Resistance Music - Shostakovich from Berlin During Lockdown

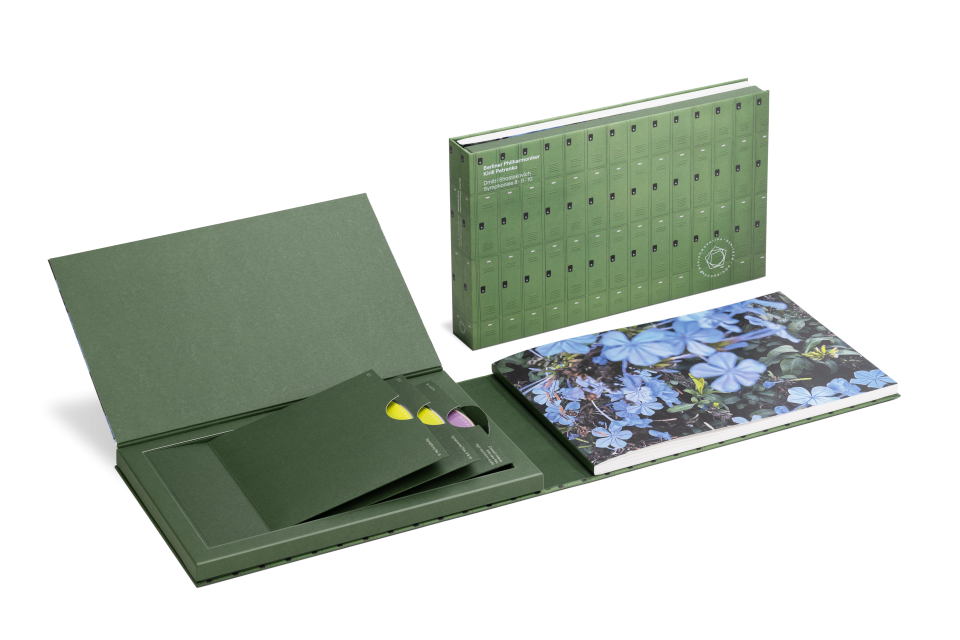

Music-Making of Searing Intensity on the Berlin Philharmonic’s In-House Label

It being the Season ’n all, it’s a little surprising to find myself writing not about carols and Messiahs, or even Nutcrackers (that’ll be next year, I hope).

Instead, owing to a need to clear up a backlog of reviews, I have found myself engaged with music of a far darker hue, beginning with Furtwängler’s recorded legacy from WWII, and now these three Shostakovich Symphonies, missives from behind the Iron Curtain, recorded during the cold war of the Pandemic.

But in other ways this is music utterly of the moment. The fall of the Assad regime in Syria has laid bare the terror imposed on that country’s citizenry for decades. Ukrainians continue to resist the land-grabbing whims of a tyrant, but are paying a devastatingly high price.. The Palestinians and Israelis continue their forever war. In Europe, Germany and France - pillars of the EU - are being roiled by political uncertainty and the rise of extremist parties on the right and left. Former democracies like Hungary have tilted inexorably towards totalitarianism. And here in the US, at least half the country faces the prospect of a new Presidency with some measure of trepidation, if not major anxiety. Everywhere people are dealing with the emotional toll of uncertainty, fear, disruption. And the challenge of how to find any hope in straightened circumstances.

These are the subjects of Shostakovich’s music, and it’s why his works speak with ever increasing resonance and clarity to today’s listeners who are, unfortunately, gaining more than glimpses of the kind of suffocating totalitarian environment in which he had to live daily for his entire life - and survive.

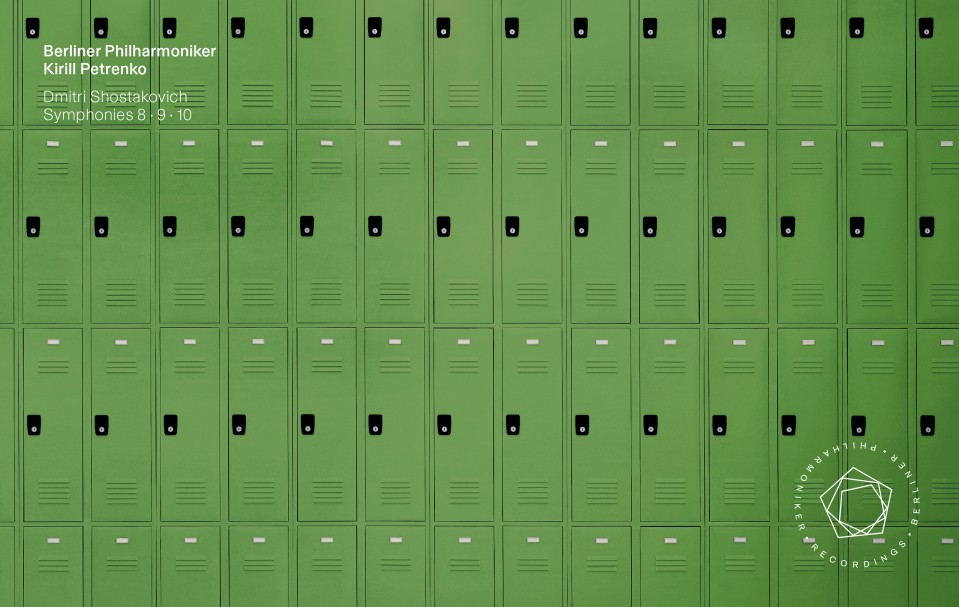

This set from the Berlin Philharmonic under its new Principal Conductor, Kirill Petrenko, immortalizes musical acts of survival in the face of anxiety, isolation, and fear - from the scores themselves, to the circumstances of these recordings.

You might just as well subtitle this set: “Humanity Strikes Back!”

The 8th Symphony, a dark cry of angst and terror from the heart of Russia during 1943, was recorded during a similarly dark night of the soul as the pandemic reasserted itself in November 2020, with orchestra members distanced from each other and no audience present (for broadcast solely via the BPO’s Digital Concert Hall). The 9th Symphony, a supposed “victory” symphony from 1945, which the composer turned into a combined elegy for the fallen and a mock-heroic satire of the very same empty (as he considered them) patriotic blandishments he was supposed to be propagating, was recorded a month earlier in October 2020, with minimal and socially distanced audience present. Only the 10th Symphony, composed after the death of Stalin in 1953, is given with full audience present, albeit masked. Since the work offers an ambiguous take on the potential for a loosening of personal and political freedoms in the wake of Stalin’s death, again the time of its recording in October 2021 mirrors the circumstances of the work’s composition - and its equivocal tone.

It’s hard to imagine better programming for the times as they were back then. As a result, this is a set that burns with a white hot intensity, especially in the 8th and 9th Symphonies.

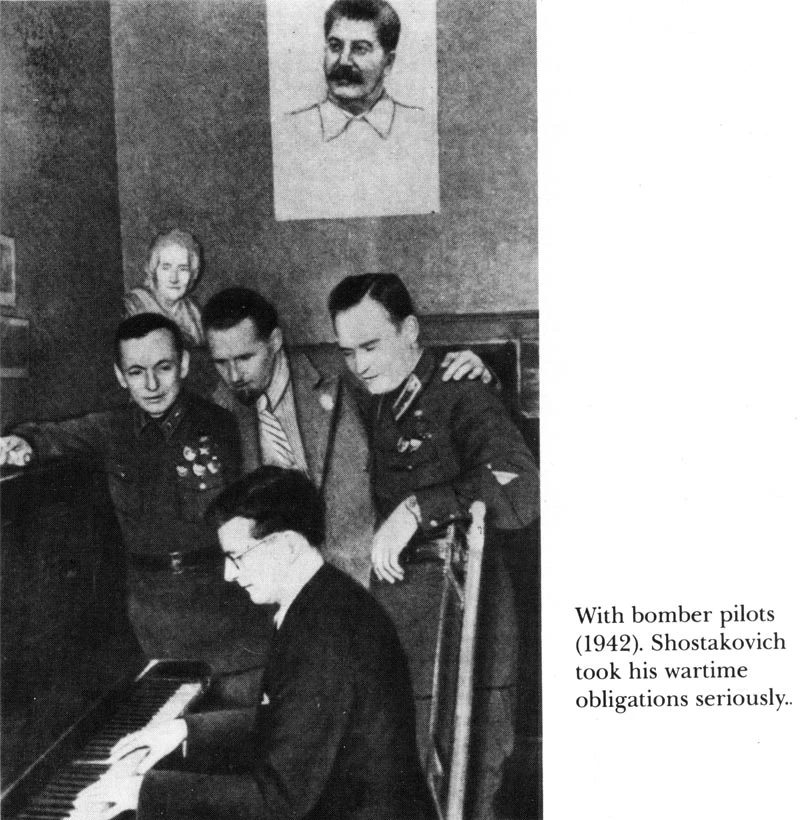

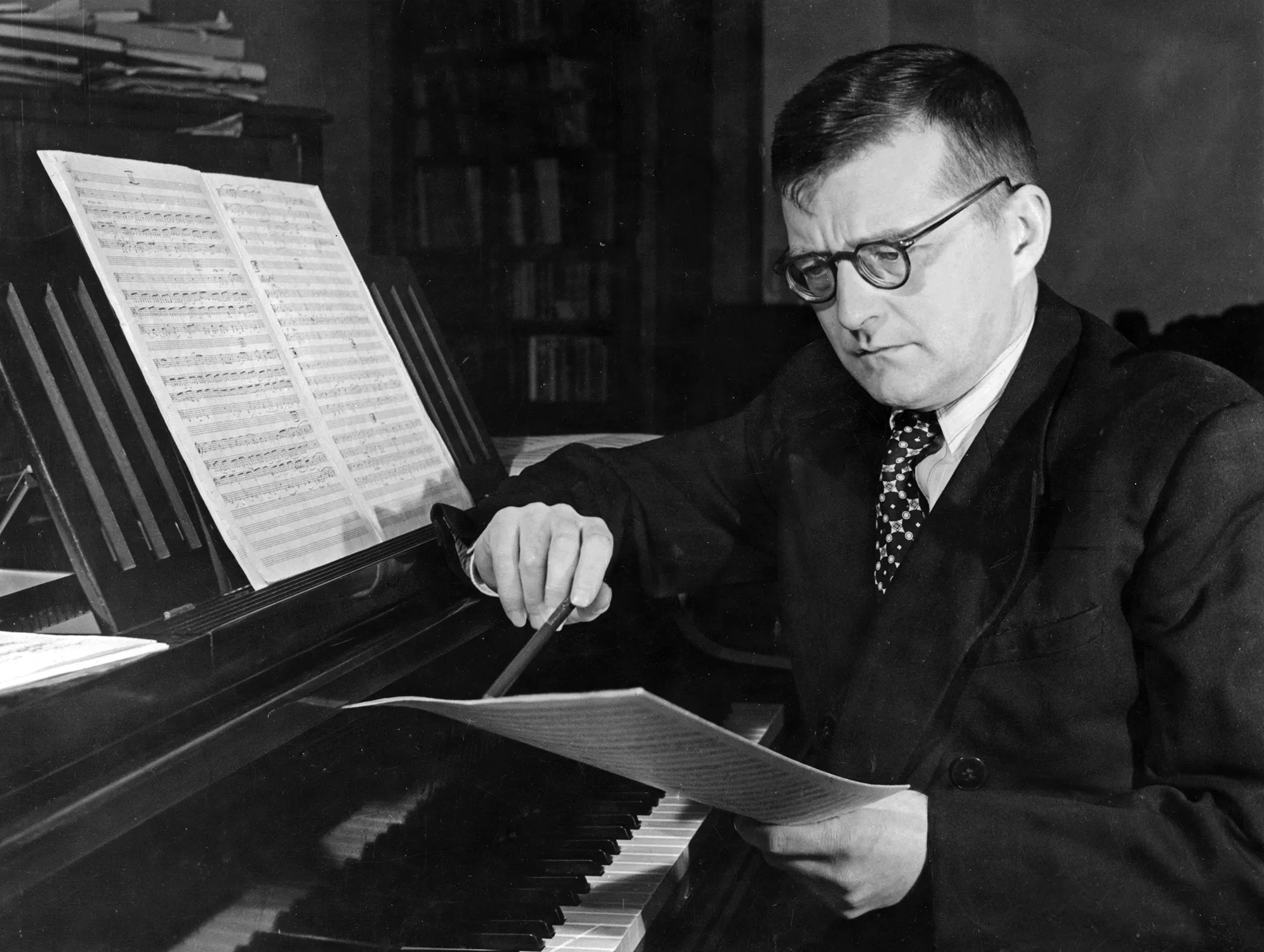

Dmitri Shostakovich in the 1940s (Photo: L.M. Dorensky)

Dmitri Shostakovich in the 1940s (Photo: L.M. Dorensky)

For the composer of these three symphonies, Dmitri Shostakovich, the mere act of writing music during the Stalinist era was a high wire act of incredible skill and daring. If he ever lost his balance, the plunge to certain death was assured. During his lifetime he was put on notice several times by the authorities that he needed to “modify” his artistic sensibilities to something closer to the Party Line.

At the time Shostakovich was working, Western classical music was consumed with an obsession with post-tonal idioms. This was the Age of the Modernists: Stockhausen, Boulez, John Cage, Xenakis, Berio… After the convulsions of the early 20th century, and the wholesale adoption of serialism, atonality, and aleatory methods, anyone like Shostakovich or Benjamin Britten or Aaron Copland who still wrote in traditional harmonic language and forms was considered old hat, irrelevant - even suspect.

As Pierre Boulez wrote in 1952: “Any musician who has not experienced - I do not say understood, but truly experienced - the necessity of dodecaphonic music is USELESS. For his whole work is irrelevant to the needs of his epoch”.

A mere half century later how that had all changed. Now it is those same self-appointed revolutionaries and “Guardians of the New” who are old hat, who are considered to have wandered up a blind alley. They are the ones considered something of a detour on the way to the main event. Traditional harmony is back in vogue (albeit spiced up with some of their modernist techniques).

Shostakovich himself gains in popular and critical stature with each passing year. His symphonies are recorded almost as often as Mahler’s, and share many qualities, not least their fraught emotional landscapes derived from their composers’ own psychological traumas.

Shostakovich, living through the darkest days of the Soviet Union in war time, coming hot on the heels of a “peacetime” era of domestic terror imposed by Stalin, used his music as a way of exploring and voicing his inner angst and resistance - both to the Nazis, and his own government. However, he always had to find a way to code his message, lest he hear the dreaded knock on the door in the middle of the night, and then be hauled off to the Gulag, never to be seen again, as happened with so many of his friends.

His music is resolutely bound up in the traumas and the upheavals of the 20th century, written in the furnace of resistance to domestic totalitarianism, and external invasion. It is always asking the question: “How do I live, let alone survive, when my life, my humanity, and everything I hold dear, are constantly under attack, and when my physical and mental freedom are in constant jeopardy?”

Each of these symphonies provides its own answer to that question. An answer that is never straightforward, but with many shadings. But an honest answer nonetheless.

At a time when the world is facing new perils and jeopardy, and the very real threat of greater instabilities to come, this is why Shostakovich’s music speaks to us so clearly right now.

And why it speaks so clearly in this set, a missive from the worldwide convulsion of the pandemic.

As the conductor Kirill Petrenko states in his Preface printed in the accompanying book:

“It may sound paradoxical, but performing these three symphonies in a period of almost total isolation took me personally to a new level of understanding this music. I experienced something I hadn’t discovered in these works before.”

Symphony No. 8 in C minor, Op. 65

The Eighth Symphony, composed in 1943, and coming hard on the huge “Leningrad” Symphony, which was written to mark the citizenry’s defiance of the Nazis (and, heavily disguised, the pre-War Stalin Terror), was ostensibly to be a work celebrating new Soviet victories in the War (like the Battle of Stalingrad), with a progression from dark to light.

At least that was the official expectation. But in the event the work feels far more weighted towards tragedy than victory, and is a searing baring of the composer’s soul at a time of huge stress. It is one of the supreme symphonic utterances of the 20th century, and seems to grow in stature with each passing decade. It is so hardwired into shared grief, anxiety, but also defiance, that it feels like it could have been written yesterday.

The triumph of the end of the “Leningrad” Symphony (hollow though it may be), is swept aside by the opening of the 8th in no uncertain fashion.

From the moment the turgid, and searing, opening of the 8th hits your ears, you will be riveted to your seat. The drama unfolds with all the urgency of a heart attack. Stabbing, growling figures on ‘cellos and double basses are joined by the higher strings in what could be both a wail and a cry of terror. This hearkens back to the assertive, heroic opening of the 5th Symphony - composed to placate the disapproval of Stalin himself - but here the only assertion being presented is of ongoing tragedy. Petrenko and the orchestra convey the full, overwhelming weight of this music, a weight it feels will be impossible to lift.

This gives way to a halting lament projected with infinite shadings of timbre and dynamics by, first of all, those incredible Berlin strings, eventually joined by superlative solo and ensemble work throughout the wind and brass. This is a long movement, where lamentation and grotesquerie alternate, with massive climaxes, and Petrenko and his players hold the narrative together with an iron fist.

We then move into a pair of quintessential Shostakovich fast movements. The first morphs into almost a parody of a military march - “the intoxication of a self-satisfied band of soldiers” (a quote from musicologist Marina Sabinina cited in the set’s essays) that eventually falls apart.

The third movement proceeds over a relentless quarter-note figure that starts in the strings, eventually moving through every section of the orchestra. A relentless juggernaut of a machine that is overlaid with a recurring wailing and stabbing figure which could be the screams of someone being tortured, or maybe the unheard yells of soldiers crushed by advancing tanks. Take your pick. Eventually it dissolves into the lamentation of the Largo - a wasteland of destroyed humanity, slowly crawling through the mud and fog of war and terror.

After all this pain and suffering, the Finale begins in an almost offhand manner, insouciant bassoon and flute solos jocular and fluttering. But the shades lengthen, and the menace slowly returns, building into a massive grinding climax (a Shostakovich specialty). Thereafter, in the ashes, the survivors dance in a muted Breughelesque carnival of convulsions, with the solo violin leading the way. It’s like a distorted play on Stravinsky’s Soldier’s Tale. No one does this kind of music better than Shostakovich. The symphony doesn’t so much end as slowly peter out, all resistance gone. Nihilism incarnate.

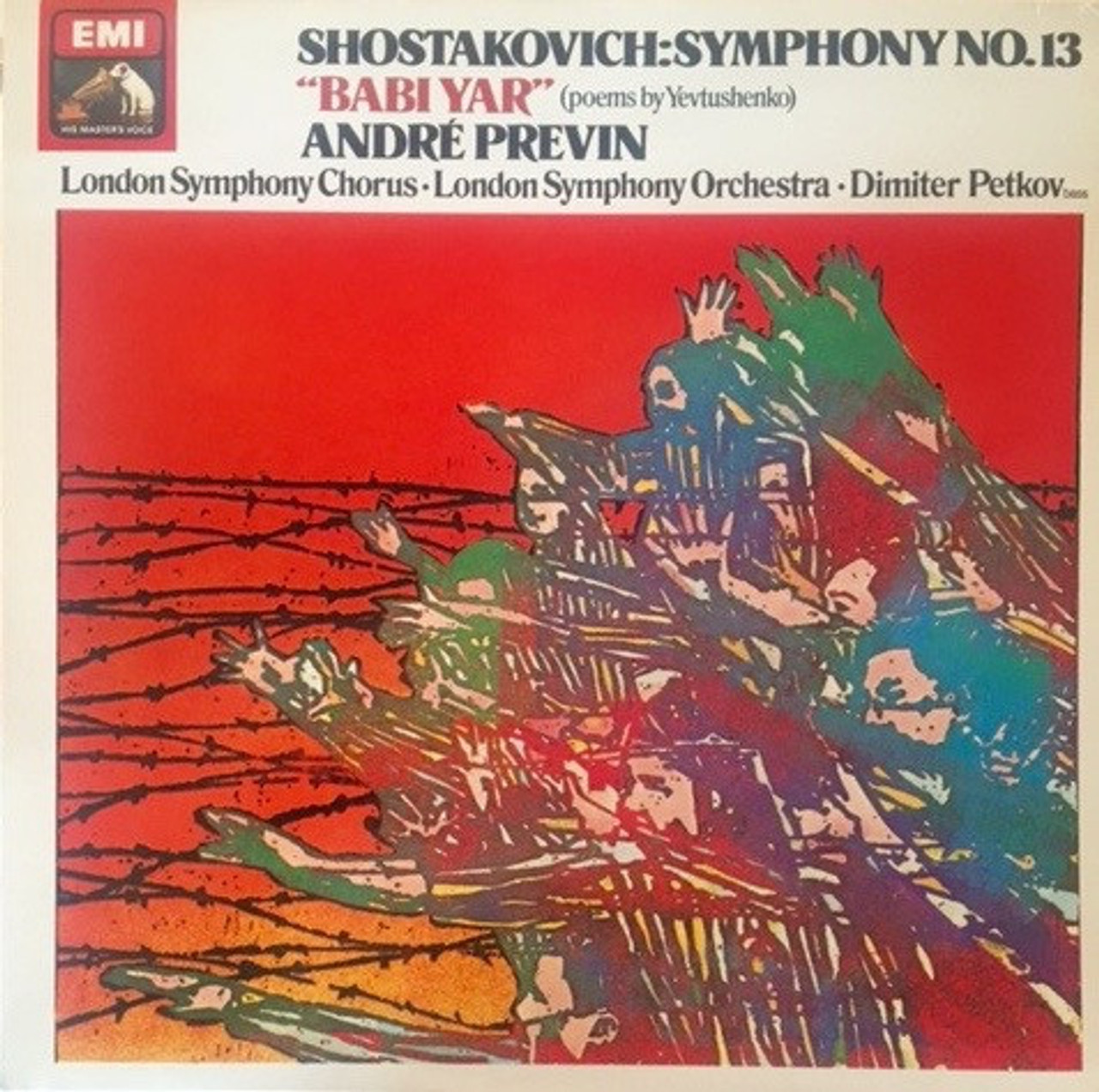

My vinyl go-to for this work has long been André Previn’s classic account with the London Symphony Orchestra on EMI, one of the finest of his essential Shostakovich recordings from the 1970s, and long considered a benchmark. It boasts excellent sonics, though suffers from long sides. (Hardcore collectors should also seek out the audiophile classic 13th Symphony, best experienced on the three-sided Alto reissue).

But this new version shoots to the top of my list. Yes it lacks the snarling abrasiveness of Soviet-era accounts, and yes, you are very definitely aware that you are listening to the plushness of the BPO, but the players really lay into this thing, no holds barred, and it is riveting.

Symphony No. 9 in E-flat major, Op. 70

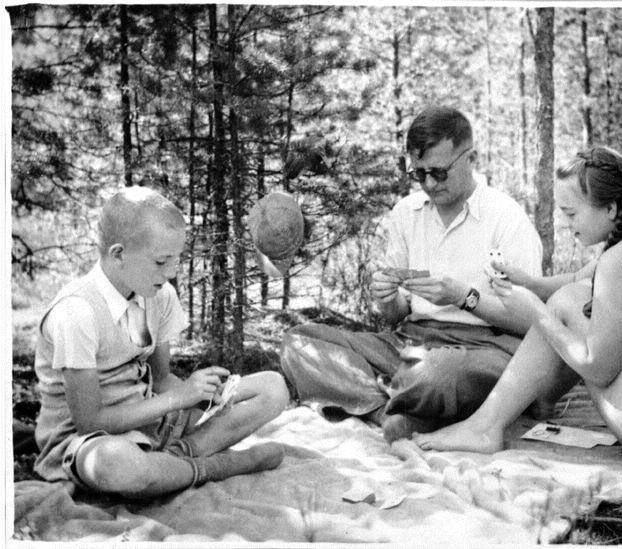

The composer playing cards with his children in the 1940s. Son Maxim, future conductor, is on the left.

The composer playing cards with his children in the 1940s. Son Maxim, future conductor, is on the left.

The 9th Symphony, premiered by the fabled partnership of Yevgeny Mravinsky and the Leningrad Philharmonic in November 1945, was supposed to be a throwback to Beethoven’s utopian vision expressed in his own Ninth - an “Ode to Joy” for the newly liberated Soviet State. The composer himself initially suggested it was going to be such a work, but then took a very different tack. The final work may be rooted in the classical form of Haydn, imbued with much of that composer’s wit, but this is a wit emerging from the years of terror and death camps, struggle and war. It is a masterpiece of misdirection. Not surprisingly it was met by criticism for its failure to “reflect the true spirit of the people of the Soviet Union”, and by 1948 had been banned. Mravinksy never conducted the work again.

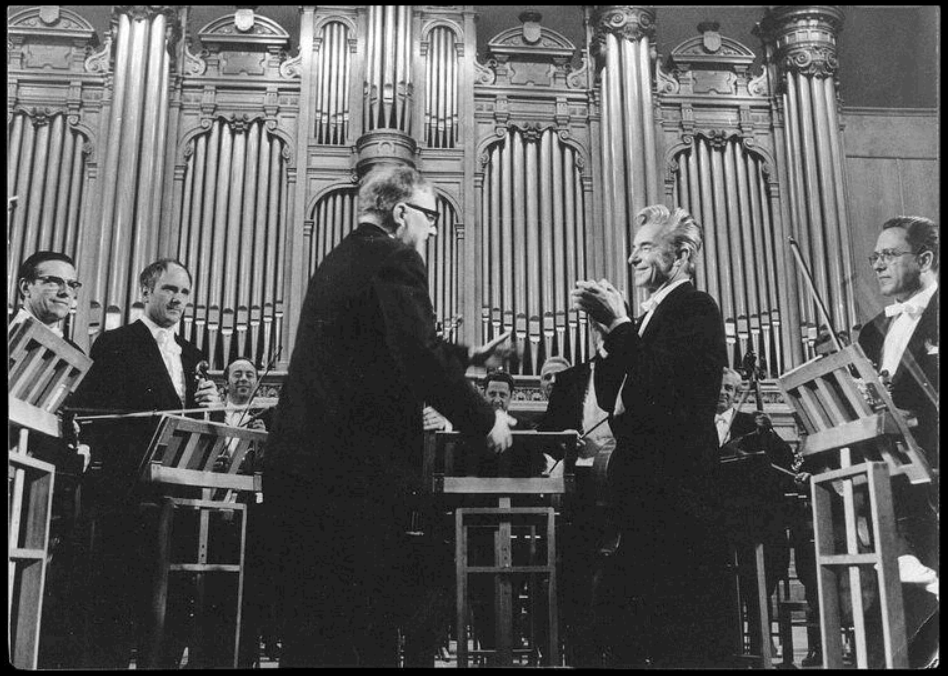

Conductor Yevgeny Mravinsky with Shostakovich

Conductor Yevgeny Mravinsky with Shostakovich

If you go straight into the 9th Symphony from the 8th you might be forgiven for thinking you have wandered into another universe, the contrast is so great. This is all Haydn-esque whimsy and jocularity, albeit filtered through a thoroughly 20th century idiom. I defy you not to thrill at the execution here, with the Berliners reveling in their virtuosity (and the virtuosity of the composer’s writing). The second movement Moderato is more whimsical still, with exquisite solo work from the Berlin wind players, which continues in the Presto, a helter-skelter roller-coaster which eventually falls apart into a dark lament.

Cue the desolate Largo. Imposing brass chords suggest a victorious army (or State) presiding over a wasteland of broken ruins. There’s nothing left to preside over. The solo bassoon calls out in the darkness, sounding like a battlefield survivor searching for his fallen comrades - or a family lamenting the loss of a loved one to Stalin’s pre-War terror, or a Syrian today entering Assad’s hellish prisons. The return of those imposing brass chords offers no solace. The State has spoken.

But now, for the final Allegretto, that same bassoon transforms into a jocular herald of another playful, classically-infused movement. I keep hearing echoes of Prokofiev’s skittish fast movements throughout this work. But, this being Shostakovich, the dark shadows return, as does a distorted March and another helter-skelter dash towards the end.

Can you imagine what the Soviet authorities thought when they walked into the concert hall, expecting to hear a heroic paean to Soviet victory, and instead they heard what could almost pass as musical mockery.

The condemnation was swift and inexorable, and the composer took the hint. No more public symphonies were produced until after Stalin’s death nearly a decade later.

Stalin (l.) with Andrei Zhdanov, architect of much of Shostakovich's misery via his authorship of the Soviet Union's post-War cultural policy

Stalin (l.) with Andrei Zhdanov, architect of much of Shostakovich's misery via his authorship of the Soviet Union's post-War cultural policy

This 9th comes at you like an express train off the tracks, darting back and forth, defying physics, but always assured of its course and purpose. It is a remarkable work that I am liking more and more as the years go by. Yes, there are other fine performances of this out there, but this Petrenko/BPO account sets a new benchmark. The orchestra is having the time of its life.

Symphony No. 10 in E minor, Op. 93

Shostakovich in the 1950s

Shostakovich in the 1950s

After the official debacle of the 9th (culminating in the work’s banning by the authorities), not surprisingly Shostakovich took a break from the composition of public works like symphonies until 1953. Stalin - the composer’s eternal bogeyman, always poised to pounce and drag him off to the Gulag - had died in March of that year. Sketches for the symphony actually date back as far as 1946. The final work, premiered again by Mravinsky and the Leningrad Philharmonic in December 1953, is generally considered the composer’s finest.

The score pits the composer’s autobiographical musical motif D-S-C-H against a range of musical incident, encompassing both his love for a student (Elmira Nazirova), and the imposing, terrible Stalin himself (supposedly portrayed in the frenetic, biting Allegro second movement, though whether this should be taken as a literal portrait of the dictator is still much discussed in musicological circles). Throughout this symphony the more extreme tendencies of Shostakovich’s style are contained and held in perfect balance within a characteristically assured formal structure. The result is a work which seems to span a lifetime, encompassing the many strands of the composer’s life - it contains multitudes. Yet it never leans too far in one direction or another. The danger is that performances can fail to capture all those facets, and not “take off” in the way that the more overtly extrovert works like the 5th (or 7th) can do.

After the extremes of the 8th and 9th, the 10th Symphony may seem like a bit of an anti-climax, but let it settle in, and its dark mysteries will enfold you. We have entered a more personal realm here. While the psychological trauma of the 8th is in your face, the interior dramas of the 10th are more veiled, revealing themselves only over repeated listenings. Built in large part from that musical motto of the composer’s own name - D-S-C-H - the symphony is almost a “coming to terms” with the Stalinist era. The first movement is a world unto itself, a portrait (maybe) of the composer confronting the vast edifice of the Stalinist State as it attempts to crush resistance - and his individuality. It’s a statement of Tragedy, of the individual attempting to survive an overwhelming weight, an unavoidable Fate, bearing down on him, and the ending - with two piccolos winding plaintively and endlessly over sustained string chords - is one of the most beautiful and shattering passages Shostakovich ever wrote.

The second movement, a startlingly fierce Allegro, was described in the controversial Testimony, purported to be the composer’s own words, as a portrait of Stalin himself. It is a slashing, relentless portrait of a remorseless dictator, propelled by his own unopposed acts to ever more giddying heights of violent oppression. This performance is fine as far as it goes, but it lacks the last ounce of shock and awe.

As he does so often, the composer follows intensity and darkness with ostensible lightness. The Allegretto opens with a lilting Ländler-like theme, which is swept aside by a more peasant-like dance. These alternating themes dominate the movement and the D-S-C-H theme is everywhere.

The final movement opens with a series of recitative-like wind solos, recounting the story so far, as it were. As the movement finally launches into another helter-skelter dash, which feels like it might want to become a celebration, there is a sense of the shadow of Stalin trying to reassert itself. But the D-S-C-H motif is ascendant, blasted out by the brass over the frenetic recall of the second movement “Stalin” Allegro figurations. At the very end, the composer’s musical leitmotif is hammered out by the timpani.

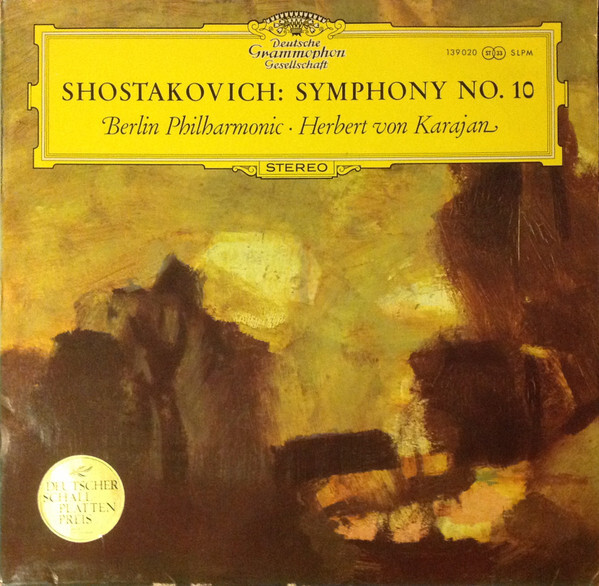

I love this work above all the other symphonies, but while there are many fine recordings, there are very few exceptional ones. If this rendition by Petrenko and the Berliners lacks the last ounce of magic that I find in, say, Karajan’s classic 1967 recording for DG with the Berlin Philharmonic (and, to a lesser degree, his 80s digital remake), it is in good company - as in, nearly every other recording of the 10th. Along with Ancerl’s white-hot mono from 1956 with the Czech Philharmonic, also on DG, Karajan is in a class of his own. (Karajan obsessives must seek out his live version in Russia from 1969 in pretty horrible sound but who cares, at which the composer was present).

The composer with Herbert von Karajan in the Moscow Conservatory's Bolshoi Hall, 1969

The composer with Herbert von Karajan in the Moscow Conservatory's Bolshoi Hall, 1969

That 1967 Karajan is best experienced either on a “large tulips” early pressing or the assured Speaker’s Corner reissue.

In conclusion…

Why is this Petrenko set so special?

First of all, these performances took place early in Kirill Petrenko’s tenure as the Berlin Phil’s new Chief Conductor (he assumed the position at the start of the ill-fated 2019-20 Season). He had already guest conducted with the orchestra extensively, and it’s those recordings that form the basis for the larger Kirill Petrenko/BPO box I will be reviewing shortly.

It was clear from the start that something special was going on between orchestra and conductor. (The Tchaikovsky 6th, recorded and released in 2017, made that old warhorse sound newly minted - in a nuclear furnace!). Not to cast shade on the Simon Rattle years, which had yielded incredible results (huge expansion of repertoire and outreach, the establishment of the orchestra’s own in-house label and streaming platform) but also highly variable performances and recordings, there was a new energy in this conductor/orchestra partnership. (And let me just state here that I while I find Rattle’s recordings frequently overpraised and underwhelming in equal measure, I did hear him conduct the BPO at the BBC Proms in the most thrilling and profound Beethoven 9th I ever expect to hear in my lifetime).

Kirill Petrenko

Kirill Petrenko

Kirill Petrenko (no relation to Vasily) was more or less an unknown amongst the classical fraternity until the BPO appointment. But to judge from his recordings with the orchestra and the handful of concerts I’ve watched on the Digital Concert Hall, he represents a bit of a throwback to previous BPO Principal Conductors like Karajan and Claudio Abbado. His very Karajan-like emphasis on sonority (he considers the strings the bedrock of the orchestral palette) is allied with an iron-like grip on the score's inner rhythm, and an associated ability to accelerate and de-accelerate without sacrificing the overall line. His extensive background in opera - like Abbado and Karajan the tradition of the Kapellmeister - has given him the ability to shape musical phrases as if they are being sung, with attendant malleability. After growing up and studying within the old-school rigors of the Russian musical educational system, Petrenko's move to Austria with his parents when he was 28 allowed him to study and expand his musical personality within a completely different tradition. How unsurprising that he should have studied conducting with Uroš Lajovic, a pupil of Hans Swarowsky, Abbado's teacher. I'd also argue that in Petrenko's conducting personality you will find a dash of the Rumanian iconoclast Sergiu Celibidache (who filled in at the helm of the BPO between Furtwängler and Karajan), at his most mischievous and rhythmically alert. (Anyone familiar only with Celi’s ponderous Bruckner is missing half of the “Celi” picture).

It’s really fun to actually watch Petrenko lead the orchestra (which you can do on this set’s blu-rays). There is intensity, yes, but also a tremendous sense of joy and simple enjoyment at hearing his incredible players do their thing. He frequently grins like the happiest little imp you’ve ever seen. There is a Toscanini-like precision of ensemble which seems new (not that the Berliners were ever imprecise) - or at least, reinvigorated.

And when the orchestra really gets into it, really gets let off the leash, there is that one-of-a-kind thrill of hearing a Rolls-Royce race around the track like it was a Ferrari. Nothing like it.

Kirill Petrenko with the BPO

Kirill Petrenko with the BPO

There’s something else at play here. Petrenko really “gets” this music. Not all conductors do. Plenty perform it, and perform it well, but Petrenko seriously “gets” it. He’s alert to the pain, the anguish, the sardonic wit, the biting bitterness, the yearning that chills, the heat that cools. He gets the paradoxical heart beating in these symphonies. He dives into the raging waters even as he can also ascend to the heights and look down on the madness with perspective. He has the full measure of not just the music itself, but of the life lived in the music. He always makes the purely musical argument clear, while also communicating the extra-musical one.

Most conductors tilt more to one side of the composer’s personality than to the other. Petrenko presents the man and music complete, unified - or at least as complete and unified as this multi-faceted, multi-dimensional music will allow. There remains, as always with Shostakovich, the glimpse of another yet-to-be-revealed truth lurking in the corner of one’s eye, always out of reach. The enigma of this great Russian composer abides.

In sum, I can think of no better clutch of orchestral works to capture the essence of what Shostakovich is all about (for his more interior realm you will have to dive into the equally extraordinary chamber music).

EXPLORING OTHER SHOSTAKOVICH SYMPHONY RECORDINGS

There are many, many recordings of this repertoire out there, from Soviet, post-Soviet, European and American conductors and orchestras of the finest calibre. As our world shifts into ever more fraught and dangerous waters, Shostakovich’s struggles with his external and internal demons, expressed in music that never fails to communicate like it is hardwired into our veins, feels more and more relevant to our current fractured state. So no surprise that the marketplace continues to supply our Shostakovich fix with individual recordings and complete cycles.

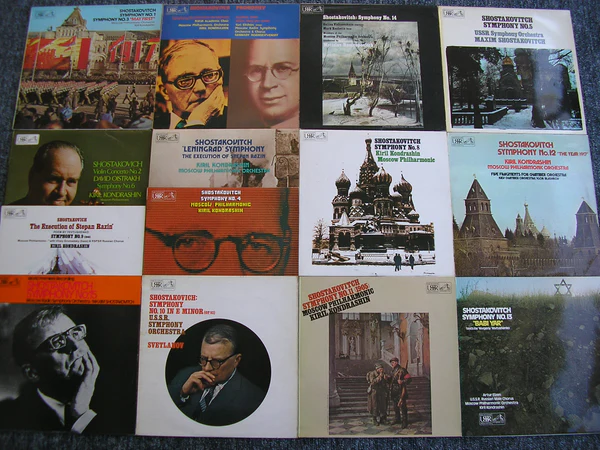

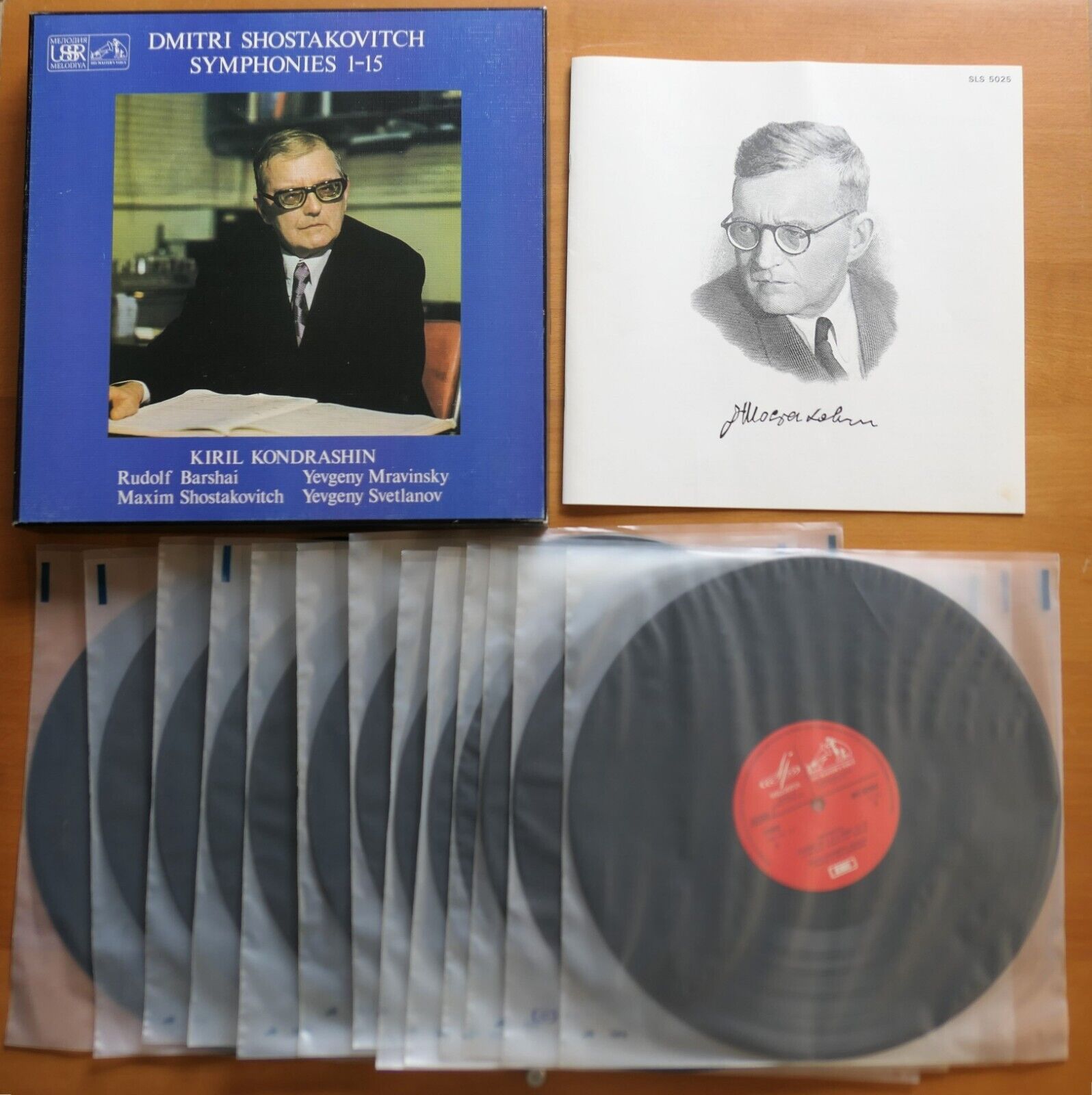

But new recordings have to be very special indeed to dispel the long shadows of previous benchmarks. For a start, no-one remotely interested in this repertoire should fail to explore the numerous Soviet era outings from Mravinsky, Svetlanov, Kondrashin, Rozhdestvensky et al on Melodiya (EMI UK), let alone the composer’s own son Maxim, whose account of the 15th Symphony for Melodiya remains definitive to this day (and superb sonically).

Assorted Soviet era recordings of Shostakovich symphonies released on EMI/Melodiya in the 1960s/70s

Assorted Soviet era recordings of Shostakovich symphonies released on EMI/Melodiya in the 1960s/70s

If you can find a copy (and it will be pricey), this EMI collection of Melodiya recordings is an essential compendium of the best of the Soviet era on vinyl (and it contains that 15th I just mentioned). It's one of my most prized vinyl sets - I bought it when it came out in 1975.

Post-Soviet cycles by Rudolf Barshai, Kurt Sanderling, Vasily Petrenko (in Liverpool of all places) and Mariss Jansons are likewise essential; Rostropovich’s cycle, alas, is more variable.

I highly recommend this set. Barshai had a long connection with the composer's music, as a violinist, arranger and conductor. He conducted the premiere recording of the 14th Symphony.

I highly recommend this set. Barshai had a long connection with the composer's music, as a violinist, arranger and conductor. He conducted the premiere recording of the 14th Symphony.

Of the Europeans, Bernard Haitink is always a reliable centrist recommendation, not as intense or extreme as some would like (but that is Haitink’s way), but no shrinking violet either, and always in excellent Decca sound (mostly digital). As I’ve already mentioned, Previn’s LSO/EMI records will satisfy both musically and sonically.

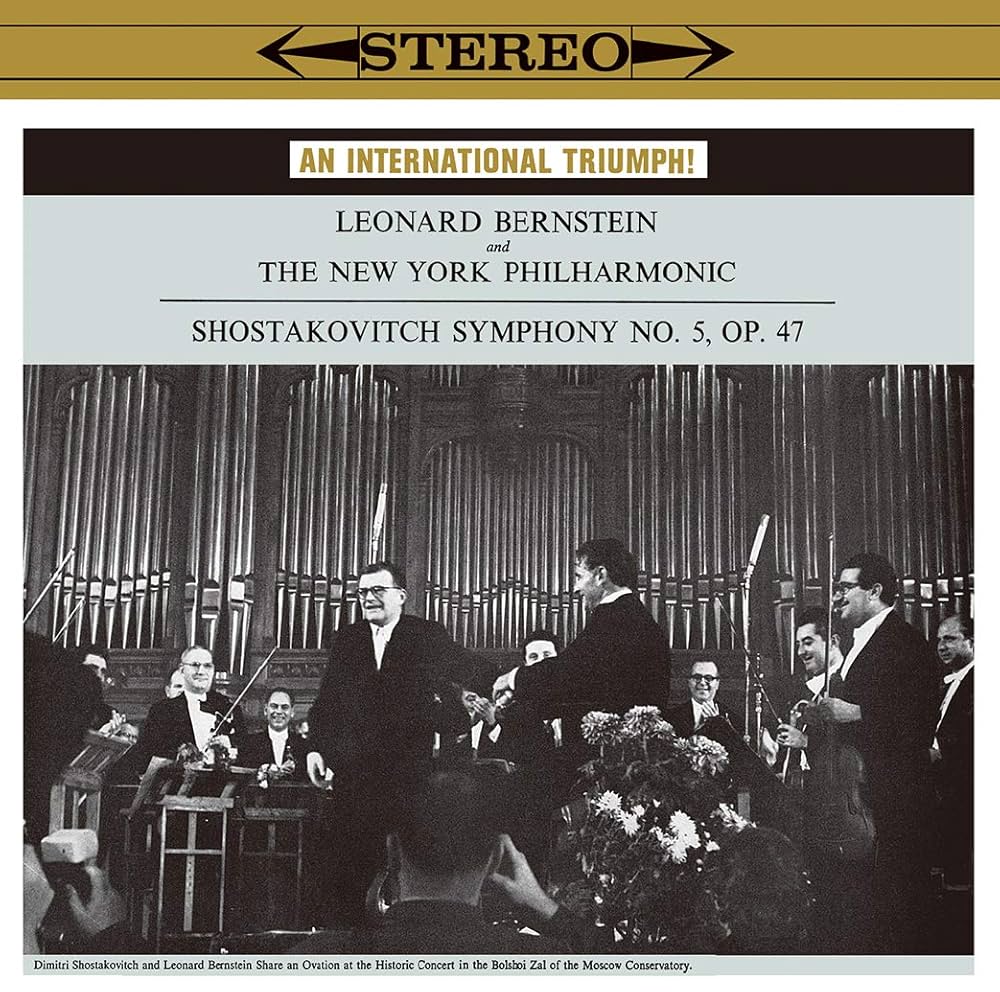

Leonard Bernstein’s few recordings channel his Mahler gene to similarly gripping effect - his 1959 5th on CBS/Columbia (especially in its its vinyl audiophile reissue) remains the one essential version of that work that every Shostakovich fan should own.

His DG “Leningrad” with the Chicago Symphony on excoriating form is also essential, as is his pairing of the 6th and 9th with the Vienna Philharmonic for the same label.

However, this box from the BPO and Petrenko gives us three of the very best recent Shostakovich recordings I have heard, in stunningly vivid sound (and yes, these are “just” CDs - you need make no allowances). This is about as good as CD sound gets.

As with all CD/Blu-ray versions of these BPO releases, the discs come in a deluxe, elongated box, featuring special artwork and photography to create an overall “conceptual” design in keeping with the music contained within. In this case a contrast is being drawn between the anonymous, totalitarian image of a bank of lockers on the cover with flower photography scattered throughout the booklet: read into it what you will.

Some will be irritated by this - I think it works. As always, insightful essays and notes provide an illuminating addendum. The blu-rays feature the concerts themselves, filmed unobtrusively and sensitively, and extended interviews with Petrenko. I am not a big watcher of concert videos, but these are thoroughly engaging, and offer another dimension to the performances. If you get the set, you will definitely augment your experience by watching them. The visual reminders of the pandemic (social distancing, masks, empty seats) are suitably sobering, and reinforce the music’s undercurrents in quite an unsettling manner.

This is music of such urgency and relevance, it demands to be heard - especially at this moment. As conductor Kirill Petrenko puts it in his introduction to this set:

“Everything to which Shostakovich gave such graphically explicit expression, and which we believed was surmounted, we ourselves are shockingly experiencing today. Especially at a time like this, his music provides confidence and strength to believe in the ideals of freedom and democracy. Shostakovich is a model who gives us courage.”

FURTHER READING:

Just published is what promises to be a fascinating study of Shostakovich's 5th Symphony, the work he composed as "an artist's reply to just criticism" in the wake of Stalin's disapproval of the opera Lady Macbeth of Msensk. One of the authors, Marina Frolova-Walker, is a foremost scholar of Russian music, and a regular contributor to BBC Radio 3's Record Review.

This tells the extraordinary (and harrowing) tale of the Siege of Leningrad and the composition of Shostakovich's mighty symphony, and how it related to the Stalin terror of the pre-War years. The score had to be smuggled out of the city, taken across occupied Europe, and thence to the US where it was premiered by Toscanini on the radio. This was an early mission of the American OSS, (Office of Strategic Services), later the CIA.

Available only at the Berlin Philharmonic website

.png)