DS Audio DS-E3 Optical Phono Pickup and DS-E3 Equalizer

DS Audio's new entry level optical cartridge is state of the art in some key areas.

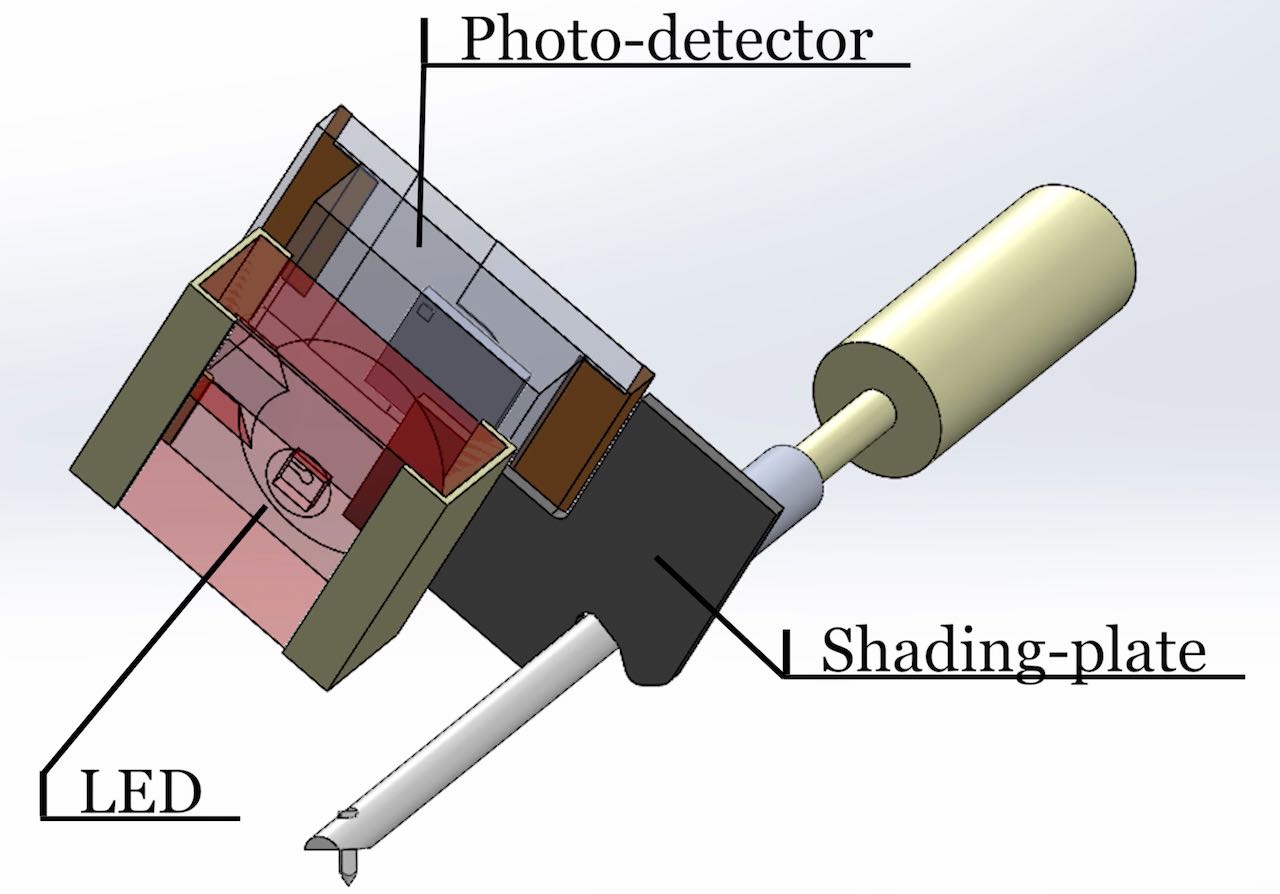

Until recently I’ve had no personal experience with DS Audio’s cutting-edge optical phono pickups, whereby the signal is generated from a pair of infra-red LEDs that shine onto photo detectors, completely dispensing with magnets and coils, moving or stationary. In their place, between the LEDs and the detectors, is a very lightweight shade, plate, or, to use DS’s parlance, “shading plate” attached to the cantilever; this shade modulates the amount of light from the LEDs it allows to reach the sensors as the stylus tracks the grooves. Despite the use of LEDs and photo sensors, it can readily be seen that DS pickups, like all other phono cartridges, still track the groove with a stylus attached to a cantilever in a system that is wholly analog. This is a very simplified description of some highly sophisticated technology. For a deeper dive, I refer you to the DS Audio website, which contains a detailed description refreshingly free from puffery and hype, including a nice graphic video that really is worth more than a thousand words: https://ds-audio-w.biz/info_optical_cartridge/.

Exploded view of LED, shading plate, cantilever, and photo detector

Exploded view of LED, shading plate, cantilever, and photo detector

I’ve been reading nothing but choruses of raves for DS pickups—extravagant even by the standards of the typically excitable audiophile press—since they first appeared in 2014 (my review of the original was among, if not the only negative one, wherein DS had not yet effectively dealt with the equalizer frequency response issue_ed.), so when Garth Leerer of Musical Surroundings, DS’s importer, asked me if I’d like to review the new entry level model, the E3, he didn’t have to ask twice. I shall anticipate my conclusions by saying right off that in some key areas of vinyl replay the E3 is superior to every other pickup with which I’ve had any sort of long experience regardless of type, technology, or price in over a half a century of pursing high-end audio. I’ll come to those anon. But first some practical matters.

Nuts, Bolts, Equalizers, and Setup

The principal difference between DS Audio’s pickups and conventional ones is that owing to the way the signal is generated, it is driven by amplitude rather than velocity. Again, this is a simplified way of stating a complicated matter (conventional pickups are both velocity and amplitude driven). But in practical terms, it means that DS pickups cannot be used, indeed will not work with the RIAA equalization in all phono stages, nor do they need the step-up devices of low-output moving coils. Instead, every DS Audio pickup requires an outboard device the company calls an equalizer, which supplies a line-level signal that is plugged into a high-level input on a preamplifier or integrated amplifier. The output of the pickup itself is amazingly robust, easily surpassing moving magnets and high-output moving coils.

.jpeg)

E3 Phono Equalizer fore and aft

E3 Phono Equalizer fore and aft

Otherwise, just like all phono pickups, DS’s demand the same care with overhang, offset, azimuth, tracking weight, anti-skating, and height adjustment. The E3 benefits from a good bit of trickle-down improvement from the upper models, including its third-generation mechanism, higher output owing to independent LEDs and photo diodes for each channel, and beryllium for the shading plates, which are far, far lower in mass than any magnet or coil. The cantilever is tapered aluminum, the stylus “solid elliptical” (DS do not state the material). The more expensive models use more exotic, thus pricier materials and geometries. As for the E3 equalizer, the circuit is now symmetrical and an operational amplifier replaces the discrete parts of the more expensive models. Cosmetically, the rather generic chassis of the E1 equalizer gives way to the E3’s larger, more stylish one with its extruded fascia. The pickup itself sports a nifty green light that while unnecessary for operation is there to let you know the pickup is in fact receiving the voltage without which there would be no sound (if the equalizer is turned on and no light illuminates on the cartridge, something is amiss somewhere).

On the rear of the chassis are one pair each of inputs and outputs. The latter has a two-position switch: position 1, called single cut-off, reducing the output below 30Hz by 6dB per octave; position two, called double cut-off, reducing the output below 50Hz by 6dB per octave and below 30Hz by 6dB per octave. Because the system does not require the extreme RIAA compensation in the low bass, all other things being equal, position 1 is the default. If the bass proves too ample with that setting—DS say that with some large ported-loudspeakers this can happen—position 2 is encouraged. The sonic differences between the two are audible enough that I wish DS had put this switch on the front panel.

At the recommended 2.1-gram downward weight, tracking is excellent. Not quite in Shure V15 league or maybe some of the better Ortofons, but nothing to fret about either. Arm compatibility is excellent as well. I used the E3 in three different tonearms: SME’s M2-12R, Ortofon’s new AS212-R, and the SAEC arm that comes with Luxman’s PD-191A turntable. It performed outstandingly in all of them. From both my (limited) experience and what I’ve been to gather, one of the nice things about DS pickups is that they are not terribly arm sensitive so long as the arms are of at least medium mass. To be sure, like any fine pickup, a better arm will get more out of them, but in this case arm compatibility is more important. Of my three arms, I liked it best in the SME M2-12R, because its high mass (effective mass 28 grams), very well damped, and extremely low in any sort of friction (another reason may be that it’s a 12-inch arm).

DS Audio sent along their own HS-001 head shell, which uses the standard SME-type bayonet connector. At $450 this is may seem rather pricey, but that’s relative. Several manufacturers now offer after-market headshells, at least one approaching the thousand-dollar mark. Although I’ve never used that one, I have tried a number at prices comparable to DS’s and can report that it is far more beautifully made, machined from Duraluminum with hand-soldered Litz signal leads and weighing in at 10.5 grams. Unlike many headshells, it has aligning pins on both the top and bottom of the bayonet, which helps fix it more securely at the connection (though it is not the only headshell with this feature). Comparing headshells is not my idea of a good time, being rather fraught with uncertainty owing to the time it takes to unmount the pickup in one arm and remount it in another, not to mention all the other variables, such as mass, materials, wiring. Something else the HS-001 eliminates is the thin rubber washer at the connection end, this presumably for a more rigid coupling. I’ve tried this on other headshells that have this washer, which is most of them, and the results are inconclusive at best. Sometimes there’s an improvement and sometimes there isn’t. DS feel comfortable eliminating it because, I assume, they feel the HS-001 is so well damped, so low in resonance, and so tightly connected that rigidity brings no penalty in obtrusive resonance or the lack of what damping the washer may provide. Here’s what I can say with some confidence: the HS-001 is better than the stock head shell that comes with the SME arm, at least with the E3 and my reference moving coils, which also sound fractionally cleaner and more controlled. (But this must be decided on a pickup-by- pickup basis: depending on everything from the high-frequency resonances endemic to all moving coils, the materials used in the pickup body, cantilever, wire, not to mention the arm bearings, materials, damping, armboard—well, you get the idea. (For what my experience may be worth, when in doubt I keep it in place inasmuch as some damping is rarely a bad thing.)

HS-001 headshell: note the bottom pin in addition to the top one and the absence of the rubber washer at the connection end.

HS-001 headshell: note the bottom pin in addition to the top one and the absence of the rubber washer at the connection end.

A few years ago DS Audio made the decision to allow other manufacturers to make phono equalizers for DS’s pickups. As of now, there are six companies who make optical-cartridge compatible equalizers: Soulnote, EMM Labs, Uesugi Labs, Meitner audio, Soulution, and Westminsterlab. According to DS, their “main goal” in allowing this “is to make the optical cartridge, which is currently a ‘unique’ cartridge, a ‘popular’ cartridge along with MM/MC cartridges as a third cartridge.” It makes a lot of sense, notably when you factor in the typical audiophile prejudice in favor of specialization. Many audiophiles feel that transducer designers are incapable of designing electronics as good as electronics designers. This is a way to attract audiophiles who want more flexibility of choice. I’ve not heard any of these competing products.

The Sound

There are at least four areas of vinyl playback in which the DS Audio E3 performed better than other phono pickups in my experience: transparency, including the related areas of clarity and resolution; transient response; dynamic range, including the related areas of lower noise and perceived distortion; and imaging and soundstaging.

I started where I often start when I evaluate equipment, something simple, direct, pure, and beautiful, in this case Jacintha’s cover of “Sweet Baby James” from her collection of James Taylor songs for Groove Note (45rpm). This is a supremely transparent recording to begin with, but with the E3 her voice is reproduced with an immediacy, presence, and purity that are rather startling. The way first the guitar, then the violin steal in gently, sweetly at the end of her solo is exquisitely delicate and lovely.

Writing about transparency for us reviewers is not easy because what we’re trying to describe are things that are lacking, missing, absent, or otherwise not there, things like veiling or the subtler forms of haze, grain, distortion, and noise. This means the process is necessarily comparative—even equipment from the lower end of the audiophile marketplace has reached a sufficiently advanced state of transparency that we often don’t notice the subtler forms of veiling until they’re gone. Of course, when these are inherent in the recording, they can’t be reduced away, but the better transparency of the E3 is readily audible, even when it’s not by much and even with non-audiophile recordings.

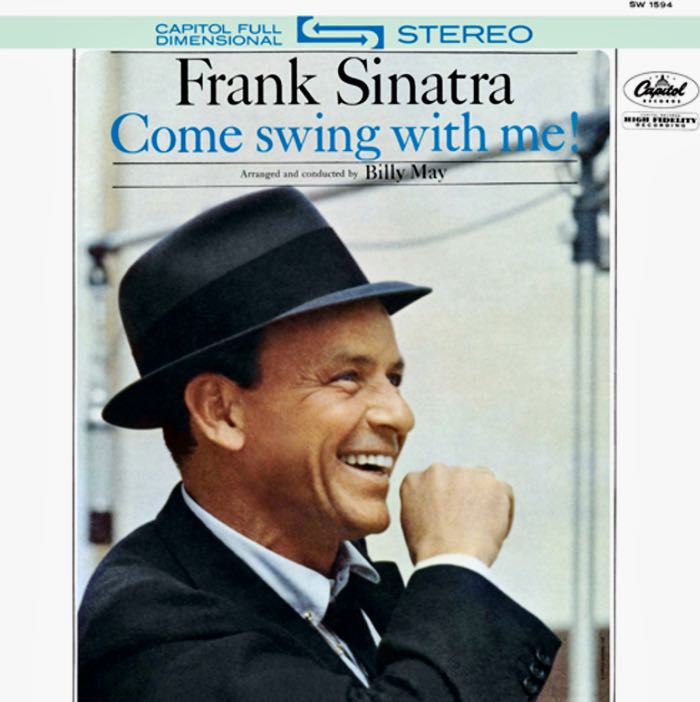

Take the Sinatra/Billy May Come Swing with Me (Capitol)—there’s Sinatra front and center, again with reach-out-and-touch him immediacy, while May’s antiphonal brass—this 1961 recording was made when stereo was still relatively young, his arrangements designed to exploit the right/left extremes of the new medium—leap out of the speakers with remarkable brilliance and presence. Fischer-Dieskau’s mid-fifties EMI recording of Winterreise, with Gerald Moore on piano, is recorded differently from the Sinatra. To start with, it’s mono, and there is no attempt to be audiophile impressive, singer and pianist set discreetly back a bit so you have more space them and you. The effect is less immediate in terms of presence but more realistic as regards an approximation of what you’d hear in a good recital hall, and certainly no less transparent. This great singer's nuances of phrase, subtleties of inflection, sureness of intonation, intelligence of conception, depth of feeling and emotion are superbly conveyed with wonderful sense of involvement.

Clarity and resolution are functions of transparency. For the sake of discussion, clarity to me refers to the ability of a sound system to reproduce musical ensembles and textures of whatever simplicity, complexity, thickness, density, or number such that the individual instruments and voices are audible if they’re supposed to be or blended if that is the desired effect. If a component is too analytical, then the presentation can feel picked apart and not fully coherent. Richard Strauss once said that he never intended all the notes in his music to be heard; sometimes they were there merely to contribute to an overall effect of richness and saturation. Few conductors understood this more than Herbert von Karajan, of which there are few better examples than his early-seventies recording of Death and Transfiguration and Four Last Songs (with Gundula Janowicz), recently reissued as part of DG’s Original Source Series LPs. While this is not a state-of-the-art recording, Karajan’s signature goals of smoothness, blend, and gleaming sonority are in abundant evidence. But go to George Szell’s equally fine performance with the Cleveland Orchestra (vintage Columbia) and you find a conductor who wants everything to be heard. Both recordings, interestingly, are somewhat light in the bass, an anomaly for which the E3 compensates (more later on this), but the Karajan has more bloom, the Szell is drier (as was his wont—many of Szell’s recordings are light in the bass and dry).

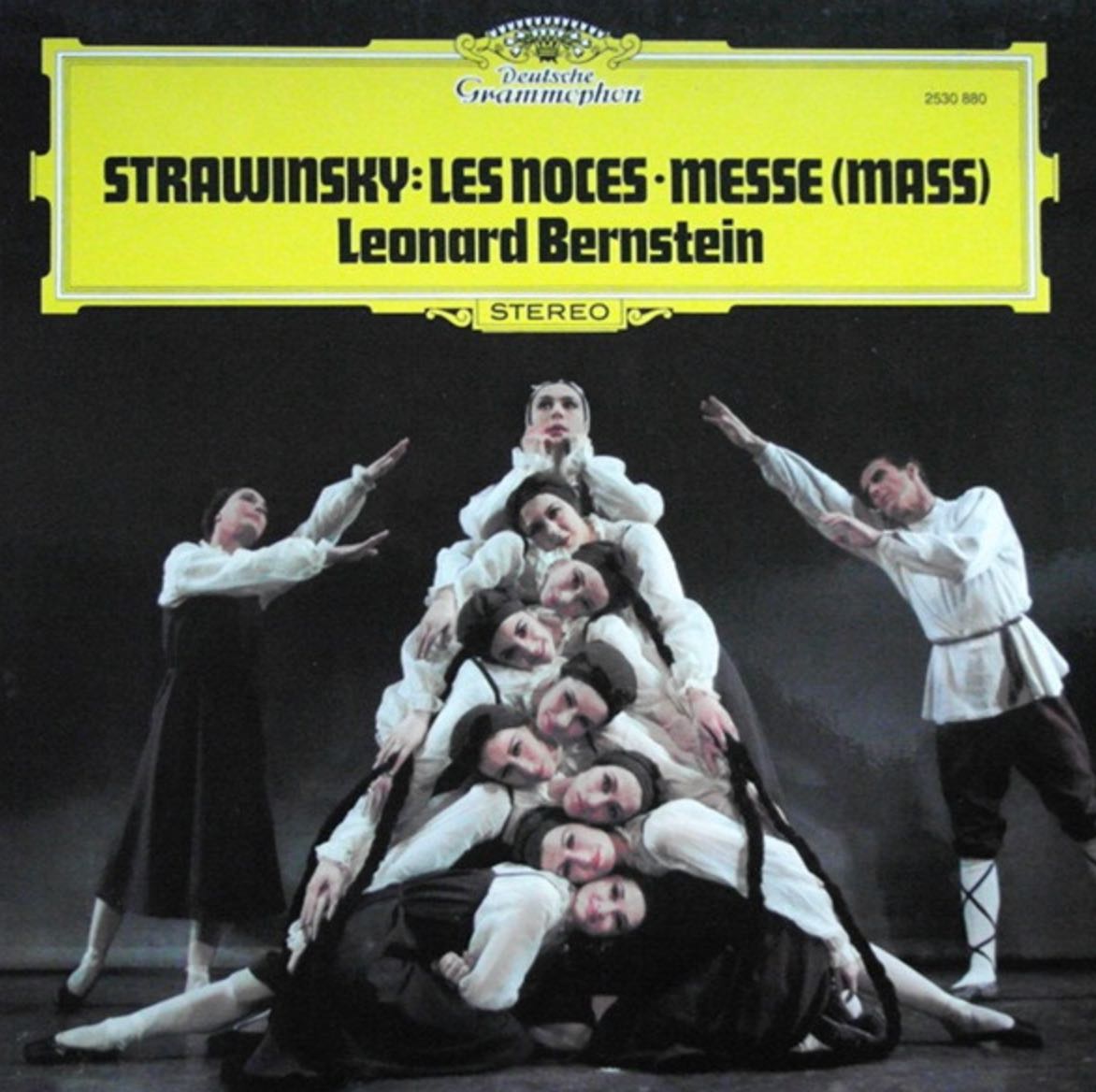

Unlike Strauss, Stravinsky typically wanted everything to be heard and articulated. I pulled out Bernstein’s late seventies DG analog recording of Stravinsky’s Les Noces (the greatest piece of music Carl Orff never wrote, said one wag), a cantata depicting a Russian peasant wedding for four soloists, a chamber choir, four pianos, and percussion (timpani, bass drum, snare drums, antique cymbals, chimes, cymbals, tambourine, triangle, and xylophone), 4 pianos, mixed chorus, and soloists. This is a spectacular recording in every respect, notably in dynamic range but also in the registration of the instruments, particularly the pianos and the percussion. With four pianos furiously playing patterns of rhythms, while soloists and chorus are virtually declaiming the text as percussion slashes, bangs, pounds away, this is a difficult piece to record. But DG’s engineers really delivered the goods to thrilling effect with plenty of detail (bass drum really impressive) that never detracts from the gestalt, and the E3’s presentation is sensational. It’s also impressively controlled: when the big, sharp percussive hits come they don’t momentarily obliterate everything around, under, or above them.

My standard test for detail and resolution as such is the “Moon River” cut on Jacintha’s Johnny Mercer album. Way back in the late nineties I was at the recording sessions here in Los Angeles when this track was laid down. She wanted to sing the introduction a cappella, a specialty of hers (she does the same with “Sweet Baby James”). To this end, she was isolated in a soundproof booth as the pianist/arranger played very soft chords transmitted through headphones to enable her to stay in tune. But every time a chord was sounded, it bled through her headphones and was picked up by the very sensitive microphones. Mind you, these chords are extremely, almost vanishingly low in level, so much so they completely vanish on many systems (including some very pricey ones I’ve heard) and they disappear on any system if the playback is low enough. All of my reference pickups will reproduce most and sometimes all of these, but the E3 is the only one that retrieves every last one of them at a volume level lower overall that what I typically need to use (I suspect Ortofon’s Anna Diamond did as well, but I reviewed it several years ago and no longer have it around, so I can’t be sure).

Common wisdom has it that all other things being equal elliptical styli reproduce transients less precisely than more advanced geometries like line-contact. Well, okay, but you couldn’t prove it by me when it comes to the E3. The panoply of percussion in Stravinsky’s Les Noces is loaded with transients the E3 reproduced with hair-raising impact and precision. Or try Impex’s astonishing Saturday Night in San Francisco, a live recording of the virtuoso guitarists Al DiMeola, John McLaughlin, and Paco De Luca playing separately and as a trio. When all three play together, they are placed left, right, and center but so much of the atmosphere of crowd and venue is caught they don’t sound isolated from one another. Meanwhile, the clarity, the articulation, the resolution, and the imperturbable control are such that you can easily focus on one or another guitarist as readily as you can draw back and listen to them as a trio.

High-end audio is rife with the fallacy of arguing from effect back to cause, so while I can’t be absolutely sure it’s the considerably lower mass of the shading plates that accounts for the superior transparency and attack, it certainly stands to reason. Another, perhaps equally important, is that the absence of magnets means there’s no distortion from hysteresis, which, as I understand it, is the lag between when the signal reverses direction and the magnet in effect catches up to it—in other words, a timing error. Lack of same in the E3 is doubtless one reason why this set-up reproduces the Jim Keltner side of The Sheffield Drum Record better than I’ve ever heard before: peerless resolution and dynamic range, holographic imaging, and transient attack that sounds just right, with not a hint of bogus enhancement, ringing, hang-over, or lack of speed. It comes as close to real as I’ve ever heard it, then closer. I would draw particular attention to the way the venue is captured in this recording: what you hear is what was there, with absolutely no artificial reverb, not to mention the fact that this still sounds more authentically like a drum set and less like a recording of same than just about any other in my collection. Cymbals, high hat, wire brushes, bells, and so on are reproduced with quite breathtaking clarity, definition, delicacy, and resolution.

The E3 pickup and equalizer reproduce a three-dimensional soundstage, precision of imaging and movement within that stage, and a sense of space, air, atmosphere, and openness second to none in my experience and way better than most. Precise imaging and a continuous soundstage depend in part upon control, stability, and responsiveness to a lot of very low-level information. Right now what I regard as the best recording I know of a Broadway show, and one of the best of anything period, is John Wilson’s recent one of the complete Oklahoma! on Chandos vinyl. The precision of movement and position in this recording is uncannily realistic—you can perceive increments of a foot of space as regards depth, while the big ensemble numbers involving dancing and staging are tracked with very impressive assurance.

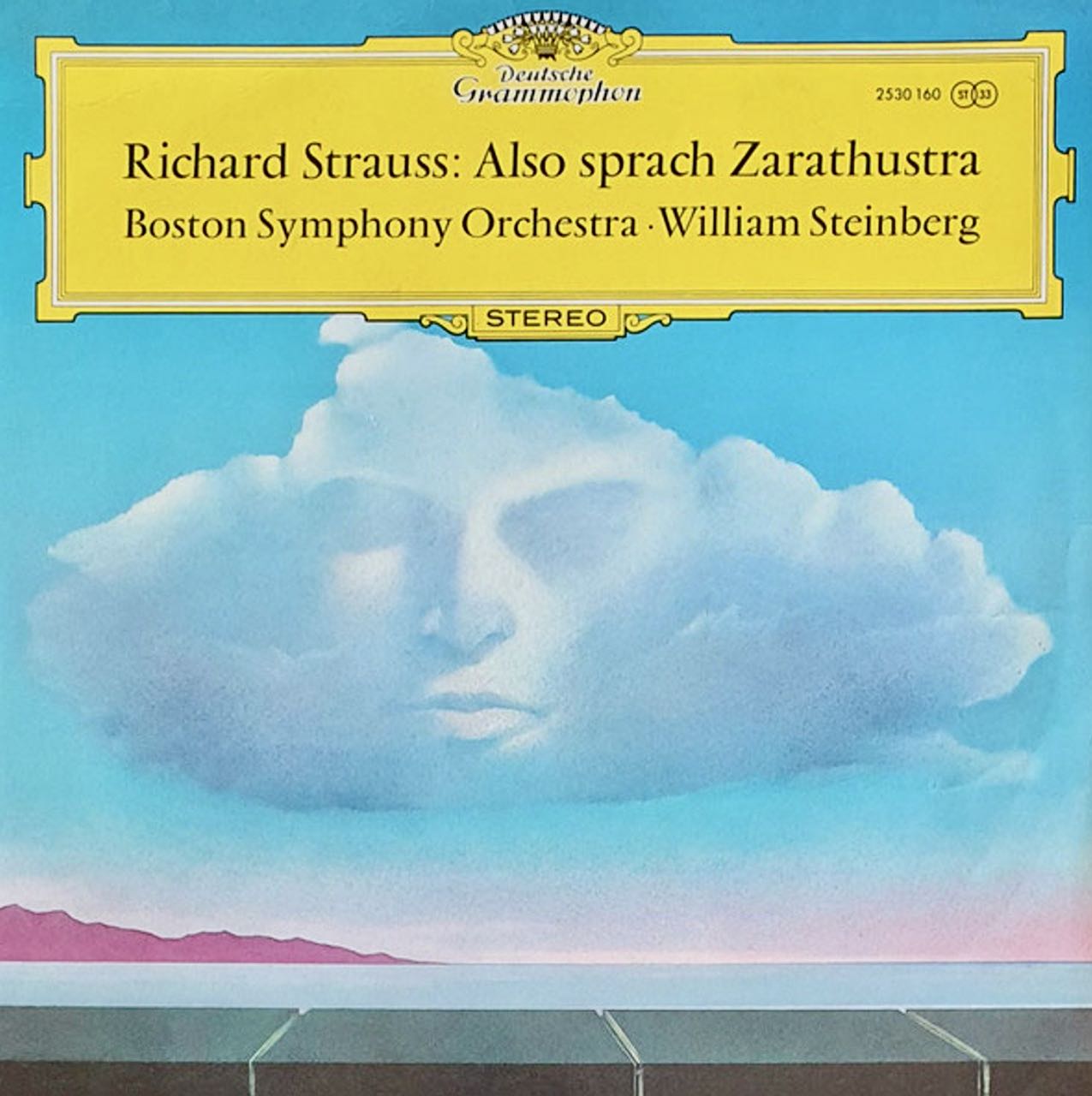

The E3 combination opens up recordings in concert halls and larger spaces in all their vastness. Again, rendition of spaces, acoustics, ambience is consistently richer, larger, more characterful than I’m used to hearing. Boston Symphony Hall, where the great Steinberg/BSO Planets and Also Sprach Zarathustra were made (DG Original Source Series), is reproduced with what strikes me as a more persuasive suggestion of its size and acoustical character than I’ve heard from most other pickups. (Many people fault the Zarathustra for being over-reverberant: I agree there’s a lot, but it doesn’t sound to me artificial.)

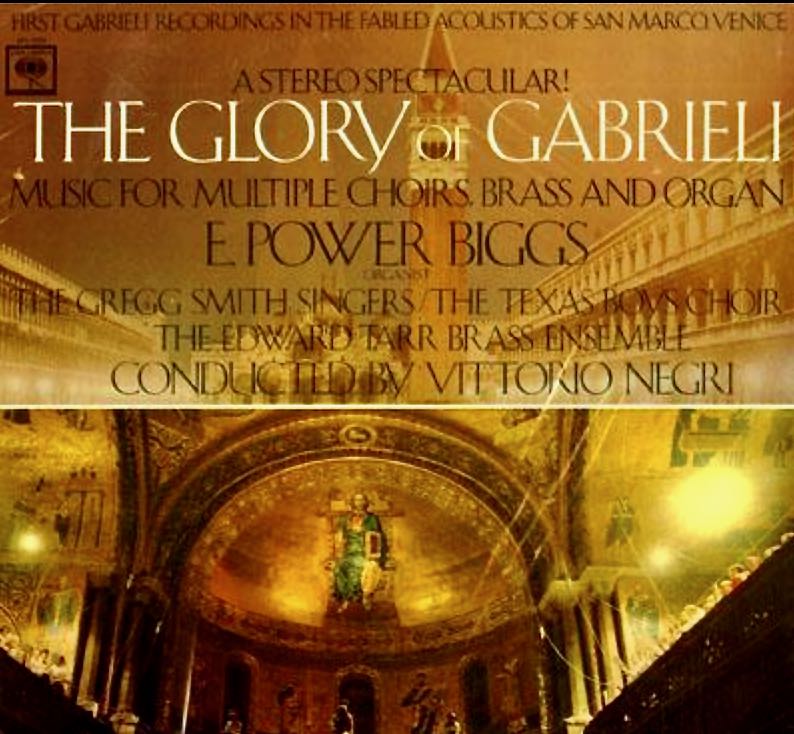

One of the largest spaces on any recording I own was made in St. Mark’s Basilica, Venice, which has some of the most legendarily beautiful acoustics in the history of music. It was here that Columbia Records, spearheaded by E. Power Biggs, carried out its classic mid-sixties project of recording choral music by the great Viennese composer Giovanni Gabrieli, who wrote these pieces with this place in mind. The producer John McClure’s spectacular recording recalls Peter Walker's idea that a good recording and reproducing system should be "a window onto a concert hall". The copy I purchased way back in college became damaged and I never got around to replacing it. Recently I picked up another in the bargain bins of Santa Monica’s Records Surplus for the princely sum of 91¢. I took it home, ran it through my Degritter, and cued it up. More decades ago than I care to number I heard a choral group I was travelling with perform here. I’ve never forgotten that experience or the sound. Gabrieli wrote these pieces for two and three choruses spatially separated for antiphonal effects, plus for organ and brass. The almost limitless sense of space, air, and atmosphere of this magnificent basilica is gloriously reproduced in all its majestic splendor.

Regular readers of mine will be aware I’ve not yet discussed tonal balance, which I regard as one of the most important parameters of audio performance. While the E3 falls within the bounds of what I call “acceptable neutrality” throughout most of its range, there are anomalies at the extreme bottom and up high. This pickup probes deeper into the grooves and excavates bass with truly impressive detail, clarity, and strength. But, as I perhaps intimated earlier, is it too much? With most music most of the time, not for me. For one thing, we are talking about only the bottom octave to octave-and-a-third of range, so you don’t have to worry about any sort of mid- and upper-bass bloat and boom. For another, it provides a welcome weight and foundation that sounds entirely right and natural. On the great Steinberg Zarathustra—one of the relatively rare recordings of this piece in which the organ’s 32-Hz fundamental is actually on the recording (another is the spectacular Decca conducted by Zubin Mehta in Los Angeles)—the opening pedal point is cleanly present and powerful in a way that rivals the best high-resolution digital. Likewise the double basses in the superb Stokowski Rhapsodies (RCA), one of his most exciting recordings, positively thrilling in reach, depth, and sheer force.

But the occasional recording does come along from time to time where the response is a little too much. Ray Brown’s Soular Energy is one such. If you compare the Pure Audiophile remastering (the one on blue vinyl) to the Groove Note SACD, assuming the latter was remastered without any tonal intervention and thus is faithful to the master tape, as I am assured it is, then the E3’s response is definitely tipped up way down there. DS’s solution is output 2 on the E3 equalizer, with its 50Hz double-filtering. This is one reason why the company provides a choice of filtered outputs (on the more expensive equalizers, the choices are even greater): while the amplitude responsiveness doesn’t need the extreme RIAA compensation for the lower levels of velocity-driven setups, it appears to require some from time to time.

Another reason I like position 1 should be obvious: it works very well in my system, as I suspect it will in most systems that don’t have bass response flat down into the last half octave. My Harbeth Monitor 40.3XD loudspeakers, for example, specifies flat response +/-3dB down to 35 Hz. With the usual boundary reinforcement, that -3dB extends down a few more cycles before it begins to drop rather precipitously. This is more than enough for almost everything in the standard orchestral, jazz, and even rock repertoire. The E3’s slight boost at the very bottom makes for a very pleasing synergy with my Harbeths, as my previous remarks about the opening of the Steinberg Zarathustra suggests. Somewhere in its literature I seem to recall the folks at DS Audio suggesting that position 1 may excite the tuning of some bass reflex systems too much. There is no such issue with the Harbeths. But if there were, the solution is to switch to position 2 with its higher threshold-frequency.

As for the top end, you’ll recall Harry Pearson’s Yin/Yang opposition, Yin being the warm, mellow dark, Yang being the bright, brilliant light. Obviously these metaphors are to be taken as suggestive rather than definitive. The E3 leans decisively toward the Yang. The first music I turn to when beginning to evaluate tonal balance consists in anything string dominated, beginning with violins. During a couple of sessions I was joined by a close friend who’s a professional violinist and also a serious audiophile. He was very satisfied with the sound of violins on some of his favorite LPs, including a lovely EMI recording of Beethoven’s E-flat sonata for violin and piano (number three) and Brahms’s in D-Minor (also the third). I never heard Oistrakh live, but what I hear on this recording—and what my friend hears—is what I’ve read about all his richness, fullness, and security of tone, not to mention his variety of weight, vibrato, and touch. For the Beethoven, the tone is a leaner, the vibrato far more chastely applied (but still applied—pace HIP fanatics); flip to the Brahms and you might think you’re hearing a different violinist, so carefully has he adjusted from the aesthetics of Beethoven to those of Brahms: richer tone, wider vibrato, more flexible manipulation of phrase and tempo, more robust over all approach and realization.

Recordings by Heifetz, Oistrakh, Milstein, and Stern were also used, as well as many recordings of string quartets (the Budapest on Columbia, the Vegh on Valois, the Alban Berg’s fabulous complete Beethoven cycle on 16-LPs from Warner) and string orchestras, beginning with the ravishing EMI recording of Vaughan-Williams’s Fantasy on a Theme of Thomas Tallis by Barbirolli and the Sinfonia of London. Likewise, Bernstein’s fantastic version of Beethoven’s Opus 131 with the full string complement of the Vienna Philharmonic (DG, vinyl—one of my desert island discs) is reproduced magnificently and with extraordinary detail that allows us to hear deep into the recording (including intakes of breath from the conductor himself).

Where the E3’s brightness shows itself most is on recordings that are already either very closely miked and/or have a rising top end for other reasons. This requires some talk. I’ve seen published measurements that show the top end rise as a pretty steep +6dB around the topmost octave and a third. But to my ears, it doesn’t sound anywhere near this steep, which puzzles me. Perhaps the explanation is that the E3 is so clean and low in perceived distortion that I find this tonal anomaly both easier to enjoy than with pickups that overall are less well behaved or are not capable of quite this transparency and clarity. Violins, for example, have just a bit of extra brilliance, but mostly only when the recording leans that way.

The Sinatra/May album is an extremely hot recording that on many systems, in particular those with rising top ends either in the phono part of the system or the loudspeakers themselves, and the brass sounds not just bright but positively edgy. I expected the same from the E3 and met with a surprise: it was bright but not at all edgy, neither unpleasant nor irritating, and in fact, I enjoyed it with great pleasure. Another explanation might be the incredibly low noise. Raise the volume to its maximum and you hear absolutely no trace of hum; normal and far louder levels result in some of the quietest, if not the backgrounds I’ve ever experienced from phono reproduction.

One thing more before wrapping up. By comparison to my favorite moving coils and moving magnets, the E3’s presentation is fractionally lacking in a certain impression of body, density, and color. I find this a bit difficult to nail down, so perhaps a comparison will help. I am a great fan of electrostatic speakers, which have been references of mine for over five decades, notably most models of Quad ESLs, some Acoustats (how’s that for dating me?), and Roger West’s SoundLabs. Yet I am far from alone in finding that one of the main areas where electrostatics yield ground to dynamic speakers, including, paramountly many horns, is precisely along these lines. Superior as the E3 is in several ways to my favorite moving coils and moving magnets, it does not exhibit quite the same degree of what for want of a better metaphor I’d call a certain “meatiness” in the presentation.

But this is only to say that like everything else in audio, it's not perfect. So that this is not misunderstood, I’m by no means suggesting the E3 is deficient in this characteristic, merely that it doesn’t possess it to the degree that other kinds of pickups do (vintage Denons and Ortofons, for example). And despite the slight rise at the bottom end, the tonal balance is by no means warm. And so that this is not misunderstood, I am not suggesting the E3 is cool, let alone cold. On the contrary, the warmth that is on your recordings it will reproduce as warmth—remember that Oistrakh Brahms—but it won’t add any of its own. Among the last things I played before wrapping up this review were John Coltrane’s Lush Life (Prestige OFC reissue), a beautiful sound that came alive in the room with all the warmth and dimensionality you could ask for, and Ben and Sweets (ORG reissue), where Webster’s rich, ripe tenor saxophone was present in all its fat, voluptuous glory.

Conclusion

DS Audio has an equalizer priced to match each pickup model in the line, but in fact any DS cartridge, from the flagship Grand Master Extreme to the least expensive, currently the one under review here, can be used with any DS equalizer and vice-versa. The consensus among colleagues of mine who’ve had the advantage of reviewing the more expensive models seems to be that if you have to economize, you get better performance mating the upper-end pickups with the lower-priced equalizers than the other way round. As a point of reference, the top-of-the-line Grand Master Extreme is $22,500, the associated equalizer $45,000 for a breathtaking $67,500 total (even without the equalizer, I think this makes the Extreme the most expensive phono pickup in the world right now). By contrast, the E3 pickup and E3 equalizer are $1375 each, for a total of $2750. By the normal standards of most people who are not audiophiles, this is pretty expensive. But in high-end audio, it almost qualifies as modest, and it’s an even better value when you consider that no phono preamp or phono stage as such is required.

The E3 phono pickup is a reference-caliber component. The areas in which it excels, even when it is not by much, it does so at a level that advances the state of the art, while there is no area in which it is less than very good to excellent. If you’re in the market for a new phono pickup anywhere near the price of this combination, I urge an audition. I‘ve been using it almost nonstop for over four months now and have not tired of it. It is a great cartridge and now one of my principal references for what is possible in the ever-developing and renewing world of analog and vinyl.

Specifications

E3 Optical Cartridge

Signal output: Photoelectric Conversion

Channel separation: 26db more (1kHz)

Weight: 7.7 grams

Output: 70mV more

Cantilever: Aluminum

Body material: Aluminum

Tracking weight: 2.0g~2.2g(2.1g is recommended)

Stylus: Elliptical

Price: $1375

E3 Phono Equalizer

Output voltage 500mV (1kHz) at equalilzer output

Input: RCA

Output: RCA

Size: 260W x 69H X 195D (mm)

Weight: 1.86 kg

Price: $1375

Manufacturer Information

Importer:

MUSICAL SURROUNDINGS

Tel: 510.547.5006

Fax: 510.547.5009

musicalsurroundings.com

.png)