Decoding the Dawn of Modern Music - The Original Source Offers Fresh Illumination of Karajan and the BPO's Groundbreaking Survey of the Second Viennese School - PART 2

20th Century Modernism and the Gramophone

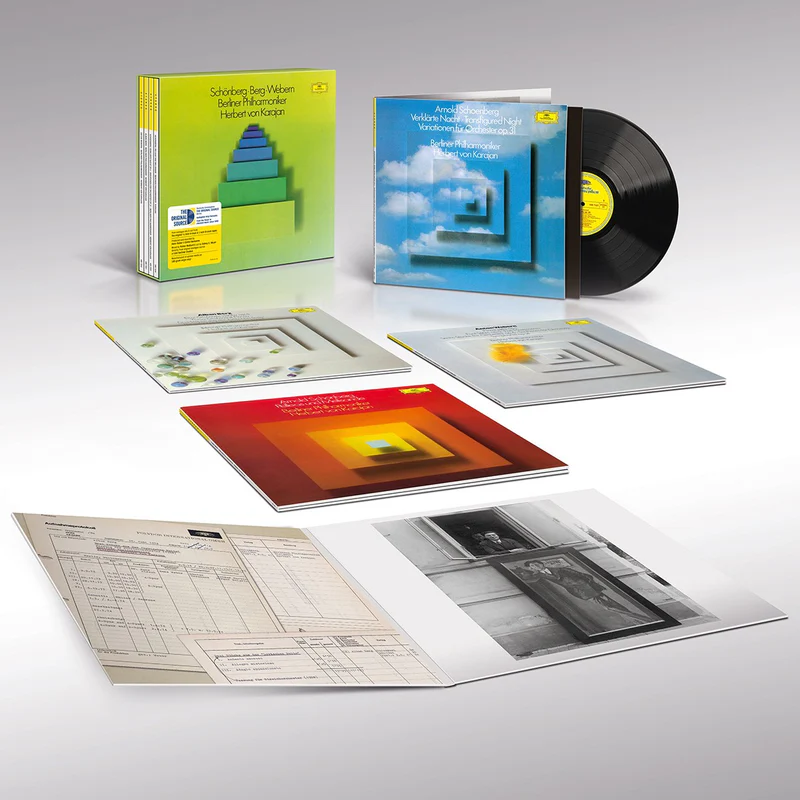

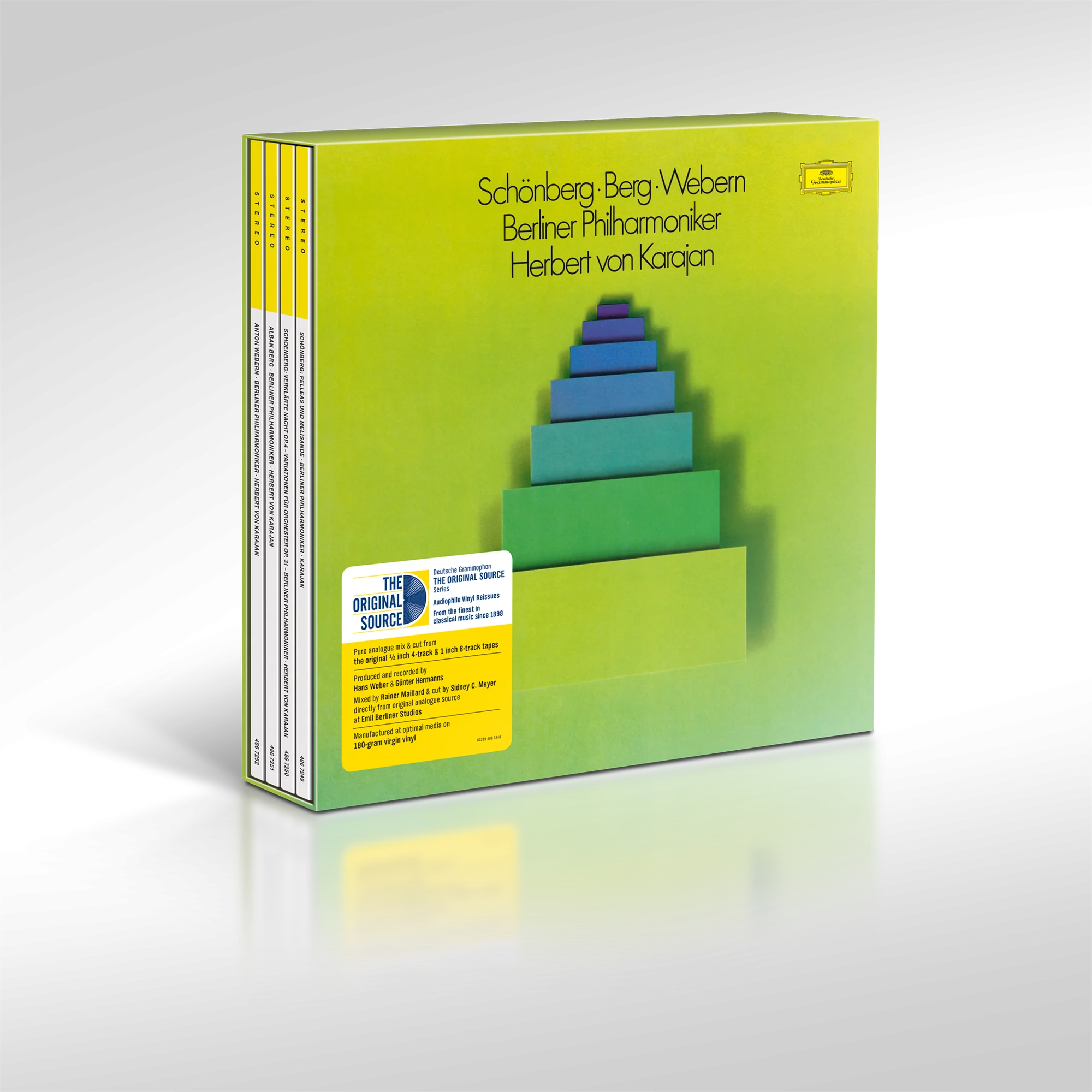

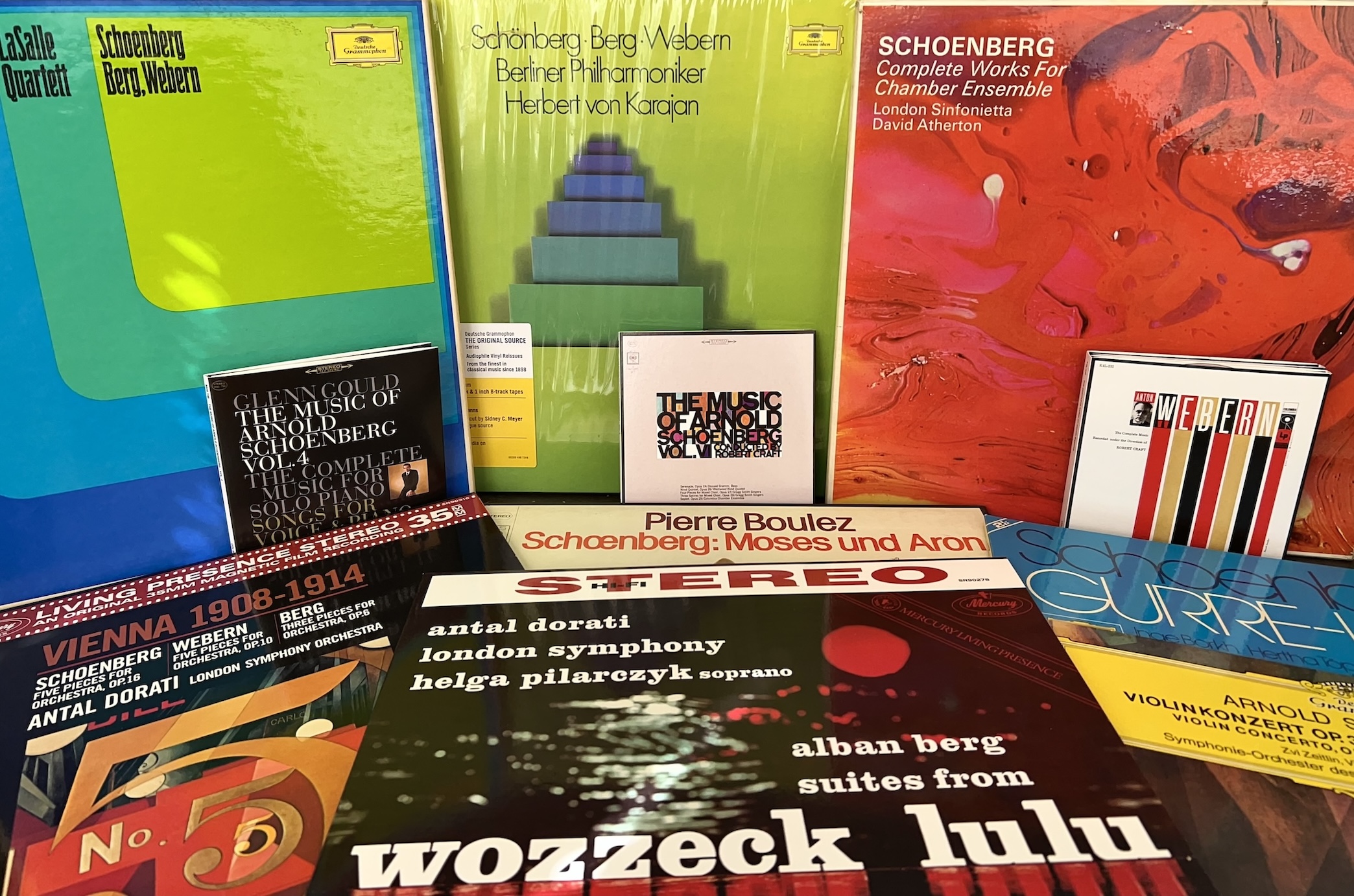

From the moment it became clear that the Original Source Series was reinvigorating DG’s back catalogue for vinyl in the exceptional manner in which it has been done, I was hoping this set would get reissued. I am sure many of our regular readers of our classical coverage familiar with these recordings felt the same.

Surveying the entire treasure trove that comprises the Deutsche Grammophon catalogue, full to the brim with benchmark performances by the world’s greatest classical performers over the last 130-plus years, one is brought face-to-face with the full breadth of the classical repertoire.

Yet if you asked me to name the one recording (or set of recordings - this was originally issued as a box set, later as individual LPs) which I would preserve from the entire DG catalogue, this group of four LPs would be it. Yes, it is truly that significant - and that mesmerizing a listen.

And to have these recordings which I have treasured and returned to over and over again since I bought the original box set the week it was released in 1974, now given the full Original Source remastering cut directly AAA from the 4 and 8 track master tapes is, for me (and I am sure for many others), like receiving manna from heaven.

So why is this such an important release, aside from the historical significance of these composers and the singular nature of their music?

Let’s begin with the historic place this set occupies not only within the DG catalogue, but within the classical catalogue in general.

When they were first released in 1974, these recordings literally changed people’s minds about the music contained therein, and helped music lovers engage with repertoire many - if not most - of them had either given up on or not been able to sample at all in first rate renderings. At the time, this music was rarely performed or recorded.

Karajan and the Berliners blew past the considerable technical difficulties of actually being able to play the music with authority (and without errors), and made it come alive as sensuously and dramatically as any war horse in their catalogue. Given this music’s foundational role in the development of 20th century music and beyond, be it classical or otherwise, that in itself made this box seminal, and essential.

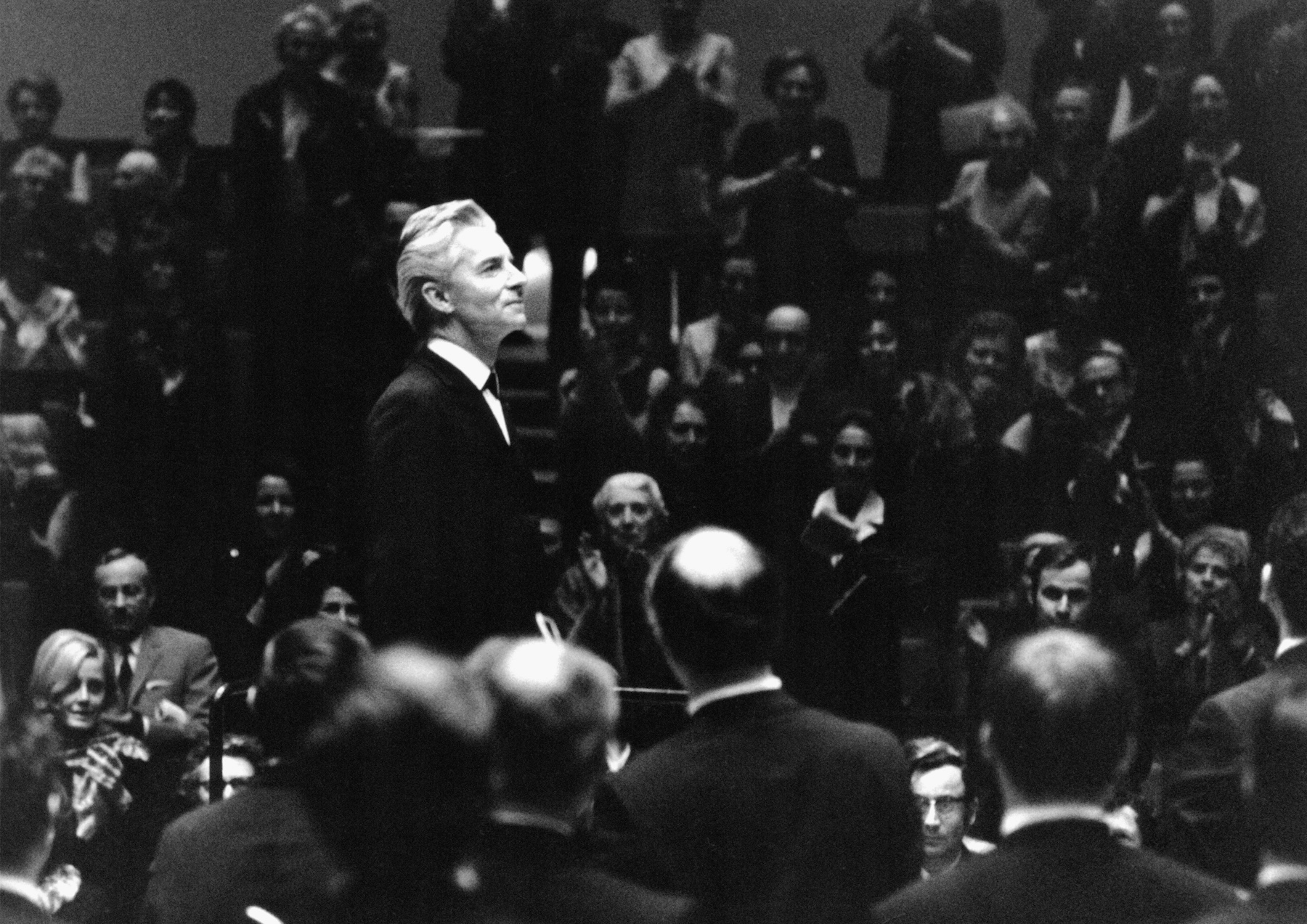

Herbert von Karajan in the early 1970s (Photo: Siegfried Lauterwasser)

Herbert von Karajan in the early 1970s (Photo: Siegfried Lauterwasser)

I will also add that when it comes to assessing the contribution and legacy of one of the most important conductors and creative - and, lest we forget - commercial partnerships in the history of classical music (and the classical record industry), this may well be the most important group of records made by Herbert von Karajan and the Berlin Philharmonic - which is saying something. There’s a certain irony here because Karajan saw himself primarily as the embodiment of the traditional German classical tradition, part of why he was always returning to the music of Bach, Beethoven, Mozart, Brahms, Richard Strauss and Bruckner, recording their works over and over again (as well as the operas of Wagner). In contrast, the music of the Second Viennese School literally blows up that tradition.

Yet I am not alone in believing that, fine as Karajan’s renderings of the traditional German repertoire were (often being considered benchmarks of their era and beyond), it was in the off-the-beaten path, non-Germanic, repertoire that he truly shone, producing his most essential and enduring records: for example, Prokofiev’s 5th Symphony; Shostakovich’s 10th Symphony; Honegger’s Second and Third Symphonies (ripe for OSS reissue); Debussy and Ravel orchestral works, Debussy’s Pélleas et Mélisande; Mahler’s 6th and 9th Symphonies…

The irony lies in the fact that the music contained in this set - that Karajan presented so persuasively, even spellbindingly - essentially blew up the harmonic and formal precepts of the German classical tradition he so admired and was steeped in. That tradition had given rise to over two centuries of masterpieces, yet here were Schoenberg and his acolytes - Alban Berg and Anton Webern - attempting to replace it with a completely new way of doing things. This was to be a whole new German classical tradition for the new century, the so-called “Second Viennese School”. It was designed to be the modern equivalent to the First Viennese School of Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven, the progenitors of German hegemony for another 200 years of classical art music.

But that’s not how things worked out. Atonality and serialism, the brainchildren of Schoenberg in reaction to what he felt had become the redundant excesses of late Romantic music (which he himself composed brilliantly in his early years), may have dominated progressive thought in classical music for five decades or so after he forged his new compositional method, but both atonality and serialism are now perceived as something of a dead end. That Karajan, of all people, should have made the best argument for this music that destroyed what he valued most - the German classical tradition - is the irony of all ironies.

When I was studying music in college in the early 1980s, academia, and by extension critical orthodoxy, was predominantly all about atonality and serialism, composers like Pierre Boulez, Luciano Berio, Karlheinz Stockhausen. Music cast in more traditional tonal terms by people like Britten, Hindemith, Prokofiev, Copland and Shostakovich was considered the last gasp of a now archaic system. (Stravinsky remained an island unto himself in many ways, forging his own revolutions while remaining within the precepts of tonality, at least until he embraced his own version of serialism later in life). With the rise of the minimalists like Philip Glass, Steve Reich, and John Adams in the 1980s, Schoenberg’s serialism was rejected in favor of an embrace of pre-Romantic, even pre-Classical period, harmonic simplicity, with simple repeated chords in identifiable tonal keys being repeated ad infinitum and, often (let’s be frank), ad nauseam. (Things got more interesting as the minimalists, especially John Adams, embraced more complex procedures and harmonic approaches).

As traditional Western art music struggled in the mid-20th century to find audiences for this forbidding “avant-garde” music in the face of the competition from the harmonic and rhythmic directness of rock and jazz (before the latter followed the classical avant-garde down the rabbit hole in the form of free jazz), a similar struggle unfolded within the classical record industry. Record labels did not want to be seen to be ignoring this avant-garde movement, which had a small but fervent following, yet at the same time the market for this music was small and specialized, and making records was an expensive process.

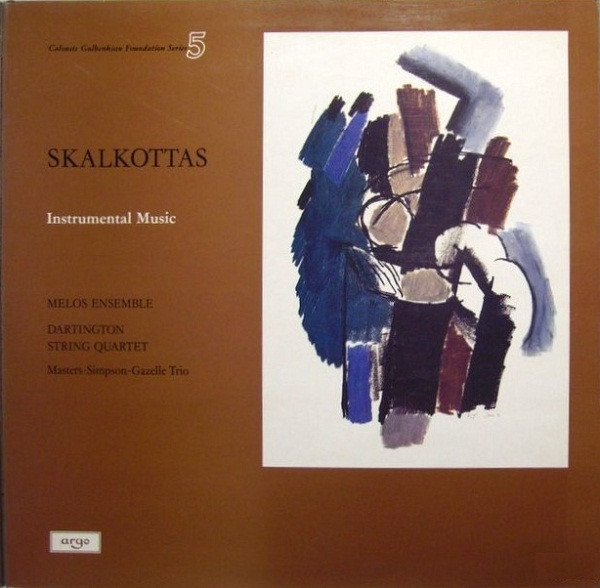

As a way of representing this “difficult” music (acknowledging it would mostly lose money but have appeal amongst hard-core collectors and dedicated avant-gardists), most of the major classical labels through the 1960s and 70s developed niche labels and catalogues for this music, often funded in part by private foundations. On Decca’s Argo imprint, for example, you had the Gulbenkian Foundation’s series of records, focusing mainly on British composers.

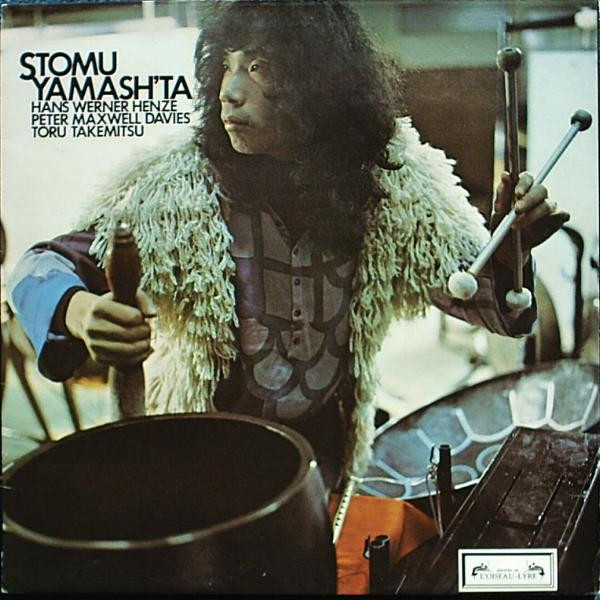

In 1972, the Decca owned L’Oiseau-Lyre imprint (soon to become the home for the Academy of Ancient Music and other nascent period instrument groups) took one of its few excursions away from early music to release a superb album of contemporary percussion music featuring the great Japanese virtuoso Stomu Yamash’ta.

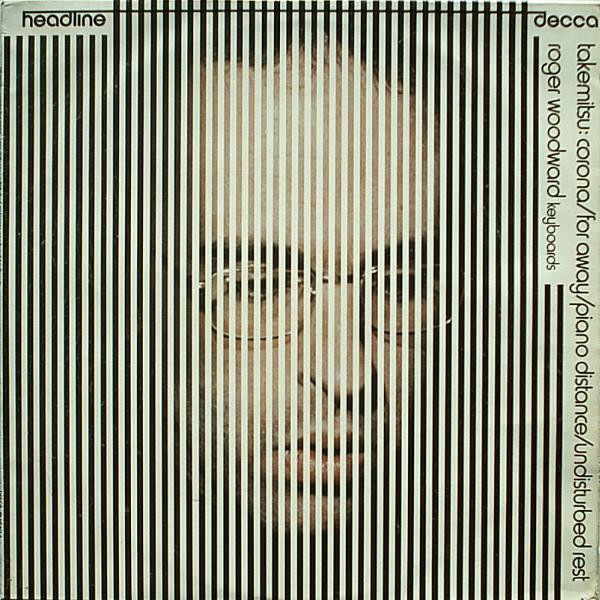

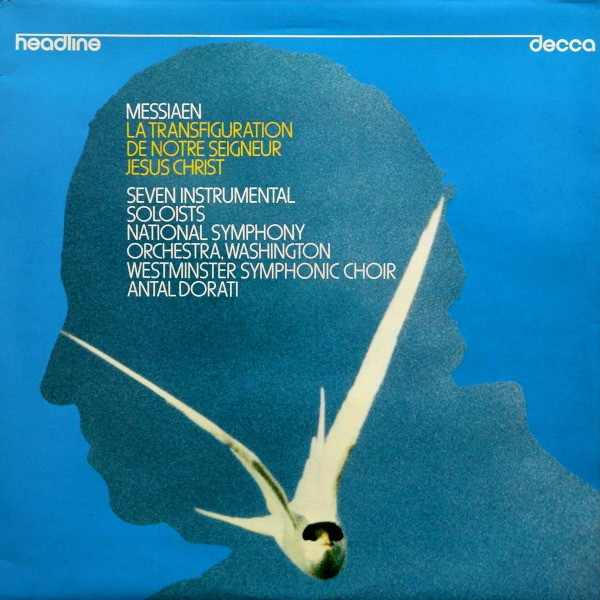

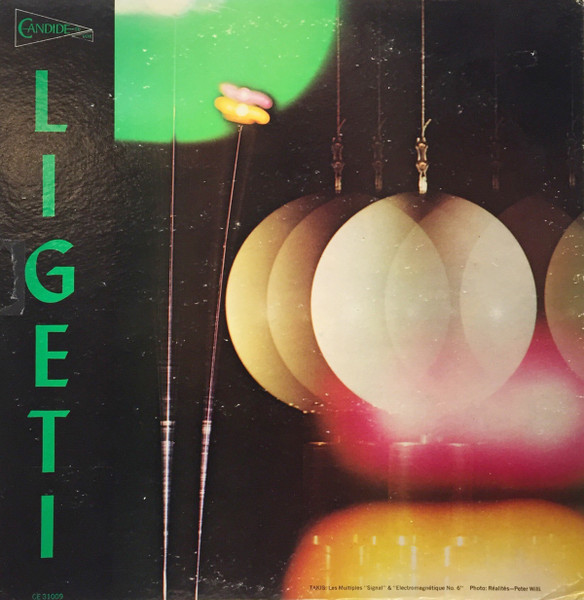

Decca also began its own Headline imprint, with magnificent, genuinely audiophile albums of composers like Gyorgi Ligeti, Harrison Birtwistle, and Toru Takemitsu.

Antal Dorati’s still benchmark rendering of Messiaen’s massive choral work, La Transfiguration de Notre Seigneur, is an audiophile spectacular, whose opening gongs and tam-tams detonate and shimmer in your listening room. All these Decca imprints released very well recorded albums you can often pick up today for a few dollars in the used bins.

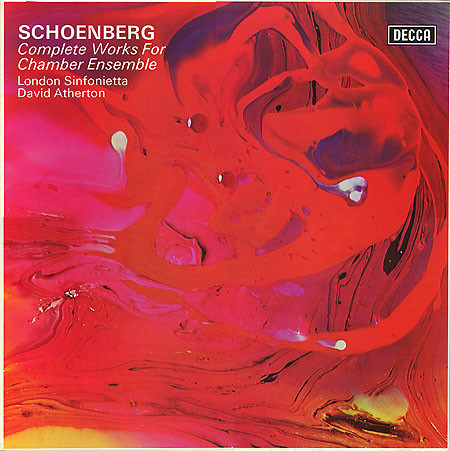

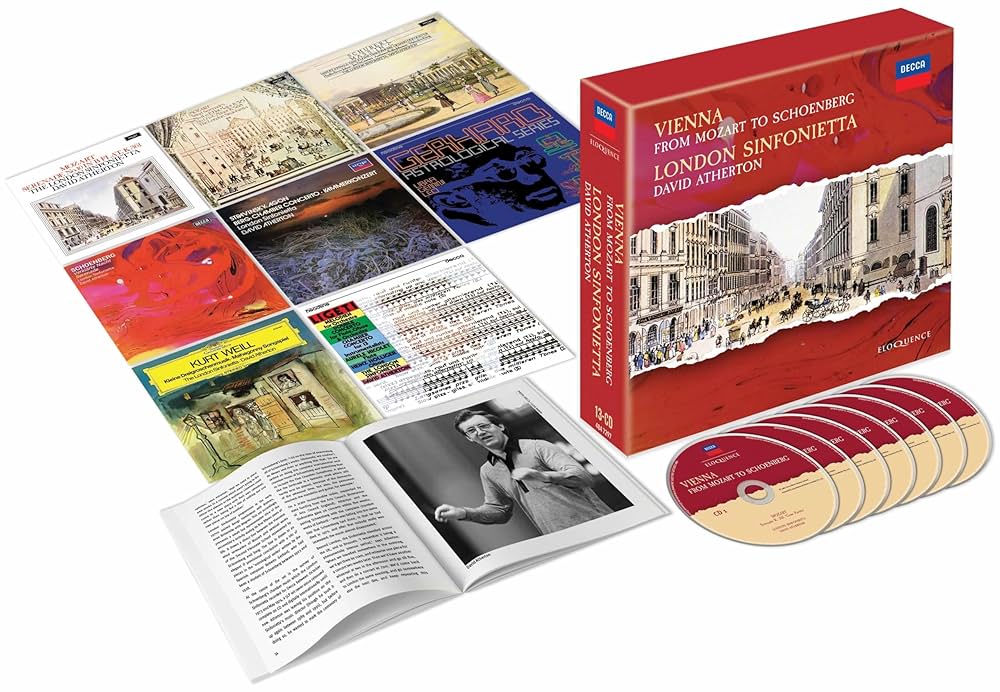

Maybe the most significant Second Viennese School release came out the same year as Karajan’s set, in 1974. Decca turned to England’s premier modern music ensemble, the London Sinfonietta, and conductor David Atherton for a deluxe 4LP survey of Schoenberg’s chamber music. This is an essential volume for fans of this music, either in its original vinyl form…

… or in its recent reincarnation in an Eloquence CD box gathering together all of these performers’ indispensable releases.

These include a benchmark survey of Kurt Weill originally on DG, likewise Decca Headlines of Ligeti and Roberto Gerhard, and a splendid coupling of Berg’s Chamber Concerto and Stravinsky’s later serial masterpiece Agon (they even throw in some Mozart, Schubert and Spohr).

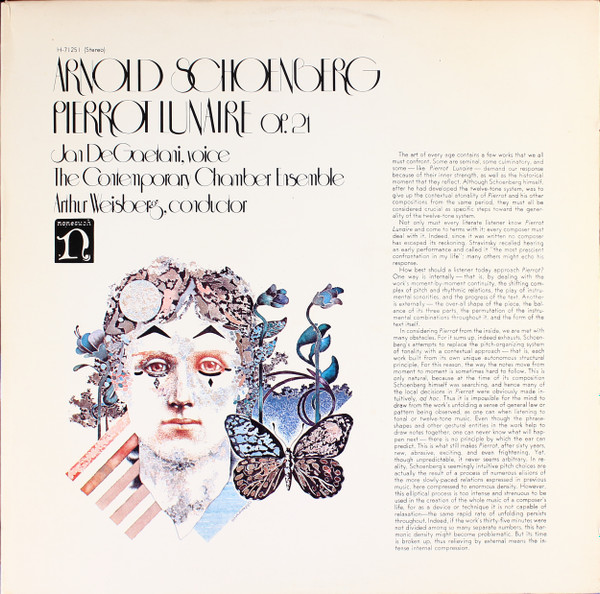

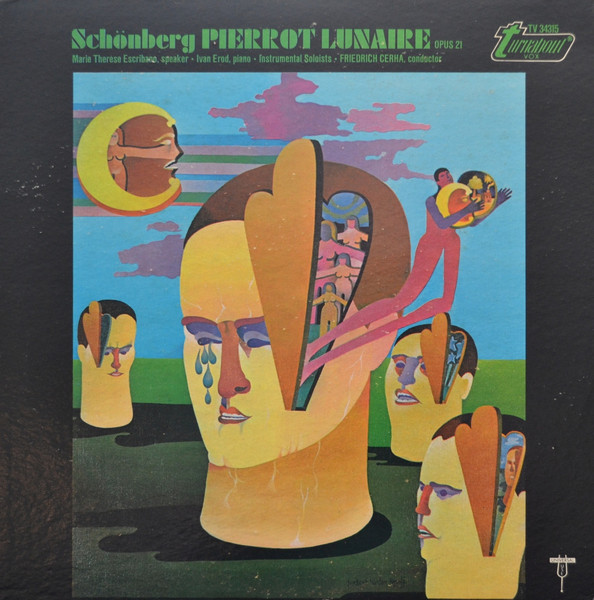

While the more familiar Schoenberg works like the original sextet version of Verklärte Nacht, Pierrot Lunaire and the Chamber Symphony No. 1 receive fine performances (but are perhaps superseded in recordings elsewhere), the real gems here are the rarer, shorter works.

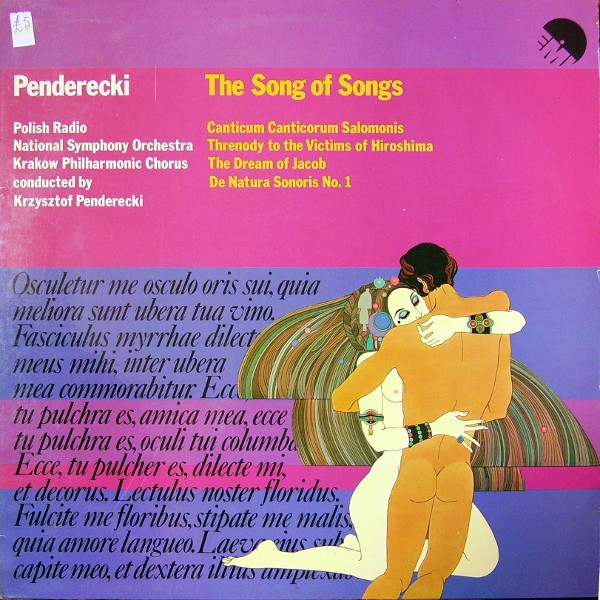

EMI started its own “out-of-the-box” series of recordings of 20th century repertoire in the 70s which - identifiable by their stylized artwork with primary colored horizontal lines - featured everything from the coruscating soundscapes of early Krzysztof Penderecki (Threnody to the Victims of Hiroshima)...

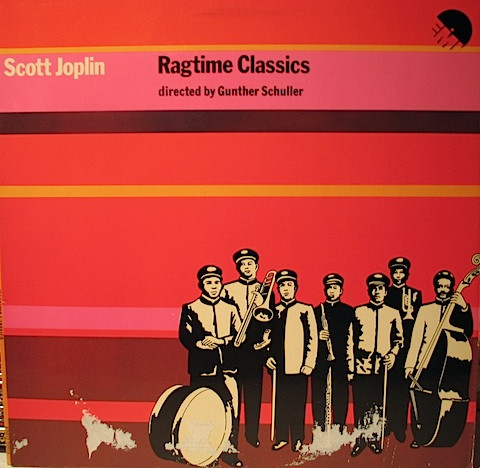

... to the then rarely performed Korngold Violin Concerto and, believe it or not, to a fabulously recorded and played album of Scott Joplin rags performed by Gunther Schuller and the New England Conservatory Ragtime Ensemble.

EMI France began its important series of Messiaen recordings in the 1960s, many of them featuring the composer himself and his wife. These were gathered together in a formidable box set a few years ago, essential for any Messiaen enthusiast.

Back on EMI UK, André Previn would lead an audiophile spectacular of the Turangalila Symphony in 1978.

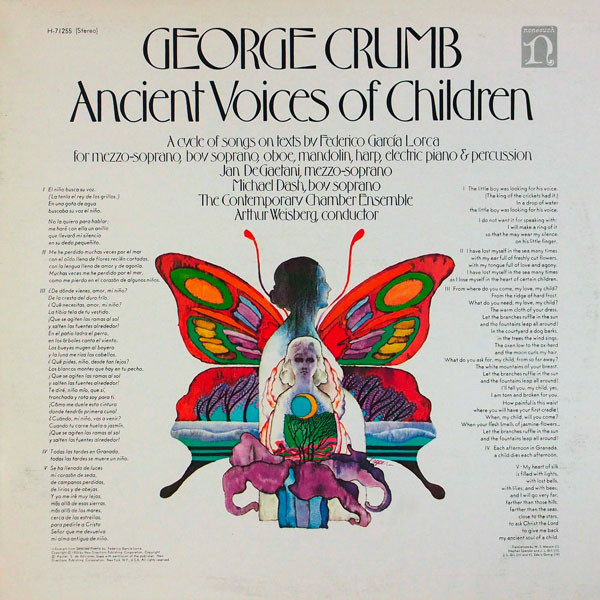

In America, labels like Nonesuch were fully onboard with the avant-garde. Nonesuch produced its own Contemporary Music series, a superbly played and recorded series of LPs, many of them engineered by the legendary team of Marc Aubort and Joanna Nickrenz. Copies with beaten up covers but immaculate records within, barely played, will show up in the used bins for a few dollars.

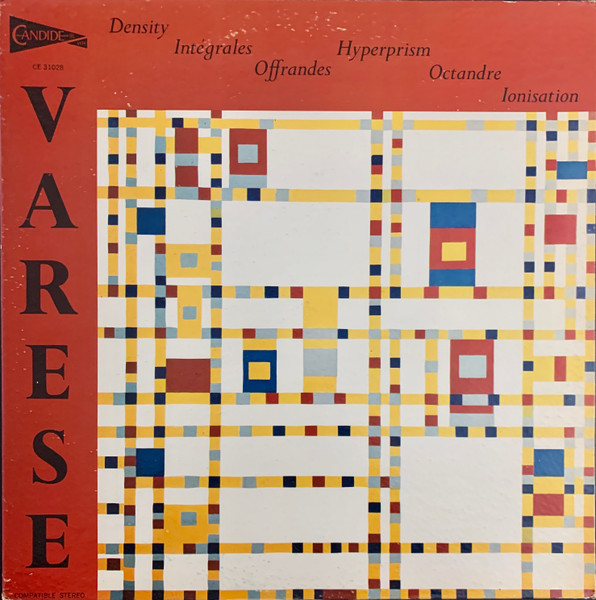

Candide was an imprint started by Vox/Turnabout, and featured a variety of new music, and its records were one of the main ways Americans discovered this repertoire.

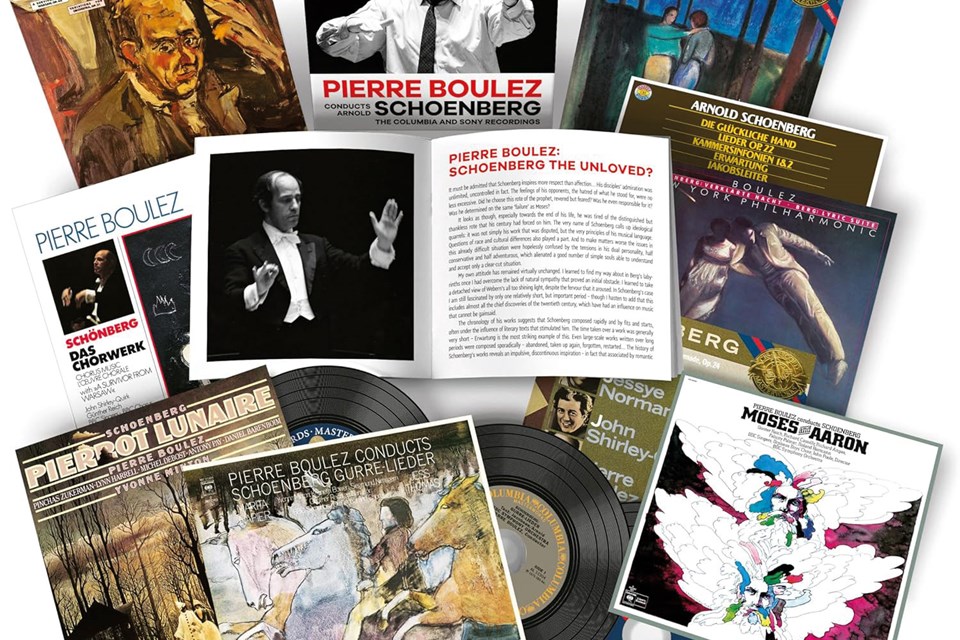

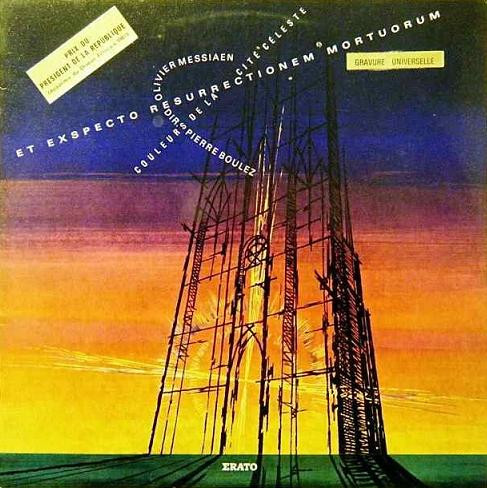

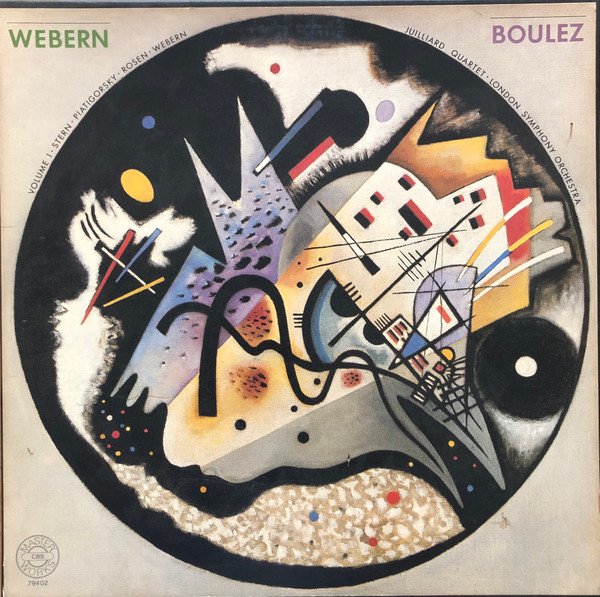

Likewise Columbia/CBS had a lifetime contract with Igor Stravinsky, then took on Pierre Boulez who was able to record his own music and launch his own groundbreaking surveys of Schoenberg, Webern and Berg, and outliers like Edgar Varèse. (Boulez also made important records for Erato in France beginning in the 60s).

CD box containing all of Boulez's Schoenberg recordings for CBS, many of which post date the Karajan set.

CD box containing all of Boulez's Schoenberg recordings for CBS, many of which post date the Karajan set.

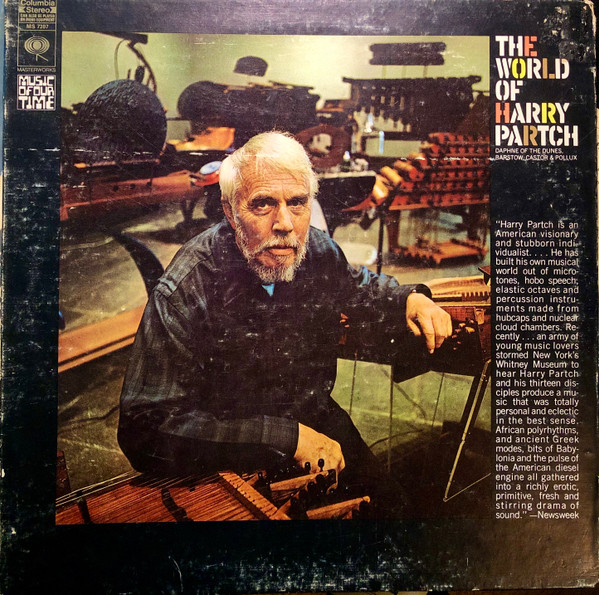

Columbia also delved into the unique sound world of Harry Partch with his panoply of invented and self-built instruments.

The label had begun its serious commitment to modern music in the 1950s with a series of pioneering records by Robert Craft (Stravinsky’s amanuensis), which encompassed the Second Viennese School. Craft also tackled a range of early music. His fascinating CBS catalogue is gathered together in an indispensable box for anyone interested in these historical corners of the classical catalogue. As with so many of these Sony boxes, the remastered sound on these recordings is superior to the original LPs

Craft’s recordings were important pioneers and place-holders, but lacked the sheer virtuosity and authority of Karajan and other later interpreters’ renderings.

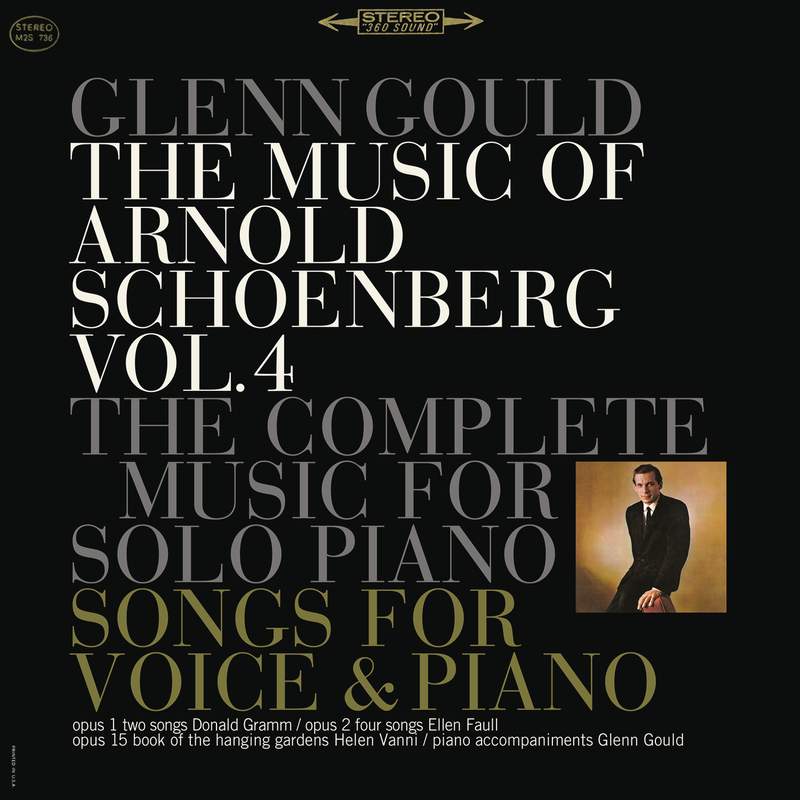

In 1966, maverick pianist Glenn Gould contributed his own set of the piano music and music for voice and piano.

Also on CBS, the Juilliard String Quartet had tackled the Schoenberg String Quartets in a series of records dating back to the 1950s. Again, the most recent Sony CD box gathers these together in excellent remastered sound. (Although my go-to for these works is the recent pair of CD/SACDs on BIS by the Gringolts Quartet).

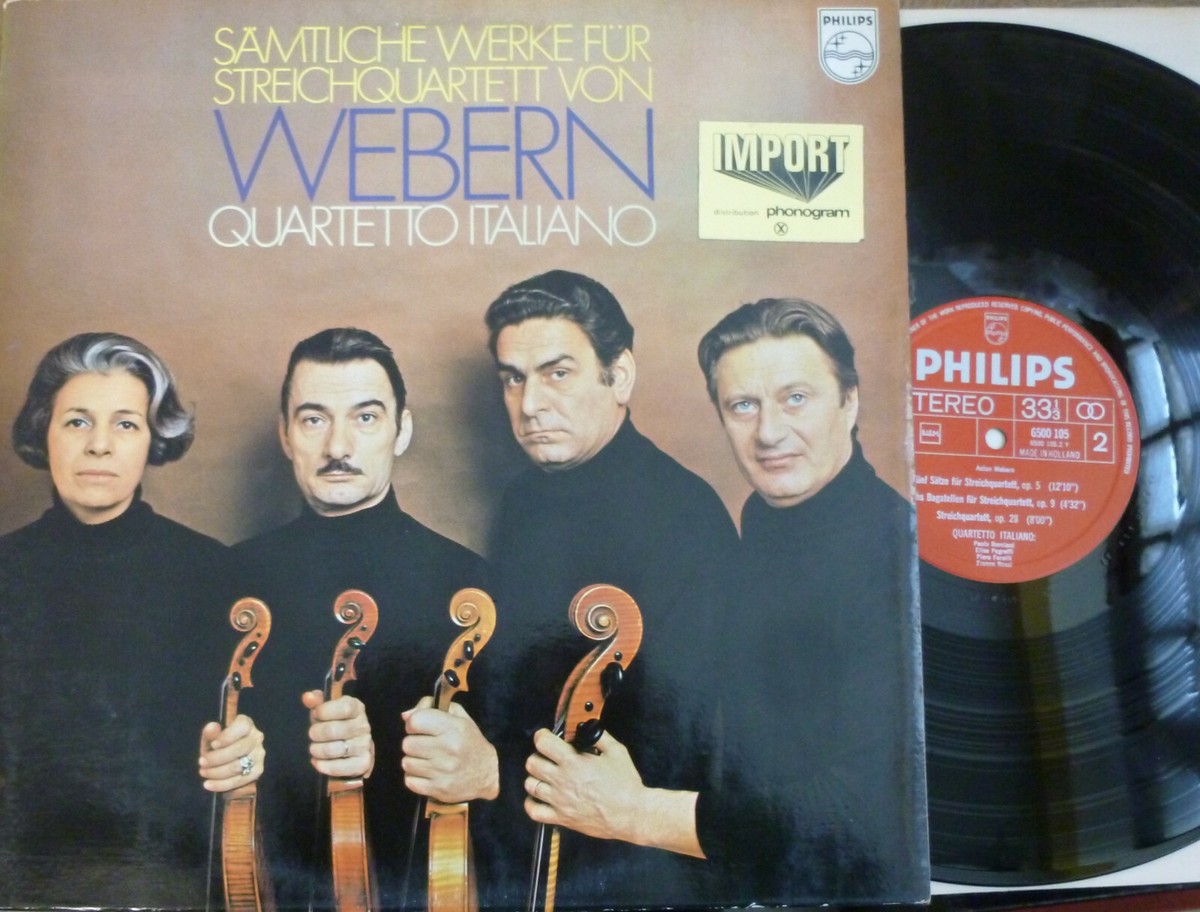

I will mention here an essential one-off record on Philips from 1970 of the Webern string quartets performed by the excellent Quartetto Italiano. This turns up regularly in the used bins for little money.

In France and Germany, labels like Vega, Erato and Wergo were fully dedicated to homegrown avant-gardists like Pierre Boulez and Karlheinz Stockhausen, whose electronic works held great crossover appeal to the progressive rock crowd.

Wergo's seminal recording of the version of Kontakte that includes piano and percussion playing with tape. For the tape version alone, see the DG release referenced below.

Wergo's seminal recording of the version of Kontakte that includes piano and percussion playing with tape. For the tape version alone, see the DG release referenced below.

Erato and Wergo will show up used in immaculate condition in the least expected places. I have yet to see a Vega release in the wild, but this is an important catalogue covering the earliest days of avant-garde repertoire on record, with many early Boulez recordings.

Deutsche Grammophon was somewhat unique in that it regularly dedicated all its resources to releases of the thorniest of modern music on its main label.

Some background. To extend its repertoire reach beyond the mainstream Baroque, Classical and Romantic eras, beginning in 1949, DG created a specialized early music imprint, Archiv. This introduced many listeners to music from the inception of the Western classical tradition with Gregorian chant in the 9th and 10th centuries, through the Renaissance and Baroque periods.

At the other end of musical history, DG was determined to represent the contemporary modern era. Beyond covering established names like Stravinsky and Bartok, the main “Yellow Label” began, from the 1960s onwards, diving into modernists like Karlheinz Stockhausen, Hans Werner Henze, John Cage, and György Ligeti; Pierre Boulez, Steve Reich, John Adams and Philip Glass followed, moving into the early 21st century. One of DG’s most important early albums of minimalism comprised a 3LP set of Steve Reich’s Drumming.

Even the film composer John Williams signed to DG in recent years (represented both by film and concert scores), along with a smattering of a newer generation who were not strictly “classical” in the traditional sense: people like Max Richter (a huge bestseller for the label, beginning with his re-imagination of Vivaldi’s Four Seasons).

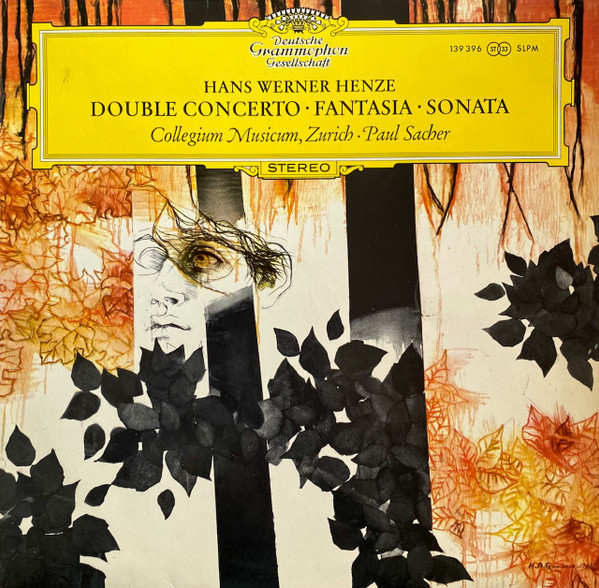

In the 1960s DG began releasing foundational recordings of iconic works by Stockhausen and Hans Werner Henze.

The tape only version of two of Stockhausen's essential electronic works. Seek out a "large tulip" pressing if possible

The tape only version of two of Stockhausen's essential electronic works. Seek out a "large tulip" pressing if possible

Paul Sacher was a major force in 20th century music, commissioning major works from Bartok, Stravinsky, Martinu and Henze - amongst others.

Paul Sacher was a major force in 20th century music, commissioning major works from Bartok, Stravinsky, Martinu and Henze - amongst others.

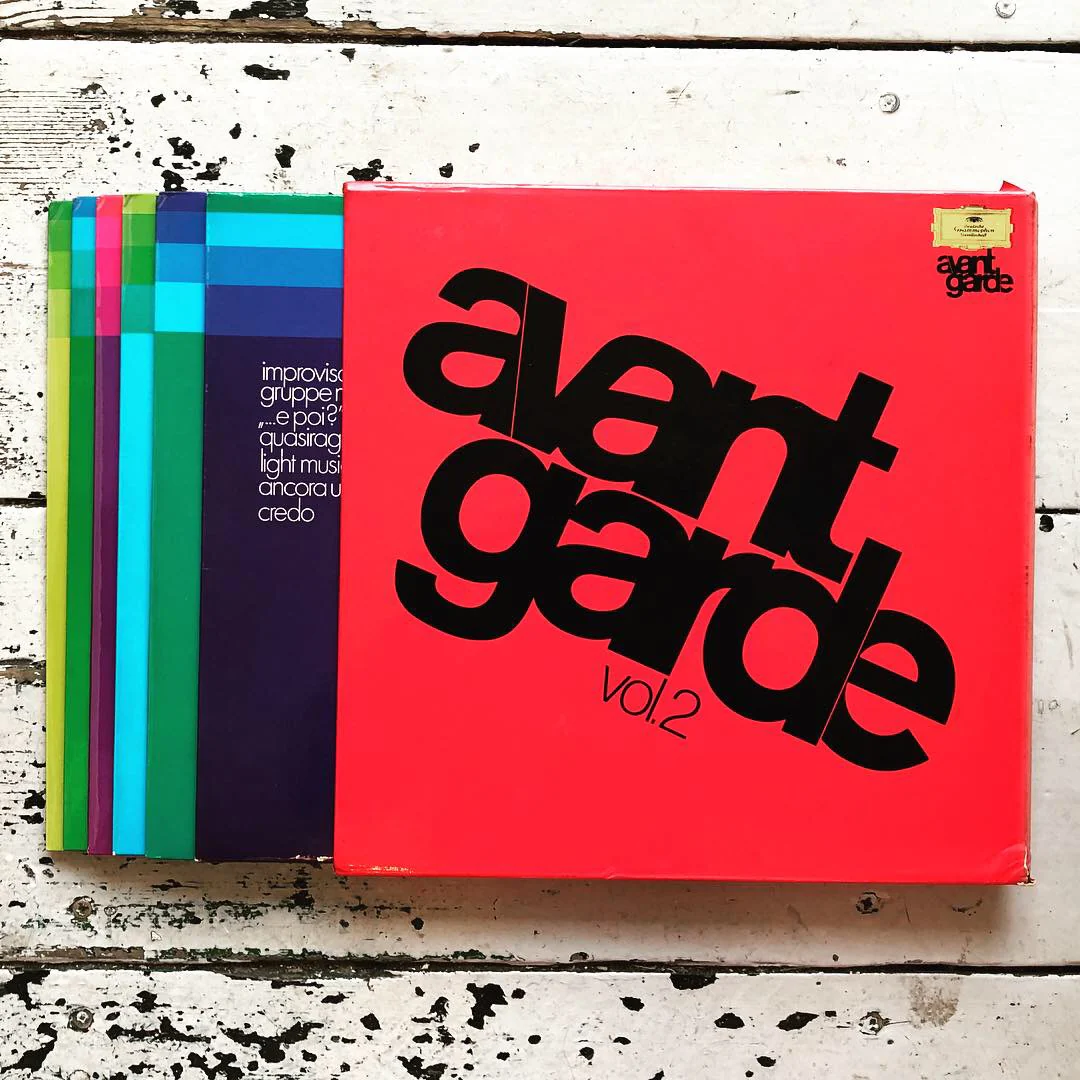

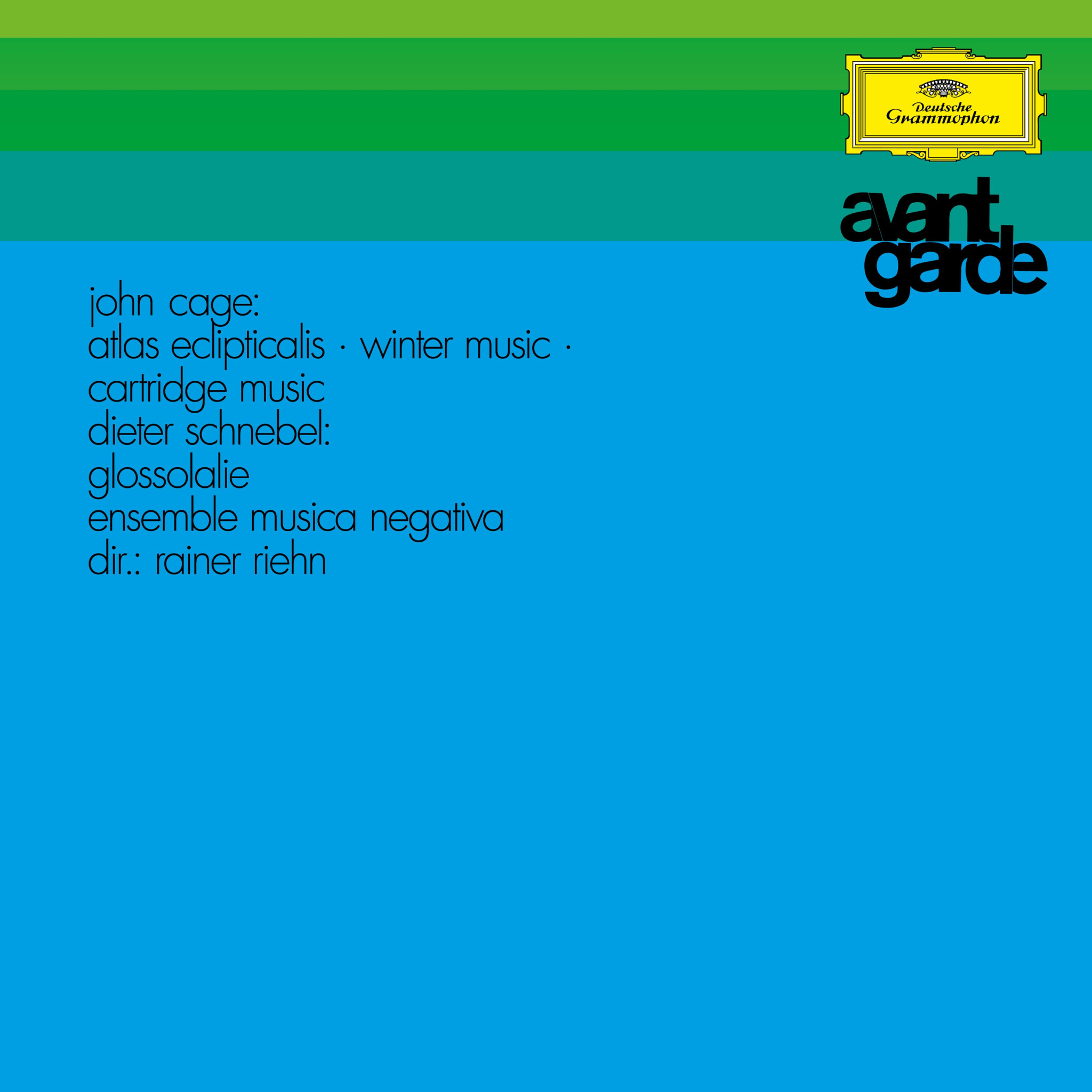

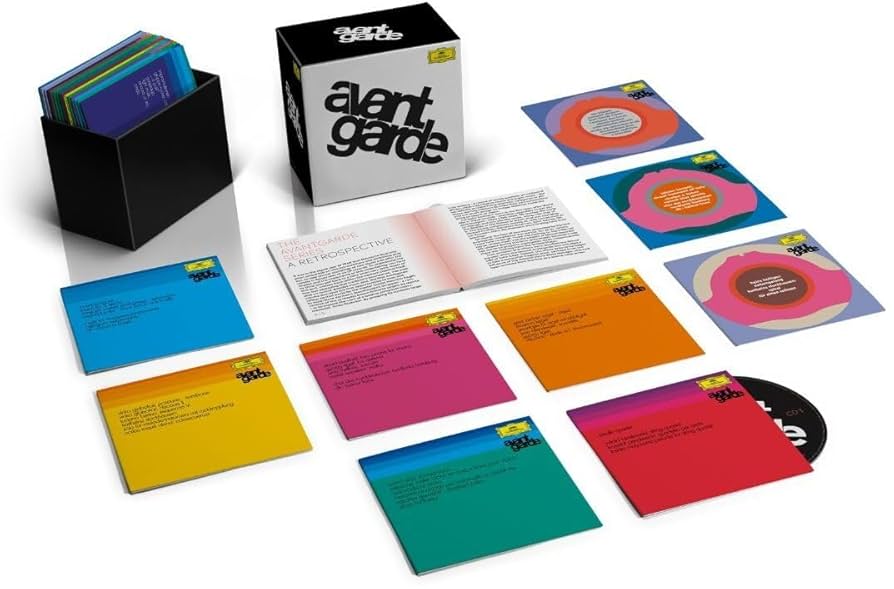

Then DG launched its iconic Avant-Garde Series of box sets dedicated to the hardcore modernists (some of whom will be forgotten names these days). These were presented in beautifully designed slip cases, tailor made for display on vinyl lovers’ walls.

Individual releases from these sets followed.

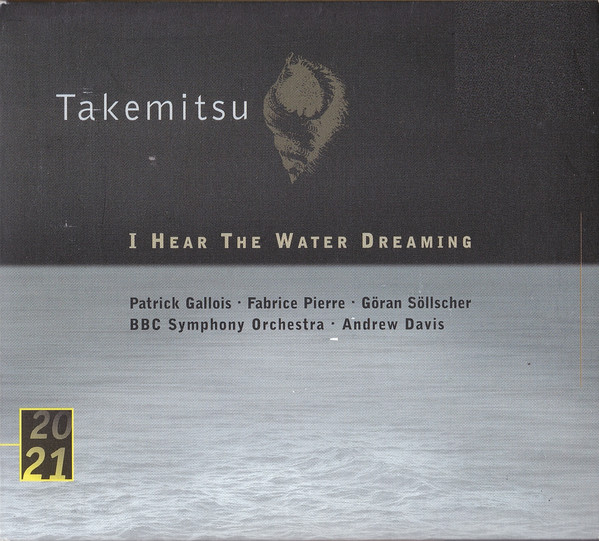

The series focused mainly on European composers, with nods to John Cage and Toru Takemitsu, who also received his own iconic Japan-only records featuring drop-dead gorgeous artwork and packaging. I'm a huge fan of Takemitsu and own several of these.

In the 2000s, DG revived its series of recordings of modern music on CD, with the banner title of 20/21 - Music of Our Time; the series is full of treasures, not least several outstanding Takemitsu releases.

A few years ago DG re-released its Avant-Garde series of recordings, minus the Stockhausen works (whose rights had reverted to the Stockhausen estate), in a desirable CD box; might we eventually see an Original Source reissue of one or two records from this series?

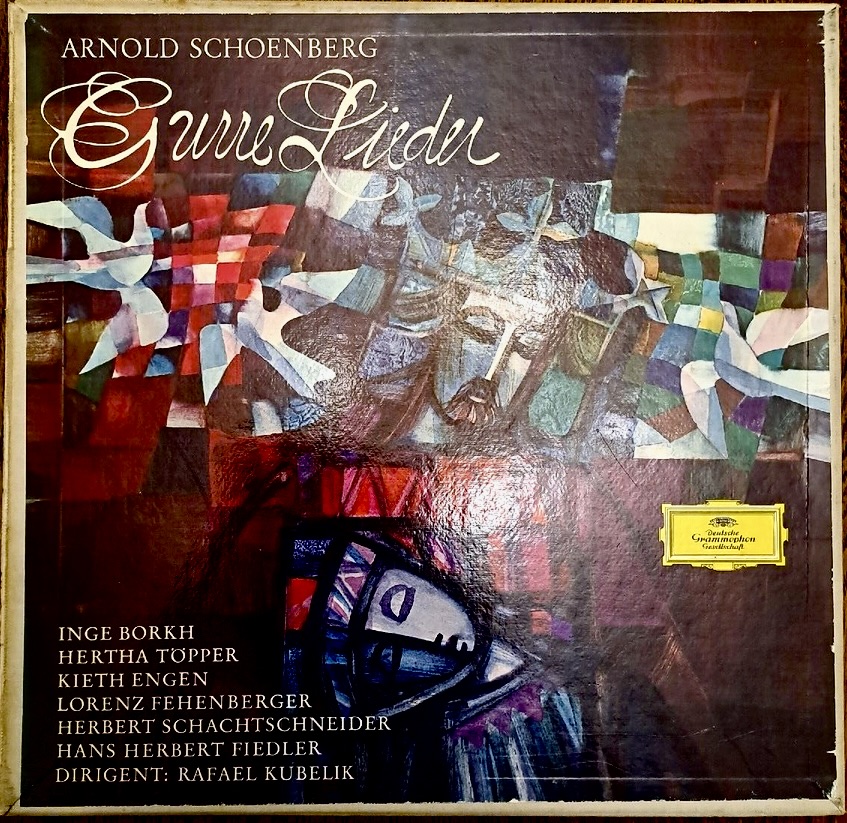

But, surprisingly, even at this late stage in the game in the early 1970s, the foundational music of Schoenberg, Berg and Webern had received short shrift from the Yellow Label prior to the release of Karajan’s survey. Rafael Kubelik had done the massive oratorio Gurrelieder in not entirely convincing fashion in 1965.

In this work the young Arnold was still working in a late-Romantic tonal idiom, intent on out-Mahlering even Gustav in the number of players, instruments, singers and soloists he could cram onstage. (He had special 48-stave manuscript paper made for him as he composed this monster).

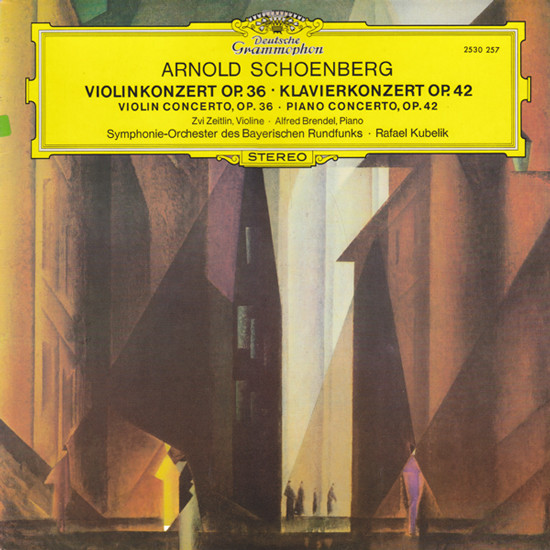

There had been an album of Schoenberg’s later, fully serial Violin and Piano Concertos in 1971, again with Kubelik at the helm (and Alfred Brendel tickling the ivories).

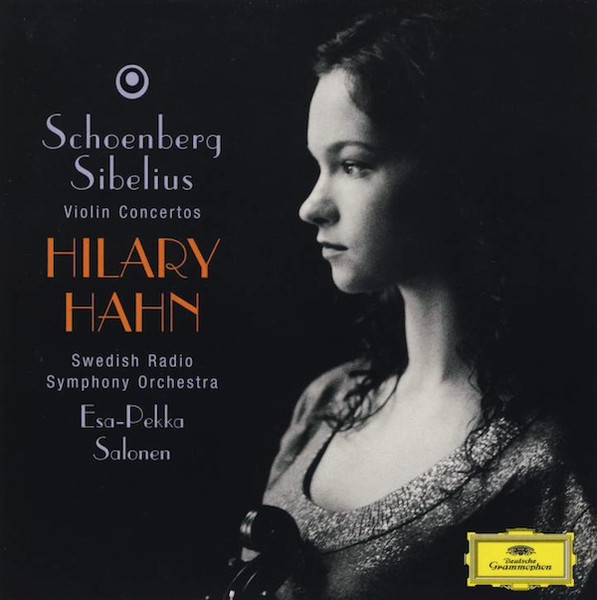

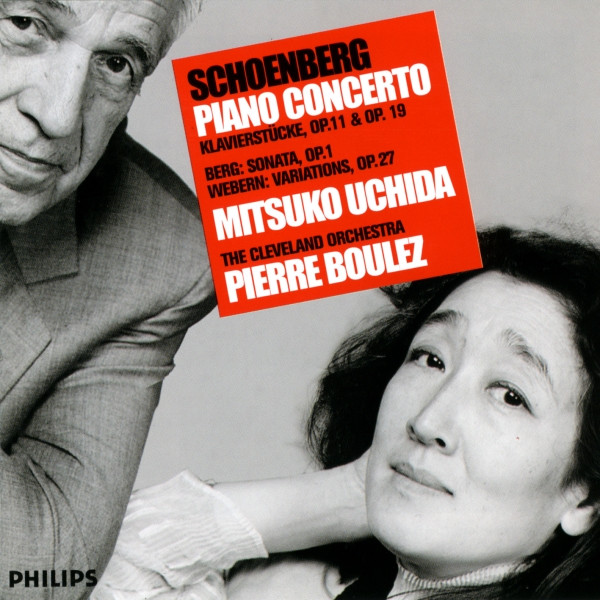

For more recent and, I think, more persuasive, recordings I strongly recommend Mitsuko Uchida in the Piano Concerto on Philips with Boulez conducting, and Hilary Hahn changing the game in the Violin Concerto (partnered by modern music expert Esa-Pekka Salonen). Hahn worked intensely on the piece for two years before programming it in concert and recording it, and she transforms it into something ravishing, romantic, and otherworldly to listen to.

In one of the more incongruent facts of musical history, the Piano Concerto was commissioned by one of Schoenberg’s Hollywood pupils, Oscar Levant, best known for his scene-stealing turns singing, dancing and playing show-tunes in An American in Paris and The Band Wagon! (Not someone you’d associate with the avant-garde by any stretch of the imagination).

Oscar Levant, who commissioned Schoenberg's Piano Concerto

Oscar Levant, who commissioned Schoenberg's Piano Concerto

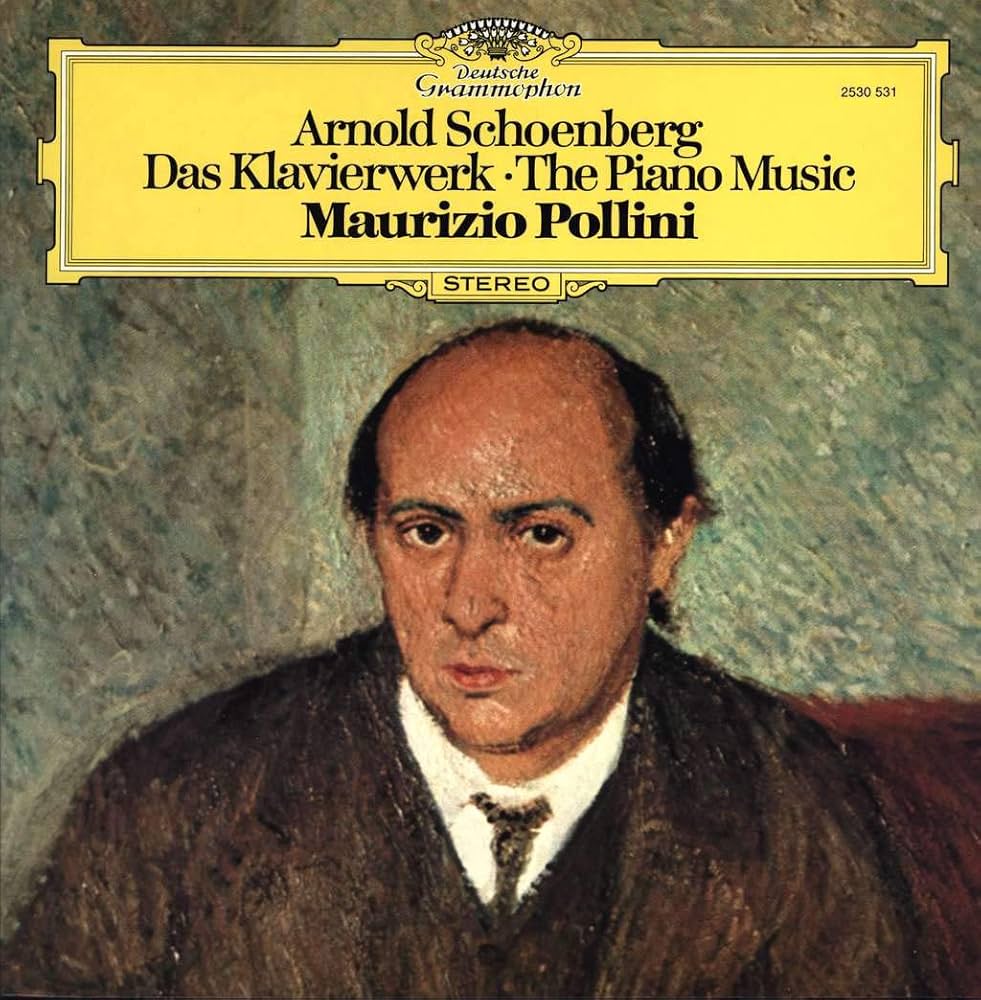

Maurizio Pollini’s game-changing DG release of Schoenberg’s piano music (another strong candidate for OSS reissue) wouldn’t emerge until 1975.

The most significant release of the output of the Second Viennese School on DG prior to Karajan’s set had been the 1971 box by the LaSalle Quartet of all the string quartets penned by Schoenberg, Berg and Webern, a set which remained unchallenged in performance and for completeness until comparatively recent times (pace the Juilliard Schoenberg recordings on Columbia).

(Schoenberg’s thorny string quartets recently received definitive, audiophile recordings on BIS on dual layer CD/SACDs with the jaw-droppingly assured Gringolts Quartet, led by the formidable Ilya Gringolts).

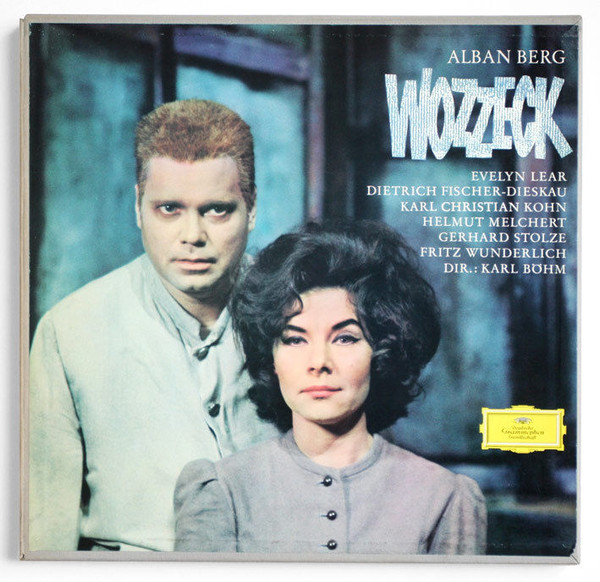

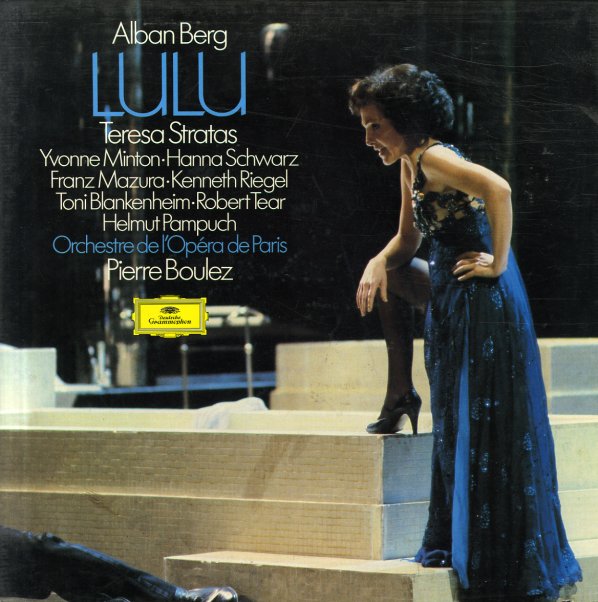

Berg’s two seminal operas, Wozzeck and the then incomplete Lulu, had both received benchmark recordings from Karl Böhm on DG in the 1960s. Lulu was later completed from Berg’s sketches by conductor and composer Friedrich Cerha in the 1970s, and enshrined in Boulez’s iconic recording for the Yellow Label.

Apart from the LaSalle set, I’m not even sure that any Webern had been released by DG prior to Karajan’s spellbinding single LP survey contained in this box. (In the CD era, Pierre Boulez remade his complete works survey that he had first tackled in a seminal set of recordings on CBS/Columbia in the 1970s).

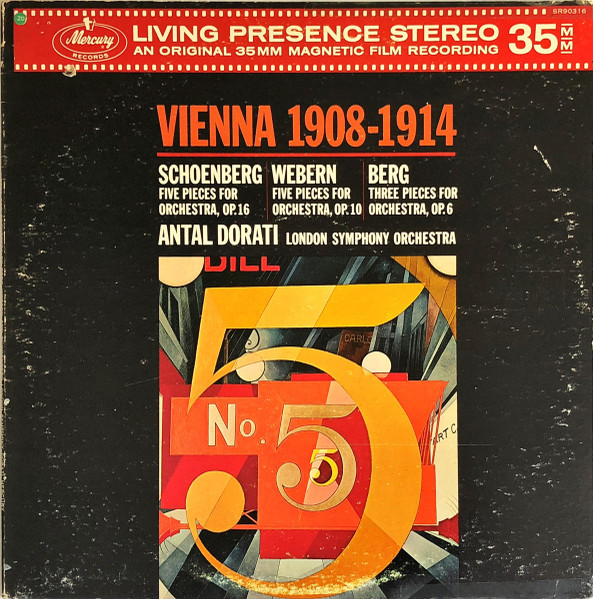

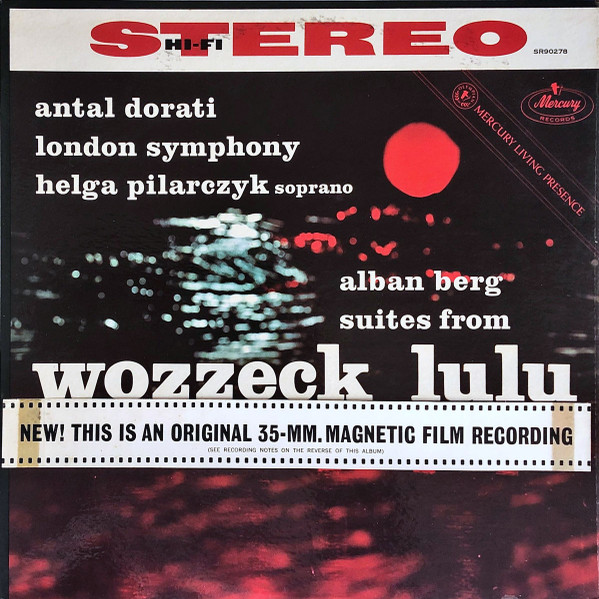

So, prior to 1974, apart from a few isolated, rare recordings of Schoenberg, Berg and Webern on smaller labels, plus Robert Craft’s records on CBS, there really hadn’t been anything like this Karajan set in the marketplace. The closest thing released in genuine audiophile sound were Antal Dorati’s two LPs recorded for Mercury Living Presence in 1961, comprising Scenes from Berg’s Wozzeck and Lulu, plus a Schoenberg/Berg/Webern compendium from 1964. It’s hard to find these in good shape at a reasonable price, so go for the excellent Speaker’s Corner slipcased threefer (or the individual releases). It’s an essential purchase for lovers of this music, offering a radically different take to Karajan - less overtly romantic, more analytical and “deconstructed” as it were.

I also really like James Levine’s single digital LP/CD on DG from 1987, also with the Berlin Phil; the Funeral March from the Webern 6 Orchestral Pieces is hair raising and quite different from Karajan’s rendition.

Claudio Abbado’s series of Berg releases on DG, starting in 1971, are well worth picking up too - his digital Wozzeck from 1988 is definitive (available on LP and CD). If you are into this music, you are really into it, and will want to grab everything out there!

Sightings of this music in concert halls were even rarer in the years leading up to the Karajan release. In the UK the BBC would program this stuff both on the radio and at the Proms (a huge 2-month festival of daily concerts centered at the Royal Albert Hall). I found that Henry Wood - the founder of the Proms - had conducted the first UK performance of the Passacaglia (which opens Karajan’s Webern selection) in 1931; Wood conducted the world premiere of Schoenberg’s important Five Orchestral Pieces at the Proms in 1912; and Berg’s Three Fragments from Wozzeck in 1934. The Schoenberg Piano Concerto gets its first UK performance in 1945, the Berg Violin Concerto gets its Proms premiere in 1955. Thereafter works from the Second Viennese School don’t start to be programmed - sporadically - until the 1960s.

To this day, if an orchestra programs Schoenberg and Webern in particular, especially in the second half of a concert, half of the audience is going to leave. (Living in LA during the Esa Pekka Salonen years, I was lucky to experience much rarely performed Schoenberg in concert, including his one-of-a-kind opera Moses und Aaron).

This is all testament to just how much resistance there was to this music - still - even by the time of the early 1970s. You were more likely to find records of Stockhausen, Boulez, Ligeti and their ilk in the bins than music of the Second Viennese School.

Which is a damn shame, because this music is so singular - and kinda mind-blowing! It is perhaps more accessible now than it was in the early 1970s because so much music has flowed under the bridge since then. And - surprise, surprise - Herbert von Karajan - in many ways the most traditional of German maestros (and considered by many to be the most superficial) and the Berliners prove to be supreme proselytizers on behalf of Schoenberg & co. They really dig deep into this music, and the results - even on the original release - were a game-changer.

Herbert von Karajan

Herbert von Karajan

When Herbert von Karajan, Deutsche Grammophon’s biggest star, and classical music’s golden goose, first told the label of his plans to record a four LP set of some of the most unpopular music ever written, they - not surprisingly - balked. This was simply too much of a hot potato for the bean counters who felt that even Karajan and the BPO’s star status wouldn’t sell records of music which was largely ostracized by the classical crowd. So Karajan put up the majority of the financing himself - and then laughed all the way to the bank! He liked to say that if you stacked up the number of LP and cassette copies of this box set that sold in its initial run, the pile would reach the top of the Eiffel Tower. It was a HUGE bestseller.

Go figure!

I think it was Karajan’s very obsession with the great German classical tradition which allowed him to find a through line in this music, that enabled him to connect it with listeners in a way that had eluded other interpreters before him, and often still eludes them now. Without playing down the music’s revolutionary aspects, Karajan brought out what connected these works to the past, and that helped listeners find the connection to their own experience with earlier, more traditional tonal music. Also it didn’t hurt that the playing was effortlessly virtuosic, with a beauty of sound unmatched in any recordings I’ve heard of these works before or since - now fully revealed in all their glory in this Original Source reissue.

In this new version, sonically enhanced in spectacular fashion by the team at Emil Berliner Studios - Rainer Maillard and Sidney C. Meyer - remixing and mastering from the 4 and 8 track master tapes directly to the cutting lathe, the makeover takes things to a whole new level.

... continued in Part 3...

In the upcoming Part 3, I talk about Karajan’s history with the Second Viennese School, and his distinctive and fastidious approach to preparing and recording these works. That is followed by a detailed examination and review of each record in the set, plus some suggestions for further listening and reading.

In Part 1 of this series of articles, I dive into the history and theory behind Schoenberg’s move into atonality and his creation of the 12-tone method, and how his work and that of his pupils Alban Berg and Anton Webern - the Second Viennese School - radically changed music at the dawn of the 20th century.

For this article I was naturally reliant on my own experience and knowledge of the records that have crossed my path over the years. But in a specialized area of the repertoire and catalogue like this it’s easy to miss things, so I invite anyone who can supplement what I have outlined above with their own experiences with records of this repertoire to do so in the comments section below. (Focus on primarily the period prior to 1974 - I will be covering some later recordings in Part 3). I’d love to hear from you!

Available at Acousticsounds.com

.png)