accused them of treating the audience “as the lowest common-denominator of feeling”: “a sponge,” methodically, mechanically ruthlessly squeezed for response.

I proudly numbered myself among the naysayers. I even remember thinking the first time I read Kael’s review, “Yeah, go for it, slug ‘em one for me!” Now? Well, a lot can happen in sixty years. Rereading it, I found myself still in agreement with the substance of many of the points she made, but what struck me most was her feverishly jacked-up tone and her shortsightedness. Back then she believed the movie was positively harmful, even dangerous. Rechristening it The Sound of Money, she feared “it’s probably going to be the single most repressive influence on artistic freedom in movies for the next few years,” adding that its success “makes it even more difficult for anyone trying to do anything worth doing, anything relevant to the modern world, anything expressive or inventive.” Hmmm . . .

. . . let’s remember, she wrote those words in 1966. During the previous ten years some of the most promising new voices among American directors were beginning to make themselves known, directors who were about to become the auteurs of their generation: Stanley Kubrick, Sidney Lumet, John Frankenheimer, Arthur Penn, Sam Peckinpah. That same year saw the release of Whose Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, the year after that Bonnie and Clyde and In Cold Blood, 1968 In the Heat of the Night and The Graduate, 1969 The Wild Bunch, Medium Cool, Easy Rider, and Midnight Cowboy, over the next three years M*A*S*H, Little Big Man, Five Easy Pieces, The French Connection, McCabe and Mrs. Miller, Straw Dogs, A Clockwork Orange,The Great Northfield Minnesota Raid, and The Godfather, then the rest of the legendary seventies. Whatever one’s final evaluation of these films, surely no one would deny they constitute work worth doing, relevant to the modern world, expressive and inventive, not to mention serious, significant, highly personal, a few of them innovative, groundbreaking, and visionary.

As for The Sound of Music, despite its phenomenal popularity and commercial success, the astonishing thing to me is that this movie has had almost no real influence of any sort, especially artistic and commercial, on anything or anybody.[5] Except for Funny Girl (1968), most of the big-budget musicals that followed in its wake were at best middling successes, at worst flops, and none of them was well reviewed. By the early seventies, the new movie musicals, such as All That Jazz, Fiddler on the Roof, and Cabaret, were quite different stylistically, formally, musically, and thematically.

Watching The Sound of Music again, I didn’t like the manipulativeness that incensed Kael any more than I did before, but it now bothered me less. One reason, the subsequent history of films just mentioned. Another, I think, is that I was expecting it. A third is the whole matter of emotional manipulation in the arts. If you’re going to start censuring popular movies (or popular art in any medium) for that sort of thing, where do you stop? Intolerance, Potemkin, The Wizard of Oz, City Lights, A Christmas Carol, ET: The Extraterrestrial, It’s a Wonderful Life? Yes, yes, I know these works are “more” than merely manipulative while The Sound of Music is an extreme example of same, but when Kael likens its creators to “the worst despots in history, the most cynical purveyors of mass culture,” impassioned rhetoric skirts awfully close to hysteria.[6] Can this anodyne entertainment possibly be that powerful, that dangerous? My daughter first watched it when she was just past toddler age and was so transfixed by the delightful marionette show in the “The Lonely Goatherd” she watched it over and over for the next few months. (It’s one of two scenes I enjoyed most.) A couple years later, five going on six, her favorite song was “Sixteen Going on Seventeen.” Now she’s seventeen going on eighteen, into muscle cars and touring colleges, the movie is scarcely a blip on her consciousness. (Her favorite musicals are West Side Story and Sweeney Todd: The Demon Barber of Fleet Street.)

My biggest surprise this time around is how much I enjoyed Julie Andrews’s performance (more on this in a moment), so much so I thought Kael’s singling her out unnecessarily cruel and gratuitously personal. Christopher Plummer is another matter. The one thing Kael liked, she characterized him as “the spider on the valentine,” he of “the thin twisted smile.” But wasn’t this also a problem in the first half before the children’s singing thaws Trapp out? Plummer’s performance is so aloof and detached, leavened only by the occasional pinch of smug bemusement, it’s little wonder even many who love the film aren’t entirely convinced by the spur-of-the-moment conversion when Trapp overhears the children singing and before he realizes what he’s doing joins them in song. Yes, as Kael argues, you’re almost helpless not to respond to the way the scene is designed to make you respond, which leaves many of us feeling as if we’ve been programmed. But once Trapp does warm up, at least Plummer can start to play a wider of range of emotion and feeling, which actually strengthens our sense of the character’s hostility toward the Nazis because it appears focused and directed, instead of a byproduct of free-floating misanthropy toward practically everybody.[7]

Director Robert Wise and seven relentlessly adorable children.

Director Robert Wise and seven relentlessly adorable children.

What I was unprepared for was my reaction to the children, ages around six to sixteen. When I first saw the movie sixty years ago, I was a freshman just beginning college with no interest in children whatsoever, except that I felt these were all just too much—too sweet, too good, too immaculate, too beautiful. This time I found them so uniformly, relentlessly cute, so insufferably adorable that long about a third of the way in I began to fear for my insulin levels. So, without stopping the movie, I just turned off the visuals. The effect was not transformative, but at least I ceased to find them too unbearable to hear.

The same thing writ larger happened as I listened to the Film Score Presentation. Without the visuals, without the story, I found myself enjoying much of the music for long stretches, beginning with Julie Andrews, on whose shoulders the album and the movie are carried. That voice really was a once in a generation phenomenon: four octaves in range (it’s said that Sinatra in his prime could manage two and a seventh—the average is 1.5-2), perfect in pitch and enunciation, impeccable in taste and judgment when it comes to phrasing, inflection, projecting the meaning, and piercing to the heart of a song. (Given that spectacular high C she tossed off at the end of “Do-Re-Mi,” it’s a pity no one recorded a Candide with her as Cunégonde.) As My Fair Lady, Cinderella, and Camelot had already demonstrated, Andrews always possessed an intuitive grasp of the idiom of musical theatre: never overtly “personal,” always, rather, in service of lyrics and character, with a straightforward delivery that never pulled a song apart or called attention to herself as performer, yet her way with rubato, stressing, weighing, or otherwise emphasizing words and phrases, always sensitive and nuanced, is masterly in its expressiveness. And what a pleasure in this day and age to hear a popular voice that has astonishing technique, flexibility, stamina, and, though light, real body, with notes that are sustained, vowels held as vowels without prematurely fading into consonants, and consonants crisply articulated. (The great choral conductor and trainer Robert Shaw used to say that “pronunciation is fifty percent of singing.”)

Julie Andrews, on whose shoulder both album and movie are carried.

Julie Andrews, on whose shoulder both album and movie are carried.

In my judgment, only two of the songs in the movie, “My Favorite Things” and “Do-Re-Mi,” approach Rodgers and Hammerstein’s best, the others an uneven assortment, despite always master craftsmanship and several decades’ worth of consummate experience in musical theatre.[8] Some of them actually get better divorced from the movie, including, “I Have Confidence in Me,” surprisingly, tailored as it was to a scene specifically created for the film. One reason might be that Andrews brought so much sheer physicality to her performance as to overwhelm the song; divorced from the visuals, the energetic delivery feels just right.[9] The title song works in either medium, Andrews dispatching its soaring melody with supreme ease and style, allowing it to deliver its goods with or without the images.

As for some of the others, “Edelweiss” is a touching ersatz folk song, full of sentiment yet stopping short of sentimentality, and so persuasive most people think it is a folk song (“You mean somebody actually wrote that?,” someone wanted to know, while the Austrian born Theodore Bikel said he remembered it from his childhood, which was decades before it was written). It’s nice to have the lovely duet version between the Baron and Liesl (not least for the beautiful singing of Bill Lee, Plummer’s stand-in for the vocals and maybe the best such match I’ve ever heard). The same is true for some of the reprises, notably “Sixteen Going on Seventeen,” because you get to hear Andrews sing it.

“How Do You Solve a Problem Like Maria?” has never, however, been for me solved: even were the tune better than it is, it’s a got an irritating sing-songy rhythm and banal lyrics, with metaphors that make no sense (“How do you hold a moonbeam in your hand?”—how is Maria like a moonbeam?). The big showstopper, “Climb Every Mountain,” has always struck me as boiler-plate uplift (much as I love Carousel, I don’t much care for “When You Walk Through a Storm” either, though it is much superior to “Mountain”). The children’s signature “Farewell Song,” where they sing good-bye in several different languages, had me reaching for the handset to skip to the next track.

One of the unexpected pleasures of the Film Score Presentation was the opportunity to hear unencumbered all the additional score and underscore written and arranged by Irwin Kostal, who was also the conductor. I did not fully realize, that is, I took for granted, how extensive his contribution is, how skillfully and imaginatively he wove Rodgers’s melodies and motifs into scenes without songs to express or otherwise reinforce the characters’ thoughts and feelings. Then there are the color and inventiveness of the orchestration,[10] such as the bridge from “My Favorite Things” to “Do-Re-Mi” with its two pianos, muted trumpets, and explosive snares; or both versions of the ländler, the one to which Maria and Trapp dance in the ball and the almost dulcet-like later rendition with zithers; or the two Nocturnes, delicate strings and winds, that play under the baron’s break-up with Elsa and his declaration of love for Maria, and that lead into “Something Good,” the score’s sole romantic ballad (very pretty it is). The scene with this song is the other one I liked best, Wise’s direction at its most sensitive and nuanced, especially the way he blocks the action so that it dovetails with the lovely play of light and shadow in Ted McCord’s luminous nighttime cinematography.

Despite my considerable reservations about The Sound of Music, I welcomed the opportunity this release gave me to revisit both a score and a movie I had always peremptorily dismissed. But my earlier suggestion that the film has had almost no influence on anything or anybody must be revised. In fact, it lowered a bittersweet final curtain on the career of this singularly gifted partnership, which may be why Todd S. Purdum ends his superb biography-history-critical study, Something Wonderful: Rodgers and Hammerstein’s Broadway Revolution, on a rueful note. Surviving the lyricist by eighteen years, the composer, writes Purdum, “lived long enough to see his own best work recognized as immortal but also long enough to see the musical theatre he revolutionized and dominated pass him by.” The reasons were several: second-rate, middlebrow movie versions that “minimized their shows’ sophistication and maximized their schmaltz”; concept musicals “that emphasized style over plot; and of course The Sound of Music.”

In an irony almost too rich for a Sondheim musical, the phenomenal popularity of the movie threw their collective shadow farther, wider, and longer into the future than anything else they had ever done. Yet for many in later generations it also burdened them with a reputation as a pair of square old white male sentimentalists and masters of kitsch. Measured against their finest achievements—which dealt with or otherwise referenced themes such as racism, spousal abuse, sexuality, and conflicts of class, gender, and culture—this is a cruel distortion, wholly undeserved. Whatever its value as entertainment and despite the loyalty of its millions of fans, The Sound of Music does not belong among the great musicals, by Rodgers and Hammerstein or anybody else. And by no means does it begin to suggest the lasting richness and significance, let alone the glory of their contribution to the American musical theatre.

Sonics

Given the condition of the tapes and the many sources Matessino had to draw upon to come up with the Film Score Presentation, the job was daunting. “Using the vast array of technology now available, all of the discrete orchestra, vocal, chorus and organ tracks could be worked with separately,” he writes. “Every flaw, tick, bump, drop-out and tape splice could be addressed. Synchronization and edits could be perfect; degraded material could be restored; the mixes could be worked with and revisited until they felt exactly right without a clock ticking on a studio dubbing stage.” Anyone who knows anything about audio restorations this exacting already knows that it can be done only in the digital domain, despite the fact that the original elements themselves all date from the analog age. In strictly technical terms, the results are excellent. Everything has come up sounding fresh, clean, brilliant, and transparent, with an extraordinary widening of the dynamic range. The tonal palette is on the bright side, so that the recording appears to be surrounded by a bit more air and atmosphere, while the bottom end is a little light. These are advanced as observations, not criticisms. There is not a lot of bottom end in the scoring itself (the violins far outnumber the cellos and especially the double basses, of which there are only three).

In a note that introduces the 64-page book, Ted Chapin, the former president of the Rodgers and Hammerstein Organization, writes that in all the previous issues and reissues of this music, “the orchestra always sounded boxy and old and the voices as if they were taken from somewhere else.” He asked at one point if the vocal tracks—necessarily separately recorded in a booth isolated from the orchestra for greater control over both for the final movie dub—“could be removed and paired with newly recorded orchestral tracks.” Let’s be happy nobody took him up on that, but however Matessino managed it, the singers and the orchestra really do now sound as if they’re inhabiting the same space (I assume the big recording stage at Fox Studios in West Los Angeles, a facility I am familiar with as some films I’ve edited were dubbed there), and there is a considerably widened soundstage. This gives the big numbers—like the opening, like spacious title song, or “Do-Re-Mi,” which begins in a high meadow, goes through several locations, and ends in the center of Salzburg—a very satisfying sense of spatial openness and of size and scale without robbing the intimate scenes, like the one surrounding “Something Good,” of requisite intimacy. Perhaps the most remarkable aspect of Matessino’s work throughout is that the results evince none of that “processed” sound which sometimes afflicts restorations as complex as this one.

Regular readers of mine already know I withdrew from the digital/analog war a good while ago, the two technologies long since having achieved parity. If you’ve sold all your records in favor of digital all the way and you really love this music, my suggestion is you spring for the Super Deluxe set because it includes the Blu-ray, which gets you the Film Score Presentation in high resolution 24/96. My Blu-ray player is an Oppo BD-105, and the superiority, not huge but there to be heard, is evident as regards transparency, color, and a subtle sense of more detail. But the Redbook on CDs1&2 is very close, and there are circumstances under which you might prefer it, to wit: I am currently reviewing Luxman’s new D-07X, a player that by the designers’ own admission has been voiced to sound a little on the smooth, pleasing, natural side. Sometimes I preferred the Redbook discs through the Luxman to the Blu-ray through the Oppo.

Which brings us to the new vinyl release, which contains the Film Score Presentation only. Despite a stray tick or three the surfaces are blessedly quiet; and since Craft spreads the program over six sides with some of the most generous run-out areas I’ve ever seen, a good 1.25” from the spindle, there is no increased distortion and reduced dynamic range in the inner grooves. Sonically, the tonal balance is pretty close to that of the CDs and Blu-ray, in fact the overall sound of all three is closer than I would have expected in transparency and dynamic range. I often find that vinyl has a difficult-to-define dimensionality and roundedness that can elude digital media; to the extent that is true here, the effect is relatively subtle. Is it worth worth $50 more than the Film Score Presentation by itself on two CDs? I can’t answer that for you. I was glad to hear both; in sonic terms, I like them both. Saying which, the allure of the special qualities of vinyl will always tempt some audiophiles of my age, much as the song of the Sirens does Odysseus.

One thing more: if you’re really into vintage vinyl, I would urge you to pick up a copy of the original cast album. Out of curiosity I found a vintage six-eye Columbia in near mint condition on Discogs for $13.00 delivered. This was recorded in 1959 with all-tube analog equipment on tapes nowhere beginning to deteriorate, and the sound is gorgeous: warm, rounded, dimensional, tactile. It’s right up there with the original cast West Side Story from the same period (for all I know, the same studio and personnel), some of the most beautiful sonics of any original cast recording. Original pressings of the RCA movie LP are also widely available (albeit a lot more expensive), with similarly appealing vintage sonics.

[1] The thinking of the marketers, and often the composers themselves, is that all most people want are the songs; adding anything else would require an extra LP or CD, thus raising the price and potentially reducing sales. This is even truer of soundtracks of movies that aren’t musicals. With many of those you don’t even get the actual recordings used in the film. Inasmuch as the musicians’ union requires that musicians be paid for every discrete use to which their recordings are put outside the film proper—in other words, it costs almost as much to issue a soundtrack without rerecording it as it does to rerecord it—many composers just go ahead and rerecord it, often rearranging and tightening it and/or taking advantage of the extra sessions to get better performances. (When movie soundtracks are recorded, the musicians typically are seeing the music for the first time the day of the session; their only rehearsals consist in a couple of run-throughs of each cue, which means the recordings are essentially the result of sightreading, a skill at which studio musicians have to be expert.) Further, many composers don’t want their scores released in their entireties because they regard cues such as transitions, stings, brief underscores merely functional to the specific use in the film, not something they’re comfortable having out there in the world on their own (Jerry Goldsmith, with whom I was once privileged to work, hated when studios allowed his scores to be released in full).

[2] In shedding, the binder that holds the oxide particles to the tape begins to deteriorate and the particles fall off the tapes. Left uncorrected, the tapes eventually become unplayable, the recordings lost. The most common fix is baking the tapes (literally, in an oven), but this is a temporary fix. Once baked, the tapes can be copied and thus the recordings preserved.

[3] A trained musician, music mixer, and music editor, Matessino has participated in the restoration of hundreds of soundtracks, many of them A-list pictures by such composers as John Williams, Jerry Goldsmith, Bernard Herrmann, James Newton Howard, Thomas Newman, and Alan Silvestri.

[4] Matessino informed me that he did almost the same thing with the expanded film soundtracks of Doctor Dolittle and Goodbye, Mr. Chips.

[5] Including Robert Wise, who turned immediately to his next project, The Sand Pebbles, a hard-edged, powerful adaptation of Richard McKenna’s prize-winning historical novel about a US gunboat patrolling the Yangtze River in China of the twenties (one of the first movies, by the way, to reflect America’s involvement in Vietnam).

[6] I wish she had furnished a few names. Those in my own personal gallery of evil all used the traditional tools: divisiveness, hatred, racism, xenophobia, intimidation, threat, and violence.

[7] Virulent opposition to Nazi rule is the principal thing the Trapp of the musical has in common with the real Trapp, who was the very antithesis of a cold martinet, instead a warm, caring, even indulgent father, who adored his children, doted on them, and encouraged their musicmaking. Maria loved the children no less, but she was the true disciplinarian and taskmaster in the family; overprotective to a fault, she carefully monitored and limited the children’s social activities outside the household well into their young adulthood, especially when it came to members of the opposite sex.

[8] I would also put “How Does Love Survive?” and “No Way to Stop It,” missing from the movie, among their best.

[9] In Andrews’s defense, the filmmakers, in particular the associate producer Saul Chaplin, had to keep prodding Rodgers to make the song longer because they needed it to cover a montage; eventually, Chaplin himself, a trained musician, had to cobble together additional lyrics from different sources (the title song’s verse, never used in the film, drafts of Lehman’s screenplay). Andrews, who wasn’t informed about any of this, found the resulting lyrics something of a hodge-podge that made little sense to her. Deciding that Maria’s nervousness about the job interview “works herself into a state and becomes a bit dotty . . . I started flinging myself about, skipping and swinging and tripping over my suitcase to make it seem as if I was babbling with nerves.”

[10] The orchestrator of the theatrical musical was the great Robert Russell Bennett, most of whose work is used in the movie, but so many of the songs were reordered with so much internal restructuring of the action that Kostal had to write a lot of new material while restricting himself to what Rodgers had composed and the style of Bennett’s orchestrations.

.png)