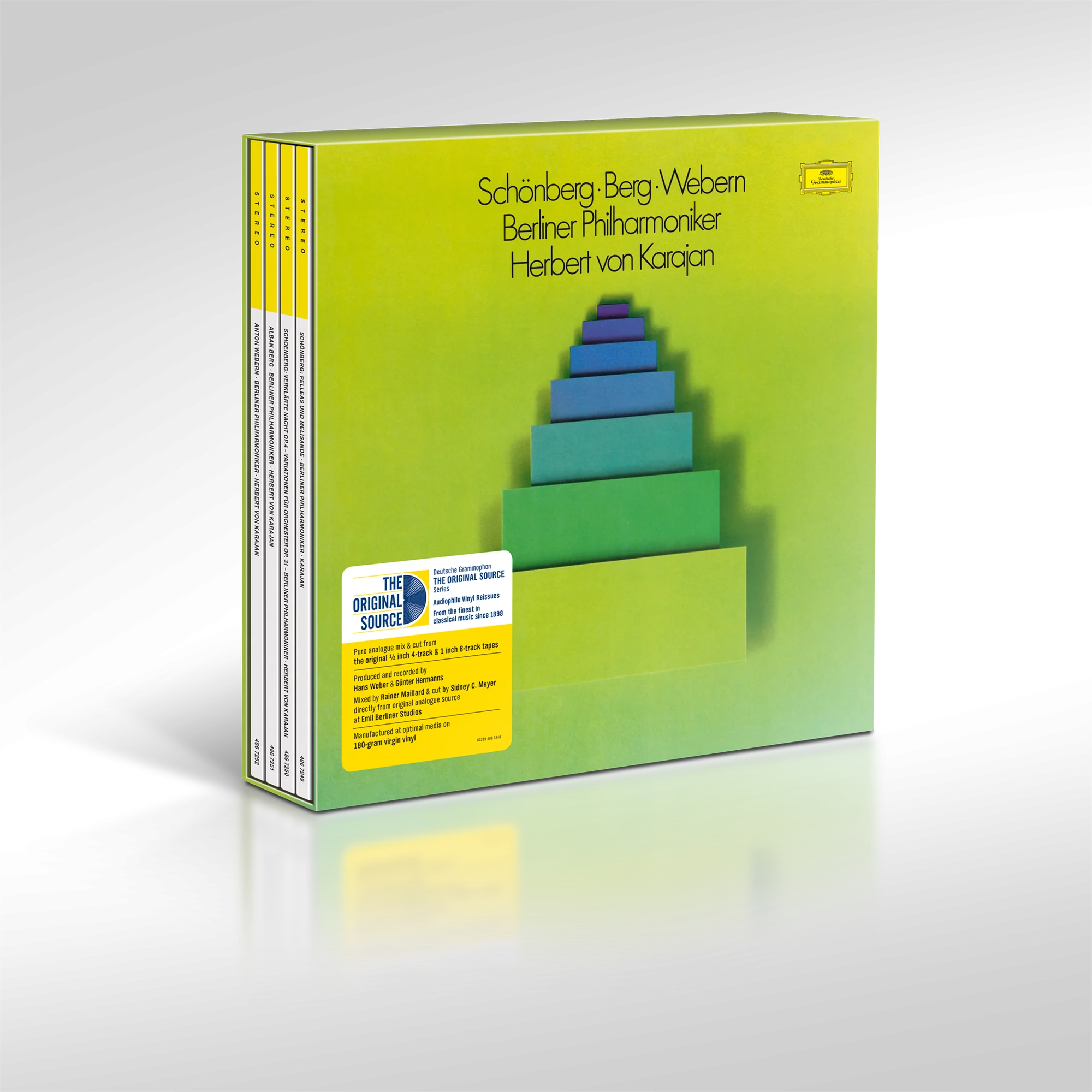

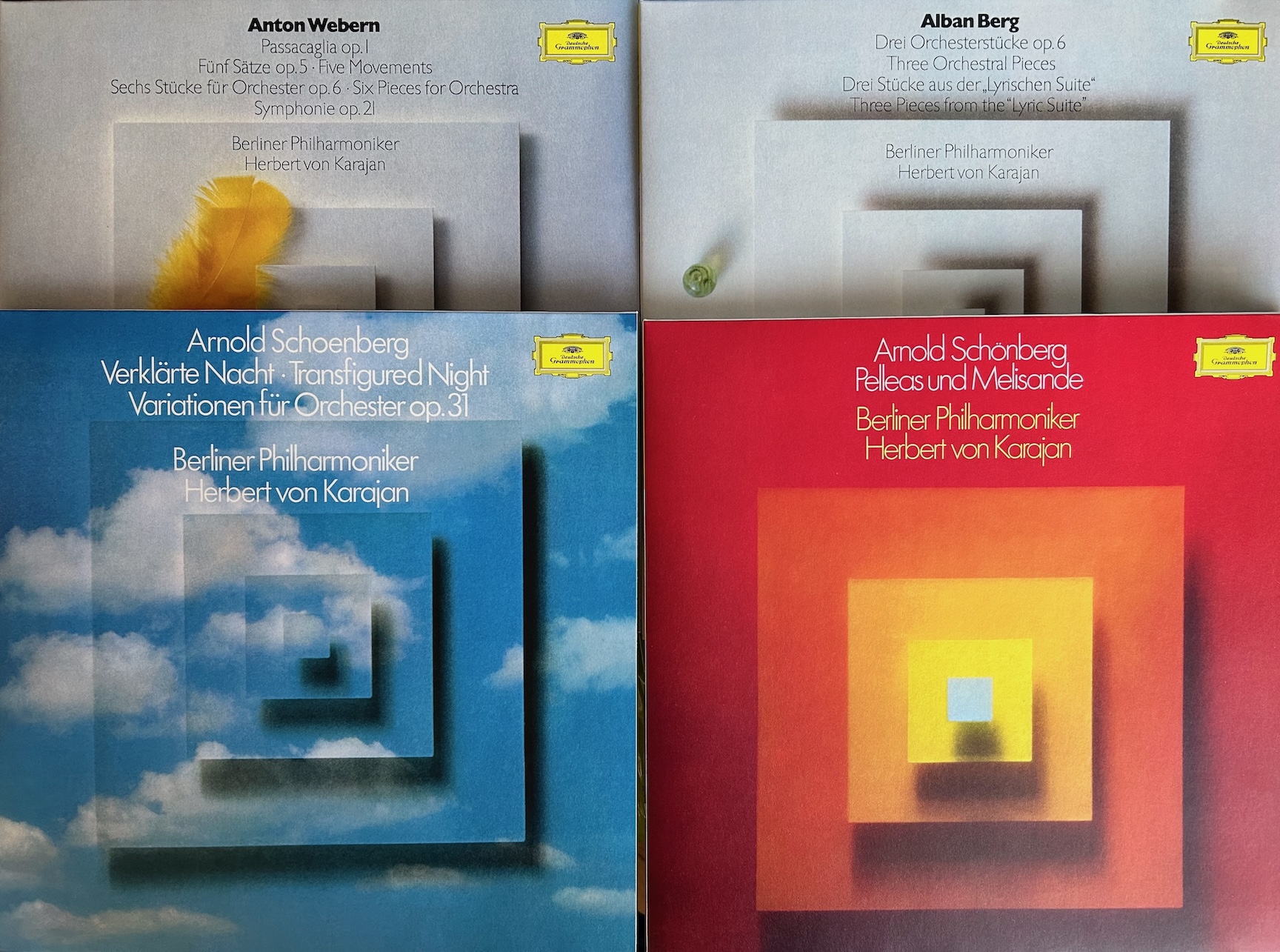

Decoding the Dawn of Modern Music - The Original Source Offers Fresh Illumination of Karajan and the BPO's Groundbreaking Survey of the Second Viennese School - PART 3

The Karajan Effect

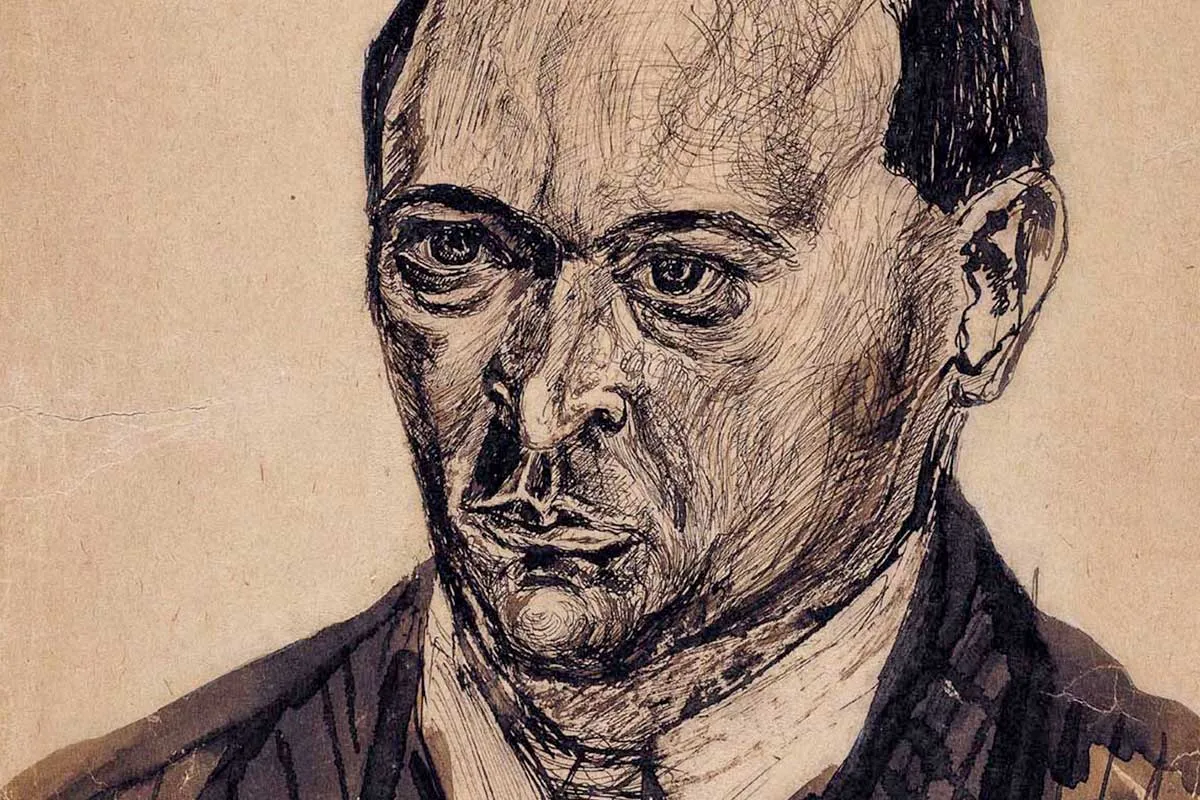

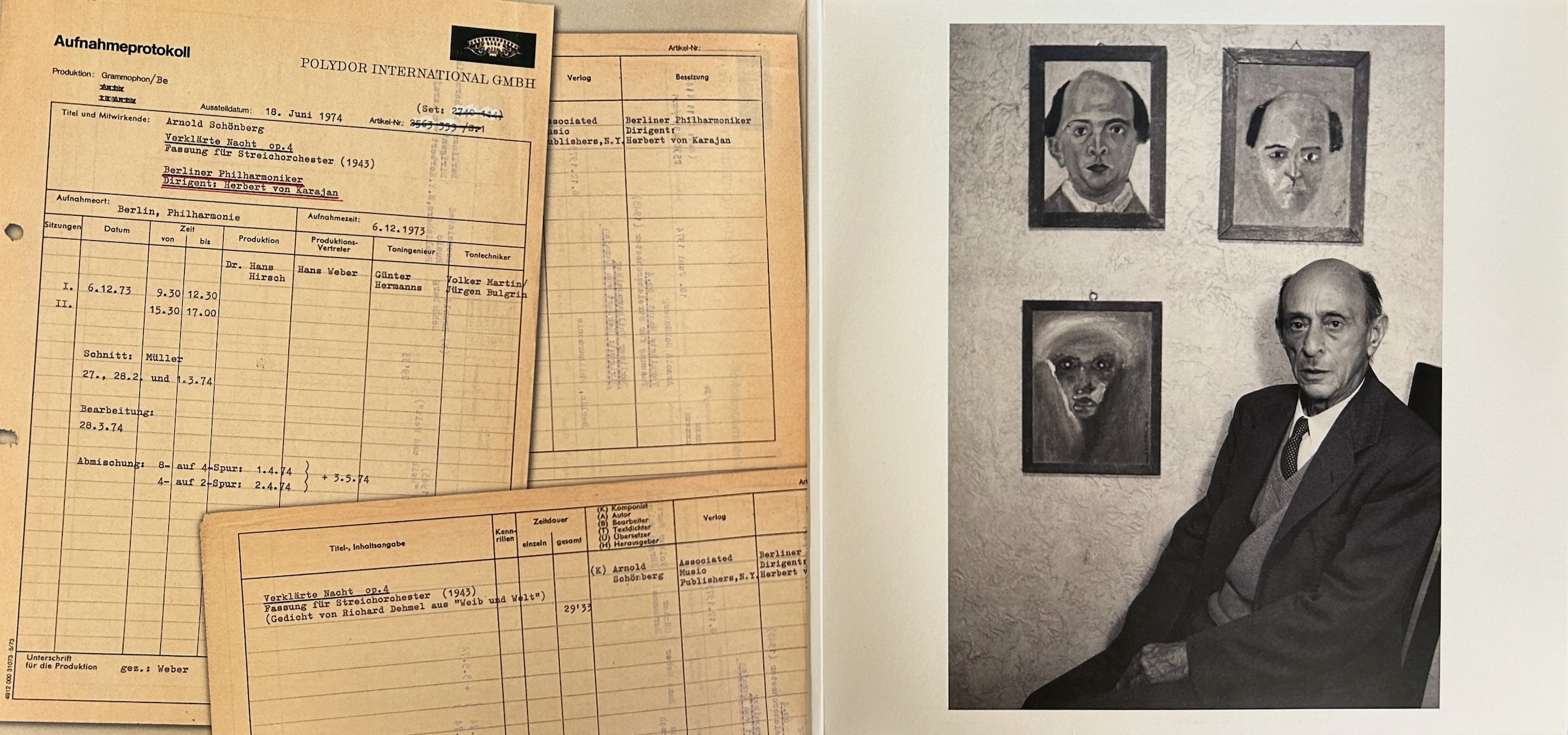

Arnold Schoenberg - Self-Portrait, 1908

Arnold Schoenberg - Self-Portrait, 1908

“I feel air from another planet.”

Text by Stefan Georg from the final movement of the Second String Quartet, Schoenberg’s first atonal piece (1908)

“I see through walls.”

Arnold Schoenberg

These two quotations tell you a lot about Schoenberg - the kind of man he was, and the kind of music he wrote.

Visionary, driven, uncompromising.

Qualities which, to one degree or another, he shared with Herbert von Karajan. There are reasons why this conductor, more than any other, dominated the classical landscape in the world’s concert halls and opera houses, and in the record bins, for some three decades, and they all have to do with those qualities.

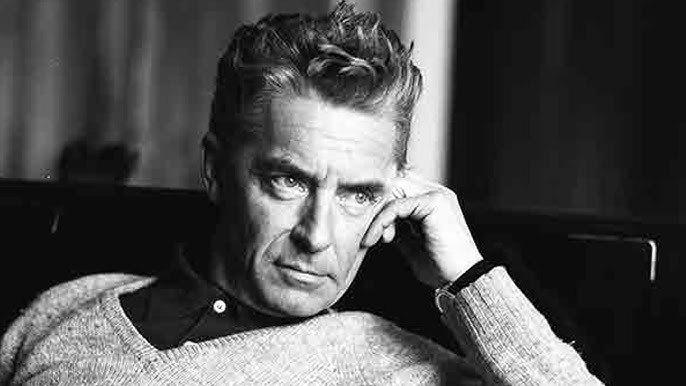

Herbert von Karajan

Herbert von Karajan

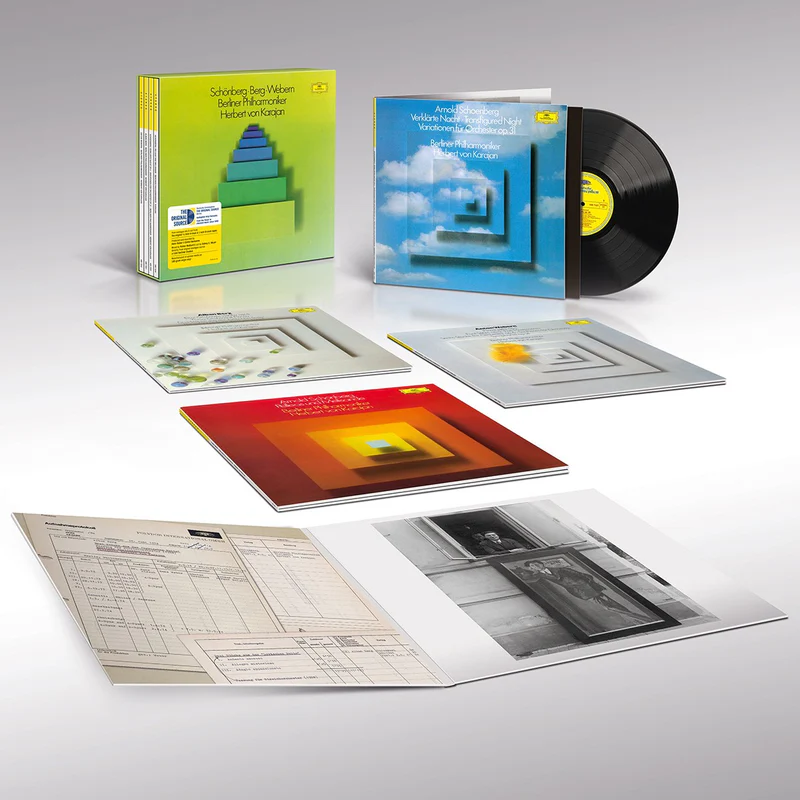

It took something of a leap of faith for Karajan to embark on this project to present four records (count them: four!) in a deluxe box set of the music of the Second Viennese School. None of this music was on anyone’s list of “must buy” records in 1974 (apart from the hardcore enthusiasts, and those were precisely the kind of listeners to turn up their noses at the prospect of any Karajan record of anything).

In the concert hall and in his earlier career, Karajan had hardly made a habit of performing this repertoire. He had, to everyone’s surprise, conducted Schoenberg’s massive Gurrelieder twice in 1967. Believe it or not, the Berliners had given the premiere of the fully serial Variations for Orchestra in December 1928 under the baton of Wilhelm Furtwängler. Karajan began working on this complex score (is any Schoenberg score not complex) in 1960, twelve years in advance of recording it.

Berg’s Three Orchestral Pieces, with its intimations of the impending cataclysm of World War I, clearly spoke to Karajan’s own childhood memories of the outbreak of that conflict. The Lyric Suite featured in his concert programs well into his twilight years, as did Verklärte Nacht. To my knowledge, Karajan never conducted Berg’s masterpiece, Wozzeck, in the opera-house or anywhere else, much to all our loss; maybe its overwrought, expressionist idiom was a mite too hysterical for his taste.

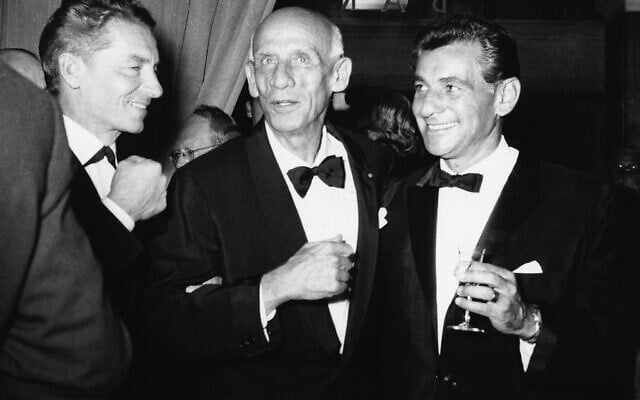

Karajan (l.), Dmitri Mitropoulos (c.) and Leonard Bernstein in Salzburg, August 1959 after a concert by the New York Philharmonic

Karajan (l.), Dmitri Mitropoulos (c.) and Leonard Bernstein in Salzburg, August 1959 after a concert by the New York Philharmonic

On a 1960 tour to New York, Karajan conducted the home town band in a program that included Webern’s Five Pieces Op. 5 (a highlight of this set). The New York Times reported that they were played with an “intense if muted romanticism” - an apt description of the present recorded performance, though a decade on from that concert that “muting” is less in evidence; in the studio the intensity is dialed up quite a bit.

David Oistrakh and Karajan after the Brahms concerto performance in Vienna, 1961

David Oistrakh and Karajan after the Brahms concerto performance in Vienna, 1961

Interestingly, at the 1961 Vienna Festival, presented at the same time as a summit meeting in the city between Khrushchev and Kennedy, Karajan prefaced a performance of the Brahms Violin Concerto featuring the great Russian virtuoso David Oistrakh with Webern’s Symphony, Op. 21. As in Schoenberg’s day, this precipitated protests from the famously reactionary Viennese concertgoers, despite Mme Khrushchev being in the audience as a guest of honor. As Richard Osborne writes in his biography of the conductor:

“Karajan was not much bothered, but Mme Khrushchev - who was clearly unfamiliar with the phenomenon of civil unrest in the concert hall - was reported to have been visibly nervous.”

In other words, much of this was music that Karajan had been working on for a while, yet had hesitated to take into the studio until he felt he and the Berliners were fully ready. This music is not easy to play, nor easy to conduct. Yes, you can get the notes, but to really drive it home needs having the music in one’s bones, and a real commitment to not only communicating the passion of the music, but its beauty - despite the forbidding surface nature of the atonal and serial works.

Because, for Karajan, this was indeed beautiful music. He had, in Osborne’s reckoning:

"... a long-standing belief that the music of the Second Viennese School was not, of itself, ugly or unapproachable. Poor technique and rehearsal time, he still believed, had been the real barriers to a proper appreciation.”

Of course the late-Romantic, tonal idiom of Schoenberg’s Verklärte Nacht and Pelléas und Melisande, albeit dense, still inhabited the perfumed, aromatic and sensual world of Richard Strauss’s highly chromatic tone poems and operas - a specialty of Karajan’s. With regard to the atonal and serial compositions in the Second Viennese School box, in a Deutsche Grammophon advertisement in the February 1975 issue of The Gramophone, Karajan was quoted thus, laying out his approach to preparing and conducting these works:

“At our many rehearsals, I repeated this again and again: ‘Gentlemen, a dissonance is a tension and a consonance is therefore the necessary and corresponding relaxation. But neither of them, tension or relaxation, can be ugly, because then they no longer constitute music any more.’ I have in mind this nonsense, which one is always hearing, that I want to ‘smooth off the rough edges’. One can only smooth off rough edges where the roughness consists of a note being played unprofessionally, ie. when it is unclean, untidy, and unattractive. In our work together we have often rehearsed the intonation for hours on end. The tension too should be a thing of beauty. The musical content must be clean and pure.”

Richard Osborne rightly makes this point:

“Karajan’s position - that a work of art, though it can express ugly emotions, cannot itself be ugly - is certainly tenable. Yet there will always be those who feel the need to run their hand across the surface of the music and sense its being rough to the touch.”

In a nutshell you have there what lends this set of performances their great strength, yet also what may be, for some, their area of weakness. In making these works so beautiful, so ravishingly and ingratiatingly “musical” rather than “clinical” (ie. romantic and passionate rather than cold and forbidding), does Karajan short-change the modernism, the rough edges that, for example in the Berg Three Orchestral Pieces or the Webern Six Pieces for Orchestra and the Symphony, give the pieces their distinctive edge? Does he compromise in some way their identity as works for the new modern age?

A good question, which I hope to answer in the course of discussing each individual record.

We begin with Schoenberg, represented in this box by his late-Romantic and tonal Verklärte Nacht (Transfigured Night) and the massive tone poem Pelleas und Melisande; then the later, fully serial Variations for Orchestra. (Alas, the essential Five Pieces for Orchestra Op.16 were never recorded by Karajan, or even performed by him, to my knowledge).

If you are going to start anywhere with this box, I recommend you start with Verklärte Nacht, an exquisite, ravishing Romantic work for strings alone that will have you melting into your listening seat. The work - in the manner of Richard Strauss’s tone poems - tells a story. It was originally composed for String Sextet, but once you’ve heard the full orchestral version you ain’t ever going back!

I’ve heard many recordings of this, including Karajan’s own live version from 1988 on Testament, which manages to be even more intense and hair-raising, albeit in sound that, while decent, hardly matches the perfumed effulgence of this new OSS version. But none comes close to capturing the many moods of this work like Karajan and the Berliners. For many, many years, this was the one record I would have chosen to take with me to a desert island.

While Verklärte Nacht might seem, on the surface, a more accessible work in the manner of Richard Strauss’s tone poems (which it is), it also marks an important moment on Schoenberg’s journey towards developing his own personal aesthetic towards composition within the context of what was going on around him in musical intellectual circles.

Remember that Schoenberg was to a large degree self-taught, an autodidact within a culture largely dominated by Conservatory and University trained musicians (as well as critics and theorists). As would be the case throughout his life, he worked his way towards strong ideas about the kind of music he wanted to write, the kind of music that would carry the art-form forward into a new century. He held these views forcefully, stubbornly, even abrasively, partly because he felt he wasn’t taken seriously by the “Establishment”, and therefore had to fight for his ideas twice as hard. This dynamic of “me against the world” was especially necessary in the highly reactionary circles of Vienna, where he spent much of his early career.

In the latter half of the 19th century, the big debate in European musical circles was between the pure “abstract” school of Brahms, working within the traditional musical forms of the symphony, sonata and concerto models, and the more “revolutionary” school of Wagner, working primarily within opera. With Wagner, the music was fed by extra-musical associations, ideas and stories, pushing it into new territory; with Brahms, the development of music within its own abstract, formal procedures was sufficient to ensure its evolution.

Beyond the opera house, that “infection” of music by extra-musical ideas resulted in the emergence of the tone-poem, in which the music told a story. It was a form pioneered by Franz Liszt and Richard Strauss, both firmly in the Wagner camp.

Extra musical ideas, even narrations, had of course made their presence felt in earlier music: various symphonies of Haydn (eg. “The Clock”, “The Hen”), Beethoven’s 6th Symphony, known as the “Pastoral”, and, most tellingly, in the Symphonie Fantastique of Berlioz from 1830, in many ways the work that - because of its subjective, "programmatic" elements - announced definitively the arrival of the Romantic period in classical music.

Schoenberg himself, in his earliest works, seemed to identify more with the Brahmsian school, rather than the Wagnerites. But all that changed with his discovery, in 1898, of the poetry of Richard Dehmel.

.jpg) Portrait of Richard Dehmel by Max Liebermann (1909)

Portrait of Richard Dehmel by Max Liebermann (1909)

Dehmel sought to reconcile the inherent contradictions contained within apparent opposites like male-female, subject-object, god and nature, light and dark. He strived to combine notions of the individual and the universal in a form that would bring about cultural and aesthetic change.

All of this can be seen clearly in Dehmel’s poem that was to provide the “program” for Verklärte Nacht. Two lovers walk in a forest: the woman, in a state of high anxiety, reveals that she is carrying the child of another man; her partner, instead of rejecting her, embraces the arrival of new life, and declares his undying love; the two are reconciled and the night is transfigured.

Many years later in 1912, Schoenberg wrote to Dehmel:

“For your poems have had a decisive influence on my development as a composer. They were what first made me try to find a new tone in the lyrical mood. Or rather, I found it even without looking, simply by reflecting in music what your poems stirred up in me.”

In other words, the poem helped Schoenberg find a way to integrate his more innovatory instincts (the Wagnerian mode) with the more traditional Brahmsian model he had been following hitherto.

In an excellent program note for the L.A. Philharmonic, archivist Steven Lacoste illuminates the processes of this piece far better than I could ever summarize, and I think his analysis is worth reprinting here:

The over-all form of the poem Verklärte Nacht is obvious enough in its ABACA structure, wherein A functions as a refrain in which a narrator describes two people walking. The B section consists of a woman informing a man that she is pregnant (by another man), while C recounts the man’s response. The symmetry is classical in design and, as with all classical structures, contains the duality of conflict and resolution. However, the conflict inherent in this text is not so much resolved but, as the title suggests, it is transfigured. The poem does this by raising the two protagonists to a higher level of humanity, indeed to a greater unity based upon sympathy and compassionate understanding.

For what really occurs in this poem is a celebration of new life, both literally and figuratively. The process by which this happens is through a kind of mystical impregnation or, better still, interpenetration of a human warmth from the woman into the man and vice versa. As the man states: ‘But a special warmth flickers/From you into me, from me into you./It will transfigure the strange man’s child.’ The woman and man have radically transfigured the artificiality of societal convention to merge with a radiantly confluent universe.

Schoenberg’s musical setting follows the large form defining sections of the poem faithfully. However, just as the woman and man have transcended the moral taboos of bourgeois mores to form a new unity, Schoenberg has created, in the inner workings of his material, not a musical mirror of the poem, but a “new tone in the lyric mood.” The program of the poem, indeed the poem itself, becomes, in the Wagnerian sense, a metaphor for what music can express immediately and essentially without the mediation of language. Schoenberg achieves this realization through the interpenetration and juxtaposition of themes identified with the woman, man, and narration respectively, with the Brahmsian technique of thematic variation and development. In this way he not only expressed the idea of the poem but, perhaps in a more profound way, an expression of himself ‘simply by reflecting in music what your poems stirred up in me.’ With this work Schoenberg resolved, at least for himself, one conflict, the Brahms/Wagner controversy.

Verklärte Nacht is overwhelming, as vivid a statement of “Love Conquers All” as you will find in any work of art.

The work had particular resonance for Schoenberg, since when he started composing it in 1899 he had met and fallen in love with Mathilde Zemlinsky, sister of the composer Alexander von Zemlinsky, who was Schoenberg’s teacher. They married in 1902.

Mathilde Schoenberg with their daughter Gertrud

Mathilde Schoenberg with their daughter Gertrud

The work opens almost imperceptibly, with an evocation of the woodland scene which engineer Gunter Herrmanns and Karajan somehow transform into Shakespeare’s magical isle in The Tempest:

“…the isle is full of noises,

Sounds, and sweet airs, that give delight and hurt not”

After the slow churning chords in the lower strings that pull back the curtain on the scene, listen out for the entrance of the high violins, dropping fairy dust, their tutti giving way to first desk soloists. We are in “Once upon a Time” territory here. No other recording captures this ineffable moment like this.

Throughout, Karajan’s long experience as an opera conductor of the first rank is in evidence, able to balance the needs of a long dramatic arc against the push and pull of individual moments of dramatic tension. Also his skills as a great Brahms and Strauss conductor enable him to fully illuminate the inner textures of the dense string writing. This new remastering not only provides an all-enveloping, three-dimensional soundstage, it allows you to listen deeply into the complex string lines. Needless to say the string sonorities, encompassing both delicate solo work and pile-driving tutti, are golden hued and simply ravishing.

After the tumult of the opening sections where Karajan and the Berliners never hold back from fully dramatizing every emotional ebb and flow - the almost overwhelming force of the woman’s turbulent anxiety, regret and fear of rejection - the moment at which the man’s forgiveness is fully articulated (in a radiant major chord) resonates with particular poignancy. From there we move inexorably to the magic of the work’s peroration, articulated with a sense of awe and wonder that feels like it embraces the entire universe in music and sound of unbelievable sweetness and translucence.

This radiant end, capping 25 minutes of heart-stopping music, is truly transcendent - and transfiguring. The world seems to stop, and the night and stars become expressions of the lovers’ all-embracing love. In these final bars I always think of the vivid night skies in several of Van Gogh’s paintings - skies that in their colors and radiance seem more vivid than any sunlit landscape.

Starry Night by Van Gogh (1889)

Starry Night by Van Gogh (1889)

If you want to understand what made Karajan and the Berliners something unique in the world of classical music, listen no further than Verklärte Nacht. It is undoubtedly one of the greatest treasures in their catalogue - doubly so in this newest incarnation.

Flipping the record will bring you into a very different world. You are now entering the realm of Schoenberg’s fully serial, 12-tone music in the utterly extraordinary Variations for Orchestra, composed from 1926 to 1928.

I will never make the argument that this is easy music to listen to; in some ways it is the most demanding work in this set. But it is a piece I’ve gotten to grips with more and more over the years, and there is no doubt that the added transparency, dynamism, and orchestral richness and color gained in this remastering goes a long way towards making this a more approachable and exciting (and graspable) listen.

Besides, it’s really good to challenge ourselves as listeners.

The work was premiered by the Berliners in 1928, led by Wilhelm Furtwängler, who had already presented several scores by Schoenberg, and generally supported modern music, especially music that he felt propagated the notion of German primacy. He wasn’t so sure about the composer’s new 12-tone method, however, questioning whether it really was the next logical step in tonal development. As late as 1945, he stated that it was “the first completely unhistorical step, the first real break with history”.

Nevertheless he encouraged Schoenberg as the composer struggled to complete the work, and finally a first performance was scheduled, though with only three rehearsals - a woefully inadequate amount for a work of this complexity.

Musicologist and author Volker Tarnow at the Berlin Philharmonic takes up the story:

In his 1965 memoir, Gregor Piatigorsky, who had been principal cellist of the Berliner Philharmoniker since 1924, recalled an almost unbelievable hullabaloo during the rehearsals for the premiere of this incredibly demanding work: there was far too little time, Furtwängler went through the score bar by bar, but no one understood anything. Why didn't F-sharp major sound like F-sharp major? Why did the semiquavers look so strange? How do you perform pizzicato and bow at the same time? The next day Furtwängler appeared with the bad news: they only had one more rehearsal; and the composer would be at the concert! Now disaster loomed, and no one knew what to do. But then, at noon, partial salvation: “Gentlemen,” Furtwängler announced with relief, “I have just received the most wonderful news from Vienna: the composer is not coming.” Huge cheers, and bravos. They might not be able to save the piece, but they could salvage their self-respect. In fact, one critic praised “Furtwängler and the Philharmoniker, who in overcoming the almost grotesque difficulties of this score once again demonstrated their supreme skill”. Anton Webern, who was present in the hall, heard it differently and cabled his master to Vienna: “Unbelievable! Utterly irresponsible!

The press was unanimously negative about the work itself. “Soulless musical arithmetic”, “grotesque constructs of atonalism”, and an “incurable stubbornness” on the part of the composer, were the tenor of the journalistic attacks. Most of the audience reacted with icy disapproval, a minority hissed and whistled for all they were worth. An even smaller minority – Schoenberg’s students – wanted to forcibly bring about success through frenetic applause.

Herbert von Karajan was attending the Vienna Conservatory at the time of this premiere. In 1962 he programmed the Variations for the first time, and the work became something of an obsession for him. He came to believe that only within the controlled environment of a recording studio could the extreme performing and sonic challenges of the work be fully met. Meanwhile, he had to get the musicians up to speed, and would often rehearse fragments of the work with smaller groups of players during any extra time left over from other rehearsals or while on tour.

In the 1989 book, Conversations with Karajan, the conductor’s future biographer Richard Osborne alighted on the topic of the Variations. Karajan:

“I began the project with the orchestra several years before we made the recordings. We spent a great deal of time familiarizing ourselves with the music by playing it at subscription concerts and youth concerts. But I knew from the outset that the demands Schoenberg makes in these Variations are abnormal ones which are difficult to realize properly, even in acoustically suitable concert-halls. For the recording, we reseated the orchestra for each variation to create the acoustic that one sees and imagines when one looks at the score. Some people said this was ‘manipulation’ of the music by technology; but it is the very reverse. When Schoenberg asks for the piccolo to play ppp in the top level of its register ‘so schwach wie möglich (as weakly as possible)’ with the bassoon and solo strings at different dynamic levels, and then asks for completely different textures and dynamics in the next variation, I know that this cannot be properly realized by an orchestra in a concert-hall seated in the conventional way. Realizing the Schoenberg Variations was technically the most fascinating thing in the set.”

The results speak for themselves. I cannot think of another recording which puts across this music in a manner so alert to every nuance, every detail, with every formidable technical challenge dispatched as if irrelevant. Ally that to an interpretive thrust that is almost superhuman in its self-confidence, and you have a recording I doubt will ever be bettered. If you’ve ever wondered what serial music would sound like if played and conducted like it was Richard Strauss, this is the record to drop the needle on.

As Karajan concluded, with regard to presenting the work on record rather than in the concert hall:

“There I had the idea of the kind of sound you could never have in the concert-hall, a sound that exists only in the imagination and in the new kind of acoustic reality we were able to create through the recording itself.”

And indeed he never did conduct the work in public again.

Gatefold from the Original Source reissue, including a photo of Schoenberg with three self-portraits

Gatefold from the Original Source reissue, including a photo of Schoenberg with three self-portraits

How to find your way into this piece? I think rather than trying to discern the structure within, surrender yourself to the work’s “affect”, to what Schoenberg would say is “expressed”. One of the things that is clearly expressed is a masterful, almost surgical dissection of the orchestra, with instruments that are never normally placed together regularly, sounding both in concert with each other, and juxtaposed with each other. That orchestra includes a huge contingent of string players to balance out twenty-eight wind and brass players, plus celesta, harp and mandolin. There is a particularly extensive array of percussion used to telling effect, including the recently invented flexatone (a metal sheet with metal strikers that creates an eerie moaning sound soon to become ubiquitous in spooky radio shows, movies and cartoons). All of this is used in an almost chamber-like manner, though when the full orchestra hits it hits with a vengeance.

This is where the sophistication of the recording techniques really come into play, and the fierce dynamic contrasts are given ample room to register in the Original Source remastering. I found myself marveling at Schoenberg’s profligate abilities as an orchestrator, a quality I hadn’t consciously acknowledged hitherto.

There are moments of magic and mystery, clear from the very opening, and elsewhere sharp U-turns of mood and expression that grab you in the gut.

What you will not find, until you have listened to the work many times (and maybe not even then), is the familiar hook of melody and harmony leading you through the thicket. Instead, weird little disjointed melodic snatches, pieces of musical motives or chord fragments, will start to present themselves in different guises, and then disappear almost immediately.

You will begin to find yourself listening differently, slowly orientating yourself to this new world. It’s an almost purging experience, forcing you to confront the fundamental elements of music simply as they are, as they exist unto themselves (if that makes any sense). There will remain a distancing quality not present in the music of Schoenberg’s pupil Berg, but somewhat omnipresent in Schoenberg’s oeuvre. Is that a bad thing? I would hesitate to apply that kind of a moral judgment, as so many others have done with regard to Schoenberg’s music. It is what it is, and the concept of art being distanced, emotionally neutral and even alienating was one that was gaining ascendancy at the time.

I think that distancing effect, that difficulty we often have with Schoenberg’s music, has a lot to do with the density of his works, especially in their contrapuntal elements. There is simply so much going on at the same time that it can be hard to grasp the through-line. But the Variations in their stringency combined with their constantly evolving orchestral textures, offer one way in to this fascinating but still elusive musical world.

And Karajan and the Berliners could not be a better guide.

Music

Sound

With Pelleas und Melisande we return to the late Romantic idiom of Schoenberg’s youth. Unaware that Debussy had already completed his opera on Maeterlinck’s symbolist play (although it was not performed until 1902), Schoenberg was alerted to the material by Richard Strauss who thought it would be a good fit. Schoenberg even considered turning it into an opera himself, and later wrote:

“I still regret that I did not carry out my initial intention. It would have differed from Debussy’s opera. I might have missed the wonderful perfume of the poem; but I might have made my characters more singing.

“On the other hand, the symphonic poem helped me, in that it taught me to express moods and characters in precisely formulated units, a technique that my opera would perhaps not have promoted so well.

“Thus my fate evidently guided me with great foresight.”

Maeterlinck used his tale of doomed lovers (more overtones of Tristan und Isolde) to explore the darker, repressed passions lurking in the human heart, and Schoenberg - in contrast to Debussy in his opera, and other musical settings by Sibelius and Fauré - concentrated less on a sense of mystery, longing and poignancy, more on the eruption of those dark, destructive forces.

In keeping with that palette, the work reads almost as a shadow counterpart to Richard Strauss’s exuberant tone poems, a kind of musical version of the Upside Down from the Netflix show Stranger Things. Yes, there are conventional themes, leitmotifs in the Wagnerian manner associated with particular characters and ideas that carry the story along, but they are not exactly hummable. As so often with Schoenberg there is a paradoxical sense of both compression and expansion, especially characteristic of his pre-serial works. Thus, this tale of doomed love comes over with an edginess, an intensity and sense of straining at the bounds of current musical forms that points to the future, rather than the tone poems of Richard Strauss which, for all their experimentalism, always feel like they are offering a capstone, a celebratory validation of all that has gone before.

There is a similar quality in Schoenberg’s early, massive Gurrelieder. Like Pelleas, even as it comes across on one level as the ultimate flowering of late-Romanticism, there is also something disruptive churning away at its core, waiting to break loose from the shackles of tonality.

Needless to say, the premiere of the work in 1903 in Vienna, with the composer himself making his debut as a conductor, was a contentious affair, the reactionary Viennese again proving their reluctance to be open to new musical thinking. Wrote Schoenberg:

"The first performance... under my own direction, provoked a riot among the audience and even among the critics. Reviews were unusually harsh and one of the critics suggested that I be put into an asylum, with music paper kept out of my reach.”

Critic Ludwig Karpath went further in his condemnation:

"Schönberg's Pelleas und Melisande is not just filled with discords, in the sense that “Don Quixote” by Strauss is, but constitutes in itself a discord lasting fifty minutes. This is to be taken literally. What else might be concealed behind this cacophony is difficult to guess.”

Another huge orchestra is brought into play here, and again the Original Source opens up the original pressing’s occasionally congested and dynamically restricted palette to powerful effect. Rainer Maillard has truly conquered the acoustical challenges of the Philharmonie (where most of the sessions for this set took place) by blending in his two surround channels with the echo chamber provided by the staircase at Emil Berliner Studios to create an incredibly natural sounding, deep and wide soundstage, within which every orchestral detail emerges effortlessly. While some of the earlier 4-track releases in the Original Source series originally recorded in the Jesus-Christus Kirche betrayed some of the inconsistencies in the miking and balancing of the original sessions, these 8-track sessions in the Philharmonie sound completely of a whole, balancing detail with a sense of the orchestra in all its glory massed in front of you.

(Likewise, for the two 4-track recordings made in the Jesus-Christus Kirche - Berg's Three Orchestral Pieces, Webern's Six Pieces for Orchestra - there is a far greater coherence to the sound picture and integration with the hall acoustic than in some of the earliest Original Source reissues).

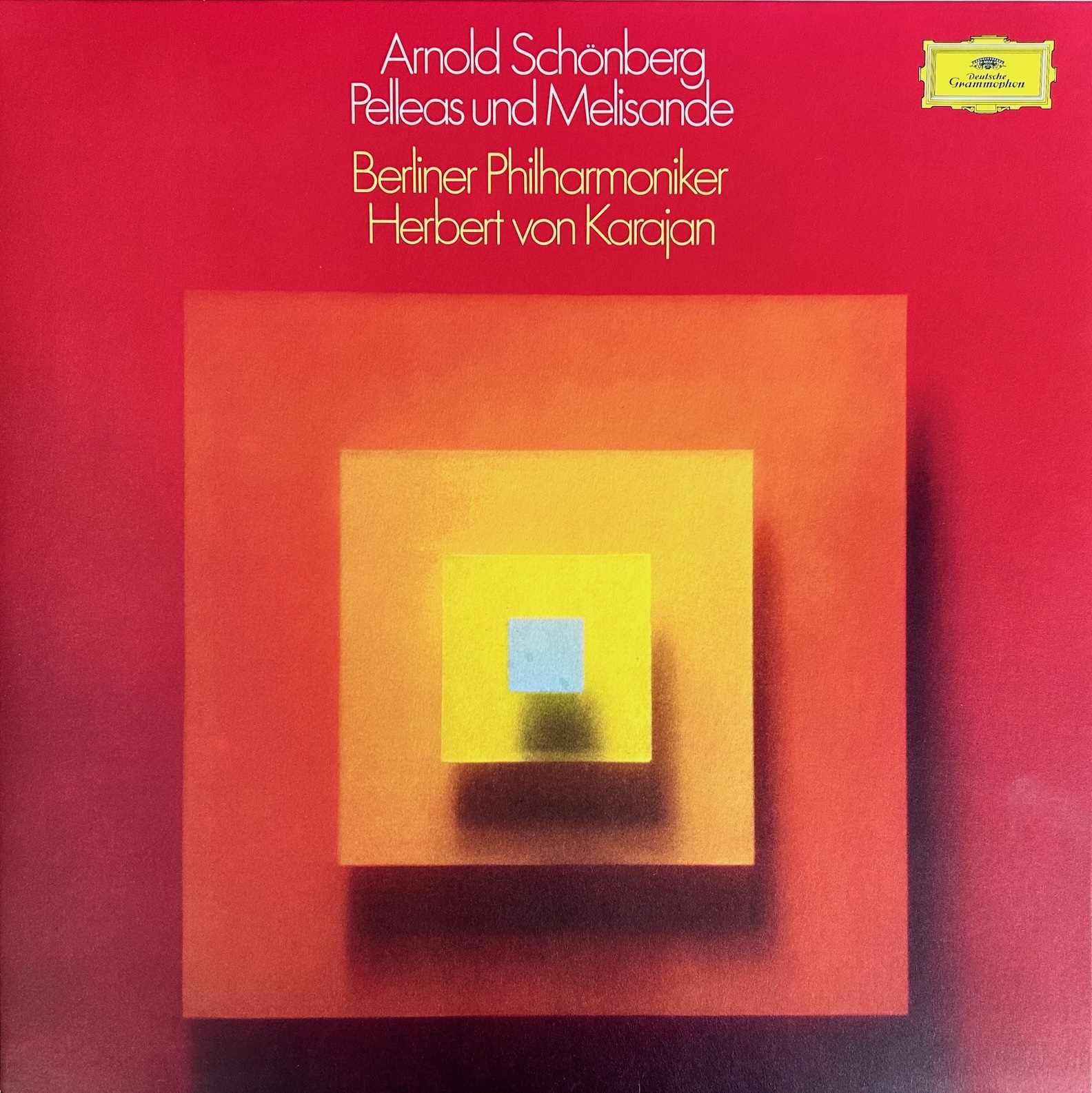

Original Source Gatefold

Original Source Gatefold

Needless to say, Karajan’s way with this score is something to behold, as he brings to bear all his formidable powers as a Strauss interpreter of the first rank. He and his virtuoso players bring out every telling nuance of this complex score with a vengeance, rumbling in the subterranean seething of repressed passions, surging into hormonal climaxes, relishing all the pointillistic detail that ebbs and flows. Schoenberg’s powers as an orchestrator are again on full display, here in the service of full-on Romantic expression. Again and again you will marvel at the brilliance of the Berliners in this music - is there any other orchestra that has ever played quite like this?

For me the work proceeds like some barely contained stream of consciousness in which every moment of shifting emotion is marked and expressed, the seething subconscious always threatening to emerge unfettered - and sometimes it does just that. Scenes of eerie foreboding give way to huge rolling waves of brass, with strings surging and receding through the glare. At a certain point I found myself also thinking of the film scores of Erich Wolfgang Korngold and Max Steiner. Both of them - like Schoenberg - were products of the Austrian music scene, and they essentially invented the style of classic Hollywood film scoring, using similar techniques (including leitmotifs) to the ones employed in Pelleas. (Once he moved to Los Angeles, Schoenberg tried to get film work, but it was not to be).

The distinctive silky tones of principal oboist Lothar Koch and principal flutist James Galway, leading the immaculate wind section of the Berliners during this period, acts as a binding force between the strings and brass. The massive climaxes of Schoenberg’s huge orchestra playing at full tilt, when they come, come in waves, like a tsunami hitting land - completely different to the more processional and terraced climaxes in Bruckner.

The remastered sound is awe-inspiring in these moments, fully accommodating not only the giant mass of the huge orchestra but all the detail within. The way in which Karajan and the Berliners generate, catch and ride these tsunami waves of sound has to be heard to be believed. I’m really not sure I’ve ever heard anything quite like it.

Again, this is a work I feel I am still coming to grips with, even more than 50 years on from when I first heard it in this recording, but with each listen I am drawn further into the unique musical and sound world Schoenberg has created. And this remastering will hold you in the same thrall it held me in my last couple of listens.

Music

Sound

“The time was simply ripe for the disappearance of tonality. Naturally this was a fierce struggle; inhibitions of the most frightful kind had to be overcome, the panic fear, 'Is that possible, then?' So it came about that gradually a piece was written, firmly and consciously, that wasn't in a definite key any more.”

Composer and Conductor Pierre Boulez

This record of two of Berg’s inarguable masterpieces was my most played from this set since the day I bought it when I was 14. This was my introduction to Berg’s music, and after hearing it I eagerly sought out his other works, especially his opera Wozzeck, which I soon managed to see at the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden with my ‘cello teacher playing in the orchestra. Some years later, in 1981, I saw the newly completed opera Lulu, in a stunning production by Götz Friedrich, conducted brilliantly by Colin Davis. These are two of the supreme masterpieces of 20th century modernism.

Berg left us far fewer works than his teacher, but they are all distinctive, and include the haunting Violin Concerto (my personal favorite violin concerto). The composer died young of sepsis from an insect bite.

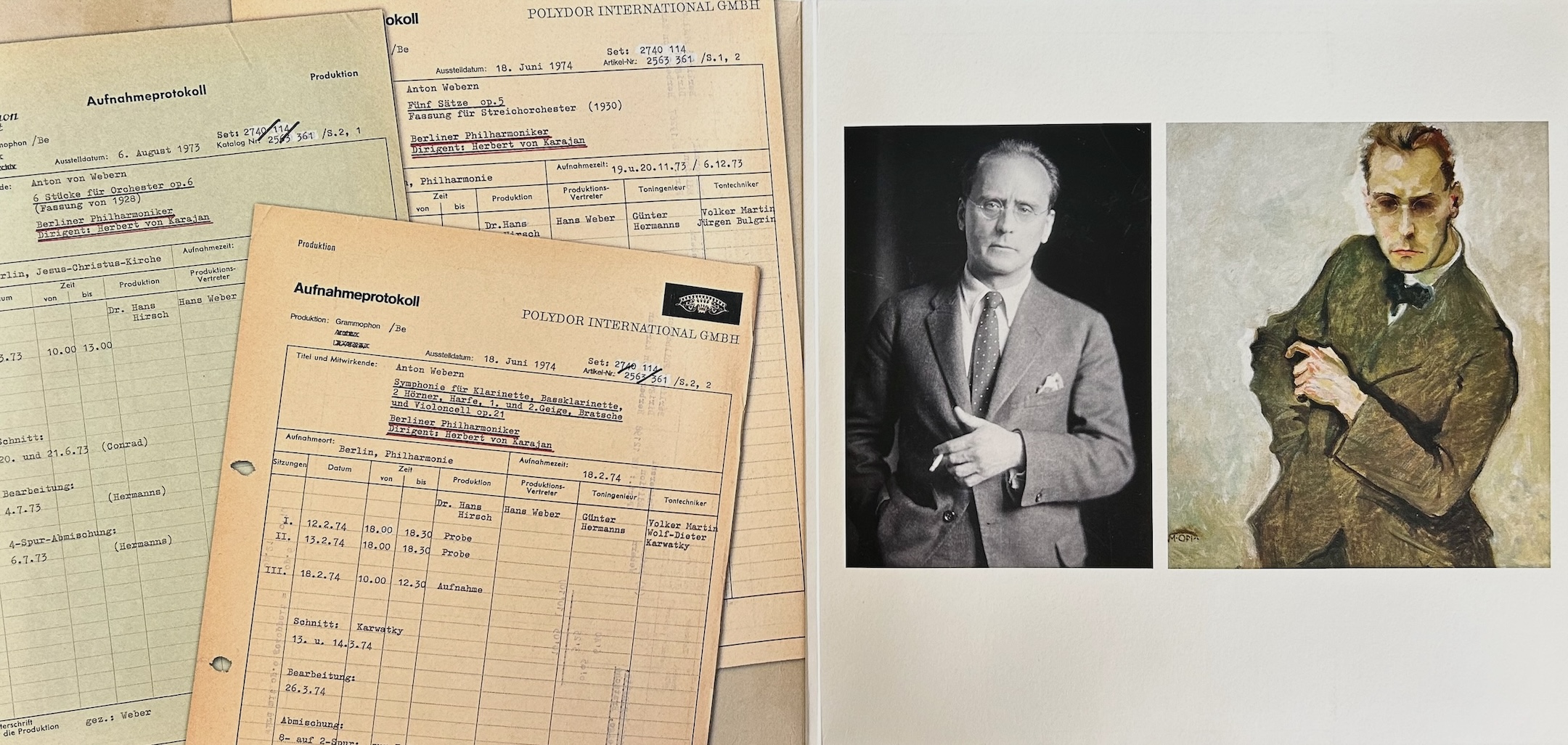

Portrait of Alban Berg by Schoenberg (1910)

Portrait of Alban Berg by Schoenberg (1910)

For many, Berg remains the most approachable of the triumvirate of Second Viennese School composers, and the two works on this record, which could not be more different in temperament and sound, demonstrate why.

Berg managed to channel his atonal and serialist techniques in a more overtly emotional and approachable manner than his teacher, and his fellow pupil, Webern, even to the extent of sometimes conveying a sense of (almost) traditional melody and harmony that the listener can latch onto. He even “lapses” into tonality on occasion! He particularly focused in on one of Schoenberg’s favored compositional methods, that of “developing variation”. In his essay titled “Bach, 1950”, Schoenberg wrote:

This [developing variation] means that variation of the features of a basic unit [of thematic/harmonic material] produces all the thematic formulations which provide for fluency, contrasts, variety, logic and unity, on the one hand, and character, mood, expression, and every needed differentiation, on the other hand—thus elaborating the idea of the piece.

Schoenberg considered Brahms one of the primary masters of this method.

I think Berg’s use of this technique is one of the reasons his music is more approachable; because instead of endless, interweaving, dense contrapuntal writing (as in his teacher’s works), Berg’s method keeps bringing us back to the originating musical material. There is something for the ear to latch onto. The variation principle is one of the driving forces in the score for Wozzeck.

Berg is more interested in communicating emotion than fulfilling theoretical dictates. A good example of how he can startle with conventionality comes in one of the orchestral interludes in the final act of Wozzeck, where Berg mirrors the escalating horror of the psychodrama unfolding onstage with the simplest of means. In a jealous rage the hapless soldier Wozzeck has just murdered his wife. He flees the scene. In the following orchestral interlude there’s no atonal complexity, just a unison note in the orchestra that starts from an almost inaudible nothing and builds twice to a pulverizing climax. It's as if the music is terrorizing him, driving his psychotic break ever onward - but using just a simple, crescendoing unison note and relentless drum assault.

Those drum blows return in a similarly harrowing manner in the last of the Three Orchestral Pieces, Op. 6, which make up side one of Karajan’s Berg record.

I have no hesitation is saying that this is one of the defining works of early 20th century classical music, up there with Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring, Mahler’s 6th Symphony, Bartok’s Music for Strings, Percussion and Celeste, Sibelius’s 4th Symphony, and Varése’s Amériques. It is one of those works that - if I see a recording of it I am unfamiliar with - I’ll buy it, curious as to whether it will surpass Karajan’s rendering. None have.

It’s one of those chameleon kinds of works, one that can sound like a completely different piece depending on who is performing it. It is a profoundly complex, layered score, with all kinds of shifting instrumental and dynamic interplay that is really hard to integrate into a forward musical narrative. The one time I heard it done live, with Bernard Haitink conducting the Vienna Philharmonic no less, I felt like I was hearing all the detail and letter of the score, that it was a completely “accurate” representation, yet communicated none of its musical intent.

One of the raps against the Karajan version over the years was that he fudged the detail and accuracy in favor of his “interpretation”. As Richard Osborne writes in his biography of the conductor:

Questions have most often been asked about Karajan’s shaping of the work he himself found so emotionally shattering: the terrifyingly prophetic, war-racked Three Orchestral Pieces completed by Alban Berg in 1914-15. For some, Karajan’s reading is more a free paraphrase of the music than a realization of what Berg actually wrote, phrases elided, inner detail selectively used. That the reading was always a fiercely emotional one - more Furtwängler than Boulez - there is no doubt, Karajan consciously trading vision for accuracy.

Berg wrote the Three Orchestral Pieces (originally intended as a large one-movement symphony) on the rebound from some negative feedback from Schoenberg on the Altenberger Lieder and the Four Pieces for Solo Clarinet.

Berg sent the last of the three orchestral pieces to be completed, the second, to his teacher as a 40th birthday present in 1914, and wrote in his accompanying letter:

“My hope to write something more independent and yet as good as these first compositions, something I could dedicate to you without incurring your displeasure, has been repeatedly disappointed for several years… I cannot tell today whether I have succeeded or failed. Should the latter be the case, then in your fatherly benevolence, Mr. Schoenberg, you must take the good will for the deed.”

Berg had had a somewhat wayward youth, even impregnating a household servant at the age of 17, and did not turn to music until comparatively late. He was largely self-taught until he became Schoenberg’s pupil when he was 19. By all accounts the stern yet sensitive guidance of the older man was just what he needed to guide his compositional journey, having lost his own father at the age of 15.

The first of the three pieces, Praeludium, opens in a haze of tam-tam and other percussion which give way to vague, disjointed orchestral murmurings (including what sounds like a baleful echo of the opening bassoon solo from The Rite of Spring, premiered a year earlier) which grab your attention immediately in this remastering. As crushing brass give way to lamenting strings and sighing wind, the overall mood is of overwhelming melancholy fighting despair. I always have an image of hands and arms trying to claw their way out of the mud of a battlefield (as at the end of the battle scene in Orson Welles’s Chimes at Midnight). A huge climax which feels like the death of hope subsides into the murk of the piece’s opening. This is music of struggle and despair, of savage beauty and heartbreak.

You can read the second piece, Reigen (Round Dance) as Berg’s unhinged riposte to a Mahlerian Ländler, all expressionistic angst shot through with moments of delicacy and beauty (conveyed with brilliant strokes of unconventional juxtapositions of orchestral sonorities, especially percussion). Imagine a landscape by Constable reimagined by Francis Bacon. The dénouement is an orchestral coup de théâtre, with oscillating, high trilling woodwinds in an atonal chord-spread, set against growling brass and defeated strings. These and similar effects are put to more overtly dramatic effect by Berg in his subsequent opera Wozzeck; they are no less startling here.

The final coruscating March is truly a March into Hell, reflecting the outbreak of senseless institutionalized carnage that would drown Europe in mud and blood. Berg’s combination of expressionist angst with his mastery of the orchestra, let alone his application of new atonal techniques that still somehow manage to connect with an older sense of tonality, creates a landscape than conveys all the doom and terror of World War I. The music goes even further, hinting at all the cataclysms to come during the 20th century, not least the dawn of the all-annihilating atomic and hydrogen bombs in its final apocalyptic nihilism.

Claggett Wilson, "Flower of Death - The Bursting of a Heavy Shell - Not as It Looks, but as It Feels and Sounds and Smells", c. 1919

Claggett Wilson, "Flower of Death - The Bursting of a Heavy Shell - Not as It Looks, but as It Feels and Sounds and Smells", c. 1919

It is impossible to convey the sheer inexorable, brutal power and force of Karajan and the Berliners here, which culminates in a series of thunderclaps - drum and brass driven climaxes that seem to level creation. Just listen - and quake in your boots.

And then, out of nowhere, a weird, chugging processional hints at possible relief and respite with half-forgotten disappearing melodic fragments, plucking harps, a chirping clarinet and piccolo…a ghostly solo violin phrase joined by ‘cello… Is this new shoots of life peeking out from amid the mud and ruins?

“Abandon hope, all ye who enter here!”

All is swept aside by a musical scythe of doom: fortissimo tam-tam, dissonant brass fanfares, a demented xylophone, and the final hammer blow of a bass drum.

It all reads like a mad man’s reimagining of the Finale to Mahler’s 6th Symphony - a terrifying prospect, since that piece was already about the felling of all of a man’s aspirations and dreams, once and for all.

If you’ve never heard this work before, buckle up!

One small note. This is one of the recordings in the set derived from 4-track, not 8-track, master tapes, and was recorded in the Jesus-Christus Kirche, not the Philharmonie. It lacks some of the added precision that comes with the sound engineers having the use of those extra tracks, in terms of how the original recording team and Rainer Maillard are able to fine-tune the balances within the orchestra and between the orchestra and the hall's acoustical space. But that’s really just me quibbling, wishing for that last extra ounce of sonic magic for this blockbuster recording that, even in its original release, was a highlight of my record collection, a work I returned to often.

In its new incarnation it is magnificent - and hair raising.

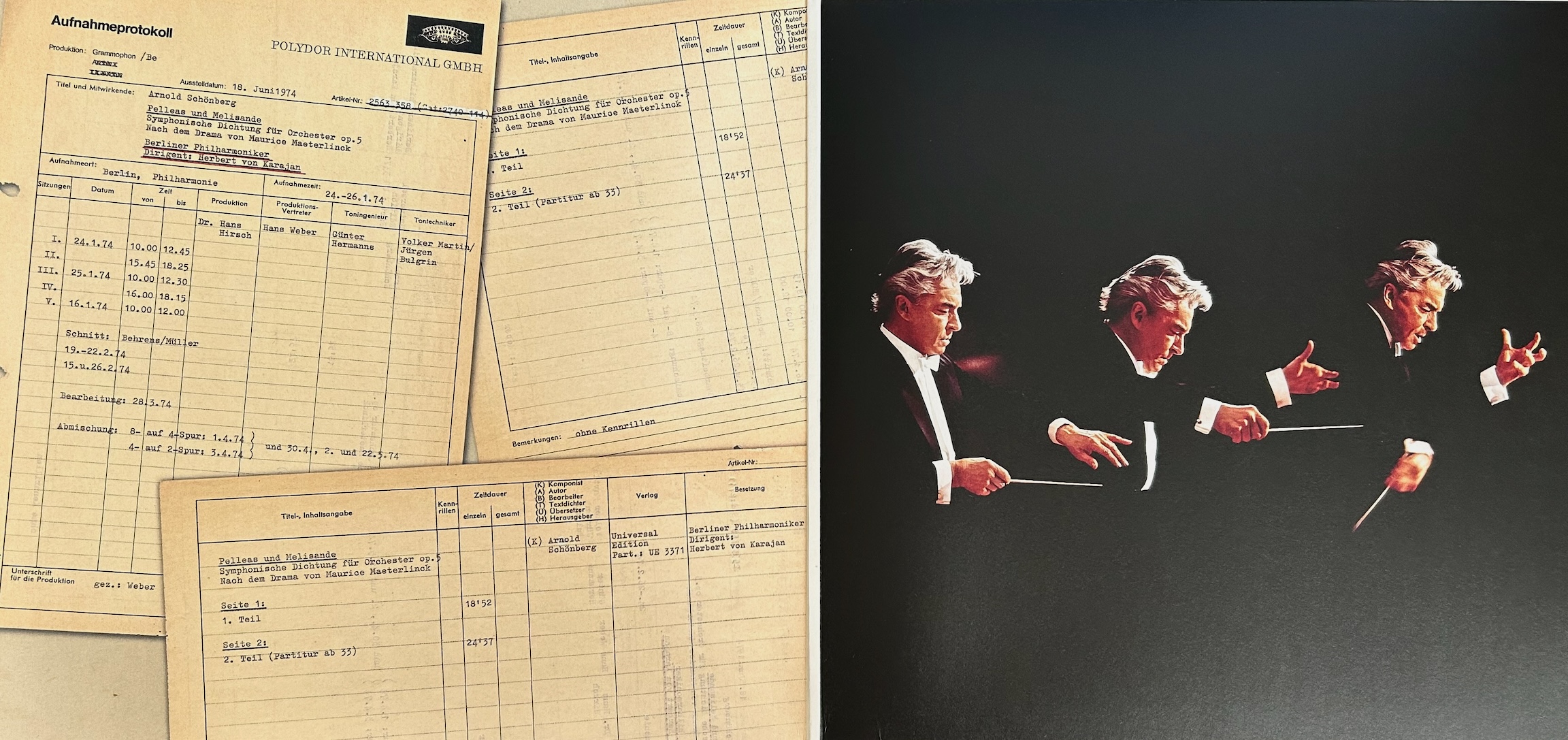

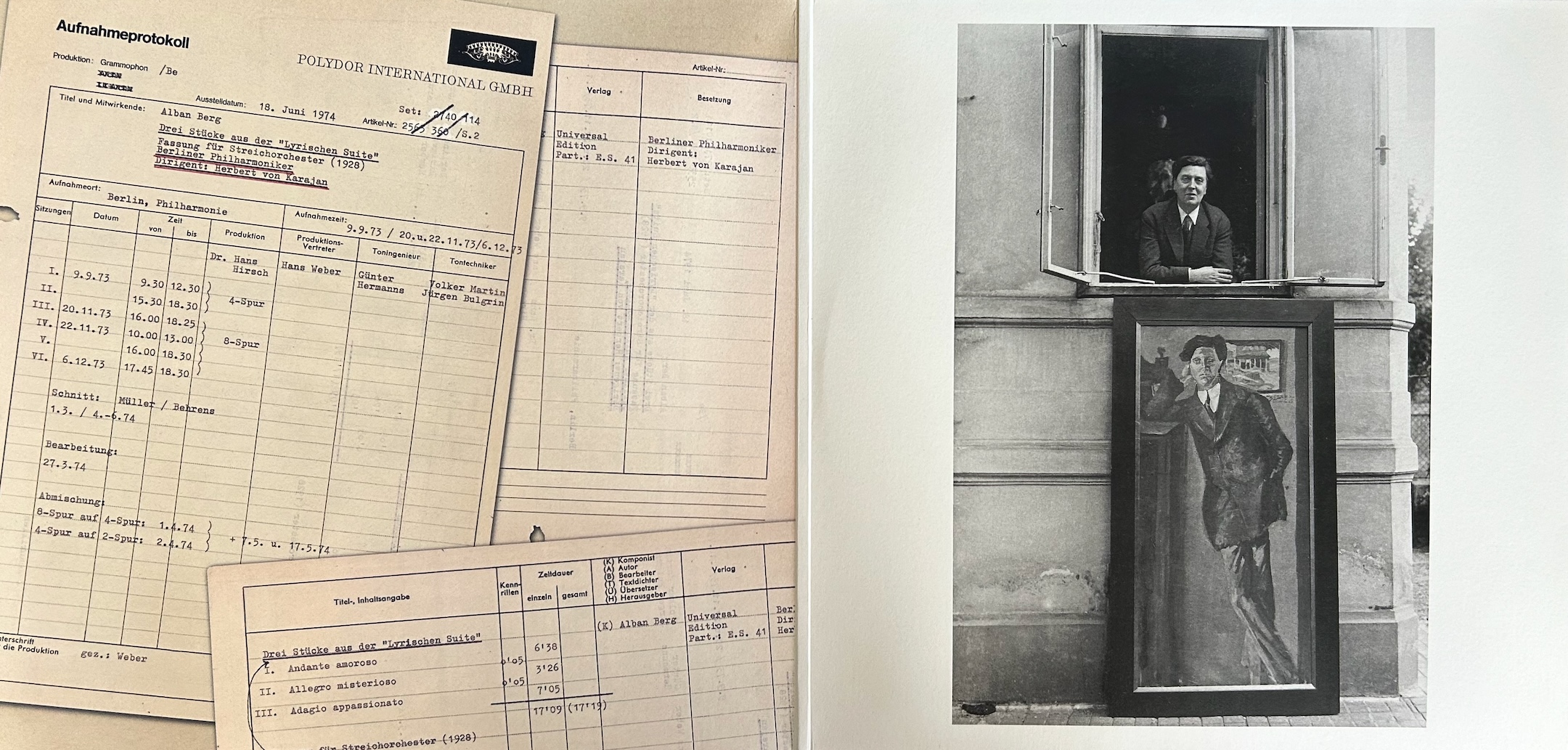

Original Source Gatefold, featuring a photo of Berg with Schoenberg's portrait of him

Original Source Gatefold, featuring a photo of Berg with Schoenberg's portrait of him

If you are wondering how to follow that, merely flip the record and you will be greeted by music of an entirely different hue: ravishingly romantic in sound and form. This is all the more surprising given that the work is fully atonal, using 12-tone techniques. If you think the string sound on Schoenberg’s Verklärte Nacht is off-the-charts gorgeous, wait until you spin this.

My jaw dropped as this thing got going. It defies description in its gorgeosity. There’s even more golden burnished string tone, rippling and rumbling string bass (be still my heart) and dynamics that take you for a ride on the world’s most extreme roller-coaster.

What more can I say? With my all-tube set-up I had expired and gone to heaven. And whatever your system, this is going to send you there too. It’s probably the most sonically intoxicating side in the whole set.

The orchestral Lyric Suite is actually just three central movements extracted from the original six movement work for string quartet, arranged by Berg for full string orchestra.

The original Lyric Suite for string quartet is in fact a musical cypher for a secret, passionate love affair between the composer and Hanna Fuchs-Robettin. He had stayed with her and her husband Herbert on a visit to Prague to hear Alexander von Zemlinsky (Schoenberg’s teacher and brother-in-law) conduct extracts from his opera Wozzeck in 1925. The affair began immediately, and the Lyric Suite is full of coded references to the lovers, from their names broken down into notes and melodies, and even tempo markings and numbers of measures/bars relating to the number of letters in their names.

From an LAPhil program note (author unknown):

This was not known, however, until 1977, when American composer George Perle visited Dorothea Robettin, the daughter of Herbert and Hanna, and saw the copy of the score that Berg had annotated for her mother. It had been clear from the first that some sort of extra-musical program lay behind the “Lyric Suite, which Berg’s pupil Theodor Adorno called a “latent opera.” The copiously annotated score, however, makes this narrative explicit. (The adjectives applied to each movement are a strong hint to the narrative arc, as are the tempos – the fast movements get faster and the slow movements slower in an expanding wedge, as delirium leads to the despair of parting.)

The middle three movements that make up the orchestral version are the most overtly romantic, and this rapidly became one of Berg’s most popular scores.

The opening Andante amoroso will immediately put you in mind of Bernard Herrmann’s muted strings-only score for Psycho (1960), with its disjointed violin lines and sense of alienation combined with romantic yearning. Undoubtedly Herrmann would have had Berg’s music in his mind as he set to work. As always, Berg manages to connect his atonal and serial procedures with the listener on a more visceral level than his teacher.

The agitated pizzicati and tremulandi of the Allegro misterioso convey a sense of the lovers’ heart palpitations, agitation, excitement - and fear of discovery. It’s a heady mix, conveyed with all of the BPO strings’ customary virtuosity. The players toss off this incredibly challenging music with the same alacrity with which they might play Vivaldi’s Four Seasons. As the music fragments and reassembles one can discern the seeds of how future avant-gardists like Penderecki and Ligeti will approach string writing.

The final Adagio appassionato is where Berg gives all his inner turmoil and romantic yearning full rein. If this is how true love feels, would you really want it? Again, the expressionist idiom is so much more visceral than in Schoenberg or Webern’s works. It is often quite overpowering, especially in Karajan and the Berliners virtuosic hands and bows. The work seems to end in despair at the knowledge of imminent parting. There descends a relative calm, where a lonely solo violin is set against the other collective players’ forlorn, fragmentary phrases and vast empty chords stretched across a now barren harmonic landscape.

All is lost, all is grey and colorless. The end of love. The end of life.

Thus concludes an album of music which shows Karajan at his interpretative best, a true highlight of his entire career on record.

Music

Sound

But wait. There’s more…!

“Your ears will always lead you right, but you must know why.”

“If you want to make something clear to someone, you mustn't forget the main point, the most important thing, and if you bring in something else as an illustration you mustn't wander off into endless irrelevancies.”

Anton Webern

“Webern was a kind of 'Kamchatka of music,' an unknown country of music. That's true; for me and people of my generation, he was a radical - you couldn't be more radical than he was.”

Pierre Boulez

Revisiting this album of music by the member of the Second Viennese School whose music is perhaps the least well-known, but is in many ways the most influential, was perhaps the biggest surprise of all. I was completely taken aback by how much I fell in love with this record - its music and its riveting sound.

“Riveting” is a great word to describe the experience of listening to this record. The combination of Webern’s minimalistic approach, in which literally every note, every dynamic, every chord is a universe unto itself, with sound that both pulls you into all that compressed musical energy and charged detail, yet also expands the music outwards into a huge soundstage that envelops you - well, it’s heady stuff!

From the first unison string plucked notes of the Passacaglia (1908) I was leaning forward into Webern’s unique sound world in a manner I have never done before. Rarely have I heard anything of this simplicity contain this degree of concentration, of barely contained energy. A panther’s slow footfall as it stalks its prey, ready to erupt into a frenzy of focused, directed power at any moment.

I’m going to linger on this point here for a moment. I cannot think of any few seconds of any record which presents a better argument for the virtues of all-analogue recording, mastering, cutting and playback. The music is simplicity itself. But all the focus, energy, concentration that happened in that moment in the Philharmonie when conductor and players began to play is there in the grooves. It is there rather than represented - the thing itself. You can hear how the players’ fingers grasp the strings, how the strings resonate on the fingerboard and continue on into the wooden bellies of the instruments. You can hear how those plucked notes re-emerge and then resonate in the hall. It was all caught on tape, something beyond the mere notes and their sound, and you not only hear it all - you feel it. There is no sense of this being a facsimile of the sound, as can happen with digital. No - you are right there.

And it is electrifying.

The musical form of the passacaglia dates back to the 17th century, and is in essence a series of variations on a repeated phrase - thus a kissing cousin to Schoenberg’s notion of “developing variation” that so inspired Alban Berg.

Webern gave this work the designation of being his official Opus 1, for he felt it was the first work that fully expressed his true musical personality. (One of the most ingratiating of his earlier works is a fully-fledged symphonic poem, Im Sommerwind, which I urge you to seek out in comparison - you’d hardly believe it’s by the same composer; the recording by Boulez in his DG complete works set is excellent, and was engineered by the same Rainer Maillard behind the Original Source Series).

Even though the Passacaglia is written in an idiom that still has one foot in the door of more conventional late 19th-century writing, it clearly announces a new sensibility, and everywhere you will hear pre-echoes of Webern’s mature, distilled style.

Karajan and the Berliners’ performance is simply breathtaking, keeping its grip inexorably on the music (and you) at every unpredictable turn. I have heard no other recording to match both its concentration and expressive fluidity and, somehow, its simultaneous opulence and stringency. The Original Source refresh gives the music infinitely more dynamic headroom and timbral resonance than the original. This has rapidly become a new favorite in this set.

A taste of thing to come - which arrive with a vengeance in the opening bars of the first of the Five Pieces (Movements) for String Orchestra Op. 5 (1909/1930) - all atonal bite and frenzy. This is the Bernard Herrmann Psycho sound on steroids. It’s a thrilling juxtaposition with the Passacaglia.

This is the orchestral version (made in 1929/30 by the composer) of his 1909 string quartet original. It completes the triptych of strings-only works (along with Schoenberg’s Verklärte Nacht and Berg’s Lyric Suite) which pepper this set, and allow you to hear the full range of possible writing for the string section of an orchestra, with the BPO players proving they are in a league of their own in this regard. I must confess to being something of a “stringaholic” in my record collecting habits, with a tendency to grab any record of this kind of repertoire. Several of my favorite records are devoted to strings alone (for example, Britten’s English Music for Strings on Decca being one, Barbirolli’s classic album of Vaughan-Williams’ Fantasia on a Theme of Thomas Tallis on EMI being another).

With the Five Pieces we fully enter the Webern experience. This may seem outwardly disjointed, cold, clinical in other performances and recordings, but Karajan and his players attack this like it was Beethoven’s 5th, and there is so much emotion that they bring to the table. In the second of the five pieces, for example, when the music gives way to isolated solo lines in the first desks, juxtaposed with tutti interjections, there is almost a sense of wailing souls lost in the ether, trying to find a way home. Webern’s atonal lines almost begin to sound like tunes!

The third piece is a 43 second motoric moto perpetuo, like a brief, inexorable ride into Hell.

The empty vistas of the fourth piece barely contain disjointed utterings, voices in search of words to express what they are trying to say. The sense of dislocation and being lost is overwhelming, but a final solo violin line hints at finding safe harbor - but finally the music simply evaporates.

Yet as we move into the fifth piece certain moments encompassing a surging line, or quiet chord, hint at the possibility of resolution, even redemption.

This work is really like stepping into the cellar of Norman Bates’s mother’s house in Psycho, walking past her mummified remains in the rocking chair, and finding a hitherto secret trap door, opening it, and walking down the steps into a secret vale of unknown mysteries - and possible horrors.

Let me just mention here the original engineering of Karajan’s go-to team of producer Hans Weber and Günter Hermanns, responsible for this entire set. The string sound is technicolor three-dimensional: woody, rich and sharp in equal measure, resonating beautifully with the Philharmonie. The superb remastering and cutting of the Emil Berliner Studios team of Rainer Maillard and Sidney C. Meyer removes any trace of the glassiness that often afflicted the string sound on DG’s original vinyl releases of this period.

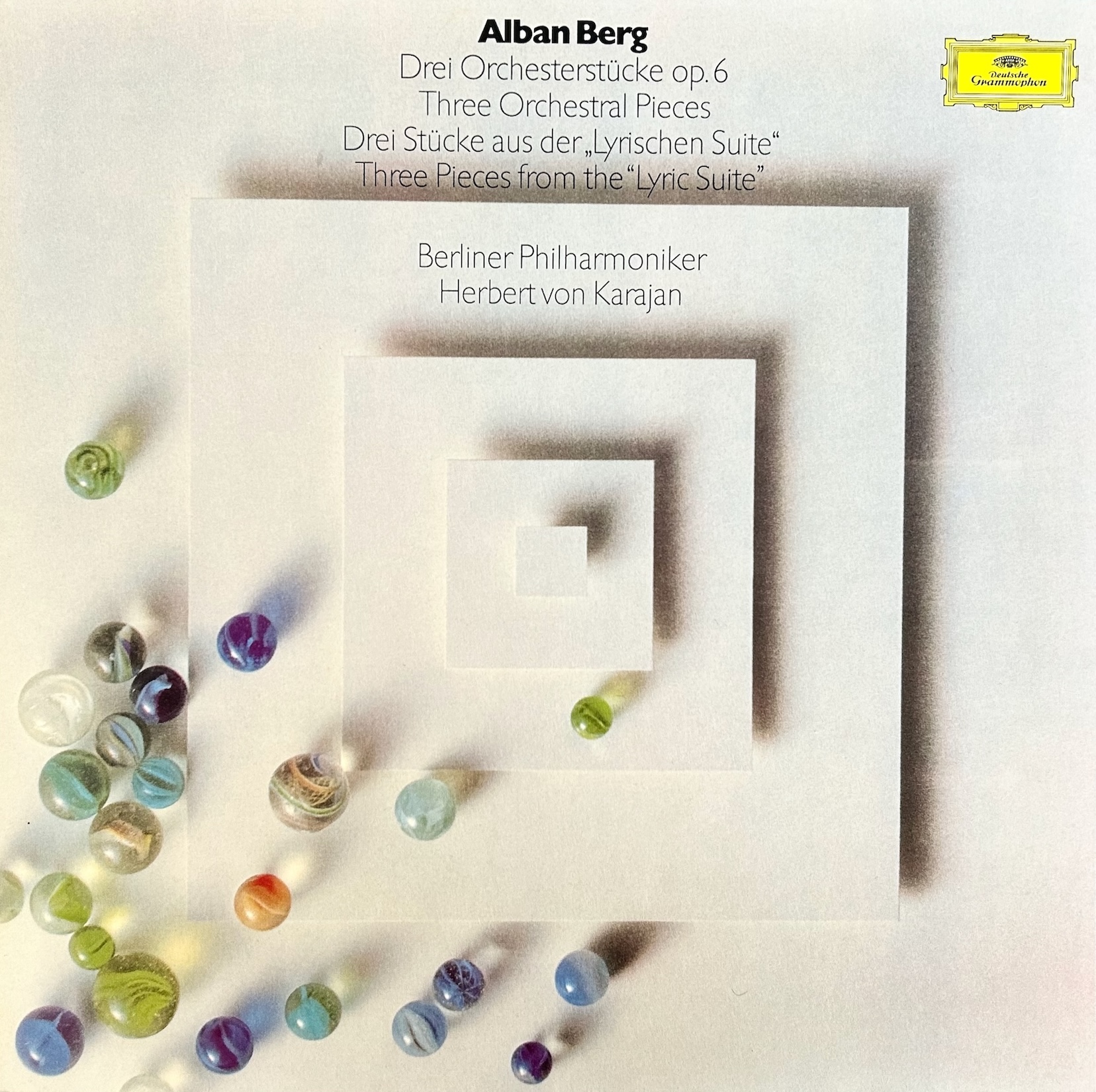

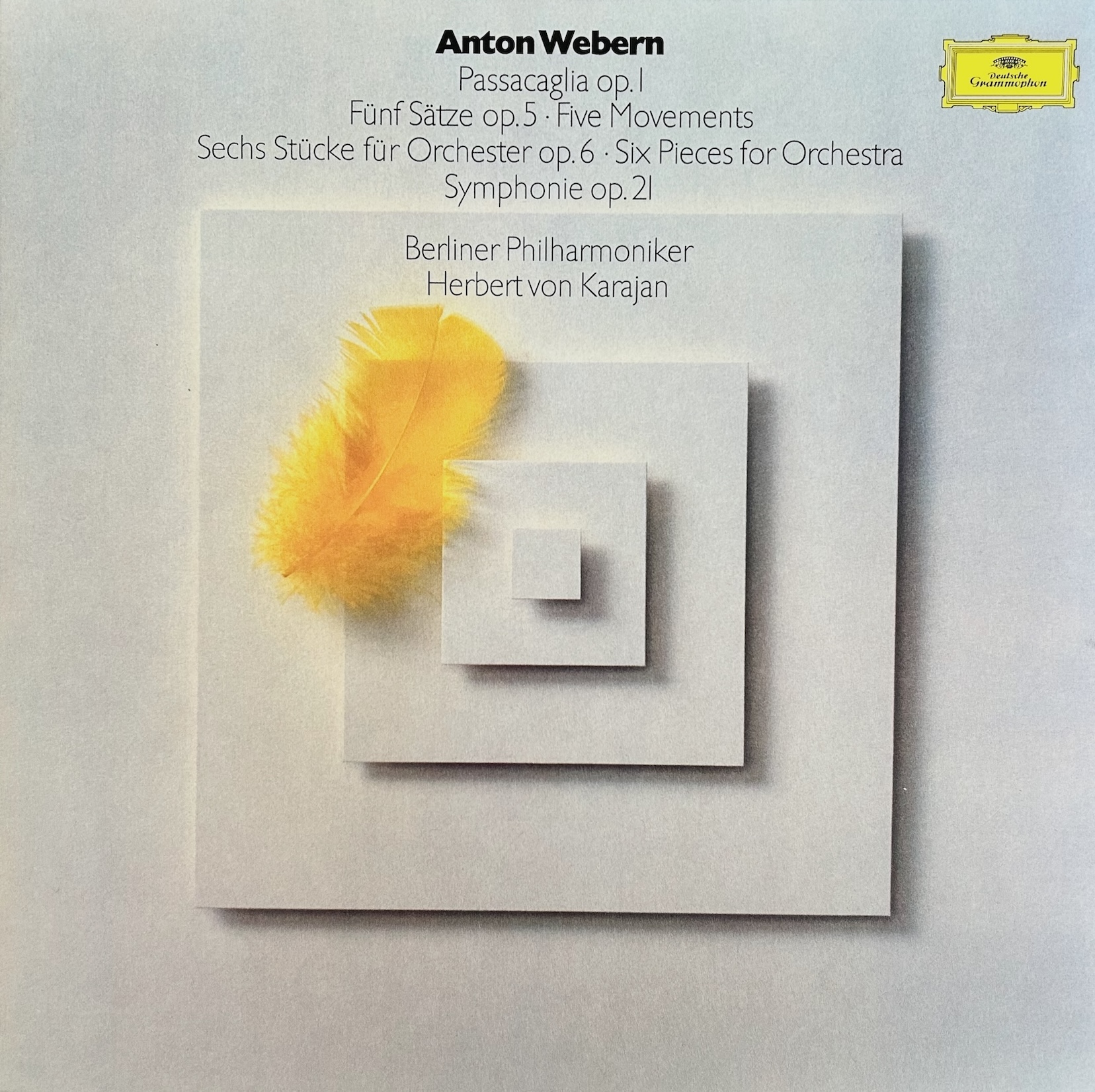

Original Source Gatefold, featuring recording notes and a photo of Webern next to Max Liebermann's portrait of him

Original Source Gatefold, featuring recording notes and a photo of Webern next to Max Liebermann's portrait of him

The centerpiece of this Webern selection is the Six Pieces for Orchestra Op. 6, in its later 1928 revision which simplifies some of the orchestration. (If you want to hear the earlier version, check out Boulez’s version in his DG remake). Webern rarely worked with large orchestras, but here he fully explores the diverse capabilities of his expanded canvas. He dedicated this work to his teacher Schoenberg, who conducted the first performance in front of an unhappy, rowdy crowd of laughing Viennese in 1913.

The character of each piece is given away in its title, with the Funeral March of the fourth piece being by far the longest at just over four minutes. Brevity is the name of Webern’s game, with him injecting each note, each chord, each different instrumental timbre with compressed meaning and possibility. You never know from one moment to the next where the music is heading. You really do have to listen to Webern’s music differently - in the moment - but once you do it is a very invigorating, almost purging experience. Sounds you are used to hearing in a more traditional context - like harps or tubas - are removed from that context and register in new ways. Dynamics, and dynamic contrasts, can exist in their own right, completely divorced from their usual role as part of an ongoing musical phrase or argument. Piece 2 will startle you with its distorted eruptions. Piece 3 sounds like it might be a throwaway, until you realize it’s the calm before the storm of Piece 4, the Funeral March. (In a letter to Alban Berg, Webern once wrote that: “Except for the violin pieces and a few of my orchestra pieces, all of my works from the Passacaglia on relate to the death of my mother.”)

The Funeral March is the only piece that proceeds with something of a steady rhythmic beat underpinning it, although this is deconstructed in the halting second section, with disembodied brass grunts keeping the forward momentum going. Then we get into the long crescendo that leads into a pulverizing climax (look to your speakers on first audition). Tubular bells, drums, gongs and tam-tams gradually overwhelm all else. Would you be surprised to learn I once used this music to accompany a film sequence which culminated in a nuclear detonation? Nope. Tailor made, I’d say.

Piece 5 feels like a vision of nuclear winter, again with Webern exploiting radical orchestral juxtapositions.

Piece 6 returns to an Earth we might recognize, with moments that feel like gestures towards traditional harmony - without actually being same. A disjointed solo violin plays against disembodied brass, over an undulating bed of sustained quiet but predatory tam-tam rumblings. Finally the resonating percussion is all you hear, punctuated only by perfunctory, then evaporating celeste.

Along with the Berg Three Orchestral Pieces, the Webern Six Pieces for Orchestra Op. 6 was recorded to 4-track, not 8-track, with sessions taking place in the Jesus-Christus Kirche rather than the Philharmonie. The switch from 4 to 8-track when mastering side two of the LP required Rainer and Sidney to go through a well-rehearsed dance of unplugging and re-attaching cables, flipping switches etc.

The final Symphony for Clarinet, Bass Clarinet, Two Horns, and String Quartet is actually in only two movements, and has little in common with its First Viennese School ancestors; yet it nevertheless feels like a return to a semblance of musical normality after what has gone before.

Webern’s now full embrace of his teacher’s 12-tone method allowed the composer to inject a new level of order into the formal structure of his pieces. The Symphony is constructed from elaborate designs (like the motivating tone row being built from two halves that mirror each other). The first movement is a double canon, the second a series of variations (incorporating more canons). In harkening back to these forms from olden times (the passacaglia and canon), Webern betrays his admiration for the great composers of the Renaissance and Baroque who composed within firm strictures of contrapuntal rules and regulation. (Seek out his beautiful orchestration of the Ricercata from Bach’s A Musical Offering). He did, after all, edit the second volume of Heinrich Isaac’s Choralis Constantinus for his doctoral thesis. Writing of the first variation of the second movement, a double canon for string quartet, Webern remarked: “Greater coherence cannot be achieved. Not even the Netherlanders [ie. Isaac, Josquin des Prez etc.] have managed this.”

The Symphony brings out a different aspect of Karajan - his admiration for Bach and his ability to clarify and illuminate the structural underpinnings of the Old Masters of classical music. He reapplies those abilities to Webern’s complete reinvention and re-imagining of the building blocks of music. What could sound like disconnected notes and phrases proceed with a sense of underlying purpose and order - even if you, the listener, cannot fully perceive or articulate what that order is. Unike so much later hardcore serial music, this means that on some level you are still orientated and therefore engaged with the music. What you can also do is immerse yourself in the sounds of the work, which are otherworldly, the familiar robbed of all familiarity. This remains probably the hardest work in the set (along with the Schoenberg Variations) to wrap your ears around, but give it a chance and you will begin to sense the underlying design, and enter the strange, unique but compelling world of Anton Webern.

As Pierre Boulez writes in his introduction to the Complete Webern Works box on DG:

In a century with no scarcity of remarkable figures, Webern nevertheless occupies a special place. Revolutionary? Certainly, but without any fuss and with an incredible discretion. Radical? Absolutely, but with a kind of unworldly naïveté - creating music that gradually distanced itself from immediate seductiveness to achieve the fascination of a deliberate asceticism. Purity - of language, of expression, of intention: this is perhaps the best word for summing up the character of this music, seemingly sparse yet rich in its multiple repercussions.

Music

Sound

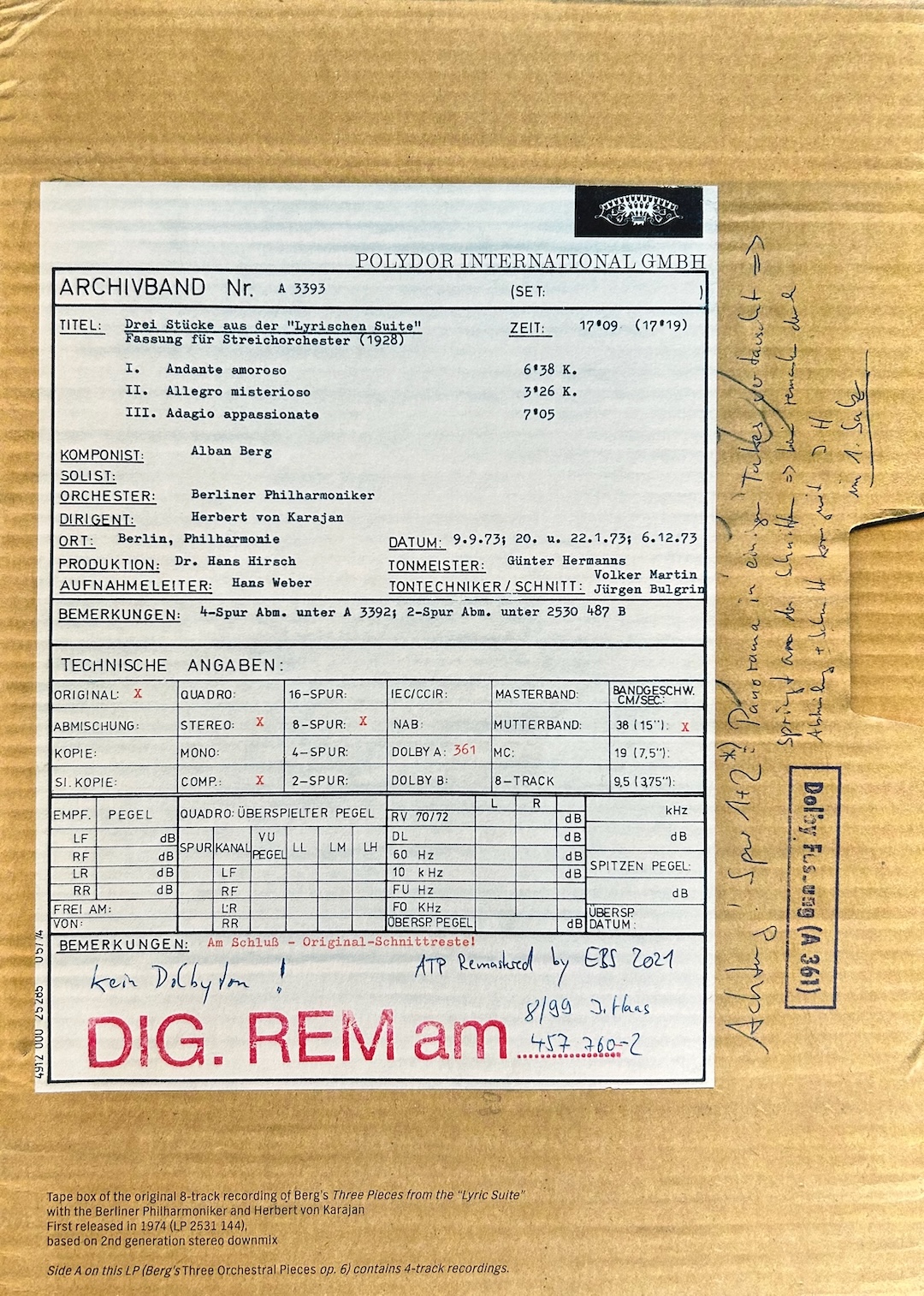

Now for a quick run-down on this set’s overall packaging etc. Unlike the original 1974 release, which was a box set containing the four records plus a booklet, here we get all four records in their later incarnation as separate releases, sliding into a sturdy slipcase. As usual, each record comes in a matte finished gatefold replicating the original design, with additional photography of the composers/performers, and of session documentation. A separate insert contains the usual essay from Rainer Maillard and Sidney C. Meyer about the technical process involved in the Original Source remastering and cutting, and a photograph of the relevant tape box. (And while we’re about it, let me just again highlight Meyer’s extraordinarily dynamic cuts for all these OSS records). Sleeve notes by a Mr. H.H. Stuckenschmidt are reprinted from the original releases: in this case they are merely sufficient for their purpose, but nowhere near the superior, elegant contributions made by musicologist Richard Osborne to later Karajan releases, including the Bruckner Symphony box.

The biggest advantage to having each individual release in its own packaging is that you get to see the stunning artwork and design created by Holger Matthies for both the original box and the separate records as they were released in the following years. Each cover image is a variation on the iconic graphic created for the original box set. (Back in the day I actually bought the single albums just so I would have their beautiful artwork for display).

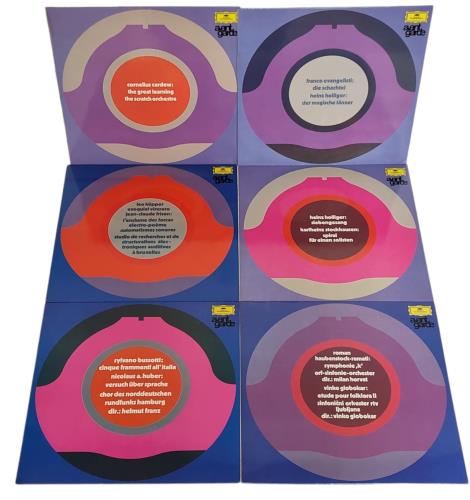

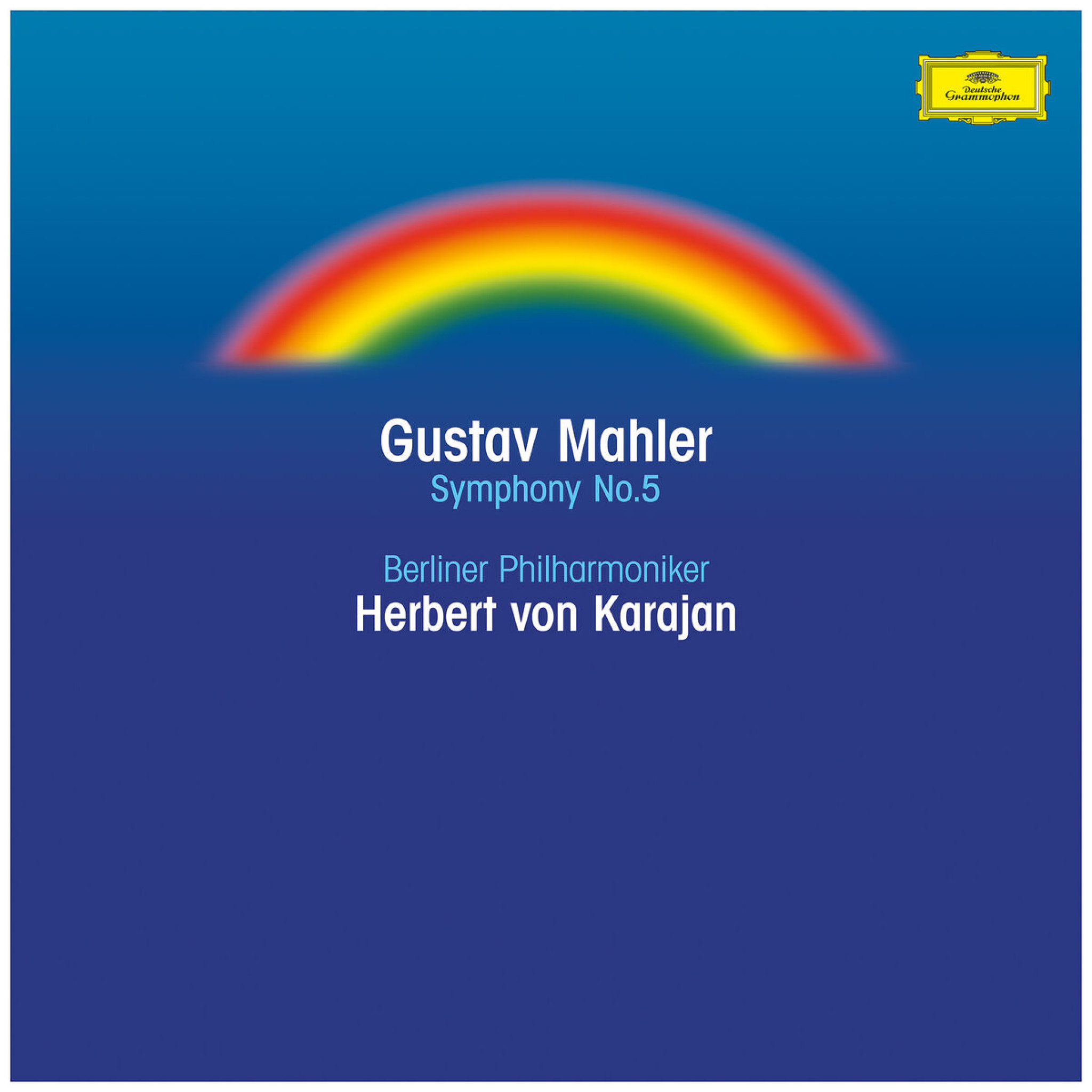

Matthies designed so many iconic album covers, including a plethora for DG, including for the groundbreaking Avant-Garde series and Karajan’s Bruckner and Mahler recordings. He had an uncanny knack of coming up with the perfect graphic elements that suggested and encapsulated the music on the record but were also a work of art in their own right.

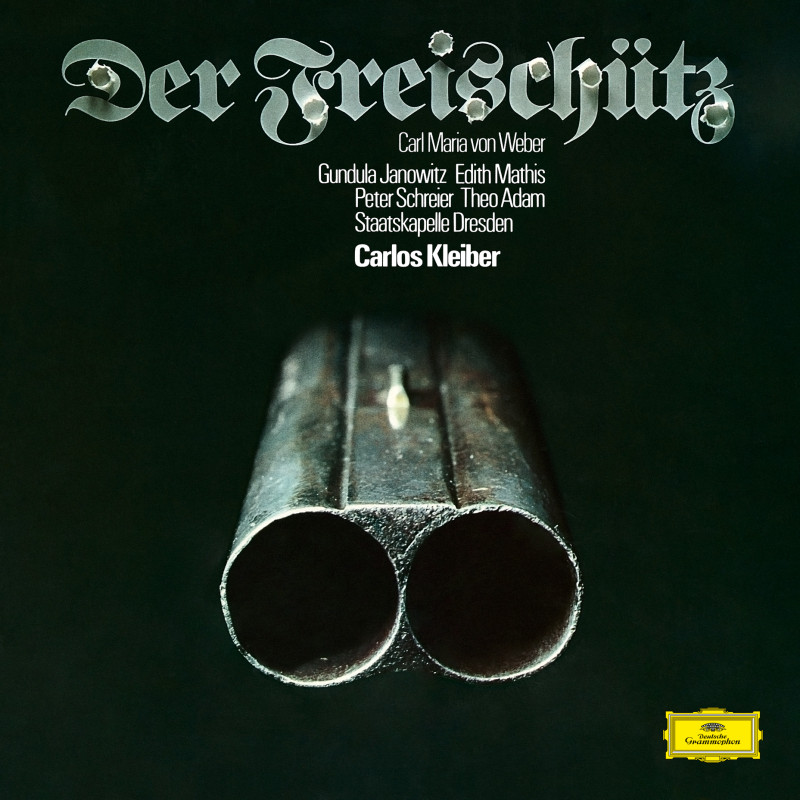

Just a few other Holger Matthies covers for DG:

The 180gram platters were all pressed at Optimal, and this time around I joined the ranks of the Optimal malcontents when I did indeed have a serious problem, with side 2 of Pelleas: a clearly visible series of scuffs and scratches that gave rise to serious audible scratching for a good few minutes. Almost definitely the result of mishandling at the plant.

Otherwise my set was fine. DG replaced this disk immediately, and has told me repeatedly that they will do whatever it takes to replace defective copies for customers. (This, of course, does not ameliorate the annoyance and expense of doing this for all concerned). However, I will just mention here that anecdotally I have been hearing that many purchasers of the Original Source (including devoted regulars) have had persistent problems with flaws in their copies. Given the kind of near perfect QC that other pressing plants like RTI and QRP offer, I think Optimal needs to seriously up their game. Not only are they letting down the customer, but they are also letting down their client, DG, which is no doubt paying handsomely for Optimal’s services.

Back to the positives…

All in all this is a stunning reissue, enhancing in every way what was already - in my opinion - the most important release in the history of Deutsche Grammophon. The folks at DG and Emil Berliner Studios have outdone themselves here. It’s a limited edition of 3300 so do not dilly dally. It will sell out. Anecdotally I am already hearing that many are truly thrilled to be discovering this music in such compelling performances and stunning sound.

As essential as any records in my entire collection.

Production Credits (same for all four records):

Producer: Dr. Hans Hirsch

Recording Supervisor: Hans Weber

Recording Engineer: Günter Hermanns

Cover Design: Holger Matthies

Sleeve Notes by H.H. Stuckenschmidt

AAA Reissue mixed by Rainer Maillard and cut by Sidney C. Meyer at Emil Berliner Studios directly from 4 and 8-track masters

Pressed on 180gram vinyl at Optimal

Limited numbered edition of 3300 copies

Product Managers: Johannes Gleim, Julian Kreuzkam

Editor: Annette Nubbemeyer

Reissue Design: Nikolaus Boddin

Deutsche Grammophon GmbH

Catalogue Number: 00289 486 7248

Available for purchase at Acoustic Sounds.

THE SACD ALTERNATIVE

These recordings were previously released in two high definition SACD editions.

The first, single hybrid CD/SACD disc from 2009 presented three works from the set: Verklärte Nacht, Webern’s Passacaglia, and Berg’s Three Orchestral Pieces. I’ve not heard this, but no doubt it conforms to the high audio standards of other hybrid Esoteric releases.

The second, 2-disc single-layer SACD-only version from Japan, released in 2021, was part of the series of superb Emil Berliner Studios remasters/remixes of the DG catalogue that paved the way for the Original Source Series on vinyl. These SACD releases were the first time that anyone had gone into the back catalogue and represented more fully than hitherto what was actually on the original master tapes, versus sonically compromised mix-downs. The SACD version of the Karajan/Second Viennese School set was revelatory, and I thought would never be surpassed. However, with the advent of the Original Source series, AAA mastered and cut directly from the 4 and 8-track master tapes, incorporating the original surround tracks made for a putative quadraphonic release, the game has changed. Fine as that SACD set is (and it is very fine indeed, and many with a good digital set-up may not feel the need to acquire the new vinyl version) it has now been superseded.

FURTHER LISTENING AND READING

While this set is all that many of you will need for their exploration of the Second Viennese School, it will spur some to explore this repertoire further. In Part 2 I discussed some other recordings that had preceded the Karajan set (and a few that came afterwards), but here I want to mention a few others - both on LP and CD - that will take you further along your journey into the birth of this particular strand of 20th century modernism.

I think for many the one additional work by Schoenberg it would have been nice to hear Karajan and the Berliners tackle was the 5 Orchestral Pieces Op. 16. This is Schoenberg in full expressionist, atonal mode from 1909, and was first performed in London in 1912 to a stunned and partly hissing reception at the London Proms. In rehearsal, conductor Henry Wood apparently instructed the players: "Stick to it, gentlemen! This is nothing to what you'll have to play in 25 years' time.”

If you have the remastered Pierre Boulez CBS/Sony box, his rendition is excellent. On vinyl the go-to has to be the Antal Dorati LP on Mercury Living Presence I mentioned in Part 2.

This is probably the best place to mention that marvelous Speaker’s Corner reissue of Dorati’s three Second Viennese School and beyond records, an essential acquisition for the vinyl collector of this repertoire.

As I also mentioned in Part 2, I really like the James Levine survey with the BPO of selected Second Viennese School works

Oddly the 5 Orchestral Pieces do not feature in Giuseppe Sinopoli’s fine 8-CD survey of the Second Viennese School with the great Dresden Staatskapelle Orchestra on Teldec/Warner, an excellent way to dive further into this repertoire. This set includes very good recordings of a few important works by Schoenberg I did not get into earlier: Gurrelieder - his massive late-Romantic dramatic oratorio - and Pierrot Lunaire - his groundbreaking, influential song cycle for vocalist engaging in speech-song with a small instrumental ensemble. Other important pieces like the First Chamber Symphony and Erwartung also feature.

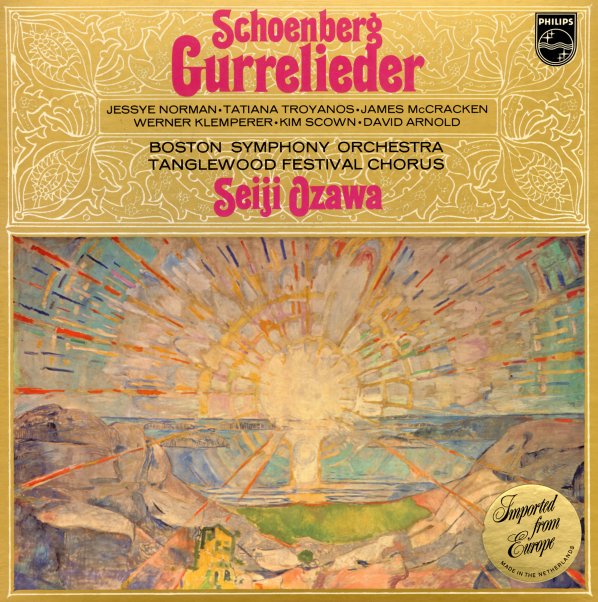

Fine as the Sinopoli Gurrelieder is, especially in the orchestral department, the singing is simply not up to the level of the two long established benchmark versions. Going back to the analogue vinyl era you have one of Seiji Ozawa’s finest recordings on Philips with the matchless cast of Jessye Norman, James McCracken, Tatiana Troyanos with the Boston Symphony on top form. If Decca/Philips were to ever get into the AAA vinyl reissue game, this would be a prime candidate for the deluxe Original Source-style treatment. Hell, it’s even got Otto Klemperer’s son Werner (Colonel Klink in Hogan’s Heroes) as the Speaker.

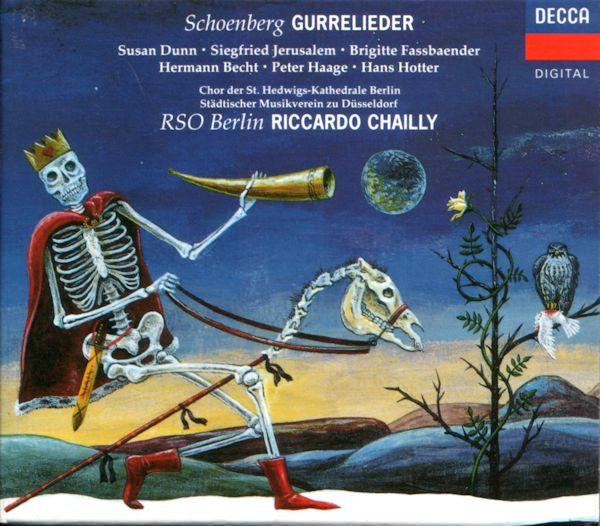

The other benchmark, on CD only, is Riccardo Chailly’s stunning Decca version with the RSO Berlin from a decade later in 1990. The engineering team is led by the legendary James Lock, responsible for so many classic Solti records. The alternately delicate and massive sound fills every nook and cranny of the Jesus-Christus Kirche, scene of so many DG recordings. Susan Dunn, Siegfried Jerusalem and Brigitte Fassbaender head the formidable cast, with the great Hans Hotter (Wotan in Solti’s Ring cycle) as a duly authoritative Speaker. It nearly blew the roof off when I re-listened to it for this survey.

Either one of these Gurrelieder recordings will more than satisfy.

Pierrot Lunaire is more of an acquired taste, and, depending on your tolerance for speech-song, will either compel your attention or drive you nuts. The big difference lies in how much the singer actually sings, and how much they speak, and how much they find the happy medium to put over the sprechgesang (speaking singing) Schoenberg specified in his score. Soloists vary enormously. This is all very much down to personal taste, but as good a place to start as any is Boulez’s later recording on DG with Christine Schäfer. I am also partial to Jan DeGaetani’s account on Nonesuch vinyl. She actually came to sing at my English high school in the 70s, a very memorable recital. A great singer taken from us far too soon.

Staying with Schoenberg, let me reiterate those excellent recordings I mentioned in Part 2 of the Piano Concerto with Mitsuko Uchida, and of the Violin Concerto with Hilary Hahn, both superb CDs.

Obviously completists will want to acquire as many Boulez accounts as they can, mostly spread across CBS/Sony, DG and Erato, but also on a clutch of other smaller labels. His later DG account of the opera Moses und Aaron is as definitive as it gets, and Boulez completists will also want to seek out his account of Pelleas und Melisande on DG with the Gustav Mahler Youth Orchestra.

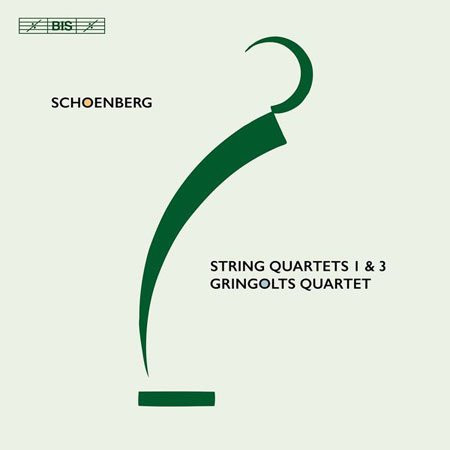

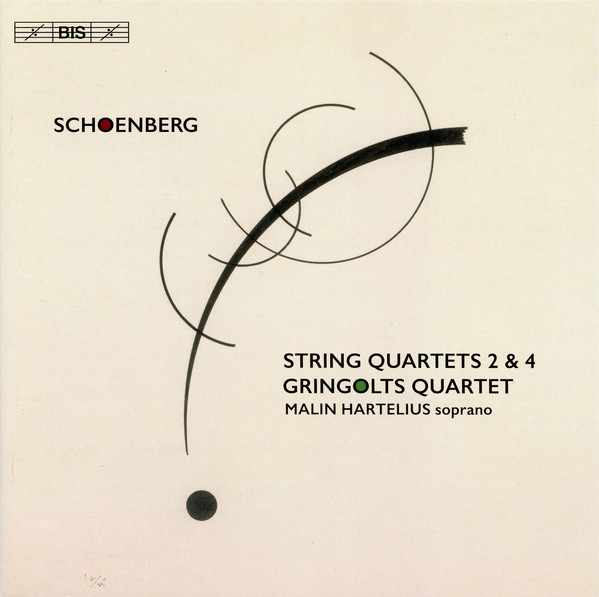

As I mentioned in Part 2, the recent accounts on BIS hybrid CD/SACD of the string quartets by Ilya Gringolts and his colleagues in the Gringolts Quartet wipe the floor with all previous versions, both in terms of performance and sonics which really allow this dense music to breathe.

The piano music is well represented by Glenn Gould on CBS/Sony, and by Pollini on DG (let’s hope for an Original Source reissue, otherwise go for the CD over OG vinyl).

Literally as I am tapping this, a parcel has arrived from the Berlin Philharmonic label, containing a copy of that orchestra’s contribution to the Schoenberg 150th Anniversary celebrations. This features some of his more ornery works, including those Variations premiered by the orchestra in 1928 under Furtwängler, plus the rarely done oratorio Die Jacobsleiter; plus you get the more familiar and accessible Violin Concerto and Verklärte Nacht. Can’t wait to audition and compare - stay tuned for my review.

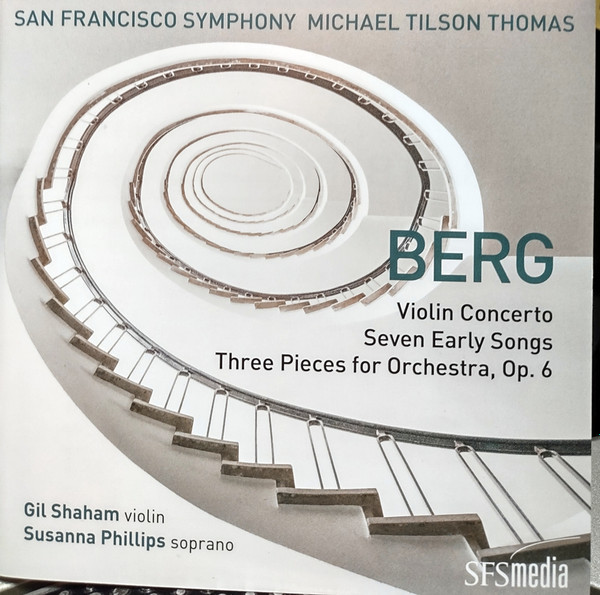

With Berg you have to have the Violin Concerto, and one of my favorite versions of recent years is that done by Gil Shaham with Michael Tilson Thomas and the San Francisco Symphony, available as a hybrid CD/SACD on the orchestra’s own label. I actually heard them doing this live in concert on the tour that produced this recording, and it was a ravishing account.

From an earlier era the Itzhak Perlman version on DG with Ozawa in Boston has long been my go to, and sounds decent enough on its original vinyl version. It would sound even better in an Original Source reissue (hint, hint…)

For one of the greatest operas ever written, Berg’s Wozzeck, go for the version on DG by Claudio Abbado.

I also have great fondness for the 60s Karl Böhm account, also on DG. Abbado’s series of Berg releases on DG, starting in 1971 and reaching into the digital era, offer a great survey of more of his works, including the important song cycles.

For the completed version of Lulu, it has to be Boulez’s premiere recording on DG. I saw a stunning production in 1981 of this by the legendary Götz Friedrich at the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, conducted searingly by Colin Davis. A remarkable piece of modernism that deserves to be better known.

Berg’s formidable Piano Sonata No. 1 is given a definitive outing by Pollini on a digital DG release from 1994, paired with a superb account of Debussy’s Études.

With Webern you have to go with either one of or both of Boulez’s surveys, on CBS/Sony, or DG (more all-encompassing than the CBS set). That way you acquire all the odd little pieces and songs that make up the bulk of his output - the orchestral works were not a priority. The single LP of his string quartets by the Quartetto Italiano is an easy recommendation. A great single CD survey of Webern’s orchestral music is offered in excellent sound on Decca, with Christoph Dohnanyi and the Cleveland Orchestra. Originally issued coupled with Mozart’s last symphonies (the version I have - and I love the juxtaposition of the two radically different composers), these are a great way to get a clutch of Webern orchestral music on one disc in Decca’s finest modern, albeit digital, sound.

But in the works represented, nothing beats the Karajan selection in this box.

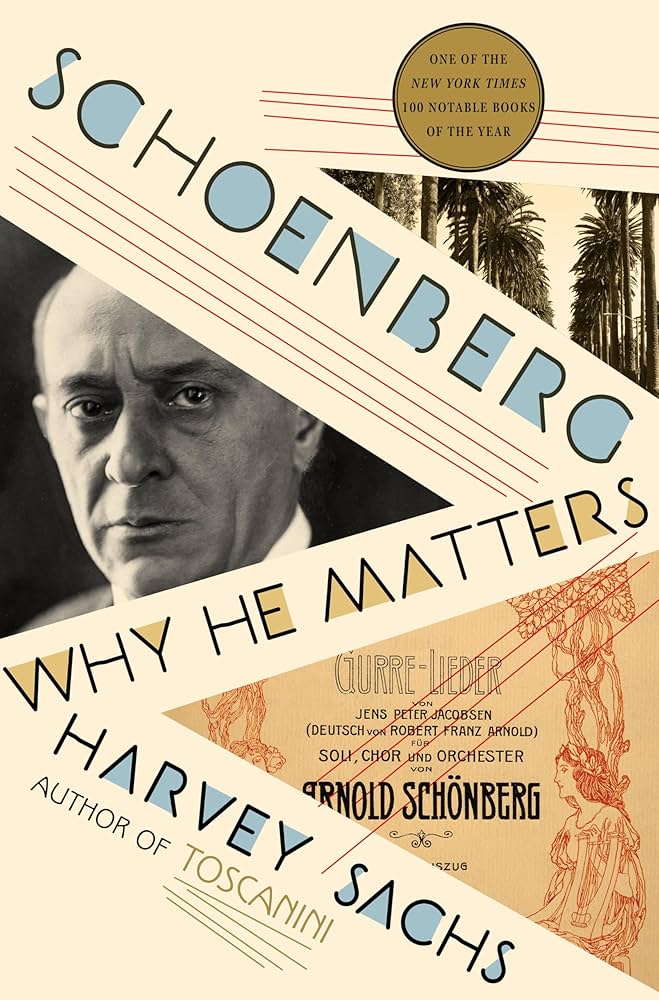

As far as further reading is concerned, the one book I can most heartily recommend is the one I have quoted from a few times for these articles: Schoenberg - Why He Matters by Harvey Sachs. Described as a “lyrical biography” (whatever that may be), nevertheless I found this to be the most inviting way into the story of this elusive figure, whose personality was as challenging as his music. Sachs is a superb “everyman” guide to the life and the music, and you will learn a lot - as well as be inspired to explore the music further, the best possible reason for reading a book like this. Schoenberg is still such a misunderstood and relatively unknown figure, whose music is rarely played, who just happened to change the course of modern music. Read this book, listen to the Karajan set, and you will begin to understand just how extraordinary Schoenberg and his pupils were, and why their accomplishments demand our fullest attention and consideration.

And if you want to learn more about Schoenberg's later life in California, I recommend this fascinating essay by Alex Ross in The New Yorker. Here's a taster:

Of the thousands of German-speaking Jews who fled from Nazi-occupied Europe to the comparative paradise of Los Angeles, Arnold Schoenberg seemed especially unlikely to make himself at home. He was, after all, the most implacable modernist composer of the day—the progenitor of atonality, the codifier of twelve-tone music, a Viennese firebrand who relished polemics as a sport. He once wrote, “If it is art, it is not for all, and if it is for all, it is not art.” The prevailing attitude in the Hollywood film industry, the dominant cultural concern in Schoenberg’s adopted city, was the opposite: if it’s not for all, it’s worthless.

Yet there he was, the composer of “Transfigured Night” and “Pierrot Lunaire,” living in Brentwood, across the street from Shirley Temple. He took a liking to Jackie Robinson, the Marx Brothers, and the radio quiz show “Information Please.” He played tennis with George Gershwin, who idolized him. He delighted in the American habits of his children, who, to the alarm of other émigrés, ran all over the house. (Thomas Mann, after a visit, wrote in his diary, “Impertinent kids. Excellent Viennese coffee.”) He taught at U.S.C., at U.C.L.A., and at home, counting John Cage, Lou Harrison, and Oscar Levant among his students. Although he faced a degree of indifference and hostility from audiences, he had experienced worse in Austria and Germany. He made modest concessions to popular taste, writing a harmonically lush adaptation of the Kol Nidre for Rabbi Jacob Sonderling, of the Fairfax Temple. He died in Los Angeles in 1951, an eccentric but proud American.

And in conclusion...