The Strauss Sound Reborn - The Waltz King Lives!

Decca’s Pure Analogue Series kicks off by reverse engineering the label’s first commercially released digital extravaganza from 1979, giving it new life via an all-analogue cut from a newly unearthed analogue master. Who would ever have thunk it?!

THE ROAD TO DECCA PURE ANALOGUE

For both novice and seasoned classical collectors, the Decca label has long held a special allure and magic, akin to Mercury Living Presence and RCA Living Stereo in the USA, and Columbia EMI/HMV in England. This is because the label has always entertained a reputation for superb, audiophile sound, combined with a catalogue of performers and performances fully the equal of any other classical label, fully deserving the appellation of “legendary”.

Generations of seasoned collectors (myself included) have hunted down original and later pressings of Decca titles (and in the US sought out “Made in UK” pressings on the London label, the name under which Decca distributed its catalogue in the States). For those balking at the high cost of early “wide-band” pressings, seeking out later “narrow-band” pressings, even those pressed in Holland as became the custom in the later 1970s and 80s, was a perfectly viable alternative if you simply had to have the record at a reasonable price. And of course, the label itself would also reissue many of its recordings over the years, often using the same metal parts as were used for the earliest pressings; hence the possibility of finding almost facsimile versions of financially inaccessible titles on the Ace of Diamonds, Eclipse, and World of the Great Classics imprints. Serious collectors will still debate the relative sonic merits of “wide-band” vs. “narrow-band” pressings, the difference being the former were mastered with tubes in the mastering chain, but often with inferior quality vinyl and pressing technology. (I welcome your comments - I think…)

Then, in the last few decades, those who were willing to forgo the cachet of owning an original pressing began to be able to buy modern vinyl reissues mastered and pressed all-analogue either directly from the master tapes, or from one-to-one tape copies of same, on specialty reissue labels like Mobile Fidelity, Speaker’s Corner, Analogue Productions, Alto, ORG, etc. Often these reissues matched as closely to originals as to make it hard to tell the difference, and always came with the advantage of much quieter 180-gram vinyl, and immaculate sleeves (even if they glossed over some of the details of the originals, like foldover construction).

However this remained very much a niche market within the already niche audiophile vinyl market, even though other classical labels like Columbia US, Deutsche Grammophon, EMI, Mercury and RCA began to see certain titles given exemplary AAA reissues by the reissue labels mentioned above, joined by Classic Records, Clearaudio, Analogphonic, Testament, HiQ etc.

As the vinyl Renaissance really took off in the last decade, it remained an open question as to whether any of the parent classical labels would take the plunge themselves into the all-analogue vinyl reissue game.

Some years ago Speaker’s Corner began to get out of the classical vinyl market, letting most if not all of its records go out-of-print - which seemed very strange just as everyone else seemed to be getting into the business of AAA vinyl reissues.

Meanwhile, the classical labels themselves started jumping on the vinyl gravy train by reissuing older classic titles, but - alas - always from digital files, and often with shoddy craftsmanship. This was absolutely not what any of the collectors really wanted, so those releases often just sat in the bins for months.

Then, three years ago, something happened which changed the whole landscape. Deutsche Grammophon, not hitherto identified as an audiophile label by collectors (beyond early tube-mastered “large tulip” pressings), began its Original Source AAA vinyl reissue series, under the watchful eye of Johannes Gleim (head of DG’s Historic Catalogue) and via the brilliant, innovative engineering skills of Rainer Maillard at Emil Berliner Studios, partnering with a brilliant young disc cutter named Sidney C. Meyer, who had recently spent time honing her skills in the company of the great mastering engineer Kevin Gray.

Rainer Maillard and Sidney C. Meyer creating vinyl magic in Emil Berliner Studios

Rainer Maillard and Sidney C. Meyer creating vinyl magic in Emil Berliner Studios

What was even more surprising was that the Original Source Series focused not on the older catalogue from the 1950s and 1960s, but on the 1970s catalogue, its least favoured era by classical vinyl collectors. Why? Because, as it turned out, what was on the actual multitrack master tapes was a little different from what we’d heard on the original records and then CDs. Many of these recordings had been made to 4 and 8-track masters with two channels of dedicated room ambience, captured by two mics planted in the depths of whatever hall was being recorded in. Recordings had been made like this with the notion of the label entering the Quadraphonic market - something which never happened. But those master tapes, fully edited, had just been sitting in the archive, waiting to be plucked forth. (Some tapes were given a hi-def release on SACD - a taster for the treasure lurking in those cavernous vaults).

At Emil Berliner Studios, Maillard (who had begun his career as an engineer at DG in the all-digital age, but had long championed vinyl, especially in his remarkable Direct-to-Disc releases for the Berlin Philharmonic) built a dedicated mixing and mastering chain that enabled him and Meyer to cut directly from the 4 and 8-track master tapes, something which had never been done before by anyone. All regular stereo records back in the day were cut from 2-track mix downs. This had also included the few modern AAA reissues. Indeed, as we learned for the first time with the advent of the Original Source Series, DG had further sonically compromised its initial vinyl releases in the 1970s by deliberately rolling back dynamics and frequency response, in order to head off any potential problems or inconsistencies arising from variations in pressing quality at its various international pressing plants.

For the Original Source reissues, Maillard and Meyer also developed proprietary technology and techniques in collaboration with Optimal to enable more dynamic cuts - and dynamic indeed they are!

The results were nothing short of revelatory, rewriting the sonic history of the label, and sufficiently successful in terms of sales to mean that the series continues ever onwards.

This success also provided a model for another classical label with deep vaults to jump into the fray - which turned about to be DG’s label mate at Universal Music Group, Decca.

Which is so interesting, given the fact that Decca already has a stellar reputation amongst audiophiles. Beyond simply making older titles more easily available, was there really that much to be gained sonically by embarking on an extensive AAA reissue campaign? Decca would be emulating DG by using the skills of Maillard and Meyer, but unlike DG would not be mastering from a source that included surround sound channels, because Decca had never embraced that technology?

Well, as it turned out, there may be quite a lot of added sonic excellence to be extracted from those already excellent old master tapes, for a number of reasons.

In addition, as Decca began digging through its vaults to hunt down suitable titles for the Decca Pure Analogue series, it discovered that in fact some quadraphonic sessions were indeed committed to tape, both in-house and at Philips, whose catalogue is now part of Decca.

For a refresher on the advent of the Decca Pure Analogue reissue series, I refer you to my earlier article. But by way of a quick recap, for now the Decca Pure Analogue series is focusing on three areas:

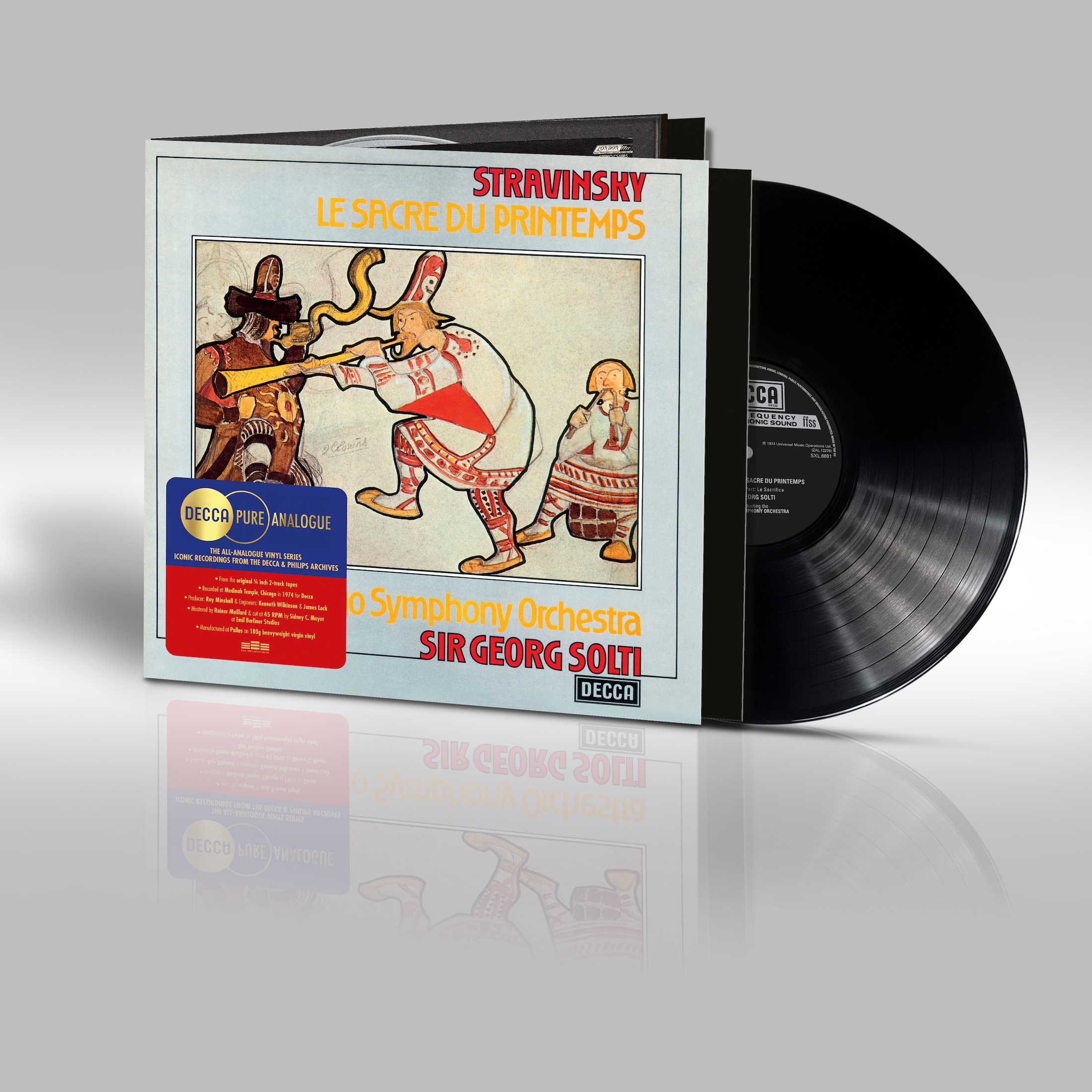

1/ New cuts of Decca titles (eg. the Solti/Rite of Spring being released in this first batch, cut for the first time at 45rpm);

2/ New cuts of Philips titles, since Philips is now part of Decca AND, as it turns out, did in fact make some recordings with surround sound (represented in this first batch by the Colin Davis/Sibelius symphonies release);

3/ New cuts of Decca’s early digital releases, now mastered from back-up analogue master tapes which have been sitting in the vault unplayed for over forty years.

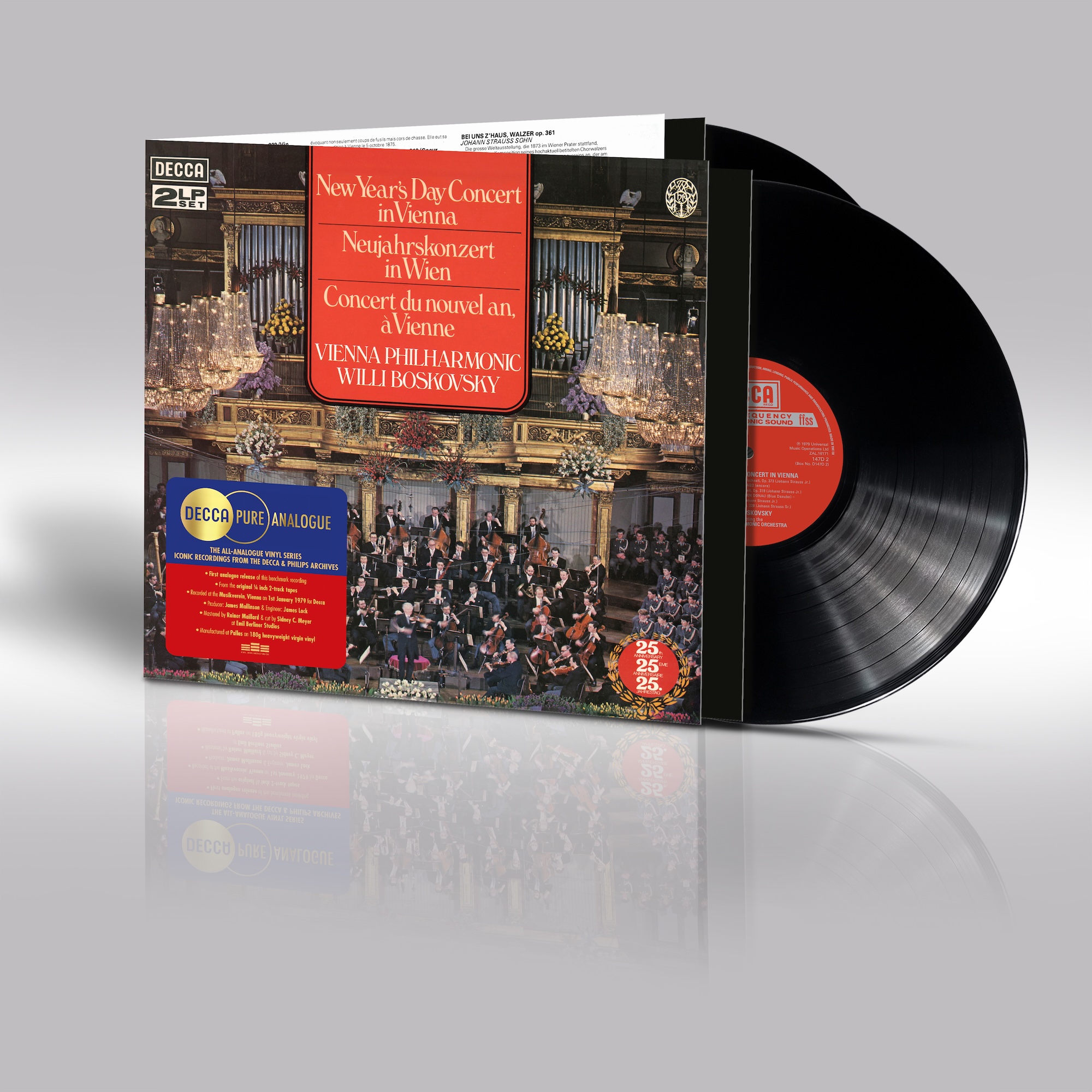

It is with the release of a title from this third category that I am concerning myself here - the 1979 New Year’s Day Concert from Vienna.

My colleagues Michael Johnson and Paul Seydor will be reviewing the other two releases in the days ahead (MJ reviewing the Solti; PS reviewing the Sibelius).

It’s all hands on the Tracking Angle deck for this important moment in the history of classical audiophile vinyl reissues!

There is also going to be a substantial video conversation with all the interested parties at Decca, DG, and Emil Berliner Studios released in the next few days which will give you even more information and details to chew on. Watch out for that!

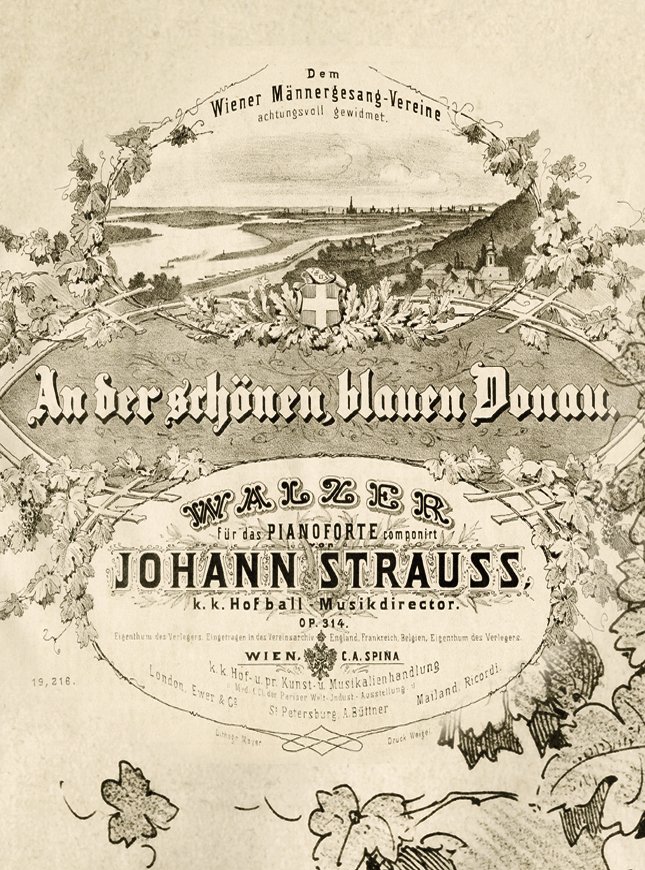

So now let’s turn to the music of Johann Strauss & co, as captured by the Decca engineers live in the Musikverein on January 1st, 1979 - and released later that year as Decca’s first all-digital recording.

VIENNA AND THE WALTZ

“My beloved city Vienna, in whose soil is rooted my whole strength, in whose air floated the melodies my heart drank in, and my hand wrote down.” —Johann Strauss II

Is there any city in the world that can claim as close an identification with a specific musical form as Vienna can with the waltz?

At the time of the ascendancy of the Strauss family in the mid-19th century, Vienna had long been considered the musical capital of the world. The city dominated European culture, owing in part to its key geographical position, connecting the west to Hungary and beyond to Russia, and being the epicenter of the Habsburg dynasty and later Austrian Empire. However, in the 20th century, its key role in the rise of the Nazi Party (and attendant anti-semitism) may have reaped short term political benefits, but continues to cast a long shadow.

This was where Mozart had come to seek fame and fortune, and likewise Beethoven made it his home for most of his life. The city would continue to dominate the classical music world in the 19th and 20th centuries, with its famed Viennese Philharmonic Orchestra acting as a magnet both because of its concerts at the Musikverein Concert Hall, and its role as the “house band” at the Vienna State Opera.

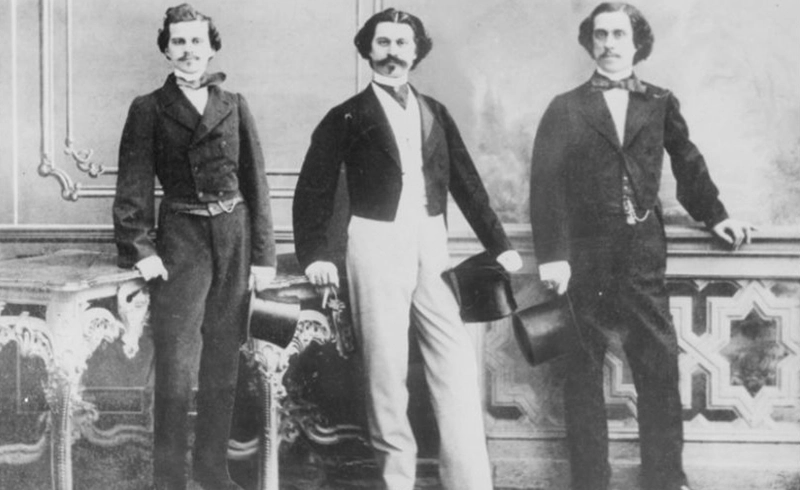

But the Strauss family, beginning with Johann Strauss I (Senior), continuing with his sons Johann Strauss II (Junior), Josef and Eduard, belonged in the world of light music. They were the ones who turned the waltz (and also other forms of popular dances like the polka) into the 19th century equivalent of a dance craze like the twist. Adventure-seeking aristocrats would slip away from home to enjoy the vicarious thrills of dancing a waltz with a closely held partner at one of their servants’ favored dance halls. Indeed the waltz gained a certain verboten allure owing to its call for close contact between dancers, and the thinly veiled sexual allure of its sinuous 3/4 time signature. The waltz itself had been around in various forms for a century or two before its breakthrough in the compositions of Strauss Senior, who also led his popular band from his violin.

Pater Strauss was none too keen for his sons to enter the lucrative family business, and Johann Junior had to take violin and music lessons on the QT, eventually setting up a rival orchestra, much to his father’s chagrin.

But with the passing of his father in 1849, Johann Jr., receiving the full support of his mother, combined the two bands, and went on to have a stellar career, becoming crowned as “The Waltz King”. While there are a number of famous compositions penned by his father, not least the Radetzky March which closes every New Year’s Day Concert, it is the music of Johann Strauss II which has come to epitomize the Viennese “light style”, exemplified by his operetta Die Fledermaus, and the Blue Danube Waltz.

.png) Johann Strauss II by Theo Zasche

Johann Strauss II by Theo Zasche

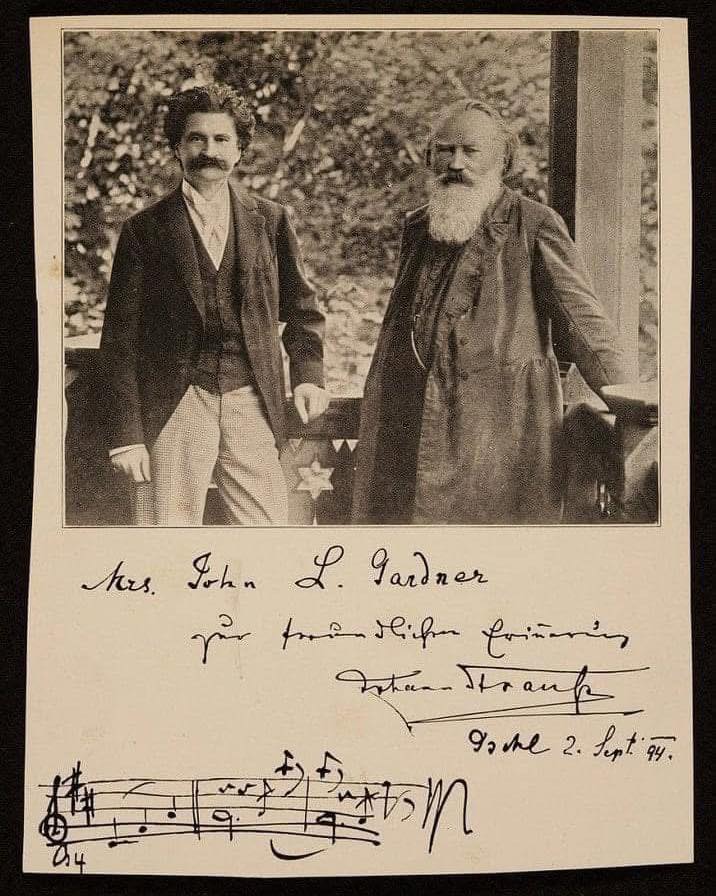

In the hands of Johann Strauss, the waltz evolves from a simple dance into a fully realized tone poem, able to occupy a concert program alongside the more “serious” music of his contemporaries. Brahms himself was a huge admirer, becoming friends with the composer. The story oft told is that asked to sign a fan belonging to Strauss’s wife, Brahms wrote a few notes of The Blue Danube, adding “Unfortunately not written by Johannes Brahms”. (This story does the rounds in several variations).

1894 photo of Johann Strauss II with Johannes Brahms, presented to US philanthropist Isabella Stewart Gardner. Signed by Strauss with Blue Danube fragment (Photo: Smithsonian)

1894 photo of Johann Strauss II with Johannes Brahms, presented to US philanthropist Isabella Stewart Gardner. Signed by Strauss with Blue Danube fragment (Photo: Smithsonian)

Beyond Strauss’s lifetime the waltz as a self-contained tone poem (as opposed to featuring in ballets and symphonies) reached its apotheosis in the hands of Maurice Ravel's La Valse (1920), which has come to be seen as a thinly veiled reference to the cataclysms of the 20th century. Originally conceived as a ballet for the influential Ballet Russes titled “Vienna”, but rejected by Diaghilev, it is more often heard in the concert hall. It prompted this observation by the English composer George Benjamin:

"Whether or not it was intended as a metaphor for the predicament of European civilization in the aftermath of the Great War, its one-movement design plots the birth, decay and destruction of a musical genre: the waltz.”

Ravel himself disagreed with that characterization, though.

Interestingly, the waltz continued to permeate popular culture through to the present day, most famously perhaps in Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey. Rejecting Alex North’s specially composed score, the director chose instead to set his technological spectacular to existing classical works, and brilliantly set the sequences of orbiting space craft to the strains of The Blue Danube, thereby imbuing the sequence with all manner of thematic resonances and sexual innuendo as alternately “male” and “female” space craft indulged in celestial flirtation and coitus.

A lesser known but no less brilliant use of the waltz in films comes in Max Ophuls’s The Earrings of Madame de… (1953), in which the growing illicit passion of the film’s two lovers is charted over an extended waltz sequence, which Ophuls captures with equally dancing and interweaving camera moves.

Ophuls was one of Stanley Kubrick’s favorite directors, and the sequence is referenced in an equivalent dance scene at the opening party of Eyes Wide Shut (1999), where a random randy Hungarian attempts to seduce Nicole Kidman. (A key music cue used in the film is that of Shostakovich’s Waltz No. 2 from his Suite for Variety Orchestra, sometimes mislabelled as Jazz Suite No. 2).

In short, the waltz as developed and brought into its maturity by Johann Strauss II has remained a musical form that not only continues to inspire composers, but also continues to resonate within the culture to the present day. Hell, it even inspired a whole album by Malcolm McLaren!

THE NEW YEAR’S DAY CONCERT - BACKGROUND and HISTORY

Willi Boskovsky and the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra, New Year's Day Concert (Photo: Decca)

Willi Boskovsky and the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra, New Year's Day Concert (Photo: Decca)

The New Year’s Day Concert in Vienna has become one of those rare global classical events that spills over into the popular culture, akin to the Last Night of the Proms and the Christmas Eve Lesson and Carols from King’s College, Cambridge. It is filmed and broadcast to a huge global audience, and these days the resulting audio CD is made available within a ridiculously short period of time (the 2026 concert is already for sale). The announcement of who is going to conduct the concert has become as highly anticipated in the classical world as have the Oscar nominations in the film world. Quite apart from the huge visibility and honor engendered by conducting the concert, it’s also a Big Paycheck, big enough that the exact amount is not disclosed.

But back in 1979 things were very different.

For over 25 years the New Year’s Concert had been led by the orchestra’s concert master, Willi Boskovsky who - like Strauss before him - would frequently pick up his violin to play along with the band.

Willi Boskovsky

Willi Boskovsky

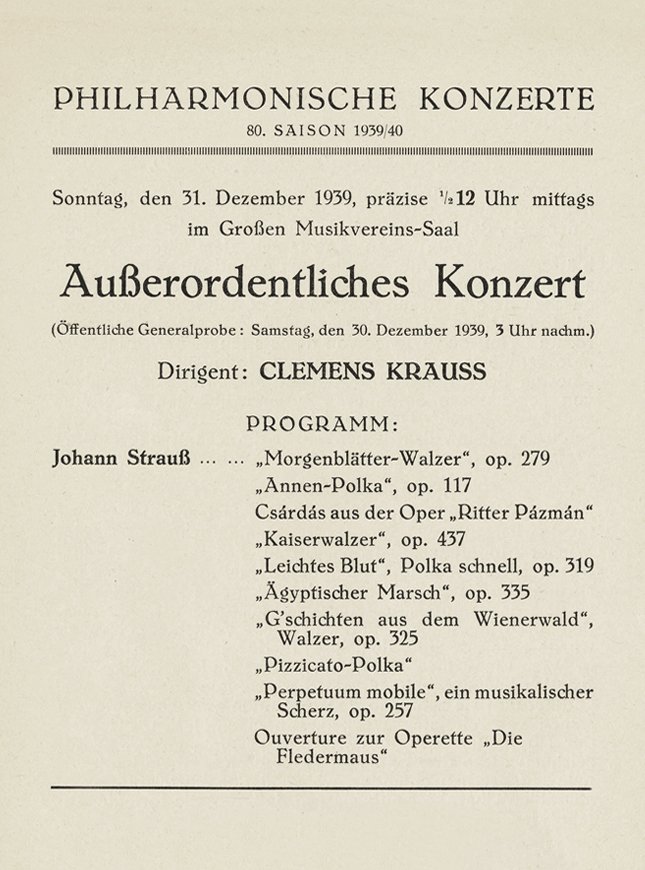

He had inherited the job from Clemens Krauss, the mighty Austrian conductor who had presided over the first New Year’s Day Concert in 1939, enacted as a fundraising event for the National Socialist Party (ie. the Nazis).

Program for the first New Year's Day Concert in Vienna in 1939

Program for the first New Year's Day Concert in Vienna in 1939

The orchestra’s relationship with Strauss’s music had been sporadic during the composer’s lifetime, since this was considered “light music”. The celebrated Arthur Nikisch programmed some key works at the unveiling of the Johann Strauss Memorial in 1921, and then finally in 1925 a whole concert was dedicated to Strauss, conducted by Felix von Weingartner.

But it was Krauss who fully established the VPO-Strauss tradition, returning to conducting the New Year’s Day concert after his denazification in 1948.

Clemens Krauss

Clemens Krauss

With Krauss’s sudden death in 1954, the orchestra considered ending the concerts as a sign of respect to the conductor, then endeavored to find a replacement, offering the job to Erich Kleiber, who declined. More votes brought them no closer to finding a replacement, then finally, with two weeks to go before the show, they turned to their concertmaster, Willi Boskovsky.

Decca Classics Label Director, Dominic Fyfe, takes up the story in his excellent essay that accompanies this Decca Pure Analogue Reissue, included on a special insert.

There is a touching photograph of Clemens Krauss shaking hands with Boskovsky at the concert on 1st January 1954, neither man knowing that from the following year - and for the next quarter century - Boskovsky would make the New Year’s Day Concert his own.

There had been some ambivalence within the orchestra about giving Boskovsky the job. John Culshaw, Decca’s producer in Vienna, takes up the story: “The orchestra hated him, but audiences the world over came to love him. He exuded the popular Viennese image. Compared with Krauss he had little conducting talent, but he had something Krauss lacked and which provided a direct connection with Johann Strauss himself - namely that he could pick up his violin when he felt like it and just play along with the orchestra.”

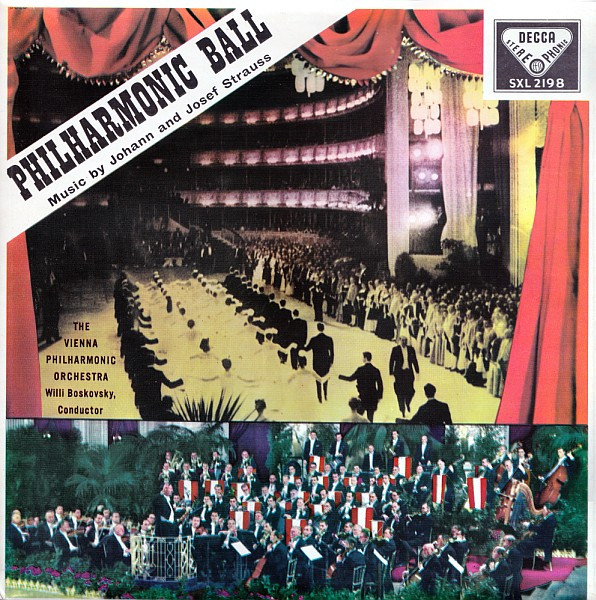

It was a winning formula. In 1959 the concert was televised for the first time and from 1966, capitalizing on a global audience, Decca once again began branding its albums of Strauss waltzes, “New Year’s Concert”.

I own nearly all those classic early Decca Boskovsky/VPO Strauss records (all recorded in the studio, ie. the Sofiensaal) in early wide-band pressings. They capture the whole echt Strauss/VPO vibe to perfection, and sound marvelous.

The Decca team was getting first rate sound in Vienna in those days.

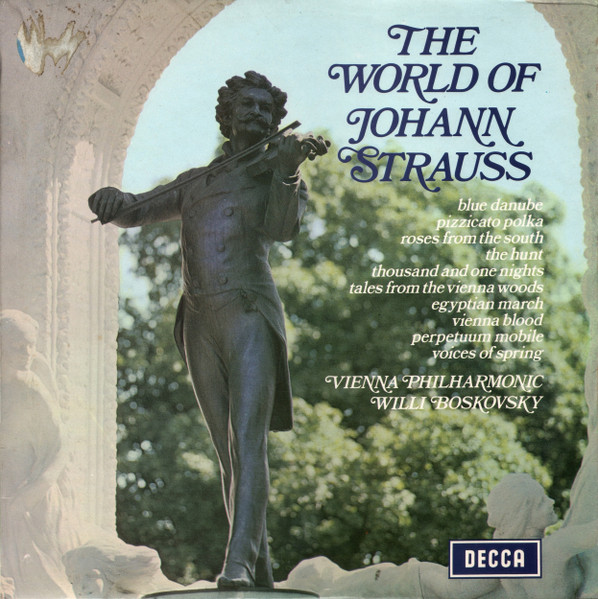

At a far earlier age, at the outset of my record collecting career, I owned the highlights of these records in two colorful entries in Decca’s World of the Great Classics series of reissues. These sound excellent too, if lacking the ultimate bloom of the tube-mastered originals. No Strauss lover should be without some sample of these classic recordings in their collection.

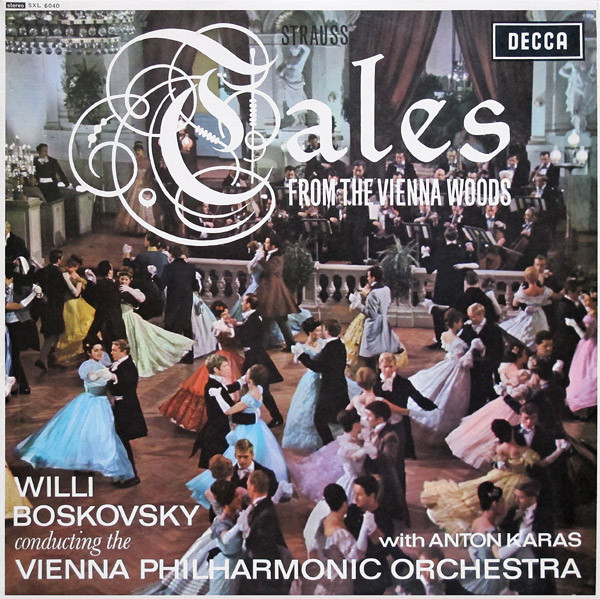

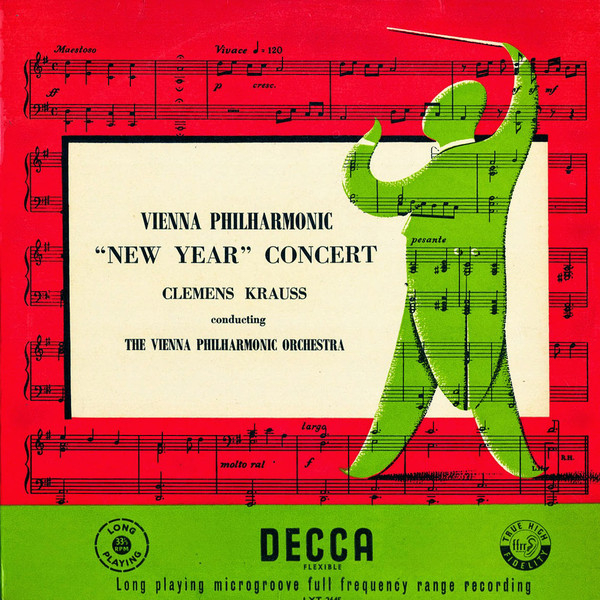

And here's one of the ravishing covers for a Clemens Krauss mono record of Strauss waltzes from 1955. Krauss's series of Strauss records really established the template for the echt-Strauss performing tradition in Vienna, and are quite marvelous in their own right.

And here's one of the ravishing covers for a Clemens Krauss mono record of Strauss waltzes from 1955. Krauss's series of Strauss records really established the template for the echt-Strauss performing tradition in Vienna, and are quite marvelous in their own right.

DECCA and the THE DAWN OF THE DIGITAL AGE

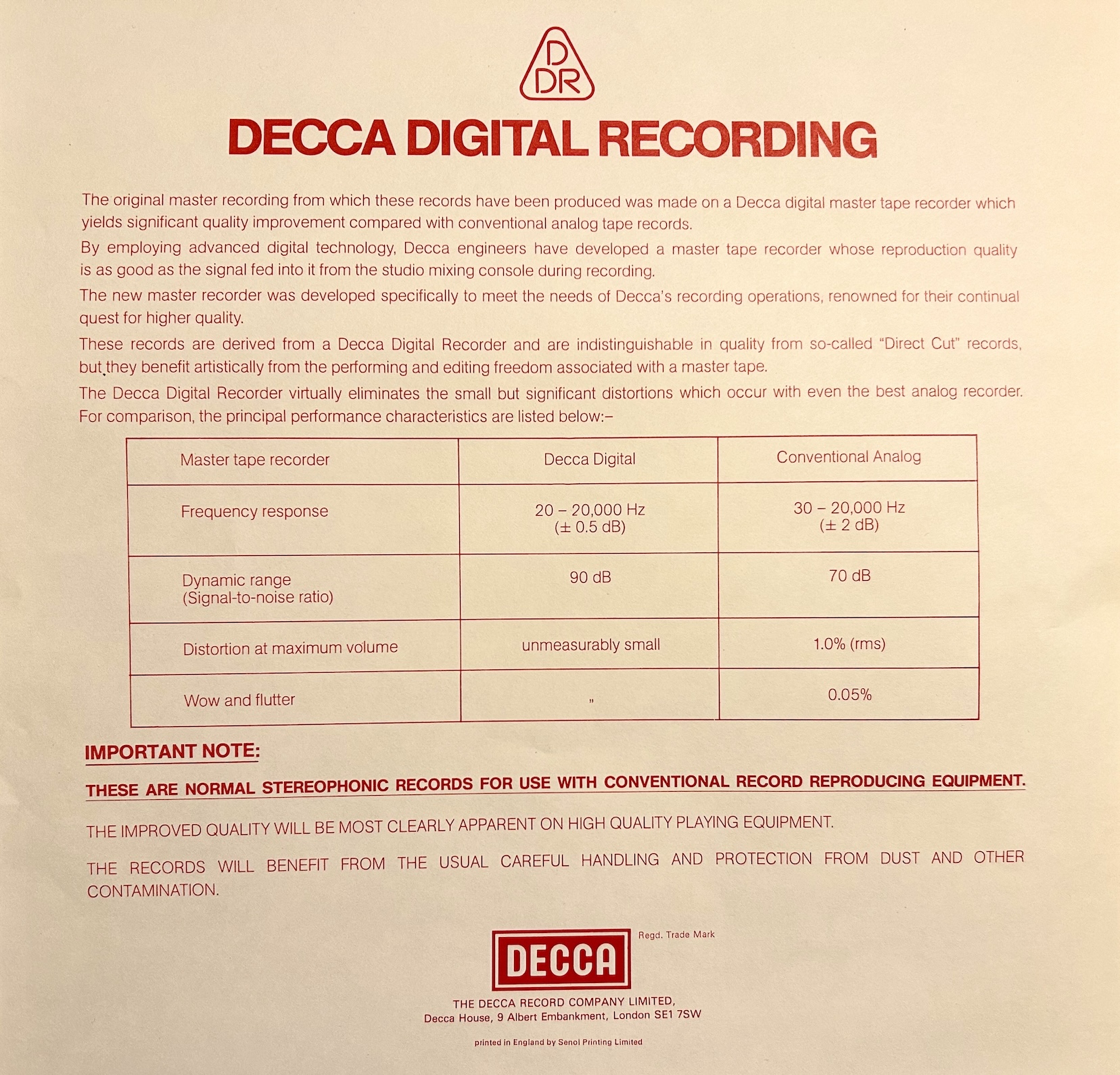

Insert included with the original vinyl release of the 1979 New Year's Day Concert in Vienna

Insert included with the original vinyl release of the 1979 New Year's Day Concert in Vienna

In his accompanying essay, Dominic Fyfe outlines the steps that led up to Decca’s full embrace of digital technology, which resulted in their first commercial digital release - of the 1979 New Year’s Day Concert. First came sessions earlier in December 1978 to record Christoph von Dohnányi conducting the VPO in Mendelssohn’s “Italian” Symphony. These used (Fyfe) - “Decca’s proprietary digital recording system with its IVC (International Video Corporation) one-inch videotape recorder, capable of encoding at 18-bit/48kHz resolution. This was already a step ahead of the prevailing Red Book standard of 16-bit/44.1kHz. At the end of the month, it was moved to the Musikverein to capture the present New Year’s Day Concert.”

Fyfe continues:

The assistant producer on those recordings, Andrew Cornall, recalls how fragile and unreliable those early digital recordings could be. The editing, he remembers, was especially laborious: “Editing took an age, even though there wasn’t that much obviously”. With huge investment at stake, it wasn’t just precautionary to run trusted analogue machines in parallel with digital, it was essential. Decca was still happily wedded to its analogue 1960s Roy Wallace-designed STORM (STEREO REMOTE MIXER) mixing desk where, quite simply, one output fed the digital system and another the analogue back-up. This dual approach was used throughout the late 1970s and into the early 1980s. Decca was not alone in this. Most famously, perhaps, the 1981 Glenn Gould Goldberg Variations were recorded by CBS both digitally and in analogue; indeed, since the 2002 “State of Wonder” reissue of Gould’s performance the analogue tapes have always been preferred.

THE MUSIC and HOW DOES IT SOUND?

Digital OG vs. Decca Pure Analogue

First things first. I dug out my original copy of the double LP set, which I bought when it was first released. I remember at the time being blown away by the immediacy of the audience, the attack of the percussion, and the incredibly lifelike gunshots that accompanied the novelty polka At the Hunt which provoke the required audience gasps.

In other words I reacted to the digital technology in the same way that millions did upon first hearing it - we absolutely loved the moments of high percussive impact, the sense of spectacle brought up close and personal into the listening room.

Some of this was down to how the concert was miked by the original balance engineer Jimmy Lock. As Fyfe notes, “he later mentioned to his Decca colleagues that he had deliberately recorded in close-up to demonstrate the transparency of the new technology”.

Side 4 of my original pressing was a regular visitor to my turntable as I moved into my 20s, since it featured a rather splendid procession of Strauss assortments, highlighting the Big Hits. After that adrenalin-pumping polka (and its required encore with attendant audience hilarity), we are treated to the effervescent Leichtes Blut (or Light of Heart) Polka, leading into the evergreen Blue Danube Waltz, and finally the Teutonic knees-up of the Radetzky March by Strauss Senior. During this it is traditional for the audience to clap along (hopefully in tempo - the sure-fire indicator of whether the conductor is truly conducting and leading the orchestra, or merely beating time while the players themselves actually get on with it; only Herbert von Karajan in his singular outing at the New Year’s Concert of 1987 - one of the very best - is irrefutably the one fully calling the shots). If you’ve ever watched the broadcast it is hard not to imagine that half the bedecked and bejeweled audience is only there for this final Viennese knees-up: you can see them practically licking their lips as they adjust their pearls and neck ties in anticipation of the upbeat to their clap-a-along…

Karajan in charge at the 1987 New Year's Day Concert

Karajan in charge at the 1987 New Year's Day Concert

Yes, Karajan is the most disciplined - as indeed you would expect him to be, channeling his inner Prussian martinet. You can also discern his adoration of - and huge affinity for - classical’s lighter side… (beyond Strauss, check out his incomparable Offenbach, Lehar, and the delights of his operatic intermezzi, ballets, and other assorted bon-bons).

But it is Boskovsky on this particular set of records who most fully unleashes the side of the Viennese character that brought you all the indulgences of Strudel, Schlagsahne, and those fabulous coffees and chocolates, to be enjoyed while looking out over some of the most spectacular city vistas in Europe, and the Alpine pastures beyond (if not seen, then imagined).

Ah yes, to listen to Strauss is to imagine the Vienna of our dreams, before they briefly turned into the nightmares of the artist-manqué who foregrounded the city’s long tradition of antisemitism and made it a National cause. A key ingredient of his musical propaganda recipe was the music of Johann Strauss. Which means, alas, that while many will hear in the Radetzky March a harmless hommage to military foot-stomping and pomposity, others will still hear echoes of something more sinister. This piece in particular, originally composed to celebrate an Austrian army victory, does not fully escape the taint of its appropriation by the Nazis, who moved mountains to obscure the Strauss family’s Jewish origins.

However, it must be said that the inherent good humor and humanism of Strauss's music (as opposed to the emotional and ideological totalitarianism of Wagner) goes a long way towards banishing the taint of Nazism that attached itself for a while.

My original copy of this record is one I had dusted off a few years ago, and returned to occasionally, though in all honesty while enjoying the very “live” aspect of it all, I had tended to favour my old Decca OGs of Boskovsky and the gang recorded in the Sofiensaal when I needed a dose of Old Vienna.

Bringing out the original, digitally sourced pressing now for some critical listening, and dropping the needle on side one, my immediate thought as the orchestra launched into Strauss Senior’s delightful Echoes of the Lorelei was “How on earth did anyone, at any time (myself included), ever think think this was anything other than a sonic travesty?”

Were we all deaf? (And I include Decca’s engineers and producers of the time).

Back in 1979, had some malevolent sorcerer with world-conquering ambitions from the Vale of Digital Horrors somehow managed to cast so complete a spell that we all believed what we were hearing was an improvement on the analogue alternative already available to us?!!

I guess he had, because we all know what happened.

Granted that my stereo back in the day was nothing audiophile, but it was somewhat decent. How could I have missed the fact that this thing sonically sucked!

The strings have a metallic sheen, all glare and no soul. Every other instrument comes across almost as a cardboard cut-out of itself, present within an almost completely two-dimensional soundstage.

Yes, the percussion and the audience present themselves in an almost explosive manner, but it all becomes very fatiguing very quickly.

And yet this is all undoubtedly sonically superior to DG’s digital records of the same period, which makes it all the more miraculous when one considers the sonic upgrade given by the Emil Berliner team to the three digital recordings in the Karajan Bruckner cycle, released last year.

Well, fortunately, Decca here had some options beyond a digital “clean-up” and were able to source the untouched analogue back-up master for this reissue.

I managed to stick it out to the end of the first side of my copy of the original release, emerging from the digital desert like the ragged, emaciated figure of many a cartoon, panting for the relief of a tall glass of analogue!

Willi Boskovsky conducting the New Year's Day Concert (Photo: Decca)

Willi Boskovsky conducting the New Year's Day Concert (Photo: Decca)

The needle dropped on the reissue, and we were in another world. (Eagle-eared veterans of this record will notice that, unlike the original which opens with some audience applause, the reissue goes straight into the music; this must be because the analogue back-up was not rolling until after things had settled down in the Musikverein).

Strings were sounding not just like real strings, but VPO strings - a very particular breed with its own golden rich patina - with nary a trace of that digital glare and edge; winds sounded like winds, brass like brass… The percussion had lost none of its impact, but finally sounded like it was a part of the orchestra rather than an outside aggressor trying to mow it down. The soundstage is wide and full, but not enormous. In fact, if you look at photos of any orchestra concert at the Musikverein, you will see there is not a huge amount of room on the orchestra stage and behind it, so there is an appropriate sense of compactness to the aural space, which occasionally robs the double-basses (situated at the rear center of the stage, under the organ) of their full resonance.

It remains a lively recording, with the audience very present. This is very different from today’s live recordings which tend to try and “extract” the audience as much as possible. No, this is clearly an “event” record, and all the better for it. You will especially enjoy the audience interactions during the last side of the record - they add such a degree of fun to these old classical chestnuts, being heard as they were intended to be heard, in a “live” situation with the audience free to express their joy at this life-affirming music - and jump at those gunshots!

The closely-miked nature of the recording (alluded to in Dominic Fyfe’s accompanying essay) is part of the reason for the immediacy of the sound - and the stridency of the original digital release. But for this reissue Rainer Maillard has once again called upon the stairwell at Emil Berliner Studios to work its magic to provide us with a most pleasing simulacrum of the Musikverein’s hall ambience and reverberation. No, this is not a recording made with two channels of dedicated ambient sound as with the Deutsche Grammophon Original Source reissues, but I feel that this restoration (for restoration it is) has really benefited from all the lessons learned so far by the Emil Berliner team as they have striven to find the perfect balance between the direct sound, ambient sound, and staircase reverb they have been blending together for those Original Source releases. The integration between the Vienna Philharmonic, the Musikverein and the audience sitting in it is seamless and very organic sounding, and by a wide margin superior to the electronically induced version of same on the CD reissue of this album in the Decca Classic Sound series. Let us also not fail to mention the incredibly clean and dynamic cut by Sidney C. Meyer, as always the increasingly not-so-secret weapon in Emil Berliner Studios’ arsenal.

Now free to sink into the sonics of this legendary recording rather than grit my teeth in order to just get through it, I found myself reveling in this life-affirming music. And for anyone interested in hearing the echt-Viennese style in this music (and if you’re not interested, you should be), the VPO is the place to turn. You will notice two things immediately that are harder to come by on recordings of the Strauss family by other ensembles.

Firstly, there is a very specific unevenness in the way the three-beats-to-a-bar waltz rhythm is played, resulting in a wonderfully sprung pulse that literally makes the music dance. I defy you not to start air-conducting at the very least, let alone grabbing a partner (real or imagined) to dance around your listening room.. I am not even sure this special way with the waltz rhythm is something a conductor alone can convey (for one thing the waltzes tend to be conducted with a one-in-a-bar beat); it simply has to be in the bones of the musicians themselves.

Secondly, you will hear a far greater use of rubato - a slowing and speeding up within the musical phrase - in the Viennese performances, done in such a way as to not break up the musical line. Other orchestras who attempt this can come a cropper. In addition the distinct sonorities of the VPO, with its golden rich string tone; rounder, more mellow winds; and deeply burnished brass, timbres that all blend together seamlessly, together lend the music a very specific sonority. All these characteristics of the VPO tend to make this particular orchestra’s version of Strauss & co. sound like the most authentic one, speaking in a direct line from the composer himself.

Johann Strauss II conducting one of his six orchestras, by Theo Zasche

Johann Strauss II conducting one of his six orchestras, by Theo Zasche

As with all New Year’s Day Concerts, the repertoire is a healthy mix of the almost unknown and the overly-familiar. The output of the Strauss family was enormous, so it seems like with every New Year's Day Concert there are new discoveries to be made. Conductors have often cast their nets beyond the Strauss dynasty to include other composers working in a lighter vein like Franz Lehar, Emil Waldteufel, Otto Nicolai, Franz von Suppè, and even Beethoven and Bruckner letting their hair down!

However, Willi Boskovsky was Old School, so his program is a purist one, with only two non-Strauss family works, by Carl Michael Ziehrer - a frequent guest on New Year's programs - and Franz von Suppé (his Overture to The Beautiful Galatea, a highlight of the concert). When this recording was released, it was the first time that the New Year’s Concert was presented complete on record, and thus it was the first time that listeners could enjoy more of the rarer corners of the Strauss family enterprise. There are some real gems to be enjoyed here on route to the big hits of the final side.

I will mention some personal highlights.

With the Brakes Off Polka - the first example of the “letting-the orchestra-off-the-leash” category of pieces that pepper the concert. Too. Much. Fun!

Wine, Women and Song - one of the Strauss evergreens, again so idiomatically done.

Franz von Suppé

Franz von Suppé

Suppé’s Overture to The Beautiful Galatea. After the rambunctuous opening (required to drown out and settle down the impending show’s rowdy audience), this settles into a portrait of the beautiful Lady in Question being sculpted by Pygmalion. Against shimmering strings the flute and wind weave and seduce, then evolve with accompanying plucked strings that sound so natural and resonant, and it is all quite irresistible. As was the lady to be to her creator…

The triptych of polkas that open Side 3 let the novelty percussion shine and the orchestra show off their chops. The tinkling glockenspiel does sterling service in particular, and lovers of Strauss’s Die Fledermaus disappointed not to see the Overture to that operetta on the program will be compensated by the parade of Fledermaus hits in the Tik-Tak Polka. There follows one of my perennial favorites, the Pizzicato Polka. I seriously go for anything with lots of pizzicato: quite happy to forego all of Tchaikovsky’s 4th Symphony in favor of the pizzicato-led third movement, or put on repeat the Playful Pizzicato movement of Britten’s Simple Symphony. The VPO and Boskovsky do not disappoint. The final big chord resonates beautifully in the hall.

Side 3 is altogether a hit parade, ending with a lovely, lovely rendering of Josef Strauss’s ethereal Music of the Spheres Waltz. It sounds just the way you would expect it to - heavenly.

The Strauss Boys: (from l. to r.) Eduard, Johann II and Josef

The Strauss Boys: (from l. to r.) Eduard, Johann II and Josef

And then Side 4 kicks off with the At the Hunt Polka, complete with the drums mimicking gunshots, and then as close to the real thing as you’re going to get in a concert hall. The audience goes wild! On the reprise, the final gun shots somehow add a whole extra level of bass and power, and the effect is galvanizing. We are all reduced to gleeful delighted-in-our-terror kids.

After tossing off another Strauss perennial, the Light of Heart Polka, we get the traditional New Year’s greeting from the conductor, sounding suitably full of Austrian bonhomie.

As alluded to earlier, the final one-two punch of the Blue Danube and the Radetzky March is delivered flawlessly - and indelibly; these remain my favorites of any versions of these works I have heard, in part because of the lively response and involvement of the audience. Blue Danube is performed with all the sense of awe, beauty and grace the work demands, and with no needless mucking around with the tempo and rubato - direct and to the point, letting the music speak for itself; you will simply glow by the end. Then everyone gets down for a bit of Radetzky rowdiness that almost gets out of hand a few times. (Karajan would not be amused). How can any year go badly when it starts off with this much positive energy and sheer fun? Perfect.

The traditional end of the New Year's Day Concert (the conductor here is Zubin Mehta)

The traditional end of the New Year's Day Concert (the conductor here is Zubin Mehta)

This was to be Boskovsky’s final outing at the helm of the New Year’s Day Concert. Ill-health forced his retirement later in 1979, and in 1980 Lorin Maazel began the tradition that persists to today of inviting star conductors to strut their Straussian stuff (Maazel, like Boskovsky, was a violinist, so he was able to play along with the band too when he felt like it).

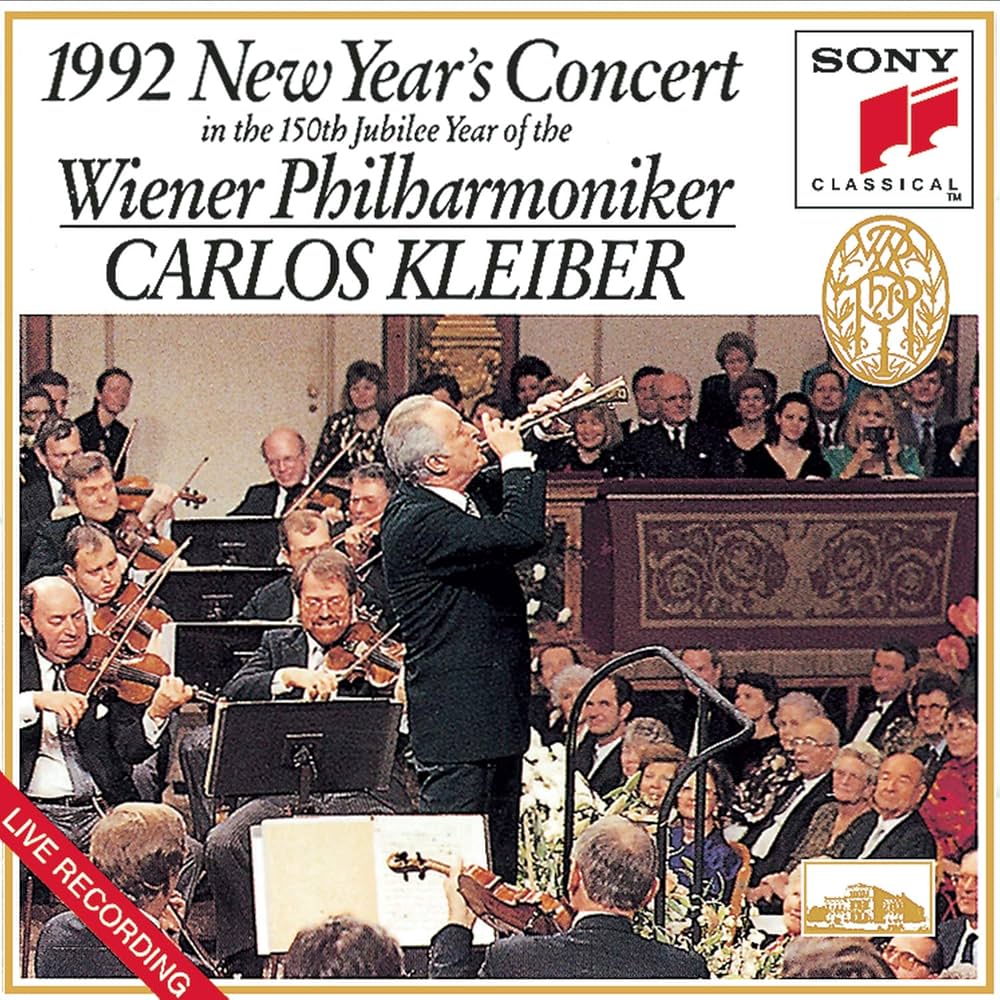

For me, this 1979 Concert - especially now in its sonically rejuvenated form - remains the one essential recording of the event I would want to have in my library, but I will add that Karajan’s 1987 outing runs it a close second, along with Carlos Kleiber’s two stints in 1987 and 1992.

A few words on presentation and packaging. Clearly the Decca team is drawing on the experience and example of the DG Original Source Series. The presentation of two 180-gram platters is within a facsimile of the original gatefold, with all original artwork and documentation (a detailed breakdown of each piece in English, French and German) present. The board stock for the jackets is a mite thicker than for the Original Source reissues, and all the better for it. As far as I can tell, all the Decca Pure Analogue releases will be presented in gatefolds, whether or not the original releases were single or double LP sets.

As I alluded to above, a really nice feature is the inclusion with each of these Decca Pure Analogue releases of a new article written by Decca Classics Label Director, Dominic Fyfe, filling in pertinent historical, musical and technical detail. (This is something that I hope DG may emulate as it moves forwards, something akin to the essays it used to include in its Originals CD reissues). This essay is included on a separate heavy duty insert, presented with some classy gold embossing around the edges, above the signatures of Fyfe, Rainer Maillard and Sidney C. Meyer - an appropriate nod to the technical wizards making all this sonic goodness possible. The reverse features two new photos of the concert, orchestra and conductor (both used within this article above).

As with the Original Source, the jackets are presented in a matte finish which becomes a glossy one once the transparent outer sleeve is placed around the LP - a nod to the archive nature of the releases which I have always liked. This outer sleeve is again heavier duty than the ones provided for the Original Source, and I think it is an improvement, far less likely to fray and split as one removes and inserts the records. DG should consider upgrading.

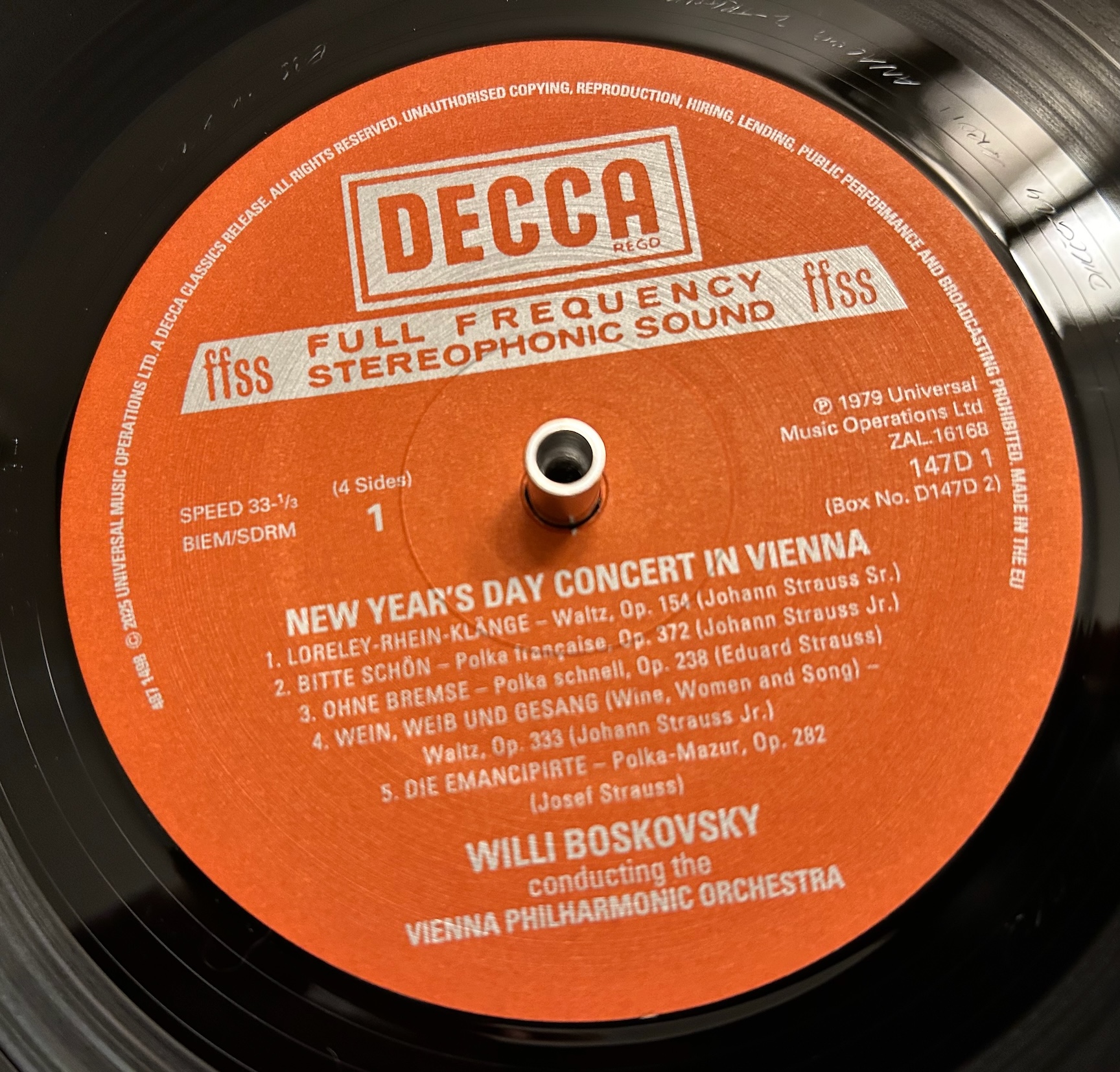

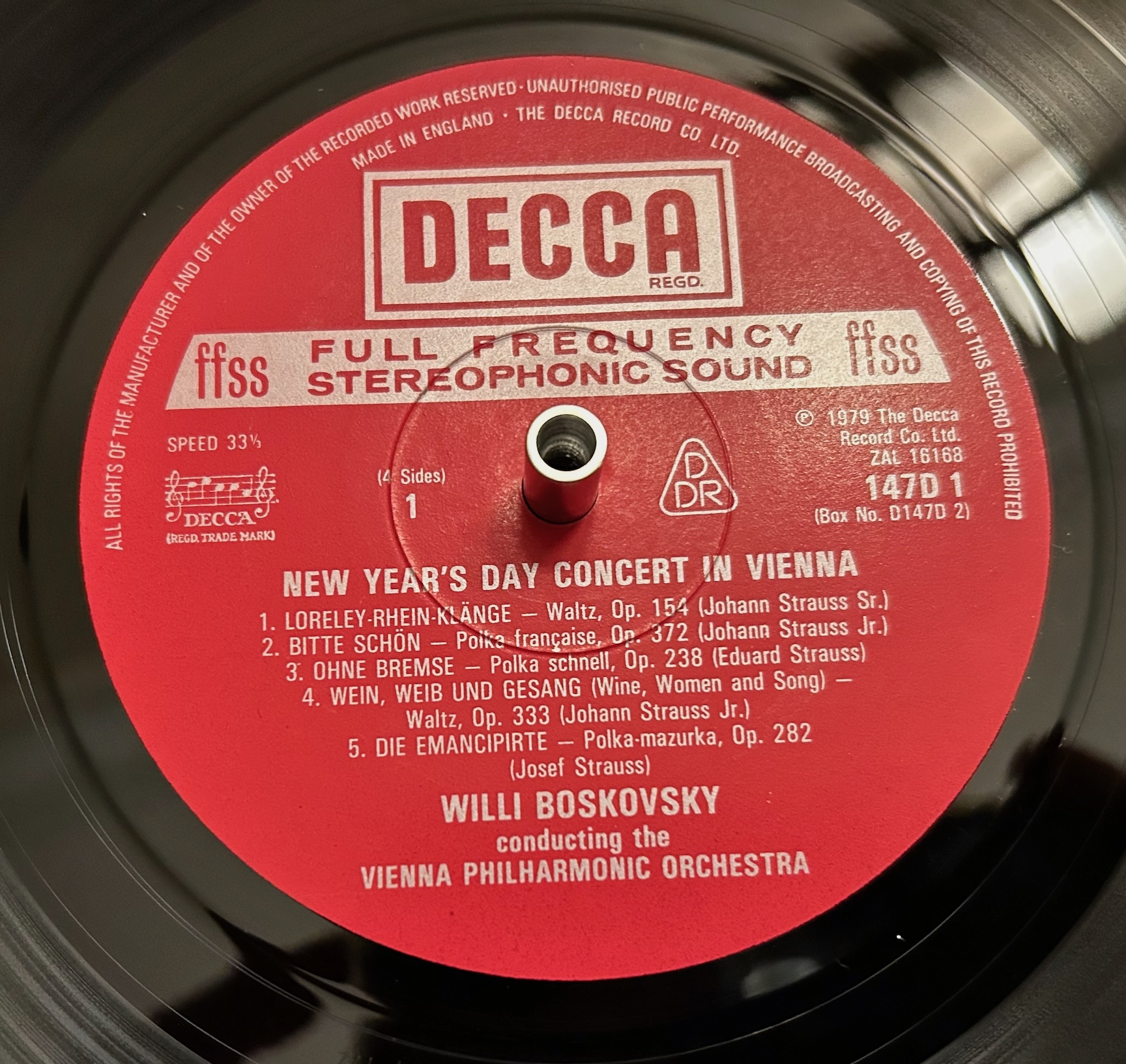

This does, however, bring me to the one design element I am not so sure about, and that is the decision - in keeping with the notion of giving the whole package its own distinct “archive” identity - to create a variation on the original record labels. Essentially, what Decca has done is to produce a matted variant of the original center label, and in a slightly different shade of the original label color.

Back in the day, Decca would maintain a similar graphic design for its center-of-record labels for certain periods of production, but would vary the color depending on the genre of the music. Most stereo classical Decca center labels were black or purple, but in the 1970s they started to introduce other colors such as the bright glossy red of the original 1979 New Year’s Day Concert. For this reissue the color is closer to a somewhat lackluster burnt orange, made even more muted by being in a matte finish.

At the risk of entering serious vinyl nerd territory, I am pretty sure I do not like this - the original red really popped, and the semi-glossy finish added a hint of luxury as you both looked at and handled the record. Not so much now.

For its Original Source reissues, DG has not messed with its original record labels, and I wish Decca had emulated their example.

I am sure there were discussions about all this, and others may disagree with me, but I think Decca should reconsider and go back to the design and color/finish of those original record labels. (There’s something similar done with the labels on the other two Decca Pure Analogue releases, and I don’t like them either). Many will consider I am being ridiculously nit-picky on this point, but it’s bugging me. And I will mention that the first thing our editor Michael Fremer said to me upon receiving his copies was a none-too-positive remark about the redesign of these center labels.

[ADDENDUM: I received feedback from Decca/DG that apparently the paper stock on which these record labels is printed is unique to Pallas and cannot be altered. Obviously my somewhat pedantic preference still stands, but there's nothing to be done about it. This is hardly the end of the world, and to be honest as I have handled and played all these records it has bothered me less.]

Back to something more important - the pressing quality. Unlike the Original Source releases, which are pressed at Optimal, these have been pressed at Pallas, and my copies were perfect. EXCEPT - some clearly visible marks on the lead-in and early grooves of my favorite Side 4 of the set. Not good, and something of a mystery since MF informed me that at the Pallas plant there is no manual handling of platters en route to their inner sleeves (polylined, thank goodness) - it’s all done mechanically with no humans involved (at least that's how it was done on the Toolex Alpha machines in use when I visited_ed.). After a thorough cleaning it looked like some of the marks had dissipated, but some remained. I was somewhat anxious about how many audible scratches I might hear both in the silence before the track began, and in the first few rotations of the record. However, a huge sigh of relief escaped my lips as nothing sounded at all - something that really can happen even when you see visible defects on the vinyl (and vice versa). Might not have been the case if I hadn’t given the record a thorough cleaning before playing: a reminder that everyone should be properly cleaning even brand new records. (I will note that MF had no problems with his copy of this title).

As per usual, I “ummed and aahed” concerning my final ratings for Music and Sound. This just misses the prized “10” in both categories simply because, while this is terrific music given iconic performances, is it really tippety-top-top of the class in both respects? Am I really going to place Strauss on the same level as Mozart, Beethoven, Brahms et al in an absolute sense? (Make no mistake - this is the Waltz King and his family members played as idiomatically as it’s possible to play them). Likewise the sound is indeed superb, casting the original into the abyss where all early digital goes to die, but can I hand-on-heart say it is the best of the best? Not quite. However, I will say that in its sense of immediacy, of being right there at the concert in its occasionally untidy, roustabout way, this recording is preferable to most of today’s live gigs that have substituted for new studio recordings in the classical lists, digitally scrubbed clean of every conceivable artifact that might otherwise breathe some life into perfectly manicured but soulless soundscapes.

Besides, if I had been doing the written reviews for the next two titles in this batch of reissues, I might have needed to access that extra point on both Sound and Music scales by way of comparison to this release (hint, hint… Over to you Paul and Michael…)

But no-one remotely interested in this music - and this series - need hesitate. For my money it’s the most iconic - and essential - representation of the live New Year’s Day Concert from Vienna on recorded media.

IN CONCLUSION…

This is an auspicious start to the Decca Pure Analogue series, not least for bringing us a truly historic moment in recorded history in vastly improved sonics. If the series continues in this vein, every release day is going to be like falling into an Aladdin’s Cave of musical and sonic delights.

Consider the vast riches not just of the main Decca and Philips catalogues available for this purist AAA refurbishment. You’ve got the early music wonders of the L’Oiseau-Lyre catalogue, including Christopher Hogwood’s unmatched Messiah; the endless riches of the Argo catalogue, including all those exquisite choral records from King’s College and St. John’s College, Cambridge, plus the Academy of St. Martin-in-the-Fields records, including their peerless set of Michael Tippett’s masterpieces for strings, as luscious a recording as any in my collection, of music that is barely known, but once known is rarely anything other than adored; you’ve got the miraculous Mercury Living Presence catalogue (Dorati’s benchmark Nutcracker for starters, in a non-limited edition please so it can sell tons every Christmas); you’ve got so many early digital records that may have useable analogue back-up masters - encompassing Dutoit in Montreal, Dorati’s Indian Summer, some of the great early Christoph von Dohnányi records in Vienna; the extraordinary contemporary works featured on Headline and beyond; the untold riches of the many benchmark opera recordings; Colin Davis’s Berlioz, and Ozawa’s Gurrelieder on Philips; Solti, Solti, Solti… (how about his Haydn symphonies if there are analogue back-ups; and that Mahler 8th for sure - and I don’t even really like the piece, but this I’d buy in a heartbeat). I could go on and on…

So a very enthusiastic welcome indeed to this debut release of the Decca Pure Analogue Series. My colleagues Paul Seydor and Michael Johnson will be covering the other two titles in this first batch - Colin Davis’s Sibelius 5th and 7th Symphonies, and Solti’s Rite of Spring respectively. I will merely say that from what I’ve listened to so far there is no need to delay on acquiring copies of either or both if the music and performances appeal. They are limited editions, so they will sell out (although I imagine the more popular titles may get an unnumbered repress down the road, if the example of DG is anything to go by).

What a great time it is to be a classical enthusiast who loves records! Keep ‘em coming and we’ll keep buying…

Now - Warner (EMI) and Sony (Columbia/RCA) - how about you dip your toes in the AAA vinyl waters…

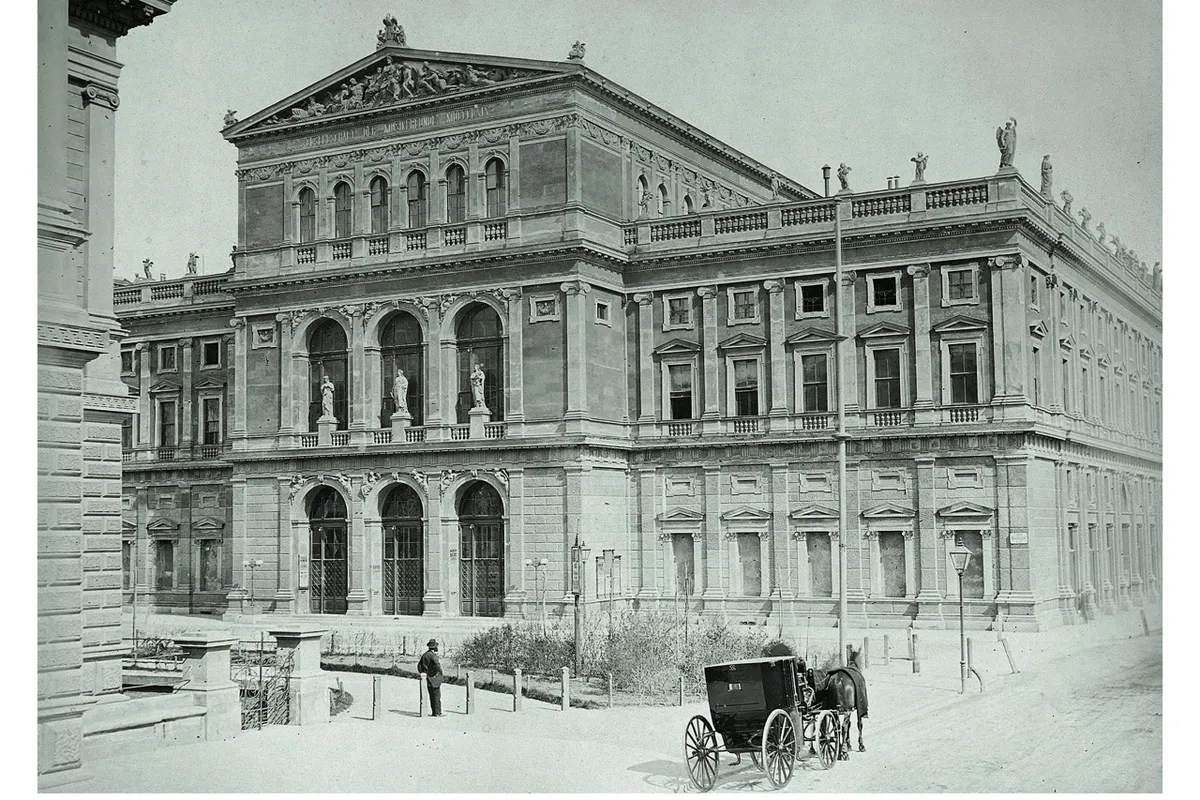

The Musikverein in 1870

The Musikverein in 1870

Limited edition of 3220 hand-numbered copies. You can purchase the Decca Pure Analogue release of the 1979 New Year's Day Concert here.

Watch the video discussion on the new Decca Pure Analogue series here.

.png)