Over the Rainbow - New Light Shed on Neil Ardley’s Masterpiece

A Seminal Moment in British Jazz/Rock Fusion from the 70s Gets the Definitive Vinyl Outing

(Photo courtesy of Neil Ardley Estate)

(Photo courtesy of Neil Ardley Estate)

There are moments in your life when you first come into contact with a particular piece of art - be it music, theatre, a film, a painting, whatever - and it makes such an impression that the moment remains with you as a living memory, existing in an eternal present.

This record is like that for me. It has lived with me, and taken a polar position in my internal musical jukebox as vividly, as prominently, as resonantly, as the day I first heard it nearly 50 years ago.

So be prepared - I’ve got a lot to say about this record.

But it’s worth saying, and it’s worth you taking the time to read what I’ve got to say, because this is special, unique music: fresh, groundbreaking, intoxicating, surprising - and really fun to listen to.

Over.

And over again.

Trust me. I’ve listened to this record a lot!

And now, thanks to this exquisite release, the epitome of an audiophile vinyl reissue done right, I am listening to it again as if for the proverbial first time.

And I’m having an absolute blast.

Today, there are many ways in which a 16-year old discovers new music, mostly rather prosaic ways, often via those Orwellian algorithms, but back when I discovered this record the process had an altogether more romantic aspect.

You see, I was on a date. A date with my radio.

I know that sounds a little freaky (!) - it really isn’t… And before you howl “Nerd!” and mock, let me explain that growing up in England when I did, radio was very much a part of the fabric of daily life. For many it still is. It wasn’t the kind of radio you get here in the States, although we had that too with DJs on BBC Radio 1 and 2, then commercial Capital Radio, let alone the pirate radio channels broadcasting from offshore waters. On Radio 3 (the classical channel), Radio 4 (essentially talk) and the BBC World Service there were specific programs throughout the day of which many were appointment listening for the nation. Programs like the long-running soap, The Archers, The World at One, comedy shows and radio plays, Question Time, Record Review, The Week’s Composer, and, in the summer, the Proms, and so on. We made appointments to listen to certain programs. Sometimes we even recorded them on cassette - I’ve still got a bunch of those. including the first broadcast of The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy (its first incarnation was as a weekly radio show in 1978).

Back in 1976, one program that had just flown onto my radar was Radio 3’s Sounds Interesting, hosted by Derek Jewell. Jewell was one of the foremost writers on music of his day, the music critic for The Sunday Times covering jazz, rock and other non-classical music, and on Saturday afternoons he hosted a weekly show that featured what he thought currently “sounds interesting”, and sometimes live performances. By 1976 this had become a really important venue for breaking new, adventurous music - or offering a more serious perspective on mainstream rock. (A year later I discovered Jethro Tull via Jewell’s brilliant breakdown of their then new album, Songs from the Wood).

My background had mainly been in classical - playing and singing since I was 7 - but in recent years I had started to seriously explore jazz and rock, mainly through records. So there I was, tuning in one Saturday afternoon when I was 16, and Jewell - a critic who communicated his enthusiasms with scholarly but digestible erudition and insight, but also with enthusiasm and verve - was raving about this new record called Kaleidoscope of Rainbows. What really caught my attention was the fact that Jewell talked about how he felt this music broke new ground in terms of marrying the improvisational elements of jazz with the more formal, composed nature of classical music over a longer time frame than had hitherto been accomplished. Achieving this synthesis had long been a goal of countless classical and jazz musicians and composers, but it had proved elusive.

Until this record.

The essence of what Jewell had to say about this music on the radio is conveyed in the liner notes he contributed for the original album, and reproduced here on this reissue. Here are some salient extracts:

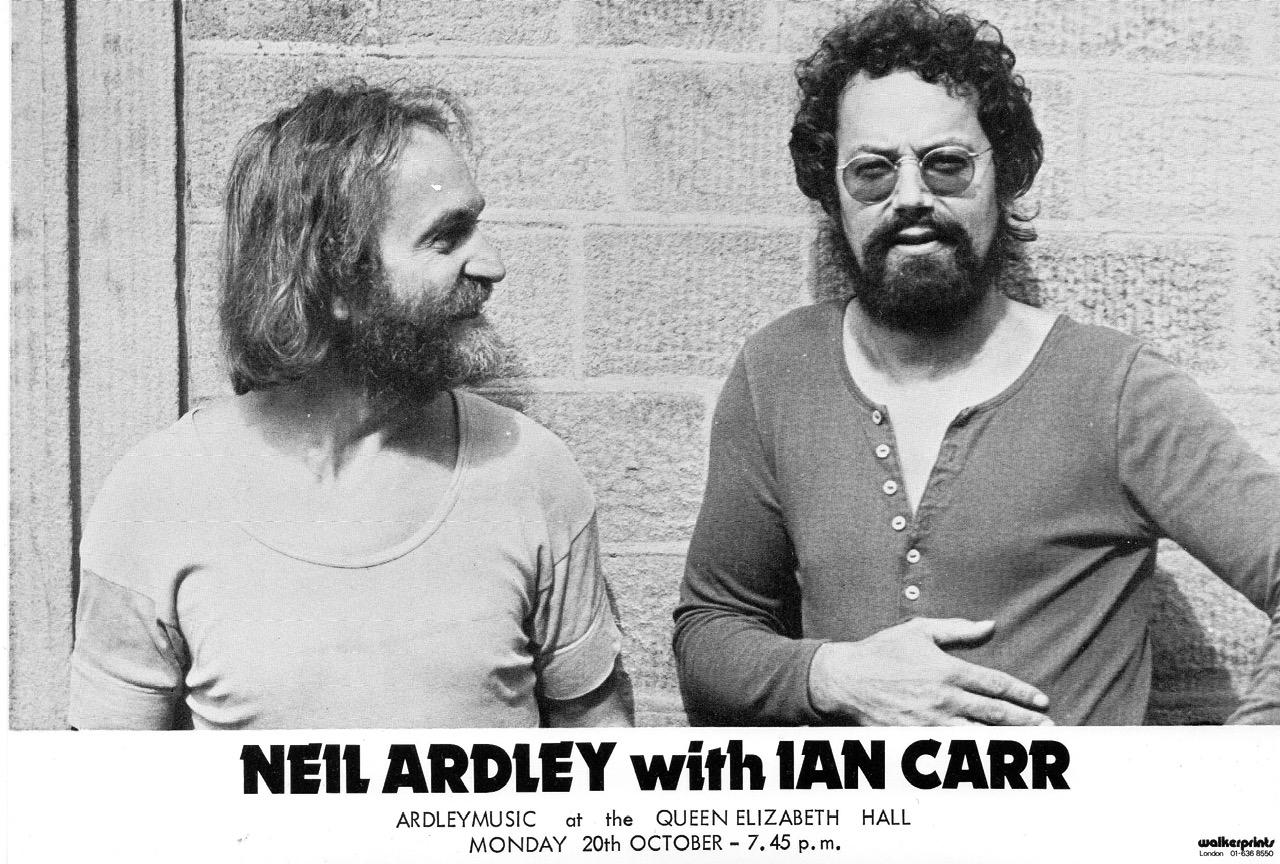

I don’t believe I’ve ever had an evening in a concert hall more surprising, more enjoyable, more totally satisfying than that of October 20th, 1975. That was the day when Neil Ardley premiered his expanded version of “Kaleidoscope of Rainbows”… re-worked and lengthened for concert presentation by a dozen strong group of musicians.

That weekend, my pleasure (I hope) came through in “The Sunday Times”. “A triumph… important for the cause of modern music of quality in Britain… inspired… Ardley is in the line of Ellington and Gil Evans in his audacious imagination.”

… from my viewpoint this is music which in its effect upon the listener throws away texts. It’s barrier-breaking, life-enhancing music, and that’s its importance.

Whether composed or improvised. the sounds often have the bite of good jazz and rock. There’s an illusion of spontaneity about the music, yet beneath the surface there is sound and muscular structure. Themes are stated (Neil Ardley writes good melodies) and cunningly developed, with the undertow of repeated bass patterns always holding the music together however wildly the sounds swirl above them.

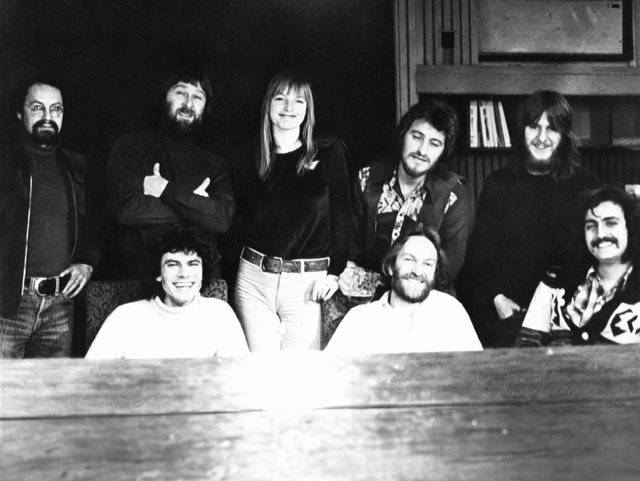

Slow and steady some of the music is; cheerful and witty parts are in there too. In effect it’s a tour through the whole modern landscape - with rock, jazz, Latin-American and symphony flowing together - played by musicians who are plainly at ease in this mixed environment and understanding each other. And this mixing of stylistic influences is exactly what today’s music is about, of course - a fact underlined on this album by the presence in the band of men like Tony Coe, who’s played with Count Basie, as well as Matrix, the avant garde ensemble; Paul Buckmaster, arranger for Elton John and co-writer with Miles Davis, on ‘cello; and Ian Carr, leader of the highly respected Nucleus, which forms the core of the band.

Another distinctive presence in the band is the great Barbara Thompson on alto and soprano sax, plus flute, whose solo in Rainbow Four is one of the highlights of the album.

(back row, from l. to r.) Ian Carr (trumpet, flugelhorn); Colin Richardson (New Jazz Orchestra Manager); Barbara Thompson (alto, soprano sax, flute); Roger Sutton (bass guitar, electric bass); Martin Levan (engineer). (front row, from l. to r.) Paul Buckmaster ('cello, Producer); Neil Ardley (synthesizer, Director); Chris Tsangarides. (Used with permission of Neil Ardley Estate)

(back row, from l. to r.) Ian Carr (trumpet, flugelhorn); Colin Richardson (New Jazz Orchestra Manager); Barbara Thompson (alto, soprano sax, flute); Roger Sutton (bass guitar, electric bass); Martin Levan (engineer). (front row, from l. to r.) Paul Buckmaster ('cello, Producer); Neil Ardley (synthesizer, Director); Chris Tsangarides. (Used with permission of Neil Ardley Estate)

Anyone familiar with Ardley’s next album, Harmony of the Spheres, which I reviewed here in March, will have some idea of what to expect on this record. I will say that in general this is a jazzier album, whereas HOS leaned a bit more towards prog rock elements, giving a more featured role to synthesizers. (Synths are an important element of Kaleidoscope too, lending a distinctive timbre to the proceedings that is in no way dated).

In fact one of the things you will come away with from listening to this record is just how modern and un-dated the music sounds, how alive and in the moment it is (partly a product of being recorded largely “live” in the studio, with minimal overdubbing).

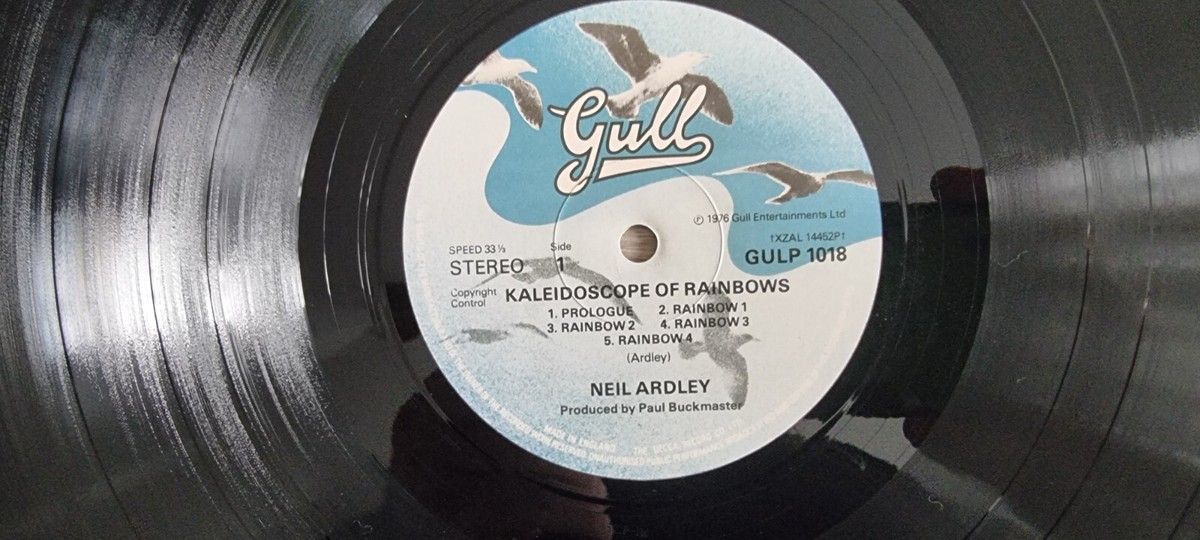

Let’s take a moment here to quickly mention the sound. This was always a phenomenal sounding record, released on Gull Records, founded in 1974.

In the extensive and detailed essay contained within the luxurious booklet that comes with this reissue, you can read in detail about how this was achieved. Suffice it to say that engineer Martin Levan - here at the beginning of his career, but soon to become a legend in the business - collaborating with Paul Buckmaster inside the equally legendary Morgan Studios, created an aural palette into which the listener sinks, from which every detail emerges effortlessly, but which also conveys the sense of both a true orchestra of musicians, but who also respond and play off each other like a long-time band. Those of you who also know Andrew Llyod-Webber’s Variations from 1978 (and have read my article about it on this site) will recognize a similar vibe to that record - which was also engineered by Martin Levan at Morgan Studios, and also featured contributions from Barbara Thompson.

So who was Neil Ardley, and how did he achieve this brilliant synthesis of disparate musical elements?

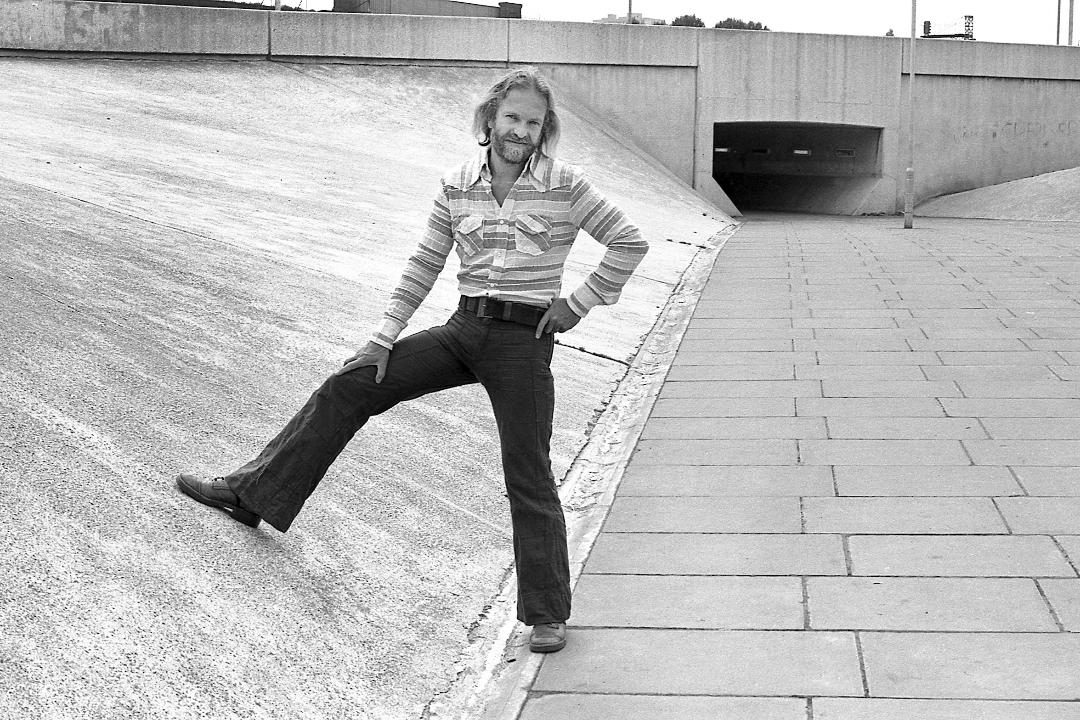

Neil Ardley (photo by Martyn Goddard)

Neil Ardley (photo by Martyn Goddard)

To kids and science geeks in the 70s and 80s Ardley would have been known as the author of books introducing them to all manner of science topics, like Experiments with Heat, Life in the Open Sea, Wonders of the World, Exploring Magnetism, and a whole series of books under the theme of The World of Tomorrow. He had learned his editorial craft as a member of the team putting together the World Book Encyclopedia. His interest in space and the universe showed itself early, and would directly influence his music in Harmony of the Spheres. Key books which remain in print in updated editions are The Way Things Work and 101 Great Science Experiments. He channeled his passion for music through books like Sound and Music and A Young Person’s Guide to Music.

His writing was what put food on the table, but music was his true love, and, although largely self-taught as a pianist and sax player, he quickly entered the UK jazz scene after university via the John Williams Big Band (a different ‘John Williams’ from the one you're thinking of). Here he also started composing and arranging, skills he further developed when he became Director of the New Jazz Orchestra in 1964. This is where he met many of the players and future collaborators on his own future albums, musicians like Ian Carr, Barbara Thompson, Jon Hiseman, Dave Gelly, Michael Gibbs, Don Rendel and Trevor Tomkins.

In his Guardian remembrance of Neil, musical collaborator John L. Waters wrote:

I first met Neil in 1971, when he taught me at the Barry Summer School, where I was struck by his enthusiasm and depth of knowledge. I subsequently studied composition with him and our paths crossed many times after then. He borrowed musicians from my band - having asked politely whether I would mind - and I introduced him to early music computers such as the Roland MC8, which he quickly learned to program. In the late 1980s, together with Ian Carr and multi-instrumentalist Warren Greveson, we formed Zyklus, an "electronic jazz orchestra", for occasional gigs…

Neil's best work synthesizes the rigours of composition with the spontaneity of improvisation, and features finely nuanced part-writing for woodwinds and strings. He had an idiosyncratic ear for orchestral colour, a classical composer's ability to create long, through-composed pieces from a handful of motifs and a jazz bandleader's ability to write for specific personalities. Yet his compositional voice was clearly English, almost pastoral, with a breezy confidence that mirrored the rising status of European jazz.

Kaleidoscope of Rainbows represented the summation of Ardley’s aspirations towards creating a new kind of music that did indeed fuse together classical, jazz and rock elements. It was the third part of a trilogy of albums, proceeded by Greek Variations and A Symphony of Amarinths.

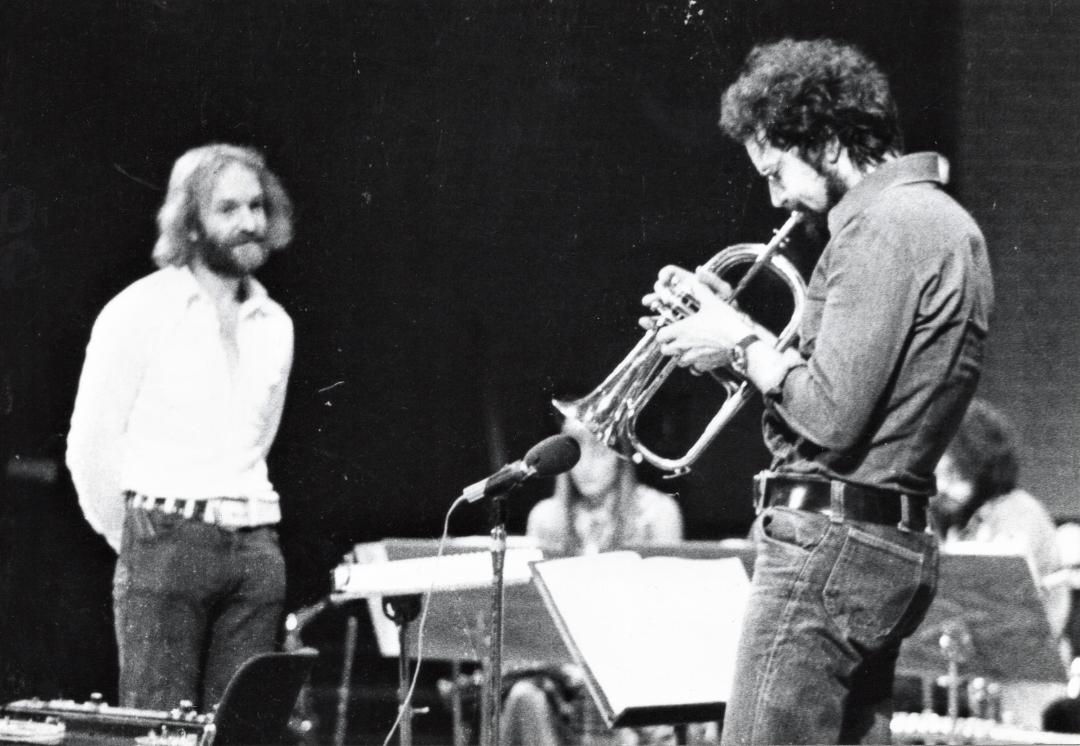

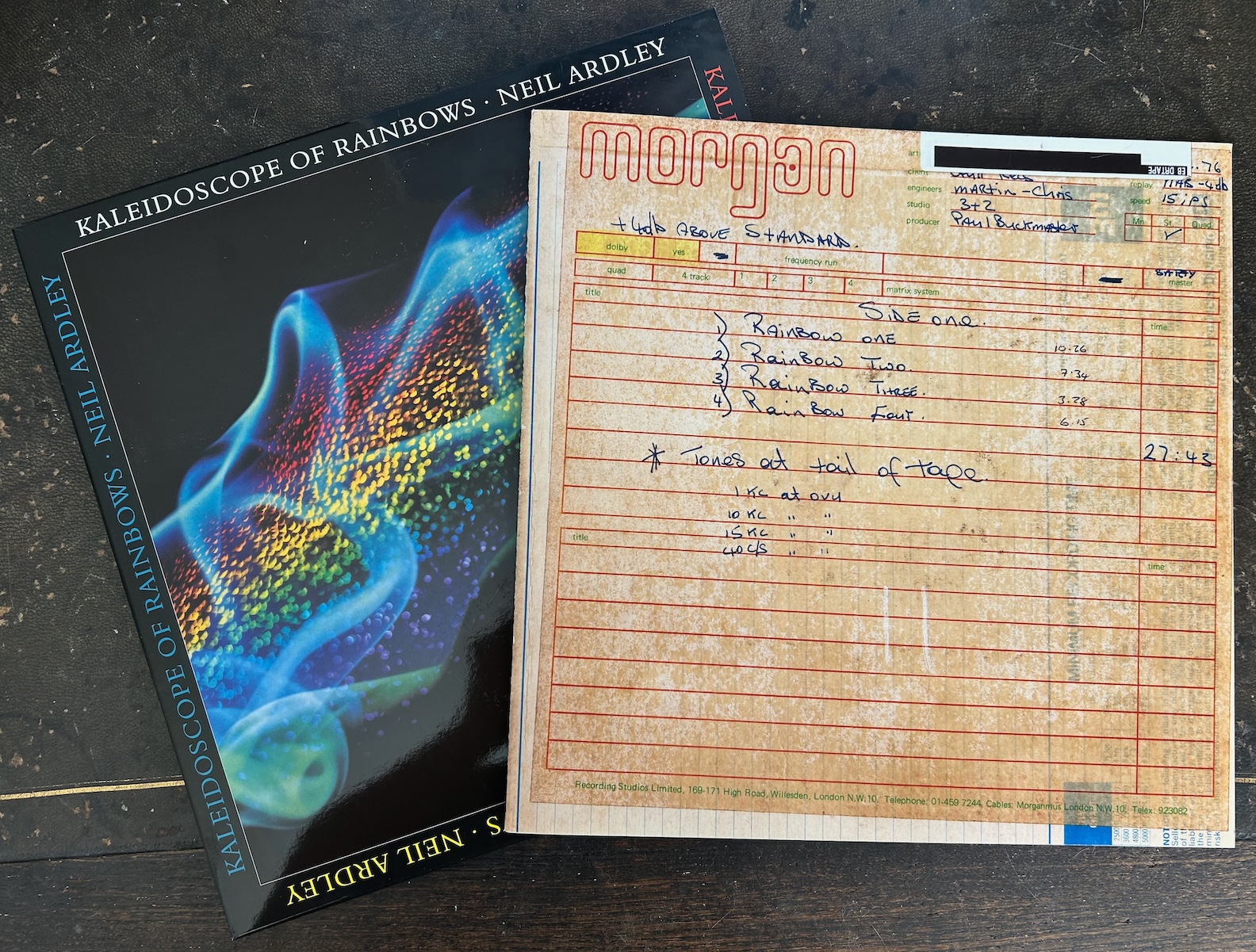

The full background and history of the album is covered in great detail in the superb essay by Mike Flynn, Editor of Jazzwise Magazine, that is the backbone of the lavish booklet included in this reissue, peppered with wonderful session photos, photos of the score and the obligatory shots of master tape boxes. Shout out to the beautiful design work of Tim Rogers.

A sample of the beautiful design work by Tim Rogers for the Analogue October reissue of Kaleidoscope of Rainbows

A sample of the beautiful design work by Tim Rogers for the Analogue October reissue of Kaleidoscope of Rainbows

Rather than paraphrase all this fascinating material, let me focus in on a few key elements of the story that Flynn tells.

Ardley found inspiration for KOR in the music of Bali. He was not the first to be drawn to the exotic timbres and unusual, non-Western harmonic design of the gamelan orchestras of that island nation. Ravel and Debussy had discovered the instrument and its music at the 1889 Paris Exposition, and its influence immediately became apparent in their works. Benjamin Britten, already familiar to a degree with Balinese music from composer Colin McPhee (who had lived in Bali throughout the 1930s), had studied the music in greater detail while holidaying in Bali in 1956, integrating the Balinese scale and sonorities into his music for the ballet The Prince of the Pagodas (1957).

Benjamin Britten (l.) and Peter Pears in Bali in 1956

Benjamin Britten (l.) and Peter Pears in Bali in 1956

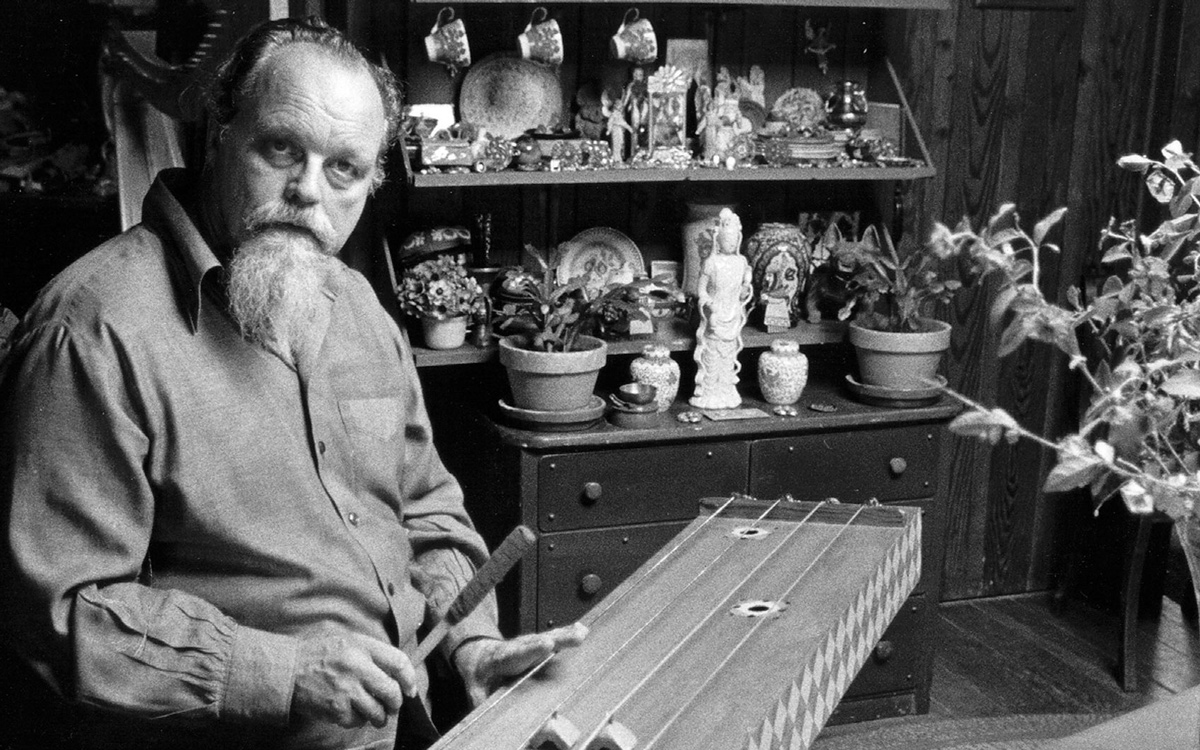

Another composer who was heavily influenced during this time was the American Lou Harrison.

Ardley:

The trigger for “Kaleidoscope of Rainbows” was Denis Preston who produced “A Symphony of Amaranths”. After we’d recorded it he gave me an LP saying, ‘I think you might like this.’ It was a collection of Balinese music, and I thought it was wonderful. But at first I couldn’t figure out how it fitted together, musically speaking. So I went along to Westminster Music Library and got out several books on the music of Bali, until I’d figured out the five note Balinese scales, and then I took it from there…

Gamelan Orchestra (from the Colin McPhee archive at UCLA)

Gamelan Orchestra (from the Colin McPhee archive at UCLA)

Flynn:

The album’s seven movements, or ‘Rainbows’, plus an additional prologue, are all based on a five-note scale - of noted D, E, G sharp, A and C sharp - and Neil saw the possibilities of expanding these five notes into a suite of contrasting movements. [Ardley:] “I was enchanted by the sound of the music, particularly its tonality, and raced to the music library to find out how the people of Bali put their music together.” In fact the limitations of this five-note scale chimed with Neil’s compositional style: “This excited me as my two previous works had both been based on note sequences. ‘Greek Variations’ on a short Greek folk tune, and ‘A Symphony of Amaranths’ on the notes DE and GE - for my jazz mentors, Duke Ellington and Gil Evans.”

Two things contributed to KOR achieving a level of sophistication and fully-realized intent and accomplishment that eclipse its predecessors.

One was the fact that the work itself would be worked on extensively over a period of three years in live shows, with a group of musicians Ardley had worked with beforehand. Earlier performances resulted in Ardley moving away from a more traditional brass-heavy jazz band sonority towards something more eclectic and modern.

Ardley:

I thought well, I am going to go to Ian Carr, who… had a very fine band called Nucleus, which is a jazz-rock band. And he would perform with Nucleus and I could have that as an orchestra, and on top of that I added Dave McRae on electric piano and synthesizer; still four woodwinds, because I’m intrigued with woodwind colour - flutes, bass clarinet, soprano saxophones; then Paul Buckmaster on electric ‘cello, grooving away with the piano, pressing the wah pedal. Marvelous isn’t it? [To hear just how marvelous, check out Rainbow Three - MW] And Ian Carr on the trumpet, and his trumpet was electric and he could use a wah pedal to create a rhythmic effect, so half of the band was completely electric and the other half went through microphones, and I found I got the sound I wanted.

The second thing to raise Kaleidoscope to a higher level of accomplishment was the fact that a major label was involved, sympathetic to what Ardley was trying to achieve, and that Ardley was now working with a recording team able to hone his material and take it to the next level.

Gull Records boss, David Howells, puts it all into perspective:

Having had the pleasure of working in the 60s with Miles Davis, Thelonius Monk, Brubeck, Tony Oxley, Ray Russell, Howard Riley, fortunately been able to produce some of those records and what we were doing at CBS both in America and Britain, the trademark of that company was really superb, superb audio quality. They had the best engineers in New York, and we had great engineers in London, we had great producers. And so coming from that background, as I say, we set a very high bar for the audio aspect of everything we did in music… It was really how do we best represent the artist? And it has to be through the audio.

Engineer Martin Levan:

To me, producing, engineering, it is a creative art. It’s not just a technical game at all. I mean, technique does come into it, but I don’t really treat it as that. And very early on, in fact, what sort of kicked me off, when I first started in 1971, I was working with a fantastic engineer called Robin Black at Morgan, and he did the Jethro Tull albums, Cat Stevens, all sorts of fantastic stuff. I did quite a few sessions with Robin, and it must have been after about, I don’t know, six weeks being there as a tea boy and tape-op. I was on a session with him one day and I was watching him mixing and I said, Robin, I’ve got all this now. I’ve got it all together, but I was a kid, remember? I was just a child, you know, I said I’ve got this all together: it comes in through the microphone, mic preamp, through the EQ speakers out there [the speakers]. But then I see you lean forward and you turn the EQ knobs this way or that way. What tells you which way to turn it? And he just looked at me a bit puzzled, and says, ‘I’ll just turn it till I like it’. And that stuck with me. That was very early on in my career and stuck with me right the way through. I know engineers that reference other things, they kind of work to a formula, [and] I’ve never done that. I managed to find a way early on to do it how it felt good to me. And that’s all it is, it comes from the heart, any place it comes from. It’s expressive for me. And I think you talk about a certain style or a certain sound, it’s not just because of me, but it’s largely because of me, because I did it that way.

THE MUSIC

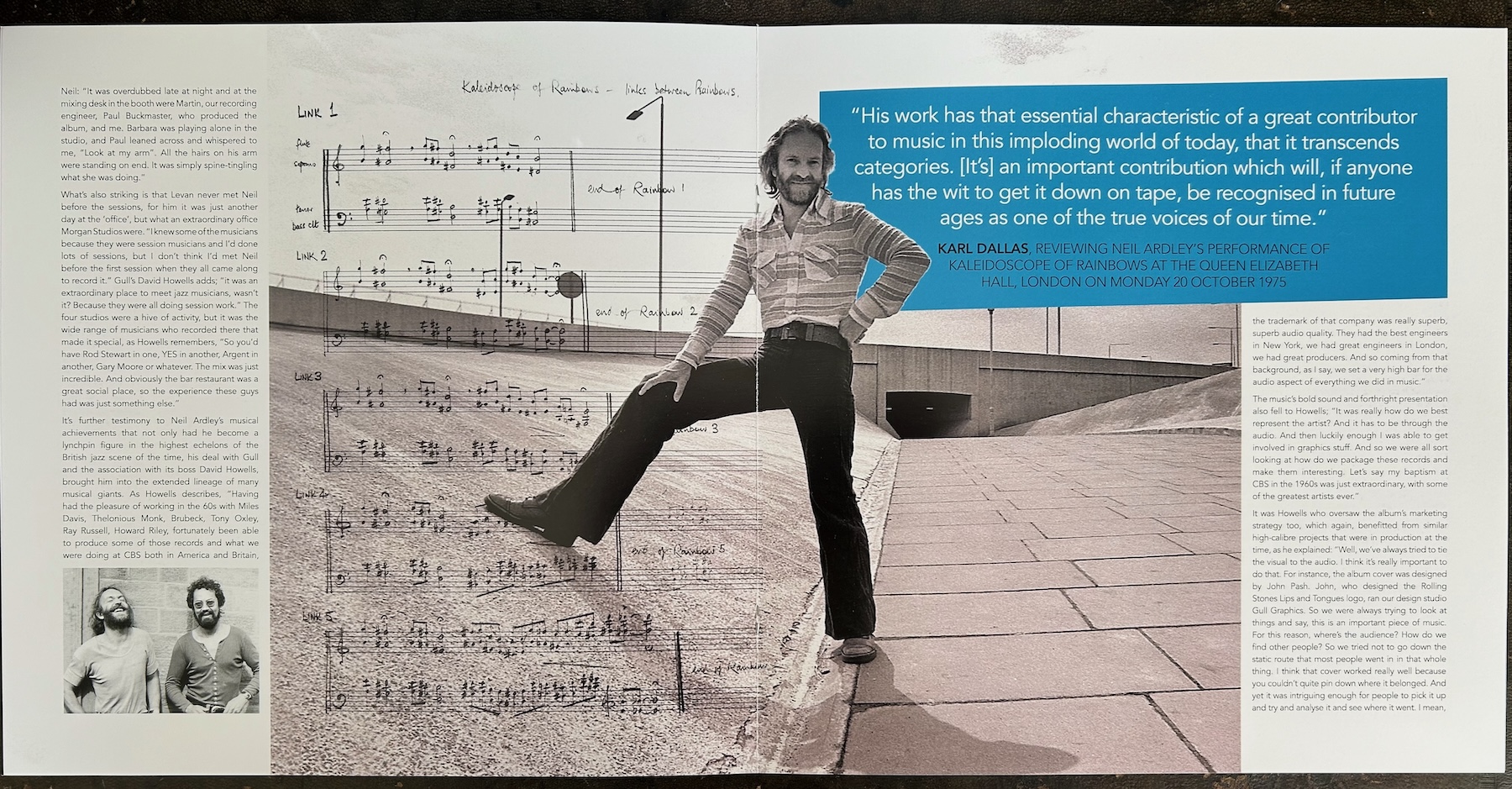

Poster for the live performance at the Queen Elizabeth Hall on October 20th, 1975 (used with permission of Ardley Estate)

Poster for the live performance at the Queen Elizabeth Hall on October 20th, 1975 (used with permission of Ardley Estate)

Listening to Kaleidoscope of Rainbows remains as engaging today as when I first heard it back in 1976, and every time that I’ve listened to it over the years in-between. It is immaculately conceived and executed, and very much not simply a recording - more a living organism that is straining at the leash, always on the edge of evolving once more. It remains a thrilling listen, and one that is also constantly revealing new layers and facets.

It is the perfect record not just for jazzheads, for rockers, for classical buffs wanting to try something new - but for anyone who digs the idea of music that brings the best of all three musical galaxies together into a sparkling new constellation.

That opening synthesizer “sunrise” - throbbing, incandescent - sets the scene for the procession of instruments that announce themselves, entering the musical ark one by one. The single beam of white musical light refracts into the various rainbows the musicians explore over the next 50 minutes.

Now, with the vantage point of being able to look back over fifty years of music, one can also appreciate just how forward-looking the work is, and how modern it remains. You will keep hearing things that sound like they were written or played just recently (like the many gestures we might think of as part of modern or even 20 or 30-year-old minimalism), and then you will have to remind yourself this stuff is actually 50 years old!

Remember also that the 1970s was a time when classical music had fully disappeared down the blind alley of serialism and atonality, where anything that smacked of “a good tune” was considered highly suspect. Jazz was likewise fully onboard with its equivalent, so-called “free jazz” movement that was alienating many of its more conservative listeners. And then there was prog rock which was disappearing up its own derrière with its increasingly self-indulgent noodlings.

Yet here comes a "serious" piece that dares to relish good tunes, brevity (!!) and even funkiness; a piece that dares to fully embrace an occasional rocky as well as jazzy vibe - in other words music that dares to be liked while it stretches boundaries.

Kaleidoscope has never lost that sense of being both experimental and accessible, and has never sounded dated. Even those synthesizers - so often the musical “tell” that immediately places a record in a particular era - manage to be timeless in the way that all the non-electronic instruments are. In so many ways Kaleidoscope pointed a way forward for composers and musicians struggling to find a mode of musical expression that people actually wanted to listen to, in which tonality and melody returned, in which genres were crossed, and yet anything was also possible.

When you think of the music scene today, in which anything is indeed possible but so little is genuinely achieved - with the result that much of what passes for quality and originality merely sounds like regurgitated leftovers from a superior meal of yesteryear - Kaleidoscope of Rainbows still sounds like something of a miracle.

Hallelujah!

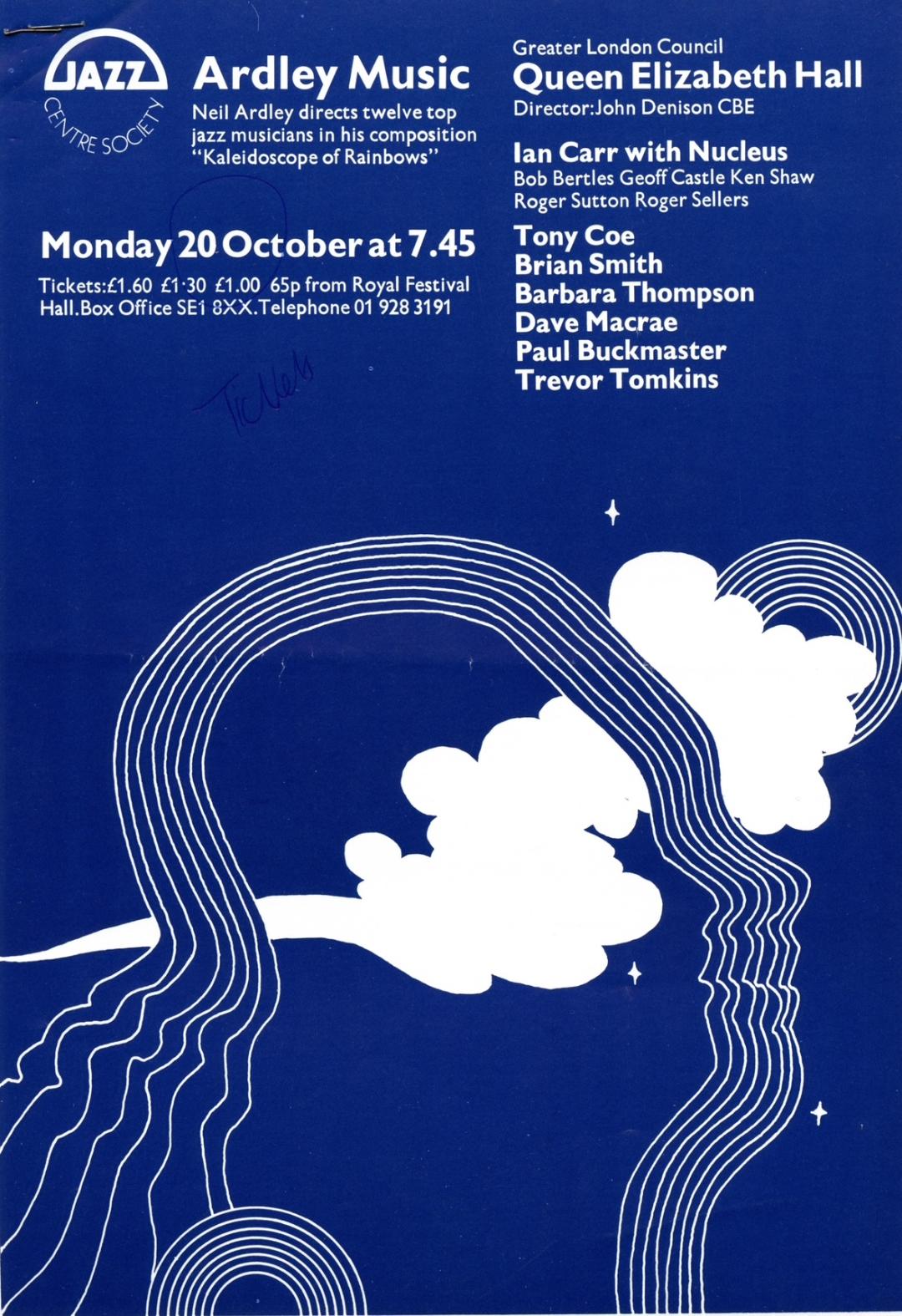

Neil Ardley with Ian Carr (by permission of the Ardley Estate)

Neil Ardley with Ian Carr (by permission of the Ardley Estate)

REMASTERING PERFECTION

Analogue October Reissue: 2lps in a single pocket, high gloss sleeve, with accompanying booklet (not shown is heavy duty outer sleeve, with re-attachable tab)

Analogue October Reissue: 2lps in a single pocket, high gloss sleeve, with accompanying booklet (not shown is heavy duty outer sleeve, with re-attachable tab)

So this was always a fantastic sounding record: dynamic, lifelike, room filling. Producer Paul Buckmaster and engineer Marin Levan managed to capture this incredibly varied group of instrumental colours both as individuals and as a collective in a manner which is clear but also rich; instrumental timbres emerge from - and disappear into - the collective seamlessly. Considering that most of the proceedings were captured ‘live’ with minimal overdubs and punch-ins, this is an incredible accomplishment.

The overall sonic palette is, literally, kaleidoscopic - conveying aurally that sense of a single beam of white musical light being refracted into a vivid rainbow of different musical colors. And it is all captured in that same organic analogue yumminess that characterizes the best rock and jazz records of the 1970s. Lovers of the Elton John and David Bowie sound of this period - for me a pinnacle of rock sonics - will find themselves in familiar territory. (Remember Buckmaster worked with both artists during this time).

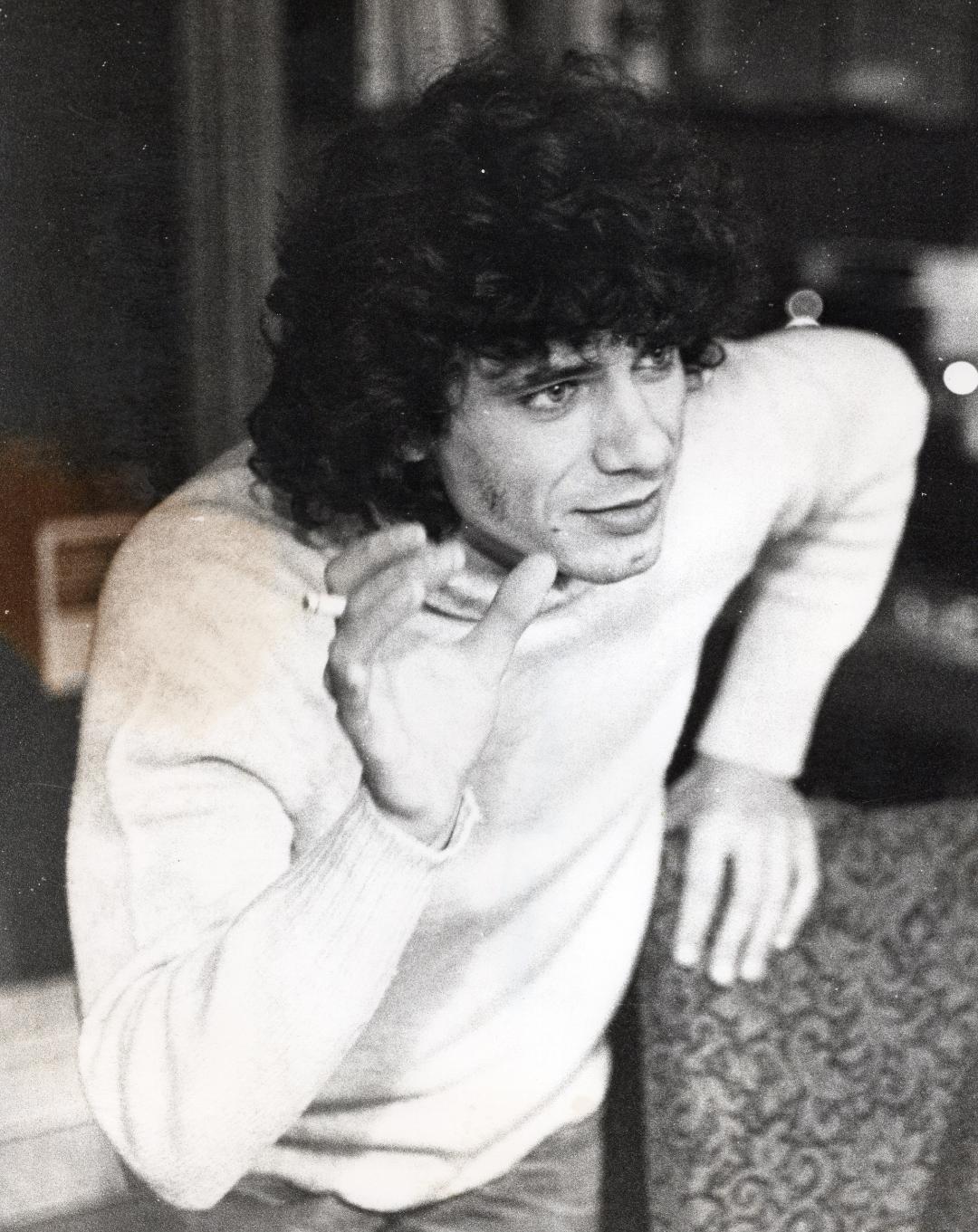

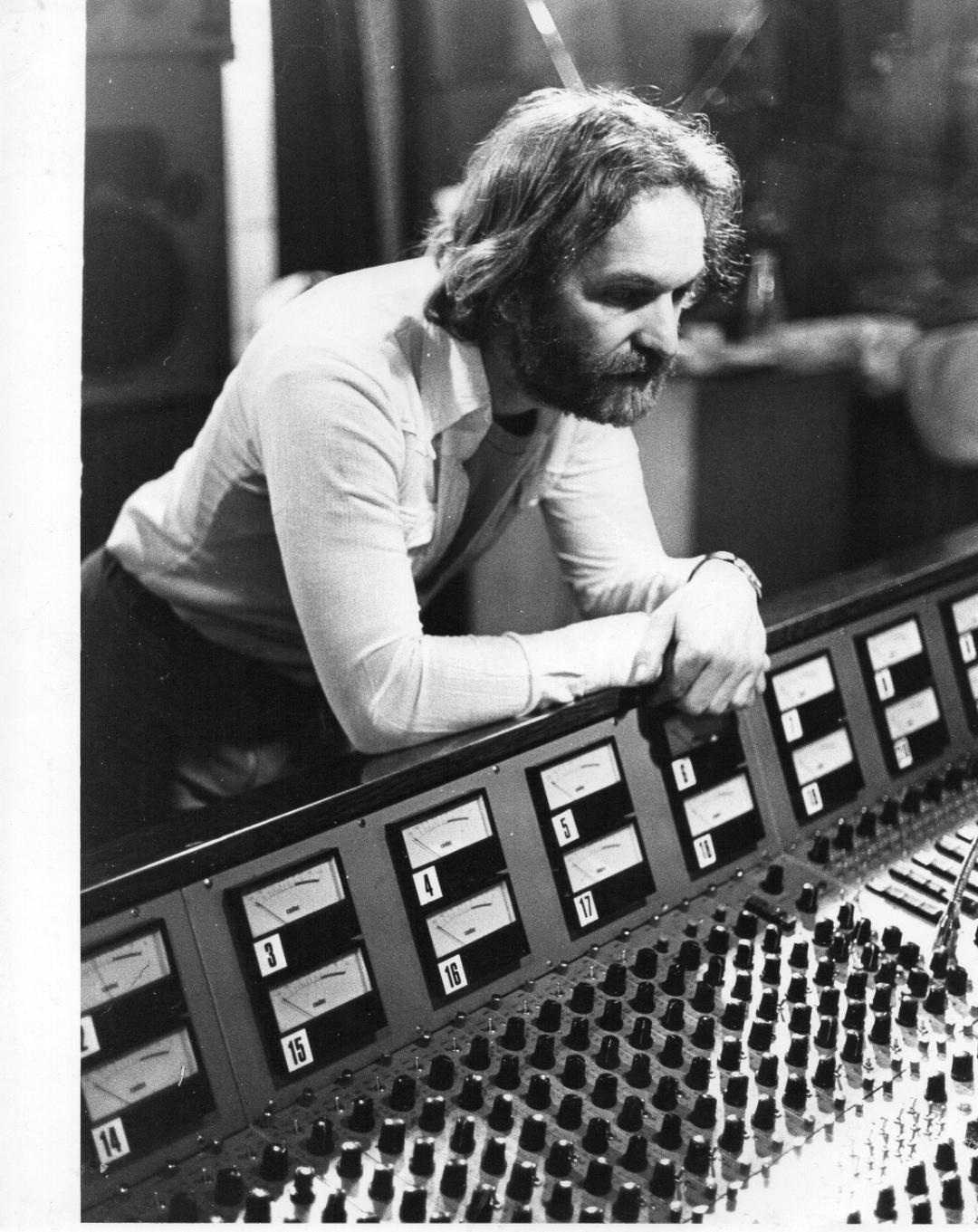

Producer and 'cellist Paul Buckmaster (by permission of Ardley Estate)

Producer and 'cellist Paul Buckmaster (by permission of Ardley Estate)

So, in all honesty, I was wondering how any reissue could improve upon the original beyond maybe cleaning things up a little and adding a little more sonic oomph. (After all, the Pure Pleasure double vinyl reissue of some years back had added nothing to the sonic virtues of the original single platter).

Boy, was I wrong!

I finished my audition of my still beautifully pressed and mastered UK original Gull pressing, marveling again at every aspect of this record, then dropped the needle on Side A of the reissue (which is cut at 33 across four sides). It took a while for my ears to adjust to a presentation that was feeling a little more upfront and detailed. I wasn’t immediately thinking “Oh, this is like Night and Day" or, indeed, "This is sounding different in a bad way". I was simply readjusting my aural view on the music.

Until we started getting into the intricacies of Rainbow 1, with its dense orchestration and crescendoing entries of instruments all leading up to a blistering trumpet solo by Ian Carr. The music is built over a repeating bass pattern analogous to the so-called ground bass that became a major feature of classical music beginning in the Renaissance period. Everything is framed within various articulations of the note and harmonic sequences of the Balinese scales upon which Ardley has built the entire musical edifice.

(N.B. All YouTube videos are derived from earlier digital sources, and in no way represent the sonics of the vinyl remaster being reviewed here. They are intended merely to give a sense of the music under discussion).

This is a gripping opening to the piece, driven onwards by the always lightly swinging but forthright bass of Roger Sutton, and the kinetic drumming of Roger Sellers.

You know how it is when you are listening to a piece of jazz or rock and there are those moments where the music is building and suddenly the drums switch gears and gather the whole ensemble together into a tight tutti which launches you in a new direction, and it just makes your pulse race and your heart sing? That’s what happens here - over and over - and it never ceases to get me going.

But now, in this new remastering, there’s just more of everything: the bass, the drums, the differentiation between the densely packed instruments - conveying each instrument’s full sonic character as an individual, but never sacrificing the sense of a live ensemble working together in galvanizing lockstep. I was listening deeper into the music than ever before. And even though the original offers up a pretty wide bandwidth, the relative lack of compression of the remaster, combined with the fact that the music is now spread to four sides (though still at 33) means that there is simply more real estate for the cut to breathe and expand within the grooves.

However, once the pyrotechnics of Rainbow 1 subsided into the relative calm of Rainbow 2, the virtues of the remaster really began to make themselves known. I started to fully appreciate how much deeper the bass goes - and how magnificently its tone has expanded. The bass is almost the most important player here (as it is in Harmony of the Spheres), providing both the through-line for the ear to latch onto, as well as both the structural and aural bedrock for the intricacies of what is going on above it, and this remaster has allowed the bass to expand in every direction, while also giving it extra precision and placement within the soundstage. My listening notes read: “This bass is cosmic!!!” For this alone, going back to the OG or, especially, the Pure Pleasure (which manages to generalize the bass so that it is smeared all over the sonic picture) became an exercise in unnecessary sonic compromise.

Rainbow 2 builds upon a plaintive flute melody (another Ardley ear-worm) and as the other varied wind and brass instruments joined in, together with delicate keyboard and percussion filigrees, the remaster delivered a timbral range and beauty that is simply breathtaking. I could also hear how the soundstage has expanded effortlessly beyond that of the original. Oh man, this is such beautiful music, and again I found myself marveling at how the improvised and composed elements meld together seamlessly.

Flip to Side 2 of the reissue and you’re in for One Funky Ride, as drums and a deliciously groovy bass launch Rainbow 3 - and Paul Buckmaster gets his moment in the sun with electric ‘cello gettin’ down, man, gettin’ down!

Alongside the remastered bass going deeper than I’d ever heard it go before, I could now hear all the very subtle but distinct timbral differences that made the electric ‘cello sing in a manner so different from its acoustic version, including the tonal shifts as Buckmaster moved from his G to D to A strings. Wow!

Rainbow 4 kicks off with wind and brass chatter, backed by percolating percussion and synths - all instruments given more body and timbral definition and substance in the remastering - melting into a muted trumpet solo by Carr (with distinct Miles overtones), then joined by saxes and ‘cello. This gives way to an exquisite solo by Barbara Thompson on soprano sax over a bed of shifting keyboard, guitar and wind textures that is utterly beguiling. Again, there is just more of everything delivered by the remaster. Listening to this is like sinking into a bed of gently lapping molten chocolate and whipped cream (or whatever is your dessert and/or sensual poison).

Barbara Thompson (by permission of the Neil Ardley Estate)

Barbara Thompson (by permission of the Neil Ardley Estate)

Thus concluded the original Side A of Kaleidoscope and, like Tubular Bells, it is such a colorful and compelling progression of musical originality that it has tended to overshadow the achievements of side B. Not so in this remastering, which I feel allows the less immediately attention grabbing charms of Rainbows 5 through 7 and the Epilogue to register more fully. This was when I really started to appreciate the felicities of this remastering over the already excellent OG: its increased sonic richness, its enhancement of individual instrumental timbres within a more defined and open soundstage, its greater dynamism and heightened impact, its bringing out of more of the extraordinary layering and constantly shifting landscapes of Ardley’s orchestration, its greater headroom that removed any hint of sonic restraint. And I continued to marvel at that bass - always leading yet also gathering together the musical argument and the forces making it.

I’m not going to go through the remaining Rainbows in detail here, except to remark that you will be constantly surprised by the variety of sound and melodic invention on display. The way Ardley is constantly rearranging his instrumental groupings, has them playing with each other, then setting each other into relief, is spellbinding. Literally from second to second there is something new for the ear to latch on to. Composed and improvised elements are constantly weaving in and out of each other in a manner that is so unique, and the way in which we move between classical and jazz and rock gestures and idioms is seamless. What we have here is a musical embodiment of Ovid’s endless variation of Metamorphoses.

The final Epilogue then slowly gathers up all the disparate musical elements into a giant reprise which seriously gains in impact and definition on the remaster, benefiting enormously in terms of dynamic impact and lack of congestion by not being forced into the end of a long 33rpm side, but spread over a shorter one.

The end now feels even more like the necessary climax it actually is to an epic, winding journey, with everything now in its proper place. All the divergent strands which sprang from the Prologue’s opening synth fanfare now return to a fortissimo final series of chords: the rainbow once more a single beam of incandescent white light.

ACHIEVING REMASTERED GLORY

Miles Showell a fan of Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy? (Photo by Analogue October Records)

Miles Showell a fan of Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy? (Photo by Analogue October Records)

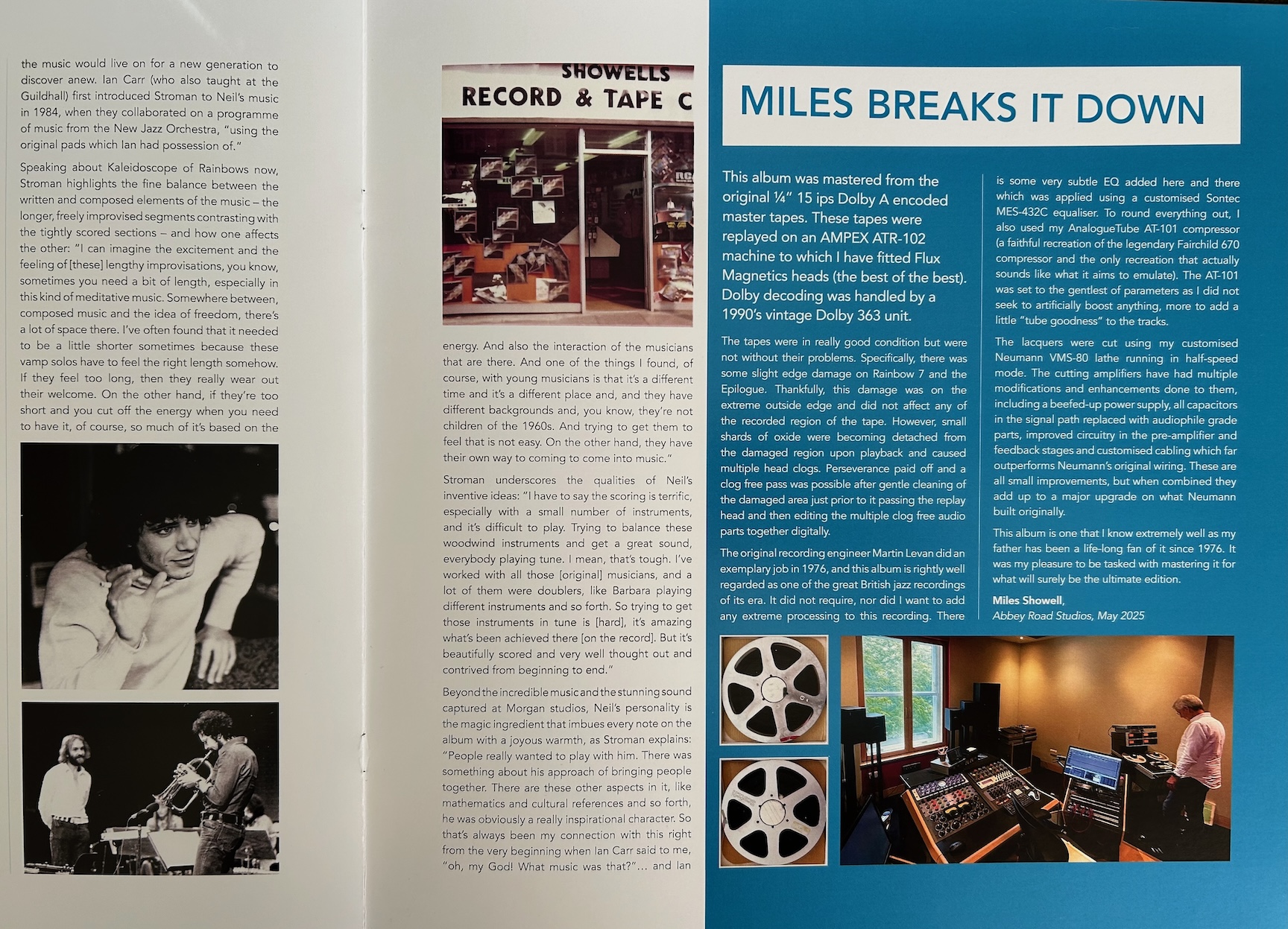

Those of you retaining some degree of prejudice towards vinyl reissues of analogue recordings mastered via a digital file (albeit of the original master tape), or towards the mastering skills of Miles Showell at Abbey Road Studios, or indeed of half-speed mastering, may have a hard time accepting that all the sonic excellence of this reissue is the product of all three of these elements being part of the process.

I would have shared your skepticism until I heard these results. Thus far I've not been the biggest fan of Miles Showell's work.

But on this one I'm changing my tune - Miles nailed it.

Going into this project, the founder and moving force behind Analogue October Records, Craig Crane, had intended to do an all-analogue mastering, as he had done with Harmony of the Spheres. But the passage of time and the resulting inevitability of certain chemical interactions forced a change in plans…

Craig Crane:

So, these tapes are 50 years old. Last run in the early 2000’s at Metropolis (ironically, by Miles, for the Dusk Fire CD release). They were starting to show their age.

But by default, Miles’s Half-Speed Mastering process has that digital step in it (capture), before he does anything. Now, granted, we could have gone tape to lathe. That’s always an option. But when we first listened to the tapes, something was off. I heard it, as did Miles. Tiny variations in azimuth / phase alignment. Reason? Unknown. But it was there. We also noted some slight debris after the first listen.

Miles, being the perfectionist, asked me if I had any objection to a digital capture, one track at a time to address any micro issues? I knew this approach would add some time to the process, but would also be for the betterment of the music and the end user.

So that’s what we did.

Prologue captured, then Rainbow 1 and on we went, with Miles keeping one eye on the tape and the other on the phase meter. His tape machine in his L room uses his own new custom heads from New York, kept under lock and key when he’s not there… He knows that room, inside and out. To be fair, it’s a stunning room.

I digress… Each track was captured to his 192/24 spec, and any mechanical adjustments made on a track by track basis. We are not talking big adjustments. These were macro adjustments… an Ant’s fart would be more obvious… but we got forensic.

Don’t forget, a year prior, I’m standing at Neil’s resting place in the Peak District, making a promise to a man I’d never met, that I’d “do him proud”… so making these critical decisions are all a part of that promise.

You can read more about the specific technical detail and equipment used by Showell in his dedicated essay included in the accompanying booklet.

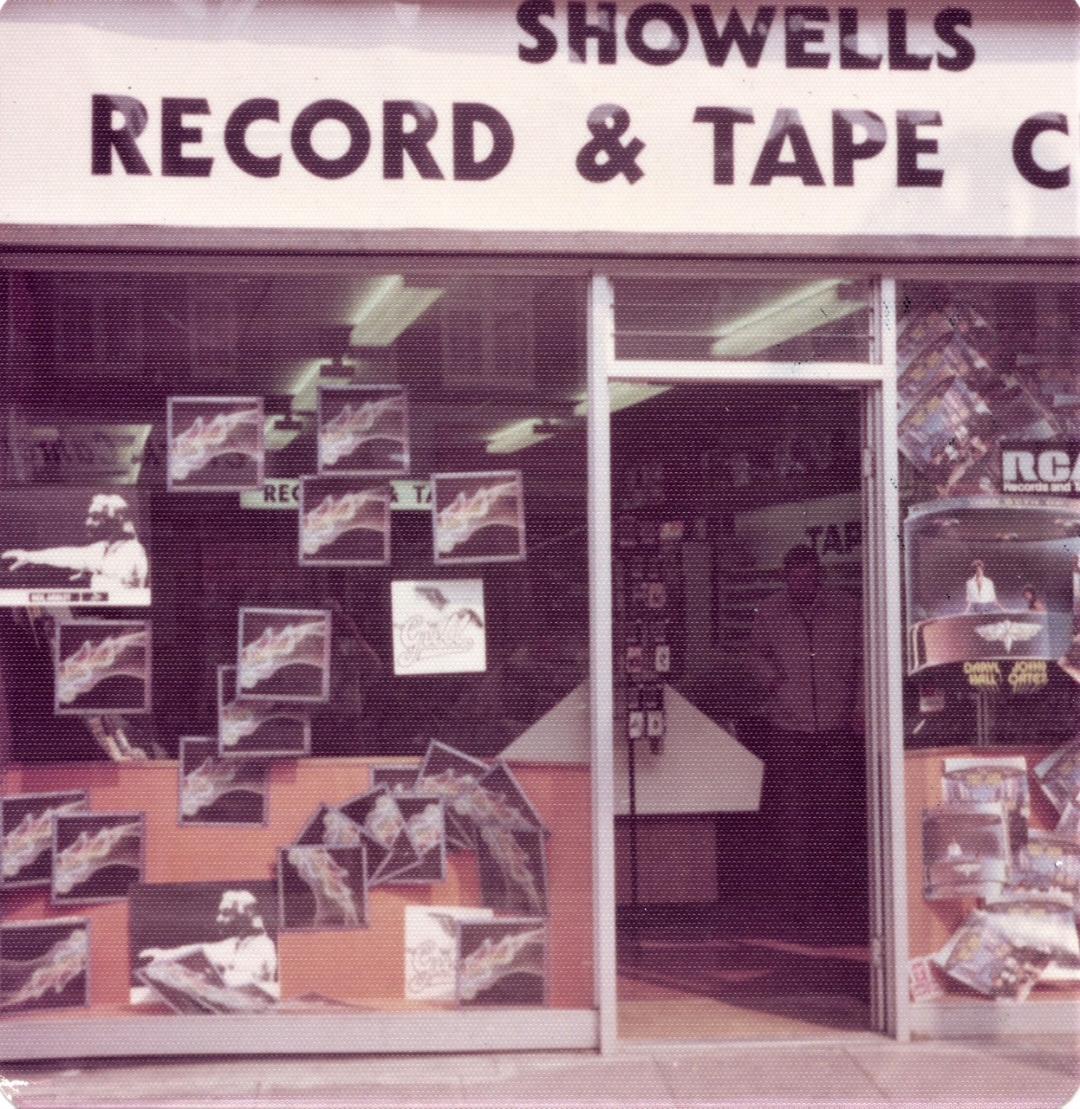

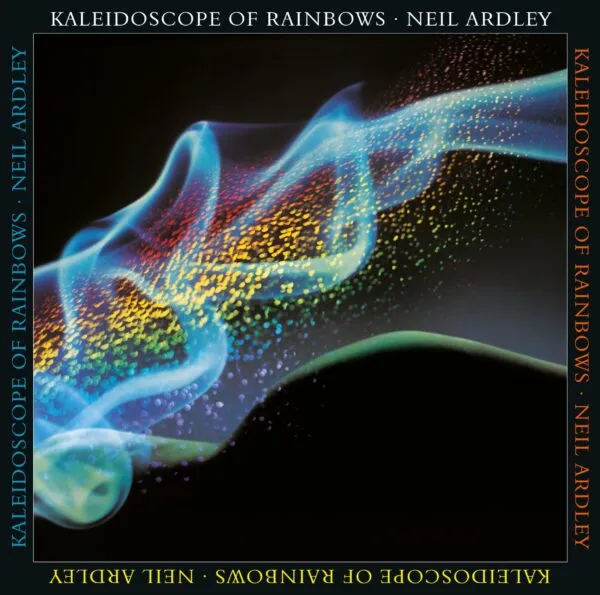

There’s actually an intriguing personal connection between Miles Showell and this record. His father Brian owned a record store in West Wickham, Kent, and was so taken with the album’s striking cover design (by John Pasch, creator of the Rolling Stones’ iconic tongue-and-lips logo), and the music contained within, that he created a full window display that included multiple suspended copies of the album and photos of Ardley.

1976 window display for Kaleidoscope of Rainbows at Brian Showell's record store (by permission of Neil Ardley Estate).

1976 window display for Kaleidoscope of Rainbows at Brian Showell's record store (by permission of Neil Ardley Estate).

Brian Showell:

I then played the LP non-stop in the shop, and managed to sell it to many unsuspecting customers. Neil got to hear about this unlikely shop and came down with his camera to see for himself. After the shop closed at the end of the day we spent an enjoyable hour at the local pub and he came back to my home for a meal with the family.

Subsequently becoming friends, Brian and his son Miles went to hear a playback of Ardley’s next album, Harmony of the Spheres, before its release.

So it’s hardly surprising to read Miles Showell’s conclusion to his booklet essay:

“This album is one that I know extremely well as my father has been a life-long fan of it since 1976. It was my pleasure to be tasked with mastering it for what will surely be the ultimate edition.”

Brian Showell sitting in on his son's mastering session for KOR at Abbey Road Studios (photo by David Howells)

Brian Showell sitting in on his son's mastering session for KOR at Abbey Road Studios (photo by David Howells)

With immaculate slabs of vinyl pressed at Record Industry at Haarlem in the Netherlands, top-of-the line packaging, “labour of love” screaming from every corner of this deluxe physical and aural presentation, ultimate edition it is.

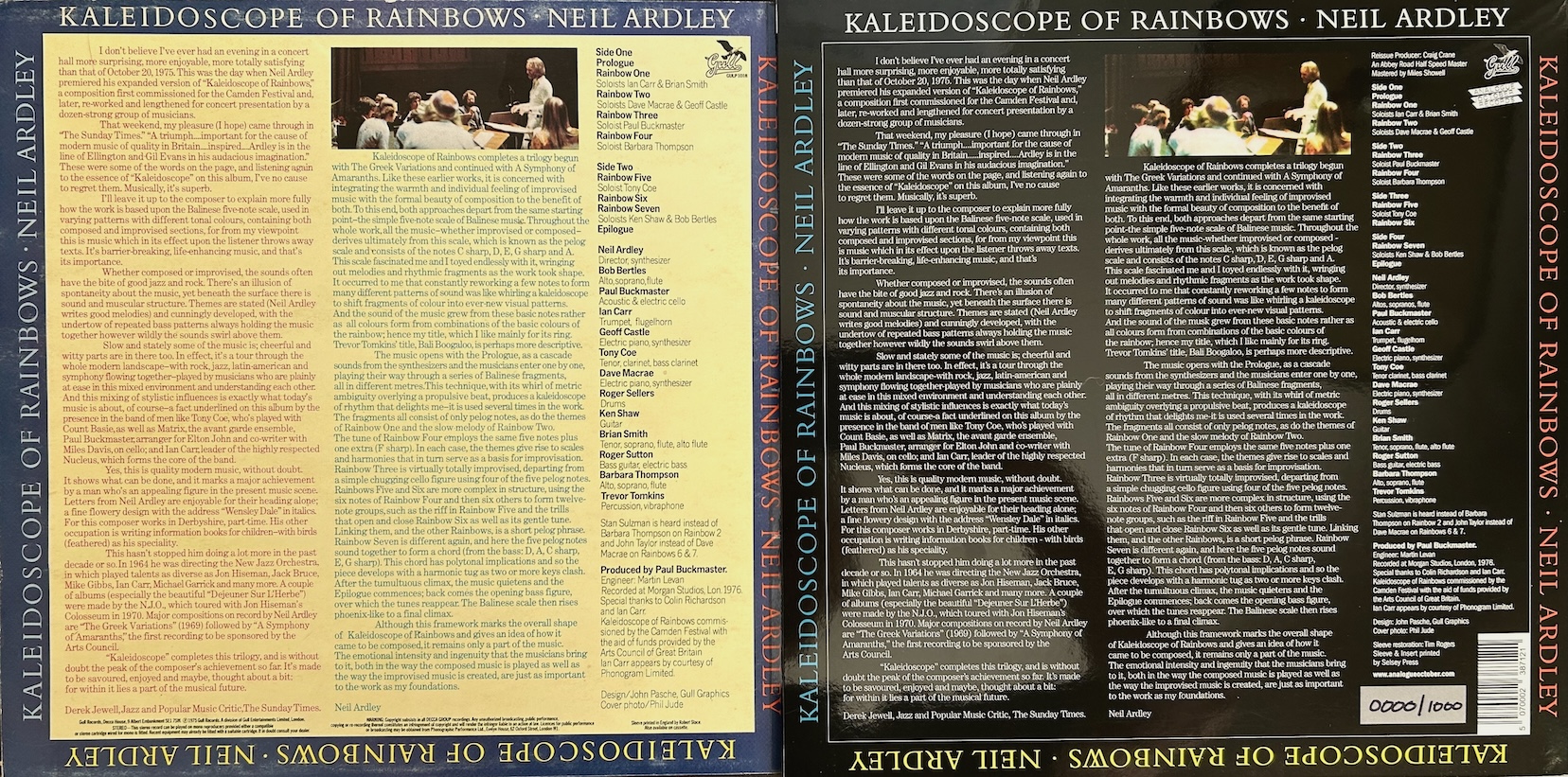

Back covers of the original UK Gull pressing (l.) alongside the Analogue October reissue (r.) Note the change in color scheme for the reissue, which is also presented in a higher gloss finish. Purists will object; I like the more opulent "feel" of the reissue.

Back covers of the original UK Gull pressing (l.) alongside the Analogue October reissue (r.) Note the change in color scheme for the reissue, which is also presented in a higher gloss finish. Purists will object; I like the more opulent "feel" of the reissue.

IN CONCLUSION...

“Somewhere between composed music and the idea of freedom, there’s a lot of space there…”

(Scott Stroman, Professor of Jazz at Guildhall School of Music and Drama, London, custodian of Neil Ardley’s Archive)

Since the earliest days of Western classical music, exploring the space between composed and improvised music has been the engine driving forward musical expression and invention. From troubadours extemporizing vocal flourishes to impress the objects of their affection, to Baroque musicians embellishing their scores’ written notes with all manner of increasingly complex ornamentation, the classical tradition always placed greater stock on the composed score, while nevertheless accommodating, even encouraging, its practitioners’ flights of fancy. That all changed with the advent of jazz, where improvisation took over as the dominant impulse, driving the form onward like a train engine jumping the tracks, growing wings and taking flight. With the arrival of rock things loosened up yet again, in a different though often less disciplined way.

The brilliant uniqueness of Neil Ardley lay in his ability to perfectly marry the divergent needs of formal composition and free improvisation, to create an extended framework within which the seemingly contradictory imperatives and modalities of classical, jazz and rock not only work together in perfect synchronization but feed off each other to create something vital and new.

And to attract the top musicians in England at the time to pull it all off - both in concert and in the studio.

The results as caught on this remarkable record make my heart race, my pulse quicken, and my brain light up in all the right places, and I’m guessing yours will too. (Playing this record brought my wife downstairs to sit in on the listening session; she rarely does that for anything other than for Bowie and other 70s rockers). If my ears could twitch like my cat sensing a fluttering bird (and potential prey) nearby, a-twitching they would go!

To listen to Kaleidoscope of Rainbows is to be reminded that art is often at its most liberated best when it is most disciplined, yet also daring to think differently; to proceed from its inherited constraints, custom and expectations; but then to think outside the box while working within it.

Then sit back and watch while people’s minds are blown!

This is music that I dare anyone not to be thoroughly engaged with. Hell, those ear worm tunes and the bass grooves and that propulsive drumming that shimmers, kicks and darts, then locks in - all of that alone will grab you and not let go! Let alone the verve and off-the-chart virtuosity of all those top musicians getting down and getting off on the whole enterprise. Their joy is palpable - and it is very much communicated. I've said it before and I'll say it again - this is such a fun listen!

Yup! This music is as exhilarating to listen to now as when I first heard it on the radio fifty years ago, lying on the floor of my bedroom, kaleidoscopes of musical rainbows dancing between my ears. I couldn’t believe anyone made music quite like this. (They didn’t, and they still don’t - Ardley is a one-off as far as I am concerned).

And in this new vinyl incarnation (limited to 1000 copies, so do not tarry), the sonic journey of Kaleidoscope is substantially enriched for a new generation to discover what authentically original music sounds like, rather than music that is merely going through the paces of being original, the 'original' that current trends define as “cool”, but which wears thin and disappears within a few short years (hell, a few short months!) - leaving behind vapid noodling over vails of emptiness: the curse of our oversaturated but undernourished modern "culture".

No, Kaleidoscope of Rainbows is that rare thing - a timeless, true original. A classic that still sounds revolutionary fifty years on.

And is definitely one for the ages.

EPILOGUE

Kaleidoscope of Rainbows live at the Chichester Festival Theater in 2025 (photo by Analogue October Records)

Kaleidoscope of Rainbows live at the Chichester Festival Theater in 2025 (photo by Analogue October Records)

Craig Crane:

The only live show launch for a reissue???

50 years after KOR was performed at the Queen Elizabeth Halls, we put on two live shows with the Guildhall Jazz Orchestra with Binker Golding as guest soloist under the leadership of my good friend Scott Stroman.

Chichester Festival Theater and then the following night at the Barbican for the EFG London Jazz Festival.

Kaleidoscope of Rainbows live at the Barbican, London 2025 (Photo by Analogue October Records)

Kaleidoscope of Rainbows live at the Barbican, London 2025 (Photo by Analogue October Records)

In attendance:

Viv Ardley (Neil's widow)

Ana Gracey (Barbara Thompson’s daughter)

Martin Levan (original engineer at Morgan)

Miles and Brian Showell

And what better way to get each show started that the extended prologue from the original sessions, with studio chit chat from Neil himself as he tweaks and noodles on the synth before going for a take, with Viv Ardley being handed the control for the Revox to have Neil then start the show, posthumously.

I won’t lie… I was an emotional wreck!

Neil Ardley (by permission of the Ardley Estate)

Craig Crane, owner of Analogue October Records, listening to playback at Abbey Road (Photo by David Howells).

Craig Crane, owner of Analogue October Records, listening to playback at Abbey Road (Photo by David Howells).

Analogue October Records is one of the growing number of smaller reissue labels which, by prioritizing premium mastering from original sources and extensive accompanying materials, all presented in imaginative, beautifully designed deluxe packaging, are producing some of the most desirable records out there. AOR is the passion project of Craig Crane, who is based in the medieval cathedral town of Chichester near the south coast of England. Chichester is also home to the world-renowned Chichester Festival Theater, founded in 1962 with Laurence Olivier as its first Artistic Director. If you ever get a chance to visit, and hear its superb choir in one of the UK’s oldest cathedrals, do so. Growing up as a teenager I lived some 45 minutes away, and I always try to take in a show at the theater if I return to my old stomping grounds.

I spoke to Craig for my review last year of Neil Ardley’s Harmony of the Spheres, but as his label grows and enters a new phase, I wanted to see what was cooking as we head into 2026. I caught up with him via email...

The one big question I would like you to get into is what the future holds. Talk about the experience of getting the label this far, what the next steps are, the challenges for a small label like yourself, how best to move forward.

That’s the big question, isn’t it? Well, I’ve already decided that the label is where my real energy is. Therefore the shop from which it was launched is now for sale.

3 titles released. 6 titles cut, a 7th (new material from Henry Lowther and then London Jazz Orchestra) has been recorded and I’ve been asked to bring it to market by Henry himself. 8,9&10 should cross the finish line late this summer (as a box set!)… and the one thing I know I do need is investment that matches my energy and drive. I’m working on that too.

I’ve worn many hats… I was a Puppeteer (Hensons, Spitting Image etc.) for many years, before moving into CG and VFX for Marvel, Disney and Warners… a sharp and debilitating burnout saw me step back and open a shop, now in its 9th year… and of course, the label, quite literally born in the pandemic.

It’s not easy. It’s not for the faint hearted. It’s bloody expensive. But damn, it’s fun, even when it’s not!

Nothing ruins your day more than a bad test pressing of an awesome cut. That’s why I changed pressing plant mid-project on KOR.

I needed a plant that did test pressings on the spec vinyl for the release, not Bio Vinyl. So just making that change adds 1000 bucks to the budget. But what I got at Record Industry (Anouk and Ton have been awesome) was a TP that allowed me to really hear the cut. Well, in this case….. cuts, because Miles (Showell) and I went a few rounds on this. Because, you know…. I am only interested in the BEST something can be. I think Anouk summed it up best… “I get the feeling you’re quite ‘particular!’” But she’s right. You have to be. You are asking people to spend some dollars on a tangible asset. Why buy this record over that record? I can buy two average records for the price of this one record! So it HAS to land as intended. Definitive.

So that’s the road map.

I’ll flit between Gearbox and Abbey Road for mastering on a case by case basis. I love both Caspar [Sutton-Jones, who mastered Harmony of the Spheres] and Miles. Both bring their A game to the room. I try to bring mine. And with Mike Flynn of Jazzwise supporting me with his deep research and essays, and my local village printers killing it on the printed materials and Record Industry also being somewhat “particular”, I feel that of all the hats I’ve worn, this one feels very made to measure.

At Abbey Road: (l. to r.) Brian Showell, David Howells (former head of Gull Records), Craig Crane and Miles Showell. (Photo: Analogue October Records)

At Abbey Road: (l. to r.) Brian Showell, David Howells (former head of Gull Records), Craig Crane and Miles Showell. (Photo: Analogue October Records)

And specifically the next titles are..?

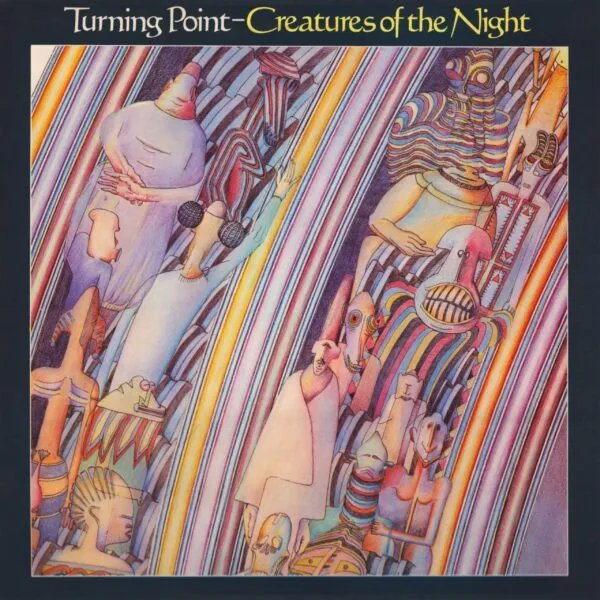

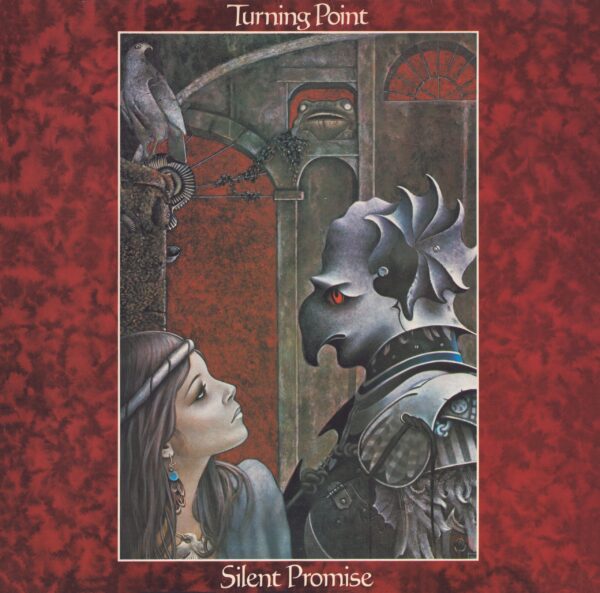

Two from Turning Point - the late 70s British jazz rock/fusion group built around ex-Isotope players, most associated with Jeff Clyne (bass) and Brian Miller (keys).

Lineup and identity:

• Jeff Clyne: bass, band anchor, also known from Isotope

• Brian Miller: keyboards, composer-arranger feel throughout

• Dave Tidball: sax, carries most lead melody and “voice” in the band

• Paul Robinson: drums, more groove-forward than showy

• Pepi Lemer: wordless vocals used as an instrument, a big differentiator versus similar UK fusion

Discography that matters - and the ones I am doing:

• Creatures of the Night (1977, Gull)

• Silent Promise (1978, Gull)

Compared with the more guitar-hero end of 70s fusion, Turning Point tends to:

• prioritize composed themes and ensemble blend

• put sax and keys up front, with bass as a strong melodic and rhythmic centre

• use Pepi Lemer’s vocal as texture, not “songs”, which gives it a slightly Canterbury-adjacent feel without becoming prog pastiche

I love these two records and the new cuts from Gearbox are beautiful. The essay is a knockout. I just have to bring it all together now!!!

Stay tuned - Analogue October Records is a label to watch… and listen to.

Available for purchase directly from Analogue October Records.

.png)