Decoding the Dawn of Modern Music - The Original Source Offers Fresh Illumination of Karajan and the BPO's Groundbreaking Survey of the Second Viennese School - PART 1

Breaking Classical Music (or: What Schoenberg Did)

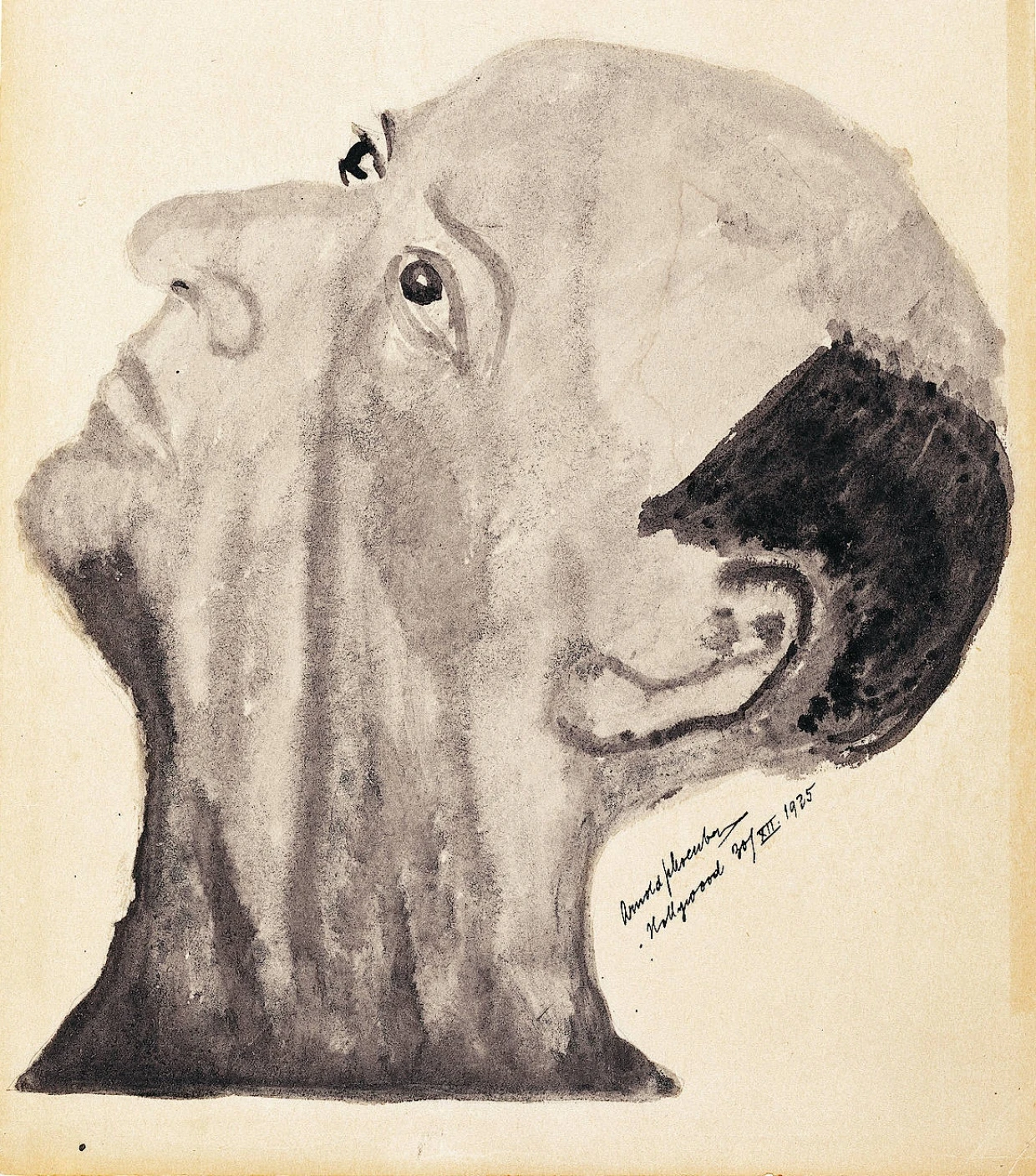

Arnold Schoenberg in 1937 in a suitably "meta" moment, with a bust of himself by Rudy Zack

Arnold Schoenberg in 1937 in a suitably "meta" moment, with a bust of himself by Rudy Zack

“Art is from the outset naturally not for the people”.

Arnold Schoenberg

“I, however, wish nothing more ardently, if I wish anything at all, than that people would look upon me as a better version of Tchaikovsky - a little better, for God’s sake, but that is really all I ask for. Or at most, that people would know and whistle my melodies.”

(also) Arnold Schoenberg

The “problem” with the music of Arnold Schoenberg - and the whole panoply of atonal, serial and avant-garde classical music that followed in its wake over the course of the 20th century - is encapsulated in those two quotes from the composer.

Leaving aside the question of whether the father of atonality and serialism was actually so clueless (or at least disingenuous) as to fully believe what he was saying in both cases, the two statements taken together flag the huge problem that would overtake classical music as it succumbed to the aesthetic convulsions - largely at the hands of Schoenberg and his two famous pupils - that overtook it in the wake of World War I, that momentous watershed that irrevocably changed every aspect of society, including the creative arts.

In a nutshell, classical music - by embracing the new musical language created by Schoenberg, Berg, Webern and their successors - lost its audience even as it believed it was reinventing and reinvigorating itself for a new century. (While Stravinsky, Bartok - even Richard Strauss in his opera Elektra - and others also introduced their own brands of modernism, no less “modern” or even revolutionary in their own ways, they never alienated their listeners to the same extent; nor did they create their own completely new compositional method). The adopters of Schoenberg’s methods felt they were prophets, visionaries, the Chosen Ones who would lead classical music into a Brave New World. Who cared if few wanted to actually listen to their music! Those who did engage with their work were the true listeners, the true appreciators of Great Art - the true believers and congregation for the music of the future.

Yet - I would argue - lurking beneath all that bombast (epitomized by the first quote at the head of this article) was a desire to be heard, a desire to be loved and admired. That desire is epitomized by the sentiments expressed in the second quote. I am more than skeptical of any artist who declares that he or she couldn’t care less whether their work is appreciated or not, let alone heard, read, or viewed. Really?! My suspicions are confirmed by Schoenberg’s almost guiltily expressed desire in the second quote: to be loved not just as much as, but even more than Tchaikovsky, the most commercial, tune-ridden composer there ever was. That Arnold Schoenberg - the most dogmatic, theorizing, unflinchingly modernist composer of his time (maybe of any time) - wanted to be hummed more than Tchaikovsky by the man in the street on the way to work…!

Was he delusional?

I think not.

Schoenberg in 1937 with three of his self-portraits

Schoenberg in 1937 with three of his self-portraits

But he certainly had his own way of looking at things! Which, of course, was why he doggedly pursued the path he did, even as it incurred open hostility from audiences, critics and other composers. Arnold Schoenberg’s obstinacy was, naturally, both his weakness and his strength, and was also wrapped up in his powerful sense of being both the inheritor of the Great German Tradition in classical music, and a Jew working in an environment of increasing hostility. That hostility would eventually lead him to emigrate to the US, and settle in Los Angeles, like Stravinsky and so many other European artists escaping persecution. There he taught at UCLA, lived in Brentwood with his second wife and young family, and by all accounts was very happy - a lifetime and half a world away from the struggles of his early life.

Schoenberg with his family at his home in Brentwood, Los Angeles, just down the street from OJ Simpson's former abode. The house still stands, occupied by his grandson, Ronald.

Schoenberg with his family at his home in Brentwood, Los Angeles, just down the street from OJ Simpson's former abode. The house still stands, occupied by his grandson, Ronald.

The dual impulses expressed by Schoenberg in those two quotes tell you a great deal about the man, his relationship to music (his own and others’), and the mantle of his legacy taken up by his two most famous pupils. Keep these quotes in mind as you listen to the music in this reissue.

So, given the fact that Schoenberg and his pupils, Alban Berg and Anton Webern, effectively burned down the House that Classical Music Built, and are stilled viewed with suspicion, if not downright hostility, by many, if not most, classical music lovers, what indeed are we to make of this deluxe AAA reissue of core masterpieces from each respective composer’s body of work?

Do we run for the hills, approach gingerly, or simply ignore?

My own response to that question, and the response I fervently hope to persuade you is the only one possible, is best summarized as follows:

It is impossible to overstate just how important - and essential - this release is. And so I would urge you to listen with open ears. And to help you find your way into this repertoire, pray indulge me while I take you on a journey deep into the birth pangs and growing pains of a new type of music that emerged in the opening decades of the 20th century, thanks to Mr. Schoenberg & co.

This set makes the best possible case for diving head first into some of, admittedly, the most challenging music ever written; but it is also some of the most extraordinary music ever written, and definitely some of the most extraordinary sounding music ever written - both qualities amplified by the gorgeous sonics on this Original Source remastering. Yes, a lot of this is “difficult” music, but it rewards the effort, and it remains central to understanding what happened in classical music over a century ago, how everything changed, and why we have the music we have today.

And I’m not just talking about so-called “classical” music here. The “difficulty” of the avant-garde (in all its many hues) that followed in the wake of Schoenberg and his disciples’ “breaking” of classical music (and we must include Stravinsky here too, because he also “broke” classical music, albeit in his own completely different kind of way) - this difficulty is why jazz, rock and popular music in general superseded the classical tradition in popularity for the majority of listeners. It was simply easier to listen to - more ingratiating, more rooted in the familiar diatonic harmonic system which we humans seem to be hardwired to relate and respond to.

But at the same time, there remained something fascinating and alluring about those crazy sounds coming out of the Weberns and the Stockhausens, the Berios and the Ligetis, the Cages and the Pendereckis. Even a committed tonalist like Bernard Herrmann decided a bit of Schoenberg’s 12-tone serialism was just what was needed to convey the madness of Norman Bates in his score for Psycho in 1960 - probably the first time most of the general public was exposed to 12-tone music. (No movie theater revolts ensued - merely abject terror, amplified most effectively by Herrmann’s atonality and tone rows). The more adventurous avatars of pop and jazz were always very aware of what was going on in the corridors and back rooms of progressive Western art music, and sometimes integrated it into their own aesthetic arsenal, with differing degrees of discretion.

"THE EMANCIPATION OF DISSONANCE" - HOW TONALITY ENDED (or What Did Schoenberg Do?)

Arnold Schoenberg in 1927

Arnold Schoenberg in 1927

In order to fully understand what was so groundbreaking about Schoenberg and his followers, it is necessary to understand something of how most Western music, be it classical or not, was structured for many centuries, especially in relation to its tonality and the use of keys, and how that tonality is expressed in “harmony” (the notes placed under a melody to create chords and a sense of where the music is, and where it is heading).

I will try to explain this as simply (and painlessly) as possible!

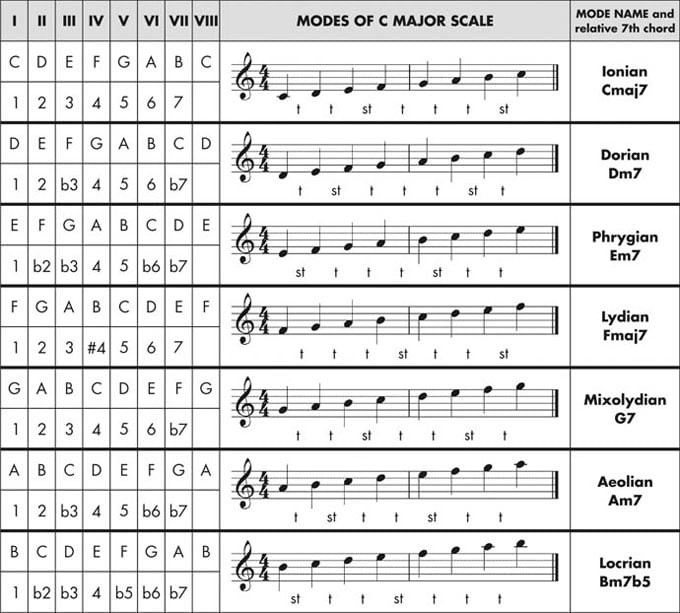

What Schoenberg and his disciples effectively ended - traditional tonality - had driven the development of Western classical music really from the first pieces of music written in two or more parts: music in which “harmony” - that combination of two or more notes vertically, one on top of the other - implied a tonal center, a home key. Earlier monody - music with just one line, like Gregorian chant - did not have that same strong pull towards a “home key” or “tonal center” that can be achieved by combining two or more notes simultaneously. This was because chant was often modal, encompassing a different series of intervals between the notes of the scale from the intervals in the more familiar diatonic scale. (A scale goes from one note - for example a C - to its equivalent either an octave higher or lower). Modal music often sounds key-less, like it could just float endlessly without coming to rest; in fact, it’s just a different sounding, and a differently structured, kind of key and scale to our more familiar diatonic key, built around a diatonic scale.

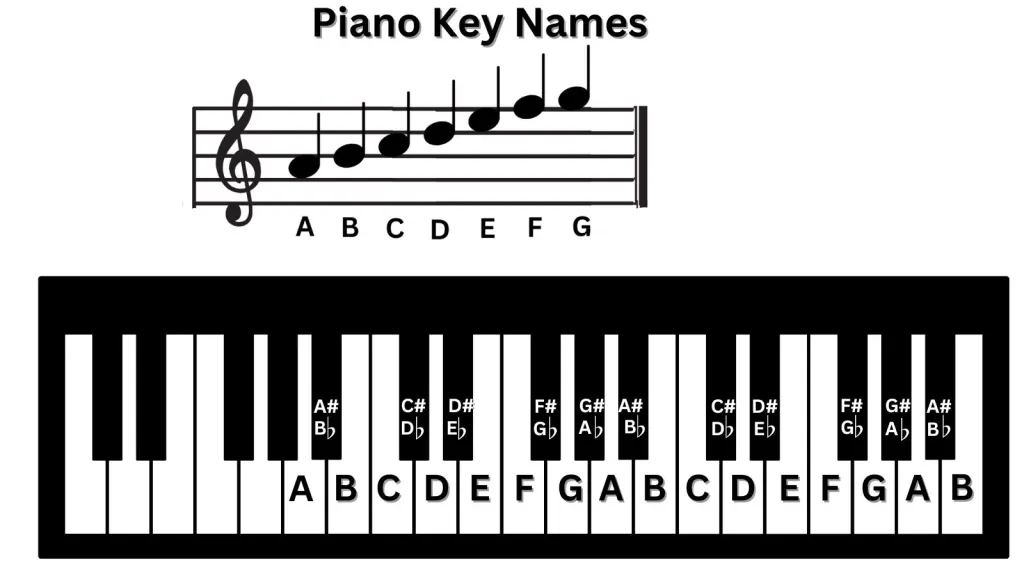

What is a diatonic scale? If you sit at a piano and play a C major scale with one hand (playing all the white notes), the intervals between the notes will vary between being tones (whole steps in American parlance) and semi-tones (half steps). By the time you reach the seventh note of the scale - a B - you will “feel” that the next note has to be a C. By returning to C, you are returning to the “home key”.

Two of the first tunes anyone will learn to play on the piano are “Three Blind Mice” and “Twinkle Twinkle Little Star”. Even if you just play the melody alone to either of these tunes without any other notes, they will both feel like they need to end exactly where they do end - on a C, which is in the home key of C major, the tonal “center” for the music. (if you are playing them in C major). If you substitute a different random note at the end, especially one that doesn’t fit into the regular C major chord (C - E - G - C) that anchors the song, it will sound incomplete and/or wrong. This will earn you a dirty look from your piano teacher, and, in my day as a somewhat recalcitrant pupil, quite possibly a rap on the knuckles from a ruler!

To achieve that sense of inevitable return to the home note, and key - the essence of the diatonic design - a “major” scale is structured as follows:

Tone - Tone - Semitone - (C to D to E to F); Tone - Tone - Tone - Semitone (F to G to A to B to C). (I’m sticking with the English nomenclature because that’s the one I’m familiar with and, naturally, it’s the “correct” one!!!).

The “minor” scale, which sounds “sad” in comparison, is structured differently (again, starting at C in this example - and I’m sticking with the basic minor scale here; there are variations on the minor scale structure which we do not have to go into here):

Tone - Semitone - Tone - (C to D to E flat to F); Tone - Semitone - Tone - Semitone (F to G to A flat to B to C).

This minor scale has been achieved by using what are called “accidentals” - like E flat (aka D sharp) and A flat (aka G sharp) - the black notes on the piano.

If you wanted to play a minor scale on the piano without using any black notes (like the C major scale only plays white notes), you would start on A. “A minor” is known as the relative minor key to C major for that reason; all relative minor keys start a minor third below their relative majors.

When a piece of music is in different keys, ie. G instead of C, or G sharp or B flat instead of C, you start on that different note, but maintain that same sequence of intervals between notes. This will require more “accidentals”.

This is the diatonic system, always pulling the listener towards a home key, which is then further emphasized by putting certain notes and combinations of notes underneath to create chords which, no matter how much they may push the music away from its home key duri ng the course of a piece, will eventually lead you back to the diatonic home key.

“There’s no place like home”.

That sense of tension we hear in most music derives from leaving the home key, and then release and resolution comes from returning to it.

This fundamental notion of building music from a constantly alternating sense of tension and release is what drove the harmonic substance, the tonality, of Western music for hundreds of years. But as composers became more adventurous in their use of chromaticism and deviations from the home key (referred to as “modulation”) - especially during the so-called Romantic era of the 19th century - so too did music develop a more unsettled and unpredictable nature, one more in tune with the more subjective Romantic sensibility.

Before we go any further, I should also mention again those modal scales I referred to earlier. These are based on older forms of music going back to the Middle Ages (with roots in Ancient Greece), and modal scales were more prevalent in, for example, Church music of that period as well as folk music. (The use of modal scales was partly dictated by the less technologically sophisticated nature of early instruments which were restricted in the number of notes they could play in tune, with “accidentals” - the “sharps” and “flats” required to play in keys other than C major - being unavailable or limited). In modal music there isn’t that same “pull” towards a home key - like I said earlier, there is a feeling the music can just continue to “float” without a home key.

But with the ascendancy of more sophisticated forms and instruments emerging during the Renaissance, then the Baroque and Classical eras, the diatonic scale and associated harmony became dominant.

There is something innate, almost an underlying biological imperative, to the diatonic system. It’s about concord (the home key) moving to discord (a “foreign chord” or key) moving back to concord again (the home key). You could even say (and many have) that it is so embedded in the human psyche because it relates to the sexual drive, that sense of building in tension (discord and chromaticism = arousal), moving to a climax that then resolves into post-orgasmic stasis and harmony (the home key). (I discussed this in relationship to Scriabin’s tone-poem, The Poem of Ecstasy; Scriabin was an early experimenter in serial techniques).

No, I am not just being dirty minded - there really is a deep connection between humans’ hardwired biological and sexual drive and the nature of diatonic composition. This sense of building tension through chromaticism and discord, and ending in release and harmony, drives Western music up until the break with atonality that comes about in the early 20th century, and the 12-tone, serial method that Schoenberg develops in its wake. Many have argued that the reason atonality and serialism “don’t work” is because, by suspending that fundamental principal of tension and release, and making the music “all tension”, this kind of music goes against our biological programming, and this is why it appeals more to our heads than our hearts.

In fact, it is that very sexual dimension of diatonic tonality which Richard Wagner exploited so brilliantly in his opera Tristan und Isolde (1859) and by doing so initiated the inevitable march towards the suspension of that same diatonic tonality some fifty years later.

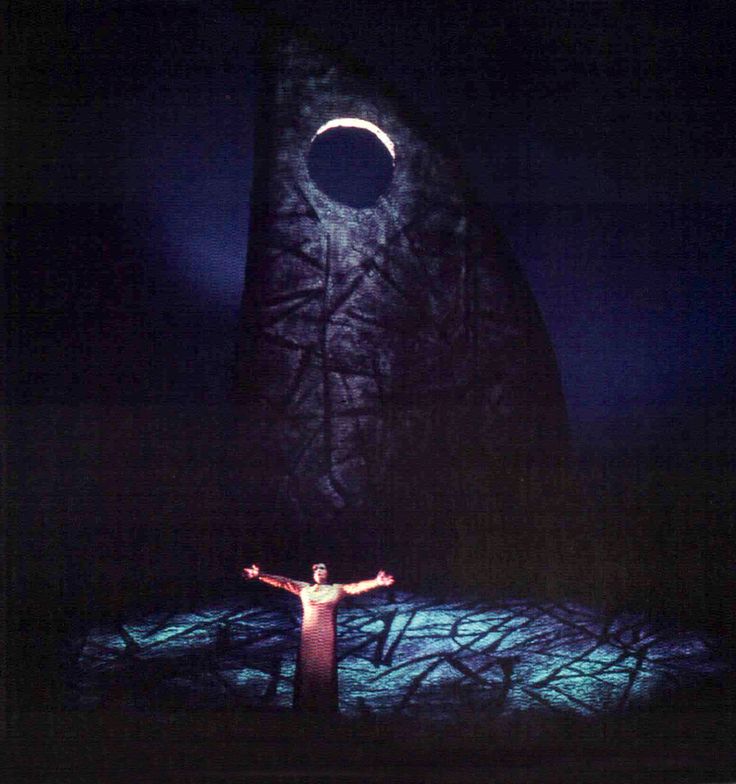

Karajan's 1972 production of Tristan und Isolde, with set design by Günther Schneider-Siemssen

Karajan's 1972 production of Tristan und Isolde, with set design by Günther Schneider-Siemssen

Tristan und Isolde is the four-hour tale of a passionate love affair that is only finally consummated in death - literally - as Isolde expires upon the body of her dead lover. Musically, it is a four-hour tease, a tonal coitus suspensus et interruptus. The so-called “Tristan chord” which opens the Prelude, and which recurs throughout the work, is a yearning musical phrase and chord whose underlying progression never finds the home key - until the very end of the opera when Isolde dies. Whenever you think that chord, that phrase, that music is going to resolve, it goes somewhere else. It has a constantly roving musical eye…

The resolution does not arrive until Isolde sings her final Liebestod (“Love in Death”) over her beloved Tristan’s dead body, and as she expires the music finally, after four hours, resolves into its home key: it has its orgasm and release - just as Isolde finally does onstage.

Isolde's Liebestod in Wieland Wagner's 1962 Bayreuth production. Wieland Wagner's post-War productions broke new ground in opera and theater production through their use of abstract sets, moody lighting, and new approaches to stagecraft

Isolde's Liebestod in Wieland Wagner's 1962 Bayreuth production. Wieland Wagner's post-War productions broke new ground in opera and theater production through their use of abstract sets, moody lighting, and new approaches to stagecraft

In the famous Act 2 Love Duet, when it seems like the lovers are going to finally consummate their passion, they are rudely interrupted, as is the music’s seemingly inevitable progress towards a harmonic resolution. It is a true musical coitus interruptus reflecting the one onstage: as the home key is sideswiped by an imposter chord announcing the arrival of Isolde’s jilted betrothed, who happens to be the King. (After that things don't go too well for our lovebirds).

The manner in which Wagner masterfully controlled his harmonic design, using intricate chromaticism and associated chordal ambiguity to effectively “suspend” traditional tonal progression, hit the musical world like a sledgehammer. Traditional tonality was now up for grabs. Composers as diverse as Bruckner, Richard Strauss, Mahler, Liszt (who had led the way towards the dissolution of tonality hand in hand with Wagner) began to push the boundaries, with their music becoming ever more harmonically remote and un-centered. Debussy, once a fervid Wagner acolyte, found a different way to upend conventional tonality by embracing modal harmony. His ground-breaking work, Prélude à L’après-midi d’un Faune (Prelude to the Afternoon of a Faun), which premiered in 1894, is considered a marker for the beginning of modernism because of his embrace of modal harmony, new procedures and form.

(And for the jazz aficionados amongst you, that same adoption of modal harmony is what made Miles Davis’s album Kind of Blue a marker for a new age of jazz composition and improvisation, echoing what had happened in classical music some fifty years earlier).

Schoenberg in 1903

Schoenberg in 1903

So this is where Arnold Schoenberg found himself at the outset of his career in turn-of-the-century Vienna, working in the very long shadow of Wagner’s innovations. Largely self-taught, an autodidact in the best sense of the word, Schoenberg did most of his more formal study under the watchful eye of Alexander von Zemlinsky (a seriously underrated composer whose works I urge you all to explore).

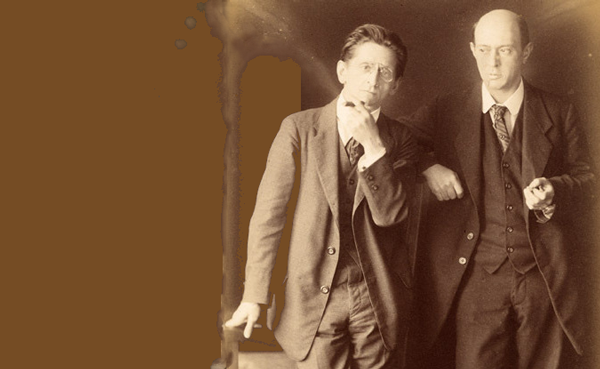

Alexander Zemlinsky and Schoenberg in Prague, 1917

Alexander Zemlinsky and Schoenberg in Prague, 1917

Along the way Schoenberg fell in love with, and married, Zemlinsky’s sister Mathilde, providing the inspiration for Verklärte Nacht (Transfigured Night), which is suffused throughout with an aura of romantic euphoria (caught thrillingly in Karajan's definitive recording of the orchestral version).

Mathilde and Arnold Schoenberg

Mathilde and Arnold Schoenberg

Schoenberg’s early works, like Verklärte Nacht, Pelleas und Melisande, the First String Quartet and the massive choral work Gurrelieder are fully cast in the post-Wagnerian, late-Romantic mold of intense chromaticism and harmonic ambiguity. But even by those standards, these early works of Schoenberg are dense and hard to wrap one’s ears around (with the exception of Verklärte Nacht). It’s almost as if there is just too much music going on; or, to quote Emperor Joseph II’s critique of Mozart in Amadeus: “There are simply too many notes…!”

Where to next? Well, the thinking went, if you have this much chromaticism and harmonic ambiguity going on, isn’t the next logical step to just say that all harmony is created equal, and ignore the pull towards a home key? Would there really be that much difference between tonality where you never go to the home key, and atonality where you simply say there is no home key?

This is essentially what atonality is - a suspension of tonality. Schoenberg dived in head first with the Second String Quartet (1908), in particular the last couple of movements which add a vocal soloist. What is refreshing about this work in comparison to the First String Quartet is the distillation of means. Gone is the almost indigestible chromatic gloop (even though it’s lovely gloop), and in its place is something more streamlined and concentrated. There is a sense of the composer harnessing his resources, and the end result is more direct and bracing.

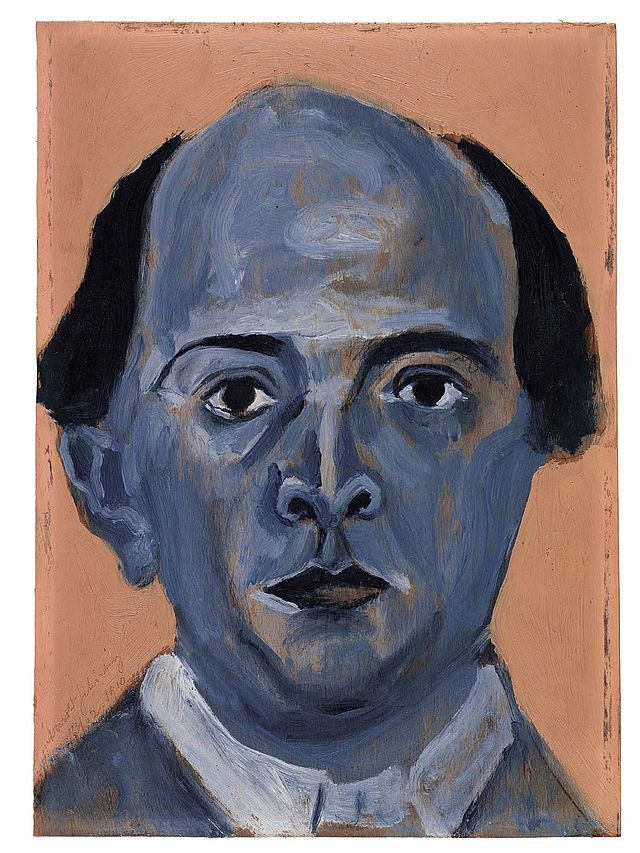

Schoenberg also became an accomplished painter. This is a self-portrait from 1910, shortly after he had fully adopted atonality

Schoenberg also became an accomplished painter. This is a self-portrait from 1910, shortly after he had fully adopted atonality

In a letter to Ferrucio Busoni in 1909, when he was in the thick of his move into atonality, Schoenberg wrote:

I strive for complete liberation from all forms… Away with harmony as cement or bricks of a building. Harmony is expression and nothing else… My music must be brief. Concise! In two notes: not built, but “expressed”!!

I think this is the key to unlocking Schoenberg’s music across the span of his creative life. The density of his early “romantic” works, still written in tonality, but thick with almost impenetrable chromaticism that can obliterate melody and an easy through-line, becomes easier to grasp if you think in terms of it being “expression and nothing else”. Likewise this opens a door into his more ostensibly “difficult” works from his atonal and serial periods: listen to the music in the moment, open yourself to the “expression” rather than listening for the through line. The “expression” - which in Schoenberg’s case is always intense - will carry you along.

Later in life, talking about the embrace of atonality, he declared himself “intoxicated by the enthusiasm of having freed music from the shackles of tonality”. This feeling led him to seek “further liberty of expression.” ["Schoenberg - Why He Matters" Harvey Sachs, page 64].

It was Schoenberg’s pupil Alban Berg who must vociferously pursued this notion of "further liberty of expression", writing music that, while adopting atonality and serialism, also connected the most with audiences via its overt emotionalism. In this regard it was, in many ways, more backward looking than that of his teacher, and of his fellow student, Anton Webern, who was moving ever more relentlessly towards complete distillation and compression of expression. Berg's full embrace of that most overtly dramatic and emotional of musical forms - opera - seemed to underline his old-fashioned streak. For many, it is Berg’s music which remains the most viscerally appealing, and relatable, of the Second Viennese School triumvirate.

Alban Berg with his teacher in 1914

Alban Berg with his teacher in 1914

Going back to Schoenberg. Even as he thoroughly explored atonality, he felt the pull towards creating order out of chaos, because indeed there remained a chaotic element to atonality, something that maybe needed controlling for the sake of everyone’s sanity. It was, after all, defined by its rejection of a system - and how far can that take you?

So, Schoenberg argued, in this new world order I am creating, let us build upon this notion that every note in the scale has equal weight and significance. With no tonal system pulling us towards a home key, then it makes total sense to say that every note, every chord has equal weight. A complete musical egalitarianism. The new order will come from how we choose to order these “tones”, these “twelve tones” that make up the octave scale. A work’s “theme” or “melody” will now be those twelve notes, stated in either a monodic or chordal form, or both, and then those notes, this so-called “tone row”, will be subjected to mathematical and other manipulations along various carefully laid out formal procedures (inversion, retrograde, retrograde-inversion etc.). Thus a new language of musical melody and harmony will proceed.

Of course I am simplifying enormously, but that is the gist of what became the 12-tone method (also known as serialism, or dodecaphony).

In 1921, on a summer’s evening walk with his pupil Josef Rutfer, Schoenberg announced his breakthrough:

“Today I succeeded in something by which I have assured the dominance of German music for the next century.”

Schoenberg self-portrait from 1925

Schoenberg self-portrait from 1925

Interestingly, Schoenberg himself resisted the “labelling” of his new method.

He opposed analyses of twelve-tone “rows” because, he said, “this leads only to what I have always fought against: the realization of how it was done, while I always aimed for the recognition of what it is!” In other words, people should listen to music for its intrinsic expressive value without having to think about how it was put together.” ["Schoenberg: Why He Matters" by Harvey Sachs, page. 130]

In other words, we are back to what Schoenberg was saying about his music in that letter to Busoni that I quoted earlier in this article:

“I strive for complete liberation from all forms… My music must be brief. Concise! In two notes: not built, but “expressed”!!”

In the process of venturing beyond the traditional demands of diatonic harmony, Schoenberg believed he had achieved what he would later call the "emancipation of dissonance". He had obliterated the traditional hierarchies of consonance and dissonance. All notes and chords were equal now, perceived as the same.

Or were they? Was it really that easy to just re-program the way we reacted on a fundamental biological level to the different properties of consonance and dissonance?

What happened over the next century of music, culminating in the return to diatonic principles, would seem to suggest that the emancipation Schoenberg most devoutly wished for, and felt had been achieved, was illusory.

The 12-tone method was the form and manner in which Schoenberg predominantly composed for the rest of his life (with the occasional detour back to tonality, for example in his Second Chamber Symphony of 1939, but begun in 1909).

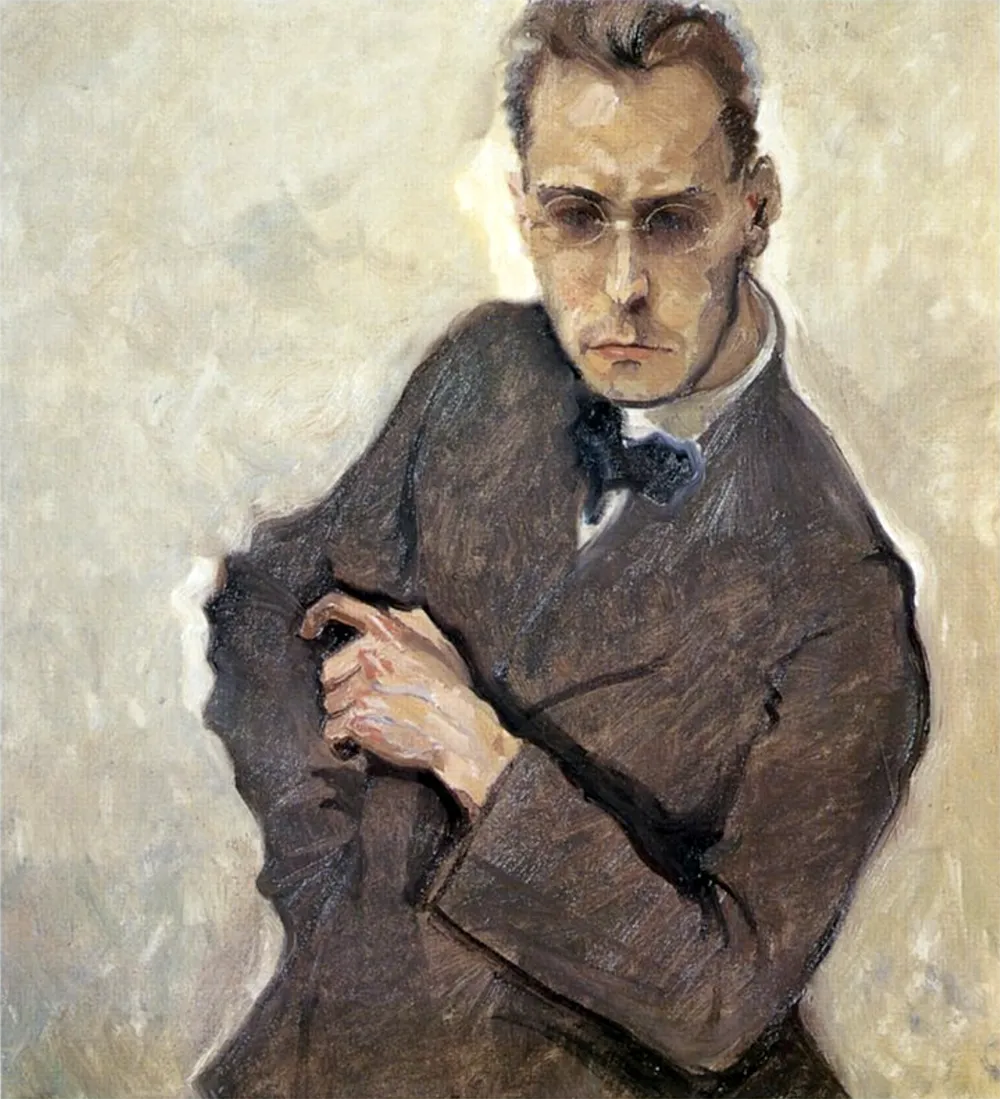

Anton Webern - Portrait by Max Oppenheimer in 1908

Anton Webern - Portrait by Max Oppenheimer in 1908

His pupil Anton Webern took Schoenberg's atonality and serialism to an even more extreme level of distilled and purified procedure, with short works comprising movements that often lasted only one or two minutes. That’s all the time he needed to make his point. That distillation, that “paring-down”, results in music that can feel like an atomic reaction being freeze-framed at different stages of its expansion. Finally, in the fourth Langsam - Funeral March movement of the Six Pieces for Orchestra Op. 6 of 1910 (included on the Webern disc in this set), the chain reaction finally goes completely nuclear, consuming the world with its intensely felt sense of loss.

Schoenberg with pianist Leopold Godowsky (l.) and Albert Einstein (c.) at Carnegie Hall in 1934

Schoenberg with pianist Leopold Godowsky (l.) and Albert Einstein (c.) at Carnegie Hall in 1934

Schoenberg himself insisted that the direction in which he took music was a natural evolution, not a revolution - an extension of the musical procedures that had gone before. (Others, hearing the audible results, disagreed). In a 1949 lecture he titled “My Evolution”, given at UCLA’s Royce Hall, Schoenberg looked back on what he had done:

“In fact, I myself and my pupils Anton von Webern and Alban Berg… believed that now music could renounce motivic features and remain coherent and comprehensible nevertheless… New characters had emerged, new moods and more rapid changes of expression had been created, and new types of beginning, continuing, contrasting, repeating, and ending had come into use. Forty years have since proved that the psychological basis of all changes was correct. Music without a constant reference to a tonic was comprehensible, could produce characters and moods, could provoke emotions, and was not devoid of gaiety and humor.”

Humor of a particularly dour Teutonic bent, I would say… (Humor, certainly of a Mozartian hue, is not a quality one associates with the music of the Second Viennese School).

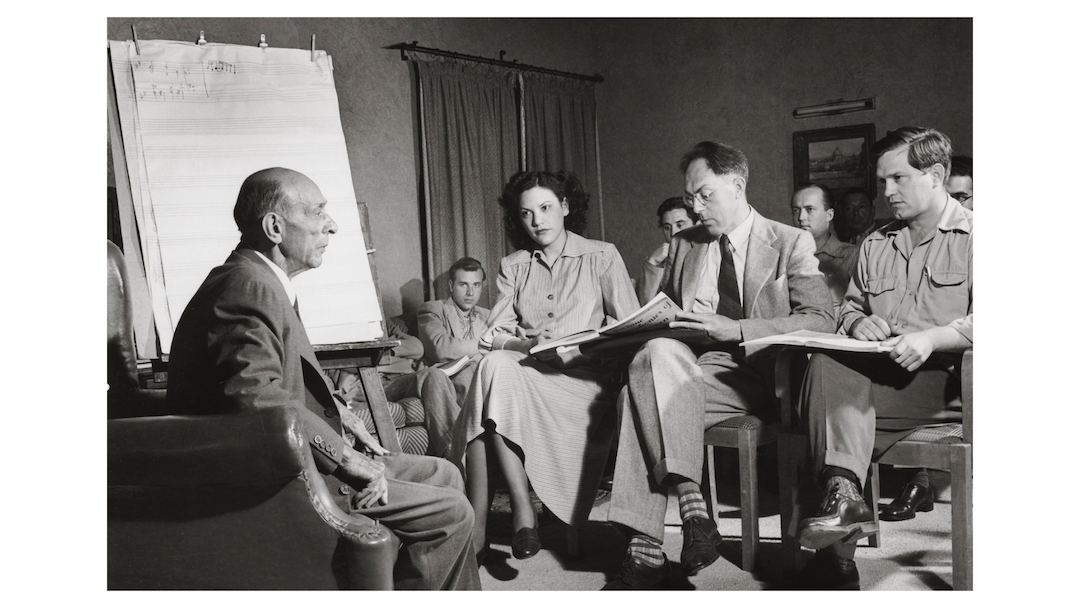

Schoenberg teaching in Los Angeles in 1948. He was considered an inspiring, thoughtful teacher by his pupils, and it was one of the most far-reaching aspects of his legacy

Schoenberg teaching in Los Angeles in 1948. He was considered an inspiring, thoughtful teacher by his pupils, and it was one of the most far-reaching aspects of his legacy

The 12-tone, serial method was widely adopted by the next generation of composers who were considered in the vanguard, the avant-garde, of new musical thought - composers like Pierre Boulez, Luigi Nono, Milton Babbitt and Karlheinz Stockhausen. Subsequent, more extreme forms of serialism mathematicized every aspect of music, including rhythm, dynamics, even pitch. Composers who retreated from this method into neoclassicism (like Paul Hindemith, even Stravinsky who had pioneered the neoclassical style), or ignored it altogether (like Shostakovich and Benjamin Britten) were considered irrelevant reactionaries, doomed to be the last practitioners of a dying art. Until, of course, they weren’t. Their traditional tonal music survives and thrives while thousands of serial and atonal compositions sit unplayed in the back of dusty cupboards.

The tables were definitively turned in the last decades of the 20th century, when a return to tonality via the minimalist composers Terry Riley, Steve Reich and Philip Glass stamped an expiration date on serialism. (Riley’s groundbreaking composition In C made no bones about re-establishing the primacy of tonality via the primal C chord which is repeated for as long as it takes, sometimes hours as in one daylong performance a friend of mine took part in at UCLA's Hammer Museum). On the way there, even another revolutionary, Stravinsky - who had done his own upending of the Western classical tradition through works like The Rite of Spring (1912) and its detonation of his own version of rhythmic and tonal subversion - turned to serialism as a viable compositional method. Ironically, his serial compositions are amongst his least known, performed or even liked, even though he clearly felt this was his way forward later in his composing life.

I myself have always found this period of music fascinating, yet I have also struggled (and continue to struggle) with many of these works throughout my time of listening to them. I am still learning - and still being rewarded (but also sometimes frustrated) by my efforts.

For anyone wanting to engage and grapple with this extraordinary one-of-a-kind music, this Karajan box is more than just the ideal starting point. It proselytizes more effectively than most, if not all, rivals, for not just accepting, but loving, this music.

On record, it is Ground Zero for the nuclear firestorm that is the Second Viennese School.

In Part 2, I survey the history of recordings of the Second Viennese School released prior to Karajan’s set (and of music by the composers who followed in Schoenberg’s wake). I examine why this DG set was such a significant release - which also turned into a surprise sales juggernaut, to everyone’s surprise.

In Part 3, I talk about Karajan’s history with the Second Viennese School, and his distinctive and fastidious approach to preparing and recording these works. That is followed by a detailed examination and review of each record in the set, plus some suggestions for further listening and reading.

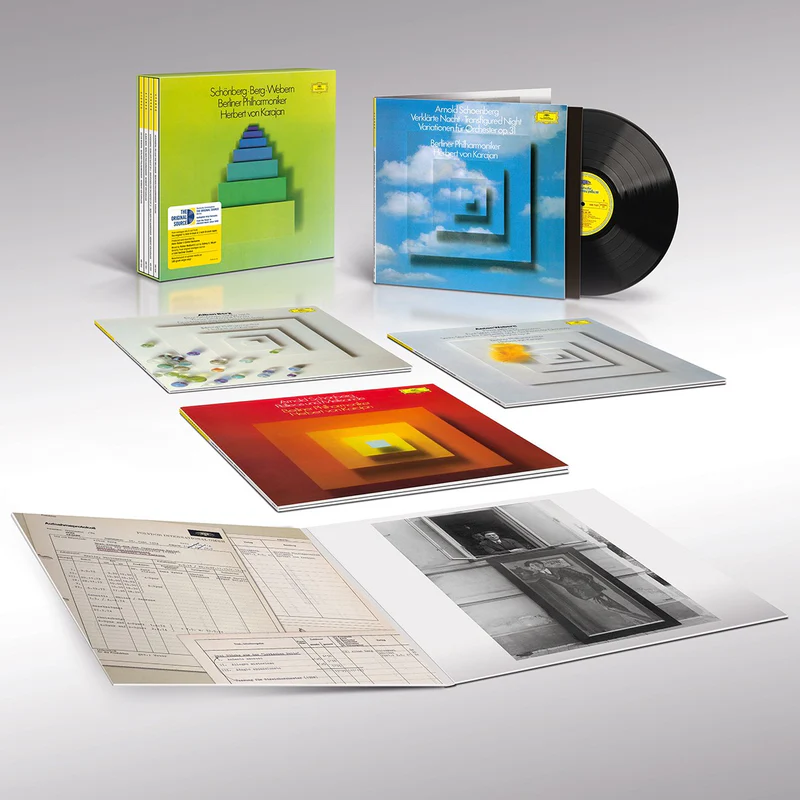

Available at Acousticsounds.com

.png)