The Original Source Does Mahler on Steroids

Herbert von Karajan and the BPO Conquer All in this stunning Recording, one of the conductor’s very best

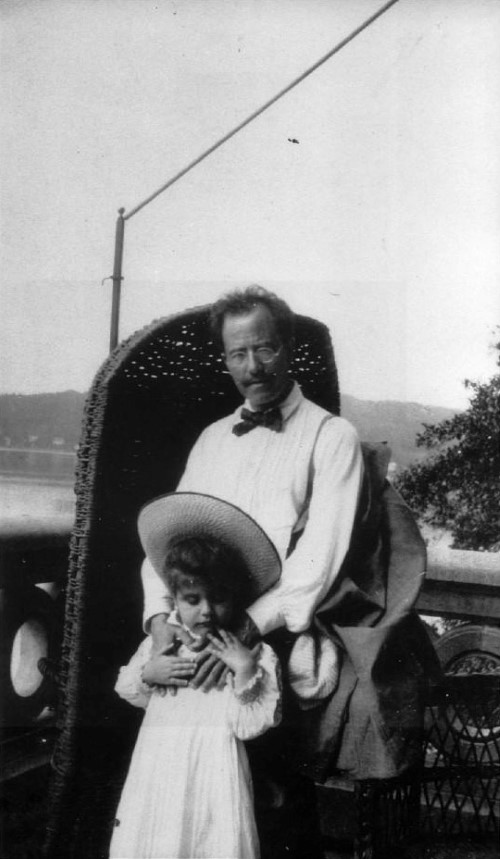

Gustav Mahler (photographed in 1907 by Moritz Nähr at the end of his tenure as director of the Vienna Opera)

Gustav Mahler (photographed in 1907 by Moritz Nähr at the end of his tenure as director of the Vienna Opera)

The past and present wilt—I have fill'd them, emptied them.

And proceed to fill my next fold of the future.Listener up there! what have you to confide to me?

Look in my face while I snuff the sidle of evening,

(Talk honestly, no one else hears you, and I stay only a minute longer.)Do I contradict myself?

Very well then I contradict myself,

(I am large, I contain multitudes.)”

Walt Whitman (#51 from Song of Myself)

Like Walt Whitman, and indeed every human soul, each Mahler symphony is a world unto itself, large and containing multitudes. Each symphony tells a profoundly humanistic story of life’s struggles - with fear and hope, love and loss, death and anxiety about what may come thereafter - while also celebrating the worlds of nature and beyond. It is the eternal struggle to find meaning in chaos. I think it’s the reason these works have become so popular in our age of modernism, technology, the death of faith. Mahler’s music is a vivid self-portrait of him grappling to find meaning in a world he finds ever more confusing and alienating, even as he clings to the possibility of beauty, grace, love and redemption.

Nowhere is this struggle more acutely portrayed than in the 6th Symphony, a work of coruscating passion, despair and - ultimately - nihilism. As the composer himself put it:

"It is the hero, on whom falls three blows of fate, the last of which fells him as a tree is felled."

In this work, to which the composer eventually gave the subtitle “Tragic”, there is no trace of the “Resurrection” that transfigured his hero at the end of the 2nd Symphony. As his friend and early champion, the conductor Bruno Walter, put it:

“...the Sixth is bleakly pessimistic: it reeks of the bitter cup of human life. In contrast with the Fifth, it says ‘No,” above all in its last movement, where something resembling the inexorable strife of ‘all against all’ is translated into music. The mounting tension and climaxes of the last movement resemble, in their grim power, the mountainous waves of a sea that will overwhelm and destroy the ship; the work ends in hopelessness and the dark night of the soul. Non-placet is his verdict on this world; the ‘other world’ is not glimpsed for a moment.”

Mahler (l.) and Bruno Walter in Prague, 1908

Mahler (l.) and Bruno Walter in Prague, 1908

And yet, for all its nihilism, I find this to be one of the most invigorating, most compelling, most life-affirming of all Mahler’s symphonic utterances. The struggle is all. A good performance will put you through the ringer, for sure; but a great performance will scramble your guts, claw at your soul, and force you on a journey that encompasses your entire life and consciousness. Though it will fell you mightily with those final hammer blows (more on these later), its implicit challenge will be to pull yourself out of the rank pit of despair and fight once more.

“Rage, rage against the dying of the light!”

I think this record captures one such performance, and in its new Original Source incarnation, Karajan and the Berliners’ scorching rendition emerges even more fiercely to challenge Dark Fate to do Its worst.

Bring it on!

The irony of all this is that the symphony was written during an especially happy period of Mahler’s life. Recently married to Alma Schindler, with one young daughter the composer doted on, and another on the way, the composer was also at the height of his success as a conductor at the Vienna Opera.

The Mahler House at Maiernigg

The Mahler House at Maiernigg

Yet in 1903, during his habitual summer break at Maiernigg dedicated to composition, in the idyllic surroundings of the Austrian mountains, he began to write a work which, while representing in many ways a summation of the five symphonies that had preceded it, displayed a pessimistic hue. In addition to the work’s struggle with existential dread, was this perhaps also a “putting to rest” of his compositional journey thus far so that he could move forward unencumbered? There is definitely a sense at the end of the work of having laid waste to all that has gone before.

Mahler's Composing Cottage at Maiernigg

Mahler's Composing Cottage at Maiernigg

The work unfurls as an intense psychodrama, depicting a “hero” caught between forces of destruction and Fate that would drag him down, yet also consumed by passionate love and aspirations of transcendence. The hero desperately fights for something beyond a mere act of survival.

The symphony is cast in four movements, though the order in which they are played remains a source of contention. The opening Allegro is a relentless march, eerily prophetic of military jackboots. Karajan and the BPO launch into it with ghoulish double-basses, a relentless forward motion that conveys a sense of the orchestra being untethered. The strings both bite and soar. Listen out for the beautifully textured tam-tam and the snarling xylophone, just part of a rich, constantly shifting orchestral landscape. A "March into Hell" with stunning vistas.

All of this is contrasted by the second subject, a soaring lyrical melody that recurs throughout the whole work, representing the composer’s wife, Alma, who recalled: “After [Gustav] had drafted the first movement, he came… to tell me he had tried to express me in a theme. ‘Whether I’ve succeeded I don’t know; but you’ll have to put up with it.’”

Alma and Gustav in 1909

Alma and Gustav in 1909

The almost demonic Scherzo - all fragmentation and dissolution - was originally placed second in the first published edition, but during rehearsals for the first performance in 1906 Mahler moved the slow Andante to that position, placing the Scherzo third, where it remained in later editions. The order in which these movements should be performed remains unsettled, and different conductors do it differently. Leaving the Scherzo second emphasizes the radical way in which the symphony disrupts normal custom (and if nothing else this is a profoundly disruptive work). It also accentuates the sense that the Scherzo acts as a hair-raising “dark universe” reflection of the first movement.

Listen out for the intricate string work, with sonically vivid col legno (when players use the wooden side of the bow to hit the strings). The demonic progress degenerates into a demented tango. Timpani hits in the Original Source mastering have depth and texture; tam-tam, bass and brass growl like Fafner awakening to face young Siegfried - but in this world of the Upside-Down the dragon will slay the Hero. A thrilling solo trumpet rings out clear and true, unrestrained in any way by the mediation of recording technology. As the movement limps towards its conclusion there is a sense that we have heard the orchestra being dismantled piece by piece, until all that's left is a halting low bass - then silence.

This world does indeed end with a whimper, not a bang.

Then the third movement Andante acts as a much needed respite before the epic journey of the Finale.

This is the movement order that Karajan follows, and it is certainly the order I prefer.

After the nihilism of the first two movements, replete with ghastly pre-echoes of the war that would consume Europe within a few years of the composer’s death in 1911, the Andante appears like a slow blooming Spring flower in a high Alpine pasture, pushing its buds through the melting slow. Here the Berliners' high violins float both effortlessly and intensely. The glistening silver strains of the celeste, far from the Nutcracker's Kingdom of Sweets, fall like dew. It is one of Mahler’s most sublime creations, less obviously effulgent than the slow movements of the 3rd and 5th Symphonies, but it builds inexorably to a climax (with a radical, heart-stopping key-change) that never fails to bring a lump to my throat, tears to my eyes: a musical depiction of Alpine meadows in full colorful bloom after the wastes of Winter. You’ll know it when you hear it.

Even the minutely imperfect tuning of the final chords is irrelevant. Karajan was famous for letting less than perfect takes stand if the music was right. Let it also be noted that he was famous for recording in much longer takes than other conductors, lending a "live" quality to the sessions - a factor much in evidence here.

At this point it is necessary to remind oneself of Alma Mahler’s words:

“The Sixth is the most completely personal of his works, and a prophetic one also. On him too felled three blows of Fate, and the last felled him. But at the time he was serene; he was conscious of the greatness of his work. He was a tree in full leaf and flower.”

Mahler with his daughter Maria at Maiernigg in 1905 She would die a short two years later.

Mahler with his daughter Maria at Maiernigg in 1905 She would die a short two years later.

That moment of serenity at the end of the third movement is the point from which the huge last movement begins its tortured journey. A low pizzicato in the strings, a cascade from harps and celeste, announce a soaring string line grasping at the heavens that is cut down by a massive major chord in the wind and brass that then turns to the minor, - victory turning to defeat - accompanied by the march rhythms from the first movement in the timpani. The string line collapses downwards, ending up by disintegrating into the halting ‘cellos and basses. Karajan’s way with this is unmatched, at a perfect tempo, with the rich Berlin strings conveying rapt intensity.

That motto of major turning to minor recurs many times as the movement charts a series of monumental efforts to build the necessary strength and determination to overcome the crushing heel of Fate. The sheer orchestral virtuosity on show here is breathtaking, as the hero and his music gathers themselevs over and over again to try and overcome their destiny.

But then three times during the course of the movement come a series of massive hammer-blows that strike down the “hero” just as he is within sight of his goal. For this, orchestras have to own or build a special wooden apparatus - literally a wooden hammer and resonant chamber to bring it down upon. The BPO built such a device for this recording and its associated live performances, and I should warn you the sound is so percussive and massive that at higher volumes your speakers might be in danger. (As is generally the custom - dictated by Mahler himself - the third “hammer blow of Fate” is conveyed by drums and regular percussion only, indicative of the level of exhaustion in the “hero” at this point; Leonard Bernstein, however, in his DG recording, reinstates the hammer itself).

The Berlin Philharmonic's "Hammer", about to be used in a performance conducted by Simon Rattle

The Berlin Philharmonic's "Hammer", about to be used in a performance conducted by Simon Rattle

As Alma Mahler described, her husband would indeed be felled by three hammer blows himself within a year of premiering this symphony: the death of his four-year-old daughter Maria, his departure on unfriendly terms from his post at the Vienna Opera, and a diagnosis of the heart condition which would kill him within five years.

-taken-by-carl-julius-rudolf-moll-(1861-1945).-.jpeg) Mahler's Death Mask, made in 1911 by Rudolf Moll

Mahler's Death Mask, made in 1911 by Rudolf Moll

What is it that makes Mahler’s music so unique? Insight is to be gleaned from these remarks by the great 20th century American composer, Aaron Copland:

“It is music that is full of human frailties ... so ‘Mahler-like’ in every detail. His symphonies are suffused with personality – he has his own way of doing and saying everything. The irascible scherzos, the heaven-storming calls in the brass, the special quality of his communings with nature, the gentle melancholy of a transitional passage, the gargantuan Ländler, the pages of an incredible loneliness... Two facets of his musicianship were years in advance of their time. One is the curiously contrapuntal fabric of the musical texture; the other more obvious, his strikingly original instrumentation…

“It was because Mahler worked primarily with a maze of separate strands independent of all chordal underpinning that his instrumentation possesses that sharply etched and clarified sonority that may be heard again and again in the music of later composers. Mahler’s was the first orchestra to play ‘without pedal,’ to borrow a phrase from piano technique. The use of the orchestra as many-voiced body in this particular way was typical of the age of Bach and Handel. Thus, as far as orchestral practice is concerned, Mahler bridges the gap between the composers of the early 18th century and the Neoclassicists of our own time.”

KARAJAN AND MAHLER

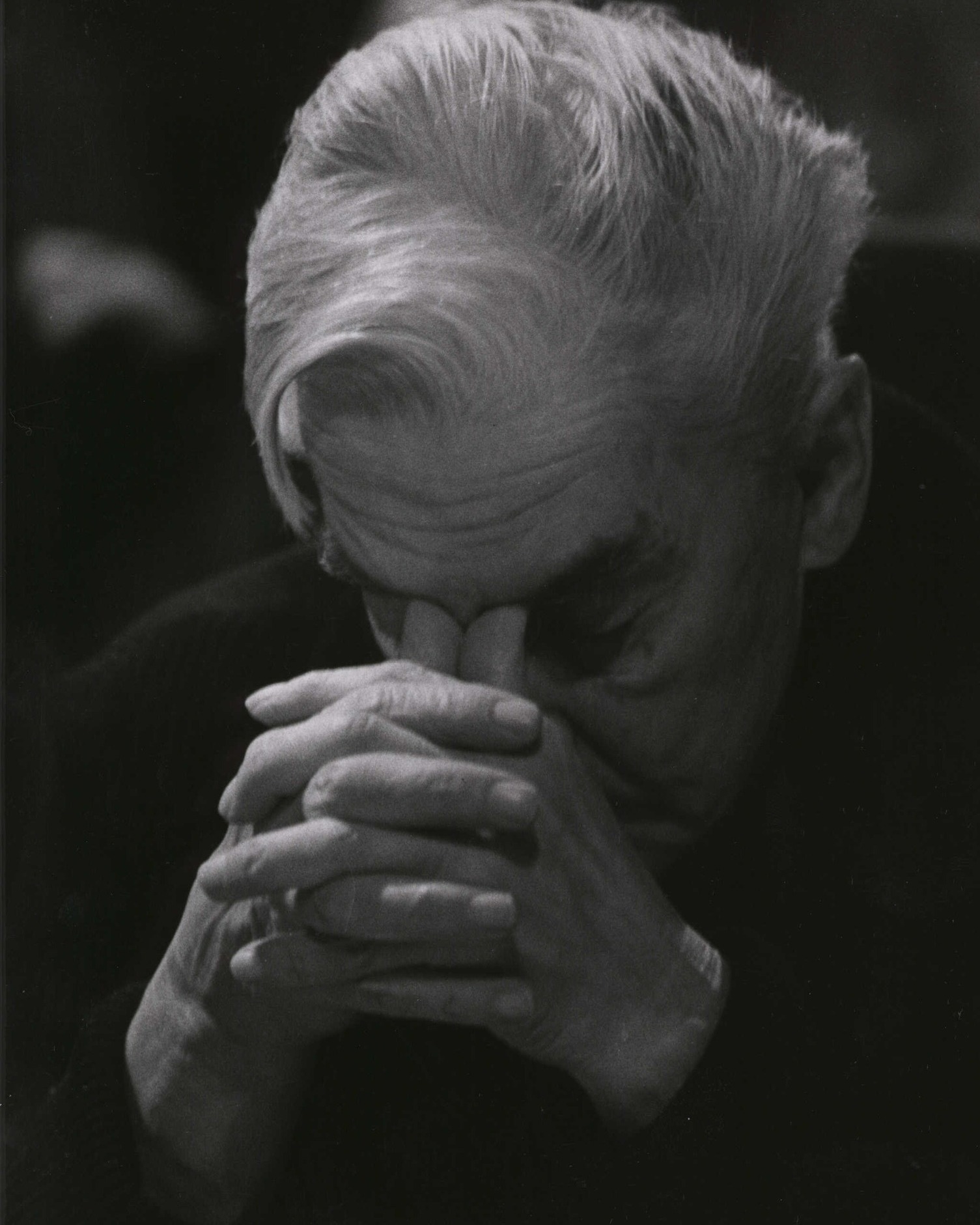

Herbert von Karajan

Herbert von Karajan

Herbert von Karajan turned to the 6th Symphony in the mid-1970s, at a time when he himself was struggling with serious back problems that almost killed him. The conductor - then at the height of his powers and flourishing as Principal Conductor for Life of the Berlin Philharmonic - had turned to Mahler relatively late in his career, maybe in part to respond to the sudden ravenous public appetite for his music from the record-buying public. (Karajan was never one to miss a commercial opportunity).

His early recordings of Mahler - spear-headed by his account of the 5th Symphony, one of the first Original Source releases - were, both in terms of performance and recordings, a mixed-bag. Not so this 6th, recorded a few years later. From the moment it was released it was hailed as something very special indeed.

In his essential biography of the conductor (as insightful a study of what a conductor actually does as any), Richard Osborne makes the valid connection between the symphony’s aura of doom and the health adversities Karajan was facing at the time, as well as his own personal memories from childhood of the impending outbreak of World War I. Osborne is so eloquent on all this, I will make no attempt to paraphrase, and instead will quote in full:

“…the symphony as a whole touched him profoundly at several levels. With its marching and counter-marching, its major triad souring on the instant into the minor, it is a work that predicts war: that strange, unsettling word the young Heribert von Karajan heard his uncle mention that fateful day in July 1914 as the funeral convoy of the assassinated Archduke passed by the island of Brioni. Ezra Pound once said that a great artist is like the member of the tribe who smells the forest fire long before anyone else…

“And there is more. It is a symphony in which the hero is struck down by three hammer-blows of fate. It depicts married love, and its obverse: isolation and total solitude. The first movement development section is remote mountain music. Schoenberg marveled at the scoring here, its icy purity and the quiet clunk and jostle of cowbells, the last terrestrial sound, said Mahler, to penetrate the solitude of the mountain peaks.

“There can be little wonder that Karajan felt drawn to all this. What is surprising is that he did not feel threatened by it. He was a superstitious man with a weakness for astrology. Having been struck by one hammer-blow (the life-threatening spinal condition), he was about to be struck by a second. But the music drove him on. In the months before the recording in September 1977, he conducted the symphony in Berlin, Salzburg, London [I tried unsuccessfully to get tickets - MW], Paris and Lucerne. The following year he included it at the Salzburg Whitsun Festival, after which would come more serious illness. By rights that should have been that; but he went back to the work, in Tokyo in 1979 and in Berlin in the autumn of 1982 when, astonishingly, he conducted the Sixth and the Ninth symphonies within days of one another.”

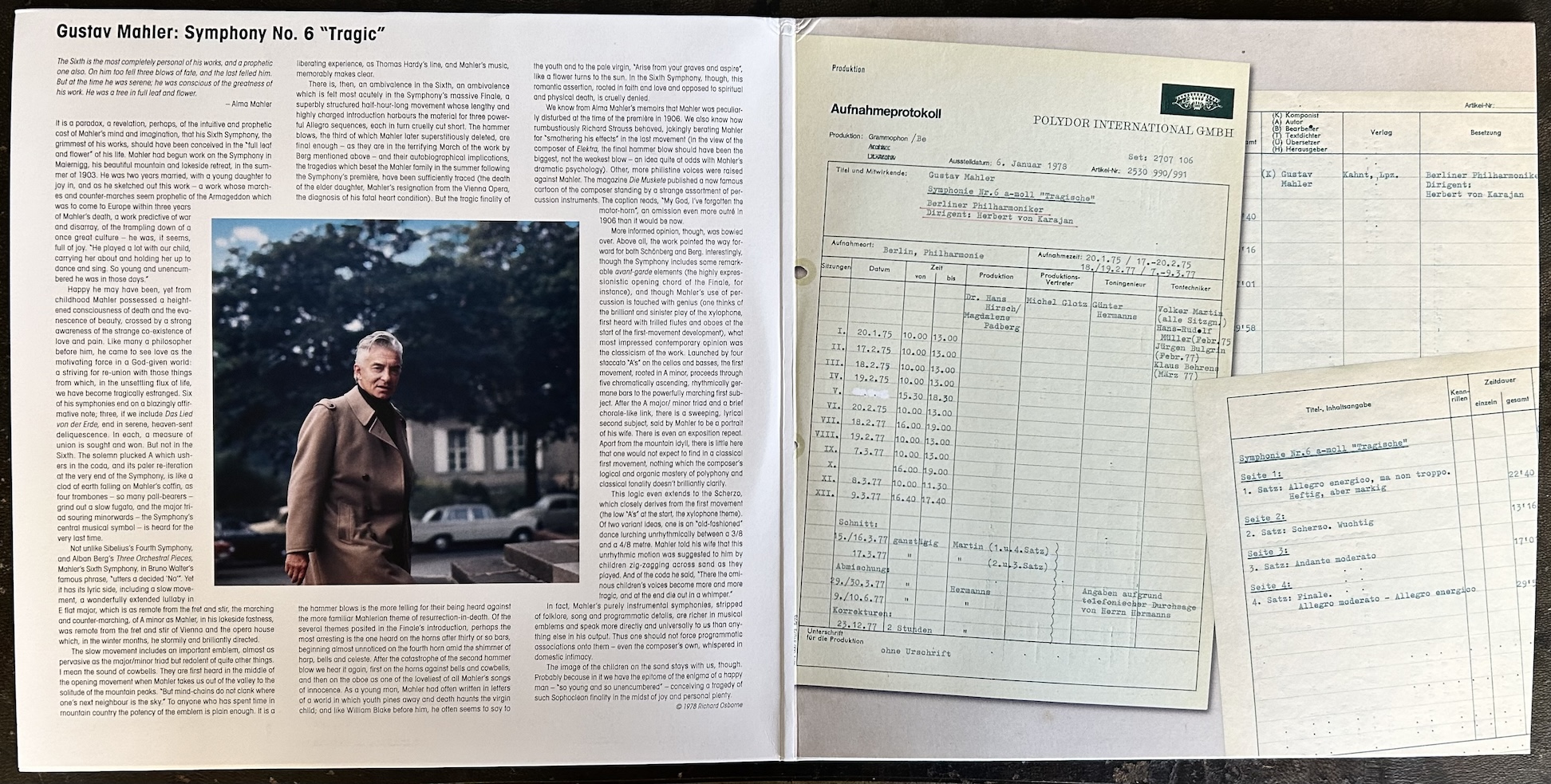

Included with this Original Source reissue is Richard Osborne’s original accompanying sleeve-notes on the symphony itself, an essay which I could have easily quoted in full and left it at that. It’s as eloquent an illumination of the 6th Symphony as any you are likely to read anywhere.

Gatefold of Original Source Reissue

Gatefold of Original Source Reissue

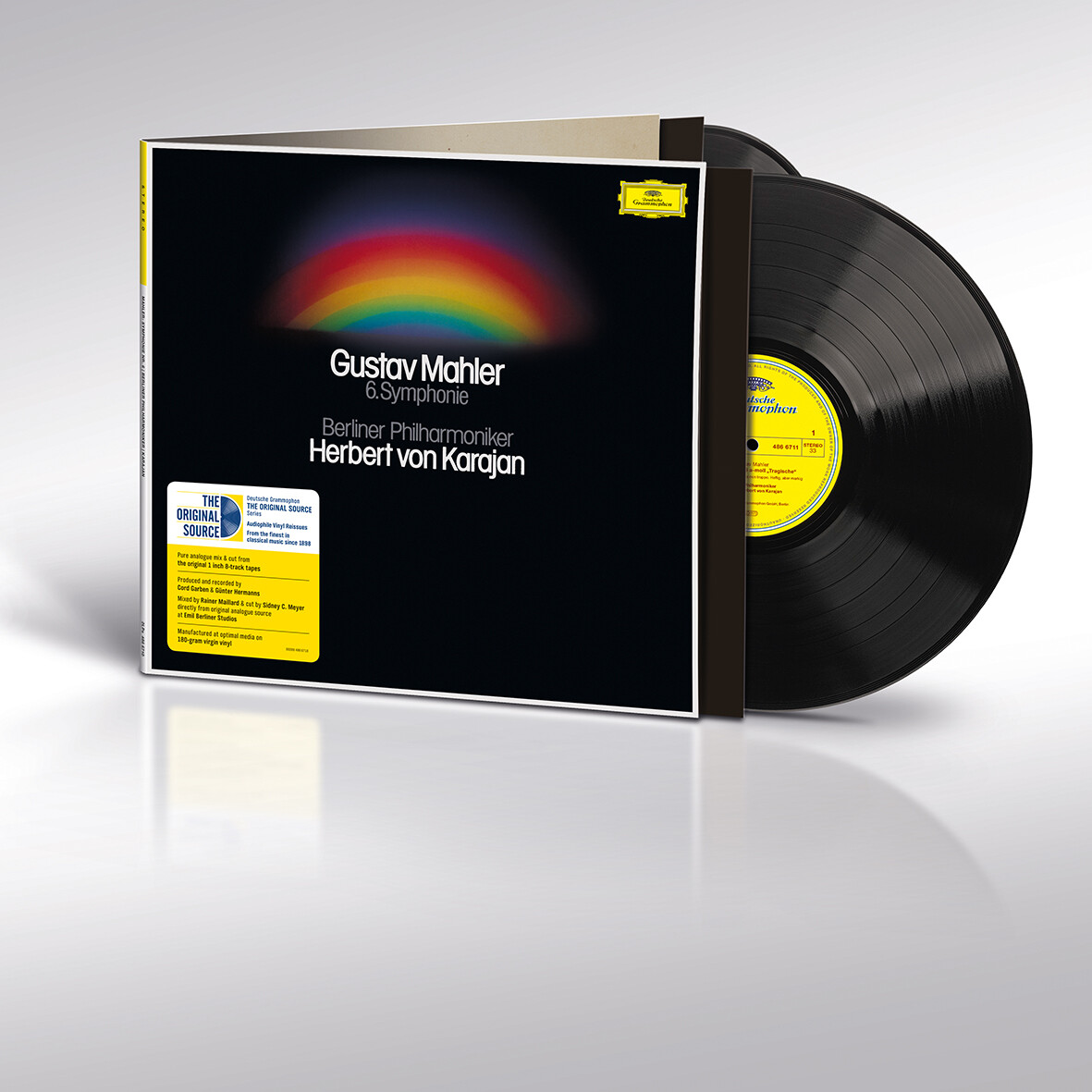

Karajan’s profound insight into, and identification with, this work is evident in every second of this recording, and the Berliners play their hearts out for him. Recorded in the Berlin Philharmonie, the original LP release was always one of the better-sounding DG records of the era. This new Original Source version, mastered and cut as always directly from the original master tapes (in this case 8-track) by Rainer Maillard and Sidney C. Meyer at Emil Berliner Studios, takes things to a whole other level sonically. It is revelatory. (My pressing was immaculate).

Karajan outside the Philharmonie

Karajan outside the Philharmonie

As was evident in the Original Source reissue of Karajan’s complete Bruckner Symphony cycle, Maillard and Meyer have found the sweet spot for revitalizing the somewhat problematic acoustics of the Berlin Philharmonie of the 70s, which by the time of these sessions in 1977 had supplanted the Jesus-Christus Kirche as Karajan and DG’s recording venue of choice. By using a combination of folding in the usual two channels of room ambience recorded on the original master tapes (originally intended for a quadraphonic release that never happened), together with using the stairwell at Emil Berliner Studios as an echo chamber, Maillard has found the perfect blend of direct and reflected sound to make this huge orchestral canvas shine.

Rainer Maillard at Emil Berliner Studios mixing and mastering Mahler's 6th Symphony

Rainer Maillard at Emil Berliner Studios mixing and mastering Mahler's 6th Symphony

Mahler’s enormous orchestra is laid out before you in a massive three-dimensional space, deep and wide. The aural palette is the 3-strip Technicolor of Jack Cardiff's stunning cinematography in Black Narcissus and The Red Shoes - a slightly heightened reality, bright, assertive, a little more than lifelike in the manner of an Old Master who gives you both beauty and truth. You are getting a spectacular tour of all the amazing sounds an orchestra can make, with full dynamics. Let me just mention again that xylophone, which spits out its chattering skeletal volleys with special vehemence, prefiguring Berg’s use of the instrument in the similarly noir "March" in the Three Orchestral Pieces - another superlative Karajan recording which, I very much hope, will get the Original Source treatment along with the entire Second Viennese School box set, fingers-crossed.

Did I mention the cow bells and church bells that feature in the score? Normally these are accommodated in various usually unsatisfactory ways, but Karajan’s fondness for technology inspired a most elegant solution. Recording engineer Günter Hermanns and his team recorded actual cowbells and church bells on a separate tape, which was then piped into the live performances via loudspeakers in the hall. For this Original Source remastering, Maillard had to blend in these tracks running on a separate tape deck, together with all the other tape elements he was juggling. The end result is seamless, with completely realistic aural perspectives for these sounds, varied according to the different sections of the score they are featured in. The process by which this was all done is explained in this fascinating video.

This is the recording of Mahler’s 6th I imprinted on when I was a teenager. I own several other fine versions of this work on LP and CD: most notably Leonard Bernstein with the Vienna Philharmonic live on DG. It's a favorite for many, especially TA colleague Paul Seydor, and don't get me wrong, it's a fabulous performance. Alas it is early digital, but was beautifully remastered by the Emil Berliner team for a box set vinyl release of all of Bernstein's DG Mahler Symphonies a few years ago, and reviewed here by my colleague Michael Johnson (you can still find it).

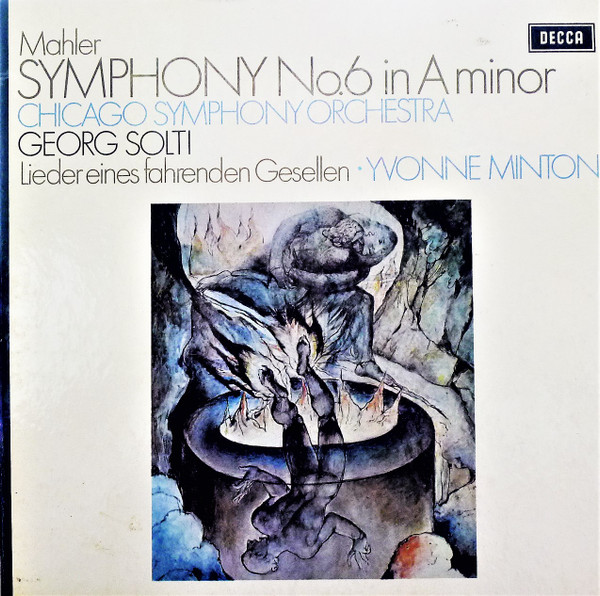

Georg Solti brings us a fiery version with the Chicago Symphony on a vivid sounding Decca pressing from the 1970s.

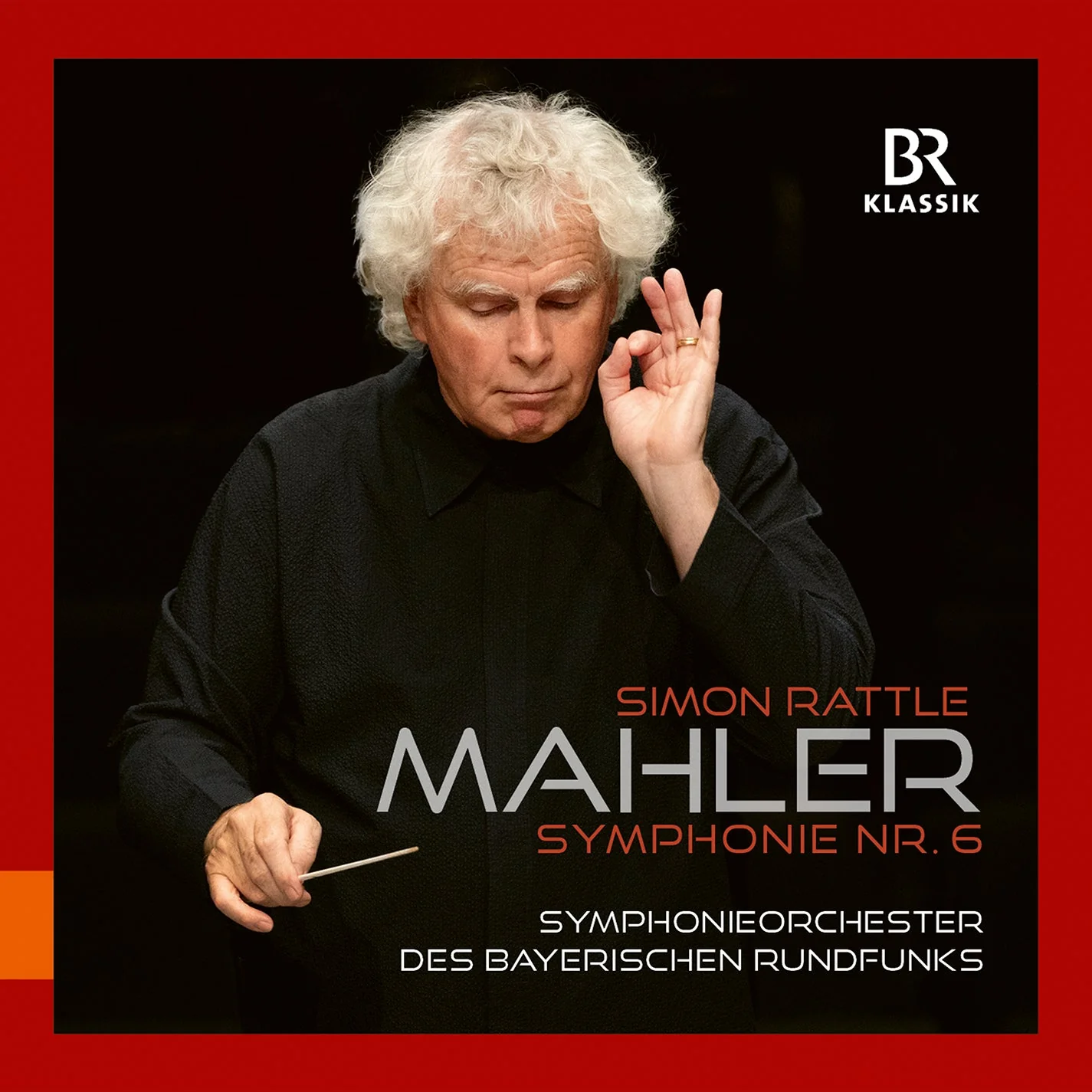

Tennstedt on EMI is highly regarded, and the symphony has become something of a Simon Rattle specialty - there are two performances released on the BPO’s in-house label. Paul Seydor speaks highly of Rattle’s most recent version with the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra (I've not heard it).

But this Karajan/BPO reading has always remained my preferred recording. In its new incarnation it is simply out-of-this-world stunning. Karajan and the Berliners are the ones with the extra adrenaline rush, the manic ferocity, the heart-rending sense of love and loss. This is Life itself.

One of the features that has emerged in the course of the Original Source series is that by mastering and cutting so faithfully from the original master tapes (with no intermediate stereo mix-down), and by folding in the information from the ambient tracks, we are able to hear every little detail in the recording techniques used in the original recordings - for better or worse. As I wrote in my review of the Original Source reissue of Karajan’s Mahler 5th, while the sonics were massively improved, I could hear even more clearly the ways in which the acoustics of the Jesus-Christis Kirche had impacted on the recording. Also I could hear how the engineering team seemed to have manipulated shifts in perspective (to bring out certain orchestral detail) in a manner that occasionally derailed the integrity of the sonic picture the recording was presenting.

There’s none of that here. This is such a vivid, truthful presentation of a huge orchestra playing at full tilt, yet with every tiny instrumental detail emerging organically, that I predict this set will become de rigueur for every High End audiophile dealer endeavoring to demonstrate what his or her equipment is capable of. Over and over again I was gasping at the power, precision and realism of what I was hearing. Sidney Meyer’s cutting fully accommodates the massive dynamic range, and the long side length of the fourth movement (clocking in at 29’58) holds no terrors for her. There is no trace of distortion, or sonic compromise to achieve that lack of distortion.

Sidney C. Meyer (Emil Berliner Studios)

Sidney C. Meyer (Emil Berliner Studios)

And let’s just also tip our hats here to the original recording team led by Günter Hermanns. This was always a very good sounding recording, but now it is revealed as maybe Hermanns’ engineering and sonic masterpiece.

Günter Hermanns

Günter Hermanns

This is a very different aural picture from what we are familiar with from the best RCA Living Stereos, Mercurys, Deccas and EMIs that capture large orchestras playing in a well-defined acoustical space. It’s simply on a larger scale in every dimension. It’s both massive and intimate - and that is quite a feat. It definitely stands shoulder-to-shoulder with all those audiophile classics.

In a work which is all about juxtapositions of the epic and the intimate, this is an ideal sonic presentation. The recording accommodates every dynamic and timbral extreme effortlessly. No lover of classical music should be without this record in their library, and DG should not even hesitate to go right ahead with a repress. This thing deserves to sell out immediately and then never be unavailable. In a line of many first-class releases in the Original Source Series, including personal favorites like the Ozawa Symphonie Fantastique, Pollini’s Chopin Preludes, Steinberg's Hindemith record, and the Karajan Bruckner cycle (go back and read all my and Michael Johnson’s reviews), this one stands at the pinnacle.

I can think of few records that come so close to fully capturing the live experience of hearing an orchestra of this scale and quality pushing the envelope. (Rainer Maillard’s D2D of the live BPO with Haitink doing Bruckner’s 7th is definitely in the same pantheon).

This release captures something really special: a moment in recording history, lightning in a bottle. It conveys to thrilling effect the full force of what made Karajan and the Berliners of this period unique and, in many ways, still unequalled. Hell, it might even convert the Karajan naysayers!

.png)